Selma Lagerlöf

Selma Ottilia Lovisa Lagerlöf (/ˈlɑːɡərlɜːf/, also US: /-lʌv, -ləv/,[1][2] Swedish: [ˈsɛ̂lːma ˈlɑ̂ːɡɛˌɭøːv] (![]()

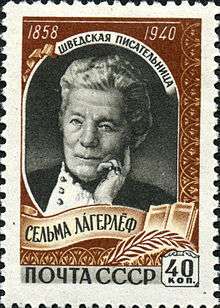

Selma Lagerlöf | |

|---|---|

Lagerlöf in 1909 | |

| Born | Selma Ottilia Lovisa Lagerlöf 20 November 1858 Mårbacka, Värmland, Sweden |

| Died | 16 March 1940 (aged 81) Mårbacka, Värmland, Sweden |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Nationality | Swedish |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Literature 1909 |

Early life

Born at Mårbacka[4] (now in Sunne Municipality), an estate in Värmland in western Sweden, Lagerlöf was the daughter of Erik Gustaf Lagerlöf, a lieutenant in the Royal Värmland Regiment, and Louise Lagerlöf (née Wallroth), whose father was a well-to-do merchant and a foundry owner (brukspatron).[5] Lagerlöf was the couple's fifth child out of six. She was born with a hip injury, which was caused by detachment in the hip joint. At the age of three and a half, a sickness left her lame in both legs, although she later recovered.

She was a quiet child, more serious than others her age, with a deep love for reading. She was constantly writing poetry as a child, but did not publish anything officially until later in life. Her grandmother helped raise her, often telling stories of fairytales and fantasy. Growing up, she was plain and slightly lame, and an account stated that the cross-country wanderings of the majoress and Elisabet in The Saga of Gosta Berling could be the author's compensatory fantasies.[5]

As many other children of the upper class, the children of the family received their education at home, since the Volksschule system, compulsory education system, was not fully developed yet. Their teacher thus came to Mårbacka and the children received education in English, as well as French. Selma finished reading her first novel at the age of seven. The novel was Osceola by Thomas Mayne Reid. After completing the novel, Selma is said to have decided on becoming an author when she grew up.[6]

In 1868, at the age of 10, Selma completed reading the Bible. At this time her father was very ill, and she hoped that God would heal her father if she read the Bible from cover to cover. Her father lived for another 17 years. In this manner, Selma Lagerlöf became accustomed to the language of Scripture from an early age.

The sale of Mårbacka following her father's illness in 1884 had a serious impact on her development. Selma's father is said to have been an alcoholic, something she rarely discussed.[7] Her father did not want Selma to continue her education or remain involved with the women's movement. Later in life, she would buy back her father's estate with the money she received for her Nobel Prize.[8] Lagerlöf lived there for the rest of her life.[9] She also completed her studies at the Royal Seminary to become a teacher the same year as her father died.

Career

Lagerlöf was educated at the Högre lärarinneseminariet in Stockholm from 1882 to 1885. She worked as a country schoolteacher at a high school for girls in Landskrona from 1885 to 1895,[10] while honing her story-telling skills, with particular focus on the legends she had learned as a child. She liked the teaching profession and appreciated her students. She had a talent for capturing the children's attention through telling them stories about the different countries about which they were studying or stories about Jesus and his disciples. During this period of her life, Selma lived with her aunt Lovisa Lagerlöf.

Through her studies at the Royal Women's Superior Training Academy in Stockholm, Lagerlöf reacted against the realism of contemporary Swedish-language writers such as August Strindberg. She began her first novel, Gösta Berling's Saga, while working as a teacher in Landskrona. Her first break as a writer came when she submitted the first chapters to a literary contest in the magazine Idun, and won a publishing contract for the whole book. At first, her writing only received mild reviews from critics. Once a popular male critic, Georg Brandes, gave her positive reviews of the Danish translation, her popularity soared.[11] She received financial support of Fredrika Limnell, who wished to enable her to concentrate on her writing.[12]

In 1894, she met the Swedish writer Sophie Elkan, who became her friend and companion.[13] Over many years, Elkan and Lagerlöf critiqued each other's work. Lagerlöf wrote that Elkan strongly influenced her work and that she often disagreed sharply with the direction Lagerlöf wanted to take in her books. Selma's letters to Sophie were published in 1993, titled Du lär mig att bli fri (You Teach me to be Free).[11]

A visit in 1900 to the American Colony in Jerusalem became the inspiration for Lagerlöf's book by that name.[14] The royal family and the Swedish Academy gave her substantial financial support to continue her passion.[15] Jerusalem was also acclaimed by critics, who began comparing her to Homer and Shakespeare, so that she became a popular figure both in Sweden and abroad.[3] By 1895, she gave up her teaching to devote herself to her writing. With the help of proceeds from Gösta Berlings Saga and a scholarship and grant, she made two journeys, which were largely instrumental in providing material for her next novel. With Elkan, she traveled to Italy, and she also traveled to Palestine and other parts of the East.[16] In Italy, a legend of a Christ Child figure that had been replaced with a false version inspired Lagerlöf's novel Antikrists mirakler (The Miracles of the Antichrist). Set in Sicily, the novel explores the interplay between Christian and socialist moral systems. However, most of Lagerlöf's stories were set in Värmland.

In 1902, Lagerlöf was asked by the National Teacher's Association to write a geography book for children. She wrote Nils Holgerssons underbara resa genom Sverige (The Wonderful Adventures of Nils), a novel about a boy from the southernmost part of Sweden, who had been shrunk to the size of a thumb and who travelled on the back of a goose across the country. Lagerlöf mixed historical and geographical facts about the provinces of Sweden with the tale of the boy's adventures until he managed to return home and was restored to his normal size.[7] The novel is one of Lagerlöf's most well-known books, and it has been translated into more than 30 languages.[17]

She moved in 1897 to Falun, and met Valborg Olander, who became her literary assistant and friend, but Elkan's jealousy of Olander was a complication in the relationship. Olander, a teacher, was also active in the growing women's suffrage movement in Sweden. Selma Lagerlöf herself was active as a speaker for the National Association for Women's Suffrage, which was beneficial for the organisation because of the great respect which surrounded Lagerlöf, and she spoke at the International Suffrage Congress in Stockholm in June 1911, where she gave the opening address, as well as at the victory party of the Swedish suffrage movement after women suffrage had been granted in May 1919.[18]

Selma Lagerlöf was a friend of the German-Jewish writer Nelly Sachs. Shortly before her death in 1940, Lagerlöf intervened with the Swedish royal family to secure the release of Sachs and Sachs' aged mother from Nazi Germany, on the last flight from Germany to Sweden, and their lifelong asylum in Stockholm.

Literary adaptations

In 1919, Lagerlöf sold all the movie rights to all of her as-yet unpublished works to Swedish Cinema Theatre (Swedish: Svenska Biografteatern), so over the years, many movie versions of her works were made. During the era of Swedish silent cinema, her works were used in film by Victor Sjöström, Mauritz Stiller, and other Swedish film makers.[19] Sjöström's retelling of Lagerlöf's tales about rural Swedish life, in which his camera recorded the detail of traditional village life and the Swedish landscape, provided the basis of some of the most poetic and memorable products of silent cinema. Jerusalem was adapted in 1996 into an internationally acclaimed film Jerusalem.

Awards and commemoration

On 10 December 1909,[20] Selma Lagerlöf won the Nobel Prize "in appreciation of the lofty idealism, vivid imagination, and spiritual perception that characterize her writings",[21] but the decision was preceded by harsh internal power struggle within the Swedish Academy, the body that awards the Nobel Prize in literature.[22] During her acceptance speech, she remained humble and told a fantastic story of her father, as she visited him in heaven. In the story, she asks her father for help with the debt she owes and her father explains the debt is from all the people who supported her throughout her career.[7] In 1904, the Academy had awarded her its great gold medal, and in 1914, she also became a member of the academy. For both the academy membership and her Nobel literature prize, she was the first woman to be so honored.[10] In 1991, she became the first woman to be depicted on a Swedish banknote, when the first 20-kronor note was released.[23]

In 1907, she received the degree of doctor of letters from Uppsala University.[10] In 1928, she received an honorary doctorate from the University of Greifswald's Faculty of Arts. At the start of World War II, she sent her Nobel Prize medal and gold medal from the Swedish Academy to the government of Finland to help raise money to fight the Soviet Union.[24] The Finnish government was so touched that it raised the necessary money by other means and returned her medal to her.

Two hotels are named after her in Östra Ämtervik in Sunne, and her home, Mårbacka, is preserved as a museum.

One of her stories, "The Rattrap", was included as a part of the Indian curriculum, for the students of class 12 CBSE in their Flamingo textbook.

Bibliography

Works by Selma Lagerlöf

Original Swedish-language publications are listed primarily.[25][26]

The vogue for Lagerlöf in the United States was due in part to Velma Swanston Howard, or V.S. Howard (1868–1937, a suffragette and Christian scientist)[27] – who was an early believer in her appeal to Americans and who carefully translated many of her books.[10]

- Gösta Berlings saga (1891; novel). Translated as The Story of Gösta Berling (Pauline Bancroft Flach, 1898), Gösta Berling's Saga (V.S. Howard and Lillie Tudeer, 1898), The Story of Gösta Berling (R. Bly, 1962)

- Osynliga länkar (1894; short stories). Translated as Invisible Links (Pauline Bancroft Flach, (1869–1966) 1899)

- Antikrists mirakler (1897; novel). Translated as The Miracles of Antichrist (Selma Ahlström Trotz, 1899) and The Miracles of Antichrist (Pauline Bancroft Flach (1869–1966), 1899)

- Drottningar i Kungahälla (1899; short stories). Translated as The Queens of Kungahälla and Other Sketches From a Swedish Homestead (Jessie Bröchner, 1901; C. Field, 1917)

- En herrgårdssägen (1899; short stories). Translated as The Tale of a Manor and Other Sketches (C. Field, 1922)

- Jerusalem : två berättelser. 1, I Dalarne (1901; novel). Translated as Jerusalem (Jessie Bröchner, 1903; V.S. Howard, 1914)

- Jerusalem : två berättelser. 2, I det heliga landet (1902; novel). Translated as The Holy City : Jerusalem II (V.S. Howard, 1918)

- Herr Arnes penningar (1903; novel). Translated as Herr Arne's Hoard (Arthur G. Chater, 1923; Philip Brakenridge, 1952) and The Treasure (Arthur G. Chater, 1925) – adapted as the 1919 film Sir Arne's Treasure.

- Kristuslegender (1904; short stories). Translated as Christ Legends and Other Stories (V,S. Howard, 1908)

- Nils Holgerssons underbara resa genom Sverige (1906–07; novel). Translated as The Wonderful Adventures of Nils (V.S. Howard, 1907; Richard E. Oldenburg, 1967) and Further Adventures of Nils (V.S. Howard, 1911)

- En saga om en saga och andra sagor (1908; short stories). Translated as The Girl from the Marsh Croft (V.S. Howard, 1910) and Girl from the Marsh Croft and Other Stories (edited by Greta Anderson, 1996)

- Hem och stat: Föredrag vid rösträttskongressen den 13 juni 1911 (1911; non-fiction). Translated as Home and State: Being an Address Delivered at Stockholm at the Sixth Convention of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance, June 1911 (C. Ursula Holmstedt, 1912)

- Liljecronas hem (1911; novel). Translated as Liliecrona's Home (Anna Barwell, 1913)

- Körkarlen (1912; novel). Translated as Thy Soul Shall Bear Witness! (William Frederick Harvey, 1921). Filmed as The Phantom Carriage, The Phantom Chariot, The Stroke of Midnight.

- Stormyrtossen: Folkskädespel i 4 akter (1913) with Bernt Fredgren

- Astrid och andra berättelser (1914; short stories)

- Kejsarn av Portugallien (1914; novel). Translated as The Emperor of Portugallia (V.S. Howard, 1916)

- Dunungen: Lustspel i fyra akter (1914; play)

- Silvergruvan och andra berättelser (1915; short stories)

- Troll och Människor (1915, 1921; novel). Translated as The Changeling (Lagerlöf novel) (Susanna Stevens, 1992)

- Bannlyst (1918; novel). Translated as The Outcast (Lagerlöf novel) (W. Worster, 1920/22)

- Kavaljersnoveller (1918; novel)

- Zachris Topelius utveckling och mognad (1920; non-fiction), biography of Zachris Topelius

- Mårbacka (1922; memoir). Translated as Marbacka: The Story of a Manor (V.S. Howard, 1924) and Memories of Marbacka (Greta Andersen, 1996) – named for the estate Mårbacka where Lagerlöf was born and raised

- The Ring trilogy – published in 1931 as The Ring of the Löwenskölds, containing the Martin and Howard translations, LCCN 31-985

- Löwensköldska ringen (1925; novel). Translated as The General's Ring (Francesca Martin, 1928) and as The Löwensköld Ring (Linda Schenck, 1991)

- Charlotte Löwensköld (1925; novel). Translated as Charlotte Löwensköld (V.S. Howard)

- Anna Svärd (1928; novel). Translated as Anna Svärd (V.S. Howard, 1931)

- En Herrgårdssägen: Skådespel i fyra akter (1929; play), based on 1899 work En herrgårdssägen

- Mors porträtt och andra berättelser (1930; short stories)

- Ett barns memoarer: Mårbacka (1930; memoir). Translated as Memories of My Childhood (Lagerlöf) Further Years at Mårbacka (V.S. Howard, 1934)

- Dagbok för Selma Ottilia Lovisa Lagerlöf (1932; memoir). Translated as The Diary of Selma Lagerlöf (V.S. Howard, 1936)

- Höst (1933; short stories). Translated as Harvest (book) (Florence and Naboth Hedin, 1935)

- Julberättelser (1936)

- Gösta Berlings saga: Skådespel i fyra akter med prolog och epilog effer romanen med samma namn (1936)

- Från skilda tider: Efterlämnade skrifter (1943–45)

- Dockteaterspel (1959)

- Madame de Castro: En ungdomsdikt (1984)

Works about Selma Lagerlöf

- Berendsohn, Walter A., Selma Lagerlöf: Her Life and Work (adapted from the German by George F. Timpson) – London : Nicholson & Watson, 1931

- Wägner, Elin, Selma Lagerlöf I (1942) and Selma Lagerlöf II (1943)[28]

- Vrieze, Folkerdina Stientje de, Fact and Fiction in the Autobiographical Works of Selma Lagerlof – Assen, Netherlands : Van Gorcum, 1958

- Nelson, Anne Theodora, The Critical Reception of Selma Lagerlöf in France – Evanston, Ill., 1962

- Olson-Buckner, Elsa, The epic tradition in Gösta Berlings saga – Brooklyn, N.Y. : Theodore Gaus, 1978

- Edström, Vivi, Selma Lagerlöf (trans. by Barbara Lide) – Boston : Twayne Publishers, 1984

- Madler, Jennifer Lynn, The Literary Response of German-language Authors to Selma Lagerlöf – Urbana, Ill. : University of Illinois, 1998

- De Noma, Elizabeth Ann, Multiple Melodrama: the Making and Remaking of Three Selma Lagerlöf Narratives in the Silent Era and the 1940s – Ann Arbor, Mich. : UMI Research Press, cop. 2000

- Watson, Jennifer, Swedish Novelist Selma Lagerlöf, 1858–1940, and Germany at the Turn of the Century: O du Stern ob meinem Garten – Lewiston, NY : Edwin Mellen Press, 2004

- Robert Aldrich; Garry Wotherspoon, eds. (2002). Who's Who in Gay and Lesbian History from Antiquity to World War II 2nd ed. Routledge; London. ISBN 0-415-15983-0.

See also

References

- "Lagerlöf". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "Lagerlöf, Selma" (US) and "Lagerlöf, Selma". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- Forsas-Scott, Helena (1997). Swedish Women's Writing 1850-1995. London: The Athlone Press. p. 63. ISBN 0485910039.

- H. G. L. (1916), "Miss Lagerlöf at Marbacka", in Henry Goddard Leach (ed.), The American-Scandinavian review, 4, American-Scandinavian Foundation, p. 36

- Lagerlof, Selma; Schoolfield, George (2009). The Saga of Gosta Berling. New York: Penguin Classics. ISBN 9781101140482.

- "Selma Lagerlöf – författaren". www.marbacka.com. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- "Selma Lagerlöf: Surface and Depth". The Public Domain Review. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- "Selma Lagerlof | Swedish author". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- "Selma Lagerlöf - Facts - NobelPrize.org". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- "Selma Ottiliana Lovisa Lagerlöf (1858–1940)". authorscalendar.info. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- Lagerlof, Selma (2013). The Selma Lagerlof Megapack: 31 Classic Novels and Stories. Rockville: Wildside Press LLC. p. 20. ISBN 9781434443441.

- Munck, Kerstin (2002), "Lagerlöf, Selma", glbtq.com, archived from the original on 16 November 2007

- Zaun-Goshen, Heike (2002), Times of Change, archived from the original on 17 June 2010

- "Selma Lagerlöf – Biographical". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

-

- "100 år med Nils Holgersson" (PDF). Lund University Library. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- Hedwall, Barbro (2011). Susanna Eriksson Lundqvist. red. Vår rättmätiga plats. Om kvinnornas kamp för rösträtt. (Our Rightful Place. About women's struggle for suffrage) Förlag Bonnier. ISBN 978-91-7424-119-8 (Swedish)

- Furhammar, Leif (2010), "Selma Lagerlöf and Literary Adaptations", Mariah Larsson and Anders Marklund (eds), "Swedish Film: An Introduction and Reader", Lund: Nordic Academic Press, pp. 86–91.

- Lagerlöf, Selma (10 December 1909). "Banquet Speech". Nobel Prize. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- "Literature 1909", NobelPrize.org, retrieved 6 March 2010

- "Våldsam debatt i Akademien när Lagerlöf valdes". Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). 25 September 2009.

- 20 Swedish Krona banknote 2008 Selma Lagerlöf. worldbanknotescoins.com (20 April 2015)

- Gunther, Ralph (2003), "The magic zone: sketches of the Nobel Laureates", Scripta Humanistica, 150, p. 36, ISBN 1-882528-40-9

- "Selma Lagerlöf – Bibliography", NobelPrize.org, retrieved 6 March 2010

- Liukkonen, Petri. "Selma Lagerlöf". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 26 January 2015.

- "Howard, Velma Swanston, 1868–1937". Library of Congress Authorities (lccn.loc.gov). Retrieved 2019-09-30.

- "Wägner, Elin". Nordic Women's Literature. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Selma Lagerlöf. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Selma Lagerlöf |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1922 Encyclopædia Britannica article about "Selma Lagerlöf". |

| Library resources about Selma Lagerlöf |

| By Selma Lagerlöf |

|---|

Resources

- Selma Lagerlöf on Nobelprize.org

- List of Works

- Petri Liukkonen. "Selma Lagerlöf". Books and Writers

- The background to the writing of The Wonderful Adventures of Nils

- Works by Selma Lagerlöf at Open Library

- Newspaper clippings about Selma Lagerlöf in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Selma Lagerlöf at Library of Congress Authorities, with 187 catalogue records

Works online

- Works by Selma Lagerlöf at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Selma Lagerlöf at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Selma Lagerlöf at Internet Archive

- Works by Selma Lagerlöf at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Selma Lagerlöf at Project Runeberg (In Swedish)

- Works by Selma Lagerlöf at Swedish Literature Bank (In Swedish)

| Cultural offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Albert Theodor Gellerstedt |

Swedish Academy, Seat No.7 1914–1940 |

Succeeded by Hjalmar Gullberg |