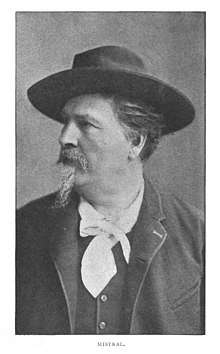

Frédéric Mistral

Frederic Mistral (French: [mistʁal]; Occitan: Josèp Estève Frederic Mistral, 8 September 1830 – 25 March 1914) was an Occitan writer and lexicographer of the Occitan language. Mistral received the 1904 Nobel Prize in Literature "in recognition of the fresh originality and true inspiration of his poetic production, which faithfully reflects the natural scenery and native spirit of his people, and, in addition, his significant work as a Provençal philologist". He was a founding member of Félibrige and a member of l'Académie de Marseille.

Frédéric Mistral | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 8 September 1830 Maillane, France |

| Died | 25 March 1914 (aged 83) Maillane, France |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Nationality | France |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Literature 1904 |

His name in his native language was Frederi Mistral (Mistrau) according to the Mistralian orthography or Frederic Mistral (or Mistrau) according to the classical orthography.

Mistral's fame was owing in part to Alphonse de Lamartine who sang his praises in the 40th edition of his periodical Cours familier de littérature, following the publication of Mistral's long poem Mirèio. Alphonse Daudet, with whom he maintained a long friendship, eulogized him in "Poet Mistral", one of the stories in his collection Letters from My Windmill (Lettres de mon moulin).

Biography

Mistral was born in Maillane in the Bouches-du-Rhône département in southern France.[1] His parents were wealthy landed farmers.[1] His father, François Mistral, was from Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.[1] His mother was Adelaide Poulinet. As early as 1471, his paternal ancestor, Mermet Mistral, lived in Maillane.[1] By 1588, the Mistral family lived in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.[1]

Mistral was given the name "Frederi" in memory "of a poor small fellow who, at the time when my parents were courting, sweetly ran their errands of love, and who died shortly afterward of sunstroke."[2] Mistral did not begin school until he was about nine years, and quickly began to play truant, leading his parents to send him to a boarding school in Saint-Michel-de-Frigolet, run by a Monsieur Donnat.

After receiving his bachelor's degree in Nîmes, Mistral studied law in Aix-en-Provence from 1848 to 1851. He became a champion for the independence of Provence, and in particular for restoring the "first literary language of civilized Europe"—Provençal. He had studied the history of Provence during his time in Aix-en-Provence. Emancipated by his father, Mistral resolved: "to raise, revive in Provence the feeling of race ...; to move this rebirth by the restoration of the natural and historical language of the country ...; to restore the fashion to Provence by the breath and flame of divine poetry". For Mistral, the word race designates "people linked by language, rooted in a country and in a story".

For his lifelong efforts in restoring the language of Provence, Frédéric Mistral was one of the recipients of the 1904 Nobel Prize for Literature after having been nominated by two professors from the Swedish Uppsala University.[3][4] The other winner that year, José Echegaray, was honored for his Spanish dramas. They shared the prize money equally.[5] Mistral devoted his half to the creation of the Museum at Arles, known locally as "Museon Arlaten". The museum is considered to be the most important collection of Provençal folk art, displaying furniture, costumes, ceramics, tools and farming implements. In addition, Mistral was awarded the Légion d'honneur. This was a most unusual occurrence since it is usually only awarded for notable achievement on a national level whereas Mistral was uniquely Provençal in his work and achievement.

In 1876, Mistral married a Burgundian woman, Marie-Louise Rivière (1857–1943) in Dijon Cathedral (Cathédrale Saint-Bénigne de Dijon). They had no children. The poet died on 25 March 1914 in Maillane, the same village where he was born.

Félibrige

Mistral joined forces with one of his teachers, Joseph Roumanille, and five other Provençal poets and on 21 May 1854, they founded Félibrige, a literary and cultural association, which made it possible to promote the Occitan language. Placed under the patronage of Saint Estelle, the movement also welcomed Catalan poets from Spain, driven out by Isabelle II.

The seven founders of the organization were (to use their Provençal names): Jóusè Roumaniho, Frederi Mistral, Teodor Aubanel, Ansèume Matiéu, Jan Brunet, Anfos Tavan and Paul Giera. Félibrige exists to this day, one of the few remaining cultural organizations in 32 departments of the "Langue d'Oc".

Mistral strove to rehabilitate the language of Provence, while carrying it to the highest summits of epic poetry. He redefined the language in its purest form by creating a dictionary and transcribing the songs of the troubadours, who spoke the language in its original form.

Lexicography: Lou Tresor dóu Felibrige

Mistral is the author of Lou Tresor dóu Félibrige (1878–1886), which to date remains the most comprehensive dictionary of the Occitan language, and one of the most reliable, thanks to the precision of its definitions. It is a bilingual dictionary, Occitan-French, in two large volumes, with all of the dialects of oc, including Provençal. Mistral owes to François Vidal the work of typesetting and revising that dictionary.

Mirèio – Mireille

Mistral's most important work is Mirèio (Mireille), published in 1859, after eight years of effort. Mirèio, a long poem in Provençal consisting of twelve songs, tells of the thwarted love of Vincent and Mireille, two young Provençal people of different social backgrounds. The name Mireille (Mirèio in Provence) is a doublet of the word meraviho which means wonder.

Mistral used the occasion not only to promote his language but also to share the culture of an area. He tells among other tales, of Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, where according to legend the dragon, Tarasque, was driven out, and of the famous and ancient Venus of Arles. He prefaced the poem with a short notice about Provençal pronunciation.

The poem tells how Mireille's parents wish her to marry a Provençal landowner, but she falls in love with a poor basket maker named Vincent, who loves her as well. After rejecting three rich suitors, a desperate Mireille, driven by the refusal of her parents to let her marry Vincent, runs off to Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer to pray to the patrons of Provence to change her parents' minds. Having forgotten to bring a hat, she falls victim to the heat, dying in Vincent's arms under the gaze of her parents.

Mistral dedicated his book to Alphonse Lamartine as follows:

"To Lamartine:

To you, I dedicate Mireille: It is my heart and my soul; It is the flower of my years; It is bunch of grapes from La Crau, leaves and all, a peasant's offering."

Lamartine wrote enthusiastically: "I will tell you good news today! A great epic poet is born ... A true Homeric poet in our time; ... Yes, your epic poem is a masterpiece; ... the perfume of your book will not evaporate in a thousand years."

Mirèio was translated into some fifteen European languages, including into French by Mistral himself. In 1863, Charles Gounod made it into an opera, Mireille.

Quotations

- « Les arbres aux racines profondes sont ceux qui montent haut. »

- "Trees with deep roots grow tall."

- « Les cinq doigts de la main ne sont pas tous égaux. »

- "The five fingers of the hand are not all equal."

- « Quand le Bon Dieu en vient à douter du monde, il se rappelle qu'il a créé la Provence. »

- "When the Good Lord begins to doubt the world, he remembers that he created Provence."

- « Chaque année, le rossignol revêt des plumes neuves, mais il garde sa chanson. »

- "Each year, the nightingale dresses with new feathers, but it keeps the same song."

- « Le soleil semble se coucher dans un verre de Tavel aux tons rubis irisés de topaze. Mais c'est pour mieux se lever dans les cœurs. »

- "The sun appears to set with iridescent ruby tones of topaz in a glass of Tavel. But it is to rise stronger in the hearts."

- « La Provence chante, le Languedoc combat »

- "Provence sings, Languedoc fights"

- « Qui a vu Paris et pas Cassis, n'a rien vu. (Qu'a vist París e non Cassís a ren vist.) »

- "He who has seen Paris and not Cassis has seen nothing."

Works

- Mirèio (1859) - PDF (in Provençal)

- Calendau (1867) - online

- Lis Isclo d’or (1875) - en ligne : part I, part II

- Nerto, short story (1884) - online

- La Rèino Jano, drama (1890) - en ligne

- Lou Pouèmo dóu Rose (1897) - online

- Moun espelido, Memòri e Raconte (Mes mémoires) (1906) - online

- Discours e dicho (1906) - online

- La Genèsi, traducho en prouvençau (1910) - online

- Lis óulivado (1912) - online

- Lou Tresor dóu Felibrige ou Dictionnaire provençal-français embrassant les divers dialectes de la langue d'oc moderne (1878–1886) - online

- Proso d’Armana (posthume) (1926, 1927, 1930) - online

- Coupo Santo (1867)

See also

- The works of Antonin Mercié

- List of works by Louis Botinelly

References

- Busquet, Raoul; Rollane, Henri (1951). "La généalogie de Mistral". Revue d'Histoire littéraire de la France. 1 (1): 52–60. JSTOR 40520865.

- (in French) Frédéric Mistral. Mes origines : mémoires et récits de Frédéric Mistral. Paris: Plon-Nourrit, ca 1920. Page 9.

- "Nomination Database". www.nobelprize.org.

- "Nomination Database". www.nobelprize.org.

- "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1904". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

Sources

- Mistral, Frédéric (1915) [1906]. Mes Origines: Mémoires et Récits de Frédéric Mistral (Traduction du provençal) (in French). Paris: Plon-Nourrit.

- Mistral, Frédéric; Maud, Constance Elizabeth (translator) (1907). Memoirs of Mistral. London: Edward Arnold.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Frédéric Mistral. |

- Frédéric Mistral on Nobelprize.org with the prize motivation

- Works by Frédéric Mistral at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Frédéric Mistral at Internet Archive

- List of Works

- Works by Frédéric Mistral at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Frédéric Mistral Biography

- The life of Frederic Mistral - NotreProvence.fr

- The Memoirs of Frédéric Mistral by Frédéric Mistral and George Wickes (1986) English translation of Mistral's autobiography

- Museon Arlaten (in French)

- Félix Charpentier.Le Jardin des Félibres sculpture depicting Mistral