Ober Ost

Ober Ost is short for Oberbefehlshaber der gesamten Deutschen Streitkräfte im Osten, German for "Supreme Commander of All German Forces in the East" during World War I. In practice it refers not only to said commander, but also to his governing military staff and the district they controlled: Ober Ost was in command of the German section of the Eastern Front.

Supreme Commander of All German Forces in the East Oberbefehlshaber der gesamten Deutschen Streitkräfte im Osten | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1914–1919 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Military occupation authority of the German Empire | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Königsberg (HQ, 1919) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Supreme Commander | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1914–1916 | Paul von Hindenburg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1916–1918 | Prince Leopold of Bavaria | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chief of Staff | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1914–1916 | Erich Ludendorff | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1916–1918 | Max Hoffmann | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | World War I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Established | 1914 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| March 3, 1918 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| November 11, 1918 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1919 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1916 | 108,808 km2 (42,011 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1916 | 2,909,935 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Extension

Ober Ost, set up in November 1914, initially came under the command of Paul von Hindenburg, a Prussian general who had come out of retirement to achieve the German victory of the Battle of Tannenberg in August 1914 and became a national hero. When the Chief of the General Staff Erich von Falkenhayn was dismissed from office in August 1916, Hindenburg took over at the General Staff, and Prince Leopold of Bavaria took control of the Ober Ost.

By October 1915 the Imperial German Army had advanced so far to the east that Central Poland could be put under a civil administration - accordingly, the German Empire established the Government General of Warsaw and the Austro-Hungarian Empire set up the Government General of Lublin. The military Ober Ost government from then on controlled only the conquered areas east and north of Central Poland.

After the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk of March 1918, the German Empire effectively controlled Lithuania, Latvia, Belarus, parts of Poland, and Courland, all of which had formerly formed part of the Russian Empire.[1] Ober Ost itself controlled present-day Lithuania, Latvia, Belarus, Poland, and Courland. The land area it administered was around 108,808 km2 (42,011 sq mi).

Policies

Ober Ost ruled the land with an iron fist. The movement policy or Verkehrspolitik, divided the land without regard to the existing social and ethnic organization and patterns. One was not allowed to move between the districts, which destroyed the livelihood of many merchants and prevented indigenous people from visiting friends and relatives in neighboring districts.[2] They also tried to "civilize" the people in the Ober Ost-controlled land, attempting to integrate German ideals and institutions[2] with existing cultures. They constructed railroads but only Germans were allowed to ride them and schools were taught by German instructors, since they lacked trained Lithuanians.[3]

In 1915, when large territories came under Ober Ost's administration as a result of military successes on the Eastern Front. Erich Ludendorff, von Hindenburg's second in command, set up a system of managing the large area now under its jurisdiction. Although von Hindenburg was technically in command, it was Ludendorff who had actual control of the administration. There were ten staff members, each with a specialty (finance, agriculture, etc.). The area was divided into the Courland District, the Lithuania District and the Bialystok-Grodno District, each overseen by a district commander. Ludendorff's plan was to make Ober Ost a colonial territory for the settlement of his troops after the war as well as provide a haven for German refugees from inner Russia.[3] Ludendorff quickly organized Ober Ost so that it was a self-sustaining region, growing all its own food and even exporting surpluses to Berlin. The largest resource was one that Ludendorff was unable to exploit effectively: the local population had no interest in helping obtain a German victory as they had no say in their government and were subject to increasing requisitions and taxes.[3]

Communication with locals

There were a great many problems with communication with indigenous persons within the Ober Ost. Among the upper class locals the soldiers could get by with French or German and in large villages the Jewish population would speak German or Yiddish, "which the Germans would somehow comprehend".[4] In the rural areas and amongst peasant populations soldiers had to rely on interpreters who spoke Lithuanian, Latvian, or Polish.[4] These language problems were not helped by the thinly-stretched administrations, which would sometimes number 100 men in an area as large as Rhode Island.[4] The clergy were at times relied upon to spread messages to the masses, since this was an effective way of spreading a message to people who speak a different language.[4] A young officer-administrator named Vagts related that he listened (through a translator) to a sermon by a priest who tells his congregation to stay off highways after nightfall, hand in firearms and not to have anything to do with Bolshevist agents, exactly as Vagts had told him to do earlier.[4]

Russian Revolution

Given the uncertain situation caused by the Russian October Revolution in 1917 and the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918, some indigenes elected Duke Adolf Friedrich of Mecklenburg as head of the United Baltic Duchy, and the second duke of Urach as king of Lithuania, but these plans collapsed in November 1918.

Administrative divisions

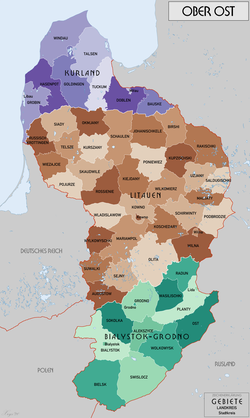

The Ober Ost was divided into three Verwaltungsgebiete (administrative territories): Kurland, Litauen, and Bialystok-Grodno. Each was, like Germany proper, subdivided into Kreise (districts); Landkreise (rural districts) and Stadtkreise (urban districts). In 1917 the following districts existed:[5]

| Bialystok-Grodno | Kurland |

|---|---|

| Alekszyce | Bauske |

| Bialystok, Stadtkreis | Doblen |

| Bialystok, Landkreis | Goldingen |

| Bielsk | Grobin |

| Grodno, Stadtkreis | Hasenpot |

| Grodno, Landkreis | Libau, Stadtkreis |

| Lida, Stadtkreis | Mitau, Landkreis |

| Ost | Talsen |

| Planty | Tuckum |

| Radun | Windau |

| Sokolka | |

| Swislocz | |

| Wasilischky | |

| Wolkowysk |

| Litauen | |

|---|---|

| Augustow | Rossienie |

| Birshi | Russisch-Krottingen |

| Johanischkele | Saldugischki |

| Kiejdany | Schaulen |

| Koschedary | Schirwinty |

| Kowno, Stadtkreis | Sejny |

| Kowno, Landkreis | Siady |

| Kupzischki | Skaudwile |

| Kurszany | Suwalki |

| Maljaty | Telsze |

| Mariampol | Uzjany |

| Okmjany | Wiezajcie |

| Olita | Wilkomierz |

| Podbrodzie | Wilna, Stadtkreis |

| Pojurze | Wilna, Landkreis |

| Poniewiez | Wladislawow |

| Rakischki | Wylkowyschki |

The total area was 108,808 km2 (42,011 sq mi), containing a population of 2,909,935 (by the end of 1916).[6]

Main military units in 1919

- the 10th Army (10. Armee or Armeeoberkommando 10), Commanding Officer Erich von Falkenhayn, Grodno

- the Army Group Mackensen (Heeresgruppe Kiew)

Aftermath

With the end of the war and collapse of the empire, the Germans started to withdraw, sometimes in a piecemeal and disorganized way, from Ober Ost around late 1918 and early 1919.[7] In the vacuum left by their retreat, conflicts arose as various former occupied nations declared independence, clashing with the various factions of the Russian Revolution and subsequent Civil War, and with each other. For details, see:

- Soviet westward offensive of 1918–19, part of the Polish–Soviet War (the largest of the resulting conflicts)

- Ukrainian–Soviet War and Polish–Ukrainian War

- Estonian War of Independence

- Latvian War of Independence

- Lithuanian Wars of Independence

Parallels with Nazi German policy

Vejas Gabriel Liulevicius postulates in his book War Land on the Eastern Front: Culture, National Identity, and German Occupation in World War I, that a line can be traced from Ober Ost's policies and assumptions to Nazi Germany's plans and attitudes towards Eastern Europe. His main argument is that "German troops developed a revulsion towards the 'East', and came to think of it as a timeless region beset by chaos, disease and barbarism", instead of what it really was, a region suffering from the ravages of warfare.[8] He claims that the encounter with the East formed an idea of 'spaces and races' that needed to be "cleared and cleansed". Although he has garnered a great deal of evidence for his thesis, including government documents, letters and diaries, in German and Lithuanian, there are still problems with his work. For example, he does not say much about the reception of German policies by native populations.[8] Also, he "makes almost no attempt to relate wartime occupation policies and practice in Ober Ost to those in Germany's colonial territories overseas".[8]

See also

References

- Figes 1998, pp. xxiii, 548.

- Gettman, Erin (June 2002). "The Baltic Region during WWI". Retrieved 2008-03-02.

- Koehl, Robert Lewis (October 1953). "A Prelude to Hitler's Greater Germany". The American Historical Review. 59 (1): 43–65. doi:10.2307/1844652. JSTOR 1844652.

- Vagts, Alfred (Spring 1943). "A memoir of Military Occupation". Military Affairs. 7 (1): 16–24. doi:10.2307/1982990. JSTOR 1982990.

- "Kreise im Generalgouvernement Warschau 1917". territorial.de. Retrieved 2019-12-21.

- "Ober Ost ( Kurland , Litauen , Bialystok-Grodno) 1917". www.brest-litowsk.libau-kurland-baltikum.de. Retrieved 2019-12-21.

- Böhler, Jochen (2019). Civil War in Central Europe, 1918-1921: The Reconstruction of Poland. Oxford University Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-19-879448-6.

- Gatrell, Peter; Liulevicius, Vejas Gabriel (2001). "Review of War Land on the Eastern Front: Culture, National Identity, and German Occupation in World War I". Slavic Review. 60 (4): 844–845. doi:10.2307/2697514. JSTOR 2697514.

Further reading

- Davies, Norman (2003) [1972]. White Eagle, Red Star: The Polish–Soviet War, 1919–20 (2nd ed.). London: Random House. ISBN 0-7126-0694-7.

- Figes, Orlando (1998). A People's Tragedy: the Russian Revolution, 1891–1924. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-670-85916-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schwonek, M. R. (January 2001). "Book Reviews: War Land on the Eastern Front: Culture, National Identity, and German Occupation in World War I by Vejas, Gabriel Liulevicius". The Journal of Military History. Lexington, Virginia: Virginia Military Institute and the George C. Marshall Foundation. 65 (1): 212–213. ISSN 0899-3718. JSTOR 2677470.

- Stone, Norman (1975). The Eastern Front, 1914–1917. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-0-68414-492-4.

.svg.png)