History of Buddhism in India

Buddhism is an ancient Indian religion, which arose in and around the ancient Kingdom of Magadha (now in Bihar, India), and is based on the teachings of the Gautama Buddha[note 1] who was deemed a "Buddha" ("Awakened One"[4]). Buddhism spread outside of Magadha starting in the Buddha's lifetime.

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 8,442,972 (0.70%) in 2011[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Maharashtra · West Bengal · Madhya Pradesh · Uttar Pradesh · Chakma Autonomous District Council · Sikkim · Arunachal Pradesh · Ladakh · Tripura · Karnataka | |

| Languages | |

| Marathi • Hindi • Bengali • Sikkimese • Tibetan • Kannada | |

| Religion | |

| Buddhism (87% Navayana) |

With the reign of the Buddhist Mauryan Emperor Ashoka, the Buddhist community split into two branches: the Mahāsāṃghika and the Sthaviravāda, each of which spread throughout India and split into numerous sub-sects.[5] In modern times, two major branches of Buddhism exist: the Theravāda in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, and the Mahāyāna throughout the Himalayas and East Asia. The Buddhist tradition of Vajrayana is sometimes classified as a part of Mahāyāna Buddhism, but some scholars consider it to be a different branch altogether.[6]

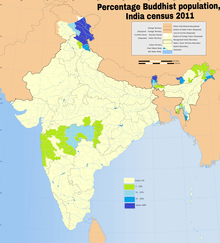

The practice of Buddhism as a distinct and organized religion lost influence after the Gupta reign (c.7th century CE), and declined from the land of its origin in around the 13th century, but not without leaving a significant impact on other local religious traditions. Except for the Himalayan region and south India, Buddhism almost became extinct in India after the arrival of Islam in the late 12th century. Buddhism is still practiced in the Himalayan areas such as Sikkim, Ladakh, Arunachal Pradesh, the Darjeeling hills in West Bengal, the Lahaul and Spiti areas of upper Himachal Pradesh, and Maharashtra. After B. R. Ambedkar's Dalit Buddhist movement, the number of Buddhists in India has increased considerably.[7] According to the 2011 census, Buddhists make up 0.7% of India's population, or 8.4 million individuals. Traditional Buddhists are less than 13% and Navayana Buddhists (Converted, Ambedkarite or Neo-Buddhists) comprise more than 87% of the Indian Buddhist community according to the 2011 Census of India.[8][9][10][11] According to the 2011 census, the largest concentration of Buddhism is in Maharashtra (6,530,000), where 77% of the total Buddhists in India reside. West Bengal (280,000), Madhya Pradesh (216,000), and Uttar Pradesh (200,000) are other states having large Buddhist populations. Ladakh (39.7%), Sikkim (27.4%), Arunachal Pradesh (11.8%), Mizoram (8.5%) and Maharashtra (5.8%) have emerged as top five states or union territories in terms of having the largest percentages of Buddhists.[1]

Background

Gautama Buddha

Buddha was born to a Kapilvastu head of the Shakya republic named Suddhodana. He employed sramana practices in a specific way, denouncing extreme asceticism and sole concentration-meditation, which were sramanic practices. Instead he propagated a Middle Way between the extremes of self-indulgence and self-mortification, in which self-restraint and compassion are central elements.

According to tradition, as recorded in the Pali Canon and the Agamas, Siddhārtha Gautama attained awakening sitting under a pipal tree, now known as the Bodhi tree in Bodh Gaya, India. Gautama referred to himself as the tathagata, the "thus-gone"; the developing tradition later regarded him to be as a Samyaksambuddha, a "Perfectly Self-Awakened One." According to tradition, he found patronage in the ruler of Magadha, emperor Bimbisāra. The emperor accepted Buddhism as personal faith and allowed the establishment of many Buddhist "Vihāras." This eventually led to the renaming of the entire region as Bihar.[12]

According to tradition, in the Deer Park in Sarnath near Vārāṇasī in northern India, Buddha set in motion the Wheel of Dharma by delivering his first sermon to the group of five companions with whom he had previously sought liberation. They, together with the Buddha, formed the first Saṅgha, the company of Buddhist monks, and hence, the first formation of Triple Gem (Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha) was completed.

For the remaining years of his life, the Buddha is said to have travelled in the Gangetic Plain of Northern India and other regions.

Buddha died in Kushinagar, Uttar Pradesh.[13][14]

Adherents

Followers of Buddhism, called Buddhists in English, referred to themselves as Saugata.[15] Other terms were Sakyans or Sakyabhiksu in ancient India.[16][17] Sakyaputto was another term used by Buddhists, as well as Ariyasavako[18] and Jinaputto.[19] Buddhist scholar Donald S. Lopez states they also used the term Bauddha.[20] The scholar Richard Cohen in his discussion about the 5th-century Ajanta Caves, states that Bauddha is not attested therein, and was used by outsiders to describe Buddhists, except for occasional use as an adjective.[21]

Early developments

Early Buddhist Councils

The Buddha did not appoint any successor, and asked his followers to work toward liberation following the instructions he had left. The teachings of the Buddha existed only in oral traditions. The Sangha held a number of Buddhist councils in order to reach consensus on matters of Buddhist doctrine and practice.

- Mahākāśyapa, a disciple of the Buddha, presided over the first Buddhist council held at Rājagṛha. Its purpose was to recite and agree on the Buddha's actual teachings and on monastic discipline. Some scholars consider this council fictitious.[22]

- The Second Buddhist Council is said to have taken place at Vaiśālī. Its purpose was to deal with questionable monastic practices like the use of money, the drinking of palm wine, and other irregularities; the council declared these practices unlawful.

- What is commonly called the Third Buddhist Council was held at Pāṭaliputra, and was allegedly called by Emperor Aśoka in the 3rd century BCE. Organized by the monk Moggaliputta Tissa, it was held in order to rid the sangha of the large number of monks who had joined the order because of its royal patronage. Most scholars now believe this council was exclusively Theravada, and that the dispatch of missionaries to various countries at about this time was nothing to do with it.

- What is often called the Fourth Buddhist council is generally believed to have been held under the patronage of Emperor Kaniṣka at Jālandhar in Kashmir, though the late Monseigneur Professor Lamotte considered it fictitious.[23] It is generally believed to have been a council of the Sarvastivāda school.

Early Buddhism Schools

The Early Buddhist Schools were the various schools in which pre-sectarian Buddhism split in the first few centuries after the passing away of the Buddha (in about the 5th century BCE). The earliest division was between the majority Mahāsāṃghika and the minority Sthaviravāda. Some existing Buddhist traditions follow the vinayas of early Buddhist schools.

- Theravāda: practised mainly in Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos and Bangladesh.

- Dharmaguptaka: followed in China, Korea, Vietnam, and Taiwan.

- Mūlasarvāstivāda: followed in Tibetan Buddhism.

The Dharmaguptakas made more efforts than any other sect to spread Buddhism outside India, to areas such as Afghanistan, Central Asia, and China, and they had great success in doing so.[24] Therefore, most countries which adopted Buddhism from China, also adopted the Dharmaguptaka vinaya and ordination lineage for bhikṣus and bhikṣuṇīs.

During the early period of Chinese Buddhism, the Indian Buddhist sects recognized as important, and whose texts were studied, were the Dharmaguptakas, Mahīśāsakas, Kāśyapīyas, Sarvāstivādins, and the Mahāsāṃghikas.[25] Complete vinayas preserved in the Chinese Buddhist canon include the Mahīśāsaka Vinaya (T. 1421), Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya (T. 1425), Dharmaguptaka Vinaya (T. 1428), Sarvāstivāda Vinaya (T. 1435), and the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya (T. 1442). Also preserved are a set of Āgamas (Sūtra Piṭaka), a complete Sarvāstivāda Abhidharma Piṭaka, and many other texts of the early Buddhist schools.

Early Buddhist schools in India often divided modes of Buddhist practice into several "vehicles" (yāna). For example, the Vaibhāṣika Sarvāstivādins are known to have employed the outlook of Buddhist practice as consisting of the Three Vehicles:[26]

Mahāyāna

Several scholars have suggested that the Prajñāpāramitā sūtras, which are among the earliest Mahāyāna sūtras,[27][28] developed among the Mahāsāṃghika along the Kṛṣṇa River in the Āndhra region of South India.[29]

The earliest Mahāyāna sūtras to include the very first versions of the Prajñāpāramitā genre, along with texts concerning Akṣobhya Buddha, which were probably written down in the 1st century BCE in the south of India.[30][31] Guang Xing states, "Several scholars have suggested that the Prajñāpāramitā probably developed among the Mahāsāṃghikas in southern India, in the Āndhra country, on the Kṛṣṇa River."[32] A.K. Warder believes that "the Mahāyāna originated in the south of India and almost certainly in the Āndhra country."[33]

Anthony Barber and Sree Padma note that "historians of Buddhist thought have been aware for quite some time that such pivotally important Mahayana Buddhist thinkers as Nāgārjuna, Dignaga, Candrakīrti, Āryadeva, and Bhavaviveka, among many others, formulated their theories while living in Buddhist communities in Āndhra."[34] They note that the ancient Buddhist sites in the lower Kṛṣṇa Valley, including Amaravati, Nāgārjunakoṇḍā and Jaggayyapeṭa "can be traced to at least the third century BCE, if not earlier."[35] Akira Hirakawa notes the "evidence suggests that many Early Mahayana scriptures originated in South India."[36]

Vajrayāna

Various classes of Vajrayana literature developed as a result of royal courts sponsoring both Buddhism and Saivism.[37] The Mañjusrimulakalpa, which later came to classified under Kriyatantra, states that mantras taught in the Shaiva, Garuda and Vaishnava tantras will be effective if applied by Buddhists since they were all taught originally by Manjushri.[38] The Guhyasiddhi of Padmavajra, a work associated with the Guhyasamaja tradition, prescribes acting as a Shaiva guru and initiating members into Saiva Siddhanta scriptures and mandalas.[39] The Samvara tantra texts adopted the pitha list from the Shaiva text Tantrasadbhava, introducing a copying error where a deity was mistaken for a place.[40]

Strengthening of Buddhism in India

The early spread of Buddhism

In the sixth and fifth centuries B.C.E., economic development made the merchant class increasingly important. Merchants were attracted to Buddhist teachings, which contrasted with existing Brahmin religious practice. The latter focussed on the social position of the Brahmin caste to the exclusion of the interests of other classes.[41] Buddhism became prominent in merchant communities and then spread throughout the Mauryan empire through commercial connections and along trade routes.[42] In this way, Buddhism also spread through the silk route into central Asia.[43]

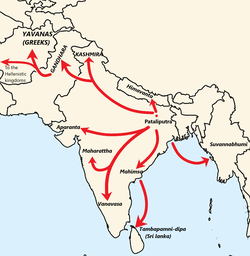

Aśoka and the Mauryan Empire

The Maurya empire reached its peak at the time of emperor Aśoka, who converted to Buddhism after the Battle of Kaliṅga. This heralded a long period of stability under the Buddhist emperor. The power of the empire was vast—ambassadors were sent to other countries to propagate Buddhism. Greek envoy Megasthenes describes the wealth of the Mauryan capital. Stupas, pillars and edicts on stone remain at Sanchi, Sarnath and Mathura, indicating the extent of the empire.

Emperor Aśoka the Great (304 BCE–232 BCE) was the ruler of the Maurya Empire from 273 BCE to 232 BCE.

Aśoka reigned over most of India after a series of military campaigns. Emperor Aśoka's kingdom stretched from South Asia and beyond, from present-day parts of Afghanistan in the north and Balochistan in the west, to Bengal and Assam in the east, and as far south as Mysore.

According to legend, emperor Aśoka was overwhelmed by guilt after the conquest of Kaliṅga, following which he accepted Buddhism as personal faith with the help of his Brahmin mentors Rādhāsvāmī and Mañjūśrī. Aśoka established monuments marking several significant sites in the life of Śakyamuni Buddha, and according to Buddhist tradition was closely involved in the preservation and transmission of Buddhism.[44]

In 2018, excavations in Lalitgiri in Odisha by archaeological survey of India revealed four monasteries along with ancient seals and inscriptions which show cultural continuity from post-Mauryan period to 13 century CE. In Ratnagiri and Konark in Odisha, Buddhist history as discovered in Lalitagiri is also shared. Museum has been made to preserve the ancient history and was inaugurated recently by Prime Minister Narendra Modi.[45]

Graeco-Bactrians, Sakas and Indo-Parthians

Menander was the most famous Bactrian king. He ruled from Taxila and later from Sagala (Sialkot). He rebuilt Taxila (Sirkap) and Puṣkalavatī. He became Buddhist and is remembered in Buddhists records due to his discussions with a great Buddhist philosopher in the book Milinda Pañha.

By 90 BC, Parthians took control of eastern Iran and around 50 BC put an end to last remnants of Greek rule in Afghanistan. By around 7 AD, an Indo-Parthian dynasty succeeded in taking control of Gandhāra. Parthians continued to support Greek artistic traditions in Gandhara. The start of the Gandhāran Greco-Buddhist art is dated to the period between 50 BC and 75 AD.

Kuṣāna Empire

The Kushan Empire under emperor Kaniṣka ruled the strongly Buddhist region of Gandhāra as well as other parts of northern India, Afghanistan and Pakistan. Kushan rulers were supporters of Buddhist institutions, and built numerous stupas and monasteries. During this period, Gandharan Buddhism spread through the trade routes protected by the Kushans, out through the Khyber pass into Central Asia. Gandharan Buddhist art styles also spread outward from Gandhāra to other parts of Asia.

The Pāla and Sena era

Under the rule of the Pāla and Sena kings, large mahāvihāras flourished in what is now Bihar and Bengal. According to Tibetan sources, five great Mahāvihāras stood out: Vikramashila, the premier university of the era; Nālanda, past its prime but still illustrious, Somapura, Odantapurā, and Jaggadala.[47] The five monasteries formed a network; "all of them were under state supervision" and there existed "a system of co-ordination among them . . it seems from the evidence that the different seats of Buddhist learning that functioned in eastern India under the Pāla were regarded together as forming a network, an interlinked group of institutions," and it was common for great scholars to move easily from position to position among them.[48]

According to Damien Keown, the kings of the Pala dynasty (8th to 12th century, Gangetic plains region) were a major supporter of Buddhism, various Buddhist and Hindu arts, and the flow of ideas between India, Tibet and China:[49][50]

During this period [Pala dynasty] Mahayana Buddhism reached its zenith of sophistication, while tantric Buddhism flourished throughout India and surrounding lands. This was also a key period for the consolidation of the epistemological-logical (pramana) school of Buddhist philosophy. Apart from the many foreign pilgrims who came to India at this time, especially from China and Tibet, there was a smaller but important flow of Indian pandits who made their way to Tibet...

— Damien Keown, [49]

Dharma masters

Bodhidharma lived during the 5th or 6th century and is traditionally credited as the transmitter of Chan Buddhism to China.

Bodhidharma lived during the 5th or 6th century and is traditionally credited as the transmitter of Chan Buddhism to China. Padmasambhava lived during the 8th-century and is credited for the construction of the first Buddhist monastery in Tibet at Samye.

Padmasambhava lived during the 8th-century and is credited for the construction of the first Buddhist monastery in Tibet at Samye.

Indian ascetics (Skt. śramaṇa) propagated Buddhism in various regions, including East Asia and Central Asia.

In the Edicts of Ashoka, Ashoka mentions the Hellenistic kings of the period as a recipient of his Buddhist proselytism.[51] The Mahavamsa describes emissaries of Ashoka, such as Dharmaraksita, as leading Greek ("Yona") Buddhist monks, active in Buddhist proselytism.[52]

Roman Historical accounts describe an embassy sent by the "Indian king Pandion (Pandya?), also named Porus," to Caesar Augustus around the 1st century. The embassy was travelling with a diplomatic letter in Greek, and one of its members was a sramana who burned himself alive in Athens, to demonstrate his faith. The event made a sensation and was described by Nicolaus of Damascus, who met the embassy at Antioch, and related by Strabo (XV,1,73)[53] and Dio Cassius (liv, 9). A tomb was made to the sramana, still visible in the time of Plutarch, which bore the mention:

- ("The sramana master from Barygaza in India")

Lokaksema is the earliest known Buddhist monk to have translated Mahayana Buddhist scriptures into the Chinese language. Gandharan monks Jnanagupta and Prajna contributed through several important translations of Sanskrit sutras into Chinese language.

The Indian dhyana master Buddhabhadra was the founding abbot and patriarch[54] of the Shaolin Temple. Buddhist monk and esoteric master from South India (6th century), Kanchipuram is regarded as the patriarch of the Ti-Lun school. Bodhidharma (c. 6th century) was the Buddhist Bhikkhu traditionally credited as the founder of Zen Buddhism in China.[55]

In 580, Indian monk Vinītaruci travelled to Vietnam. This, then, would be the first appearance of Vietnamese Zen, or Thien Buddhism.

Padmasambhava, in Sanskrit meaning "lotus-born", is said to have brought Tantric Buddhism to Tibet in the 8th century. In Bhutan and Tibet he is better known as "Guru Rinpoche" ("Precious Master") where followers of the Nyingma school regard him as the second Buddha. Śāntarakṣita, abbot of Nālanda and founder of the Yogacara-Madhyamaka is said to have helped Padmasambhava establish Buddhism in Tibet.

Indian monk Atiśa, holder of the mind training (Tib. lojong) teachings, is considered an indirect founder of the Geluk school of Tibetan Buddhism. Indian monks, such as Vajrabodhi, also travelled to Indonesia to propagate Buddhism.

Decline of Buddhism in India

The decline of Buddhism has been attributed to various factors. Regardless of the religious beliefs of their kings, states usually treated all the important sects relatively even-handedly.[56] This consisted of building monasteries and religious monuments, donating property such as the income of villages for the support of monks, and exempting donated property from taxation. Donations were most often made by private persons such as wealthy merchants and female relatives of the royal family, but there were periods when the state also gave its support and protection. In the case of Buddhism, this support was particularly important because of its high level of organization and the reliance of monks on donations from the laity. State patronage of Buddhism took the form of land grant foundations.[57]

Numerous copper plate inscriptions from India as well as Tibetan and Chinese texts suggest that the patronage of Buddhism and Buddhist monasteries in medieval India was interrupted in periods of war and political change, but broadly continued in Hindu kingdoms from the start of the common era through early 2nd millennium CE.[58][59][60] Modern scholarship and recent translations of Tibetan and Sanskrit Buddhist text archives, preserved in Tibetan monasteries, suggest that through much of 1st millennium CE in medieval India (and Tibet as well as other parts of China), Buddhist monks owned property and were actively involved in trade and other economic activity, after joining a Buddhist monastery.[61][62]

With the Gupta dynasty (~4th to 6th century), the growth in ritualistic Mahayana Buddhism, mutual influence between Hinduism and Buddhism,[63] the differences between Buddhism and Hinduism blurred, and Vaishnavism, Shaivism and other Hindu traditions became increasingly popular, and Brahmins developed a new relationship with the state.[64] As the system grew, Buddhist monasteries gradually lost control of land revenue. In parallel, the Gupta kings built Buddhist temples such as the one at Kushinagara,[65][66] and monastic universities such as those at Nalanda, as evidenced by records left by three Chinese visitors to India.[67][68][69]

According to Hazra, Buddhism declined in part because of the rise of the Brahmins and their influence in socio-political process.[70] According to Randall Collins, Richard Gombrich and other scholars, Buddhism's rise or decline is not linked to Brahmins or the caste system, since Buddhism was "not a reaction to the caste system", but aimed at the salvation of those who joined its monastic order.[71][72][73]

The 11th century Persian traveller Al-Biruni writes that there was 'cordial hatred' between the Brahmins and Sramana Buddhists.[74] Buddhism was also weakened by rival Hindu philosophies such as Advaita Vedanta, growth in temples and an innovation of the bhakti movement. Advaita Vedanta proponent Adi Shankara is believed to have "defeated Buddhism", although he never debated with any Buddhist scholar, and established Vedanta as supreme philosophy. This rivalry undercut Buddhist patronage and popular support.[75] The period between 400 CE and 1000 CE thus saw gains by the Vedanta school of Hinduism over Buddhism[76] and Buddhism had vanished from Afghanistan and north India by early 11th century. India was now Brahmanic, not Buddhistic; Al-Biruni could never find a Buddhistic book or a Buddhist person in India from whom he could learn.[77]

According to some scholars such as Lars Fogelin, the decline of Buddhism may be related to economic reasons, wherein the Buddhist monasteries with large land grants focussed on non-material pursuits, self-isolation of the monasteries, loss in internal discipline in the sangha, and a failure to efficiently operate the land they owned.[60][78]

The Hun invasions

Chinese scholars travelling through the region between the 5th and 8th centuries, such as Faxian, Xuanzang, I-ching, Hui-sheng, and Sung-Yun, began to speak of a decline of the Buddhist Sangha, especially in the wake of the Hun invasion from central Asia.[79] Xuanzang, the most famous of Chinese travellers, found “millions of monasteries” in north-western India reduced to ruins by the Huns.[79][80]

Muslim conquerors

The Muslim conquest of the Indian subcontinent was the first great iconoclastic invasion into South Asia.[81] By the end of twelfth century, Buddhism had mostly disappeared,[79][82] with the destruction of monasteries and stupas in medieval northwest and western India (now Pakistan and north India).[83]

In the north-western parts of medieval India, the Himalayan regions, as well regions bordering central Asia, Buddhism once facilitated trade relations, states Lars Fogelin. With the Islamic invasion and expansion, and central Asians adopting Islam, the trade route-derived financial support sources and the economic foundations of Buddhist monasteries declined, on which the survival and growth of Buddhism was based.[78][84] The arrival of Islam removed the royal patronage to the monastic tradition of Buddhism, and the replacement of Buddhists in long-distance trade by the Muslims eroded the related sources of patronage.[83][84]

In the Gangetic plains, Orissa, northeast and the southern regions of India, Buddhism survived through the early centuries of the 2nd millennium CE.[78] The Islamic invasion plundered wealth and destroyed Buddhist images,[85] and consequent take over of land holdings of Buddhist monasteries removed one source of necessary support for the Buddhists, while the economic upheaval and new taxes on laity sapped the laity support of Buddhist monks.[78]

Monasteries and institutions such as Nalanda were abandoned by Buddhist monks around 1200 CE, who flee to escape the invading Muslim army, after which the site decayed over the Islamic rule in India that followed.[87][88]

The last empire to support Buddhism, the Pala dynasty, fell in the 12th century, and Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khalji, a general of the early Delhi Sultanate, destroyed monasteries and monuments and spread Islam in Bengal.[79] According to Randall Collins, Buddhism was already declining in India before the 12th century, but with the pillage by Muslim invaders it nearly became extinct in India in the 1200s.[89] In the 13th century, states Craig Lockard, Buddhist monks in India escaped to Tibet to escape Islamic persecution;[90] while the monks in western India, states Peter Harvey, escaped persecution by moving to south Indian Hindu kingdoms that were able to resist the Muslim power.[91]

Surviving Buddhists

Many Indian Buddhists fled south. It is known that Buddhists continued to exist in India even after the 14th century from texts such as the Chaitanya Charitamrita. This text outlines an episode in the life of Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (1486–1533), a Vaisnava saint, who was said to have entered into a debate with Buddhists in Tamil Nadu.[92]

The Tibetan Taranatha (1575–1634) wrote a history of Indian Buddhism, which mentions Buddhism as having survived in some pockets of India during his time.[93] He mentions the Buddhist sangh as having survived in Konkana, Kalinga, Mewad, Chittor, Abu, Saurastra, Vindhya mountains, Ratnagiri, Karnataka etc. A Jain author Gunakirti (1450-1470) wrote a Marathi text, Dhamramrita,[94] where he gives the names of 16 Buddhist orders. Dr. Johrapurkar noted that among them, the names Sataghare, Dongare, Navaghare, Kavishvar, Vasanik and Ichchhabhojanik still survive in Maharashtra as family names.[95]

Buddhism also survived to the modern era in the Himalayan regions such as Ladakh, with close ties to Tibet.[96] A unique tradition survives in Nepal's Newar Buddhism.

Abul Fazl, the courtier of Mughal emperor Akbar, states, "For a long time past scarce any trace of them (the Buddhists) has existed in Hindustan." When he visited Kashmir in 1597, he met with a few old men professing Buddhism, however he 'saw none among the learned'. This is can also be seen from the fact that Buddhist priests were not present amidst learned divines that came to the Ibadat Khana of Akbar at Fatehpur Sikri.[97]

.jpg) Tawang Monastery in Arunachal Pradesh, was built in the 1600s, is the largest monastery in India and second largest in the world after the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet.

Tawang Monastery in Arunachal Pradesh, was built in the 1600s, is the largest monastery in India and second largest in the world after the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet. Rumtek Monastery in Sikkim was built under the direction of Changchub Dorje, 12th Karmapa Lama in the mid-1700s.[98]

Rumtek Monastery in Sikkim was built under the direction of Changchub Dorje, 12th Karmapa Lama in the mid-1700s.[98]

Causes within the Buddhist tradition of the time

Some scholars suggest that a part of the decline of Buddhist monasteries was because it was detached from everyday life in India and did not participate in the ritual social aspects such as the rites of passage (marriage, funeral, birth of child) like other religions.[83]

Revival of Buddhism in India

Maha Bodhi Society

The modern revival of Buddhism in India began in the late nineteenth century, led by Buddhist modernist institutions such as the Maha Bodhi Society (1891), the Bengal Buddhist Association (1892) and the Young Men's Buddhist Association (1898). These institutions were influenced by modernist South Asian Buddhist currents such as Sri Lankan Buddhist modernism as well as Western Oriental scholarship and spiritual movements like Theosophy.[99] A central figure of this movement was Sri Lankan Buddhist leader Anagarika Dharmapala, who founded the Maha Bodhi Society in 1891.[100] An important focus of the Maha Bodhi Society's activities in India became the recovery, conservation and restoration of important Buddhist sites, such as Bodh Gaya and its Mahabodhi temple.[99] Dharmapāla and the society promoted the building of Buddhist vihāras and temples in India, including the one at Sarnath, the place of Buddha's first sermon. He died in 1933, the same year he was ordained a bhikkhu.[100]

Following Indian independence, India's ancient Buddhist heritage became an important element for nation building, and prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru looked to the Mauryan empire for symbols of pan-Indian unity which were neither Hindu nor Muslim, such as the Dhammachakra.[101] Indian Buddhist sites also received Indian government support in preparation for the 2,500th Buddha Jayanti held in 1956, as well as providing rent free land in several pilgrimage centers for Asian Buddhist groups to build temples and rest houses.[102]

Important Indian Buddhist intellectuals of the modern period include Rahul Sankrityayan (1893-1963), Dharmanand Kosambi (1876-1941) and Bhadant Anand Kausalyayan.[103] The Bengal Buddhist Kripasaran Mahasthavir (1865-1926) founded the Bengal Buddhist Association in 1892. In Tamil Nadu, the Tamil Iyothee Thass (1845-1914) was a major figure who promoted Buddhism and called the Paraiyars to convert.[104]

The Indian government and the states have continued to promote the development of Buddhist pilgrimage sites ("the Buddhist Circuit"), both as a source of tourism and as a promotion of India's Buddhist heritage which is an important cultural resource for India's foreign diplomatic ties.[105] Another recent development is the establishment of the new Nalanda University in Bihar (2010).[106]

Dalit Buddhist movement

In the 1950s, the Dalit political leader B. R. Ambedkar (1891-1956) influenced by his reading of Pali sources and Indian Buddhists like Dharmanand Kosambi and Lakshmi Narasu, began promoting conversion to Buddhism for Indian low caste Dalits.[102] His Dalit Buddhist Movement was most successful in the Indian states of Maharashtra, which saw large scale conversions.[102] Ambedkar's "Neo Buddhism" included a strong element of social and political protest against Hinduism and the Indian caste system.[108] His magnum opus, The Buddha and His Dhamma, incorporated Marxist ideas of class struggle into Buddhist views of dukkha and argued that Buddhist morality could be used to "reconstruct society and to build up a modern, progressive society of justice, equality, and freedom".[108]

The conversion movement has generally been limited to certain social demographics, such as the Mahar caste of Maharashtra and the Jatavs.[108] Although they have renounced Hinduism in practice, a community survey showed adherence to many practices of the old faith including endogamy, worshipping the traditional family deity etc.[109]

Major organizations of this movement are the Buddhist Society of India (the Bharatiya Bauddha Mahasabha) and the Triratna Buddhist Community (the Triratna Bauddha Mahasangha).[110]

Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism has also grown in India during the modern era, mainly due to the growth of the Tibetan Diaspora. The arrival of the 14th Dalai Lama with over 85,000 Tibetan refugees 1959 had a significant impact on the revival of Buddhism in India.[111] Large numbers of Tibetans settled in Dharamsala, Himachal Pradesh, which became the headquarters of the Tibetan Government in Exile. Another large Tibetan refugee settlement is in Bylakuppe, Karnataka. Tibetan refugees also contributed to the revitalization of the Buddhist traditions in Himalayan regions such as Lahaul and Spiti district, Ladakh, Tawang and Bomdila.[111] Tibetan Buddhists have also contributed to the building of temples and institutions in the Buddhist sites and ruins of India.[112]

The Dalai Lama's brother, Gyalo Thondup, himself lives in Kalimpong and his wife established the Tibetan Refugee Centre in Darjeeling . The 17th Karmapa also arrived in India in 2000 and continues education and has taken traditional role to head Karma Kagyu sect of Tibetan Buddhism and every year leads the Kagyu Monlam in Bodh Gaya attended by thousands of monks and followers. Palpung Sherabling monastery seat of the 12th Tai Situpa located in Kangra, Himachal Pradesh is the largest Kagyu monastery in India and has become an important centre of Tibetan Buddhism. Penor Rinpoche, the head of Nyingma, the ancient school of Tibetan Buddhism re-established a Nyingma monastery in Bylakuppe, Mysore. This is the largest Nyingma monastery today. Monks from Himalayan regions of India, Nepal, Bhutan and from Tibet join this monastery for their higher education. Penor Rinpoche also founded Thubten Lekshey Ling, a dharma center for lay practitioners in Bangalore. Vajrayana Buddhism and Dzogchen (maha-sandhi) meditation again became accessible to aspirants in India after that.

Vipassana movement

The Vipassana movement is a modern tradition of Buddhist meditation practice. In India, the most influential Vipassana organization is the Vipassana Research Institute founded by S.N. Goenka (1924-2013) who promoted Buddhist Vipassana meditation in a modern and non-sectarian manner.[113] Goenka's network of meditation centers who offered 10 day retreats. Many institutions—both government and private sector—now offer courses for their employees.[114] This form is mainly practiced by elite and middle class Indians. This movement has spread to many other countries in Europe, America and Asia. In November 2008, the construction of the Global Vipassana Pagoda was completed on the outskirts of Mumbai.

Culture

Communities

- Marathi Buddhists (including Mahar) is the most populous Buddhist community in India. is Various indigenous ethnic Buddhist communities such as the Sherpas, Bhutias, Lepchas, Tamangs, Yolmos, and ethnic Tibetans can be found in the Darjeeling Himalayan hill region.

- Beda people : The Beda people are an Buddhist community of the Indian union territory of Ladakh, where they practise their traditional occupation of musicianship.

- Bengali Buddhists: Bengali Buddhist people mainly live in Bangladesh (500,000), and Indian states West Bengal (282,898) and Tripura (125,182). Bengali Buddhists are followers of Therevada Buddhism.[115]

- Bhotiya

- Bhutia

- Bodh people

- Bugun

- Chakma people

- Chugpa tribe

- Gurung people

- Khamba people

- Khamti people

- Khamyang people

- Lepcha people

- Lishipa tribe

- Mahar

- Marathi Buddhists

- Na people

- Rakhine people

- Sherpa people

- Tai Phake people

- Tamang people

Festivals

Indian Buddhists celebrate many festivals. Ambedkar Jayanti, Dhammachakra Pravartan Day and Buddha's Birthday are three major festivals of Navayana Buddhists. Traditional Buddhists celebrate Losar, Buddha Purnima and other festivals.

- Ambedkar Jayanti (Ambedkar's birthday) : Ambedkar Jayanti is a major Buddhist festival in India. The annual festival observed on 14 April to commemorate the memory of B. R. Ambedkar. Ambedkar was a Buddhist spiritual leader and he revivaled Buddhism in India.[116][117] Ambedkar Jayanti is celebrated not just in India rather all around the world.[118] Ambedkar Jayanti processions are carried out by his Buddhist followers at Chaitya Bhoomi in Mumbai and Deeksha Bhoomi in Nagpur. Large numbers of Indian Buddhist people visit viharas and local statues commemorating Ambedkar in procession with lot of fanfare.[119]

_and_14_October.jpg)

- Dhammachakra Pravartan Day is a day to celebrate the Buddhist conversion of Ambedkar and approximately 600,000 followers on 14 October 1956 at Deekshabhoomi.[120] Every year on Ashoka Vijayadashami, millions of Buddhists gather at Deekshabhoomi to celebrate the mass conversion. Many Buddhist also visit there local Buddhist sites to celebrate the festival. Every year on the day, thousand of people embrace Buddhism.[121]

Branches

According to an IndiaSpend analysis of 2011 Census data, there are more than 8.4 million Buddhists in India and 87% of them are neo-Buddhists or Navayana Buddhists. They are converted from other religions, mostly Dalits (Scheduled Caste) who changed religion to escape Hindu caste oppression. The remaining 13% of Buddhists belong to traditional communities (Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana) of the northeast and northern Himalayan regions.[8][11]

Demographics

| Year | Percent | Increase |

|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 0.05% | - |

| 1961 | 0.74% | +0.69% |

| 1971 | 0.70% | -0.04% |

| 1981 | 0.71% | +0.01% |

| 1991 | 0.76% | +0.05% |

| 2001 | 0.77% | +0.01% |

| 2011 | 0.70% | -0.07% |

The Buddhist percentage has decreased from 0.74% in 1961 to 0.70% in 2011.[122] Between 2001 and 2011, Buddhist population declined in Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka, Delhi, and Punjab.[123]

According to the 2011 Census of India there are 8.4 million Buddhists in India. Maharashtra has the highest number of Buddhists in India, with 5.81% of the total population.[1][124] Almost 90 per cent of Navayana or Neo-Buddhists live in the state. Marathi Buddhists, who live in Maharashtra, are the largest Buddhist community in India. Most Buddhist Marathi people belong to the former Mahar community.[125][126]

| Buddhist population growth | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Population | %± | |

| 1951 | 180,823 | — | |

| 1961 | 3,250,227 | 1,697.5% | |

| 1971 | 3,812,325 | 17.3% | |

| 1981 | 4,720,000 | 23.8% | |

| 1991 | 6,388,000 | 35.3% | |

| 2001 | 7,955,207 | 24.5% | |

| 2011 | 8,442,972 | 6.1% | |

| Source: Census of India | |||

In the 1951 census of India, 181,000 (0.05%) respondents said they were Buddhist.[127] The 1961 census, taken after B. R. Ambedkar adopted Navayana Buddhism with his millions of followers in 1956, showed an increased to 3.25 million (0.74%). Buddhism is growing rapidly in the Scheduled Caste (dalit) community. According to the 2011 census, Scheduled Castes Buddhists grew by 38 percent in the country. According to the 2011 census, 5.76 million (69%) Indian Buddhists belong to the Scheduled Caste.[128]

Census of India, 2011

| State and union territory | Buddhist Population (approximate) | Buddhist Population (%) | % of total Buddhists |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maharashtra | 6,531,200 | 5.81% | 77.36% |

| West Bengal | 282,898 | 0.31% | 3.35% |

| Madhya Pradesh | 216,052 | 0.30% | 2.56% |

| Uttar Pradesh | 206,285 | 0.10% | 2.44% |

| Sikkim | 167,216 | 27.39% | 1.98% |

| Arunachal Pradesh | 162,815 | 11.77% | 1.93% |

| Tripura | 125,385 | 3.41% | 1.49% |

| Jammu and Kashmir (before 2019 formation of Ladakh) | 112,584 | 0.90% | 1.33% |

| Ladakh (formed 2019) | 108,761 | 39.65% | 1.29% |

See also

Notes

- Born as a prince of the ancient Kapilavastu kingdom in ancient India, now in Lumbini of Nepal.[3]

References

- "Buddhist Religion in India - Statewise Census 2011". www.census2011.co.in.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "Mahabodhi Temple Complex at Bodh Gaya". Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- Smith, Vincent A. (1914). The Early History of India from 600 B.C. to the Muhammadan Conquest Including the Invasion of Alexander the Great (3rd ed.). London: Oxford University Press. pp. 168–169.

- Monier-Williams, Monier. Dictionary of Sanskrit. OUP.

- Akira Hirakawa, Paul Groner, A history of Indian Buddhism: from Śākyamuni to early Mahāyāna. Reprint published by Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1993, page 2.

- "Buddhism: Description of the Vajrayāna tradition". Religious Tolerance. Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance. 25 April 2010. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- "Ambedkar and Buddhism". Motilal Banarsidass Publishe. 10 November 2006 – via Google Books.

- "Dalits who converted to Buddhism better off in literacy and well-being: Survey". 2 July 2017.

- Peter Harvey, An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices, p. 400. Cambridge University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-052185-942-4

- The New York Times guide to essential knowledge: a desk reference for the curious mind. Macmillan 2004, page 513.

- "Dalits Are Still Converting to Buddhism, but at a Dwindling Rate". The Quint. 17 June 2017.

- India by Stanley Wolpert (Page 32)

- United Nations (2003). Promotion of Buddhist Tourism Circuits in Selected Asian Countries. United Nations Publications. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-92-1-120386-8.

- Kevin Trainor (2004). Buddhism: The Illustrated Guide. Oxford University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-19-517398-7.

- P. 178 The Vision of Dhamma: Buddhist Writings of Nyanaponika Thera By Nyanaponika (Thera), Erich Fromm

- Beyond Enlightenment: Buddhism, Religion, Modernity by Richard Cohen. Routledge 1999. ISBN 0-415-54444-0. pg 33. "Donors adopted Sakyamuni Buddha’s family name to assert their legitimacy as his heirs, both institutionally and ideologically. To take the name of Sakya was to define oneself by one’s affiliation with the Buddha, somewhat like calling oneself a Buddhist today.

- Sakya or Buddhist Origins by Caroline Rhys Davids (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner, 1931) pg 1. "Put away the word “Buddhism” and think of your subject as “Sakya.” This will at once place you for your perspective at a true point . . You are now concerned to learn less about 'Buddha' and 'Buddhism,' and more about him whom India has ever known as Sakya-muni, and about his men who, as their records admit, were spoken of as the Sakya-sons, or men of the Sakyas."

- P. 56 A Dictionary of the Pali Language By Robert Cæsar Childers

- P. 171 A Dictionary of the Pali Language By Robert Cæsar Childers

- Curators of the Buddha By Donald S. Lopez. University of Chicago Press. pg 7

- Beyond Enlightenment: Buddhism, Religion, Modernity by Richard Cohen. Routledge 1999. ISBN 0-415-54444-0. pg 33. Quote: [Bauddha is] "a secondary derivative of Buddha, in which the vowel’s lengthening indicates connection or relation. Things that are bauddha pertain to the Buddha, just as things-saiva relate to Shiva and things-Vaisnava belong to Vishnu. (...) bauddha can be both adjectival and nominal; it can be used for doctrines spoken by the Buddha, objects enjoyed by him, texts attributed to him, as well as individuals, communities, and societies that offer him reverence or accept ideologies certified through his name. Strictly speaking, Sakya is preferable to bauddha since the latter is not attested at Ajanta. In fact, as a collective noun, bauddha is an outsider’s term. The bauddha did not call themselves this in India, though they did sometimes use the word adjectivally (e.g., as a possessive, the Buddha’s)."

- Williams, Mahayana Buddhism, Routledge, 1989, page 6

- the Teaching of Vimalakīrti, Pali Text Society, page XCIII

- Warder, A.K. Indian Buddhism. 2000. p. 278

- Warder, A.K. Indian Buddhism. 2000. p. 281

- Nakamura, Hajime. Indian Buddhism: A Survey With Bibliographical Notes. 1999. p. 189

- Williams, Paul. Buddhist Thought. Routledge, 2000, pages 131.

- Williams, Paul. Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations 2nd edition. Routledge, 2009, pg. 47.

- Guang Xing. The Concept of the Buddha: Its Evolution from Early Buddhism to the Trikaya Theory. 2004. pp. 65–66 "Several scholars have suggested that the Prajñāpāramitā probably developed among the Mahasamghikas in Southern India, in the Andhra country, on the Krsna River."

- Akira, Hirakawa (translated and edited by Paul Groner) (1993). A History of Indian Buddhism. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass: pp. 253, 263, 268

- "The south (of India) was then vigorously creative in producing Mahayana Sutras" – Warder, A.K. (3rd edn. 1999). Indian Buddhism: p. 335.

- Guang Xing. The Concept of the Buddha: Its Evolution from Early Buddhism to the Trikaya Theory. 2004. pp. 65–66

- Warder, A.K. Indian Buddhism. 2000. p. 313

- Padma, Sree. Barber, Anthony W. Buddhism in the Krishna River Valley of Andhra. SUNY Press 2008, pg. 1.

- Padma, Sree. Barber, Anthony W. Buddhism in the Krishna River Valley of Andhra. SUNY Press 2008, pg. 2.

- Akira, Hirakawa (translated and edited by Paul Groner) (1993. A History of Indian Buddhism. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass: p. 252, 253

- Sanderson, Alexis. "The Śaiva Age: The Rise and Dominance of Śaivism during the Early Medieval Period." In: Genesis and Development of Tantrism, edited by Shingo Einoo. Tokyo: Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo, 2009. Institute of Oriental Culture Special Series, 23, pp. 124.

- Sanderson, Alexis. "The Śaiva Age: The Rise and Dominance of Śaivism during the Early Medieval Period." In: Genesis and Development of Tantrism, edited by Shingo Einoo. Tokyo: Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo, 2009. Institute of Oriental Culture Special Series, 23, pp. 129-131.

- Sanderson, Alexis. "The Śaiva Age: The Rise and Dominance of Śaivism during the Early Medieval Period." In: Genesis and Development of Tantrism, edited by Shingo Einoo. Tokyo: Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo, 2009. Institute of Oriental Culture Special Series, 23, pp. 144-145.

- Huber, Toni (2008). The holy land reborn : pilgrimage & the Tibetan reinvention of Buddhist India. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 94–95. ISBN 978-0-226-35648-8.

- "During the sixth and fifth centuries B.C.E. (Before Common Era), commerce and cash became increasingly important in an economy previously dominated by self-sufficient production and bartered exchange. Merchants found Buddhist moral and ethical teachings an attractive alternative to the esoteric rituals of the traditional Brahmin priesthood, which seemed to cater exclusively to Brahmin interests while ignoring those of the new and emerging social classes." Jerry Bentley, Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 43.

- "Furthermore, Buddhism was prominent in communities of merchants, who found it well suited to their needs and who increasingly established commercial links throughout the Mauryan empire. Jerry Bentley, Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 46.

- "Merchants proved to be an efficient vector of the Buddhist faith, as they established diaspora communities in the string of oasis towns-Merv, Bukhara, Samarkand, Kashgar, Khotan, Kuqa, Turpan, Dunhuang - that served as lifeline of the silk roads through central Asia." Jerry Bentley, Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 47-48.

- "Fa-hsien: A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms: Chapter XXVII: Patalipttra or Patna, in Magadha. King Aśoka's Spirit Built Palace and Halls. The Buddhist Brahman, Radha-Sami. Dispensaries and Hospitals". Archived from the original on 17 July 2005.

- Singh, Shiv Sahay (23 December 2018). "PM to open Buddhist site museum at Lalitgiri in Odisha" – via www.thehindu.com.

- John M. Rosenfield (1967). The Dynastic Arts of the Kushans. University of California Press. pp. xxiii, 74–76, 82, 94–95.

- Vajrayoginī: Her Visualization, Rituals, and Forms by Elizabeth English. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-329-X pg 15

- Buddhist Monks And Monasteries Of India: Their History And Contribution To Indian Culture. by Dutt, Sukumar. George Allen and Unwin Ltd, London 1962. pg 352-3

- Damien Keown (2004). A Dictionary of Buddhism. Oxford University Press. pp. 208–209. ISBN 978-0-19-157917-2.

- Heather Elgood (2000). Hinduism and the Religious Arts. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-8264-9865-6.

- "The conquest by Dharma has been won here, on the borders, and even six hundred yojanas (5,400-9,600 km) away, where the Greek king Antiochos rules, beyond there where the four kings named Ptolemy, Antigonos, Magas and Alexander rule, likewise in the south among the Cholas, the Pāṇḍyas, and as far as Tāmraparṇi." (Edicts of Ashoka, 13th Rock Edict, S. Dhammika)

- Geiger, Wilhelm; Bode, Mabel Haynes, trans.; Frowde, H. (ed.) (1912). The Mahavamsa or, the great chronicle of Ceylon, London: Pali Text Society, Oxford University Press; chapter XII

- "Strabo, Geography, NOTICE". Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- Faure, Bernard. Chan Insights and Oversights: an epistemological critique of the Chan tradition, Princeton University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-691-02902-4

- "Concise Encyclopædia Britannica Article on Bodhidharma". Archived from the original on 5 September 2007.

- Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press, 2000, page 182.

- Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press, 2000, pages 180, 182.

- Hajime Nakamura (1980). Indian Buddhism: A Survey with Bibliographical Notes. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 145–148 with footnotes. ISBN 978-81-208-0272-8.

- Akira Shimada (2012). Early Buddhist Architecture in Context: The Great Stūpa at Amarāvatī (ca. 300 BCE-300 CE). BRILL Academic. pp. 200–204. ISBN 978-90-04-23326-3.

- Gregory Schopen (1997). Bones, Stones, and Buddhist Monks: Collected Papers on the Archaeology, Epigraphy, and Texts of Monastic Buddhism in India. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 259–278. ISBN 978-0-8248-1870-8.

- Gregory Schopen (2004). Buddhist Monks and Business Matters: Still More Papers on Monastic Buddhism in India. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-0-8248-2774-8.

- Huaiyu Chen (2007). The Revival of Buddhist Monasticism in Medieval China. Peter Lang. pp. 132–149. ISBN 978-0-8204-8624-6.

- History and life: the world and its people, Patricia Gutierrez, T. Walter Wallbank, p. 67-69, In time, Indian Buddhism became so much like Hinduism that it was looked upon as a sect of Hinduism. This ans. i caused a steady decline.

- Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press, 2000, page 207-211.

- Gina Barns (1995). "An Introduction to Buddhist Archaeology". World Archaeology. 27 (2): 166–168. doi:10.1080/00438243.1995.9980301.

- Robert Stoddard (2010). "The Geography of Buddhist Pilgrimage in Asia". Pilgrimage and Buddhist Art. Yale University Press. 178: 3–4.

- Hartmut Scharfe (2002). Handbook of Oriental Studies. BRILL Academic. pp. 144–153. ISBN 90-04-12556-6.

- Craig Lockard (2007). Societies, Networks, and Transitions: Volume I: A Global History. Houghton Mifflin. p. 188. ISBN 978-0618386123.

- Charles Higham (2014). Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilizations. Infobase. pp. 121, 236. ISBN 978-1-4381-0996-1.

- Kanai Lal Hazra (1995). The Rise And Decline Of Buddhism In India. Munshiram Manoharlal. pp. 371–385. ISBN 978-81-215-0651-9.

- Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press, 2000, page 205-206

- Christopher S. Queen; Sallie B. King (1996). Engaged Buddhism: Buddhist Liberation Movements in Asia. State University of New York Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-7914-2844-3.

- Richard Gombrich (2012). Buddhist Precept & Practice. Routledge. pp. 344–345. ISBN 978-1-136-15623-6.

- Muhammad ibn Ahmad Biruni; Edward C. Sachau (Translator) (1910). Alberuni's India: An Account of the Religion, Philosophy, Literature, Geography, Chronology, Astronomy, Customs, Laws and Astrology of India about AD 1030. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd., London. p. 21.

- Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press, 2000, pages=189, 190.

- "BBC - Religions - Hinduism: History of Hinduism". Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- Muhammad ibn Ahmad Biruni; Edward C. Sachau (Translator) (1910). Alberuni's India: An Account of the Religion, Philosophy, Literature, Geography, Chronology, Astronomy, Customs, Laws and Astrology of India about AD 1030. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd., London. pp. xlv, xlvii, 249.

- Lars Fogelin (2015). An Archaeological History of Indian Buddhism. Oxford University Press. pp. 229–230. ISBN 978-0-19-994823-9.

- Wendy Doniger (1999). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions. Merriam-Webster. pp. 155–157. ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "Historical Development of Buddhism in India - Buddhism under the Guptas and Palas". Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- Levy, Robert I. Mesocosm: Hinduism and the Organization of a Traditional Newar City in Nepal. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1990 1990.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "Historical Development of Buddhism in India - Buddhism under the Guptas and Palas". Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- McLeod, John, "The History of India", Greenwood Press (2002), ISBN 0-313-31459-4, pg. 41-42.

- André Wink (1997). Al-Hind the Making of the Indo-Islamic World. BRILL Academic. pp. 348–349. ISBN 90-04-10236-1.

- Peter Harvey (2013). An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices. Cambridge University Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-521-85942-4., Quote: "From 986 CE, the Muslim Turks started raiding northwest India from Afghanistan, plundering western India early in the eleventh century. Force conversions to Islam were made, and Buddhist images smashed, due to the Islamic dislike of idolarty. Indeed in India, the Islamic term for an 'idol' became 'budd'."

- The Maha-Bodhi By Maha Bodhi Society, Calcutta (page 8)

- Richard H. Robinson; Sandra Ann Wawrytko; Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu (1996). The Buddhist Religion: A Historical Introduction. Thomson. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-534-20718-2.

- Mark Juergensmeyer; Wade Clark Roof (2011). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. SAGE Publications. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-4522-6656-5.

- Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press, 2000, pages 184-185

- Craig Lockard (2007). Societies, Networks, and Transitions: Volume I: A Global History. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 364. ISBN 0-618-38612-2.

- Peter Harvey (2013). An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices. Cambridge University Press. pp. 194–195. ISBN 978-0-521-85942-4.

- Amore, Roy C; Developments in Buddhist Thought: Canadian Contributions to Buddhist Studies, page 72

- Tharanatha; Chattopadhyaya, Chimpa, Alaka, trans. (2000). History of Buddhism in India, Motilal Books UK, ISBN 8120806964.

- Datta, Amaresh (10 November 1988). "Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: Devraj to Jyoti". Sahitya Akademi – via Google Books.

- Shodha Tippana, Pro. Vidyadhar Joharapurkar, in Anekanta, June 1963, pp. 73-75.

- Warder, AK; Indian Buddhism, page 486

- Ramesh Chandra Majumdar (1951). The History and Culture of the Indian People: The struggle for empire. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. p. 426.

- Achary Tsultsem Gyatso; Mullard, Saul & Tsewang Paljor (Transl.): A Short Biography of Four Tibetan Lamas and Their Activities in Sikkim, in: Bulletin of Tibetology Nr. 49, 2/2005, p. 57.

- Jerryson, Michael K. (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Buddhism, p. 41.

- Ahir, D.C. (1991). Buddhism in Modern India. Satguru. ISBN 81-7030-254-4.

- Jerryson, Michael K. (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Buddhism, p. 42.

- Jerryson, Michael K. (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Buddhism, p. 47.

- Jerryson, Michael K. (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Buddhism, p. 42, 50

- Bergunder, Michael (2004). "Contested Past: Anti-Brahmanical and Hindu nationalist reconstructions of Indian prehistory" (PDF). Historiographia Linguistica. 31 (1): 59–104.

- Jerryson, Michael K. (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Buddhism, p. 54.

- Jerryson, Michael K. (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Buddhism, p. 55.

- Bhagwat, Ramu (19 December 2001). "Ambedkar memorial set up at Deekshabhoomi". Times of India. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- Jerryson, Michael K. (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Buddhism, p. 48.

- Shastree, Uttara (1996). Religious converts in India : socio-political study of neo-Buddhists (1. ed.). New Delhi: Mittal Publ. pp. 67–82. ISBN 8170996295. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- Jerryson, Michael K. (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Buddhism, p. 49

- Jerryson, Michael K. (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Buddhism, p. 51.

- Jerryson, Michael K. (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Buddhism, p. 52.

- "Vipassana pioneer SN Goenka is dead". Zeenews.india.com. 30 September 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- "BBC NEWS - South Asia - India's youth hit the web to worship". Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- Bechert, Heinz (1970). "Theravada Buddhist Sangha: Some General Observations on Historical and Political Factors in its Development". The Journal of Asian Studies. 29 (4): 761–778. doi:10.2307/2943086. JSTOR 2943086.

- "Declaration of Holiday on 14th April, 2015 – Birthday of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar" (PDF). Government of India: Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances & Pensions. 19 March 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 April 2015.

- http://persmin.gov.in/ Webpage of Ministry of Personnel and Public Grievance & Pension

- 125th Dr. Ambedkar Birthday Celebrations Around the World. mea.gov.in

- "Ambedkar Jayanti - Bhim Jayanti - 14 April". Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- "53rd Dhammachakra Pravartan day celebrated in Nagpur". Daily News and Analysis. 28 September 2009. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- Dahat, Pavan (4 October 2015). "Dalits throng Nagpur on Dhammachakra Pravartan Din". The Hindu. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- 1951 to 2011 Census of India

- 2001 and 2011 Census of India

- "Population by religion community – 2011". Census of India, 2011. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015.

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2005). "The 'Solution' of Conversion". Dr Ambedkar and Untouchability: Analysing and Fighting Caste. Orient Blackswan Publisher. pp. 119–131. ISBN 8178241560.

- Zelliot, Eleanor (1978). "Religion and Legitimation in the Mahar Movement". In Smith, Bardwell L. (ed.). Religion and the Legitimation of Power in South Asia. Leiden: Brill. pp. 88–90. ISBN 9004056742.

- Kantowsky, Detlef (1997). Buddhisten in Indien heute, Indica et Tibetica 30, 111

- "बौद्ध बढ़े, चुनावी चर्चे में चढ़े". aajtak.intoday.in (in Hindi). Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- "C-1 Population By Religious Community". Census of India Website. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017.

Further reading

- Doniger, Wendy (2000). Merriam-Webster Encyclopedia of World Religions. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 1378. ISBN 0-87779-044-2.

- Dutt, Nalinaksha (1998). Buddhist Sects in India. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0427-9.

- Elst, K. (2002). Who is a Hindu?: Hindu revivalist views of Animism, Buddhism, Sikhism, and other offshoots of Hinduism. New Delhi: Voice of India.

- Mary Pat Fisher (2008). Living Religions, seventh edition, ISBN 0-13614-105-6.

- Klaus Klostermaier (1999), Buddhism: A Short Introduction, ISBN 978-1-85168-186-0.

- Lamotte, E. (1976). History of Indian Buddhism. Louvain: Peeters Press.

- Swarup, Ram (1984). Buddhism vis-a-vis Hinduism.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Buddhism in India. |