Henry James

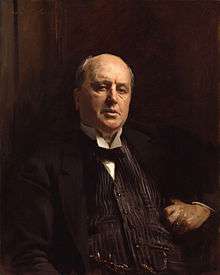

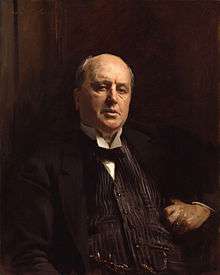

Henry James OM (15 April 1843 – 28 February 1916) was an American author, who became a British subject in the last year of his life, regarded as a key transitional figure between literary realism and literary modernism and is considered by many to be among the greatest novelists in the English language. He was the son of Henry James Sr. and the brother of renowned philosopher and psychologist William James and diarist Alice James.

Henry James OM | |

|---|---|

James in 1913 | |

| Born | 15 April 1843 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | 28 February 1916 (aged 72) Chelsea, London, England |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Citizenship | American, British |

| Alma mater | Harvard Law School |

| Period | 1863–1916 |

| Notable works | The American The Turn of the Screw The Portrait of a Lady What Maisie Knew The Wings of the Dove Daisy Miller The Ambassadors The Bostonians Washington Square |

| Relatives | Henry James Sr. (father) William James (brother) Alice James (sister) |

| Signature | .png) |

He is best known for a number of novels dealing with the social and marital interplay between émigré Americans, English people, and continental Europeans. Examples of such novels include The Portrait of a Lady, The Ambassadors, and The Wings of the Dove. His later works were increasingly experimental. In describing the internal states of mind and social dynamics of his characters, James often made use of a style in which ambiguous or contradictory motives and impressions were overlaid or juxtaposed in the discussion of a character's psyche. For their unique ambiguity, as well as for other aspects of their composition, his late works have been compared to impressionist painting.

His novella The Turn of the Screw has garnered a reputation as the most analysed and ambiguous ghost story in the English language and remains his most widely adapted work in other media. He also wrote a number of other highly regarded ghost stories and is considered one of the greatest masters of the field.

James published articles and books of criticism, travel, biography, autobiography, and plays. Born in the United States, James largely relocated to Europe as a young man and eventually settled in England, becoming a British citizen in 1915, one year before his death. James was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1911, 1912 and 1916.[1]

Life

Early years, 1843–1883

James was born at 21 Washington Place in New York City on 15 April 1843. His parents were Mary Walsh and Henry James Sr. His father was intelligent and steadfastly congenial. He was a lecturer and philosopher who had inherited independent means from his father, an Albany banker and investor. Mary came from a wealthy family long settled in New York City. Her sister Katherine lived with her adult family for an extended period of time. Henry Jr. was one of four boys, the others being William, who was one year his senior, and younger brothers Wilkinson (Wilkie) and Robertson. His younger sister was Alice. Both of his parents were of Irish and Scottish descent.[2]

The family first lived in Albany, at 70 N. Pearl St., and then moved to Fourteenth Street in New York City when James was still a young boy.[3] His education was calculated by his father to expose him to many influences, primarily scientific and philosophical; it was described by Percy Lubbock, the editor of his selected letters, as "extraordinarily haphazard and promiscuous."[4] James did not share the usual education in Latin and Greek classics. Between 1855 and 1860, the James' household traveled to London, Paris, Geneva, Boulogne-sur-Mer and Newport, Rhode Island, according to the father's current interests and publishing ventures, retreating to the United States when funds were low. Henry studied primarily with tutors and briefly attended schools while the family traveled in Europe. Their longest stays were in France, where Henry began to feel at home and became fluent in French. He had a stutter, which seems to have manifested itself only when he spoke English; in French, he did not stutter.[5]

In 1860 the family returned to Newport. There Henry became a friend of the painter John La Farge, who introduced him to French literature, and in particular, to Balzac. James later called Balzac his "greatest master," and said that he had learned more about the craft of fiction from him than from anyone else.[6]

In the autumn of 1861 Henry received an injury, probably to his back, while fighting a fire. This injury, which resurfaced at times throughout his life, made him unfit for military service in the American Civil War.[6]

In 1864 the James family moved to Boston, Massachusetts, to be near William, who had enrolled first in the Lawrence Scientific School at Harvard and then in the medical school. In 1862 Henry attended Harvard Law School, but realised that he was not interested in studying law. He pursued his interest in literature and associated with authors and critics William Dean Howells and Charles Eliot Norton in Boston and Cambridge, formed lifelong friendships with Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., the future Supreme Court Justice, and with James and Annie Fields, his first professional mentors.

His first published work was a review of a stage performance, "Miss Maggie Mitchell in Fanchon the Cricket," published in 1863.[7] About a year later, A Tragedy of Error, his first short story, was published anonymously. James's first payment was for an appreciation of Sir Walter Scott's novels, written for the North American Review. He wrote fiction and non-fiction pieces for The Nation and Atlantic Monthly, where Fields was editor. In 1871 he published his first novel, Watch and Ward, in serial form in the Atlantic Monthly. The novel was later published in book form in 1878.

During a 14-month trip through Europe in 1869–70, he met Ruskin, Dickens, Matthew Arnold, William Morris, and George Eliot. Rome impressed him profoundly. "Here I am then in the Eternal City," he wrote to his brother William. "At last—for the first time—I live!"[8] He attempted to support himself as a freelance writer in Rome, then secured a position as Paris correspondent for the New York Tribune, through the influence of its editor John Hay. When these efforts failed, he returned to New York City. During 1874 and 1875 he published Transatlantic Sketches, A Passionate Pilgrim, and Roderick Hudson. During this early period in his career he was influenced by Nathaniel Hawthorne.[9]

In 1869 he settled in London. There he established relationships with Macmillan and other publishers, who paid for serial installments that they would later publish in book form. The audience for these serialized novels was largely made up of middle-class women, and James struggled to fashion serious literary work within the strictures imposed by editors' and publishers' notions of what was suitable for young women to read. He lived in rented rooms but was able to join gentlemen's clubs that had libraries and where he could entertain male friends. He was introduced to English society by Henry Adams and Charles Milnes Gaskell, the latter introducing him to the Travellers' and the Reform Clubs.[10][11]

In the fall of 1875, he moved to the Latin Quarter of Paris. Aside from two trips to America, he spent the next three decades—the rest of his life—in Europe. In Paris he met Zola, Alphonse Daudet, Maupassant, Turgenev, and others.[12] He stayed in Paris only a year before moving to London.

In England he met the leading figures of politics and culture. He continued to be a prolific writer, producing The American (1877), The Europeans (1878), a revision of Watch and Ward (1878), French Poets and Novelists (1878), Hawthorne (1879), and several shorter works of fiction. In 1878 Daisy Miller established his fame on both sides of the Atlantic. It drew notice perhaps mostly because it depicted a woman whose behavior is outside the social norms of Europe. He also began his first masterpiece,[13] The Portrait of a Lady, which would appear in 1881.

In 1877 he first visited Wenlock Abbey in Shropshire, home of his friend Charles Milnes Gaskell whom he had met through Henry Adams. He was much inspired by the darkly romantic Abbey and the surrounding countryside, which features in his essay Abbeys and Castles.[10] In particular, the gloomy monastic fishponds behind the Abbey are said to have inspired the lake in The Turn of the Screw.[14]

While living in London, James continued to follow the careers of the "French realists," Émile Zola in particular. Their stylistic methods influenced his own work in the years to come.[15] Hawthorne's influence on him faded during this period, replaced by George Eliot and Ivan Turgenev.[9] The period from 1878 to 1881 saw the publication of The Europeans, Washington Square, Confidence, and The Portrait of a Lady. He visited America in 1882–1883, then returned to London.

The period from 1881 to 1883 was marked by several losses. His mother died in 1881, followed by his father a few months later, and then by his brother Wilkie. Emerson, an old family friend, died in 1882. His friend Turgenev died in 1883.

Middle years, 1884–1897

In 1884 James made another visit to Paris. There he met again with Zola, Daudet, and Goncourt. He had been following the careers of the French "realist" or "naturalist" writers, and was increasingly influenced by them.[15] In 1886, he published The Bostonians and The Princess Casamassima, both influenced by the French writers he'd studied assiduously. Critical reaction and sales were poor. He wrote to Howells that the books had hurt his career rather than helped because they had "reduced the desire, and demand, for my productions to zero".[16] During this time he became friends with Robert Louis Stevenson, John Singer Sargent, Edmund Gosse, George du Maurier, Paul Bourget, and Constance Fenimore Woolson. His third novel from the 1880s was The Tragic Muse. Although he was following the precepts of Zola in his novels of the '80s, their tone and attitude are closer to the fiction of Alphonse Daudet.[17] The lack of critical and financial success for his novels during this period led him to try writing for the theatre[18] (His dramatic works and his experiences with theatre are discussed below.).

In the last quarter of 1889, "for pure and copious lucre",[19] he started translating Port Tarascon, the third volume of Alphonse Daudet's adventures of Tartarin de Tarascon. Serialized in Harper's Monthly Magazine from June 1890, this translation praised as "clever" by The Spectator[20] was published in January 1891 by Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington.

After the stage failure of Guy Domville in 1895, James was near despair and thoughts of death plagued him.[21] The years spent on dramatic works were not entirely a loss. As he moved into the last phase of his career, he found ways to adapt dramatic techniques into the novel form.

In the late 1880s and throughout the 1890s, James made several trips through Europe. He spent a long stay in Italy in 1887. In that year the short novel The Aspern Papers and The Reverberator were published.

Late years, 1898–1916

In 1897–1898 he moved to Rye, Sussex and wrote The Turn of the Screw. 1899–1900 saw the publication of The Awkward Age and The Sacred Fount. During 1902–1904 he wrote The Ambassadors, The Wings of the Dove, and The Golden Bowl.

In 1904 he revisited America and lectured on Balzac. In 1906–1910 he published The American Scene and edited the "New York Edition", a 24-volume collection of his works. In 1910 his brother William died; Henry had just joined William from an unsuccessful search for relief in Europe on what then turned out to be his (Henry's) last visit to the United States (from summer 1910 to July 1911) and was near him according to a letter he wrote when he died.[22]

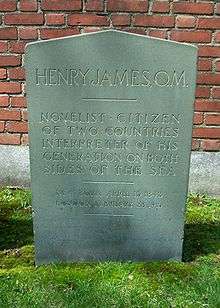

In 1913 he wrote his autobiographies, A Small Boy and Others, and Notes of a Son and Brother. After the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, he did war work. In 1915 he became a British subject and was awarded the Order of Merit the following year. He died on 28 February 1916, in Chelsea, London, and was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium. As he requested, his ashes were buried in Cambridge Cemetery in Massachusetts.[23]

Sexuality

James regularly rejected suggestions that he should marry, and after settling in London, proclaimed himself "a bachelor". F. W. Dupee, in several volumes on the James family, originated the theory that he had been in love with his cousin, Mary ("Minnie") Temple, but that a neurotic fear of sex kept him from admitting such affections: "James's invalidism ... was itself the symptom of some fear of or scruple against sexual love on his part." Dupee used an episode from James's memoir, A Small Boy and Others, recounting a dream of a Napoleonic image in the Louvre, to exemplify James's romanticism about Europe, a Napoleonic fantasy into which he fled.[24][25]

Dupee had not had access to the James family papers and worked principally from James's published memoir of his older brother, William, and the limited collection of letters edited by Percy Lubbock, heavily weighted toward James's last years. His account therefore moved directly from James's childhood, when he trailed after his older brother, to elderly invalidism. As more material became available to scholars, including the diaries of contemporaries and hundreds of affectionate and sometimes erotic letters written by James to younger men, the picture of neurotic celibacy gave way to a portrait of a closeted homosexual.

Between 1953 and 1972, Leon Edel wrote a major five-volume biography of James, which accessed unpublished letters and documents after Edel gained the permission of James's family. Edel's portrayal of James included the suggestion he was celibate. It was a view first propounded by critic Saul Rosenzweig in 1943.[26] In 1996 Sheldon M. Novick published Henry James: The Young Master, followed by Henry James: The Mature Master (2007). The first book "caused something of an uproar in Jamesian circles"[27] as it challenged the previous received notion of celibacy, a once-familiar paradigm in biographies of homosexuals when direct evidence was non-existent. Novick also criticized Edel for following the discounted Freudian interpretation of homosexuality "as a kind of failure."[27] The difference of opinion erupted in a series of exchanges between Edel and Novick which were published by the online magazine Slate, with the latter arguing that even the suggestion of celibacy went against James's own injunction "live!"—not "fantasize!"[28]

A letter James wrote in old age to Hugh Walpole has been cited as an explicit statement of this. Walpole confessed to him of indulging in "high jinks", and James wrote a reply endorsing it: "We must know, as much as possible, in our beautiful art, yours & mine, what we are talking about — & the only way to know it is to have lived & loved & cursed & floundered & enjoyed & suffered — I don’t think I regret a single ‘excess’ of my responsive youth".[29]

The interpretation of James as living a less austere emotional life has been subsequently explored by other scholars.[30] The often intense politics of Jamesian scholarship has also been the subject of studies.[31] Author Colm Tóibín has said that Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick's Epistemology of the Closet made a landmark difference to Jamesian scholarship by arguing that he be read as a homosexual writer whose desire to keep his sexuality a secret shaped his layered style and dramatic artistry. According to Tóibín such a reading "removed James from the realm of dead white males who wrote about posh people. He became our contemporary."[32]

James's letters to expatriate American sculptor Hendrik Christian Andersen have attracted particular attention. James met the 27-year-old Andersen in Rome in 1899, when James was 56, and wrote letters to Andersen that are intensely emotional: "I hold you, dearest boy, in my innermost love, & count on your feeling me—in every throb of your soul". In a letter of 6 May 1904, to his brother William, James referred to himself as "always your hopelessly celibate even though sexagenarian Henry".[33] How accurate that description might have been is the subject of contention among James's biographers,[34][nb 1] but the letters to Andersen were occasionally quasi-erotic: "I put, my dear boy, my arm around you, & feel the pulsation, thereby, as it were, of our excellent future & your admirable endowment."[35]

His numerous letters to the many young homosexual men among his close male friends are more forthcoming. To his homosexual friend, Howard Sturgis, James could write: "I repeat, almost to indiscretion, that I could live with you. Meanwhile I can only try to live without you."[36] In another letter to Howard Sturgis, following a long visit, James refers jocularly to their "happy little congress of two".[37] In letters to Hugh Walpole he pursues convoluted jokes and puns about their relationship, referring to himself as an elephant who "paws you oh so benevolently" and winds about Walpole his "well meaning old trunk".[38] His letters to Walter Berry printed by the Black Sun Press have long been celebrated for their lightly veiled eroticism.[39]

However, James corresponded in equally extravagant language with his many female friends, writing, for example, to fellow novelist Lucy Clifford: "Dearest Lucy! What shall I say? when I love you so very, very much, and see you nine times for once that I see Others! Therefore I think that — if you want it made clear to the meanest intelligence — I love you more than I love Others."[40] To his New York friend Mary Cadwalader Jones: "Dearest Mary Cadwalader. I yearn over you, but I yearn in vain; & your long silence really breaks my heart, mystifies, depresses, almost alarms me, to the point even of making me wonder if poor unconscious & doting old Célimare [Jones's pet name for James] has 'done' anything, in some dark somnambulism of the spirit, which has ... given you a bad moment, or a wrong impression, or a 'colourable pretext' ... However these things may be, he loves you as tenderly as ever; nothing, to the end of time, will ever detach him from you, & he remembers those Eleventh St. matutinal intimes hours, those telephonic matinées, as the most romantic of his life ..."[41] His long friendship with American novelist, Constance Fenimore Woolson, in whose house he lived for a number of weeks in Italy in 1887, and his shock and grief over her suicide in 1894, are discussed in detail in Edel's biography and play a central role in a study by Lyndall Gordon. Edel conjectured that Woolson was in love with James and killed herself in part because of his coldness, but Woolson's biographers have objected to Edel's account.[nb 2]

Works

Style and themes

James is one of the major figures of trans-Atlantic literature. His works frequently juxtapose characters from the Old World (Europe), embodying a feudal civilisation that is beautiful, often corrupt, and alluring, and from the New World (United States), where people are often brash, open, and assertive and embody the virtues of the new American society — particularly personal freedom and a more highly evolved moral character. James explores this clash of personalities and cultures, in stories of personal relationships in which power is exercised well or badly.

His protagonists were often young American women facing oppression or abuse, and as his secretary Theodora Bosanquet remarked in her monograph Henry James at Work:

When he walked out of the refuge of his study and into the world and looked around him, he saw a place of torment, where creatures of prey perpetually thrust their claws into the quivering flesh of doomed, defenseless children of light ... His novels are a repeated exposure of this wickedness, a reiterated and passionate plea for the fullest freedom of development, unimperiled by reckless and barbarous stupidity.[42]

Philip Guedalla jokingly described three phases in the development of James's prose: "James I, James II, and The Old Pretender,"[43] and observers do often group his works of fiction into three periods. In his apprentice years, culminating with the masterwork The Portrait of a Lady, his style was simple and direct (by the standards of Victorian magazine writing) and he experimented widely with forms and methods, generally narrating from a conventionally omniscient point of view. Plots generally concern romance, except for the three big novels of social commentary that conclude this period. In the second period, as noted above, he abandoned the serialized novel and from 1890 to about 1897, he wrote short stories and plays. Finally, in his third and last period he returned to the long, serialised novel. Beginning in the second period, but most noticeably in the third, he increasingly abandoned direct statement in favour of frequent double negatives, and complex descriptive imagery. Single paragraphs began to run for page after page, in which an initial noun would be succeeded by pronouns surrounded by clouds of adjectives and prepositional clauses, far from their original referents, and verbs would be deferred and then preceded by a series of adverbs. The overall effect could be a vivid evocation of a scene as perceived by a sensitive observer. It has been debated whether this change of style was engendered by James's shifting from writing to dictating to a typist,[44] a change made during the composition of What Maisie Knew.[45]

In its intense focus on the consciousness of his major characters, James's later work foreshadows extensive developments in 20th century fiction.[46][nb 3] Indeed, he might have influenced stream-of-consciousness writers such as Virginia Woolf, who not only read some of his novels but also wrote essays about them.[47] Both contemporary and modern readers have found the late style difficult and unnecessary; his friend Edith Wharton, who admired him greatly, said that there were passages in his work that were all but incomprehensible.[48] James was harshly portrayed by H. G. Wells as a hippopotamus laboriously attempting to pick up a pea that had got into a corner of its cage.[49] The "late James" style was ably parodied by Max Beerbohm in "The Mote in the Middle Distance".[50]

More important for his work overall may have been his position as an expatriate, and in other ways an outsider, living in Europe. While he came from middle-class and provincial beginnings (seen from the perspective of European polite society) he worked very hard to gain access to all levels of society, and the settings of his fiction range from working class to aristocratic, and often describe the efforts of middle-class Americans to make their way in European capitals. He confessed he got some of his best story ideas from gossip at the dinner table or at country house weekends.[nb 4] He worked for a living, however, and lacked the experiences of select schools, university, and army service, the common bonds of masculine society. He was furthermore a man whose tastes and interests were, according to the prevailing standards of Victorian era Anglo-American culture, rather feminine, and who was shadowed by the cloud of prejudice that then and later accompanied suspicions of his homosexuality.[51][nb 5] Edmund Wilson famously compared James's objectivity to Shakespeare's:

One would be in a position to appreciate James better if one compared him with the dramatists of the seventeenth century—Racine and Molière, whom he resembles in form as well as in point of view, and even Shakespeare, when allowances are made for the most extreme differences in subject and form. These poets are not, like Dickens and Hardy, writers of melodrama—either humorous or pessimistic, nor secretaries of society like Balzac, nor prophets like Tolstoy: they are occupied simply with the presentation of conflicts of moral character, which they do not concern themselves about softening or averting. They do not indict society for these situations: they regard them as universal and inevitable. They do not even blame God for allowing them: they accept them as the conditions of life.[52]

It is also possible to see many of James's stories as psychological thought-experiments about selection. In his preface to the New York edition of The American he describes the development of the story in his mind as exactly such: the "situation" of an American, "some robust but insidiously beguiled and betrayed, some cruelly wronged, compatriot..." with the focus of the story being on the response of this wronged man.[53] The Portrait of a Lady may be an experiment to see what happens when an idealistic young woman suddenly becomes very rich. In many of his tales, characters seem to exemplify alternative futures and possibilities, as most markedly in "The Jolly Corner", in which the protagonist and a ghost-doppelganger live alternative American and European lives; and in others, like The Ambassadors, an older James seems fondly to regard his own younger self facing a crucial moment.[nb 6]

Major novels

The first period of James's fiction, usually considered to have culminated in The Portrait of a Lady, concentrated on the contrast between Europe and America. The style of these novels is generally straightforward and, though personally characteristic, well within the norms of 19th-century fiction. Roderick Hudson (1875) is a Künstlerroman that traces the development of the title character, an extremely talented sculptor. Although the book shows some signs of immaturity—this was James's first serious attempt at a full-length novel—it has attracted favourable comment due to the vivid realisation of the three major characters: Roderick Hudson, superbly gifted but unstable and unreliable; Rowland Mallet, Roderick's limited but much more mature friend and patron; and Christina Light, one of James's most enchanting and maddening femmes fatales. The pair of Hudson and Mallet has been seen as representing the two sides of James's own nature: the wildly imaginative artist and the brooding conscientious mentor.[54]

In The Portrait of a Lady (1881) James concluded the first phase of his career with a novel that remains his most popular piece of long fiction. The story is of a spirited young American woman, Isabel Archer, who "affronts her destiny" and finds it overwhelming. She inherits a large amount of money and subsequently becomes the victim of Machiavellian scheming by two American expatriates. The narrative is set mainly in Europe, especially in England and Italy. Generally regarded as the masterpiece of his early phase, The Portrait of a Lady is described as a psychological novel, exploring the minds of his characters, and almost a work of social science, exploring the differences between Europeans and Americans, the old and the new worlds.[55]

The second period of James's career, which extends from the publication of The Portrait of a Lady through the end of the nineteenth century, features less popular novels including The Princess Casamassima, published serially in The Atlantic Monthly in 1885–1886, and The Bostonians, published serially in The Century Magazine during the same period. This period also featured James's celebrated Gothic novella, The Turn of the Screw (1898).

The third period of James's career reached its most significant achievement in three novels published just around the start of the 20th century: The Wings of the Dove (1902), The Ambassadors (1903), and The Golden Bowl (1904). Critic F. O. Matthiessen called this "trilogy" James's major phase, and these novels have certainly received intense critical study. It was the second-written of the books, The Wings of the Dove (1902) that was the first published because it attracted no serialization.[56] This novel tells the story of Milly Theale, an American heiress stricken with a serious disease, and her impact on the people around her. Some of these people befriend Milly with honourable motives, while others are more self-interested. James stated in his autobiographical books that Milly was based on Minny Temple, his beloved cousin who died at an early age of tuberculosis. He said that he attempted in the novel to wrap her memory in the "beauty and dignity of art".[57]

Shorter narratives

James was particularly interested in what he called the "beautiful and blest nouvelle", or the longer form of short narrative. Still, he produced a number of very short stories in which he achieved notable compression of sometimes complex subjects. The following narratives are representative of James's achievement in the shorter forms of fiction.[nb 7]

- "A Tragedy of Error" (1864), short story

- "The Story of a Year" (1865), short story

- A Passionate Pilgrim (1871), novella

- Madame de Mauves (1874), novella

- Daisy Miller (1878), novella

- The Aspern Papers (1888), novella

- The Lesson of the Master (1888), novella

- The Pupil (1891), short story

- "The Figure in the Carpet" (1896), short story

- The Beast in the Jungle (1903), novella

- An International Episode (1878)

- Picture and Text

- Four Meetings (1885)

- A London Life, and Other Tales (1889)

- The Spoils of Poynton (1896)

- Embarrassments (1896)

- The Two Magics: The Turn of the Screw, Covering End (1898)

- A Little Tour of France (1900)

- The Sacred Fount (1901)

- Views and Reviews (1908)

- The Wings of the Dove, Volume I (1902)

- The Wings of the Dove, Volume II (1909)

- The Finer Grain (1910)

- The Outcry (1911)

- Lady Barbarina: The Siege of London, An International Episode and Other Tales (1922)

- The Birthplace (1922)

Plays

At several points in his career James wrote plays, beginning with one-act plays written for periodicals in 1869 and 1871[58] and a dramatisation of his popular novella Daisy Miller in 1882.[59] From 1890 to 1892, having received a bequest that freed him from magazine publication, he made a strenuous effort to succeed on the London stage, writing a half-dozen plays of which only one, a dramatisation of his novel The American, was produced. This play was performed for several years by a touring repertory company and had a respectable run in London, but did not earn very much money for James. His other plays written at this time were not produced.

In 1893, however, he responded to a request from actor-manager George Alexander for a serious play for the opening of his renovated St. James's Theatre, and wrote a long drama, Guy Domville, which Alexander produced. There was a noisy uproar on the opening night, 5 January 1895, with hissing from the gallery when James took his bow after the final curtain, and the author was upset. The play received moderately good reviews and had a modest run of four weeks before being taken off to make way for Oscar Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest, which Alexander thought would have better prospects for the coming season.

After the stresses and disappointment of these efforts James insisted that he would write no more for the theatre, but within weeks had agreed to write a curtain-raiser for Ellen Terry. This became the one-act "Summersoft", which he later rewrote into a short story, "Covering End", and then expanded into a full-length play, The High Bid, which had a brief run in London in 1907, when James made another concerted effort to write for the stage. He wrote three new plays, two of which were in production when the death of Edward VII on 6 May 1910 plunged London into mourning and theatres closed. Discouraged by failing health and the stresses of theatrical work, James did not renew his efforts in the theatre, but recycled his plays as successful novels. The Outcry was a best-seller in the United States when it was published in 1911. During the years 1890–1893 when he was most engaged with the theatre, James wrote a good deal of theatrical criticism and assisted Elizabeth Robins and others in translating and producing Henrik Ibsen for the first time in London.[60]

Leon Edel argued in his psychoanalytic biography that James was traumatised by the opening night uproar that greeted Guy Domville, and that it plunged him into a prolonged depression. The successful later novels, in Edel's view, were the result of a kind of self-analysis, expressed in fiction, which partly freed him from his fears. Other biographers and scholars have not accepted this account, however; the more common view being that of F.O. Matthiessen, who wrote: "Instead of being crushed by the collapse of his hopes [for the theatre]... he felt a resurgence of new energy."[61][62][63]

Non-fiction

Beyond his fiction, James was one of the more important literary critics in the history of the novel. In his classic essay The Art of Fiction (1884), he argued against rigid prescriptions on the novelist's choice of subject and method of treatment. He maintained that the widest possible freedom in content and approach would help ensure narrative fiction's continued vitality. James wrote many valuable critical articles on other novelists; typical is his book-length study of Nathaniel Hawthorne, which has been the subject of critical debate. Richard Brodhead has suggested that the study was emblematic of James's struggle with Hawthorne's influence, and constituted an effort to place the elder writer "at a disadvantage."[64] Gordon Fraser, meanwhile, has suggested that the study was part of a more commercial effort by James to introduce himself to British readers as Hawthorne's natural successor.[65]

When James assembled the New York Edition of his fiction in his final years, he wrote a series of prefaces that subjected his own work to searching, occasionally harsh criticism.[nb 8]

At 22 James wrote The Noble School of Fiction for The Nation's first issue in 1865. He would write, in all, over 200 essays and book, art, and theatre reviews for the magazine.[66]

For most of his life James harboured ambitions for success as a playwright. He converted his novel The American into a play that enjoyed modest returns in the early 1890s. In all he wrote about a dozen plays, most of which went unproduced. His costume drama Guy Domville failed disastrously on its opening night in 1895. James then largely abandoned his efforts to conquer the stage and returned to his fiction. In his Notebooks he maintained that his theatrical experiment benefited his novels and tales by helping him dramatise his characters' thoughts and emotions. James produced a small but valuable amount of theatrical criticism, including perceptive appreciations of Henrik Ibsen.[67][nb 9]

With his wide-ranging artistic interests, James occasionally wrote on the visual arts. Perhaps his most valuable contribution was his favourable assessment of fellow expatriate John Singer Sargent, a painter whose critical status has improved markedly in recent decades. James also wrote sometimes charming, sometimes brooding articles about various places he visited and lived in. His most famous books of travel writing include Italian Hours (an example of the charming approach) and The American Scene (on the brooding side).[nb 10]

James was one of the great letter-writers of any era. More than ten thousand of his personal letters are extant, and over three thousand have been published in a large number of collections. A complete edition of James's letters began publication in 2006, edited by Pierre Walker and Greg Zacharias. As of 2014, eight volumes have been published, covering the period from 1855 to 1880.[68] James's correspondents included celebrated contemporaries like Robert Louis Stevenson, Edith Wharton and Joseph Conrad, along with many others in his wide circle of friends and acquaintances. The letters range from the "mere twaddle of graciousness"[69][nb 11] to serious discussions of artistic, social and personal issues.

Very late in life James began a series of autobiographical works: A Small Boy and Others, Notes of a Son and Brother, and the unfinished The Middle Years. These books portray the development of a classic observer who was passionately interested in artistic creation but was somewhat reticent about participating fully in the life around him.[nb 12]

Reception

Criticism, biographies and fictional treatments

James's work has remained steadily popular with the limited audience of educated readers to whom he spoke during his lifetime, and has remained firmly in the canon, but, after his death, some American critics, such as Van Wyck Brooks, expressed hostility towards James for his long expatriation and eventual naturalisation as a British subject.[70] Other critics such as E. M. Forster complained about what they saw as James's squeamishness in the treatment of sex and other possibly controversial material, or dismissed his late style as difficult and obscure, relying heavily on extremely long sentences and excessively latinate language.[71] Similarly Oscar Wilde criticised him for writing "fiction as if it were a painful duty".[72] Vernon Parrington, composing a canon of American literature, condemned James for having cut himself off from America. Jorge Luis Borges wrote about him, "Despite the scruples and delicate complexities of James, his work suffers from a major defect: the absence of life."[73] And Virginia Woolf, writing to Lytton Strachey, asked, "Please tell me what you find in Henry James. ... we have his works here, and I read, and I can't find anything but faintly tinged rose water, urbane and sleek, but vulgar and pale as Walter Lamb. Is there really any sense in it?"[74] The novelist W. Somerset Maugham wrote, "He did not know the English as an Englishman instinctively knows them and so his English characters never to my mind quite ring true," and argued "The great novelists, even in seclusion, have lived life passionately. Henry James was content to observe it from a window." [75] Maugham nevertheless wrote, "The fact remains that those last novels of his, notwithstanding their unreality, make all other novels, except the very best, unreadable." [76] Colm Tóibín observed that James "never really wrote about the English very well. His English characters don't work for me."[77]

Despite these criticisms, James is now valued for his psychological and moral realism, his masterful creation of character, his low-key but playful humour, and his assured command of the language. In his 1983 book, The Novels of Henry James, Edward Wagenknecht offers an assessment that echoes Theodora Bosanquet's:

"To be completely great," Henry James wrote in an early review, "a work of art must lift up the heart," and his own novels do this to an outstanding degree ... More than sixty years after his death, the great novelist who sometimes professed to have no opinions stands foursquare in the great Christian humanistic and democratic tradition. The men and women who, at the height of World War II, raided the secondhand shops for his out-of-print books knew what they were about. For no writer ever raised a braver banner to which all who love freedom might adhere.[78]

William Dean Howells saw James as a representative of a new realist school of literary art which broke with the English romantic tradition epitomised by the works of Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray. Howells wrote that realism found "its chief exemplar in Mr. James... A novelist he is not, after the old fashion, or after any fashion but his own."[79] F.R. Leavis championed Henry James as a novelist of "established pre-eminence" in The Great Tradition (1948), asserting that The Portrait of a Lady and The Bostonians were "the two most brilliant novels in the language."[80] James is now prized as a master of point of view who moved literary fiction forward by insisting in showing, not telling, his stories to the reader.

Portrayals in fiction

Henry James has been the subject of a number of novels and stories, including the following:[81]

- Boon by H.G. Wells

- Author, Author by David Lodge

- Youth by J.M. Coetzee

- The Master by Colm Tóibín

- Hotel de Dream by Edmund White

- Lions at Lamb House by Edwin M. Yoder

- Felony by Emma Tennant

- Dictation by Cynthia Ozick

- The James Boys by Richard Liebmann-Smith

- The Open Door, by Elizabeth Maguire

- The Great Divide by Rex Hunter[82]

- The Master at St. Bartholomew's Hospital, 1914–1916, by Joyce Carol Oates

- The Typewriter's Tale, by Michael Heyns

- Henry James' Midnight Song, by Carol de Chellis Hill

- The Fifth Heart, by Dan Simmons

- Empire, by Gore Vidal

- The Maze at Windermere, by Gregory Blake Smith

- Ringrose The Pirate, by Don Nigro

David Lodge also wrote a long essay about writing about Henry James in his collection The Year of Henry James: The Story of a Novel.

Adaptations

Henry James stories and novels have been adapted to film, television and music video over 150 times (some TV shows did upwards of a dozen stories) from 1933–2018.[83] The majority of these are in English, but there are also adaptations in French (13), Spanish (7), Italian (6), German (5), Portuguese (1), Yugoslavian (1) and Swedish (1).[83] Those most frequently adapted include:

- The Turn of the Screw (28 times)

- The Aspern Papers (17 times)

- Washington Square (8 times), as The Heiress (6 times), as Victoria (once)

- The Wings of the Dove (9 times)

- The Bostonians (4 times)

- Daisy Miller (4 times)

- The Sense of the Past (4 times)

- The Ambassadors (3 times)

- The Portrait of a Lady (3 times)

- The American (3 times)

- What Maisie Knew (3 times)

- The Golden Bowl (2 times)

Notes

- See volume four of Edel's referenced biography, pp. 306–316, for a particularly long and inconclusive discussion on the subject. See also Bradley (1999) and (2000).

- See e.g. Cheryl Torsney, Constance Fenimore Woolson: The Grief of Artistry (1989, "Edel's text ... a convention-laden male fantasy").

- See James's prefaces, Horne's study of his revisions for The New York Edition, Edward Wagenknecht's The Novels of Henry James (1983) among many discussions of the changes in James's narrative technique and style over the course of his career.

- James's prefaces to the New York Edition of his fiction often discuss such origins for his stories. See, for instance, the preface to The Spoils of Poynton.

- James himself noted his "outsider" status. In a letter of 2 October 1901, to W. Morton Fullerton, James talked of the "essential loneliness of my life" as "the deepest thing" about him.[51]

- Millicent Bell explores such themes in her monograph Meaning in Henry James

- For further critical analysis of these narratives, see the referenced editions of James's tales and The Turn of the Screw. The referenced books of criticism also discuss many of James's short narratives.

- See the referenced editions of James's criticism and the related articles in the "Literary criticism" part of the "Notable works by James" section for further discussion of his critical essays.

- For a general discussion of James's efforts as a playwright, see Edel's referenced edition of his plays.

- Further information about these works can be found in the related articles in the "Travel writings" and "Visual arts criticism" parts of the "Notable works by James" section and in the referenced editions of James's travel writings.

- Further information on James's letters can be found at The Online Calendar of Henry James's Letters. For more information on the complete edition of James's letters, see The Henry James Scholar's Guide to Web Sites.

- See the referenced edition of James's autobiographical books by F.W. Dupee, which includes a critical introduction, an extensive index, and notes.

^James was also an eager poet – his peak after his famous failure Guy Domville in which supposedly many poems were written (F. W. Dupee), most revolving around negative connotations (possibly due to his state of depression following abject failure of his premièr play on its opening night of 1895) like death, darkness etc. Most of these have been lost, but his more popular works such as 'In the darkness' and 'death bejewel'd' have remained.

Citations

- "Nomination Database". www.nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017.

- Kaplan, Fred. Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, A Biography. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992. Print.

- Grondahl, Paul (5 December 2013). "James Family Plot (1771–1832): Patriarch William James and relatives of novelist Henry James". Times Union.

- Letters of William James, p. 3, https://books.google.com/books?id=3VQ-AQAAIAAJ

- "The Man Who Talked Like a Book, Wrote Like He Spoke" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 December 2017.

- Powers (1970), p. 11

- Novick (1996), p. 431

- Powers (1970), p. 12

- Powers (1970), p. 16

- Gamble, Cynthia 2008, John Ruskin, Henry James and the Shropshire Lads, London: New European Publications

- Gamble, Cynthia, 2015 – (in production) Wenlock Abbey 1857–1919: A Shropshire Country House and the Milnes Gaskell Family, Ellingham Press.

- Powers (1970), p. 14

- Powers (1970), p. 15

- Gamble, Cynthia, 2015 Wenlock Abbey 1857–1919: A Shropshire Country House and the Milnes Gaskell Family, Ellingham Press.

- Powers (1970), p. 17

- Edel 1955, p. 55.

- Powers (1970), p. 19

- Powers (1970), p. 20

- Letter to Grace Norton, 22 Septembre 1890. Quoted in E. Harden, A Henry James Chronology, p. 85.

- Port Tarascon, Literary supplement to The Spectator, n°3266, 31 January 1891, p. 147.

- Powers (1970), p. 28

- Kaplan chapter 15.

- Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Locations 23458-23459). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition.

- Dupee (1949)

- Dupee (1951)

- Graham, Wendy "Henry James's Twarted Love", Stanford University Press, 1999, p10

- Leavitt, David (23 December 2007). "A Beast in the Jungle". New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 May 2017.

- "Henry James's Love Life". Slate. 19 December 1996. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017.

- Leavitt, David, 'A Beast in the Jungle', The New York Times, 23 December 2007

- Graham, Wendy "Henry James's Thwarted Love"; Bradley, John "Henry James and Homo-Erotic Desire"; Haralson, Eric "Henry James and Queer Modernity".

- Anesko, Michael "Monopolizing the Master: Henry James and the Politics of Modern Literary Scholarship", Stanford University Press

- Tóibín, Colm (20 February 2016). "How Henry James's family tried to keep him in the closet". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 May 2017.

- Ignas Skrupskelis and Elizabeth Bradley (1994) p. 271.

- Edel, 306–316

- Zorzi (2004)

- Gunter & Jobe (2001)

- Gunter & Jobe (2001), p. 125

- Gunter & Jobe (2001), p. 179

- Black Sun Press (1927)

- Demoor and Chisholm (1999) p.79

- Gunter (2000), p. 146

- Bosanquet (1982) pp. 275–276

- Guedalla, Philip (1921). Supers & Supermen: Studies in Politics, History and Letters Archived 25 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, p. 45. Alfred A. Knopf. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- Miller, James E. Jr., ed. (1972). Theory of Fiction: Henry James Archived 2 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 268–69. University of Nebraska Press. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- Edel, Leon, ed. (1984). Henry James: Letters, Vol. IV, 1895–1916 Archived 2 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, p. 4. Harvard University Press. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- Wagenknecht (1983).

- Woolf (March 2003) pp. 33, 39–40, 58, 86, 215, 301, 351.

- Edith Wharton (1925) pp. 90–91

- H. G. Wells, Boon (1915) p. 101.

- Beerbohm, Max (1922). "The Mote in the Middle Distance." In A Christmas Garland Archived 25 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, p. 1. E.P. Dutton & Company. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- Leon Edel (1984) volume 4, p. 170

- Dabney (1983) pp. 128–129

- The American, 1907, p. vi–vii

- Kraft (1969) p. 68.

- Brownstein (2004)

- Hazel Hutchison, Brief Lives: Henry James. London: Hesperus Press, 2012: "The elegiac tone of the novel did not appeal to periodical editors, and the novel went straight into book form in 1902, ahead of The Ambassadors, which ran in the North American Review from January to December 1903 and was published as a book later that same year." Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- Posnock (1987) p. 114

- Edel (1990) pp. 75, 89

- Edel (1990) p.121

- Novick (2007) pp.15–160 et passim.

- Matthiessen and Murdoch (1981) p. 179.

- Bradley (1999) p. 21, n

- Novick (2007) pp. 219–225 et passim.

- Richard Brodhead. The School of Hawthorne (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), 137.

- Gordon Fraser. "Anxiety of Audience: Economies of Readership in James's Hawthorne." The Henry James Review 34, no. 1 (2013): 1–2.

- vanden Heuvel (1990) p. 5

- Wade (1948) pp. 243–260.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Edel (1983) volume 4 p. 208

- Brooks (1925)

- Forster (1956) pp. 153–163

- Oscar Wilde Quotes – Page 6. BrainyQuote. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- Borges and de Torres (1971) p. 55.

- Reading Experience Database Display Record Archived 13 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Can-red-lec.library.dal.ca. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- W. Somerset Maugham, The Vagrant Mood, p203.

- Maugham, op. cit., p209.

- Colm Tóibín in conversation with Chris Lydon, in Cambridge, 2004 Archived 19 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- Wagenknecht (1983) pp. 261–262

- Lauter (2010) p. 364.

- F.R. Leavis, The Great Tradition (New York University Press, 1969), p. 155.

- "Henry James as a fictional character". blog.loa.org. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014.

- Australia, Writing. "Writing Australia Unpublished Manuscript Award 2013 – Shortlist Announcement". Archived from the original on 5 March 2014.

- "Henry James". IMDb.

References

- Harold Bloom (2009) [2001]. Henry James. Infobase Publishing, originally published by Chelsea House. ISBN 978-1-4381-1601-3.

- Jorge Luis Borges and Esther Zemborain de Torres (1971). An Introduction to American Literature. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

- Theodora Bosanquet (1982). Henry James At Work. Haskell House Publishers Inc. pp. 275–276. ISBN 0-8383-0009-X

- John R. Bradley, ed. (1999). Henry James and Homo-Erotic Desire. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-21764-1

- John R. Bradley (2000). I Henry James on Stage and Screen Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-79214-9

- John R. Bradley (2000). Henry James's Permanent Adolescence. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-91874-6

- Van Wyck Brooks (1925). The Pilgrimage of Henry James

- Gabriel Brownstein (2004). "Introduction," in James, Henry. Portrait of a Lady, Barnes & Noble Classics series, Spark Educational Publishing.

- Lewis Dabney, ed. (1983). The Portable Edmund Wilson. ISBN 0-14-015098-6

- Marysa Demoor and Monty Chisholm, editors (1999). Bravest of Women and Finest of Friends: Henry James's Letters to Lucy Clifford, University of Victoria (1999), p. 79 ISBN 0-920604-67-6

- F.W. Dupee (1951). Henry James William Sloane Associates, The American Men of Letters Series.

- Leon Edel, ed. (1955). The Selected Letters of Henry James New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, Vol. 1

- Leon Edel, ed. (1983). Henry James Letters.

- Leon Edel, ed. (1990). The Complete Plays of Henry James. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504379-0

- E.M. Forster (1956). Aspects of the Novel ISBN 0-674-38780-5

- Gunter, Susan (2000). Dear Munificent Friends: Henry James's Letters to Four Women. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-11010-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gunter, Susan E.; Jobe, Steven H. (2001). Dearly Beloved Friends: Henry James's Letters to Younger Men. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-11009-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Katrina vanden Heuvel (1990). The Nation 1865–1990, Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 1-56025-001-1

- James Kraft (1969). The early tales of Henry James. Southern Illinois University Press.

- Paul Lauter (2010). A companion to American literature and culture. Chichester; Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 364. ISBN 0-631-20892-5

- Percy Lubbock, ed. (1920). The Letters of Henry James, vol. 1. New York: Scribner.

- F. O. Matthiessen and Kenneth Murdock, editors (1981) The Notebooks of Henry James. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-51104-9

- Novick, Sheldon M (1996). Henry James: The Young Master. Random House. ISBN 0-394-58655-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sheldon M. Novick (2007). Henry James: The Mature Master. Random House; 2007. ISBN 978-0-679-45023-8.

- Ross Posnock (1987). "James, Browning, and the Theatrical Self," in Neuman, Mark and Payne, Michael. Self, sign, and symbol. Bucknell University Press.

- Powers, Lyall H (1970). Henry James: An Introduction and Interpretation. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ignas Skrupskelis and Elizabeth Bradley, editors. (1994). The Correspondence of William James: Volume 3, William and Henry. 1897–1910. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

- Allan Wade, ed. (1948). Henry James: The Scenic Art, Notes on Acting and the Drama 1872–1901.

- Edward Wagenknecht (1983). The Novels of Henry James.

- Edith Wharton (1925) The Writing of Fiction.

- Virginia Woolf (2003). A Writer's Diary: Being Extracts from the Diary of Virginia Woolf. Harcourt. p. 33, 39–40, 58, 86, 215, 301, 351. ISBN 978-0-15-602791-5.

- H.G. Wells, Boon. (1915) The Mind of the Race, The Wild Asses of the Devil, and The Last Trump. London: T. Fisher Unwin p. 101.

- Rosella Mamoli Zorzi, ed. (2004). Beloved Boy: Letters to Hendrik C. Andersen, 1899–1915. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0-8139-2270-4

Further reading

General

- A Bibliography of Henry James: Third Edition by Leon Edel, Dan Laurence and James Rambeau (1982). ISBN 1-58456-005-3

- A Henry James Encyclopedia by Robert L. Gale (1989). ISBN 0-313-25846-5

- A Henry James Chronology by Edgar F. Harden (2005). ISBN 1403942293

- The Daily Henry James: A Year of Quotes from the Work of the Master. Edited by Michael Gorra (2016). ISBN 978-0-226-40854-5

Autobiography

- A Small Boy and Others: A Critical Edition edited by Peter Collister (2011). ISBN 0813930820

- Notes of a Son and Brother and The Middle Years: A Critical Edition edited by Peter Collister (2011) ISBN 0813930847

- Autobiographies edited by Philip Horne (2016). Contains A Small Boy and Others, Notes of a Son and Brother, The Middle Years, other autobiographical writings, and Henry James at Work, by Theodora Bosanquet. ISBN 9781598534719

Bibliography

- An Annotated Critical Bibliography of Henry James by Nicola Bradbury (Harvester Press, 1987). ISBN 978-0710810304

Biography

- Henry James: The Untried Years 1843–1870 by Leon Edel (1953)

- Henry James: The Conquest of London 1870–1881 by Leon Edel (1962) ISBN 0-380-39651-3

- Henry James: The Middle Years 1882–1895 by Leon Edel (1962) ISBN 0-380-39669-6

- Henry James: The Treacherous Years 1895–1901 by Leon Edel (1969) ISBN 0-380-39677-7

- Henry James: The Master 1901–1916 by Leon Edel (1972) ISBN 0-380-39677-7

- Henry James: A Life by Leon Edel (1985) ISBN 0060154594. One-volume abridgment of Edel's five-volume biography, listed above.

- Henry James: The Young Master by Sheldon M. Novick (1996) ISBN 0812978838

- Henry James: The Mature Master by Sheldon M. Novick (2007) ISBN 0679450238

- Henry James: The Imagination of Genius by Fred Kaplan (1992) ISBN 0-688-09021-4

- A Private Life of Henry James: Two Women and His Art by Lyndall Gordon (1998) ISBN 0-393-04711-3. Revised edition titled Henry James: His Women and His Art (2012) ISBN 978-1-84408-892-8.

- House of Wits: An Intimate Portrait of the James Family by Paul Fisher (2008) ISBN 1616793376

- The James Family: A Group Biography by F. O. Matthiessen (0394742435) ISBN 0679450238

Letters

- Theatre and Friendship by Elizabeth Robins. London: Jonathan Cape, 1932.

- Henry James: Letters edited by Leon Edel (four vols. 1974–1984)

- Henry James: A Life in Letters edited by Philip Horne (1999) ISBN 0-670-88563-0

- The Complete Letters of Henry James,1855–1872 edited by Pierre A. Walker and Greg Zacharias (two vols., University of Nebraska Press, 2006)

- The Complete Letters of Henry James, 1872–1876 edited by Pierre A. Walker and Greg W. Zacharias (three vols., University of Nebraska Press, 2008)

Editions

- Complete Stories 1864–1874 (Jean Strouse, ed, Library of America, 1999) ISBN 978-1-883011-70-3

- Complete Stories 1874–1884 (William Vance, ed, Library of America, 1999) ISBN 978-1-883011-63-5

- Complete Stories 1884–1891 (Edward Said, ed, Library of America, 1999) ISBN 978-1-883011-64-2

- Complete Stories 1892–1898 (John Hollander, David Bromwich, Denis Donoghue, eds, Library of America, 1996) ISBN 978-1-883011-09-3

- Complete Stories 1898–1910 (John Hollander, David Bromwich, Denis Donoghue, eds, Library of America, 1996) ISBN 978-1-883011-10-9

- Novels 1871–1880: Watch and Ward, Roderick Hudson, The American, The Europeans, Confidence (William T. Stafford, ed., Library of America, 1983) ISBN 978-0-940450-13-4

- Novels 1881–1886: Washington Square, The Portrait of a Lady, The Bostonians (William T. Stafford, ed, Library of America, 1985) ISBN 978-0-940450-30-1

- Novels 1886–1890: The Princess Casamassima, The Reverberator, The Tragic Muse (Daniel Mark Fogel, ed, Library of America, 1989) ISBN 978-0-940450-56-1

- Novels 1896–1899: The Other House, The Spoils of Poynton, What Maisie Knew, The Awkward Age (Myra Jehlen, ed, Library of America, 2003) ISBN 978-1-931082-30-3

- Novels 1901–1902: The Sacred Fount, The Wings of the Dove (Leo Bersani, ed, Library of America, 2006) ISBN 978-1-931082-88-4

- Collected Travel Writings, Great Britain and America: English Hours; The American Scene; Other Travels edited by Richard Howard (Library of America, 1993) ISBN 978-0-940450-76-9

- Collected Travel Writings, The Continent: A Little Tour in France, Italian Hours, Other Travels edited by Richard Howard (Library of America, 1993) ISBN 0-940450-77-1

- Literary Criticism Volume One: Essays on Literature, American Writers, English Writers edited by Leon Edel and Mark Wilson (Library of America, 1984) ISBN 978-0-940450-22-6

- Literary Criticism Volume Two: French Writers, Other European Writers, The Prefaces to the New York Edition edited by Leon Edel and Mark Wilson (Library of America, 1984) ISBN 978-0-940450-23-3

- The Complete Notebooks of Henry James edited by Leon Edel and Lyall Powers (1987) ISBN 0-19-503782-0

- The Complete Plays of Henry James edited by Leon Edel (1991) ISBN 0195043790

- Henry James: Autobiography edited by F.W. Dupee (1956)

- The American: an Authoritative Text, Backgrounds and Sources, Criticism edited by James Tuttleton (1978) ISBN 0-393-09091-4

- The Ambassadors: An Authoritative Text, The Author on the Novel, Criticism edited by S.P. Rosenbaum (1994) ISBN 0-393-96314-4

- The Turn of the Screw: Authoritative Text, Contexts, Criticism edited by Deborah Esch and Jonathan Warren (1999) ISBN 0-393-95904-X

- The Portrait of a Lady: An Authoritative Text, Henry James and the Novel, Reviews and Criticism edited by Robert Bamberg (2003) ISBN 0-393-96646-1

- The Wings of the Dove: Authoritative Text, The Author and the Novel, Criticism edited by J. Donald Crowley and Richard Hocks (2003) ISBN 0-393-97881-8

- Tales of Henry James: The Texts of the Tales, the Author on His Craft, Criticism edited by Christof Wegelin and Henry Wonham (2003) ISBN 0-393-97710-2

- The Portable Henry James, New Edition edited by John Auchard (2004) ISBN 0-14-243767-0

- Henry James on Culture: Collected Essays on Politics and the American Social Scene edited by Pierre Walker (1999) ISBN 0-8032-2589-X

Criticism

- The Novels of Henry James by Oscar Cargill (1961)

- Henry James: the later novels by Nicola Bradbury (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979)

- The Tales of Henry James by Edward Wagenknecht (1984) ISBN 0-8044-2957-X

- Modern Critical Views: Henry James edited by Harold Bloom (1987) ISBN 0-87754-696-7

- A Companion to Henry James Studies edited by Daniel Mark Fogel (1993) ISBN 0-313-25792-2

- Henry James's Europe: Heritage and Transfer edited by Dennis Tredy, Annick Duperray and Adrian Harding (2011) ISBN 978-1-906924-36-2

- Echec et écriture. Essai sur les nouvelles de Henry James by Annick Duperray (1992)

- Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays edited by Ruth Yeazell (1994) ISBN 0-13-380973-0

- The Cambridge Companion to Henry James edited by Jonathan Freedman (1998) ISBN 0-521-49924-0

- The Novel Art: Elevations of American Fiction after Henry James by Mark McGurl (2001) ISBN 0-691-08899-3

- Henry James and the Visual by Kendall Johnson (2007) ISBN 0-521-88066-1

- False Positions: The Representational Logics of Henry James's Fiction. by Julie Rivkin. (1996) ISBN 0-8047-2617-5

- 'Henry James's Critique of the Beautiful Life,' by R.R. Reno in Azure, Spring 2010,

- Approaches to Teaching Henry James's Daisy Miller and The Turn of the Screw edited by Kimberly C. Reed and Peter G. Beidler (2005) ISBN 0-87352-921-9

- Henry James and Modern Moral Life by Robert B. Pippin (1999) ISBN 0-521-65230-8

- "Friction with the Market": Henry James and the Profession of Authorship by Michael Anesko (1986) ISBN 0-19-504034-1

External links

| Library resources about Henry James |

- The Henry James Scholar's Guide to Web Sites

- The Ladder—a Henry James Web Site (archived)

- Henry James on IMDb

- Finding aid to Henry James letters at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Electronic editions

- Works by Henry James at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Henry James at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Henry James at Internet Archive

- Works by Henry James at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Henry James at Open Library

- The Henry James Collection From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress