Homorganic consonant

In phonetics, a homorganic consonant (from homo- "same" and organ "(speech) organ") is a consonant sound articulated in the same place of articulation as another. For example, [p], [b] and [m] are homorganic consonants of each other as they share the place of articulation of bilabial. Consonants not articulated in the same place are called heterorganic.

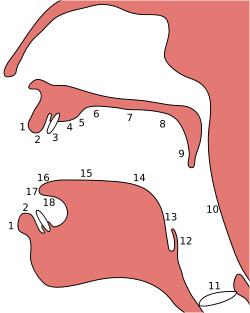

1. Exo-labial, 2. Endo-labial, 3. Dental, 4. Alveolar, 5. Post-alveolar, 6. Pre-palatal, 7. Palatal, 8. Velar, 9. Uvular, 10. Pharyngeal, 11. Glottal, 12. Epiglottal, 13. Radical, 14. Postero-dorsal, 15. Antero-dorsal, 16. Laminal, 17. Apical, 18. Sub-apical

Articulatory position

Descriptive phonetic classification relies on the relationships between a number of technical terms that describe the way sounds are made; and one of the relevant elements involves that place at which a specific sound is formed and voiced.[1] In articulatory phonetics, the specific "place of articulation" or "point of articulation" of a consonant is that point of contact, where an obstruction occurs in the vocal tract between an active (moving) articulator (typically some part of the tongue) and a passive (stationary) articulator (typically some part of the roof of the mouth). Along with the manner of articulation and phonation, this gives the consonant its distinctive sound.

Similar articulatory position

Consonants that have a similar or the same place of articulation, such as the alveolar sounds (n, t, d, s, z, l) in English, are said to be homorganic.

Homorganic nasal rule

A homorganic nasal rule is a case in which the point of articulation of the initial sound is assimilated by the last sound in a prefix. An example of this rule is found in the Yoruba language, where ba, "meet", becomes mba, "is meeting", while sun, "sleep", becomes nsun, "is sleeping".

Consonant clustering

Two or more consonant sounds may appear sequentially linked or clustered as either identical consonants or homorganic consonants that differ slightly in the manner of articulation, as when the first consonant is a fricative and the second is a stop.[2]

In some languages, a syllable-initial homorganic sequence of a stop and a nasal is quite uncontroversially treated as a sequence of two separate segments; and the separate status of the stop and the nasal is quite clear. In Russian, the stop + nasal sequences are just one of the possible types amongst many different syllable-initial consonant sequences that occur.[3] In English, nasal + stop sequences within a morpheme must be homorganic.[4]

Consonant length

In languages as diverse as Arabic, Tamil and Icelandic, there is a phonological contrast between long and short consonants,[5] which are distinguishable from consonant clusters. In phonetics, gemination happens when a spoken consonant is pronounced for an audibly longer period of time than a short consonant.

Consonant length is distinctive in some languages. In Japanese, for example, 来た (kita) means 'came; arrived', while 切った (kitta) means 'cut; sliced'. The romanization or transliteration of the sound of each Japanese word produces the misleading impression of a doubled consonant.

See also

- Manner of articulation

- Relative articulation

- List of phonetics topics

- Hepburn romanization

- Ƞ

Notes

- Laver, John. (2003)."Linguistic Phonetics," in The Handbook of Linguistics, pp. 164-178.

- Ravid, Dorit diskin et al. (2005). Perspectives on Language and Language Development, p. 55.

- Ladefoged, Peter et al. (1996). The Sounds of the World's Languages, p. 128.

- Ladefoged, p. 119.

- Ladefoged, p. 92.

References

- Aronoff, Mark and Janie Rees-Miller. (2003). The Handbook of Linguistics. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-0252-0; OCLC 185384910

- Ladefoged, Peter; Maddieson, Ian (1996). The Sounds of the World's Languages. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-19815-4.

- Ravid, Dorit Diskin, Hava Bat-Zeev Shyldkrot and Ruth Aronson Berman. (2005). Perspectives on Language and Language Development: Essays in Honor of Ruth A. Berman. Dordrecht: Springer (Kulwer Academic). ISBN 978-1-4020-7903-0; OCLC 55220212