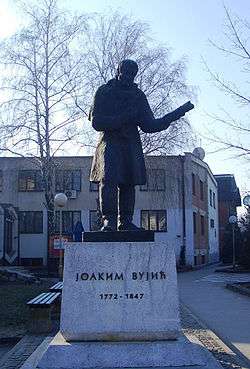

Joakim Vujić

Joakim Vujić (Serbian Cyrillic: Јоаким Вујић; 1772, Baja, Habsburg Monarchy – 1847) was a Serbian writer, dramatist (musical stage and theatre), actor, traveler and polyglot. He was one of the most accomplished Serbian dramatists and writers of the 18th century, director of Knjaževsko-srpski teatar (The Royal Serbian Theatre) in Kragujevac 1835/36. He is known as the Father of Serbian Theatre.[1]

Joakim Vujić | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 9 September 1772 Baja, Kingdom of Hungary, Habsburg Monarchy (today Hungary) |

| Occupation | Writer, dramatist, actor and traveler |

| Nationality | Serbian |

Biography

Vujić was born on 9 September 1772 in Baja, a small town on the bank of the Danube which had been granted, as early as 1696, special privileges by Emperor Leopold I as a "Serbian town" (though it had always been so for a long time). His ancestors (then living in Ottoman-occupied South Serbia) arrived to this region (Rascia or Rászság of the southern Pannonian Plain) seeking refuge from the Ottoman Turks.

Vujić went to school in Baja. First he attended a Slav-Serbian school and then he proceeded to Latin, German and Hungarian schools. He was further educated in Novi Sad, Kalocsa and Bratislava (the Evangelical Licaeum and the Roman Catholic Academy). He became a teacher and earned his living chiefly as a teacher of foreign languages. He was an ardent supporter of Enlightenment and his model was Dositej Obradović, whom he met personally in Trieste's Serbian community before Dositej left for Karađorđe's Serbia. Joakim Vujić was a polyglot and spoke Italian, German, French, English, Hungarian and, of course, Greek and Latin. He also learnt some Hebrew.

His career as a dramatic author began with the exhibition of a drama in or about the year 1813, and continued for almost thirty years. Prior to 1813 he incurred the hostility of the Austrian authorities, especially, it is said, of the Habsburgs, by the attacks which he made upon them on the stage in Zemun, and at their instance he was imprisoned for a while. After writing a play during his imprisonment, in which he is said to have recanted, he was freed. His many travels and literary accomplishments established his influence in the new Serbian capital—Kragujevac—once and for all and at the same time knitted him closely to Prince Miloš, who recognized in him a man after his own heart, and made him the knaževsko-srbskog teatra direktor, the director of the Royal Serbian Theatre.[2]

He made several voyages to the Black Sea and to different places in southern Russia before returning in 1842 back in Serbia, where he died on 8 November 1847.[3]

Work and importance

He was one of the most productive Serbian writers of his time and left about fifty works. He published slightly more than a half of them. Some are still in manuscript, and one was destroyed in World War II, when the National Library in Belgrade, in which his manuscripts were kept, was demolished in an air raid. He translated and adapted dramatic works (from German and Hungarian), wrote travel books, geographical text-books and translated novels. He compiled the first French grammar in the Serbian language (1805). He wrote in the so-called Slavo-Serbian language, a variant very close to the language of the people. Many Serbs subscribed to his publications, and he was, together with novelist Milovan Vidaković, one of the most widely read Serbian authors of his time. As such, he exercised a considerable influence on the broadening of the reading public among the Serbs. He seems to have also been among the first Serbian writers of travel books, for he began to write his first travel account as early as 1803, while touring Italy. His more important books of this kind are Travels in Serbia (1828) and Travels in Hungary, Wallachia, and Russia (1845). His famous autobiography – My Life—was also written in the form of a travel book.

Vujić lived and wrote in the time of the French Revolution (1789). He was a witness of the Napoleonic Wars, the Serbian Revolutions, the actions of the Holy Alliance, and other great events in Europe in the period between the two revolutions (1789–1848): He wrote at the time of the awakening of the nations in the Balkans and South-East Europe. In his writings and theatrical work he propagated progressive views, liberty, human rights, ethical ideas, and international co-operation. Although he belonged by birth to a distant and alienated branch of the Serbian people, he was determined to get to know his mother country well, to return to it and to serve it as an intellectual and patriot.

Theatre

Vujić is best known and most esteemed for his work for the theatre. In fact, it was Joakim Vujić who organized stage performances among the Serbs of Habsburg Monarchy and the Principality of Serbia. There were Serbian theatrical companies at the time in Novi Sad, Pančevo, Kikinda, Sombor and other places in Vojvodina. The Theatre of the Princedom of Serbia was established in 1834 in Kragujevac, the capital of the newly formed Principality. It continued also when the capital was moved to Belgrade in 1841.

Vujić is the organizer of the first theatrical performance in Serbian, which took place in the Hungarian theatre "Rondella" in Budapest on 24 August 1813.[4] From 1813, if not earlier, to 1839 he organised, with the help of secondary school pupils and adult amateurs, performances in the Serbian language in many towns of the Austrian Empire – Sent Andreja (1810–1813), Budapest (1813), Baja (1815), Szeged (1815), Novi Sad (1815, 1838), Pančevo (1824, 1833, 1835, 1837, 1839), Zemun (1824), Temesvar (1824), Arad (1832) and Karlovac (1833). He founded the Serbian Theatre in Kragujevac, the capital of the restored Serbian state, and became its first director (1834–1836). This was the first state and court theatre in the Serbia of Miloš Obrenović I, Prince of Serbia; Joakim Vujić was the only professional in it and he had the entire capital at his disposal when he prepared performances for the Prince and the representatives of the people.

He advocated the presentation of plays in the Serbian language in Novi Sad (1833), where he collaborated with the so-called Flying Dilettante Theatre, which gave the first performance in Serbo-Croat in Zagreb at the invitation of the Illyrian Library and which became the first professional theatrical company in the Balkans (1840–1842). A considerable number of the members of this company came later to Belgrade, where they took part in the work of the "Theatre at Djumruk" and helped establish the first professional theatre in Belgrade in 1842.

Vujić has been justly called the "Serbian Thespis" and "the father of the Serbian theatre", for he was the first Serb to engage in practical theatrical work and to organize theatrical performances. In this activity, he profited much by the experience of Italian, German and Hungarian theatres. The first developmental phase of modern Serbian musical culture also began with the cooperation of Joakim Vujić and Sombor-born, composer Jožef Šlezinger (1794–1870).

Joakim Vujić translated or adapted 28 dramatic works. He was chiefly interested in German drama and August von Kotzebue seems to have been his favourite playwright, for he translated eight of Kotzebue's plays. He began his "studies of theatre arts" in Bratislava during his regular studies; he continued them in Trieste in Italy, and completed them in Budapest (1810–1815). The crucial event in his theatrical career was the performance of István Balog's heroic play about Karađorđe and the liberation of Belgrade, presented in the Hungarian Theatre in Budapest in 1812. István Balog's great success of "Black George" (Karađorđe) led to collaboration between Balog's theatre company and Joakim Vujić who was then the lecturer of a Serbian teacher-training college in Szentendre. The cooperation resulted in two of Vujić's undertakings: the founding of a Serbian theatre company and translation of Balog's "Karađorđe" play into the Serbian language. After Vujić translated this play, he was not permitted to publish it. Nevertheless, he used his manuscript in preparing the play for a bilingual performance which was given by both Serbian and Hungarian actors, including Joakim Vujić as well as István Balog. The translation, however, was only published three decades later in Novi Sad (1843).

Vujić was one of the rare writers and cultural workers of his time who made his living by writing. His autobiography was a remarkable achievement of the printing craft: the work is written in Serbian (or rather Slav-Serbian) but it contains a number of passages, letters, documents and fragments quoted in several modern and classical languages, and each of them is printed in the corresponding type. Thus the book contains Serbian, Latin, Italian, French, Hungarian, English, German, Hebrew, and Greek texts, all printed in the appropriate alphabet.

For a long time, Vujić was a solitary theatrical enthusiast among the Serbs. He himself was a veritable theatrical laboratory – he was not only the translator and adapter of the plays he produced, but also the director, chief organiser, actor, scenographer, costume designer, prompter, and technical manager. He advocated the establishment of a national theatre for the people, but he also carried in his luggage neatly transcribed roles and cords for stage curtains. In short, he himself represented an entire small theatrical system. He gave successful performances, in each town he visited, relying on the support of Serbian schools and churches. He left behind him groups of inspired young people who continued his work, establishing theatres in their own language. He worked in the time of the monstrous censorship of Metternich's police regime and he was fully aware of the rigidity of the official measures, for his work was under constant police surveillance.

His productions of "Black George or The Liberation of Belgrade from the Turks" in Szeged (1815) and Novi Sad (1815) set into motion the complex machinery of the Imperial military and civilian censorship, which put a stop to the further presentation of the play and other similar productions.

He produced about 25–30 plays in all, each of which represented a specific national and cultural achievement. He usually staged his own translations and adaptations, and he ended his theatrical career with a production of Jovan Sterija Popović's popular comedy "Kir Janja" (Pančevo, 1839).

His theatre was a theatre of Enlightenment, and its aim was to edify the people and to heighten their national consciousness. Although he cherished the idea of a national theatre as a permanent professional system, he did not succeed in creating a lasting national theatre in the Slav-Serbian language. Nevertheless, he constantly insisted upon it as an aim to be aspired to. He believed that such a theatre would provide an important link with the cultures of the other European countries. The permanent national theatre was to come into being a little later, after the triumph of Vuk's linguistic and cultural reform, when the Serbian National Theatre in Novi Sad (1861) and the National Theatre in Belgrade (1868) were established.

The versatile activity of Joakim Vujić belongs to many cultural spheres and disciplines. His work is of interest to various students of the Serbian cultural heritage – to ethnologists, philologists, philosophers, historians, cultural activists, historians of art, historians of education and andragogy, experts on theatrical organisation, folklorists, theatrologists, costume designers, psychologists, sociologists, aestheticians, and, in a broader sense, Balcanologists and all those involved in the study of the general position of cultural workers and intelligentsia in repressive societies.

Towards the end of his life Vujić applied to the court of Karađorđe Petrović for a pension in recognition of his edificatory, cultural, literary and theatrical work. He did not get it, but he was one of the first cultural workers and authors in Serbia to claim social recognition and material reward for his service to the people.

Vujić was a mediator between the Serbian and Yugoslav culture and the cultures in the Italian, German, Hungarian, French and English languages. He was also interested in the life, customs, laws, language and religion of the Mohammedans. In fact, he was one of the rare mediators between the Western Christian and the Eastern Islamic cultures. His activity was of great value to the Serbs, because it helped them to become integrated, at least partly, into the European cultural system.

The earliest and least polished stone in the foundations of the Serbian and Yugoslav theatre was laid by Joakim Vujic as far back as 1813 when he produced the first secular play in the Serbian language. It is the 175th anniversary of that event that we are celebrating today. His work was almost completely forgotten for a long time, and the first to draw attention to him was the great Serbian dramatist Branislav Nušić, who proposed in 1900 to publish Vujić's plays in his projected Serbian Dramatic Miscellany. Unfortunately, the Miscellany was never published. Only the Royal National Theatre in Belgrade produced two of Vujić's works on the occasion of its 30th anniversary, thus paying homage to the "father of the Serbian theatre". Between the two world wars, his works were not staged in Serbian professional theatres.

Legacy under Communism

Soon after World War II and the formation of socialist Yugoslavia, the Yugoslav dramatic heritage was made an object of study in the newly established Academies for Theatre Arts in Belgrade, Zagreb and Ljubljana. The events of 1948 contributed further to this search for cultural identity. The well-known production "The Theatre of Joakim Vujić", first shown in the vanguard theatre "Atelje 212" in Belgrade on 13 November 1958 (produced by Vladimir Petrić and directed by Josip Kulundžić, the founder of the Department of Dramaturgy in the Academy for Theatre Arts in Belgrade) marked not only the return of Vujić's works to the Serbian stage, but also his artistic and personal rehabilitation.

Works

- Fernando i Jarika, jedna javnaja igra u trima djejstvijima, Budim 1805. godine,

- Ljubovna zavist črez jedne cipele, jedna veselaja igra u jednom djejstviju, Budim 1807. godine,

- Nagraždenije i nakazanije, jedna seoska igra u dva djejstvija, Budim 1809. godine,

- Kreštalica, jedno javno pozorište u tri djejstvija, Budim 1914. godine,

- Serpski vožd Georgij Petrovič, inače rečeni Crni ili Otjatije Beograda od Turaka. Jedno iroičesko pozorište u četiri djejstvija, Novi Sad 1843. godine,

- Šnajderski kalfa, jedna vesela s pesmama igra u dva djejstvija, Beograd 1960. godine. Nabrežnoje pravo, dramatičeskoje pozorje, Beograd 1965. godine,

- Dobrodeljni derviš ili Zveketuša kapa, jedna volšebna igra u tri djejstvija, Kragujevac 1983. godine.[5]

- Španjoli u Peruviji ili Rolova smert, 1812,

- Nabrežnoje pravo, 1812,

- Žertva smerti, 1812,

- Sibinjska šuma, 1820,

- Negri ili Ljubov ko sočolovjekom svojim, 1821,

- Preduvjerenije sverhu sostojanija i roždenija, 1826,

- Dobrodeljni derviš ili Zveketuša kapa, 1826,

- Sestra iz Budima ili Šnajderski kalfa, 1826,

- Paunika Jagodinka, 1832,

- La Pejruz ili Velikodušije jedne divje, 1834,

- Ljubovna zavist črez jedne cipele, 1805,

- Stari vojak, 1816,

- Kartaš, 1821,

- Devojački lov 1826,

- Obručenije ili Djetska dolžnost sverhu ljubve, 1826,

- Svake dobre vešči jesu tri, 1826,

- Siroma stihotvorac, 1826,

- Seliko i Beriza ili LJubav izmeždu Negri, 1826,

- Siroma tamburdžija, 1826,

- Serbska princeza Anđelija, 1837,

- Djevica iz Marijenburga, 1826,

- Znajemi vampir, 1812.

References

- http://www.joakimvujic.com/english.php Archived 8 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine Knjaževsko-srpski teatar

- "BAČVANIN KOJI JE UTEMELJIO POZORIŠNI ŽIVOT U SRBA (JOAKIM VUJIĆ) – Ravnoplov". Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- http://joakimvujic.com/news.php#joakim Archived 13 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine Joakim Vujić (1772–1847)

- Pan-Montojo, Juan; Pedersen, Frederik (2007). Communities in European History: Representations, Jurisdictions, Conflicts. ISBN 9788884924629.

- Prof. Alojz Ujes Pozorišno stvaranje i trajanje Joakima Vujića 1805–1985, Kragujevac 1985. godine.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Joakim Vujić. |

- Biography

- Jovan Skerlić, Istorija Nove Srpske Književnosti / History of Modern Serbian Literature (Belgrade, 1921), pp. 143–145.