British colonization of the Americas

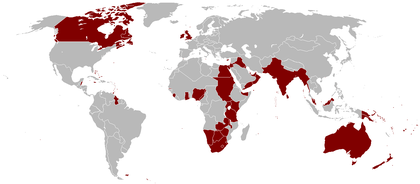

The British colonization of the Americas is the history of the establishment of control, settlement, and decolonization of the continents of the Americas by England, Scotland and (after 1707) Great Britain. Colonization efforts began in the 16th century with failed attempts by England to establish permanent colonies in North America. The first permanent British colony was established in Jamestown, Virginia in 1607. Over the next several centuries more colonies were established in North America, Central America, South America, and the Caribbean. Though most British colonies in the Americas eventually gained independence, some colonies have opted to remain under Britain's jurisdiction as British Overseas Territories.

| Part of a series on |

| European colonization of the Americas |

|---|

.svg.png) |

|

|

North America had been inhabited by people who migrated from Asia for thousands of years prior to 1492. European exploration of North America began with Christopher Columbus's 1492 expedition sponsored by Spain. English exploration began almost a century later. Sir Walter Raleigh established the short-lived Roanoke Colony in 1585. The settlement of Jamestown grew into the Colony of Virginia. In 1620, a group of Puritans established a second permanent colony on the coast of Massachusetts. Several other English colonies were established in North America during the 17th and 18th centuries. With the authorization of a royal charter, the Hudson's Bay Company established the territory of Rupert's Land in the Hudson Bay drainage basin. The English also established or conquered several colonies in the Caribbean, including Barbados and Jamaica.

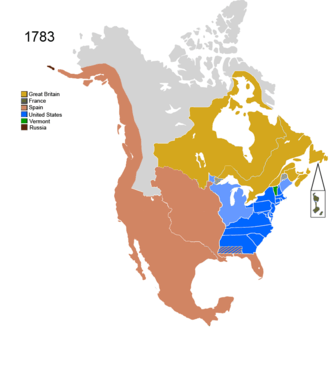

England captured the Dutch colony of New Netherland in the Anglo-Dutch Wars of the mid-17th century, leaving North America divided among the English, Spanish, and French empires. After decades of warring with France, Britain took control of the French colony of Canada, as well as several Caribbean territories, in 1763. With the assistance of France and Spain, many of the North American colonies gained independence from Britain through victory in the American Revolutionary War, which ended in 1783. Historians refer to the British Empire after 1783 as the "Second British Empire"; this period saw Britain increasingly focus on Asia and Africa instead of the Americas, and increasingly focus on the expansion of trade rather than territorial possessions. Nonetheless, Britain continued to colonize parts of the Americas in the 19th century, taking control of British Columbia and establishing the colonies of the Falkland Islands and British Honduras. Britain also gained control of several colonies, including Trinidad and British Guiana, following the 1815 defeat of France in the Napoleonic Wars.

In the mid-19th century, Britain began the process of granting self-government to its remaining colonies in North America. Most of these colonies joined the Confederation of Canada in the 1860s or 1870s, though Newfoundland would not join Canada until 1949. Canada gained full autonomy following the passage of the Statute of Westminster 1931, though it retained various ties to Britain and still recognizes the British monarch as head of state. Following the onset of the Cold War most of the remaining British colonies in the Americas gained independence between 1962 and 1983. Many of the former British colonies are part of the Commonwealth of Nations, a political association chiefly consisting of former colonies of the British Empire.

Background: early exploration and colonization of the Americas

Following the first voyage of Christopher Columbus in 1492, Spain and Portugal established colonies in the New World, beginning the European colonization of the Americas.[1] France and England, the two other major powers of 15th-century Western Europe, employed explorers soon after the return of Columbus's first voyage. In 1497, King Henry VII of England dispatched an expedition led by John Cabot to explore the coast of North America, but the lack of precious metals or other riches discouraged both the Spanish and English from permanently settling in North America during the early 16th century.[2] Later explorers such as Martin Frobisher and Henry Hudson sailed to the New World in search of a Northwest Passage between the Atlantic Ocean and Asia, but were unable to find a viable route.[3] Europeans established fisheries in the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, and traded metal, glass, and cloth for food and fur, beginning the North American fur trade.[4] During mid-1585 Bernard Drake launched an expedition to Newfoundland which crippled the Spanish and Portuguese fishing fleets there from which they never recovered. This would have consequences in terms of English colonial expansion and settlement. Meanwhile, in the Caribbean Sea, English sailors defied Spanish trade restrictions and preyed on Spanish treasure ships.[5]

In the late sixteenth century, Protestant England became embroiled in a religious war with Catholic Spain. Seeking to weaken Spain's economic and military power, English privateers such as Francis Drake and Humphrey Gilbert harassed Spanish shipping.[6] Gilbert proposed the colonization of North America on the Spanish model, with the goal of creating a profitable English empire that could also serve as a base for the privateers. After Gilbert's death, Walter Raleigh took up the cause of North American colonization, sponsoring an expedition of 500 men to Roanoke Island. In 1584, the colonists established the first permanent English colony in North America,[7] but the colonists were poorly prepared for life in the New World, and by 1590, the colonists had disappeared.[8] A separate colonization attempt in Newfoundland also failed.[9] Despite the failure of these early colonies, the English remained interested in the colonization of North America for economic and military reasons.[10]

Early colonization, 1607–1630

In 1606, King James I of England granted charters to both the Plymouth Company and the London Company for the purpose of establishing permanent settlements in North America. In 1607, the London Company established a permanent colony at Jamestown on the Chesapeake Bay, but the Plymouth Company's Popham Colony proved short-lived. The colonists at Jamestown faced extreme adversity, and by 1617 there were only 351 survivors out of the 1700 colonists who had been transported to Jamestown.[11] After the Virginians discovered the profitability of growing tobacco, the settlement's population boomed from 400 settlers in 1617 to 1240 settlers in 1622. The London Company was bankrupted in part due to frequent warring with nearby American Indians, leading the English crown to take direct control of the Colony of Virginia, as Jamestown and its surrounding environs became known.[12] In 1609, an English ship traveling to Virginia wrecked off the shores of the island of Bermuda; though the crew was eventually rescued, England subsequently colonized Bermuda and established the Town of St. George.[13] Between the late 1610s and the American Revolution, the British shipped an estimated 50,000 to 120,000 convicts to their American colonies.[14]

Meanwhile, the Plymouth Council for New England sponsored several colonization projects, including a colony established by a group of English Puritans, known today as the Pilgrims.[15] The Puritans embraced an intensely emotional form of Calvinist Protestantism and sought independence from the Church of England.[16] In 1620, the Mayflower transported the Pilgrims across the Atlantic, and the Pilgrims established Plymouth Colony in Cape Cod. The Pilgrims endured an extremely hard first winter, with roughly fifty of the one hundred colonists dying. In 1621, Plymouth Colony was able to establish an alliance with the nearby Wampanoag tribe, which helped the Plymouth Colony adopt effective agricultural practices and engaged in the trade of fur and other materials.[17] Farther north, the English also established Newfoundland Colony, which primarily focused on cod fishing.[18]

The Caribbean would provide some of England's most important and lucrative colonies,[19] but not before several attempts at colonization failed. An attempt to establish a colony in Guiana in 1604 lasted only two years, and failed in its main objective to find gold deposits.[20] Colonies in St Lucia (1605) and Grenada (1609) also rapidly folded.[21] Encouraged by the success of Virginia, in 1627 King Charles I granted a charter to the Barbados Company for the settlement of the uninhabited Caribbean island of Barbados. Early settlers failed in their attempts to cultivate tobacco, but found great success in growing sugar.[19]

Growth, 1630–1689

West Indies colonies

The success of colonization efforts in Barbados encouraged the establishment of more Caribbean colonies, and by 1660 England had established Caribbean sugar colonies in St. Kitts, Antigua, Nevis, and Montserrat,[19] English colonization of the Bahamas began in 1648 after a Puritan group known as the Eleutheran Adventurers established a colony on the island of Eleuthera. England established another sugar colony in 1655 following the successful invasion of Jamaica during the Anglo-Spanish War.[22] Spain acknowledged English possession of Jamaica and the Caiman Islands in the 1670 Treaty of Madrid. England captured Tortola from the Dutch in 1670, and subsequently took possession of the nearby islands of Anegada and Virgin Gorda; these islands would later form the British Virgin Islands. During the 17th century, the sugar colonies adopted the system of sugar plantations successfully used by the Portuguese in Brazil, which depended on slave labour.[23] Until the abolition of its slave trade in 1807, Britain was responsible for the transportation of 3.5 million African slaves to the Americas, a third of all slaves transported across the Atlantic.[24] Many of the slaves were captured by the Royal African Company in West Africa, though others came from Madagascar.[25] These slaves soon came to form the majority of the population in Caribbean colonies like Barbados and Jamaica, where strict slave codes were established partly to deter slave rebellions.[26]

Establishment of the Thirteen Colonies

New England Colonies

Following the success of the Jamestown and Plymouth Colonies, several more English groups established colonies in the region that became known as New England. In 1629, another group of Puritans led by John Winthrop established the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and by 1635 roughly ten thousand English settlers lived in the region between the Connecticut River and the Kennebec River.[27] After defeating the Pequot in the Pequot War, Puritan settlers established the Connecticut Colony in the region the Pequots had formerly controlled.[28] The Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations was founded by Roger Williams, a Puritan leader who was expelled from the Massachusetts Bay Colony after he advocated for a formal split with the Church of England.[29] As New England was a relatively cold and infertile region, the New England Colonies relied on fishing and long-distance trade to sustain the economy.[30]

Southern Colonies

In 1632, Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore founded the Province of Maryland to the north of Virginia.[31] Maryland and Virginia became known as the Chesapeake Colonies, and experienced similar immigration and economic activities.[32] Though Baltimore and his descendants intended for the colony to be a refuge for Catholics, it attracted mostly Protestant immigrants, many of whom scorned the Calvert family's policy of religious toleration.[33] In the mid-17th century, the Chesapeake Colonies, inspired by the success of slavery in Barbados, began the mass importation of African slaves. Though many early slaves eventually gained their freedom, after 1662 Virginia adopted policies that passed enslaved status from mother to child and granted slave owners near-total domination of their human property.[34]

Encouraged by the apparent weakness of Spanish rule in Florida, Barbadian planter John Colleton and seven other supporters of Charles II of England established the Province of Carolina in 1663.[35] Settlers in the Carolina Colony established two main population centers, with many Virginians settling in the north of the province and many English Barbadians settling in the southern port city of Charles Town.[36] In 1729, following the Yamasee War, Carolina was divided into the crown colonies of North Carolina and South Carolina.[37] The colonies of Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina (as well as the Province of Georgia, which was established in 1732) became known as the Southern Colonies.

Middle Colonies

.jpg)

Beginning in 1609, Dutch traders had established fur trading posts on the Hudson River, Delaware River, and Connecticut River, ultimately creating the Dutch colony of New Netherland, with a capital at New Amsterdam.[38] In 1657, New Netherland expanded through conquest of New Sweden, a Swedish colony centered in the Delaware Valley.[39] Despite commercial success, New Netherland failed to attract the same level of settlement as the English colonies.[40] In 1664, during a series of wars between the English and Dutch, English soldier Richard Nicolls captured New Netherland.[41] The Dutch briefly re-gained control of parts of New Netherland in the Third Anglo-Dutch War, but surrendered its claim to the territory in the 1674 Treaty of Westminster, ending the Dutch colonial presence in North America.[42] In 1664, the Duke of York, later known as James II of England, was granted control of the English colonies north of the Delaware River. He created the Province of New York out of the former Dutch territory and renamed New Amsterdam as New York City.[43] He also created the provinces of West Jersey and East Jersey out of former Dutch land situated to the west of New York City, giving the territories to John Berkeley and George Carteret.[44] East Jersey and West Jersey would later be unified as the Province of New Jersey in 1702.[45]

Charles II rewarded William Penn, the son of distinguished Admiral William Penn, with the land situated between Maryland and the Jerseys. Penn named this land the Province of Pennsylvania.[46] Penn was also granted a lease to the Delaware Colony, which gained its own legislature in 1701.[47] A devout Quaker, Penn sought to create a haven of religious toleration in the New World.[47] Pennsylvania attracted Quakers and other settlers from across Europe, and the city of Philadelphia quickly emerged as a thriving port city.[48] With its fertile and cheap land, Pennsylvania became one of the most attractive destinations for immigrants in the late 17th century.[49] New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware became known as the Middle Colonies.[50]

Hudson's Bay Company

In 1670, Charles II incorporated by royal charter the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), granting it a monopoly on the fur trade in the area known as Rupert's Land. Forts and trading posts established by the HBC were frequently the subject of attacks by the French.[51]

Darien scheme

In 1695, the Parliament of Scotland granted a charter to the Company of Scotland, which established a settlement in 1698 on the Isthmus of Panama. Besieged by neighbouring Spanish colonists of New Granada, and afflicted by malaria, the colony was abandoned two years later. The Darien scheme was a financial disaster for Scotland—a quarter of Scottish capital[52] was lost in the enterprise—and ended Scottish hopes of establishing its own overseas empire. The episode also had major political consequences, persuading the governments of both England and Scotland of the merits of a union of countries, rather than just crowns.[53] This occurred in 1707 with the Treaty of Union, establishing the Kingdom of Great Britain.

Expansion and Conflict, 1689–1763

Settlement and expansion in North America

After succeeding his brother in 1685, King James II and his lieutenant, Edmund Andros, sought to assert the crown's authority over colonial affairs.[54] James was deposed by the new joint monarchy of William and Mary in the Glorious Revolution,[55] but William and Mary quickly reinstated many of the James's colonial policies, including the mercantilist Navigation Acts and the Board of Trade.[56] The Massachusetts Bay Colony, Plymouth Colony and the Province of Maine were incorporated into the Province of Massachusetts Bay, and New York and the Massachusetts Bay Colony were reorganized as royal colonies, with a governor appointed by the king.[57] Maryland, which had experienced a revolution against the Calvert family, also became a royal colony, though the Calverts retained much of their land and revenue in the colony.[58] Even those colonies that retained their charters or proprietors were forced to assent to much greater royal control than had existed before the 1690s.[59]

Between immigration, the importation of slaves, and natural population growth, the colonial population in British North America grew immensely in the 18th century. According to historian Alan Taylor, the population of the Thirteen Colonies (the British North American colonies which would eventually form the United States) stood at 1.5 million in 1750.[60] More than ninety percent of the colonists lived as farmers, though cities like Philadelphia, New York, and Boston flourished.[61] With the defeat of the Dutch and the imposition of the Navigation Acts, the British colonies in North America became part of global British trading network. The colonists traded foodstuffs, wood, tobacco, and various other resources for Asian tea, West Indian coffee, and West Indian sugar, among other items.[62] Native Americans far from the Atlantic coast supplied the Atlantic market with beaver fur and deerskins, and sought to preserve their independence by maintaining a balance of power between the French and English.[63] By 1770, the economic output of the Thirteen Colonies made up forty percent of the gross domestic product of the British Empire.[64]

Prior to 1660, almost all immigrants to the English colonies of North America had migrated freely, though most paid for their passage by becoming indentured servants.[65] Improved economic conditions and an easing of religious persecution in Europe made it increasingly difficult to recruit labor to the colonies in the 17th and 18th centuries. Partly due to this shortage of free labor, the population of slaves in British North America grew dramatically between 1680 and 1750; the growth was driven by a mixture of forced immigration and the reproduction of slaves.[66] In the Southern Colonies, which relied most heavily on slave labor, the slaves supported vast plantation economies lorded over by increasingly wealthy elites.[67] By 1775, slaves made up one-fifth of the population of the Thirteen Colonies but less than ten percent of the population of the Middle Colonies and New England Colonies.[68] Though a smaller proportion of the English population migrated to British North America after 1700, the colonies attracted new immigrants from other European countries,[69] including Catholic settlers from Ireland[70] and Protestant Germans.[71] As the 18th century progressed, colonists began to settle far from the Atlantic coast. Pennsylvania, Virginia, Connecticut, and Maryland all lay claim to the land in the Ohio River valley, and the colonies engaged in a scramble to expand west.[72]

Conflicts with the French and Spanish

The Glorious Revolution and the succession of William III, who had long resisted French hegemony as the Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic, ensured that England and its colonies would come into conflict with the French empire of Louis XIV after 1689.[73] Under the leadership of Samuel de Champlain, the French had established Quebec City on the St Lawrence River in 1608, and it became the center of French colony of Canada.[74] France and England engaged in a proxy war via Native American allies during and after the Nine Years' War, while the powerful Iroquois declared their neutrality.[75] War between France and England continued in Queen Anne's War, the North American component of the larger War of the Spanish Succession. In the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, which ended the War of Spanish Succession, the British won possession of the French territories of Newfoundland and Acadia, the latter of which was renamed Nova Scotia.[30] In the 1730s, James Oglethorpe proposed that the area south of the Carolinas be colonized to provide a buffer against Spanish Florida, and he was part of a group of trustees that were granted temporary proprietorship over the Province of Georgia. Oglethorpe and his compatriots hoped to establish a utopian colony that banned slavery, but by 1750 the colony remained sparsely populated, and Georgia became a crown colony in 1752.[76]

In 1754, the Ohio Company started to build a fort at the confluence of the Allegheny River and the Monongahela River. A larger French force initially chased the Virginians away, but was forced to retreat after the Battle of Jumonville Glen.[77] After reports of the battle reached the French and British capitals, the Seven Years' War broke out in 1756; the North American component of this war is known as the French and Indian War.[78] After the Duke of Newcastle returned to power as Prime Minister in 1757, he and his foreign minister, William Pitt, devoted unprecedented financial resources to the transoceanic conflict.[79] The British won a series of victories after 1758, conquering much of New France by the end of 1760. Spain entered the war on France's side in 1762 and promptly lost several American territories to Britain.[80] The 1763 Treaty of Paris ended the war, and France surrendered almost all of the portion of New France to the east of the Mississippi River to the British. France separately ceded its lands west of the Mississippi River to Spain, and Spain ceded Florida to Britain.[81] With the newly acquired territories, the British created the provinces of East Florida, West Florida, and Quebec, all of which were placed under military governments.[82] In the Caribbean, Britain retained Grenada, St. Vincent, Dominica, and Tobago, but returned control of Martinique, Havana, and other colonial possessions to France or Spain.[83]

The Americans break away, 1763–1783

The British subjects of North America believed the unwritten British constitution protected their rights and that the governmental system, with the House of Commons, the House of Lords, and the monarch sharing power found an ideal balance among democracy, oligarchy, and tyranny.[84] However, the British were saddled with huge debts following the French and Indian War. As much of the British debt had been generated by the defense of the colonies, British leaders felt that the colonies should contribute more funds, and they began imposing taxes such as the Sugar Act of 1764.[85] Increased British control of the Thirteen Colonies upset the colonists and upended the notion many colonists held: that they were equal partners in the British Empire.[86] Meanwhile, seeking to avoid another expensive war with Native Americans, Britain issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which restricted settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains. However it was effectively replaced five years later thanks to the Treaty of Fort Stanwix.[87] The Thirteen Colonies became increasingly divided between Patriots opposed to Parliamentary taxation without representation, Loyalists who supported the king. In the British colonies nearest to the Thirteen Colonies, however, protests were muted, as most colonists accepted the new taxes. These provinces had smaller populations, were largely dependent on the British military, and had less of a tradition of self-rule.[88]

At the Battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775, the Patriots repulsed a British force charged with seizing militia arsenals.[89] The Second Continental Congress assembled in May 1775 and sought to coordinate armed resistance to Britain. It established an impromptu government that recruited soldiers and printed its own money. Announcing a permanent break with Britain, the delegates adopted a Declaration of Independence on 4 July 1776 for the United States of America.[90] The French formed a military alliance with the United States in 1778 following the British defeat at the Battle of Saratoga. Spain joined France in order to regain Gibraltar from Britain.[91] A combined Franco-American operation trapped a British invasion army at Yorktown, Virginia, forcing it surrender in October 1781.[92] The surrender shocked Britain. The king wanted to keep fighting but he lost control of Parliament and peace negotiations began.[93] In the 1783 Treaty of Paris, Britain ceded all of its North American territory south of the Great Lakes, except for the two Florida colonies, which were ceded to Spain.[94] Having defeated a combined Franco-Spanish naval force at the decisive 1782 Battle of the Saintes, Britain retained control of Gibraltar and all its pre-war Caribbean possessions except for Tobago.[95] Economically the new nation became a major trading partner of Britain.

Second British Empire, 1783–1945

The loss of a large portion of British America defined the transition between the "first" and "second" empires, in which Britain shifted its attention away from the Americas to Asia, the Pacific, and later Africa.[96] Influenced by the ideas of Adam Smith, Britain also shifted away from mercantile ideals and began to prioritize the expansion of trade rather than territorial possessions.[97] During the nineteenth century, some observers described Britain as having an "unofficial" empire based on the export of goods and financial investments around the world, including the newly independent republics of Latin America. Though this unofficial empire did not require direct British political control, it often involved the use of gunboat diplomacy and military intervention to protect British investments and ensure the free flow of trade.[98]

From 1793 to 1815, Britain was almost constantly at war, first in the French Revolutionary Wars and then in the Napoleonic Wars.[99] During the wars, Britain took control of many French, Spanish, and Dutch Caribbean colonies.[100] Tensions between Britain and the United States escalated during the Napoleonic Wars, as Britain tried to cut off American trade with France and boarded American ships to impress men into the Royal Navy. After the largely inconclusive War of 1812, the pre-war boundaries were reaffirmed by the 1814 Treaty of Ghent, ensuring Canada's future would be separate from that of the United States.[101] Following the final defeat of French Emperor Napoleon in 1815, Britain gained ownership of Trinidad, Tobago, British Guiana, and Saint Lucia, as well as other territories outside of the Western Hemisphere.[102] The Treaty of 1818 with the United States set a large portion of the Canada–United States border at the 49th parallel and also established a joint U.S.–British occupation of Oregon Country.[103] In the 1846 Oregon Treaty, the United States and Britain agreed to split Oregon Country along the 49th parallel north with the exception of Vancouver Island, which was assigned in its entirety to Britain.

After warring throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in both Europe and the Americas, the British and French reached a lasting peace after 1815. Britain would fight only one war (the Crimean War) against a European power during the remainder of the nineteenth century, and that war did not lead to territorial changes in the Americas.[104] However, the British Empire continued to engage in wars such as the First Opium War against China; it also put down rebellions such as the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the Canadian Rebellions of 1837–1838, and the Jamaican Morant Bay rebellion of 1865.[105] A strong abolition movement had emerged in the United Kingdom in the late-eighteenth century, and Britain abolished the slave trade in 1807.[106] In the mid-nineteenth century, the economies of the British Caribbean colonies would suffer as a result of the Slavery Abolition Act 1833, which abolished slavery throughout the British Empire, and the 1846 Sugar Duties Act, which ended preferential tariffs for sugar imports from the Caribbean.[107] To replace the labor of former slaves, British plantations on Trinidad and other parts of the Caribbean began to hire indentured servants from India and China.[108]

Establishing the Dominion of Canada

Despite its defeat in the American Revolutionary War and shift towards a new form of imperialism during the nineteenth century,[96][97] the British Empire retained numerous colonies in the Americas after 1783. During and after the American Revolutionary War, between 40,000 and 100,000 defeated Loyalists migrated from the United States to Canada.[109] The 14,000 Loyalists who went to the Saint John and Saint Croix river valleys, then part of Nova Scotia, felt too far removed from the provincial government in Halifax, so London split off New Brunswick as a separate colony in 1784.[110] The Constitutional Act of 1791 created the provinces of Upper Canada (mainly English-speaking) and Lower Canada (mainly French-speaking) to defuse tensions between the French and British communities, and implemented governmental systems similar to those employed in Britain, with the intention of asserting imperial authority and not allowing the sort of popular control of government that was perceived to have led to the American Revolution.[111]

In response to the Rebellions of 1837–1838,[111] Britain passed the Act of Union in 1840, which united Upper Canada and Lower Canada into the Province of Canada. Responsible government was first granted to Nova Scotia in 1848, and was soon extended to the other British North American colonies. With the passage of the British North America Act, 1867 by the British Parliament, Upper and Lower Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia were formed into the confederation of Canada.[112] Rupert's Land (which was divided into Manitoba and the Northwest Territories), British Columbia, and Prince Edward Island joined Canada by the end of 1873, but Newfoundland would not join Canada until 1949. Like other British dominions such as Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa, Canada enjoyed autonomy over its domestic affairs but recognized the British monarch as head of state and cooperated closely with Britain on defense issues.[113] After the passage of the 1931 Statute of Westminster,[114] Canada and other dominions were fully independent of British legislative control; they could nullify British laws and Britain could no longer pass laws for them without their consent.[115]

British Honduras and Falkland Islands

In the early 17th century, English sailors had begun cutting logwood in parts of coastal Central America over which the Spanish exercised little control. By the early 18th century, a small British settlement had been established on the Belize River, though the Spanish refused to recognize British control over the region and frequently evicted British settlers. In the 1783 Treaty of Paris and the 1786 Convention of London, Spain gave Britain the right to cut logwood and mahogany in the area between the Hondo River and the Belize River, but Spain retained sovereignty over this area. Following the 1850 Clayton–Bulwer Treaty with the United States, Britain agreed to evacuate its settlers from the Bay Islands and the Mosquito Coast, but it retained control of the settlement on the Belize River. In 1862, Britain established the crown colony of the British Honduras at this location.[116]

The British first established a presence on the Falkland Islands in 1765 but were compelled to withdraw for economic reasons related to the American War of Independence in 1774.[117] The islands continued to be used by British sealers and whalers, although the settlement of Port Egmont was destroyed by the Spanish in 1780. Argentina attempted to establish a colony in the ruins of the former Spanish settlement of Puerto Soledad, which ended with the British return in 1833. The British governed the uninhabited South Georgia Island, which had been claimed by Captain James Cook in 1775, as a dependency of the Falkland Islands.[118]

Decolonization and overseas territories, 1945-present

Successful independence movements

With the onset of the Cold War in the late 1940s, the British government began to assemble plans for the independence of the empire's colonies in Africa, Asia, and the Americas. British authorities initially planned for a three-decades-long process in which each colony would develop a self-governing and democratic parliament, but unrest and fears of Communist infiltration in the colonies encouraged the British to speed up the move towards self-governance.[119] Compared to other European empires, which experienced wars of independence such as the Algerian War and the Portuguese Colonial War, the British post-war process of decolonization in the Caribbean and elsewhere was relatively peaceful.[120]

In an attempt to unite its Caribbean colonies, Britain established the West Indies Federation in 1958. The federation collapsed following the loss of its two largest members, Jamaica and Trinidad, each of which attained independence in 1962; Trinidad formed a union with Tobago to become the country of Trinidad and Tobago.[121] The eastern Caribbean islands, as well as the Bahamas, gained independence in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.[121] Guyana achieved independence in 1966. Britain's last colony on the American mainland, British Honduras, became a self-governing colony in 1964 and was renamed Belize in 1973, achieving full independence in 1981. A dispute with Guatemala over claims to Belize was left unresolved.[122]

Remaining territories

Though many of the Caribbean territories of the British Empire gained independence, Anguilla and the Turks and Caicos Islands opted to revert to British rule after they had already started on the path to independence.[123] The British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, Montserrat, and the Falkland Islands also remain under the jurisdiction of Britain.[124] In 1982, Britain defeated Argentina after in the Falklands War, an undeclared war in which Argentina attempted to seize control of the Falkland Islands.[125] In 1983, the British Nationality Act 1981 renamed the existing Crown Colonies as "British Dependent Territories", and in 2002 they were renamed the British Overseas Territories.[126] The eleven inhabited territories are self-governing to varying degrees and are reliant on the UK for foreign relations and defence.[127] Most former British colonies and protectorates are among the 52 member states of the Commonwealth of Nations, a non-political, voluntary association of equal members, comprising a population of around 2.2 billion people.[128] Sixteen Commonwealth realms, including Canada and several countries in the Caribbean, voluntarily continue to share the British monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, as their head of state.[129]

List of colonies

Former North American colonies

Canadian territories

These colonies and territories became part of Canada between 1867 and 1873 unless otherwise noted:

- British Columbia

- Province of Canada (formed from the merger of Upper Canada and Lower Canada in 1841)

- Nova Scotia

- New Brunswick

- Dominion of Newfoundland (became part of Canada in 1949)

- Prince Edward Island

- Rupert's Land (became part of Canada as Manitoba and the Northwest Territories)

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, which became the original states of the United States following the 1781 ratification of the Articles of Confederation:

- Province of Massachusetts Bay

- Province of New Hampshire

- Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations

- Connecticut Colony

- Province of New York

- Province of New Jersey

- Province of Pennsylvania

- Delaware Colony

- Province of Maryland

- Colony of Virginia

- Province of North Carolina

- Province of South Carolina

- Province of Georgia

Other North American colonies

These colonies were acquired in 1763 and ceded to Spain in 1783:

- Province of East Florida (from Spain, retroceded to Spain)

- Province of West Florida (from France as part of eastern French Louisiana, ceded to Spain)

Former colonies in the Caribbean and South America

These present-day countries formed part of the British West Indies prior to gaining independence during the 20th century:

- Antigua and Barbuda (gained independence in 1981)

- The Bahamas (gained independence in 1973)

- Barbados (gained independence in 1966)

- Belize (gained independence in 1981; formerly known as British Honduras)

- Dominica (gained independence in 1978)

- Grenada (gained independence in 1974)

- Guyana (gained independence in 1966; formerly known as British Guiana)

- Jamaica (gained independence in 1962)

- Saint Kitts and Nevis (gained independence in 1983)

- Saint Lucia (gained independence in 1979)

- Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (gained independence in 1979)

- Trinidad and Tobago (gained independence in 1962)

Current territories

These British Overseas Territories in the Americas remain under the jurisdiction of the United Kingdom:

See also

Notes

References

- Richter (2011), pp. 69-70

- Richter (2011), pp. 83-85

- Richter (2011), pp. 121-123

- Richter (2011), pp. 129-130

- James (1997), pp. 16–17

- Richter (2011), pp. 98-100

- Richter (2011), pp. 100-102

- Richter (2011), pp. 103-107

- James (1997), p. 5

- Richter (2011), p. 112

- Richter (2011), pp. 113-115

- Richter (2011), pp. 116-117

- "Bermuda - History and Heritage". Smithsonian.com. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- James Davie Butler, "British Convicts Shipped to American Colonies," American Historical Review (1896) 2#1 pp. 12–33 in JSTOR; Thomas Keneally, The Commonwealth of Thieves, Random House Publishing, Sydney, 2005.

- Richter (2011), pp. 152-153

- Richter (2011), pp. 178-179

- Richter (2011), pp. 153-157

- James (1997), pp. 7–8

- James (1997), p. 17

- Canny (1998), p. 71

- Canny (1998), p. 221

- James (1997), pp. 30–31

- Lloyd (1996), pp. 22–23.

- Ferguson (2004), p. 62

- James (1997), p. 24

- James (1997), pp. 42–43

- Richter (2011), pp. 157-159

- Richter (2011), pp. 161-167

- Richter (2011), pp. 196-197

- Taylor (2016), p. 19

- Richter (2011), pp. 262-263

- Richter (2011), pp. 203-204

- Richter (2011), pp. 303-304

- Richter (2011), p. 272

- Richter (2011), pp. 236-238

- Richter (2011), p. 319

- Richter (2011), pp. 323-324

- Richter (2011), pp. 138-140

- Richter (2011), p. 262

- Richter (2011), pp. 215-217

- Richter (2011), pp. 248-249

- Richter (2011), p. 261

- Richter (2011), pp. 247-249

- Richter (2011), pp. 249-251

- Richter (2011), pp. 252-253

- Richter (2011), p. 373

- Richter (2011), p. 251

- Richter (2011), pp. 357

- Richter (2011), pp. 358

- McCusker, John J.; Menard, Russell R. (1991). The Economy of British America, 1607-1789. University of North Carolina Press. doi:10.5149/9781469600000_mccusker.16 (inactive 21 May 2020). JSTOR 10.5149/9781469600000_mccusker.

- Bucker (2008), p. 25

- Magnusson (2003), p. 531

- Macaulay (1848), p. 509

- Richter (2011), pp. 290-294

- Richter (2011), pp. 300-301

- Richter (2011), pp. 310-311, 328

- Richter (2011), pp. 314-315

- Richter (2011), p. 315

- Richter (2011), pp. 315-316

- Taylor (2016), p. 20

- Taylor (2016), p. 23

- Richter (2011), pp. 329-330

- Richter (2011), pp. 332-336

- Taylor (2016), p. 25

- James (1997), pp. 10–11

- Richter (2011), pp. 346-347

- Richter (2011), pp. 346–347, 351-352

- Taylor (2016), p. 21

- Taylor (2016), pp. 18-19

- Richter (2011), pp. 360

- Richter (2011), pp. 362

- Richter (2011), pp. 373-374

- Richter (2011), pp. 296-298

- Richter (2011), pp. 130-135

- Richter (2011), pp. 317-318

- Richter (2011), pp. 358-359

- Richter (2011), pp. 385-387

- Richter (2011), pp. 388-389

- Taylor (2016), p. 45

- Richter (2011), pp. 396-398

- Richter (2011), pp. 406-407

- Richter (2011), pp. 407-409

- James (1997), p. 76

- Taylor (2016), pp. 31-35

- Taylor (2016), pp. 51-53, 94–96

- Taylor (2016), pp. 51-52

- Taylor (2016), pp. 60-61

- Taylor (2016), pp. 102-103, 137-138.

- Taylor (2016), pp. 132-133

- Taylor (2016), pp. pp. 139-141, 160-161

- Taylor (2016), pp. 187-191

- Taylor (2016), pp. 293-295

- Taylor (2016), pp. 295-297

- Taylor (2016), pp. 306-308

- James (1997), pp. 80–82

- Canny (1998), p. 92

- James (1997), pp. 119–121, 165

- James (1997), pp. 173–174, 177

- James (1997), p. 151

- James (1997), p. 154

- Jeremy Black, The War of 1812 in the Age of Napoleon (2009) pp 204–37.

- James (1997), p. 165

- "James Monroe: Foreign Affairs". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. 4 October 2016. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- James (1997), pp. 179–182

- James (1997), pp. 190, 193

- James (1997), pp. 185–186

- James (1997), pp. 171–172

- James (1997), p. 188

- Zolberg (2006), p. 496

- Kelley & Trebilcock (2010), p. 43

- Smith (1998), p. 28

- Porter (1998), p. 187

- James (1997), pp. 311–312, 341

- Rhodes, Wanna & Weller (2009), pp. 5–15

- Turpin & Tomkins, p. 48

- Bolland, Nigel. "Belize: Historical Setting". In A Country Study: Belize (Tim Merrill, editor). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (January 1992).

- Gibran, Daniel (1998). The Falklands War: Britain Versus the Past in the South Atlantic. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-7864-0406-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- R.K. Headland, The Island of South Georgia, Cambridge University Press, 1984. ISBN 0-521-25274-1

- James (1997), p. 538–539

- James (1997), pp. 588–589

- Knight & Palmer (1989), pp. 14–15.

- Lloyd (1996), pp. 401, 427–29.

- Clegg (2005), p. 128.

- James (1997), p. 622

- James (1997), pp. 624–626

- House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee Overseas Territories Report, pp. 145–47

- House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee Overseas Territories Report, pp. 146,153

- The Commonwealth – About Us Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine; Online September 2014

- "Head of the Commonwealth". Commonwealth Secretariat. Archived from the original on 6 July 2010. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

Works cited

- Anderson, Fred (2000). The Crucible of War. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0375406423.

- Anderson, Fred (2005). The War That Made America. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0670034543.

- Bailyn, Bernard (2012). The Barbarous Years: The Peopling of British North America--The Conflict of Civilizations, 1600-1675. Knopf.

- Black, Jeremy. The War of 1812 in the Age of Napoleon (2009).

- Buckner, Phillip (2008). Canada and the British Empire. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927164-1. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- Canny, Nicholas (1998). The Origins of Empire: British Overseas Enterprise to the Close of the Seventeenth Century. Oxford University Press.

- Chandler, Ralph Clark (Winter 1990). "Public Administration Under the Articles of Confederation". Public Administration Quarterly. 13 (4): 433–450. JSTOR 40862257.

- Clegg, Peter (2005). "The UK Caribbean Overseas Territories". In de Jong, Lammert; Kruijt, Dirk (eds.). Extended Statehood in the Caribbean. Rozenberg Publishers. ISBN 978-90-5170-686-4.

- Ferguson, Niall (2004). Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02329-5.

- Ferling, John (2003). A Leap in the Dark: The Struggle to Create the American Republic. Oxford University Press.

- Horn, James (2011). A Kingdom Strange: The Brief and Tragic History of the Lost Colony of Roanoke. Philadelphia: Basic Book. ISBN 978-0465024902.

- Kelley, Ninette; Trebilcock, Michael (2010). The Making of the Mosaic (2nd ed.). University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-9536-7.

- Knight, Franklin W.; Palmer, Colin A. (1989). The Modern Caribbean. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1825-1.

- James, Lawrence (1997). The Rise and Fall of the British Empire. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 9780312169855.

- Lloyd, Trevor Owen (1996). The British Empire 1558–1995. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-873134-4.

- Macaulay, Thomas (1848). The History of England from the Accession of James the Second. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-043133-9.

- Magnusson, Magnus (2003). Scotland: The Story of a Nation. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-3932-0. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- Middlekauff, Robert (2005). The Glorious Cause: the American Revolution, 1763-1789. Oxford University Press.

- Porter, Andrew (1998). The Nineteenth Century, The Oxford History of the British Empire Volume III. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-924678-6. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- Rhodes, R.A.W.; Wanna, John; Weller, Patrick (2009). Comparing Westminster. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-956349-4.

- Richter, Daniel (2011). Before the Revolution : America's ancient pasts. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press.

- Smith, Simon (1998). British Imperialism 1750–1970. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-3-12-580640-5. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- Taylor, Alan (2002). American Colonies: The Settling of North America. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0142002100.

- Taylor, Alan (2016). American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Turpin, Colin; Tomkins, Adam (2007). British government and the constitution (6th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-69029-4.

- Zolberg, Aristide R (2006). A nation by design: immigration policy in the fashioning of America. Russell Sage. ISBN 978-0-674-02218-8.

Further reading

- Berlin, Ira (1998). Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America. Belknap Press.

- Black, Conrad. Rise to Greatness: The History of Canada From the Vikings to the Present (2014), 1120pp excerpt

- Breen, T.H.; Hall, Timothy (2016). Colonial America in an Atlantic World (2nd ed.). Pearson.

- Burk, Kathleen (2008). Old World, New World: Great Britain and America from the Beginning. Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 978-0-87113-971-9.

- Carr, J. Revell (2008). Seeds of Discontent: The Deep Roots of the American Revolution, 1650-1750. Walker Books.

- Conrad, Margaret, Alvin Finkel and Donald Fyson. Canada: A History (Toronto: Pearson, 2012)

- Cooke, Jacob Ernest et al., ed. Encyclopedia of the North American Colonies. (3 vol. 1993)

- Dalziel, Nigel (2006). The Penguin Historical Atlas of the British Empire. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-101844-7. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- Elliott, John (2006). Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492-1830. Yale University Press.

- Games, Alison (2008). The Web of Empire: English Cosmopolitans in an Age of Expansion, 1560-1660. Oxford University Press.

- Gaskill, Malcolm (2014). Between Two Worlds: How the English Became Americans. Basic Books.

- Gipson, Lawrence. The British Empire Before the American Revolution (15 volumes, 1936–1970), Pulitzer Prize; highly detailed discussion of every British colony in the New World

- Horn, James (2005). A Land As God Made It: Jamestown and the Birth of America. Basic Books.

- Rose, J. Holland, A. P. Newton and E. A. Benians (gen. eds.), The Cambridge History of the British Empire, 9 vols. (1929–61); vol 1: "The Old Empire from the Beginnings to 1783" 934pp online edition Volume I

- Hyam, Ronald (2002). Britain's Imperial Century, 1815–1914: A Study of Empire and Expansion. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7134-3089-9.

- Lepore, Jill (1999). The Name of War: King Philip's War and the Origins of American Identity. Vintage.

- Louis, Wm. Roger (general editor), The Oxford History of the British Empire

- vol 1 The Origins of Empire ed. by Nicholas Canny

- vol 2 The Eighteenth Century ed. by P. J. Marshall excerpt and text search

- Mann, Charles C. (2011). 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created. Knopf.

- Marshall, P.J. (ed.) The Cambridge Illustrated History of the British Empire (1996). excerpt and text search

- Mawby, Spencer. Ordering Independence: The End of Empire in the Anglophone Caribbean, 1947-69 (Springer, 2012).

- McNaught, Kenneth. The Penguin History of Canada (Penguin books, 1988)

- Meinig, Donald William (1986). The Shaping of America: Atlantic America, 1492-1800. Yale University Press.

- Middleton, Richard; Lombard, Anne (2011). Colonial America: A History to 1763 (4th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Brendon, Piers (2007). The Decline and Fall of the British Empire, 1781–1997. Random House. ISBN 978-0-224-06222-0.

- Shorto, Russell (2004). The Island at the Center of the World: The Epic Story of Dutch Manhattan and the Forgotten Colony that Shaped America. Doubleday.

- Smith, Simon (1998). British Imperialism 1750–1970. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-3-12-580640-5.

- Sobecki, Sebastian. "New World Discovery". Oxford Handbooks Online (2015). DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935338.013.141

- Springhall, John (2001). Decolonization since 1945: the collapse of European overseas empires. Palgrave. ISBN 978-0-333-74600-4.

- Weidensaul, Scott (2012). The First Frontier: The Forgotten History of Struggle, Savagery, and Endurance in Early America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Historiography

- Canny, Nicholas. "Writing Atlantic History; or, Reconfiguring the History of Colonial British America." Journal of American History 86.3 (1999): 1093–1114. in JSTOR

- Hinderaker, Eric; Horn, Rebecca. "Territorial Crossings: Histories and Historiographies of the Early Americas," William and Mary Quarterly, (2010) 67#3 pp 395–432 in JSTOR

External links