Sanskrit

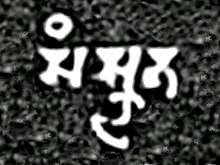

Sanskrit (/ˈsænskrɪt/;[7] Sanskrit: संस्कृतम्, romanized: saṃskṛtam, IPA: [ˈsɐ̃skr̩tɐm] (![]()

| Sanskrit | |

|---|---|

| संस्कृतम् Saṃskṛtam | |

_in_Sanskrit.svg.png) Saṃskṛtam in Devanagari script | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈsɐ̃skr̩tɐm] ( |

| Region | South Asia Parts of Southeast Asia |

| Era | c. 2nd millennium BCE – 600 BCE (Vedic Sanskrit);[1] 600 BCE – present (Classical Sanskrit) |

| Revival | 24,821 people in India[2] and 1,669 people in Nepal[3] have registered Sanskrit as their mother tongue. There are 2,360,821 total speakers of Sanskrit in India.[4] |

Indo-European

| |

Early form | |

| Most commonly in Devanagari, also written in various other Brahmic scripts[5] | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | sa |

| ISO 639-2 | san |

| ISO 639-3 | san |

| Glottolog | sans1269[6] |

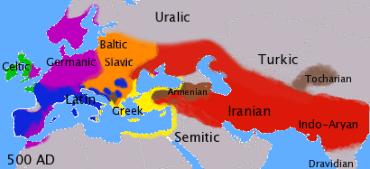

Sanskrit is an Old Indo-Aryan language.[9] As one of the oldest documented members of the Indo-European family of languages,[20][note 1][note 2] Sanskrit holds a prominent position in Indo-European studies.[23] It is related to Greek and Latin,[9] as well as Hittite, Luwian, Old Avestan and many other living and extinct languages with historical significance to Europe, West Asia, Central Asia and South Asia. It traces its linguistic ancestry to the Proto-Indo-Aryan, Proto-Indo-Iranian and Proto-Indo-European languages.[24]

Sanskrit is traceable to the 2nd millennium BCE in a form known as Vedic Sanskrit,[25] with the Rigveda as the earliest-known composition. A more refined and standardized grammatical form called Classical Sanskrit emerged in the mid-1st millennium BCE with the Aṣṭādhyāyī treatise of Pāṇini.[9] The broader definition of Sanskrit refers to the whole range of mutually intelligible Old Indo-Aryan dialects spoken in North-western India at the time of the composition of the Vedas and thus can be treated as the ancestor of the Prakrits and Pali, and consequently, of all Modern Indo-Aryan languages like Hindi, Marathi, Bengali, Punjabi, Gujarati, Sindhi, Kashmiri, Kumaoni, Garhwali, Urdu, Dogri, Maithili, Konkani, Assamese, Odia, and Nepali.[26][27][28] On the other hand, the standardized Classical and Epic Sanskrit was a literary language and not the ancestor of any Indo-Aryan language.[29] Sanskrit has significantly influenced the grammar, phonology and vocabulary of the Kannada, Telugu, Tamil and Malayalam languages of South India.[30][31][32]

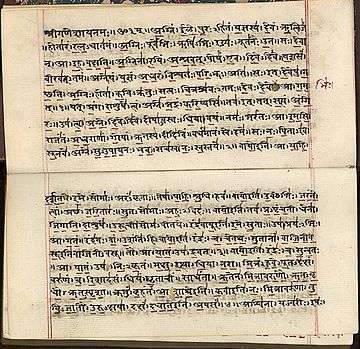

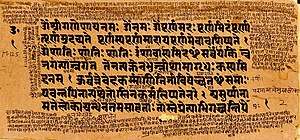

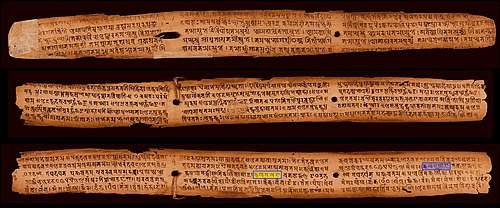

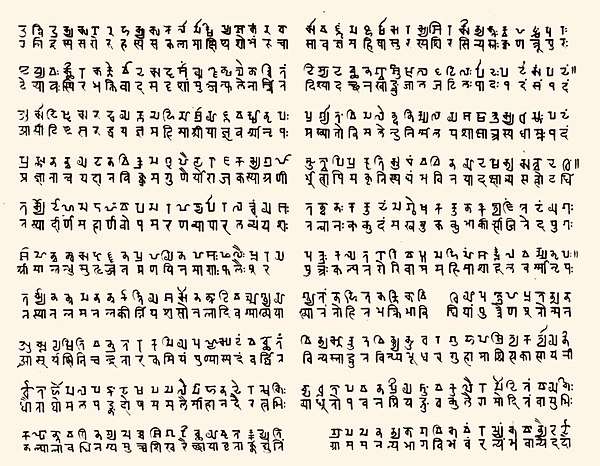

The body of Sanskrit literature encompasses a rich tradition of philosophical and religious texts, as well as poetry, music, drama, scientific, technical and other texts. In the ancient era, Sanskrit compositions were orally transmitted by methods of memorisation of exceptional complexity, rigour and fidelity.[33][34] The earliest known inscriptions in Sanskrit are from the 1st century BCE, such as the few discovered in Ayodhya and Ghosundi-Hathibada (Chittorgarh).[35][note 3] Sanskrit texts dated to the 1st millennium CE were written in the Brahmi script, the Nāgarī script, the historic South Indian scripts and their derivative scripts.[39][40][41] Sanskrit is one of the 22 languages listed in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution of India. More than 3,000 Sanskrit works have been composed since India's independence in 1947.[42] Sanskrit is a living language and spoken as a primary language in some villages in India. It is taught in a large number of schools in India. It also continues to be widely used as a ceremonial and ritual language in Hinduism and some Buddhist practices such as recitation of hymns and chants.

Etymology and nomenclature

In Sanskrit verbal adjective sáṃskṛta- is a compound word consisting of sam (together, good, well, perfected) and krta- (made, formed, work).[43][44] It connotes a work that has been "well prepared, pure and perfect, polished, sacred".[45][46][47] According to Biderman, the perfection contextually being referred to in the etymological origins of the word is its tonal—rather than semantic—qualities. Sound and oral transmission were highly valued qualities in ancient India, and its sages refined the alphabet, the structure of words and its exacting grammar into a "collection of sounds, a kind of sublime musical mold", states Biderman, as an integral language they called Sanskrit.[44] From the late Vedic period onwards, state Annette Wilke and Oliver Moebus, resonating sound and its musical foundations attracted an "exceptionally large amount of linguistic, philosophical and religious literature" in India. Sound was visualized as "pervading all creation", another representation of the world itself; the "mysterious magnum" of Hindu thought. The search for perfection in thought and the goal of liberation were among the dimensions of sacred sound, and the common thread that weaved all ideas and inspirations became the quest for what the ancient Indians believed to be a perfect language, the "phonocentric episteme" of Sanskrit.[48][49]

Sanskrit as a language competed with numerous, less exact vernacular Indian languages called Prakritic languages (prākṛta-). The term prakrta literally means "original, natural, normal, artless", states Franklin Southworth.[50] The relationship between Prakrit and Sanskrit is found in Indian texts dated to the 1st millennium CE. Patañjali acknowledged that Prakrit is the first language, one instinctively adopted by every child with all its imperfections and later leads to the problems of interpretation and misunderstanding. The purifying structure of the Sanskrit language removes these imperfections. The early Sanskrit grammarian Daṇḍin states, for example, that much in the Prakrit languages is etymologically rooted in Sanskrit, but involve "loss of sounds" and corruptions that result from a "disregard of the grammar". Daṇḍin acknowledged that there are words and confusing structures in Prakrit that thrive independent of Sanskrit. This view is found in the writing of Bharata Muni, the author of the ancient Nāṭyaśāstra text. The early Jain scholar Namisādhu acknowledged the difference, but disagreed that the Prakrit language was a corruption of Sanskrit. Namisādhu stated that the Prakrit language was the pūrvam (came before, origin) and that it came naturally to children, while Sanskrit was a refinement of Prakrit through "purification by grammar".[51]

History

Origin and development

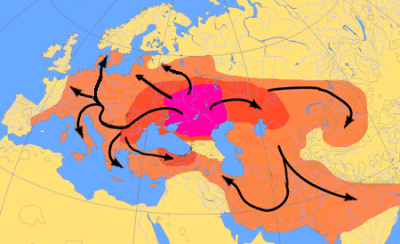

Sanskrit belongs to the Indo-European family of languages. It is one of three ancient documented languages that arose from a common root language now referred to as Proto-Indo-European language:[21][52][53]

- Vedic Sanskrit (c. 1500 – 500 BCE).

- Mycenaean Greek (c. 1450 BCE)[54] and Ancient Greek (c. 750 – 400 BC).

- Hittite (c. 1750 – 1200 BCE).

Other Indo-European languages related to Sanskrit include archaic and classical Latin (c. 600 BCE – 100 CE, old Italian), Gothic (archaic Germanic language, c. 350 CE), Old Norse (c. 200 CE and after), Old Avestan (c. late 2nd millennium BCE[55]) and Younger Avestan (c. 900 BCE).[52][53] The closest ancient relatives of Vedic Sanskrit in the Indo-European languages are the Nuristani languages found in the remote Hindu Kush region of the northeastern Afghanistan and northwestern Himalayas,[53][56][57] as well as the extinct Avestan and Old Persian—both Iranian languages.[58][59][60] Sanskrit belongs to the satem group of the Indo-European languages.

Colonial era scholars familiar with Latin and Greek were struck by the resemblance of the Sanskrit language, both in its vocabulary and grammar, to the classical languages of Europe.[note 4] It suggested a common root and historical links between some of the major distant ancient languages of the world.[note 5]

In order to explain the common features shared by Sanskrit and other Indo-European languages, the Indo-Aryan migration theory states that the original speakers of what became Sanskrit arrived in the Indian subcontinent from the north-west sometime during the early second millennium BCE. Evidence for such a theory includes the close relationship between the Indo-Iranian tongues and the Baltic and Slavic languages, vocabulary exchange with the non-Indo-European Uralic languages, and the nature of the attested Indo-European words for flora and fauna.[63] The pre-history of Indo-Aryan languages which preceded Vedic Sanskrit is unclear and various hypotheses place it over a fairly wide limit. According to Thomas Burrow, based on the relationship between various Indo-European languages, the origin of all these languages may possibly be in what is now Central or Eastern Europe, while the Indo-Iranian group possibly arose in Central Russia.[64] The Iranian and Indo-Aryan branches separated quite early. It is the Indo-Aryan branch that moved into eastern Iran and then south into the Indian subcontinent in the first half of the 2nd millennium BCE. Once in ancient India, the Indo-Aryan language underwent rapid linguistic change and morphed into the Vedic Sanskrit language.[65]

Vedic Sanskrit

The pre-Classical form of Sanskrit is known as Vedic Sanskrit. The earliest attested Sanskrit text is the Rigveda, a Hindu scripture, from the mid-to-late second millennium BCE. No written records from such an early period survive if they ever existed. However, scholars are confident that the oral transmission of the texts is reliable: they were ceremonial literature where the exact phonetic expression and its preservation were a part of the historic tradition.[66][67][68]

The Rigveda is a collection of books, created by multiple authors from distant parts of ancient India. These authors represented different generations, and the mandalas 2 to 7 are the oldest while the mandalas 1 and 10 are relatively the youngest.[69][70] Yet, the Vedic Sanskrit in these books of the Rigveda "hardly presents any dialectical diversity", states Louis Renou—an Indologist known for his scholarship of the Sanskrit literature and the Rigveda in particular. According to Renou, this implies that the Vedic Sanskrit language had a "set linguistic pattern" by the second half of the 2nd millennium BCE.[71] Beyond the Rigveda, the ancient literature in Vedic Sanskrit that has survived into the modern age include the Samaveda, Yajurveda, Atharvaveda along with the embedded and layered Vedic texts such as the Brahmanas, Aranyakas and the early Upanishads.[66] These Vedic documents reflect the dialects of Sanskrit found in the various parts of the northwestern, northern and eastern Indian subcontinent.[9][72]

Vedic Sanskrit was both a spoken and literary language of ancient India. According to Michael Witzel, Vedic Sanskrit was a spoken language of the semi-nomadic Aryas who temporarily settled in one place, maintained cattle herds, practiced limited agriculture and after some time moved by wagon trains they called grama.[73][74] The Vedic Sanskrit language or a closely related Indo-European variant was recognized beyond ancient India as evidenced by the "Mitanni Treaty" between the ancient Hittite and Mitanni people, carved into a rock, in a region that are now parts of Syria and Turkey.[75][note 6] Parts of this treaty such as the names of the Mitanni princes and technical terms related to horse training, for reasons not understood, are in early forms of Vedic Sanskrit. The treaty also invokes the gods Varuna, Mitra, Indra and Nasatya found in the earliest layers of the Vedic literature.[75][77]

O Brihaspati, when in giving names

they first set forth the beginning of Language,

Their most excellent and spotless secret

was laid bare through love,

When the wise ones formed Language with their mind,

purifying it like grain with a winnowing fan,

Then friends knew friendships –

an auspicious mark placed on their language.

The Vedic Sanskrit found in the Rigveda is distinctly more archaic than other Vedic texts, and in many respects, the Rigvedic language is notably more similar to those found in the archaic texts of Old Avestan Zoroastrian Gathas and Homer's Iliad and Odyssey.[79] According to Stephanie W. Jamison and Joel P. Brereton—Indologists known for their translation of the Rigveda—the Vedic Sanskrit literature "clearly inherited" from Indo-Iranian and Indo-European times the social structures such as the role of the poet and the priests, the patronage economy, the phrasal equations, and some of the poetic meters.[80][note 7] While there are similarities, state Jamison and Brereton, there are also differences between Vedic Sanskrit, the Old Avestan, and the Mycenaean Greek literature. For example, unlike the Sanskrit similes in the Rigveda, the Old Avestan Gathas lack simile entirely, and it is rare in the later version of the language. The Homerian Greek, like Rigvedic Sanskrit, deploys simile extensively, but they are structurally very different.[82]

Classical Sanskrit

The early Vedic form of the Sanskrit language was far less homogenous, and it evolved over time into a more structured and homogeneous language, ultimately into the Classical Sanskrit by about the mid-1st millennium BCE. According to Richard Gombrich—an Indologist and a scholar of Sanskrit, Pāli and Buddhist Studies—the archaic Vedic Sanskrit found in the Rigveda had already evolved in the Vedic period, as evidenced in the later Vedic literature. The language in the early Upanishads of Hinduism and the late Vedic literature approaches Classical Sanskrit, while the archaic Vedic Sanskrit had by the Buddha's time become unintelligible to all except ancient Indian sages, states Gombrich.[83]

The formalization of the Sanskrit language is credited to Pāṇini, along with Patanjali's Mahabhasya and Katyayana's commentary that preceded Patanjali's work.[84] Panini composed Aṣṭādhyāyī ("Eight-Chapter Grammar"). The century in which he lived is unclear and debated, but his work is generally accepted to be from sometime between 6th and 4th centuries BCE.[85][86][87]

The Aṣṭādhyāyī was not the first description of Sanskrit grammar, but it is the earliest that has survived in full. Pāṇini cites ten scholars on the phonological and grammatical aspects of the Sanskrit language before him, as well as the variants in the usage of Sanskrit in different regions of India.[88] The ten Vedic scholars he quotes are Apisali, Kashyapa, Gargya, Galava, Cakravarmana, Bharadvaja, Sakatayana, Sakalya, Senaka and Sphotayana.[89] The Aṣṭādhyāyī of Panini became the foundation of Vyākaraṇa, a Vedanga.[90] In the Aṣṭādhyāyī, language is observed in a manner that has no parallel among Greek or Latin grammarians. Pāṇini's grammar, according to Renou and Filliozat, defines the linguistic expression and a classic that set the standard for the Sanskrit language.[91] Pāṇini made use of a technical metalanguage consisting of a syntax, morphology and lexicon. This metalanguage is organised according to a series of meta-rules, some of which are explicitly stated while others can be deduced.[92]

Pāṇini's comprehensive and scientific theory of grammar is conventionally taken to mark the start of Classical Sanskrit.[93] His systematic treatise inspired and made Sanskrit the preeminent Indian language of learning and literature for two millennia.[94] It is unclear whether Pāṇini wrote his treatise on Sanskrit language or he orally created the detailed and sophisticated treatise then transmitted it through his students. Modern scholarship generally accepts that he knew of a form of writing, based on references to words such as lipi ("script") and lipikara ("scribe") in section 3.2 of the Aṣṭādhyāyī.[95][96][97][note 8]

The Classical Sanskrit language formalized by Pāṇini, states Renou, is "not an impoverished language", rather it is "a controlled and a restrained language from which archaisms and unnecessary formal alternatives were excluded".[104] The Classical form of the language simplified the sandhi rules but retained various aspects of the Vedic language, while adding rigor and flexibilities, so that it had sufficient means to express thoughts as well as being "capable of responding to the future increasing demands of an infinitely diversified literature", according to Renou. Pāṇini included numerous "optional rules" beyond the Vedic Sanskrit's bahulam framework, to respect liberty and creativity so that individual writers separated by geography or time would have the choice to express facts and their views in their own way, where tradition followed competitive forms of the Sanskrit language.[105]

The phonetic differences between Vedic Sanskrit and Classical Sanskrit are negligible when compared to the intense change that must have occurred in the pre-Vedic period between Indo-Aryan language and the Vedic Sanskrit.[106] The noticeable differences between the Vedic and the Classical Sanskrit include the much-expanded grammar and grammatical categories as well as the differences in the accent, the semantics and the syntax.[107] There are also some differences between how some of the nouns and verbs end, as well as the sandhi rules, both internal and external.[107] Quite many words found in the early Vedic Sanskrit language are never found in late Vedic Sanskrit or Classical Sanskrit literature, while some words have different and new meanings in Classical Sanskrit when contextually compared to the early Vedic Sanskrit literature.[107]

Arthur Macdonell was among the early colonial era scholars who summarized some of the differences between the Vedic and Classical Sanskrit.[107][108] Louis Renou published in 1956, in French, a more extensive discussion of the similarities, the differences and the evolution of the Vedic Sanskrit within the Vedic period and then to the Classical Sanskrit along with his views on the history. This work has been translated by Jagbans Balbir.[109]

Sanskrit and Prakrit languages

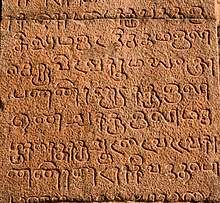

Mandsaur stone inscription of Yashodharman-Vishnuvardhana, 532 CE.[110]

The earliest known use of the word Saṃskṛta (Sanskrit), in the context of a language, is found in verses 3.16.14 and 5.28.17–19 of the Ramayana.[111][note 9]. Outside the learned sphere of written Classical Sanskrit, vernacular colloquial dialects (Prakrits) continued to evolve. Sanskrit co-existed with numerous other Prakrit languages of ancient India. The Prakrit languages of India also have ancient roots and some Sanskrit scholars have called these Apabhramsa, literally "spoiled".[113][114] The Vedic literature includes words whose phonetic equivalent are not found in other Indo-European languages but which are found in the regional Prakrit languages, which makes it likely that the interaction, the sharing of words and ideas began early in the Indian history. As the Indian thought diversified and challenged earlier beliefs of Hinduism, particularly in the form of Buddhism and Jainism, the Prakrit languages such as Pali in Theravada Buddhism and Ardhamagadhi in Jainism competed with Sanskrit in the ancient times.[115][116][117] However, states Paul Dundas, a scholar of Jainism, these ancient Prakrit languages had "roughly the same relationship to Sanskrit as medieval Italian does to Latin."[117] The Indian tradition states that the Buddha and the Mahavira preferred the Prakrit language so that everyone could understand it. However, scholars such as Dundas have questioned this hypothesis. They state that there is no evidence for this and whatever evidence is available suggests that by the start of the common era, hardly anybody other than learned monks had the capacity to understand the old Prakrit languages such as Ardhamagadhi.[117][note 10]

Colonial era scholars questioned whether Sanskrit was ever a spoken language, or just a literary language.[119] Scholars disagree in their answers. A section of Western scholars state that Sanskrit was never a spoken language, while others and particularly most Indian scholars state the opposite.[120] Those who affirm Sanskrit to have been a vernacular language point to the necessity of Sanskrit being a spoken language for the oral tradition that preserved the vast number of Sanskrit manuscripts from ancient India. Secondly, they state that the textual evidence in the works of Yaksa, Panini and Patanajali affirms that the Classical Sanskrit in their era was a language that is spoken (bhasha) by the cultured and educated. Some sutras expound upon the variant forms of spoken Sanskrit versus written Sanskrit.[120] The 7th-century Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Xuanzang mentioned in his memoir that official philosophical debates in India were held in Sanskrit, not in the vernacular language of that region.[120]

According to Sanskrit linguist Madhav Deshpande, Sanskrit was a spoken language in a colloquial form by the mid-1st millennium BCE which coexisted with a more formal, grammatically correct form of literary Sanskrit.[13] This, states Deshpande, is true for modern languages where colloquial incorrect approximations and dialects of a language are spoken and understood, along with more "refined, sophisticated and grammatically accurate" forms of the same language being found in the literary works.[13] The Indian tradition, states Moriz Winternitz, has favored the learning and the usage of multiple languages from the ancient times. Sanskrit was a spoken language in the educated and the elite classes, but it was also a language that must have been understood in a wider circle of society because the widely popular folk epics and stories such as the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, the Bhagavata Purana, the Panchatantra and many other texts are all in the Sanskrit language.[121] The Classical Sanskrit with its exacting grammar was thus the language of the Indian scholars and the educated classes, while others communicated with approximate or ungrammatical variants of it as well as other natural Indian languages.[13] Sanskrit, as the learned language of Ancient India, thus existed alongside the vernacular Prakrits.[13] Many Sanskrit dramas indicate that the language coexisted with the vernacular Prakrits. Centres in Varanasi, Paithan, Pune and Kanchipuram were centers of classical Sanskrit learning and public debates until the arrival of the colonial era.[122]

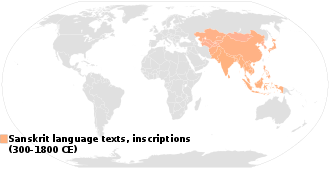

According to Étienne Lamotte—an Indologist and Buddhism scholar, Sanskrit became the dominant literary and inscriptional language because of its precision in communication. It was, states Lamotte, an ideal instrument for presenting ideas and as knowledge in Sanskrit multiplied so did its spread and influence.[123] Sanskrit was adopted voluntarily as a vehicle of high culture, arts, and profound ideas. Pollock disagrees with Lamotte, but concurs that Sanskrit's influence grew into what he terms as "Sanskrit Cosmopolis" over a region that included all of South Asia and much of southeast Asia. The Sanskrit language cosmopolis thrived beyond India between 300 and 1300 CE.[124]

Influence

— Foreword of Sanskrit Computational Linguistics (2009), Gérard Huet, Amba Kulkarni and Peter Scharf[125][126][note 11]

Sanskrit has been the predominant language of Hindu texts encompassing a rich tradition of philosophical and religious texts, as well as poetry, music, drama, scientific, technical and others.[128][129] It is the predominant language of one of the largest collection of historic manuscripts. The earliest known inscriptions in Sanskrit are from the 1st century BCE, such as the Ayodhya Inscription of Dhana and Ghosundi-Hathibada (Chittorgarh).[35]

Though developed and nurtured by scholars of orthodox schools of Hinduism, Sanskrit has been the language for some of the key literary works and theology of heterodox schools of Indian philosophies such as Buddhism and Jainism.[130][131] The structure and capabilities of the Classical Sanskrit language launched ancient Indian speculations about "the nature and function of language", what is the relationship between words and their meanings in the context of a community of speakers, whether this relationship is objective or subjective, discovered or is created, how individuals learn and relate to the world around them through language, and about the limits of language?[130][132] They speculated on the role of language, the ontological status of painting word-images through sound, and the need for rules so that it can serve as a means for a community of speakers, separated by geography or time, to share and understand profound ideas from each other.[132][note 12] These speculations became particularly important to the Mīmāṃsā and the Nyaya schools of Hindu philosophy, and later to Vedanta and Mahayana Buddhism, states Frits Staal—a scholar of Linguistics with a focus on Indian philosophies and Sanskrit.[130] Though written in a number of different scripts, the dominant language of Hindu texts has been Sanskrit. It or a hybrid form of Sanskrit became the preferred language of Mahayana Buddhism scholarship;[135] for example, one of the early and influential Buddhist philosophers, Nagarjuna (~200 CE), used Classical Sanskrit as the language for his texts.[136] According to Renou, Sanskrit had a limited role in the Theravada tradition (formerly known as the Hinayana) but the Prakrit works that have survived are of doubtful authenticity. Some of the canonical fragments of the early Buddhist traditions, discovered in the 20th century, suggest the early Buddhist traditions used an imperfect and reasonably good Sanskrit, sometimes with a Pali syntax, states Renou. The Mahāsāṃghika and Mahavastu, in their late Hinayana forms, used hybrid Sanskrit for their literature.[137] Sanskrit was also the language of some of the oldest surviving, authoritative and much followed philosophical works of Jainism such as the Tattvartha Sutra by Umaswati.[139]

The Sanskrit language has been one of the major means for the transmission of knowledge and ideas in Asian history. Indian texts in Sanskrit were already in China by 402 CE, carried by the influential Buddhist pilgrim Faxian who translated them into Chinese by 418 CE.[38] Xuanzang, another Chinese Buddhist pilgrim, learnt Sanskrit in India and carried 657 Sanskrit texts to China in the 7th century where he established a major center of learning and language translation under the patronage of Emperor Taizong.[143][144] By the early 1st millennium CE, Sanskrit had spread Buddhist and Hindu ideas to Southeast Asia,[15] parts of the East Asia[16] and the Central Asia.[17] It was accepted as a language of high culture and the preferred language by some of the local ruling elites in these regions.[145] According to the Dalai Lama, the Sanskrit language is a parent language that is at the foundation of many modern languages of India and the one that promoted Indian thought to other distant countries. In Tibetan Buddhism, states the Dalai Lama, Sanskrit language has been a revered one and called legjar lhai-ka or "elegant language of the gods". It has been the means of transmitting the "profound wisdom of Buddhist philosophy" to Tibet.[146]

The Sanskrit language created a pan-Indic accessibility to information and knowledge in the ancient and medieval times, in contrast to the Prakrit languages which were understood just regionally.[122][149] It created a cultural bond across the subcontinent.[149] As local languages and dialects evolved and diversified, Sanskrit served as the common language.[149] It connected scholars from distant parts of the Indian subcontinent such as Tamil Nadu and Kashmir, states Deshpande, as well as those from different fields of studies, though there must have been differences in its pronunciation given the first language of the respective speakers. The Sanskrit language brought Indic people together, particularly its elite scholars.[122] Some of these scholars of Indian history regionally produced vernacularized Sanskrit to reach wider audiences, as evidenced by texts discovered in Rajasthan, Gujarat, and Maharashtra. Once the audience became familiar with the easier to understand vernacularized version of Sanskrit, those interested could graduate from colloquial Sanskrit to the more advanced Classical Sanskrit. Rituals and the rites-of-passage ceremonies have been and continue to be the other occasions where a wide spectrum of people hear Sanskrit, and occasionally join in to speak some Sanskrit words such as "namah".[122]

Classical Sanskrit is the standard register as laid out in the grammar of Pāṇini, around the fourth century BCE.[150] Its position in the cultures of Greater India is akin to that of Latin and Ancient Greek in Europe. Sanskrit has significantly influenced most modern languages of the Indian subcontinent, particularly the languages of the northern, western, central and eastern Indian subcontinent.[26][27][28]

Decline

Sanskrit declined starting about and after the 13th century.[124][151] This coincides with the beginning of Islamic invasions of the Indian subcontinent to create, and thereafter expand the Muslim rule in the form of Sultanates, and later the Mughal Empire.[152] With the fall of Kashmir around the 13th century, a premier center of Sanskrit literary creativity, Sanskrit literature there disappeared,[153] perhaps in the "fires that periodically engulfed the capital of Kashmir" or the "Mongol invasion of 1320" states Sheldon Pollock.[154]:397–398 The Sanskrit literature which was once widely disseminated out of the northwest regions of the subcontinent, stopped after the 12th century.[154]:398 As Hindu kingdoms fell in the eastern and the South India, such as the great Vijayanagara Empire, so did Sanskrit.[153] There were exceptions and short periods of imperial support for Sanskrit, mostly concentrated during the reign of the tolerant Mughal emperor Akbar.[155] Muslim rulers patronized the Middle Eastern language and scripts found in Persia and Arabia, and the Indians linguistically adapted to this Persianization to gain employment with the Muslim rulers.[156] Hindu rulers such as Shivaji of the Maratha Empire, reversed the process, by re-adopting Sanskrit and re-asserting their socio-linguistic identity.[156][157][158] After Islamic rule disintegrated in the Indian subcontinent and the colonial rule era began, Sanskrit re-emerged but in the form of a "ghostly existence" in regions such as Bengal. This decline was the result of "political institutions and civic ethos" that did not support the historic Sanskrit literary culture.[153]

Scholars are divided on whether or when Sanskrit died. Western authors such as John Snelling state that Sanskrit and Pali are both dead Indian languages.[159] Indian authors such as M Ramakrishnan Nair state that Sanskrit was a dead language by the 1st millennium BCE.[160] Sheldon Pollock states that in some crucial way, "Sanskrit is dead".[154]:393 After the 12th century, the Sanskrit literary works were reduced to "reinscription and restatements" of ideas already explored, and any creativity was restricted to hymns and verses. This contrasted with the previous 1,500 years when "great experiments in moral and aesthetic imagination" marked the Indian scholarship using Classical Sanskrit, states Pollock.[154]:398

Other scholars state that the Sanskrit language did not die, only declined. Hanneder disagrees with Pollock, finding his arguments elegant but "often arbitrary". According to Hanneder, a decline or regional absence of creative and innovative literature constitutes a negative evidence to Pollock's hypothesis, but it is not positive evidence. A closer look at Sanskrit in the Indian history after the 12th century suggests that Sanskrit survived despite the odds. According to Hanneder,[161]

On a more public level the statement that Sanskrit is a dead language is misleading, for Sanskrit is quite obviously not as dead as other dead languages and the fact that it is spoken, written and read will probably convince most people that it cannot be a dead language in the most common usage of the term. Pollock's notion of the "death of Sanskrit" remains in this unclear realm between academia and public opinion when he says that "most observers would agree that, in some crucial way, Sanskrit is dead."[153]

%2C_Sanskrit%2C_Southern_Grantha_script%2C_Malayali_scribe_Kecavan%2C_sample_ii.jpg)

The Sanskrit language scholar Moriz Winternitz states, Sanskrit was never a dead language and it is still alive though its prevalence is lesser than ancient and medieval times. Sanskrit remains an integral part of Hindu journals, festivals, Ramlila plays, drama, rituals and the rites-of-passage.[162] Similarly, Brian Hatcher states that the "metaphors of historical rupture" by Pollock are not valid, that there is ample proof that Sanskrit was very much alive in the narrow confines of surviving Hindu kingdoms between the 13th and 18th centuries, and its reverence and tradition continues.[163]

Hanneder states that modern works in Sanskrit are either ignored or their "modernity" contested.[164]

According to Robert Goldman and Sally Sutherland, Sanskrit is neither "dead" nor "living" in the conventional sense. It is a special, timeless language that lives in the numerous manuscripts, daily chants and ceremonial recitations, a heritage language that Indians contextually prize and some practice.[165]

When the British introduced English to India in the 19th century, knowledge of Sanskrit and ancient literature continued to flourish as the study of Sanskrit changed from a more traditional style into a form of analytical and comparative scholarship mirroring that of Europe.[166]

Modern Indic languages

The relationship of Sanskrit to the Prakrit languages, particularly the modern form of Indian languages, is complex and spans about 3,500 years, states Colin Masica—a linguist specializing in South Asian languages. A part of the difficulty is the lack of sufficient textual, archaeological and epigraphical evidence for the ancient Prakrit languages with rare exceptions such as Pali, leading to a tendency of anachronistic errors.[167] Sanskrit and Prakrit languages may be divided into Old Indo-Aryan (1500 BCE–600 BCE), Middle Indo-Aryan (600 BCE–1000 CE) and New Indo-Aryan (1000 CE–current), each can further be subdivided in early, middle or second, and late evolutionary substages.[167]

Vedic Sanskrit belongs to the early Old Indo-Aryan while Classical Sanskrit to the later Old Indo-Aryan stage. The evidence for Prakrits such as Pali (Theravada Buddhism) and Ardhamagadhi (Jainism), along with Magadhi, Maharashtri, Sinhala, Sauraseni and Niya (Gandhari), emerge in the Middle Indo-Aryan stage in two versions—archaic and more formalized—that may be placed in early and middle substages of the 600 BCE–1000 CE period.[167] Two literary Indic languages can be traced to the late Middle Indo-Aryan stage and these are Apabhramsa and Elu (a form of literary Sinhalese). Numerous North, Central, Eastern and Western Indian languages, such as Hindi, Gujarati, Sindhi, Punjabi, Kashmiri, Nepali, Braj, Awadhi, Bengali, Assamese, Oriya, Marathi, and others belong to the New Indo-Aryan stage.[167]

There is an extensive overlap in the vocabulary, phonetics and other aspects of these New Indo-Aryan languages with Sanskrit, but it is neither universal nor identical across the languages. They likely emerged from a synthesis of the ancient Sanskrit language traditions and an admixture of various regional dialects. Each language has some unique and regionally creative aspects, with unclear origins. Prakrit languages do have a grammatical structure, but like the Vedic Sanskrit, it is far less rigorous than Classical Sanskrit. The roots of all Prakrit languages may be in the Vedic Sanskrit and ultimately the Indo-Aryan language, their structural details vary from the Classical Sanskrit.[29][167] It is generally accepted by scholars and widely believed in India that the modern Indic languages, such as Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi and Punjabi are descendants of the Sanskrit language.[168][169][170] Sanskrit, states Burjor Avari, can be described as "the mother language of almost all the languages of north India".[171]

Geographic distribution

The Sanskrit language's historic presence is attested across a wide geography beyond the Indian subcontinent. Inscriptions and literary evidence suggests that Sanskrit language was already being adopted in Southeast Asia and Central Asia in the 1st millennium CE, through monks, religious pilgrims and merchants.[172][173][174]

The Indian subcontinent has been the geographic range of the largest collection of the ancient and pre-18th-century Sanskrit manuscripts and inscriptions.[127] Beyond ancient India, significant collections of Sanskrit manuscripts and inscriptions have been found in China (particularly the Tibetan monasteries),[175][176] Myanmar,[177] Indonesia,[178] Cambodia,[179] Laos,[180] Vietnam,[181] Thailand,[182] and Malaysia.[180] Sanskrit inscriptions, manuscripts or its remnants, including some of the oldest known Sanskrit written texts, have been discovered in dry high deserts and mountainous terrains such as in Nepal,[183][184][note 13] Tibet,[176][185] Afghanistan,[186][187] Mongolia,[188] Uzbekistan,[189] Turkmenistan, Tajikistan,[189] and Kazakhstan.[190] Some Sanskrit texts and inscriptions have also been discovered in Korea and Japan.[191][192][193]

Official status

In India, Sanskrit is among the 22 official languages of India in the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution.[194] In 2010, Uttarakhand became the first state in India to make Sanskrit its second official language.[195] In 2019, Himachal Pradesh made Sanskrit its second official language, becoming the second state in India to do so.[196]

Phonology

Sanskrit shares many Proto-Indo-European phonological features, although it features a larger inventory of distinct phonemes. The consonantal system is the same, though it systematically enlarged the inventory of distinct sounds. For example, Sanskrit added a voiceless aspirated "tʰ", to the voiceless "t", voiced "d" and voiced aspirated "dʰ" found in PIE languages.[197]

The most significant and distinctive phonological development in Sanskrit is vowel-merger, states Stephanie Jamison—an Indo-European linguist specializing in Sanskrit literature.[197] The short *e, *o and *a, all merge as a (अ) in Sanskrit, while long *ē, *ō and *ā, all merge as long ā (आ). These mergers occurred very early and significantly impacted Sanskrit's morphological system.[197] Some phonological developments in it mirror those in other PIE languages. For example, the labiovelars merged with the plain velars as in other satem languages. The secondary palatalization of the resulting segments is more thorough and systematic within Sanskrit, states Jamison.[197] A series of retroflex dental stops were innovated in Sanskrit to more thoroughly articulate sounds for clarity. For example, unlike the loss of the morphological clarity from vowel contraction that is found in early Greek and related southeast European languages, Sanskrit deployed *y, *w, and *s intervocalically to provide morphological clarity.[197]

Vowels

The cardinal vowels (svaras) i (इ), u (उ), a (अ) distinguish length in Sanskrit, states Jamison.[198][199] The short a (अ) in Sanskrit is a closer vowel than ā, equivalent to schwa. The mid-vowels ē (ए) and ō (ओ) in Sanskrit are monophthongizations of the Indo-Iranian diphthongs *ai and *au. The Old Iranian language preserved *ai and *au.[198] The Sanskrit vowels are inherently long, though often transcribed e and o without the diacritic. The vocalic liquid r̥ in Sanskrit is a merger of PIE *r̥ and *l̥. The long r̥ is an innovation and it is used in a few analogically generated morphological categories.[198][200][201]

| Independent form | IAST/ ISO |

Independent form | IAST/ ISO | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kaṇṭhya (Guttural) |

अ | a | आ | ā | ||

| tālavya (Palatal) |

इ | i | ई | ī | ||

| oṣṭhya (Labial) |

उ | u | ऊ | ū | ||

| mūrdhanya (Retroflex) |

ऋ | ṛ/r̥ | ॠ | ṝ/r̥̄ | ||

| dantya (Dental) |

ऌ | ḷ/l̥ | (ॡ) | (ḹ/l̥̄)[203] | ||

| kaṇṭhatālavya (Palatoguttural) |

ए | e/ē | ऐ | ai | ||

| kaṇṭhoṣṭhya (Labioguttural) |

ओ | o/ō | औ | au | ||

| (consonantal allophones) | अं | aṃ/aṁ[204] | अः | aḥ[205] |

According to Masica, Sanskrit has four traditional semivowels, with which were classed, "for morphophonemic reasons, the liquids: y, r, l, and v; that is, as y and v were the non-syllabics corresponding to i, u, so were r, l in relation to r̥ and l̥".[206] The northwestern, the central and the eastern Sanskrit dialects have had a historic confusion between "r" and "l". The Paninian system that followed the central dialect preserved the distinction, likely out of reverence for the Vedic Sanskrit that distinguished the "r" and "l". However, the northwestern dialect only had "r", while the eastern dialect probably only had "l", states Masica. Thus literary works from different parts of ancient India appear inconsistent in their use of "r" and "l", resulting in doublets that is occasionally semantically differentiated.[206]

Consonants

Sanskrit possesses a symmetric consonantal phoneme structure based on how the sound is articulated, though the actual usage of these sounds conceals the lack of parallelism in the apparent symmetry possibly from historical changes within the language.[207]

| sparśa (Plosive) |

anunāsika (Nasal) |

antastha (Approximant) |

ūṣman/saṃgharṣhī (Fricative) | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voicing → | aghoṣa | ghoṣa | aghoṣa | ||||||||||||||||||

| Aspiration → | alpaprāṇa | mahāprāṇa | alpaprāṇa | mahāprāṇa | alpaprāṇa | mahāprāṇa | |||||||||||||||

| kaṇṭhya (Guttural) |

क | ka | /k/ | ख | kha | /kʰ/ | ग | ga | /g/ | घ | gha | /gʱ/ | ङ | ṅa | /ŋ/ | ह | ha | /ɦ/ | |||

| tālavya (Palatal) |

च | ca | /c/

/t͡ɕ/ |

छ | cha | /cʰ/

/t͡ɕʰ/ |

ज | ja | /ɟ/

/d͡ʑ/ |

झ | jha | /ɟʱ/

/d͡ʑʱ/ |

ञ | ña | /ɲ/ | य | ya | /j/ | श | śa | /ɕ/ |

| mūrdhanya (Retroflex) |

ट | ṭa | /ʈ/ | ठ | ṭha | /ʈʰ/ | ड | ḍa | /ɖ/ | ढ | ḍha | /ɖʱ/ | ण | ṇa | /ɳ/ | र | ra | /ɽ/ | ष | ṣa | /ʂ/ |

| dantya (Dental) |

त | ta | /t/ | थ | tha | /tʰ/ | द | da | /d/ | ध | dha | /dʱ/ | न | na | /n/ | ल | la | /l/ | स | sa | /s/ |

| oṣṭhya (Labial) |

प | pa | /p/ | फ | pha | /pʰ/ | ब | ba | /b/ | भ | bha | /bʱ/ | म | ma | /m/ | व | va | /ʋ/ | |||

Sanskrit had a series of retroflex stops. All the retroflexes in Sanskrit are in "origin conditioned alternants of dentals, though from the beginning of the language they have a qualified independence", states Jamison.[207]

Regarding the palatal plosives, the pronunciation is a matter of debate. In contemporary attestation, the palatal plosives are a regular series of palatal stops, supported by most Sanskrit sandhi rules. However, the reflexes in descendant languages, as well as a few of the sandhi rules regarding ch, could suggest an affricate pronunciation.

jh was a marginal phoneme in Sanskrit, hence its phonology is more difficult to reconstruct; it was more commonly employed in the Middle Indo-Aryan languages as a result of phonological processes resulting in the phoneme.

The palatal nasal is a conditioned variant of n occurring next to palatal obstruents.[207] The anusvara that Sanskrit deploys is a conditioned alternant of postvocalic nasals, under certain sandhi conditions.[208] Its visarga is a word-final or morpheme-final conditioned alternant of s and r under certain sandhi conditions.[208]

[The] order of Sanskrit sounds works along three principles: it goes from simple to complex; it goes from the back to the front of the mouth; and it groups similar sounds together. [...] Among themselves, both the vowels and consonants are ordered according to where in the mouth they are pronounced, going from back to front.

— A. M. Ruppel, The Cambridge Introduction to Sanskrit[209]

The voiceless aspirated series is also an innovation in Sanskrit but is significantly rarer than the other three series.[207]

While the Sanskrit language organizes sounds for expression beyond those found in the PIE language, it retained many features found in the Iranian and Balto-Slavic languages. An example of a similar process in all three, states Jamison, is the retroflex sibilant ʂ being the automatic product of dental s following i, u, r, and k (mnemonically "ruki").[208]

Phonological alternations, sandhi rules

Sanskrit deploys extensive phonological alternations on different linguistic levels through sandhi rules (literally, the rules of "putting together, union, connection, alliance"). This is similar to the English alteration of "going to" as gonna, states Jamison.[210] The Sanskrit language accepts such alterations within it, but offers formal rules for the sandhi of any two words next to each other in the same sentence or linking two sentences. The external sandhi rules state that similar short vowels coalesce into a single long vowel, while dissimilar vowels form glides or undergo diphthongization.[210] Among the consonants, most external sandhi rules recommend regressive assimilation for clarity when they are voiced. According to Jamison, these rules ordinarily apply at compound seams and morpheme boundaries.[210] In Vedic Sanskrit, the external sandhi rules are more variable than in Classical Sanskrit.[211]

The internal sandhi rules are more intricate and account for the root and the canonical structure of the Sanskrit word. These rules anticipate what are now known as the Bartholomae's law and Grassmann's law. For example, states Jamison, the "voiceless, voiced, and voiced aspirated obstruents of a positional series regularly alternate with each other (p ≈ b ≈ bʰ; t ≈ d ≈ dʰ, etc.; note, however, c ≈ j ≈ h), such that, for example, a morpheme with an underlying voiced aspirate final may show alternants with all three stops under differing internal sandhi conditions".[212] The velar series (k, g, gʰ) alternate with the palatal series (c, j, h), while the structural position of the palatal series is modified into a retroflex cluster when followed by dental. This rule create two morphophonemically distinct series from a single palatal series.[212]

Vocalic alternations in the Sanskrit morphological system is termed "strengthening", and called guna and vriddhi in the preconsonantal versions. There is an equivalence to terms deployed in Indo-European descriptive grammars, wherein Sanskrit's unstrengthened state is same as the zero-grade, guna corresponds to normal-grade, while vriddhi is same as the lengthened-state.[213] The qualitative ablaut is not found in Sanskrit just like it is absent in Iranian, but Sanskrit retains quantitative ablaut through vowel strengthening.[213] The transformations between unstrengthened to guna is prominent in the morphological system, states Jamison, while vriddhi is a particularly significant rule when adjectives of origin and appurtenance are derived. The manner in which this is done slightly differs between the Vedic and the Classical Sanskrit.[213][214]

Sanskrit grants a very flexible syllable structure, where they may begin or end with vowels, be single consonants or clusters. Similarly, the syllable may have an internal vowel of any weight. The Vedic Sanskrit shows traces of following the Sievers-Edgerton Law, but Classical Sanskrit doesn't. Vedic Sanskrit has a pitch accent system, states Jamison, which were acknowledged by Panini, but in his Classical Sanskrit the accents disappear.[215] Most Vedic Sanskrit words have one accent. However, this accent is not phonologically predictable, states Jamison.[215] It can fall anywhere in the word and its position often conveys morphological and syntactic information.[215] According to Masica, the presence of an accent system in Vedic Sanskrit is evidenced from the markings in the Vedic texts. This is important because of Sanskrit's connection to the PIE languages and comparative Indo-European linguistics.[216]

Sanskrit, like most early Indo-European languages, lost the so-called "laryngeal consonants (cover-symbol *H) present in the Proto-Indo-European", states Jamison.[215] This significantly impacted the evolutionary path of the Sanskrit phonology and morphology, particularly in the variant forms of roots.[217]

Pronunciation

Because Sanskrit is not anyone's native language, it does not have a fixed pronunciation. People tend to pronounce it as they do their native language. The articles on Hindustani, Marathi, Nepali, Oriya and Bengali phonology will give some indication of the variation that is encountered. When Sanskrit was a spoken language, its pronunciation varied regionally and also over time. Nonetheless, Panini described the sound system of Sanskrit well enough that people have a fairly good idea of what he intended.

| Transcription | Goldman (2002)[218] |

Cardona (2003)[219] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| a | ɐ | ɐ | |

| ā | aː | aː | |

| i | ɪ | ɪ | |

| ī | iː | iː | |

| u | ʊ | ʊ | |

| ū | uː | uː | |

| r̥ | ɽɪ | ɽɪ | ᵊɾᵊ or ᵊɽᵊ[220] |

| r̥̄ | ɽiː | ɽiː?[221] | ?[221] |

| l̥ | lɪ | ?[222] | [223] |

| ē | eː | eː | eː |

| ai | ai | ai | ɐi or ɛi |

| ō | oː | oː | oː |

| au | au | au | ɐu or ɔu |

| aṃ | ɐ̃, ɐN | ɐ̃, ɐN[224] | |

| aḥ | ɐh | ɐhɐ[225] | ɐh |

| k | k | k | |

| kh | kʰ | kʰ | |

| g | ɡ | ɡ | |

| gh | ɡʱ | ɡʱ | |

| ṅ | ŋ | ŋ | |

| h | ɦ | ɦ | ɦ |

| c | t͡ɕ | t͡ɕ | |

| ch | t͡ɕʰ | t͡ɕʰ | |

| j | d͡ʑ | d͡ʑ | |

| jh | d͡ʑʱ | d͡ʑʱ | |

| ñ | n | n | |

| y | j | j | j |

| ś | ɕ | ɕ | ɕ |

| ṭ | t̠ | t̠ | |

| ṭh | t̠ʰ | t̠ʰ | |

| ḍ | d̠ | d̠ | |

| ḍh | d̠ʱ | d̠ʱ | |

| ṇ | n̠ | n̠ | |

| r | ɽ | ɾ̪, ɾ or ɽ | |

| ṣ | s̠ | s̠ | ʂ |

| t | t̪ | t̪ | |

| th | t̪ʰ | t̪ʰ | |

| d | d̪ | d̪ | |

| dh | d̪ʱ | d̪ʱ | |

| n | n̪ | n̪ | |

| l | l | l | l̪ |

| s | s | s | s̪ |

| p | p | p | |

| ph | pʰ | pʰ | |

| b | b | b | |

| bh | bʱ | bʱ | |

| m | m | m | |

| v | ʋ | ʋ | ʋ |

| stress | (ante)pen- ultimate[226] |

Morphology

The basis of Sanskrit morphology is the root, states Jamison, "a morpheme bearing lexical meaning".[227] The verbal and nominal stems of Sanskrit words are derived from this root through the phonological vowel-gradation processes, the addition of affixes, verbal and nominal stems. It then adds an ending to establish the grammatical and syntactic identity of the stem. According to Jamison, the "three major formal elements of the morphology are (i) root, (ii) affix, and (iii) ending; and they are roughly responsible for (i) lexical meaning, (ii) derivation, and (iii) inflection respectively".[228]

A Sanskrit word has the following canonical structure:[227]

- Root + Affix

0-n + Ending

0–1

The root structure has certain phonological constraints. Two of the most important constraints of a "root" is that it does not end in a short "a" (अ) and that it is monosyllabic.[227] In contrast, the affixes and endings commonly do. The affixes in Sanskrit are almost always suffixes, with exceptions such as the augment "a-" added as prefix to past tense verb forms and the "-na/n-" infix in single verbal present class, states Jamison.[227]

A verb in Sanskrit has the following canonical structure:[229]

- Root + Suffix

Tense-Aspect + Suffix

Mood + Ending

Personal-Number-Voice

According to Ruppel, verbs in Sanskrit express the same information as other Indo-European languages such as English.[230] Sanskrit verbs describe an action or occurrence or state, its embedded morphology informs as to "who is doing it" (person or persons), "when it is done" (tense) and "how it is done" (mood, voice). The Indo-European languages differ in the detail. For example, the Sanskrit language attaches the affixes and ending to the verb root, while the English language adds small independent words before the verb. In Sanskrit, these elements co-exist within the word.[230][note 16]

| Sanskrit word equivalent | ||

|---|---|---|

| English expression | IAST/ISO | Devanagari |

| you carry | bharasi | भरसि |

| they carry | bharanti | भरन्ति |

| you will carry | bhariṣyasi | भरिष्यसि |

Both verbs and nouns in Sanskrit are either thematic or athematic, states Jamison.[232] Guna (strengthened) forms in the active singular regularly alternate in athematic verbs. The finite verbs of Classical Sanskrit have the following grammatical categories: person, number, voice, tense-aspect, and mood. According to Jamison, a portmanteau morpheme generally expresses the person-number-voice in Sanskrit, and sometimes also the ending or only the ending. The mood of the word is embedded in the affix.[232]

These elements of word architecture are the typical building blocks in Classical Sanskrit, but in Vedic Sanskrit these elements fluctuate and are unclear. For example, in the Rigveda preverbs regularly occur in tmesis, states Jamison, which means they are "separated from the finite verb".[227] This indecisiveness is likely linked to Vedic Sanskrit's attempt to incorporate accent. With nonfinite forms of the verb and with nominal derivatives thereof, states Jamison, "preverbs show much clearer univerbation in Vedic, both by position and by accent, and by Classical Sanskrit, tmesis is no longer possible even with finite forms".[227]

While roots are typical in Sanskrit, some words do not follow the canonical structure.[228] A few forms lack both inflection and root. Many words are inflected (and can enter into derivation) but lack a recognizable root. Examples from the basic vocabulary include kinship terms such as mātar- (mother), nas- (nose), śvan- (dog). According to Jamison, pronouns and some words outside the semantic categories also lack roots, as do the numerals. Similarly, the Sanskrit language is flexible enough to not mandate inflection.[228]

The Sanskrit words can contain more than one affix that interact with each other. Affixes in Sanskrit can be athematic as well as thematic, according to Jamison.[233] Athematic affixes can be alternating. Sanskrit deploys eight cases, namely nominative, accusative, instrumental, dative, ablative, genitive, locative, vocative.[233]

Stems, that is "root + affix", appear in two categories in Sanskrit: vowel stems and consonant stems. Unlike some Indo-European languages such as Latin or Greek, according to Jamison, "Sanskrit has no closed set of conventionally denoted noun declensions". Sanskrit includes a fairly large set of stem-types.[234] The linguistic interaction of the roots, the phonological segments, lexical items and the grammar for the Classical Sanskrit consist of four Paninian components. These, states Paul Kiparsky, are the Astadhyaayi, a comprehensive system of 4,000 grammatical rules, of which a small set are frequently used; Sivasutras, an inventory of anubandhas (markers) that partition phonological segments for efficient abbreviations through the pratyharas technique; Dhatupatha, a list of 2,000 verbal roots classified by their morphology and syntactic properties using diacritic markers, a structure that guides its writing systems; and, the Ganapatha, an inventory of word groups, classes of lexical systems.[235] There are peripheral adjuncts to these four, such as the Unadisutras, which focus on irregularly formed derivatives from the roots.[235]

Sanskrit morphology is generally studied in two broad fundamental categories: the nominal forms and the verbal forms. These differ in the types of endings and what these endings mark in the grammatical context.[228] Pronouns and nouns share the same grammatical categories, though they may differ in inflection. Verb-based adjectives and participles are not formally distinct from nouns. Adverbs are typically frozen case forms of adjectives, states Jamison, and "nonfinite verbal forms such as infinitives and gerunds also clearly show frozen nominal case endings".[228]

Tense and voice

The Sanskrit language includes five tenses: present, future, past imperfect, past aorist and past perfect.[231] It outlines three types of voices: active, passive and the middle.[231] The middle is also referred to as the mediopassive, or more formally in Sanskrit as parasmaipada (word for another) and atmanepada (word for oneself).[229]

| Active | Middle (Mediopassive) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Singular | Dual | Plural | Singular | Dual | Plural |

| 1st | -mi | -vas | -mas | -e | -vahe | -mahe |

| 2nd | -si | -thas | -tha | -se | -āthe | -dhve |

| 3rd | -ti | -tas | -anti | -te | -āte | -ante |

The paradigm for the tense-aspect system in Sanskrit is the three-way contrast between the "present", the "aorist" and the "perfect" architecture.[236] Vedic Sanskrit is more elaborate and had several additional tenses. For example, the Rigveda includes perfect and a marginal pluperfect. Classical Sanskrit simplifies the "present" system down to two tenses, the perfect and the imperfect, while the "aorist" stems retain the aorist tense and the "perfect" stems retain the perfect and marginal pluperfect.[236] The classical version of the language has elaborate rules for both voice and the tense-aspect system to emphasize clarity, and this is more elaborate than in other Indo-European languages. The evolution of these systems can be seen from the earliest layers of the Vedic literature to the late Vedic literature.[237]

Gender, mood

Sanskrit recognizes three numbers—singular, dual, and plural.[233] The dual is a fully functioning category, used beyond naturally paired objects such as hands or eyes, extending to any collection of two. The elliptical dual is notable in the Vedic Sanskrit, according to Jamison, where a noun in the dual signals a paired opposition.[233] Illustrations include dyāvā (literally, "the two heavens" for heaven-and-earth), mātarā (literally, "the two mothers" for mother-and-father).[233] A verb may be singular, dual or plural, while the person recognized in the language are forms of "I", "you", "he/she/it", "we" and "they".[231]

There are three persons in Sanskrit: first, second and third.[229] Sanskrit uses the 3×3 grid formed by the three numbers and the three persons parameters as the paradigm and the basic building block of its verbal system.[237]

The Sanskrit language incorporates three genders: feminine, masculine and neuter.[233] All nouns have inherent gender, but with some exceptions, personal pronouns have no gender. Exceptions include demonstrative and anaphoric pronouns.[233] Derivation of a word is used to express the feminine. Two most common derivations come from feminine-forming suffixes, the -ā- (आ, Rādhā) and -ī- (ई, Rukmīnī). The masculine and neuter are much simpler, and the difference between them is primarily inflectional.[233][238] Similar affixes for the feminine are found in many Indo-European languages, states Burrow, suggesting links of the Sanskrit to its PIE heritage.[239]

Pronouns in Sanskrit include the personal pronouns of the first and second persons, unmarked for gender, and a larger number of gender-distinguishing pronouns and adjectives.[232] Examples of the former include ahám (first singular), vayám (first plural) and yūyám (second plural). The latter can be demonstrative, deictic or anaphoric.[232] Both the Vedic and Classical Sanskrit share the sá/tám pronominal stem, and this is the closest element to a third person pronoun and an article in the Sanskrit language, states Jamison.[232]

Indicative, potential and imperative are the three mood forms in Sanskrit.[231]

Prosody, meter

The Sanskrit language formally incorporates poetic metres.[240] By the late Vedic era, this developed into a field of study and it was central to the composition of the Hindu literature including the later Vedic texts. This study of Sanskrit prosody is called chandas and considered as one of the six Vedangas, or limbs of Vedic studies.[240][241]

Sanskrit prosody includes linear and non-linear systems.[242] The system started off with seven major metres, according to Annette Wilke and Oliver Moebus, called the "seven birds" or "seven mouths of Brihaspati", and each had its own rhythm, movements and aesthetics wherein a non-linear structure (aperiodicity) was mapped into a four verse polymorphic linear sequence.[243] A syllable in Sanskrit is classified as either laghu (light) or guru (heavy). This classification is based on a matra (literally, "count, measure, duration"), and typically a syllable that ends in a short vowel is a light syllable, while those that end in consonant, anusvara or visarga are heavy. The classical Sanskrit found in Hindu scriptures such as the Bhagavad Gita and many texts are so arranged that the light and heavy syllables in them follow a rhythm, though not necessarily a rhyme.[244][245][note 19]

Sanskrit metres include those based on a fixed number of syllables per verse, and those based on fixed number of morae per verse.[247] The Vedic Sanskrit employs fifteen metres, of which seven are common, and the most frequent are three (8-, 11- and 12-syllable lines).[248] The Classical Sanskrit deploys both linear and non-linear metres, many of which are based on syllables and others based on diligently crafted verses based on repeating numbers of morae (matra per foot).[248]

There is no word without meter,

nor is there any meter without words.

—Natya Shastra[249]

Meter and rhythm is an important part of the Sanskrit language. It may have played a role in helping preserve the integrity of the message and Sanskrit texts. The verse perfection in the Vedic texts such as the verse Upanishads[note 20] and post-Vedic Smriti texts are rich in prosody. This feature of the Sanskrit language led some Indologists from the 19th century onwards to identify suspected portions of texts where a line or sections are off the expected metre.[250][251][note 21]

The meter-feature of the Sanskrit language embeds another layer of communication to the listener or reader. A change in metres has been a tool of literary architecture and an embedded code to inform the reciter and audience that it marks the end of a section or chapter.[255] Each section or chapter of these texts uses identical metres, rhythmically presenting their ideas and making it easier to remember, recall and check for accuracy.[255] Authors coded a hymn's end by frequently using a verse of a metre different than that used in the hymn's body.[255] However, Hindu tradition does not use the Gayatri metre to end a hymn or composition, possibly because it has enjoyed a special level of reverence in Hinduism.[255]

Writing system

.jpg)

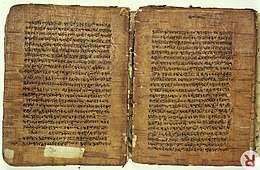

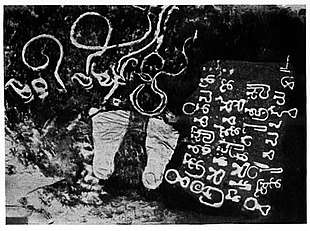

The early history of writing Sanskrit and other languages in ancient India is a problematic topic despite a century of scholarship, states Richard Salomon—an epigraphist and Indologist specializing in Sanskrit and Pali literature.[256] The earliest possible script from the Indian subcontinent is from the Indus Valley Civilization (3rd/2nd millennium BCE), but this script – if it is a script – remains undeciphered. If any scripts existed in the Vedic period, they have not survived. Scholars generally accept that Sanskrit was spoken in an oral society, and that an oral tradition preserved the extensive Vedic and Classical Sanskrit literature.[257] Other scholars such as Jack Goody state that the Vedic Sanskrit texts are not the product of an oral society, basing this view by comparing inconsistencies in the transmitted versions of literature from various oral societies such as the Greek, Serbian, and other cultures, then noting that the Vedic literature is too consistent and vast to have been composed and transmitted orally across generations, without being written down.[258][259]

Lipi is the term in Sanskrit which means "writing, letters, alphabet". It contextually refers to scripts, the art or any manner of writing or drawing.[95] The term, in the sense of a writing system, appears in some of the earliest Buddhist, Hindu, and Jaina texts. Pāṇini's Astadhyayi, composed sometime around the 5th or 4th century BCE, for example, mentions lipi in the context of a writing script and education system in his times, but he does not name the script.[95][96][260] Several early Buddhist and Jaina texts, such as the Lalitavistara Sūtra and Pannavana Sutta include lists of numerous writing scripts in ancient India.[note 22] The Buddhist texts list the sixty four lipi that the Buddha knew as a child, with the Brahmi script topping the list. "The historical value of this list is however limited by several factors", states Salomon. The list may be a later interpolation.[262][note 23] The Jain canonical texts such as the Pannavana Sutta—probably older than the Buddhist texts—list eighteen writing systems, with the Brahmi topping the list and Kharotthi (Kharoshthi) listed as fourth. The Jaina text elsewhere states that the "Brahmi is written in 18 different forms", but the details are lacking.[264] However, the reliability of these lists has been questioned and the empirical evidence of writing systems in the form of Sanskrit or Prakrit inscriptions dated prior to the 3rd century BCE has not been found. If the ancient surface for writing Sanskrit was palm leaves, tree bark and cloth—the same as those in later times, these have not survived.[265][note 24] According to Salomon, many find it difficult to explain the "evidently high level of political organization and cultural complexity" of ancient India without a writing system for Sanskrit and other languages.[265][note 25]

The oldest datable writing systems for Sanskrit are the Brāhmī script, the related Kharoṣṭhī script and the Brahmi derivatives.[268][269] The Kharosthi was used in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent and it became extinct, while the Brahmi was used in all over the subcontinent along with regional scripts such as Old Tamil.[270] Of these, the earliest records in the Sanskrit language are in Brahmi, a script that later evolved into numerous related Indic scripts for Sanskrit, along with Southeast Asian scripts (Burmese, Thai, Lao, Khmer, others) and many extinct Central Asian scripts such as those discovered along with the Kharosthi in the Tarim Basin of western China and in Uzbekistan.[271] The most extensive inscriptions that have survived into the modern era are the rock edicts and pillar inscriptions of the 3rd-century BCE Mauryan emperor Ashoka, but these are not in Sanskrit.[272][note 26]

Scripts

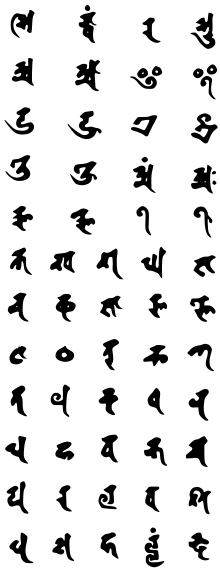

Over the centuries, and across countries, a number of scripts have been used to write Sanskrit.

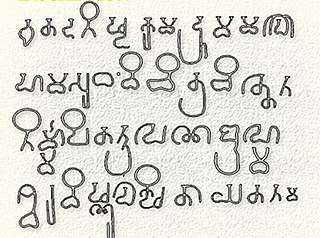

Brahmi script

The Brahmi script for writing Sanskrit is a "modified consonant-syllabic" script. The graphic syllable is its basic unit, and this consists of a consonant with or without diacritic modifications.[274] Since the vowel is an integral part of the consonants, and given the efficiently compacted, fused consonant cluster morphology for Sanskrit words and grammar, the Brahmi and its derivative writing systems deploy ligatures, diacritics and relative positioning of the vowel to inform the reader how the vowel is related to the consonant and how it is expected to be pronounced for clarity.[269][275][note 28] This feature of Brahmi and its modern Indic script derivatives makes it difficult to classify it under the main script types used for the writing systems for most of the world's languages, namely logographic, syllabic and alphabetic.[269]

The Brahmi script evolved into "a vast number of forms and derivatives", states Richard Salomon, and in theory, Sanskrit "can be represented in virtually any of the main Brahmi-based scripts and in practice it often is".[276] Sanskrit does not have a native script. Being a phonetic language, it can be written in any precise script that efficiently maps unique human sounds to unique symbols. From the ancient times, it has been written in numerous regional scripts in South and Southeast Asia. Most of these are descendants of the Brahmi script.[277] The earliest datable varnamala Brahmi alphabet system, found in later Sanskrit texts, is from the 2nd century BCE, in the form of a terracotta plaque found in Sughana, Haryana. It shows a "schoolboy's writing lessons", states Salomon.[278][279]

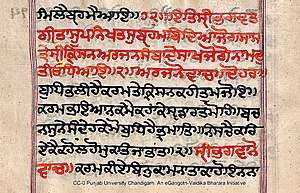

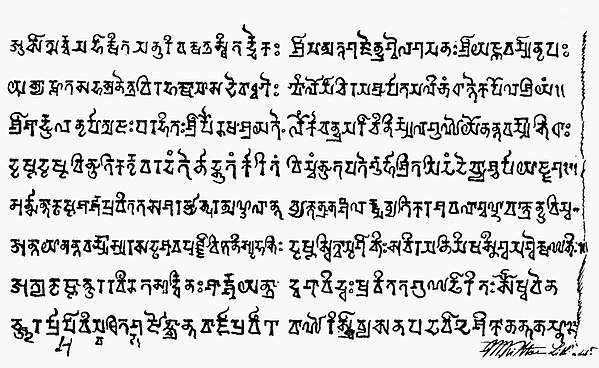

Nagari script

Many modern era manuscripts are written and available in the Nagari script, whose form is attestable to the 1st millennium CE.[280] The Nagari script is the ancestor of Devanagari (north India), Nandinagari (south India) and other variants. The Nāgarī script was in regular use by 7th century CE, and had fully evolved into Devanagari and Nandinagari[281] scripts by about the end of the first millennium of the common era.[282][283] The Devanagari script, states Banerji, became more popular for Sanskrit in India since about the 18th century.[284] However, Sanskrit does have special historical connection to the Nagari script as attested by the epigraphical evidence.[285]

The Nagari script has been thought as a north Indian script for Sanskrit as well as the regional languages such as Hindi, Marathi and Nepali. However, it has had a "supra-local" status as evidenced by 1st-millennium CE epigraphy and manuscripts discovered all over India and as far as Sri Lanka, Burma, Indonesia and in its parent form called the Siddhamatrka script found in manuscripts of East Asia.[286] The Sanskrit and Balinese languages Sanur inscription on Belanjong pillar of Bali (Indonesia), dated to about 914 CE, is in part in the Nagari script.[287]

The Nagari script used for Classical Sanskrit has the fullest repertoire of characters consisting of fourteen vowels and thirty three consonants. For the Vedic Sanskrit, it has two more allophonic consonantal characters (the intervocalic ळ ḷa, and ळ्ह ḷha).[286] To communicate phonetic accuracy, it also includes several modifiers such as the anusvara dot and the visarga double dot, punctuation symbols and others such as the halanta sign.[286]

Other writing systems

Other scripts such as Gujarati, Bangla, Odia and major south Indian scripts, states Salomon, "have been and often still are used in their proper territories for writing Sanskrit".[280] These and many Indian scripts look different to the untrained eye, but the differences between Indic scripts is "mostly superficial and they share the same phonetic repertoire and systemic features", states Salomon.[288] They all have essentially the same set of eleven to fourteen vowels and thirty-three consonants as established by the Sanskrit language and attestable in the Brahmi script. Further, a closer examination reveals that they all have the similar basic graphic principles, the same varnamala (literally, "garland of letters") alphabetic ordering following the same logical phonetic order, easing the work of historic skilled scribes writing or reproducing Sanskrit works across the Indian subcontinent.[289][note 29] The Sanskrit language written in some Indic scripts exaggerate angles or round shapes, but this serves only to mask the underlying similarities. Nagari script favours symmetry set with squared outlines and right angles. In contrast, Sanskrit written in the Bangla script emphasizes the acute angles while the neighbouring Odia script emphasizes rounded shapes and uses cosmetically appealing "umbrella-like curves" above the script symbols.[291]

In the south, where Dravidian languages predominate, scripts used for Sanskrit include the Kannada, Telugu, Malayalam and Grantha alphabets.

Transliteration schemes, Romanisation

Since the late 18th century, Sanskrit has been transliterated using the Latin alphabet. The system most commonly used today is the IAST (International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration), which has been the academic standard since 1888. ASCII-based transliteration schemes have also evolved because of difficulties representing Sanskrit characters in computer systems. These include Harvard-Kyoto and ITRANS, a transliteration scheme that is used widely on the Internet, especially in Usenet and in email, for considerations of speed of entry as well as rendering issues. With the wide availability of Unicode-aware web browsers, IAST has become common online. It is also possible to type using an alphanumeric keyboard and transliterate to Devanagari using software like Mac OS X's international support.

European scholars in the 19th century generally preferred Devanagari for the transcription and reproduction of whole texts and lengthy excerpts. However, references to individual words and names in texts composed in European Languages were usually represented with Roman transliteration. From the 20th century onwards, because of production costs, textual editions edited by Western scholars have mostly been in Romanised transliteration.[292]

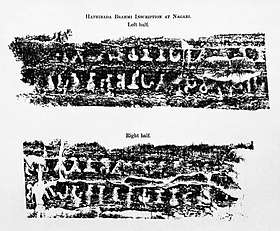

Epigraphy

The earliest known stone inscriptions in Sanskrit are in the Brahmi script from the first century BCE.[35][note 30][note 31] These include the Ayodhyā (Uttar Pradesh) and Hāthībādā-Ghosuṇḍī (near Chittorgarh, Rajasthan) inscriptions.[35][295] Both of these, states Salomon, are "essentially standard" and "correct Sanskrit", with a few exceptions reflecting an "informal Sanskrit usage".[35] Other important Hindu inscriptions dated to the 1st century BCE, in relatively accurate classical Sanskrit and Brahmi script are the Yavanarajya inscription on a red sandstone slab and the long Naneghat inscription on the wall of a cave rest stop in the Western Ghats.[296]

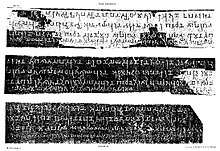

Besides these few examples from the 1st century BCE, the earliest Sanskrit and hybrid dialect inscriptions are found in Mathura (Uttar Pradesh).[297] These date to the 1st and 2nd century CE, states Salomon, from the time of the Indo-Scythian Northern Satraps and the subsequent Kushan Empire.[note 32] These are also in the Brahmi script.[299] The earliest of these, states Salomon, are attributed to Ksatrapa Sodasa from the early years of 1st century CE. Of the Mathura inscriptions, the most significant is the Mora Well Inscription.[299] In a manner similar to the Hathibada inscription, the Mora well inscription is a dedicatory inscription and is linked to the cult of the Vrishni heroes: it mentions a stone shrine (temple), pratima (murti, images) and calls the five Vrishnis as bhagavatam.[299][300] There are many other Mathura Sanskrit inscriptions in Brahmi script overlapping the era of Indo-Scythian Northern Satraps and early Kushanas.[301] Other significant 1st-century inscriptions in reasonably good classical Sanskrit in the Brahmi script include the Vasu Doorjamb Inscription and the Mountain Temple inscription.[302] The early ones are related to the Brahmanical, except for the inscription from Kankali Tila which may be Jaina, but none are Buddhist.[303][304] A few of the later inscriptions from the 2nd century CE include Buddhist Sanskrit, while others are in "more or less" standard Sanskrit and related to the Brahmanical tradition.[305]

In Maharashtra and Gujarat, Brahmi script Sanskrit inscriptions from the early centuries of the common era exist at the Nasik Caves site, near the Girnar mountain of Junagadh and elsewhere such as at Kanakhera, Kanheri, and Gunda.[306] The Nasik inscription dates to the mid-1st century CE, is a fair approximation of standard Sanskrit and has hybrid features.[306] The Junagadh rock inscription of Western Satraps ruler Rudradaman I (c. 150 CE, Gujarat) is the first long poetic-style inscription in "more or less" standard Sanskrit that has survived into the modern era. It represents a turning point in the history of Sanskrit epigraphy, states Salomon.[307][note 33] Though no similar inscriptions are found for about two hundred years after the Rudradaman reign, it is important because its style is the prototype of the eulogy-style Sanskrit inscriptions found in the Gupta Empire era.[307] These inscriptions are also in the Brahmi script.[308]

The Nagarjunakonda inscriptions are the earliest known substantial South Indian Sanskrit inscriptions, probably from the late 3rd century or early 4th century CE, or both.[309] These inscriptions are related to Buddhism and the Shaivism tradition of Hinduism.[310] A few of these inscriptions from both traditions are verse-style in the classical Sanskrit language, while some such as the pillar inscription is written in prose and a hybridized Sanskrit language.[309] An earlier hybrid Sanskrit inscription found on Amaravati slab is dated to the late 2nd century, while a few later ones include Sanskrit inscriptions along with Prakrit inscriptions related to Hinduism and Buddhism.[311] After the 3rd century CE, Sanskrit inscriptions dominate and many have survived.[312] Between the 4th and 7th centuries CE, south Indian inscriptions are exclusively in the Sanskrit language.[313] In the eastern regions of the Indian subcontinent, scholars report minor Sanskrit inscriptions from the 2nd century, these being fragments and scattered. The earliest substantial true Sanskrit language inscription of Susuniya (West Bengal) is dated to the 4th century.[314] Elsewhere, such as Dehradun (Uttarakhand), inscriptions in more or less correct classical Sanskrit inscriptions are dated to the 3rd century.[314]

According to Salomon, the 4th-century reign of Samudragupta was the turning point when the classical Sanskrit language became established as the "epigraphic language par excellence" of the Indian world.[315] These Sanskrit language inscriptions are either "donative" or "panegyric" records. Generally in accurate classical Sanskrit, they deploy a wide range of regional Indic writing systems extant at the time.[316] They record the donation of a temple or stupa, images, land, monasteries, pilgrim's travel record, public infrastructure such as water reservoir and irrigation measures to prevent famine. Others praise the king or the donor in lofty poetic terms.[317] The Sanskrit language of these inscriptions is written on stone, various metals, terracotta, wood, crystal, ivory, shell and cloth.[318][note 34]