Rudradaman I

Rudradāman I (r. 130–150) was a Śaka ruler from the Western Kshatrapas dynasty. He was the grandson of the king Caṣṭana.[1] Rudradāman I was instrumental in the decline of the Sātavāhana Empire.[2] Rudradāman I took up the title of Maha-kshtrapa ("Great Satrap"), after he became the king and then strengthened his kingdom.

| Rudradāman I | |

|---|---|

| Western Satrap | |

Rudradāman I coin, with corrupted Greek legend. British Museum. | |

| Reign | 130–150 CE |

Obv: Bust of Rudradāman, with corrupted Greek legend "OVONIΛOOCVΛCHΛNO".

Rev: Three-arched hill or Chaitya with river, crescent and sun. Brahmi legend: "Rajno Ksatrapasa Jayadamasaputrasa Rajno Mahaksatrapasa Rudradamasa": "King and Great Satrap Rudradaman, son of King and Satrap Jayadaman"

16mm, 2.0 grams.

Victory over the Sātavāhanas

He maintained matrimonial relationships with Sātavāhanas and conceded the country of Aparanta to Vashishtiputra Satakarni, his son-in-law and younger son of Gautamiputra Satakarni, as dowry. In spite of the matrimonial link, at least two wars took place between them wherein he defeated Sātavāhanas but spared the life of Satakarni (probably, Vashishtiputra Satakarni), essentially because of their relationship.[2][3] However, it is not known who was the aggressor in either of the wars and whether there were more wars between them.

"Rudradaman (...) who obtained good report because he, in spite of having twice in fair fight completely defeated Satakarni, the lord of Dakshinapatha, on account of the nearness of their connection did not destroy him."

As a result of his victories, Rudradāman regained all the former territories previously held by Nahapana, except for the southern territory of Poona and Nasik.[7] Sātavāhana dominions were limited to their original base in the Deccan and eastern central India around Amaravati:[2]

"Rudradaman (...) who is the lord of the whole of eastern and western Akaravanti (Akara: East Malwa and Avanti: West Malwa), the Anupa country, Anarta, Surashtra, Svabhra (northern Gujarat) Maru (Marwar), Kachchha (Cutch), Sindhu-Sauvira (Sindh and Multan districts), Kukura (Eastern Rajputana), Aparanta ("Western Border" - Northern Konkan), Nishada (an aboriginal tribe, Malwa and parts of Central India) and other territories gained by his own valour, the towns, marts and rural parts of which are never troubled by robbers, snakes, wild beasts, diseases and the like, where all subjects are attached to him, (and) where through his might the objects of [religion], wealth and pleasure [are duly attained]".

While most of the scholars, following Rapson believe that Rudradāman ruled from Ujjain, there is no such evidence to support this. In fact, there is evidence to prove the contrary:

- Jain sources mention that after Nahapana (40 years) and Gardabhilas (15 years), Śakas will rule Ujjain but for only four years. Caṣṭana no doubt has ruled Ujjain but he must have ruled it only for four years. His son Jayadāman (a Kshatrapa as against Caṣṭana being a Mahaksatrapa) was an ineffectual king and lost most of the territory won by Caṣṭana. This must have included all important Ujjain as well.

- Natural History of Claudius Ptolemy in 160 CE record Caṣṭana as the king of Avanti while it is known that it is Rudradāman who was ruling between 130 and 150 CE. Ptolemy was obviously referring only to the last best known ruler and if Rudradāman was ruling Avanti, he would have mentioned him, since he was certainly well known through his conquests.

- Truly speaking, Rudradāman made no reference to Avanti. He said he conquered Eastern and Western Akaravanti (Eastern Malwa) - Western Akaravanti being land lying east to Bhopal, which does not include any western part of Malwa or Avanti. Akaravanti, earlier called as Sudarsana, comprised only Eastern Malwa. Western Akaravanti does not refer to Avanti.

Other facts

.jpg)

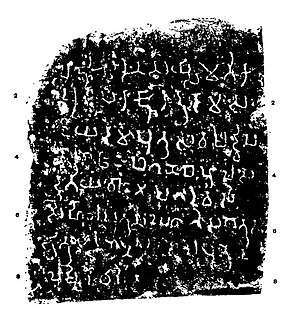

The Sanskrit Junagadh inscription dated 150 CE[9] credits Rudradāman I with supporting the cultural arts and Sanskrit literature and repairing the dam built by the Mauryans. He in fact repaired the embankments of the lake Sudarśana, which was constructed by the Mauryas for checking floods.

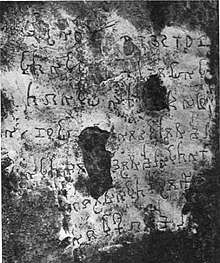

Rudradāman fought many a battle against the Sātavāhanas (or the Āndhras) and Vashishtiputra Satakarni, the son of the Āndhra king Pulamayi, in an effort to end the hostilities, married the daughter of Rudradāman.[2] The inscription relating the marriage between Rudradāman's daughter and Vashishtiputra Satakarni appears in a cave at Kanheri:

"0f the queen ... of the illustrious Satakarni Vasishthiputra, descended from the race of Karddamaka kings, (and) daughter of the Mahakshatrapa Ru(dra)....... .........of the confidential minister Sateraka, a water-cistern, the meritorious gift.

— Kanheri inscription of Rudradaman I's daughter".[10]

Rudradāman also conquered the Yaudheya tribes in Haryana, as described in the Girnar inscription:[11]

"Rudradaman (...) who by force destroyed the Yaudheyas who were loath to submit, rendered proud as they were by having manifested their' title of' heroes among all Kshatriyas."

However, in the next century the warlike Yaudheyas became more powerful. The indigenous Nagas also were aggressive toward Śaka kshatrapas in the 3rd century.

Rudradāman is also known as the king who was ruling when the Greek writer Yavanesvara translated the Yavanajataka from Greek to Sanskrit, which influenced astrology in India.[9]

Notes

- Page 9, Journal of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Volume 7, Asiatic Society of Bombay, Publisher: The Society, 1867, Original from Harvard University, Digitized 14 Jun 2008

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 381. ISBN 9788131716779.

- Sircar, Dineschandra (1971). Studies in the Geography of Ancient and Medieval India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 228. ISBN 9788120806900.

- "Source". Projectsouthasia.sdstate.edu. Archived from the original on 23 February 2009. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- Thomas, F. w (1921). Epigraphia Indica Vol.16. p. 24.

- Indian Archaeology 1960-61 a Review. p. 44, item 22.

- Rapson

- Rapson, "Indian coins of the British Museum" p.lx

- "Source". Groups.mcs.st-and.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- Burgess, James; Bühler, Georg (1883). Report on the Elura cave temples and the Brahmanical and Jaina caves in western India; completing the results of the fifth, sixth, and seventh seasons' operations of the Archaeological survey, 1877-78, 1878-79, 1879-80. Supplementary to the volume on "The cave temples of India.". London, Trübner & Co. p. 78.

- Rosenfield, "The dynastic art of the Kushans", p132

References

- Todd, James - The Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan, Rajputana Publications, 1942

- Michell, George - PRINCELY RAJASTHAN - Rajput Palaces and Mansions, Oriental Books, 1992

- Rosenfield, "The dynastic art of the Kushans"

- Divatia, N. B. (1993). Gujarati Language and Literature. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0648-5.

- Buddhist critical spirituality: Prajñā and Śūnyatā, by Shōhei Ichimura, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers (2001), ISBN 81-208-1798-2