Ivo Andrić

Ivo Andrić (Serbian Cyrillic: Иво Андрић, pronounced [ǐːʋo ǎːndritɕ]; born Ivan Andrić; 9 October 1892 – 13 March 1975) was a Yugoslav[lower-alpha 1] novelist, poet and short story writer who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1961. His writings dealt mainly with life in his native Bosnia under Ottoman rule.

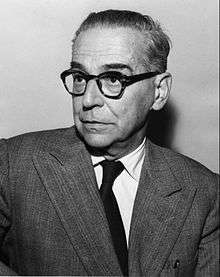

Ivo Andrić | |

|---|---|

Ivo Andrić, 1961 | |

| Born | Ivan Andrić 9 October 1892 Dolac, Travnik, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 13 March 1975 (aged 82) Belgrade, Serbia, Yugoslavia |

| Resting place | Belgrade New Cemetery, Republic of Serbia |

| Occupation | Writer, diplomat, politician |

| Language | Serbo-Croatian |

| Nationality | Yugoslav |

| Alma mater | University of Zagreb University of Vienna Jagiellonian University University of Graz |

| Notable work | The Bridge on the Drina (1945) (among other works) |

| Notable awards | |

| Years active | 1911–1974 |

| Spouse | Milica Babić

( m. 1958; died 1968) |

| Signature |  |

| Website | |

| ivoandric | |

Born in Travnik in the Austrian Empire, modern-day Bosnia, Andrić attended high school in Sarajevo, where he became an active member of several South Slav national youth organizations. Following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in June 1914, Andrić was arrested and imprisoned by the Austro-Hungarian police, who suspected his involvement in the plot. As the authorities were unable to build a strong case against him, he spent much of the war under house arrest, only being released following a general amnesty for such cases in July 1917. After the war, he studied South Slavic history and literature at universities in Zagreb and Graz, eventually attaining his Ph.D. in Graz in 1924. He worked in the diplomatic service of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia from 1920 to 1923 and again from 1924 to 1941. In 1939, he became Yugoslavia's ambassador to Germany, but his tenure ended in April 1941 with the German-led invasion of his country. Shortly after the invasion, Andrić returned to German-occupied Belgrade. He lived quietly in a friend's apartment for the duration of World War II, in conditions likened by some biographers to house arrest, and wrote some of his most important works, including Na Drini ćuprija (The Bridge on the Drina).

Following the war, Andrić was named to a number of ceremonial posts in Yugoslavia, which had since come under communist rule. In 1961, the Nobel Committee awarded him the Nobel Prize in Literature, selecting him over writers such as J. R. R. Tolkien, Robert Frost, John Steinbeck and E. M. Forster. The Committee cited "the epic force with which he ... traced themes and depicted human destinies drawn from his country's history". Afterwards, Andrić's works found an international audience and were translated into a number of languages. In subsequent years, he received a number of awards in his native country. Andrić's health declined substantially in late 1974 and he died in Belgrade the following March.

In the years following Andrić's death, the Belgrade apartment where he spent much of World War II was converted into a museum and a nearby street corner was named in his honour. A number of other cities in the former Yugoslavia also have streets bearing his name. In 2012, filmmaker Emir Kusturica began construction of an ethno-town in eastern Bosnia that is named after Andrić. As Yugoslavia's only Nobel Prize-winning writer, Andrić was well known and respected in his native country during his lifetime. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, beginning in the 1950s and continuing past the breakup of Yugoslavia, his works have been disparaged by Bosniak literary critics for their supposed anti-Muslim bias. In Croatia, his works were long shunned for nationalist reasons, and even briefly blacklisted following Yugoslavia's dissolution, but were rehabilitated by the literary community at the start of the 21st century. He is highly regarded in Serbia for his contributions to Serbian literature.

Early life

Family

Ivan Andrić[lower-alpha 2] was born in the village of Dolac, near Travnik,[6] on 9 October 1892, while his mother, Katarina (née Pejić), was in the town visiting relatives.[5] Andrić's parents were both Catholic Croats.[7] He was his parents' only child.[8] His father, Antun, was a struggling silversmith who resorted to working as a school janitor in Sarajevo,[9] where he lived with his wife and infant son.[8] At the age of 32, Antun died of tuberculosis, like most of his siblings.[5] Andrić was only two years old at the time.[5] Widowed and penniless, Andrić's mother took him to Višegrad and placed him in the care of her sister-in-law Ana and brother-in-law Ivan Matković, a police officer.[8] The couple were financially stable but childless, so they agreed to look after the infant and brought him up as their own.[9] Meanwhile, Andrić's mother returned to Sarajevo seeking employment.[10]

Andrić was raised in a country that had changed little since the Ottoman period despite being mandated to Austria-Hungary at the Congress of Berlin in 1878.[10] Eastern and Western culture intermingled in Bosnia to a far greater extent than anywhere else in the Balkan peninsula.[11] Having lived there from an early age, Andrić came to cherish Višegrad, calling it "my real home".[9] Though it was a small provincial town (or kasaba), Višegrad proved to be an enduring source of inspiration.[10] It was a multi-ethnic and multi-confessional town, the predominant groups being Serbs (Orthodox Christians) and Bosnian Muslims (Bosniaks).[12] From an early age, Andrić closely observed the customs of the local people.[10] These customs, and the particularities of life in eastern Bosnia, would later be detailed in his works.[13] Andrić made his first friends in Višegrad, playing with them along the Drina River and the town's famous Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge.[14]

Primary and secondary education

At age six, Andrić began primary school.[14] He later recounted that these were the happiest days of his life.[10] At the age of ten, he received a three-year scholarship from a Croat cultural group called Napredak (Progress) to study in Sarajevo.[13] In the autumn of 1902,[14] he was registered at the Great Sarajevo Gymnasium (Serbo-Croatian: Velika Sarajevska gimnazija),[13] the oldest secondary school in Bosnia.[14] While in Sarajevo, Andrić lived with his mother, who worked in a rug factory.[13] At the time, the city was overflowing with civil servants from all parts of Austria-Hungary, and thus many languages could be heard in its restaurants, cafés and on its streets. Culturally, the city boasted a strong Germanic element, and the curriculum in educational institutions was designed to reflect this. From a total of 83 teachers that worked at Andrić's school over a twenty-year period, only three were natives of Bosnia and Herzegovina. "The teaching program," biographer Celia Hawkesworth notes, "was devoted to producing dedicated supporters of the [Habsburg] Monarchy". Andrić disapproved. "All that came ... at secondary school and university," he wrote, "was rough, crude, automatic, without concern, faith, humanity, warmth or love."[14]

Andrić experienced difficulty in his studies, finding mathematics particularly challenging, and had to repeat the sixth grade. For a time, he lost his scholarship due to poor grades.[13] Hawkesworth attributes Andrić's initial lack of academic success at least partly to his alienation from most of his teachers.[15] Nonetheless, he excelled in languages, particularly Latin, Greek and German. Although he initially showed substantial interest in natural sciences, he later began focusing on literature, likely under the influence of his two Croat instructors, writer and politician Đuro Šurmin and poet Tugomir Alaupović. Of all his teachers in Sarajevo, Andrić liked Alaupović best, and the two became lifelong friends.[13]

Andrić felt he was destined to become a writer. He began writing in secondary school, but received little encouragement from his mother. He recalled that when he showed her one of his first works, she replied: "Did you write this? What did you do that for?"[15] Andrić published his first two poems in 1911 in a journal called Bosanska vila (Bosnian Fairy), which promoted Serbo-Croat unity. At the time, he was still a secondary school student. Prior to World War I, his poems, essays, reviews, and translations appeared in journals such as Vihor (Whirlwind), Savremenik (The Contemporary), Hrvatski pokret (The Croatian Movement), and Književne novine (Literary News). One of Andrić's favorite literary forms was lyrical reflective prose, and many of his essays and shorter pieces are prose poems. The historian Wayne S. Vucinich describes Andrić's poetry from this period as "subjective and mostly melancholic". Andrić's translations of August Strindberg, Walt Whitman, and a number of Slovene authors also appeared around this time.[16]

Student activism

~ Andrić's view of pre-war Sarajevo.[17]

In 1908, Austria-Hungary officially annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina, to the chagrin of South Slav nationalists like Andrić.[18] In late 1911, Andrić was elected the first president of the Serbo-Croat Progressive Movement (Serbo-Croatian Latin: Srpsko-Hrvatska Napredna Organizacija; SHNO),[lower-alpha 3] a Sarajevo-based secret society that promoted unity and friendship between Serb and Croat youth and opposed the Austro-Hungarian occupation. Its members were vehemently criticized by both Serb and Croat nationalists, who dismissed them as "traitors to their nations".[20] Unfazed, Andrić continued agitating against the Austro-Hungarians. On 28 February 1912, he spoke before a crowd of 100 student protesters at Sarajevo's railway station, urging them to continue their demonstrations. The Austro-Hungarian police later began harassing and prosecuting SHNO members. Ten were expelled from their schools or penalized in some other way, though Andrić himself escaped punishment.[21] Andrić also joined the South Slav student movement known as Young Bosnia, becoming one of its most prominent members.[22][23]

In 1912, Andrić registered at the University of Zagreb, having received a scholarship from an educational foundation in Sarajevo.[15] He enrolled in the department of mathematics and natural sciences because these were the only fields for which scholarships were offered, but was able to take some courses in Croatian literature. Andrić was well received by South Slav nationalists there, and regularly participated in on-campus demonstrations. This led to his being reprimanded by the university. In 1913, after completing two semesters in Zagreb, Andrić transferred to the University of Vienna, where he resumed his studies. While in Vienna, he joined South Slav students in promoting the cause of Yugoslav unity and worked closely with two Yugoslav student societies, the Serbian cultural society Zora (Dawn) and the Croatian student club Zvonimir, which shared his views on "integral Yugoslavism" (the eventual assimilation of all South Slav cultures into one).[16]

Despite finding like-minded students in Vienna, the city's climate took a toll on Andrić's health.[24] He contracted tuberculosis and became seriously ill, then asked to leave Vienna on medical grounds and continue his studies elsewhere, though Hawkesworth believes he may actually have been taking part in a protest of South Slav students that were boycotting German-speaking universities and transferring to Slavic ones.[15] For a time, Andrić had considered transferring to a school in Russia but ultimately decided to complete his fourth semester at Jagiellonian University in Kraków.[24] He transferred in early 1914.[15] Andrić started his literary career as a poet. In 1914, he was one of the contributors to Hrvatska mlada lirika (Croatian Youth Lyrics) and continued to publish translations, poems and reviews.[24]

World War I

On 28 June 1914, Andrić learned of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo.[25] The assassin was Gavrilo Princip, a Young Bosnian and close friend of Andrić who had been one of the first to join the SHNO in 1911.[20][lower-alpha 4] Upon hearing the news, Andrić decided to leave Kraków and return to Bosnia. He travelled by train to Zagreb, and in mid-July, departed for the coastal city of Split with his friend, the poet and fellow South Slav nationalist Vladimir Čerina.[24] Andrić and Čerina spent the rest of July at the latter's summer home. As the month progressed, the two became increasingly uneasy about the escalating political crisis that followed the Archduke's assassination and eventually led to the outbreak of World War I. They then went to Rijeka, where Čerina left Andrić without explanation, only saying he urgently needed to go to Italy. Several days later, Andrić learned that Čerina was being sought by the police.[25]

By the time war was declared, Andrić had returned to Split feeling exhausted and ill. Given that most of his friends had already been arrested for nationalist activities, he was certain the same fate would befall him.[25] Despite not being involved in the assassination plot,[27] in late July or early August,[lower-alpha 5] Andrić was arrested for "anti-state activities", and imprisoned in Split.[24] He was subsequently transferred to a prison in Šibenik, then to Rijeka and finally to Maribor, where he arrived on 19 August.[28] Plagued by tuberculosis, Andrić passed the time reading, talking to his cellmates and learning languages.[24]

By the following year, the case against Andrić was dropped due to lack of evidence, and he was released from prison on 20 March 1915.[28] The authorities exiled him to the village of Ovčarevo, near Travnik. He arrived there on 22 March and was placed under the supervision of local Franciscan friars. Andrić soon befriended the friar Alojzije Perčinlić and began researching the history of Bosnia's Catholic and Orthodox Christian communities under Ottoman rule.[24] Andrić lived in the parish headquarters, and the Franciscans gave him access to the monastery chronicles. In return, he assisted the parish priest and taught religious songs to pupils at the monastery school. Andrić's mother soon came to visit him and offered to serve as the parish priest's housekeeper.[29] "Mother is very happy," Andrić wrote. "It has been three whole years since she saw me. And she can't grasp all that has happened to me in that time, nor the whole of my crazy, cursed existence. She cries, kisses me and laughs in turn. Like a mother."[28]

Andrić was later transferred to a prison in Zenica, where Perčinlić regularly visited him. The Austro-Hungarian Army declared Andrić a political threat in March 1917 and exempted him from armed service. He was thus registered with a non-combat unit until February of the following year. On 2 July 1917, Emperor Charles declared a general amnesty for all of Austria-Hungary's political prisoners.[29] His freedom of movement restored, Andrić visited Višegrad and reunited with several of his school friends. He remained in Višegrad until late July, when he was mobilized. Because of his poor health, Andrić was admitted to a Sarajevo hospital and thus avoided service. He was then transferred to the Reservospital in Zenica, where he received treatment for several months before continuing to Zagreb.[29] There, Andrić again fell seriously ill and sought treatment at the Sisters of Mercy hospital, which had become a gathering place for dissidents and former political prisoners.[30]

In January 1918, Andrić joined several South Slav nationalists in editing a short-lived pan-Yugoslav periodical called Književni jug (Literary South).[29] Here and in other periodicals, Andrić published book reviews, plays, verse, and translations. Over the course of several months in early 1918, Andrić's health began to deteriorate, and his friends believed he was nearing death.[30] However, he recovered and spent the spring of 1918 in Krapina writing Ex ponto, a book of prose poetry that was published in July.[29] It was his first book.[31]

Interwar period

The end of World War I saw the disintegration of Austria-Hungary, which was replaced by a newly established South Slav state, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (renamed Yugoslavia in 1929).[30] In late 1918, Andrić re-enrolled at the University of Zagreb and resumed his studies.[29] By January 1919, he fell ill again and was back in the hospital. Fellow writer Ivo Vojnović became worried for his friend's life and appealed to Andrić's old schoolteacher Tugomir Alaupović (who had just been appointed the new kingdom's Minister of Religious Affairs) to use his connections and help Andrić pay for treatment abroad.[31] In February, Andrić wrote Alaupović and asked for help finding a government job in Belgrade. Eventually, Andrić chose to seek treatment in Split, where he stayed for the following six months.[32] During his time on the Mediterranean coast, Andrić completed a second volume of prose poetry, titled Nemiri (Unrest),[lower-alpha 6] which was published the following year. By the time Andrić left, he had almost fully recovered, and quipped that he was cured by the "air, sun and figs."[31] Troubled by news that his uncle was seriously ill, Andrić left Split in August and went to him in Višegrad. He returned to Zagreb two weeks later.[32]

Early diplomatic career

In the immediate aftermath of the war, Andrić's tendency to identify with Serbdom became increasingly apparent. In a correspondence dated December 1918, Vojnović described the young writer as "a Catholic ... a Serb from Bosnia."[31][33] By 1919, Andrić had acquired his undergraduate degree in South Slavic history and literature at the University of Zagreb.[32] He was perennially impoverished, and earned a meagre sum through his writing and editorial work. By mid-1919, he realized that he would be unable to financially support himself and his aging mother, aunt and uncle for much longer, and his appeals to Alaupović for help securing a government job became more frequent. In September 1919, Alaupović offered him a secretarial position at the Ministry of Religion, which Andrić accepted.[32]

In late October, Andrić left for Belgrade.[34] He became involved in the city's literary circles and soon acquired the distinction of being one of Belgrade's most popular young writers. Though the Belgrade press wrote positively of him, Andrić disliked being a public figure, and went into seclusion and distanced himself from his fellow writers.[35] At the same time, he grew dissatisfied with his government job and wrote to Alaupović asking for a transfer to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. On 20 February, Andrić's request was granted and he was assigned to the Foreign Ministry's mission at the Vatican.[32]

Andrić left Belgrade soon after, and reported for duty in late February. At this time, he published his first short story, Put Alije Đerzeleza (The Journey of Alija Đerzelez).[36] He complained that the consulate was understaffed and that he did not have enough time to write. All evidence suggests he had a strong distaste for the ceremony and pomp that accompanied his work in the diplomatic service, but according to Hawkesworth, he endured it with "dignified good grace".[35] Around this time, he began writing in the Ekavian dialect used in Serbia, and ceased writing in the Ijekavian dialect used in his native Bosnia.[37] Andrić soon requested another assignment, and in November, he was transferred to Bucharest.[36] Once again, his health deteriorated.[38] Nevertheless, Andrić found his consular duties there did not require much effort, so he focused on writing, contributed articles to a Romanian journal and even had time to visit his family in Bosnia. In 1922, Andrić requested another reassignment. He was transferred to the consulate in Trieste, where he arrived on 9 December.[36] The city's damp climate only caused Andrić's health to deteriorate further, and on his doctor's advice, he transferred to Graz in January 1923.[39] He arrived in the city on 23 January, and was appointed vice-consul.[36] Andrić soon enrolled at the University of Graz, resumed his schooling and began working on his doctoral dissertation in Slavic studies.[39]

Advancement

In August 1923, Andrić experienced an unexpected career setback. A law had been passed stipulating that all civil servants had to have a doctoral degree. As Andrić had not completed his dissertation, he was informed that his employment would be terminated. Andrić's well-connected friends intervened on his behalf and appealed to Foreign Minister Momčilo Ninčić, citing Andrić's diplomatic and linguistic abilities. In February 1924, the Foreign Ministry decided to retain Andrić as a day worker with the salary of a vice-consul. This gave him the opportunity to complete his Ph.D. Three months later, on 24 May, Andrić submitted his dissertation to a committee of examiners at the University of Graz, who gave it their approval.[36] This allowed Andrić to take the examinations necessary for his Ph.D to be confirmed. He passed both his exams, and on 13 July, received his Ph.D. The committee of examiners recommended that Andrić's dissertation be published. Andrić chose the title Die Entwicklung des geistigen Lebens in Bosnien unter der Einwirkung der türkischen Herrschaft (The Development of Spiritual Life in Bosnia Under the Influence of Turkish Rule).[40] In it, he characterized the Ottoman occupation as a yoke that still loomed over Bosnia.[41] "The effect of Turkish rule was absolutely negative," he wrote. "The Turks could bring no cultural content or sense of higher mission, even to those South Slavs who accepted Islam."[42]

Several days after receiving his Ph.D, Andrić wrote the Foreign Minister asking to be reinstated and submitted a copy of his dissertation, university documents and a medical certification that deemed him to be in good health. In September, the Foreign Ministry granted his request. Andrić stayed in Graz until 31 October, when he was assigned to the Foreign Ministry's Belgrade headquarters. During the two years he was in Belgrade, Andrić spent much of his time writing.[40] His first collection of short stories was published in 1924, and he received a prize from the Serbian Royal Academy (of which he became a full-fledged member in February 1926). In October 1926, he was assigned to the consulate in Marseille and again appointed vice-consul.[43] On 9 December 1926, he was transferred to the Yugoslav embassy in Paris.[40] Andrić's time in France was marked by increasing loneliness and isolation. His uncle had died in 1924, his mother the following year, and upon arriving in France, he was informed that his aunt had died as well. "Apart from official contacts," he wrote Alaupović, "I have no company whatever."[43] Andrić spent much of his time in the Paris archives poring over the reports of the French consulate in Travnik between 1809 and 1814, material he would use in Travnička hronika (Travnik Chronicle),[lower-alpha 7] one of his future novels.[40]

In April 1928, Andrić was posted to Madrid as vice-consul. While there, he wrote essays on Simón Bolívar and Francisco Goya, and began work on the novel Prokleta avlija (The Damned Yard). In June 1929, he was named secretary of the Yugoslav legation to Belgium and Luxembourg in Brussels.[40] On 1 January 1930, he was sent to Switzerland as part of Yugoslavia's permanent delegation to the League of Nations in Geneva, and was named deputy delegate the following year. In 1933, Andrić returned to Belgrade; two years later, he was named head of the political department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. On 5 November 1937, Andrić became assistant to Milan Stojadinović, Yugoslavia's Prime Minister and Foreign Minister.[43] That year, France decorated him with the Order of the Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour.[47]

World War II

~ An excerpt from Andrić's only journal entry of 1940.[48]

Andrić was appointed Yugoslavia's ambassador to Germany in late March or early April 1939.[lower-alpha 8] This appointment, Hawkesworth writes, shows that he was highly regarded by his country's leadership.[35] Yugoslavia's King Alexander had been assassinated in Marseille in 1934. He was succeeded by his ten-year-old son Peter, and a regency council led by Peter's uncle Paul was established to rule in his place until he turned 18. Paul's government established closer economic and political ties with Germany. In March 1941, Yugoslavia signed the Tripartite Pact, pledging support for Germany and Italy.[49] Though the negotiations had occurred behind Andrić's back, in his capacity as ambassador he was obliged to attend the document's signing in Berlin.[50] Andrić had previously been instructed to delay agreeing to the Axis powers' demands for as long as possible.[51] He was highly critical of the move, and on 17 March, wrote to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs asking to be relieved of his duties. Ten days later, a group of pro-Western Royal Yugoslav Air Force officers overthrew the regency and proclaimed Peter of age. This led to a breakdown in relations with Germany and prompted Adolf Hitler to order Yugoslavia's invasion.[49] Given these circumstances, Andrić's position was an extremely difficult one.[48] Nevertheless, he used the little influence he had and attempted unsuccessfully to assist Polish prisoners following the German invasion of Poland in September 1939.[49]

Prior to their invasion of his country, the Germans had offered Andrić the opportunity to evacuate to neutral Switzerland. He declined on the basis that his staff would not be allowed to go with him.[44] On 6 April 1941, the Germans and their allies invaded Yugoslavia. The country capitulated on 17 April and was subsequently partitioned between the Axis powers.[49] In early June, Andrić and his staff were taken back to German-occupied Belgrade, where some were jailed.[44] Andrić was retired from the diplomatic service, but refused to receive his pension or cooperate in any way with the puppet government that the Germans had installed in Serbia.[52][53] He was spared jail, but the Germans kept him under close surveillance throughout the occupation.[44] Because of his Croat heritage, they had offered him the chance to settle in Zagreb, then the capital of the fascist puppet state known as the Independent State of Croatia, but he declined.[54] Andrić spent the following three years in a friend's Belgrade apartment in conditions that some biographers liken to house arrest.[55] In August 1941, the puppet authorities in German-occupied Serbia issued the Appeal to the Serbian Nation, calling upon the country's inhabitants to abstain from the communist-led rebellion against the Germans; Andrić refused to sign.[53][56] He directed most of his energies towards writing, and during this time completed two of his best known novels, Na Drini ćuprija (The Bridge on the Drina) and Travnička hronika.[57]

In mid-1942, Andrić sent a message of sympathy to Draža Mihailović, the leader of the royalist Chetniks, one of two resistance movements vying for power in Axis-occupied Yugoslavia, the other being Josip Broz Tito's communist Partisans.[54][lower-alpha 9] In 1944, Andrić was forced to leave his friend's apartment during the Allied bombing of Belgrade and evacuate the city. As he joined a column of refugees, he became ashamed that he was fleeing by himself, in contrast to the masses of people accompanied by their children, spouses and infirm parents. "I looked myself up and down," he wrote, "and saw I was saving only myself and my overcoat." In the ensuing months, Andrić refused to leave the apartment, even during the heaviest bombing. That October, the Red Army and the Partisans drove the Germans out of Belgrade, and Tito proclaimed himself Yugoslavia's ruler.[52]

Later life

Political career and marriage

Andrić initially had a precarious relationship with the communists because he had previously been an official in the royalist government.[59][lower-alpha 10] He returned to public life only once the Germans had been forced out of Belgrade.[44] Na Drini ćuprija was published in March 1945. It was followed by Travnička hronika that September and Gospođica (The Young Lady)[lower-alpha 11] that November. Na Drini ćuprija came to be regarded as Andrić's magnum opus and was proclaimed a classic of Yugoslav literature by the communists.[57] It chronicles the history of the Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge and the town of Višegrad from the bridge's construction in the 16th century until the outbreak of World War I. The second novel, Travnička hronika, follows a French diplomat in Bosnia during the Napoleonic Wars. The third, Gospođica, revolves around the life of a Sarajevan woman.[44] In the post-war period, Andrić also published several short story collections, some travel memoirs, and a number of essays on writers such as Vuk Karadžić, Petar II Petrović-Njegoš, and Petar Kočić.[61]

In November 1946, Andrić was elected vice-president of the Society for the Cultural Cooperation of Yugoslavia with the Soviet Union. The same month, he was named president of the Yugoslav Writers' Union.[45] The following year, he became a member of the People's Assembly of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[45] In 1948, Andrić published a collection of short stories he had written during the war.[44] His work came to influence writers such as Branko Ćopić, Vladan Desnica, Mihailo Lalić and Meša Selimović.[44] In April 1950, Andrić became a deputy in the National Assembly of Yugoslavia. He was decorated by the Presidium of the National Assembly for his services to the Yugoslav people in 1952.[45] In 1953, his career as a parliamentary deputy came to an end.[62] The following year, Andrić published the novella Prokleta avlija (The Damned Yard), which tells of life in an Ottoman prison in Istanbul.[62] That December, he was admitted into the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, the country's ruling party. According to Hawkesworth, it is unlikely he joined the party out of ideological conviction, but rather to "serve his country as fully as possible".[45]

On 27 September 1958, the 66-year-old Andrić married Milica Babić, a costume designer at the National Theatre of Serbia who was almost twenty years his junior.[62] Earlier, he had announced it was "probably better" that a writer never marry. "He was perpetually persecuted by a kind of fear," a close friend recalled. "It seemed as though he had been born afraid, and that is why he married so late. He simply did not dare enter that area of life."[63]

Nobel Prize, international recognition and death

By the late 1950s, Andrić's works had been translated into a number of languages. On 26 October 1961, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature by the Swedish Academy.[63] Documents released 50 years later revealed that the Nobel Committee had selected Andrić over writers such as J.R.R. Tolkien, Robert Frost, John Steinbeck and E.M. Forster.[64][65] The Committee cited "the epic force with which he has traced themes and depicted human destinies drawn from his country's history".[4] Once the news was announced, Andrić's Belgrade apartment was swarmed by reporters, and he publicly thanked the Nobel Committee for selecting him as the winner of that year's prize.[63] Andrić donated the entirety of his prize money, which amounted to some 30 million dinars, and prescribed that it be used to purchase library books in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[66]

The Nobel Prize ensured Andrić received global recognition. The following March, he fell ill while on a trip to Cairo and had to return to Belgrade for an operation. He was obliged to cancel all promotional events in Europe and North America, but his works continued to be reprinted and translated into numerous languages. Judging by letters he wrote at the time, Andrić felt burdened by the attention but did his best not to show it publicly.[67] Upon receiving the Nobel Prize, the number of awards and honours bestowed upon him multiplied. He received the Order of the Republic in 1962, as well as 27 July Award of Bosnia-Herzegovina, the AVNOJ Award in 1967, and the Order of the Hero of Socialist Labour in 1972.[68] In addition to being a member of the Yugoslav and Serbian academies of sciences and arts, he also became a correspondent of their Bosnian and Slovenian counterparts, and received honorary doctorates from the universities of Belgrade, Sarajevo and Kraków.[62]

Andrić's wife died on 16 March 1968. His health deteriorated steadily and he travelled little in his final years. He continued to write until 1974, when his health took another turn for the worse. In December 1974, he was admitted to a Belgrade hospital.[67] He soon fell into a coma, and died in the Military Medical Academy at 1:15 a.m. on 13 March 1975, aged 82. His remains were cremated, and on 24 April, the urn containing his ashes was buried at the Alley of Distinguished Citizens in Belgrade's New Cemetery.[69] The ceremony was attended by about 10,000 residents of Belgrade.[67][69]

Influences, style and themes

Andrić was an avid reader in his youth. The young Andrić's literary interests varied greatly, ranging from the Greek and Latin Classics to the works of past and contemporary literary figures, including German and Austrian writers such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Heinrich Heine, Friedrich Nietzsche, Franz Kafka, Rainer Maria Rilke and Thomas Mann, the French writers Michel de Montaigne, Blaise Pascal, Gustave Flaubert, Victor Hugo and Guy de Maupassant, and the British writers Thomas Carlyle, Walter Scott and Joseph Conrad. Andrić also read the works of the Spanish writer Miguel de Cervantes, the Italian poet and philosopher Giacomo Leopardi, the Russian writer Nikolay Chernyshevsky, the Norwegian writer Henrik Ibsen, the American writers Walt Whitman and Henry James, and the Czechoslovak philosopher Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk.[13] Andrić was especially fond of Polish literature, and later stated that it had greatly influenced him. He held several Serb writers in high esteem, particularly Karadžić, Njegoš, Kočić and Aleksa Šantić.[13] Andrić also admired the Slovene poets Fran Levstik, Josip Murn and Oton Župančič, and translated some of their works.[70] Kafka appears to have had a significant influence on Andrić's prose, and his philosophical outlook was informed strongly by the works of Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard. At one point in his youth, Andrić even took an interest in Chinese and Japanese literature.[71]

Much of Andrić's work was inspired by the traditions and peculiarities of life in Bosnia, and examines the complexity and cultural contrasts of the region's Muslim, Serb and Croat inhabitants. His two best known novels, Na Drini ćuprija and Travnička hronika, subtly contrast Ottoman Bosnia's "oriental" propensities to the "Western atmosphere" first introduced by the French and later the Austro-Hungarians.[61] His works contain many words of Turkish, Arabic or Persian origin that found their way into the languages of the South Slavs during Ottoman rule. According to Vucinich, Andrić uses these words to "express oriental nuances and subtleties that cannot be rendered as well in his own Serbo-Croatian".[13]

In the opinion of literary historian Nicholas Moravcevich, Andrić's work "frequently betrays his profound sadness over the misery and waste inherent in the passing of time".[61] Na Drini ćuprija remains his most famous novel and has received the most scholarly analysis of all his works. Most scholars have interpreted the eponymous bridge as a metonym for Yugoslavia, which was itself a bridge between East and West during the Cold War.[72] In his Nobel acceptance speech, Andrić described the country as one "which, at break-neck speed and at the cost of great sacrifices and prodigious efforts, is trying in all fields, including the field of culture, to make up for those things of which it has been deprived by a singularly turbulent and hostile past."[73] In Andrić's view, the seemingly conflicting positions of Yugoslavia's disparate ethnic groups could be overcome by knowing one's history. This, he surmised, would help future generations avoid the mistakes of the past, and was in line with his cyclical view of time. Andrić expressed hope that these differences could be bridged and "histories demystified".[74]

Legacy

Shortly before his death, Andrić stated that he wished for all his possessions to be preserved as part of an endowment to be used for "general cultural and humanitarian purposes". In March 1976, an administrative committee decided that the purpose of the endowment would be to promote the study of Andrić's work, as well as art and literature in general. The Ivo Andrić Endowment has since organized a number of international conferences, made grants to foreign scholars studying the writer's works and offered financial aid to cover the publication costs of books relating to Andrić. An annual yearbook, titled Sveske Zadužbine Ive Andrića (The Journals of the Ivo Andrić Endowment), is published by the organization. Andrić's will and testament stipulated that an award be given annually to the author of each subsequent year's best collection of short stories.[68] The street that runs beside Belgrade's New Palace, now the seat of the President of Serbia, was posthumously named Andrićev venac (Andrić's Crescent) in his honour. It includes a life-sized statue of the writer. The flat in which Andrić spent his final years has been turned into a museum.[75] Opened over a year after Andrić's death, it houses books, manuscripts, documents, photographs and personal belongings.[68] Several of Serbia's other major cities, such as Novi Sad and Kragujevac, have streets named after Andrić.[76] Streets in a number of cities in Bosnia and Herzegovina, such as Sarajevo, Banja Luka, Tuzla, and Višegrad, also carry his name.[77]

Andrić remains the only writer from the former Yugoslavia to have been awarded the Nobel Prize.[61] Given his use of the Ekavian dialect, and the fact that most of his novels and short stories were written in Belgrade, his works have become associated almost exclusively with Serbian literature.[78] The Slavonic studies professor Bojan Aleksov characterizes Andrić as one of Serbian literature's two central pillars, the other being Njegoš.[79] "The plasticity of his narrative," Moravcevich writes, "the depth of his psychological insight, and the universality of his symbolism remain unsurpassed in all of Serbian literature."[61] Due to his self-identification as a Serb, many in the Bosniak and Croat literary establishments have come to "reject or limit Andrić's association with their literatures".[78] Following Yugoslavia's disintegration in the early 1990s, Andrić's works were blacklisted in Croatia under President Franjo Tuđman.[80][81] The Croatian historian and politician Ivo Banac characterizes Andrić as a writer who "missed the Chetnik train by a very small margin".[82] Though Andrić remains a controversial figure in Croatia, the Croatian literary establishment largely rehabilitated his works following Tuđman's death in 1999.[83]

Bosniak scholars have objected to the ostensibly negative portrayal of Muslim characters in Andrić's works.[84] During the 1950s, his most vocal Bosniak detractors accused him of being a plagiarist, homosexual and Serbian nationalist. Some went so far as to call for his Nobel Prize to be taken away. Most Bosniak criticism of his works appeared in the period immediately prior to the breakup of Yugoslavia and in the aftermath of the Bosnian War.[85] In early 1992, a Bosniak nationalist in Višegrad destroyed a statue of Andrić with a sledgehammer.[86] In 2009, Nezim Halilović, the imam of Sarajevo's King Fahd Mosque, derided Andrić as a "Chetnik ideologue" during a sermon.[87] In 2012, the filmmaker Emir Kusturica and Bosnian Serb President Milorad Dodik unveiled another statue of Andrić in Višegrad, this time as part of the construction of an ethno-town[lower-alpha 12] called Andrićgrad, sponsored by Kusturica and the Government of Republika Srpska.[89] Andrićgrad was officially inaugurated in June 2014, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the assassination of Franz Ferdinand.[90]

Bibliography

Source: The Swedish Academy (2007, Bibliography)

- 1918 Ex Ponto. Književni jug, Zagreb (poems)

- 1920 Nemiri. Sv. Kugli, Zagreb (poems)

- 1920 Put Alije Đerzeleza. S. B. Cvijanović, Belgrade (novella)

- 1924 Pripovetke I. Srpska književna zadruga, Belgrade (short story collection)

- 1931 Pripovetke. Srpska književna zadruga, Belgrade (short story collection)

- 1936 Pripovetke II. Srpska književna zadruga, Belgrade (short story collection)

- 1945 Izabrane pripovetke. Svjetlost, Sarajevo (short story collection)

- 1945 Na Drini ćuprija. Prosveta, Belgrade (novel)

- 1945 Travnička hronika. Državni izdavački zavod Jugoslavije, Belgrade (novel)

- 1945 Gospođica. Svjetlost, Belgrade (novella)

- 1947 Most na Žepi: Pripovetke. Prosveta, Belgrade (short story collection)

- 1947 Pripovijetke. Matica Hrvatska, Zagreb (short story collection)

- 1948 Nove pripovetke. Kultura, Belgrade (short story collection)

- 1948 Priča o vezirovom slonu. Nakladni zavod Hrvatske, Zagreb (novella)

- 1949 Priča o kmetu Simanu. Novo pokoljenje, Zagreb (short story)

- 1952 Pod gradićem: Pripovetke o životu bosanskog sela. Seljačka knjiga, Sarajevo (short story collection)

- 1954 Prokleta avlija. Matica srpska, Novi Sad (novella)

- 1958 Panorama. Prosveta, Belgrade (short story)

- 1960 Priča o vezirovom slonu, i druge pripovetke. Rad, Belgrade (short story collection)

- 1966 Ljubav u kasabi: Pripovetke. Nolit, Belgrade (short story collection)

- 1968 Aska i vuk: Pripovetke. Prosveta, Belgrade (short story collection)

- 1976 Eseji i kritike. Svjetlost, Sarajevo (essays; posthumous)

- 2000 Pisma (1912–1973): Privatna pošta. Matica srpska, Novi Sad (private correspondence; posthumous)

Explanatory notes

- Though of Croat origin, Andrić came to identify as a Serb upon moving to Belgrade.[1] Above all, he is renowned for his contributions to Serbian literature. As a youth, he wrote in his native Ijekavian dialect, but switched to Serbia's Ekavian dialect while living in the Yugoslav capital.[2][3] The Nobel Committee lists him as a Yugoslav and identifies the language he used as Serbo-Croatian.[4]

- Ivo is the hypocoristic form of Andrić's birth name, Ivan. The latter was used on his birth and marriage certificates, but all other documents read "Ivo".[5]

- The full name of the group was The Croat-Serb or Serb-Croat or Yugoslav Progressive Youth Movement.[19]

- On one occasion, Princip asked Andrić to examine a poem he had written. Later, when Andrić inquired about the poem, Princip told him that he had destroyed it.[26]

- Disagreement exists as to the exact date. Hawkesworth writes that Andrić was arrested on 29 July,[25] while Vucinich gives the date as 4 August.[24]

- "Unrest" is Vucinich's translation of the title.[32] Hawkesworth translates it as "Anxieties".[31]

- Hawkesworth and Vucinich translate Travnička hronika as "Bosnian Story".[44][45] "Travnik Chronicle" is a more accurate translation.[46]

- Hawkesworth writes that Andrić was appointed on 1 April.[35] Vucinich gives the date as 28 March.[44]

- In early 1944, there were rumours that Andrić and several other prominent writers from Serbia were planning to join the Chetniks. This may have been Chetnik propaganda to counteract the news that a number of intellectuals were swearing allegiance to the Partisans.[58]

- Andrić was perturbed by a billboard that the Partisans had put up in Terazije Square, a photograph of the signing of the Tripartite Pact with his face clearly visible. The billboard was part of a propaganda campaign against the royalists and Andrić perceived it as an indictment of his actions while ambassador to Germany. In a subsequent conversation with senior communist official Milovan Đilas, he requested that the billboard be removed, and Đilas obliged.[59]

- "The Woman from Sarajevo" is Hawkesworth and Vucinich's translation of the title.[44][45] A more literal translation is "The Young Lady".[60]

- An ethno-town or ethno-village is a tourist attraction that is designed to resemble a traditional settlement inhabited by a particular group of people. Kusturica had previously constructed Drvengrad, an ethno-village in Western Serbia.[88]

References

Citations

- Lampe 2000, p. 91.

- Norris 1999, p. 60.

- Alexander 2006, p. 391.

- Frenz 1999, p. 561.

- Juričić 1986, p. 1.

- Norris 1999, p. 59.

- Lampe 2000, p. 91; Hoare 2007, p. 90; Binder 2013, p. 41.

- Hawkesworth 1984, p. 11.

- Juričić 1986, p. 2.

- Vucinich 1995, p. 1.

- Hawkesworth 1984, p. 3.

- Hoare 2007, p. 90.

- Vucinich 1995, p. 2.

- Hawkesworth 1984, p. 13.

- Hawkesworth 1984, p. 14.

- Vucinich 1995, p. 28.

- Dedijer 1966, p. 230.

- Vucinich 1995, p. 20.

- Malcolm 1996, p. 153.

- Dedijer 1966, p. 216.

- Vucinich 1995, pp. 26–27.

- Hawkesworth 1984, p. 41.

- Lampe 2000, p. 90.

- Vucinich 1995, p. 29.

- Hawkesworth 1984, p. 15.

- Dedijer 1966, p. 194.

- Dedijer 1966, p. 233.

- Hawkesworth 1984, p. 16.

- Vucinich 1995, p. 30.

- Hawkesworth 1984, p. 17.

- Hawkesworth 1984, p. 18.

- Vucinich 1995, p. 31.

- Malcolm 1996, p. 304, note 52.

- Hawkesworth 1984, p. 19.

- Hawkesworth 1984, p. 20.

- Vucinich 1995, p. 32.

- Popović 1989, p. 36.

- Hawkesworth 1984, p. 22.

- Hawkesworth 1984, p. 23.

- Vucinich 1995, p. 33.

- Carmichael 2015, p. 62.

- Malcolm 1996, p. 100.

- Hawkesworth 1984, p. 24.

- Vucinich 1995, p. 34.

- Hawkesworth 1984, p. 28.

- Google Translate, Travnička hronika.

- Popović 1989, p. 46.

- Hawkesworth 1984, p. 25.

- Hawkesworth 1984, p. 26.

- Bazdulj 2009, p. 225.

- Lampe 2000, pp. 199–200.

- Hawkesworth 1984, p. 27.

- Popović 1989, p. 54.

- Pavlowitch 2008, p. 97.

- Juričić 1986, p. 55.

- Prusin 2017, p. 48.

- Wachtel 1998, p. 156.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 193, note 55.

- Bazdulj 2009, p. 227.

- Google Translate, Gospođica.

- Moravcevich 1980, p. 23.

- Vucinich 1995, p. 35.

- Hawkesworth 1984, p. 29.

- BBC News 6 January 2012.

- Flood 5 January 2012.

- Lovrenović 2001, pp. 182–183.

- Hawkesworth 1984, p. 30.

- Vucinich 1995, p. 36.

- Popović 1989, p. 112.

- Vucinich 1995, pp. 2–3.

- Vucinich 1995, p. 3.

- Wachtel 1998, p. 161.

- Carmichael 2015, p. 107.

- Wachtel 1998, p. 216.

- Norris 2008, pp. 100, 237.

- Google Maps, Novi Sad, Google Maps, Kragujevac

- Google Maps, Sarajevo, Google Maps, Banja Luka, Google Maps, Tuzla, Google Maps, Višegrad

- Norris 1999, p. 61.

- Aleksov 2009, p. 273.

- Perica 2002, p. 188.

- Cornis-Pope 2010, p. 569.

- Banac 1992, p. xiii.

- Primorac 6 September 2012.

- Snel 2004, p. 210.

- Rakić 2000, pp. 82–87.

- Silber 20 September 1994.

- Radio Television of Serbia 9 April 2009.

- Lagayette 2008, p. 12.

- Jukic 29 June 2012.

- Aspden 27 June 2014.

Works cited

- Alexander, Ronelle (2006). Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian: A Grammar with Sociolinguistic Commentary. Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-21193-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Aleksov, Bojan (2009). "Jovan Jovanović Zmaj and the Serbian Identity Between Poetry and History". In Mishkova, Diana (ed.). We, the People: Politics of National Peculiarity in Southeastern Europe. Budapest, Hungary: Central European University Press. ISBN 978-9-63977-628-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Aspden, Peter (27 June 2014). "The town that Emir Kusturica built". Financial Times.

- Banac, Ivo (1992). "Foreword". In Ramet, Sabrina P. (ed.). Balkan Babel: Politics, Culture and Religion in Yugoslavia. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. pp. ix–xiv. ISBN 978-0-81338-184-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bazdulj, Muharem (2009). "The Noble School". The Wall in My Head: Words and Images from the Fall of the Iron Curtain. Rochester, New York: Open Letter Books. ISBN 978-1-93482-423-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Binder, David (2013). Farewell, Illyria. Budapest, Hungary: Central European University Press. ISBN 978-615-5225-74-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carmichael, Cathie (2015). A Concise History of Bosnia. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-10701-615-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cornis-Pope, Marcel (2010). "East-Central European Literature after 1989". In Cornis-Pope, Marcel; Neubauer, John (eds.). Types and Stereotypes. History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe. 4. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-8786-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dedijer, Vladimir (1966). The Road to Sarajevo. New York City: Simon & Schuster. OCLC 400010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Flood, Alison (5 January 2012). "JRR Tolkien's Nobel prize chances dashed by 'poor prose'". The Guardian.

- Google (7 January 2015). "Banja Luka" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- Google (7 January 2015). "Kragujevac" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- Google (7 January 2015). "Novi Sad" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- Google (7 January 2015). "Sarajevo" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- Google (7 January 2015). "Tuzla" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- Google (7 January 2015). "Višegrad" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- "Gospođica". Google Translate. Retrieved 25 December 2015.

- "Travnička hronika". Google Translate. Retrieved 25 December 2015.

- Frenz, Horst (1999). Literature: 1901–1967. Singapore: World Scientific. ISBN 978-9-8102-3413-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hawkesworth, Celia (1984). Ivo Andrić: Bridge Between East and West. London, England: Athlone Press. ISBN 978-1-84714-089-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hoare, Marko Attila (2007). The History of Bosnia: From the Middle Ages to the Present Day. London, England: Saqi. ISBN 978-0-86356-953-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Imam presudio: Ivo Andrić "četnički ideolog"". Radio Television of Serbia. 9 April 2009.

- "JRR Tolkien snubbed by 1961 Nobel jury, papers reveal". BBC News. 6 January 2012.

- Jukic, Elvira (29 June 2012). "Kusturica and Dodik Unveil Andric Sculpture in Bosnia". Balkan Insight.

- Juričić, Želimir B. (1986). The Man and the Artist: Essays on Ivo Andrić. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-81914-907-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lagayette, Pierre (2008). Leisure and Liberty in North America. Paris, France: Presses Paris Sorbonne. ISBN 978-2-84050-540-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lampe, John R. (2000) [1996]. Yugoslavia as History: Twice There Was a Country (2nd ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77401-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lovrenović, Ivan (2001). Bosnia: A Cultural History. London, England: Saqi. ISBN 978-0-86356-946-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Malcolm, Noel (1996) [1994]. Bosnia: A Short History. New York City: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-5520-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moravcevich, Nicholas (1980). "Andrić, Ivo". In Bédé, Jean Albert; Edgerton, William Benbow (eds.). Columbia Dictionary of Modern European Literature (2nd ed.). New York City: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-23103-717-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Norris, David A. (1999). In the Wake of the Balkan Myth: Questions of Identity and Modernity. New York City: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-23028-653-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Norris, David A. (2008). Belgrade: A Cultural History. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-970452-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2008). Hitler's New Disorder: The Second World War in Yugoslavia. New York City: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-1-85065-895-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Perica, Vjekoslav (2002). Balkan Idols: Religion and Nationalism in Yugoslav States. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19517-429-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Popović, Radovan (1989). Ivo Andrić: A Writer's Life. Belgrade, Yugoslavia: Ivo Andrić Endowment. OCLC 22400098.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Primorac, Strahimir (2012). "Izazovan poziv na čitanje Andrića". Vijenac (in Croatian). Matica hrvatska (482).

- Prusin, Alexander (2017). Serbia Under the Swastika: A World War II Occupation. Chicago, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-25209-961-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rakić, Bogdan (2000). "The Proof is in the Pudding: Ivo Andrić and His Bosniak Critics" (PDF). Journal of the North American Society for Serbian Studies. Bloomington, Indiana: Slavica Publishers. 14 (1): 81–91. ISSN 0742-3330. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Silber, Laura (20 September 1994). "A Bridge of Disunity". Los Angeles Times.

- Snel, Guido (2004). "The Footsteps of Gavrilo Princip". In Cornis-Pope, Marcel; Neubauer, John (eds.). History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe: Junctures and Disjunctures in the 19th and 20th Centuries. History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe. 1. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-27234-52-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Swedish Academy (2007). "Ivo Andrić: Bibliography". Nobel Prize.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (1975). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: The Chetniks. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0857-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vucinich, Wayne S. (1995). "Ivo Andrić and His Times". In Vucinich, Wayne S. (ed.). Ivo Andrić Revisited: The Bridge Still Stands. Oakland, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-87725-192-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wachtel, Andrew Baruch (1998). Making a Nation, Breaking a Nation: Literature and Cultural Politics in Yugoslavia. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-80473-181-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Ivo Andrić |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ivo Andrić. |

- Ivo Andrić on Nobelprize.org

- Ivo Andrić Foundation

- Ivo Andrić Museum