Vuk Karadžić

Vuk Stefanović Karadžić (pronounced [ʋûːk stefǎːnoʋitɕ kâradʒitɕ], Serbian Cyrillic: Вук Стефановић Караџић; 7 November 1787 – 7 February 1864) was a Serbian philologist and linguist. He was one of the most important reformers of the modern Serbian language.[1][2][3][4] For his collection and preservation of Serbian folktales, Encyclopædia Britannica labelled him "the father of Serbian folk-literature scholarship."[5] He was also the author of the first Serbian dictionary in the new reformed language. In addition, he translated the New Testament into the reformed form of the Serbian spelling and language.[6]

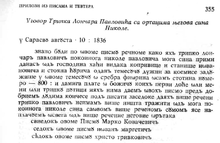

Vuk Karadžić | |

|---|---|

Vuk Karadžić, around 1850 | |

| Born | Vuk Stefanović Karadžić 7 November 1787 |

| Died | 7 February 1864 (aged 76) |

| Resting place | St. Michael's Cathedral, Belgrade, Serbia |

| Nationality | Serbian |

| Alma mater | Belgrade Higher School |

| Occupation | Philologist, linguist |

| Known for | Serbian language reform Serbian Cyrillic alphabet |

| Movement | Serbian Revival |

| Spouse(s) | Anna Maria Kraus |

| Children | 13, including Mina Karadžić |

He was well known abroad and familiar to Jacob Grimm,[7] Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and historian Leopold von Ranke. Karadžić was the primary source for Ranke's Die serbische Revolution ("The Serbian Revolution"), written in 1829.[8]

Biography

Early life

Vuk Karadžić was born to a Serbian family of Stefan and Jegda (née Zrnić) in the village of Tršić, near Loznica, which was in the Ottoman Empire (now in Serbia). His family settled from Drobnjaci, and his mother was born in Ozrinići, Nikšić (in present-day Montenegro.) His family had a low infant survival rate, thus he was named Vuk ("wolf") so that witches and evil spirits would not hurt him (the name was traditionally given to strengthen the bearer).

Education

Karadžić was fortunate to be a relative of Jevta Savić Čotrić, the only literate person in the area at the time, who taught him how to read and write. Karadžić continued his education in the Tronoša Monastery in Loznica. As a boy he learned calligraphy there, using a reed instead of a pen and a solution of gunpowder for ink. In lieu of proper writing paper he was lucky if he could get cartridge wrappings. Throughout the whole region, regular schooling was not widespread at that time and his father at first did not allow him to go to Austria. Since most of the time while in the monastery Karadžić was forced to pasture the livestock instead of studying, his father brought him back home. Meanwhile, the First Serbian Uprising seeking to overthrow the Ottomans began in 1804. After unsuccessful attempts to enroll in the gymnasium at Sremski Karlovci,[9] for which 19-year-old Karadžić was too old,[10] he left for Petrinja where he spent a few months learning Latin and German. Later on, he met highly respected scholar Dositej Obradović in Belgrade, which was now in the hands of the Revolutionary Serbia, in order to ask Obradović to support his studies. Unfortunately, Obradović dismissed him. Disappointed, Karadžić left for Jadar and began working as a scribe for Jakov Nenadović. After the founding of the Belgrade Higher School, Karadžić became one of its first students.

Later life and death

Soon afterwards, he grew ill and left for medical treatment in Pest and Novi Sad, but was unable to receive treatment for his leg. It was rumored that Karadžić deliberately refused to undergo amputation, instead deciding to make do with a prosthetic wooden pegleg, of which there were several sarcastic references in some of his works. Karadžić returned to Serbia by 1810, and as unfit for military service, he served as the secretary for commanders Ćurčija and Hajduk-Veljko. His experiences would later give rise to two books. With the Ottoman defeat of the Serbian rebels in 1813, he left for Vienna and later met Jernej Kopitar, an experienced linguist with a strong interest in secular slavistics. Kopitar's influence helped Karadžić with his struggle in reforming the Serbian language and its orthography. Another important influence on his linguistic work was Sava Mrkalj.[11]

In 1814 and 1815, Karadžić published two volumes of Serbian Folk Songs, which afterwards increased to four, then to six, and finally to nine tomes. In enlarged editions, these admirable songs drew towards themselves the attention of all literary Europe and America. Goethe characterized some of them as "excellent and worthy of comparison with Solomon's Song of Songs."

In 1824, he sent a copy of his folksong collection to Jacob Grimm, who was enthralled particularly by The Building of Skadar which Karadžić recorded from singing of Old Rashko. Grimm translated it into German and the song was noted and admired for many generations to come.[12] Grimm compared them with the noblest flowers of Homeric poetry, and of The Building of Skadar he said: "one of the most touching poems of all nations and all times." The founders of the Romantic School in France, Charles Nodier, Prosper Mérimée, Lamartine, Gerard de Nerval, and Claude Fauriel translated a goodly number of them, and they also attracted the attention of Russian Alexander Pushkin, Finnish national poet Johan Ludwig Runeberg, Czech Samuel Roznay, Pole Kazimierz Brodzinski, English writers Walter Scott, Owen Meredith, and John Bowring, among others.

Karadžić continued collecting song well into the 1830s.[13] He arrived in Montenegro in the fall of 1834. Infirm, he descended to the Bay of Kotor to winter there, and returned in the spring of 1835. It was there that Karadžić met Vuk Vrčević, an aspiring littérateur, born in Risan. From then on Vrčević became Karadžić's faithful and loyal collaborator who collected folk songs and tales and sent them to his address in Vienna for many years to come.[14][15] Another equally diligent collaborator of Vuk Karadžić was another namesake from Boka Kotorska the Priest Vuk Popović. Both Vrčević and Popović were steadily and unselfishly involved in the gathering of the ethnographic, folklore and lexical material for Karadžić.[16] Later, other collaborators joined Karadžić, including Milan Đ. Milićević.

The majority of Karadžić's works were banned from publishing in Serbia and Austria during the rule of Prince Miloš Obrenović.[17] As observed from a political point of view, Obrenović saw the works of Karadžić as a potential hazard due to a number of apparent reasons, one of which was the possibility that the content of some of the works, although purely poetic in nature, was capable of creating a certain sense of patriotism and a desire for freedom and independence, which very likely might have driven the populace to take up arms against the Turks. This, in turn, would prove detrimental to Prince Miloš's politics toward the Ottoman Empire, with whom he had recently forged an uneasy peace. In Montenegro, however, Njegoš's printing press operated without the archaic letter known as the "hard sign". Prince Miloš was to resent Njegoš's abandonment of the hard sign, over which, at that time, furious intellectual battles were being waged, with ecclesiastical hierarchy involved as well. Karadžić's works, however, did receive high praise and recognition elsewhere, especially in Russian Empire. In addition to this, Karadžić was granted a full pension from the Emperor of All Russia in 1826.

He died in Vienna, and was survived by his daughter Mina Karadžić, who was a painter and writer, and by his son Dimitrije Karadžić, a military officer. His remains were relocated to Belgrade in 1897 and buried with great honours next to the grave of Dositej Obradović, in front of St. Michael's Cathedral (Belgrade).[18]

Work

Linguistic reforms

Karadžić reformed the Serbian literary language and standardised the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet by following strict phonemic principles on the Johann Christoph Adelung' model and Jan Hus' Czech alphabet. Karadžić's reforms of the Serbian literary language modernized it and distanced it from Serbian and Russian Church Slavonic and brought it closer to common folk speech. Because in Serbian written language of the early 19th century exist many words connected with the Orthodox church and large number of words from the Russian church language, Karadžić's proposal was to abandon this written language and to create a new one specifically, dialect of Eastern Herzegovina which he spoke. For the Serbian clergy with a base in the area around modern Novi Sad, grammar and vocabulary of Eastern Herzegovinian dialect was almost a foreign tongue and clergy could not take seriously Karadžić's insistence that basis for the new language be Eastern Herzegovinian dialect.[19] Karadžić was, together with Đuro Daničić, the main Serbian signatory to the Vienna Literary Agreement of 1850 which, encouraged by Austrian authorities, laid the foundation for the Serbo-Croatian language; Karadžić himself only ever referred to the language as "Serbian". Karadžić also translated the New Testament into Serbian, which was published in 1847. The Vukovian effort of language standardization lasted the remainder of the century. Before then the Serbs had achieved a fully independent state (1878), and a flourishing national culture based in Belgrade and Novi Sad. Despite the Vienna agreement, the Serbs had by this time developed an Ekavian pronunciation, which was the native speech of their two cultural capitals as well as the great majority of the Serbian population.

Karadžić held the view that all South Slavs that speak the Shtokavian dialect were Serbs or of Serbian origin and considered all of them to speak the Serbian language, which is today a matter of dispute among scientists.[20][21][22] However, Karadžić wrote later that he gave up this view because he saw that the Croats of his time did not agree with it, and he switched to the definition of the Serbian nation based on Orthodoxy and the Croatian nation based on Catholicism.[23]

Literature

In addition to his linguistic reforms, Karadžić also contributed to folk literature, using peasant culture as the foundation. Because of his peasant upbringing, he closely associated with the oral literature of the peasants, compiling it to use in his collection of folk songs, tales, and proverbs.[24] While Karadžić hardly considered peasant life romantic, he regarded it as an integral part of Serbian culture. He collected several volumes of folk prose and poetry, including a book of over 100 lyrical and epic songs learned as a child and written down from memory. He also published the first dictionary of vernacular Serbian. For his work he received little financial aid, at times living in poverty, though in the very last 9 years he did receive a pension from prince Miloš Obrenović.[25] In some cases Karadžić hid the fact that he had not only collected folk poetry by recording the oral literature but transcribed it from manuscript songbooks of other collectors from Srem.[26] His work had a chief role in establishing the importance of Kosovo in Serbian national identity and history.[27]

Non-philological work

Besides his greatest achievement on literary field, Karadžić gave his contribution to Serbian anthropology in combination with the ethnography of that time. He left notes on physical aspects of the human body alongside his ethnographic notes. He introduced a rich terminology on body parts (from head to toes) into the literary language. It should be mentioned that these terms are still used, both in science and everyday speech. He gave, among other things, his own interpretation of the connection between environment and inhabitants, with parts on nourishment, living conditions, hygiene, diseases and funeral customs. All in all this considerable contribution of Vuk Karadžić is not that famous or studied.

Recognition and legacy

Literary historian Jovan Deretić summarized his work as "During his fifty years of tireless activity, he accomplished as much as an entire academy of sciences."[28]

Karadžić was honored across Europe. He was chosen as a member of various European learned societies, including the Imperial Academy of Sciences in Vienna, Prussian Academy of Sciences and Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences.[29] He received several honorary doctorates.[30] and was decorated by Russian and Austro-Hungarian monarchs, Prussian king,[31] Order of Prince Danilo I[32] and Russian academy of science. UNESCO has proclaimed 1987 the year of Vuk Karadzić.[33] Karadžić was also elected an honorary citizen of the city of Zagreb.[34]

On the 100th anniversary of Karadžić's death (in 1964) student work brigades on youth action "Tršić 64" raised an amphitheater with a stage that was needed for organizing the Vukov sabor, and students' Vukov sabor. In 1987 Tršić received a comprehensive overhaul as a cultural-historical monument. Also, the road from Karadžić's home to Tronoša monastery was built. Karadžić's birth house was declared Monument of Culture of Exceptional Importance in 1979, and it is protected by Republic of Serbia.[35] Recently, rural tourism has become popular in Tršić, with many families converting their houses into buildings designed to accommodate guests. TV series based on his life were broadcast on Radio Television of Serbia. His portrait is often seen in Serbian schools. Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Serbia and Montenegro awarded a state Order of Vuk Karadžić.[36]

Vuk's Foundation maintains the legacy of Vuk Stefanović Karadžić in Serbia and Serb diaspora as well.[37][38] A student of primary (age six or seven to fourteen or fifteen) or secondary (age fourteen or fifteen to eighteen or nineteen) school in Serbia, that is awarded best grades for all subjects at the end of a school year, for each year in turn, is awarded at the end of his final year a "Vuk Karadžić diploma" and is known (in common speech) as "Vukovac", a name given to a member of an elite group of the highest performing students.[39]

Selected works

- Mala prostonarodna slaveno-serbska pesnarica, Vienna, 1814

- Pismenica serbskoga jezika, Vienna, 1814

- Narodna srbska pjesnarica II, Vienna, 1815

- Srpski rječnik istolkovan njemačkim i latinskim riječma (Serbian Dictionary, paralleled with German and Latin words), Vienna, 1818

- Narodne srpske pripovjetke, Vienna, 1821, supplemented edition, 1853

- Narodne srpske pjesme I-V, Vienna and Leipzig, 1823-1864

- Luke Milovanova Opit nastavlenja k Srbskoj sličnorečnosti i slogomjerju ili prosodii, Vienna, 1823

- Mala srpska gramatika, Leipzig, 1824

- Žizni i podvigi Knjaza Miloša Obrenovića, Saint Petersburg, 1825

- Danica I-V, Vienna, 1826-1834

- Žitije Đorđa Arsenijevića, Emanuela, Buda, 1827

- Miloš Obrenović, knjaz Srbije ili gradja za srpsku istoriju našega vremena, Buda, 1828

- Narodne srpske poslovice i druge različne, kao i one u običaj uzete riječi, Cetinje, 1836

- Montenegro und die Montenegriner: ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der europäischen Türkei und des serbischen Volkes, Stuttgart and Tübingen, 1837[40]

- Pisma Platonu Atanackoviću, Vienna, 1845

- Kovčežić za istoriju, jezik i običaje Srba sva tri zakona, Vienna, 1849

- Primeri Srpsko-slovenskog jezika, Vienna, 1857

- Praviteljstvujušči sovjet serbski za vremena Kara-Đorđijeva, Vienna, 1860

- Srpske narodne pjesme iz Hercegovine, Vienna, 1866

- Život i običaji naroda srpskog, Vienna, 1867

- Nemačko srpski rečnik, Vienna, 1872

Translations:

- New Testament, Vienna, 1847

Misquotes

Write as you speak and read as it is written.

— The essence of modern Serbian spelling

Although the above quotation is often attributed to Vuk Stefanović Karadžić in Serbia, it is in fact an orthographic principle devised by the German grammarian and philologist Johann Christoph Adelung.[41] Karadžić merely used that principle to push through his language reform.[42] The attribution of the quote to Karadžić is a common misconception in Serbia, Montenegro and the rest of former Yugoslavia. Due to that fact, the entrance exam to the University of Belgrade Faculty of Philology occasionally contains a question on the authorship of the quote (as a sort of trick question).

See also

People closely related to Karadžić's work

References

- Szajkowski, Bogdan (1993). Encyclopaedia of Conflicts, Disputes, and Flashpoints in Eastern Europe, Russia, and the Successor States. Harlow, UK: Longman. p. 134. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- Wintle, Michael J. (2008). Imagining Europe Europe and European Civilisation as Seen from its Margins and by the Rest of the World, in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Brussels: Peter Lang. p. 114. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- Jones, Derek (2001). Censorship: A World Encyclopedia. London: Fitzroy Dearborn. p. 1315.

- Đorđević, Kristina. "Jezička reforma Vuka Karadžića i stvaranje srpskog književnog jezika.pdf" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Vuk Stefanović Karadžić | Serbian language scholar". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-12-05.

- Selvelli, Giustina. "The Cultural Collaboration between Jacob Grimm and Vuk Karadžić. A fruitful Friendship Connecting Western Europe to the Balkans". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Selvelli, Giustina. "The Cultural Collaboration between Jacob Grimm and Vuk Karadžić. A fruitful Friendship Connecting Western Europe to the Balkans". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Vuk Stefanović Karadžić Biografija". Biografija.org (in Serbian). 2018-04-19. Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- "Историја | Sremski Karlovci" (in Serbian). Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- "Koreni obrazovanja u Srbiji". Nedeljnik Vreme. Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- Đorđević, Kristina. "Jezička reforma Vuka Karadžića i stvaranje srpskog književnog jezika.pdf" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Alan Dundes (1996). The Walled-Up Wife: A Casebook. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-0-299-15073-0.

- Sremac, Radovan. "Vuk St. Karadžić i Šiđani (Sremske novine br. 2915 od 11.1.2017)". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Vuk Karadzic - Vuk Vrcevic, Srpske narodne pjesme iz Hercegovine". Scribd. Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- ПАТриот (2017-12-08). "Вук Караџић препродао стотине старих српских књига странцима". Патриот (in Serbian). Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- ПАТриот (2017-12-08). "Вук Караџић препродао стотине старих српских књига странцима". Патриот (in Serbian). Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- Kostić, Jelena (2018-04-11). "Vuk Stefanović Karadžić – Reformator Srpskog Jezika I Velikan Srpske Književnosti | Jelena Kostić". Svet nauke. Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- "Vuk Stefanovic Karadzic". www.loznica.rs. Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- Ronelle Alexander, 2006, Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian, a Grammar: With Sociolinguistic Commentary, https://books.google.hr/books/about/Bosnian_Croatian_Serbian_a_Grammar.html?id=6HTdZ5rxJ-cC&redir_esc=y #page=382-383

- Kovačević, Dr Miloš. "O jednakosti srpskoga jezika". Politika Online. Retrieved 2019-05-01.

- Danijela Nadj. "Vuk Karadzic, Serbs All and Everywhere (1849)". Hic.hr. Retrieved 2010-08-04.

- Stehlík, Petr. "Slovački apostol jugoslavenstva: Bogoslav Šulek i njegova polemika s Vukom Karadžićem / Slovak Apostle of Yugoslavism: Bogoslav Šulek and His Polemic Against Vuk Karadžić". Bogoslav Šulek i njegov filološki rad.

- Kilian, Ernst (1995). "Die Wiedergeburt Kroatiens aus dem Geist der Sprache" [The rebirth of Croatia from the spirit of the language]. In Budak, Neven (ed.). Kroatien: Landeskunde – Geschichte – Kultur – Politik – Wirtschaft – Recht (in German). Wien. p. 380. ISBN 9783205984962.

- Sudimac, Nina; Stojković, Jelena S. "SYNTAX OF VERB FORMS IN SERBIAN FOLK PROVERBS BY VUK STEFANOVIĆ KARADŽIĆ". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Antić, Dragan (2017-09-06). "Životni put Vuka Karadžića po godinama (Biografija)". Moje dete (in Serbian). Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- Prilozi za književnost, jezik, istoriju i folklor (in Serbian). Државна штампарија Краљевине Срба, Хрвата и Словенаца. 1965. p. 264. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

- Selvelli, Giustina. "The Cultural Collaboration between Jacob Grimm and Vuk Karadžić. A fruitful Friendship Connecting Western Europe to the Balkans". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Stephen K. Batalden; Kathleen Cann; John Dean (2004). Sowing the Word: The Cultural Impact of the British and Foreign Bible Society, 1804-2004. Sheffield Phoenix Press. pp. 253–. ISBN 978-1-905048-08-3.

- "Serbia.com - Vuk Karadzic". www.serbia.com. Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- Riznica srpska — Vuk i jezik

- "Serbia.com - Vuk Karadzic". www.serbia.com. Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- Acović, Dragomir (2012). Slava i čast: Odlikovanja među Srbima, Srbi među odlikovanjima. Belgrade: Službeni Glasnik. p. 85.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kostić, Jelena (2018-04-11). "Vuk Stefanović Karadžić – Reformator Srpskog Jezika I Velikan Srpske Književnosti | Jelena Kostić". Svet nauke. Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- Milutinović, Zoran (2011). "Review of the Book Jezik i nacionalizam" (PDF). The Slavonic and East European Review. 89 (3): 520–524. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- "Споменици културе у Србији". spomenicikulture.mi.sanu.ac.rs. Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- "Država bez odlikovanja". Politika Online. Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- "Vukova zaduzbina". www.loznica.rs. Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- Spasić, Ivana; Subotić, Milan (2001). Revolution and Order: Serbia After October 2000. IFDT. ISBN 9788682417033.

- "Правилник-о-дипломама-за-изузетан-успех-ученика-у-основној-школи" (PDF).

- Stefanović-Karadžić, Vuk (1837). Montenegro und die Montenegriner: Ein Beitrag zur Kenntniss der europäischen Türkei und des serbischen Volkes. Stuttgart und Tübingen: Verlag der J. G. Cotta'schen Buchhandlung.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Đorđević, Kristina. "Jezička reforma Vuka Karadžića i stvaranje srpskog književnog jezika.pdf" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - as stated in the book The Grammar of the Serbian Language by Ljubomir Popović

Further reading

- Kulakovski, Platon (1882). Vuk Karadžić njegov rad i značaj. Moscow: Prosveta.

- Lockwood, Yvonne R. 1971. Vuk Stefanović Karadžić: Pioneer and Continuing Inspiration of Yugoslav Folkloristics. Western Folklore 30.1: pp. 19–32.

- Popović, Miodrag (1964). Vuk Stefanović Karadžić. Belgrade: Nolit.

- Skerlić, Jovan, Istorija Nove Srpske Književnosti/History of New Serbian Literature (Belgrade, 1914, 1921) pages 239-276.

- Stojanović, Ljubomir (1924). Život i rad Vuka Stefanovića Karadžića. Belgrade: BIGZ.

- Vuk, Karadzic. Works, book XVIII, Belgrade 1972.

- Wilson, Duncan (1970). The Life and Times of Vuk Stefanović Karadzić, 1787-1864; Literacy, Literature and National Independence in Serbia. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-821480-4.

External links

| Look up Vukovian in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vuk Karadžić. |

- Mijatovich, Chedomille (1911). "Karajich, Vuk Stefanovich". Encyclopædia Britannica. 15 (11th ed.). pp. 674–675.

- Biography (in Serbian)

- Encyclopedia of World Biography from Bookrags.com (in English)

- Works by Vuk Karadžić at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Vuk Karadžić at Internet Archive

- Vuk's Foundation (in Serbian)

- Vuk Karadžić online library at Project Rastko (in Serbian)

- Jernej Kopitar as a strategist of Karadžić’s reform of the literary language PDF (in Serbian)