Serbian Cyrillic alphabet

The Serbian Cyrillic alphabet (Serbian: српска ћирилица/srpska ćirilica, pronounced [sr̩̂pskaː t͡ɕirǐlit͡sa]) is an adaptation of the Cyrillic script for Serbo-Croatian, developed in 1818 by Serbian linguist Vuk Karadžić. It is one of the two alphabets used to write standard modern Serbian, Bosnian and Montenegrin, the other being Latin.

| Serbian Cyrillic | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Languages | Serbo-Croatian (except Croatian) |

Time period | 1814 (modern) |

Parent systems | Greek alphabet (partly Glagolitic alphabet)

|

Child systems | Macedonian Montenegrin |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| ISO 15924 | Cyrl, 220 |

Unicode alias | Cyrillic |

Unicode range | subset of Cyrillic (U+0400...U+04F0) |

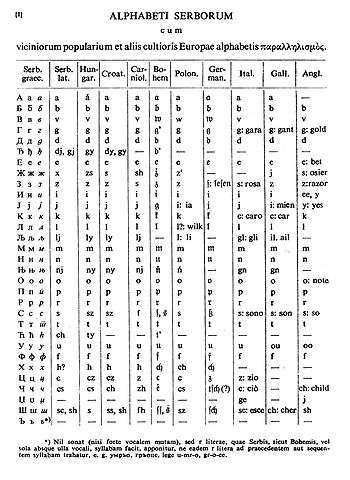

Karadžić based his alphabet on the previous "Slavonic-Serbian" script, following the principle of "write as you speak and read as it is written", removing obsolete letters and letters representing iotified vowels, introducing ⟨J⟩ from the Latin alphabet instead, and adding several consonant letters for sounds specific to Serbian phonology. During the same period, Croatian linguists led by Ljudevit Gaj adapted the Latin alphabet, in use in western South Slavic areas, using the same principles. As a result of this joint effort, Cyrillic and Latin alphabets for Serbo-Croatian have a complete one-to-one congruence, with the Latin digraphs Lj, Nj, and Dž counting as single letters.

Vuk's Cyrillic alphabet was officially adopted in Serbia in 1868, and was in exclusive use in the country up to the inter-war period. Both alphabets were co-official in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and later in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Due to the shared cultural area, Gaj's Latin alphabet saw a gradual adoption in Serbia since, and both scripts are used to write modern standard Serbian, Montenegrin and Bosnian; Croatian only uses the Latin alphabet. In Serbia, Cyrillic is seen as being more traditional, and has the official status (designated in the Constitution as the "official script", compared to Latin's status of "script in official use" designated by a lower-level act, for national minorities). It is also an official script in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Montenegro, along with Latin.

The Serbian Cyrillic alphabet was used as a basis for the Macedonian alphabet with the work of Krste Misirkov and Venko Markovski.

Official use

Cyrillic is in official use in Serbia, Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina.[1] Although the Bosnian language "officially accept[s] both alphabets",[1] the Latin script is almost always used in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina,[1] whereas Cyrillic is in everyday use in Republika Srpska[1].[2] The Serbian language in Croatia is officially recognized as a minority language, however, the use of Cyrillic in bilingual signs has sparked protests and vandalism.

Cyrillic is an important symbol of Serbian identity.[3] In Serbia, official documents are printed in Cyrillic only[4] even though, according to a 2014 survey, 47% of the Serbian population write in the Latin alphabet whereas 36% write in Cyrillic.[5]

Modern alphabet

The following table provides the upper and lower case forms of the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet, along with the equivalent forms in the Serbian Latin alphabet and the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) value for each letter:

|

|

Early history

Early Cyrillic

According to tradition, Glagolitic was invented by the Byzantine Christian missionaries and brothers Cyril and Methodius in the 860s, amid the Christianization of the Slavs. Glagolitic appears to be older, predating the introduction of Christianity, only formalized by Cyril and expanded to cover non-Greek sounds. Cyrillic was created by the orders of Boris I of Bulgaria by Cyril's disciples, perhaps at the Preslav Literary School in the 890s.[6]

The earliest form of Cyrillic was the ustav, based on Greek uncial script, augmented by ligatures and letters from the Glagolitic alphabet for consonants not found in Greek. There was no distinction between capital and lowercase letters. The literary Slavic language was based on the Bulgarian dialect of Thessaloniki.[6]

Medieval Serbian Cyrillic

Part of the Serbian literary heritage of the Middle Ages are works such as Vukan Gospels, St. Sava's Nomocanon, Dušan's Code, Munich Serbian Psalter, and others. The first printed book in Serbian was the Cetinje Octoechos (1494).

Karadžić's reform

Vuk Stefanović Karadžić fled Serbia during the Serbian Revolution in 1813, to Vienna. There he met Jernej Kopitar, a linguist with interest in slavistics. Kopitar and Sava Mrkalj helped Vuk to reform the Serbian language and its orthography. He finalized the alphabet in 1818 with the Serbian Dictionary.

Karadžić reformed the Serbian literary language and standardised the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet by following strict phonemic principles on the Johann Christoph Adelung' model and Jan Hus' Czech alphabet. Karadžić's reforms of the Serbian literary language modernised it and distanced it from Serbian and Russian Church Slavonic, instead bringing it closer to common folk speech, specifically, to the dialect of Eastern Herzegovina which he spoke. Karadžić was, together with Đuro Daničić, the main Serbian signatory to the Vienna Literary Agreement of 1850 which, encouraged by Austrian authorities, laid the foundation for the Serbian language, various forms of which are used by Serbs in Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia today. Karadžić also translated the New Testament into Serbian, which was published in 1868.

He wrote several books; Mala prostonarodna slaveno-serbska pesnarica and Pismenica serbskoga jezika in 1814, and two more in 1815 and 1818, all with the alphabet still in progress. In his letters from 1815-1818 he used: Ю, Я, Ы and Ѳ. In his 1815 song book he dropped the Ѣ.[7]

The alphabet was officially adopted in 1868, four years after his death.[8]

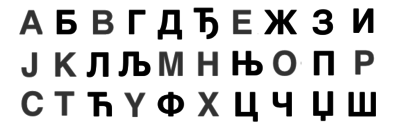

From the Old Slavic script Vuk retained these 24 letters:

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ж ж | З з |

| И и | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р |

| С с | Т т | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш |

He added one Latin letter:

| Ј ј |

And 5 new ones:

| Љ љ | Њ њ | Ћ ћ | Ђ ђ | Џ џ |

He removed:

| Ѥ ѥ (је) | Ѣ, ѣ (јат) | І ї (и) | Ѵ ѵ (и) | Ѹ ѹ (у) | Ѡ ѡ (о) | Ѧ ѧ (мали јус) | Ѫ ѫ (велики јус) | Ы ы (јери, тврдо и) | |

| Ю ю (ју) | Ѿ ѿ (от) | Ѳ ѳ (т) | Ѕ ѕ (дз) | Щ щ (шт) | Ѯ ѯ (кс) | Ѱ ѱ (пс) | Ъ ъ (тврди полуглас) | Ь ь (меки полуглас) | Я я (ја) |

Modern history

Austria-Hungary

Orders issued on the 3 and 13 October 1914 banned the use of Serbian Cyrillic in the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia, limiting it for use in religious instruction. A decree was passed on January 3, 1915, that banned Serbian Cyrillic completely from public use. An imperial order in October 25, 1915, banned the use of Serbian Cyrillic in the Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina, except "within the scope of Serb Orthodox Church authorities".[9][10]

World War II

In 1941, the Nazi puppet Independent State of Croatia banned the use of Cyrillic,[11] having regulated it on 25 April 1941,[12] and in June 1941 began eliminating "Eastern" (Serbian) words from the Croatian language, and shut down Serbian schools.[13][14]

Yugoslavia

The Serbian Cyrillic script was one of the two official scripts used to write the Serbo-Croatian language in Yugoslavia since its establishment in 1918, the other being Latin script (latinica).

Following the breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, Serbian Cyrillic is no longer used in Croatia on national level, while in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro it remained an official script.[15]

Contemporary period

Under the Constitution of Serbia of 2006, Cyrillic script is the only one in official use.[16]

Special letters

The ligatures ⟨Љ⟩ and ⟨Њ⟩, together with ⟨Џ⟩, ⟨Ђ⟩ and ⟨Ћ⟩ were developed specially for the Serbian alphabet.

- Karadžić based the letters ⟨Љ⟩ and ⟨Њ⟩ on a design by Sava Mrkalj, combining the letters ⟨Л⟩ (L) and ⟨Н⟩ (N) with the soft sign (Ь).

- Karadžić based ⟨Џ⟩ on letter "Gea" in the Romanian Cyrillic alphabet.

- ⟨Ћ⟩ was adopted by Karadžić to represent the voiceless alveolo-palatal affricate (IPA: /tɕ/). The letter was based on, but different in appearance to, the letter Djerv, which is the 12th letter of the Glagolitic alphabet; that letter had been used in written Serbian since the 12th century, to represent /ɡʲ/, dʲ/ and /dʑ/.

- Karadžić adopted a design by Lukijan Mušicki for the letter ⟨Ђ⟩. It was based on the letter ⟨Ћ⟩, as adapted by Karadžić.

- ⟨Ј⟩ was adopted from the Latin alphabet.

⟨Љ⟩, ⟨Њ⟩ and ⟨Џ⟩ were later adopted for use in the Macedonian alphabet.

Differences from other Cyrillic alphabets

Serbian Cyrillic does not use several letters encountered in other Slavic Cyrillic alphabets. It does not use hard sign (ъ) and soft sign (ь), but the aforementioned soft-sign ligatures instead. It does not have Russian/Belarusian Э, the semi-vowels Й or Ў, nor the iotated letters Я (Russian/Bulgarian ya), Є (Ukrainian ye), Ї (yi), Ё (Russian yo) or Ю (yu), which are instead written as two separate letters: Ја, Је, Ји, Јо, Ју. Ј can also be used as a semi-vowel, in place of й. The letter Щ is not used. When necessary, it is transliterated as either ШЧ or ШТ.

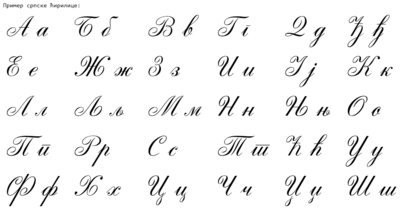

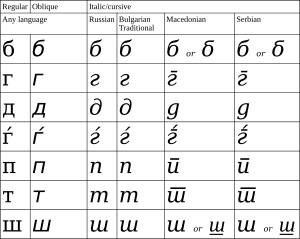

Serbian and Macedonian italic and cursive forms of lowercase letters б, г, д, п, and т, are allowed to differ from those used in other Cyrillic alphabets. The regular (upright) shapes are generally standardized among languages and there are no officially recognized variations.[17][18] That presents an obstacle in Unicode modeling, as the glyphs differ only in italic versions, and historically non-italic letters have been used in the same code positions. Serbian professional typography uses fonts specially crafted for the language to overcome the problem, but texts printed from common computers contain East Slavic rather than Serbian italic glyphs. Cyrillic fonts from Adobe,[19] Microsoft (Windows Vista and later) and a few other font houses include the Serbian variations (both regular and italic).

If the underlying font and Web technology provides support, the proper glyphs can be obtained by marking the text with appropriate language codes. Thus, in non-italic mode:

<span lang="sr">бгдпт</span>, produces бгдпт, same (except for the shape of б) as<span lang="ru">бгдпт</span>, producing бгдпт

whereas:

<span lang="sr" style="font-style: italic">бгдпт</span>gives бгдпт, and<span lang="ru" style="font-style: italic">бгдпт</span>produces бгдпт.

Since Unicode unifies different glyphs in same characters,[20] font support must be present to display the correct variant. Programs like Mozilla Firefox, LibreOffice (currently under Linux only), and some others provide required OpenType support. Of course, font families like GNU FreeFont, DejaVu, Ubuntu, Microsoft "C*" fonts from Windows Vista and above must be used.

See also

References

- Ronelle Alexander (15 August 2006). Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian, a Grammar: With Sociolinguistic Commentary. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-299-21193-6.

- Tomasz Kamusella (15 January 2009). The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-55070-4.

In addition, today, neither Bosniaks nor Croats, but only Serbs use Cyrillic in Bosnia.

- Entangled Histories of the Balkans: Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies. BRILL. 13 June 2013. pp. 414–. ISBN 978-90-04-25076-5.

- "Ćeranje ćirilice iz Crne Gore". www.novosti.rs.

- "Ivan Klajn: Ćirilica će postati arhaično pismo". B92.net.

- Cubberley, Paul (1996) "The Slavic Alphabets". in Daniels, Peter T., and William Bright, eds. (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507993-0.

- The life and times of Vuk Stefanović Karadžić, p. 387

- Vek i po od smrti Vuka Karadžića (in Serbian), Radio-Television of Serbia, 7 February 2014

- Andrej Mitrović, Serbia's great war, 1914-1918 p.78-79. Purdue University Press, 2007. ISBN 1-55753-477-2, ISBN 978-1-55753-477-4

- Ana S. Trbovich (2008). A Legal Geography of Yugoslavia's Disintegration. Oxford University Press. p. 102.

- Sabrina P. Ramet (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-building and Legitimation, 1918-2005. Indiana University Press. pp. 312–. ISBN 0-253-34656-8.

- Enver Redžić (2005). Bosnia and Herzegovina in the Second World War. Psychology Press. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-0-7146-5625-0.

- Alex J. Bellamy (2003). The Formation of Croatian National Identity: A Centuries-old Dream. Manchester University Press. pp. 138–. ISBN 978-0-7190-6502-6.

- David M. Crowe (13 September 2013). Crimes of State Past and Present: Government-Sponsored Atrocities and International Legal Responses. Routledge. pp. 61–. ISBN 978-1-317-98682-9.

- Yugoslav Survey. 43. Jugoslavija Publishing House. 2002. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- Article 10 of the Constitution of the Republic of Serbia (English version)

- Peshikan, Mitar; Jerković, Jovan; Pižurica, Mato (1994). Pravopis srpskoga jezika. Beograd: Matica Srpska. p. 42. ISBN 86-363-0296-X.

- Pravopis na makedonskiot jazik (PDF). Skopje: Institut za makedonski jazik Krste Misirkov. 2017. p. 3. ISBN 978-608-220-042-2.

- "Adobe Standard Cyrillic Font Specification - Technical Note #5013" (PDF). 18 February 1998. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-02-06. Retrieved 2010-08-19.

- "Unicode 8.0.0 ch.02 p.14-15" (PDF).

Sources

- Sir Duncan Wilson, The life and times of Vuk Stefanović Karadžić, 1787-1864: literacy, literature and national independence in Serbia, p. 387. Clarendon Press, 1970. Google Books

- Alphabet