Giorgos Seferis

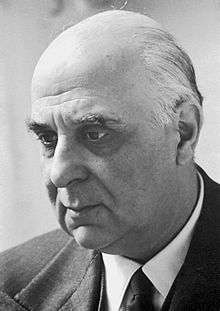

Giorgos or George Seferis (/səˈfɛrɪs/; Greek: Γιώργος Σεφέρης [ˈʝorɣos seˈferis]), the pen name of Georgios Seferiades (Γεώργιος Σεφεριάδης; March 13 [O.S. February 29] 1900 – September 20, 1971), was a Greek poet-diplomat. He was one of the most important Greek poets of the 20th century, and a Nobel laureate. He was a career diplomat in the Greek Foreign Service, culminating in his appointment as Ambassador to the UK, a post which he held from 1957 to 1962.

Giorgos Seferis | |

|---|---|

Giorgos Seferis at age 21 (1921) | |

| Born | Georgios Seferiades March 13 [O.S. February 29] 1900 Urla, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | September 20, 1971 (aged 71) Athens, Regime of the Colonels |

| Occupation | Poet, diplomat |

| Nationality | Greek |

| Alma mater | University of Paris |

| Literary movement | Modernism, Generation of the '30s[1] |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Literature 1963 |

| Signature |  |

Biography

Seferis was born in Vourla near Smyrna in Asia Minor, Ottoman Empire (now İzmir, Turkey). His father, Stelios Seferiadis, was a lawyer, and later a professor at the University of Athens, as well as a poet and translator in his own right. He was also a staunch Venizelist and a supporter of the demotic Greek language over the formal, official language (katharevousa). Both of these attitudes influenced his son. In 1914 the family moved to Athens, where Seferis completed his secondary school education. He continued his studies in Paris from 1918 to 1925, studying law at the Sorbonne. While he was there, in September 1922, Smyrna/Izmir was taken by the Turkish Army after a two-year Greek military campaign on Anatolian soil. Many Greeks, including Seferis' family, fled from Asia Minor. Seferis would not visit Smyrna again until 1950; the sense of being an exile from his childhood home would inform much of Seferis' poetry, showing itself particularly in his interest in the story of Odysseus. Seferis was also greatly influenced by Kavafis, T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound.

He returned to Athens in 1925 and was admitted to the Royal Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the following year. This was the beginning of a long and successful diplomatic career, during which he held posts in England (1931–1934) and Albania (1936–1938). He married Maria Zannou ('Maro') on April 10, 1941 on the eve of the German invasion of Greece. During the Second World War, Seferis accompanied the Free Greek Government in exile to Crete, Egypt, South Africa, and Italy, and returned to liberated Athens in 1944. He continued to serve in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and held diplomatic posts in Ankara, Turkey (1948–1950) and London (1951–1953). He was appointed minister to Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Iraq (1953–1956), and was Royal Greek Ambassador to the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1961, the last post before his retirement in Athens. Seferis received many honours and prizes, among them honorary doctoral degrees from the universities of Cambridge (1960), Oxford (1964), Thessaloniki (1964), and Princeton (1965).

In 1936, Seferis published a translation of T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land.

Cyprus

Seferis first visited Cyprus in November 1953. He immediately fell in love with the island, partly because of its resemblance, in its landscape, the mixture of populations, and in its traditions, to his childhood summer home in Skala (Urla). His book of poems Imerologio Katastromatos III was inspired by the island, and mostly written there–bringing to an end a period of six or seven years in which Seferis had not produced any poetry. Its original title Cyprus, where it was ordained for me… (a quotation from Euripides’ Helen in which Teucer states that Apollo has decreed that Cyprus shall be his home) made clear the optimistic sense of homecoming Seferis felt on discovering the island. Seferis changed the title in the 1959 edition of his poems.

Politically, Cyprus was entangled in the dispute between the UK, Greece and Turkey over its international status. Over the next few years, Seferis made use of his position in the diplomatic service to strive towards a resolution of the Cyprus dispute, investing a great deal of personal effort and emotion. This was one of the few areas in his life in which he allowed the personal and the political to mix. Seferis described his political principles as "liberal and democratic [or republican]."[2]

The Nobel Prize

In 1963, Seferis was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature "for his eminent lyrical writing, inspired by a deep feeling for the Hellenic world of culture." Seferis was the first Greek to receive the prize (followed later by Odysseas Elytis, who became a Nobel laureate in 1979). But in his acceptance speech, Seferis chose rather to emphasise his own humanist philosophy, concluding: "When on his way to Thebes Oedipus encountered the Sphinx, his answer to its riddle was: 'Man'. That simple word destroyed the monster. We have many monsters to destroy. Let us think of the answer of Oedipus." While Seferis has sometimes been considered a nationalist poet, his 'Hellenism' had more to do with his identifying a unifying strand of humanism in the continuity of Greek culture and literature. The other five finalists for the prize that year were W. H. Auden, Pablo Neruda (1971 winner), Samuel Beckett (1969 winner), Mishima Yukio and Aksel Sandemose.[3]

Later life

In 1967 the repressive nationalist, right-wing Regime of the Colonels took power in Greece after a coup d'état. After two years marked by widespread censorship, political detentions and torture, Seferis took a stand against the regime. On March 28, 1969, he made a statement on the BBC World Service , with copies simultaneously distributed to every newspaper in Athens. In authoritative and absolute terms, he stated "This anomaly must end".

Seferis did not live to see the end of the junta in 1974 as a direct result of Turkey’s invasion of Cyprus, which had itself been prompted by the junta’s attempt to overthrow Cyprus' President, Archbishop Makarios. He died in Athens, on September 20, 1971. The cause of death was reported to be pneumonia, aggravated by a stroke he had suffered after undergoing surgery for a bleeding ulcer about two months earlier.[4]

At his funeral, huge crowds followed his coffin through the streets of Athens, singing Mikis Theodorakis’ setting of Seferis’ poem 'Denial' (then banned); he had become a popular hero for his resistance to the regime. He is buried at First Cemetery of Athens.

Legacy

His house at Pangrati district of central Athens, just next to the Panathinaiko Stadium of Athens, still stands today at Agras Street.

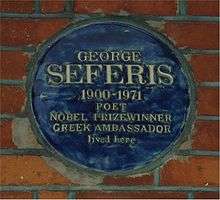

There are commemorative blue plaques on two of his London homes – 51 Upper Brook Street,[5] and at 7 Sloane Avenue.

In 1999, there was a dispute over the naming of a street in İzmir Yorgos Seferis Sokagi due to continuing ill-feeling over the Greco-Turkish War in the early 1920s.

In 2004, the band Sigmatropic released "16 Haiku & Other Stories," an album dedicated to and lyrically derived from Seferis' work. Vocalists included recording artists Laetitia Sadier, Alejandro Escovedo, Cat Power, and Robert Wyatt. Seferis' famous stanza from Mythistorema was featured in the Opening Ceremony of the 2004 Athens Olympic Games:

I woke with this marble head in my hands;

It exhausts my elbows and I don't know where to put it down.

It was falling into the dream as I was coming out of the dream.

So our life became one and it will be very difficult for it to separate again.

Stephen King quotes several of Seferis's poems in epigraphs to his 1975 novel Salem's Lot.

Works

Poetry

- Strofi Στροφή (Strophe, 1931)

- Sterna Στέρνα (The Cistern, 1932)

- Mythistorima Μυθιστόρημα (Mythical narrative, 1935)

- Tetradio Gymnasmaton Τετράδιο Γυμνασμάτων (Book of Exercises, 1940)

- Imerologio Katastromatos I Ημερολόγιο Καταστρώματος Ι ([Ship's] Log Book I, 1940)

- Imerologio Katastromatos II Ημερολόγιο Καταστρώματος ΙΙ (Log Book II, 1944)

- Kichli Κίχλη (The Thrush, 1947)

- Imerologio Katastromatos III Ημερολόγιο Καταστρώματος ΙΙΙ (Log Book III, 1955)

- Tria Kryfa Poiimata Τρία Κρυφά Ποιήματα (Three Secret Poems, 1966)

- Tetradio Gymnasmaton II Τετράδιο Γυμνασμάτων II (Book of Exercises ΙΙ, 1976)

Prose

- Dokimes (Essays) 3 vols. (vols 1–2, 3rd ed. (ed. G.P. Savidis) 1974, vol 3 (ed. Dimitri Daskalopoulos) 1992)

- Antigrafes (Translations) (1965)

- Meres (Days–diaries) (9 vols., published posthumously, 1975–2019)

- Exi nyxtes stin Akropoli (Six Nights on the Acropolis) (published posthumously, 1974)

- Varnavas Kalostefanos. Ta sxediasmata (Varnavas Kalostefanos. The drafts.) (published posthumously, 2007)

English translations

- George Seferis’s ‘On a Winter Ray’ Cordite Poetry Review [Greek and English texts]

- Complete Poems trans. Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard. (1995) London: Anvil Press Poetry. ISBN [English only]

- Collected Poems, tr. E. Keeley, P. Sherrard (1981) [Greek and English texts]

- A Poet's Journal: Days of 1945–1951 trans. Athan Anagnostopoulos. (1975) London: Harvard University Press. ISBN

- On the Greek Style: Selected Essays on Poetry and Hellenism trans. Rex Warner and Th.D. Frangopoulos. (1966) London: Bodley Head, reprinted (1982, 1992, 2000) Limni (Greece): Denise Harvey (Publisher), ISBN 960-7120-03-5

- Poems trans. Rex Warner. (1960) London: Bodley Head; Boston and Toronto: Little, Brown and Company.

- Collected Poems trans. Manolis (Emmanuel Aligizakis). (2012) Surrey: Libros Libertad. ISBN 978-1926763-23-1

- Six Nights on the Acropolis, translated by Susan Matthias (2007).

Correspondence

- This Dialectic of Blood and Light, George Seferis - Philip Sherrard, An Exchange: 1946-1971, 2015 Limni (Greece): Denise Harvey (Publisher) ISBN 978-960-7120-37-3

Notes

- Eleni Kefala, Peripheral (Post) Modernity, Peter Lang, 2007, p. 160.

- Beaton, Roderick (2003). George Seferis: Waiting for the Angel. Yale University Press. p. 456.

- "Candidates for the 1963 Nobel Prize in Literature". Nobel Prize. 2013. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- "George Seferis Dies at 71; Poet W on '63 Nobel Prize". The New York Times. September 21, 1971. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- Plaque #1 on Open Plaques.

References

- "Introduction to T. S. Eliot," in Modernism/modernity 16:1 (January 2009), 146–60 (online).

- Beaton, Roderick (2003). George Seferis: Waiting for the Angel – A Biography. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10135-X.

- Loulakaki-Moore, Irene (2010). Seferis and Elytis as Translators. Oxford: Peter Lang. ISBN 3039119184.

- Tsatsos, Ioanna, Demos Jean (trans.) (1982). My Brother George Seferis. Minneapolis, Minn.: North Central Publishing.

External links

- Edmund Keeley (Fall 1970). "George Seferis, The Art of Poetry No. 13". The Paris Review.

- Listen to Seferis on the BBC (in Greek)

- Giorgos Seferis on Nobelprize.org including the Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1963 Some Notes on Modern Greek Tradition