Jovan Rajić

Jovan Rajić (Serbian Cyrillic: Јован Рајић; September 21, 1726 – December 22, 1801) was a Serbian writer, historian, traveller, and pedagogue, considered one of the greatest Serbian academics of the 18th century. He was one of the most notable representatives of Serbian Baroque literature along with Zaharije Orfelin, Pavle Julinac, Vasilije III Petrović-Njegoš, Simeon Končarević, Simeon Piščević, and others (although he worked in the first half of 18th century, as Baroque trends in Serbian literature emerged in the late 17th century).

Jovan Rajić | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 21, 1726 Sremski Karlovci, Slavonian Military Frontier, Habsburg Monarchy |

| Died | December 22, 1801 Kovilj |

| Occupation |

|

| Nationality | Serb |

| Literary movement | Baroque |

Rajić was the forerunner to modern Serbian historiography,[1] and has been compared to the importance of Nikolay Karamzin to Russian historiography.[2]

Biography

Rajić was born on September 21, 1726, in Sremski Karlovci. Jovan received his elementary education in his native town, in the school of Deacon Petar Rajkov, a more zealous than learned successor of his own imported Russian teachers, notably Emanuel Kozačinski. It was through Rajkov that young Jovan Rajić would learn Serbian historiography, which belonged to the latter group. He attended Novi Sad's Petrovaradinska roždestveno-bogorodičina škola latinsko-slovenska, the Latino-Slavonic School of Our Lady for young theologians, founded by Visarion Pavlović and where Russian-born academic Emanuel Kozačinski first began teaching in 1731. He also attended the first Serbian chant school, founded by Metropolitan Mojsije Petrović in 1721, where he learned "psalm chants" in Serbian and in Greek. In 1744 he moved to Komárom where he attended a Jesuit gymnasium for four years. Fearing to be converted, he became a student of Protestant lycée in Sopron in 1748. He graduated in 1752 and he was ostensibly headed for the church. But his tastes lead him in a different direction for the time being; not content with a knowledge of books only, he wished to know the world and people better. During a period of almost ten years, he seized every opportunity for profitable travel whenever he could. He travelled on foot from Hungary to Russian Empire – a distance of 800 miles -— where he enrolled as a student of the prestigious Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. He remained in Kiev until 1756 studying theology and liberal arts. He immediately formed a friendship with his professors, many of whom were disciples of Feofan Prokopovich, the great reformer of the Russian Orthodox Church and one of the founders of the Russian Academy of Sciences. After graduating from the Kiev academy he travelled to Moscow and Smolensk. For the next few months, he led an unsettled life, attracting attention everywhere by his talents and boldness of his teaching. On his way home he also visited Poland and various parts of Hungary. In 1757 he returned to his native Sremski Karlovci and sought a teaching position at a seminary called Pokrovo-Bogorodičina škola, which was denied. Dejected and hurt, he decided to go back to Imperial Russia. He arrived in 1757 back in Kiev where he stayed only for a short time. That same year he travelled to Poland, Wallachia, Moldavia before taking a ship across the Black Sea to Constantinople, and from there to Mount Athos, where he spent a few months at the Serbian Monastery of Hilandar, doing research in the library. It wasn't until late 1759 that he became a professor of geography and rhetoric in Pokrovo-Bogorodičina škola in Sremski Karlovci. Entering a conflict with high representatives of Serbian Orthodox Church in Sremski Karlovci, he moved to Temesvar, modern-day Romania. Life at the episcopal residence was luxurious. Though Rajić resisted the evils attendant on such luxury—loose morals, drunkenness, intrigue—he did acquire a vice which was to embitter the rest of his days, avarice. But more important, he found time in Temesvar to work on his History. After a turbulent year and a half, Rajić left for Novi Sad at the invitation of the Serbian Bishop of Bačka, Mojsije Putnik. He was inaugurated rector of the institution of higher learning, Duhovna kolegija, by Metropolitan Pavle Nenadović of the Metropolitanate of Karlovci in 1767. There he stayed for more than four years as both rector and professor of theology. His lectures, in which he endeavoured to show that Orthodox theology is in complete harmony with reason, were received with eager interest by the younger generation of thinkers. His unshakable faith in Reason awakened and inspired his students and thus prepared succeeding generations to traverse paths which were closed to Orfelin and to his Serbian contemporaries. In 1772 he went to Kovilj monastery where, at the age of 46, Rajić became a monk and soon after he was elevated to the monastic rank of archimandrite, and made abbot of the same monastery. He spent the rest of his life in the monastery writing books, mostly with religious and theological themes. In a fruitful lifetime which spanned the last three-quarters of the eighteenth century, Rajić brought Rationalism to its zenith among Serbs in Serbian lands.

He died in the Serbian Kovilj monastery on December 22, 1801.

Works

He wrote in Serbian, Russian, Latin, German, Hungarian and Old Slavonic. He was one of the best educated Serbian ecclesiastical scholars who knew theology and history better than most in his day. He translated the works of Feofan Prokopovich, Peter Mohyla, Platon Levshin, Lazar Baranovych, Metropolitan Gedeon of Kiev, and various German and Hungarian authors. He wrote the history of the Serbian Orthodox Church and a Serbian catechesis for children which was first published in Vienna in 1774 and was consequently reprinted many times over for the next 89 years. He is best remembered for his history books.

All of Rajić's research work came from Russian and Serbian sources, particularly Đorđe Branković's then unpublished, 2,000-page manuscript. He was a most liberal-minded man, both in politics and religion, an enthusiastic supporter of popular education and a most inspiring teacher and speaker. Rajić was always stating that the business of the Eastern Orthodox Church as a whole is not polemic but irenic, operating toward peace, moderation and conciliation. He took great interest in the struggle of the Serbs for independence.

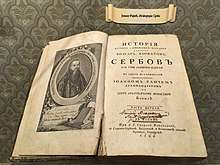

His claim on posterity, however, lies not on his irenical writings alone but in the quality of his literary translations and other writings, exhibited at its best in the four-volume work, published in Vienna and Moscow, "Istorija raznih slavenskih narodov, naipače Bolgar, Horvatov i Serbov (1794-1795)" (The History of various Slavic peoples, particularly the Bulgarians, Croats and Serbs). The Istorija, including the 1795 edition in Moscow that sealed its authority, was bound to the medieval religious historiographical tradition and was influenced by not only Branković's work but also the Russian editions of Caesar Baronius's "Annales Ecclesiastici", Mavro Orbin's "Il regno de gli Slavi" (The Realm of the Slavs), and Charles du Fresne, sieur du Cange's "Illyricum vetus et nuovum" (1746) (Illyrium: Old and New). Rajić's work is divided into four volumes, each sub-divided in three parts dealing respectively with the history of Bulgarians, Croats and Serbs. His intention was to reconstruct the history of the south Slavic peoples as if they were a single entity. He placed at the centre of his research the people and the new historical sensibility that must serve them. The past was re-evaluated from two main perspectives: to preserve Slav history from falling into oblivion; and to save it from a memory imbued with personal events bound to the tradition of dynastic claims. From the preface it can be inferred that Rajić saw history as the basis for other sciences. Also, Rajić paid attention to the Habsburg dynasty and considered them defenders of the Serbs against Turkish oppression. Yet, at the same time, he cautioned them against the Habsburg's attempts of Germanization and conversion to Uniate Catholicism.

Notable works

- Pesni različnina gospodskih prazniki (Vienna, 1790)

- Kant o vospominaniju smrti, cantata

- Boj zmaja s orlovi, (The Battle between Dragon and Eagles) epic poem

- Istorija raznih slovenskih narodov, najpače Bolgar, Horvatov i Serbov (The History of Various Slavic Peoples, especially of Bulgars, Croats and Serbs), the first systematic work on the history of Croats and Serbs, in four volumes

- Serbian Catechesis (Katihisis mali)

- Uroš V (reworked drama by Emanuel Kozačinski, his teacher)[3]

See also

References

- Lucian Boia (January 1, 1989). Great Historians from Antiquity to 1800: An International Dictionary. Greenwood Press. p. 343. ISBN 978-0-313-24517-6.

- University of Colorado (1956). Journal of Central European Affairs. 16. Boulder, Colorado: University of Colorado. p. 23.

- Torlone, Zara Martirosova; Munteanu, Dana Lacourse; Dutsch, Dorota (April 17, 2017). A Handbook to Classical Reception in Eastern and Central Europe. ISBN 9781118832714.

Sources

- Orbini, Mauro (1601). Il Regno de gli Slavi hoggi corrottamente detti Schiavoni. Pesaro: Apresso Girolamo Concordia.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Орбин, Мавро (1968). Краљевство Словена. Београд: Српска књижевна задруга.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jovan Skerlić, Istorija Nove Srpske Književnosti (Belgrade 1921), pp. 50–60.

- Dimitrije Ruvarac (1901). "Arhimandrit Jovan Rajić, 1726-1801". (Public domain)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jovan Rajić. |