Lepcha people

The Lepcha are also called the Rongkup meaning the children of God and the Rong, Mútuncí Róngkup Rumkup (Lepcha: ᰕᰫ་ᰊᰪᰰ་ᰆᰧᰶ ᰛᰩᰵ་ᰀᰪᰱ ᰛᰪᰮ་ᰀᰪᰱ; "beloved children of the Róng and of God"), and Rongpa (Sikkimese: རོང་པ་), are among the indigenous peoples of Sikkim, India and Nepal, and number around 80,000.[1][2] Many Lepcha are also found in western and southwestern Bhutan, Tibet, Darjeeling, the Mechi Zone of eastern Nepal, and in the hills of West Bengal. The Lepcha people are composed of four main distinct communities: the Renjóngmú of Sikkim; the Dámsángmú of Kalimpong, Kurseong, and Mirik; the ʔilámmú of Ilam District, Nepal; and the Promú of Samtse and Chukha in southwestern Bhutan.[3][4][5]

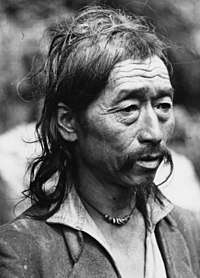

A Lepcha man | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 80,316 (2011) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 76,871 (2011 census)[1] | |

| 3,445 (2011 census)[2] | |

| Languages | |

| Lepcha, Sikkimese (Dranjongke), Dzongkha, Nepali | |

| Religion | |

| Mun, Buddhism | |

Origins

.jpg)

The word Lepcha (endonym Roang kup) is considered to be the anglicised version of the Nepalese word lepche meaning "vile speakers" or "inarticulate speech". This was at first a derogatory nickname but is no longer seen as negative.[6]

The origin of the Lepcha is unknown. They may have originated in Myanmar, Tibet or Mongolia but the Lepcha people themselves firmly believe that they did not migrate to the current location from anywhere and are indigenous to the region.[6] They speak a Tibeto-Burman language which some classify as Himalayish. Based on this, some anthropologists suggest they emigrated directly from Tibet to the north, Japan or from Eastern Mongolia. Others suggest a more complex migration that started in southeast Tibet, a migration to Thailand, Burma, or Japan, then a navigation of the Ayeyarwady River and Chindwin rivers, a crossing of the Patkoi range coming back west, and finally entering ancient India (this supported by Austroasiatic languages substrata in their vocabularies). While migrating westward through India, they are surmised to have passed through southern Bhutan before reaching their final destination near Kanchenjunga. The Lepcha people themselves do not have any tradition of migration, and hence they conclude that they are autochthonous to the region, currently falling under the state of Sikkim, Darjeeling District of West Bengal, eastern Nepal and the southwestern parts of Bhutan. In the Mechi Zone, they form 7% of the population of Ilam District, 2% in Panchthar District, and 10% of the population in Taplejung District. In Sikkim as a whole they are considered to be around 15% of the population of the state.

The Lepcha people were earlier ruled by Pano (King) Gaeboo Achyok. Pano Gaeboo Achyok was instrumental in uniting the Lepcha people and to honour him, the Lepcha people celebrate 20th December of every year as Pano Gaeboo Achyok celebrations day. Pano Gaeboo Achyok extended the Lepcha kingdom from Bhutan in the east to Ilam (Nepal) in the west and from Sikkim to the northern tips of present day Bangladesh.[7]

Language

The Lepcha have their own language, also called Lepcha. It belongs to the Bodish–Himalayish group of Tibeto-Burman languages. The Lepcha write their language in their own script, called Róng or Lepcha script, which is derived from the Tibetan script. It was developed between the 17th and 18th centuries, possibly by a Lepcha scholar named Thikúng Mensalóng, during the reign of the third Chogyal (Tibetan king) of Sikkim.[8] The world's largest collection of old Lepcha manuscripts is found with the Himalayan Languages Project in Leiden, Netherlands, with over 180 Lepcha books.

Clans

Lepchas are divided into many clans (Lepcha: putsho), each of which reveres its own sacred lake and mountain peak (Lepcha: dâ and cú) from which the clan derives its name. While most Lepcha can identify their own clan, Lepcha clan names can be quite formidable, and are often shortened for this reason. For example, Nāmchumú,[9] Simíkmú, and Fonyung Rumsóngmú may be shortened to Namchu, Simik, and Foning, respectively.[10] Some of the name of the clans are "Sada", "Barphungputso", "Rongong", "Karthakmu", "Sungutmu", "Phipon", "Brimu", etc.

Religion

Most Lepchas are Buddhist, a religion brought by the Bhutias from the north, although a large number of Lepchas have today adopted Christianity.[11][12] Some Lepchas have not given up their shamanistic religion, which is known as Mun. In practice, rituals from Mun and Buddhism are frequently observed alongside one another among some Lepchas. For example, ancestral mountain peaks are regularly honoured in ceremonies called cú rumfát.[10] Many rituals involve local species. In Sikkim, Lepchas are known to use over 370 species of animals, fungi, and plants.[13] According to the Nepal Census of 2001, out of the 3,660 Lepcha in Nepal, 88.80% were Buddhists and 7.62% were Hindus. Many Lepchas in the Hills of Sikkim, Darjeeling and Kalimpong are Christians.

Clothing

The traditional clothing for Lepcha women is the ankle-length dumbun, also called dumdyám or gādā ("female dress"). It is one large piece of smooth cotton or silk, usually of a solid color. When it is worn, it is folded over one shoulder, pinned at the other shoulder, and held in place by a waistband, or tago, over which excess material drapes. A contrasting long-sleeved blouse may be worn underneath.[14][15]

The traditional Lepcha clothing for men is the dumprá ("male dress"). It is a multicolored, hand-woven cloth pinned at one shoulder and held in place by a waistband, usually worn over a white shirt and trousers. Men wear a flat round cap called a thyáktuk, with stiff black velvet sides and a multicolored top topped by a knot. Rarely, the traditional cone-shaped bamboo and rattan hats are worn.[14][15]

Dwellings

Traditionally, the Lepcha live in a local house called a li. A traditional home is made out of logs of wood and bamboo and rests around 4 to 5 feet (1.2m to 1.5m) above the ground on stilts. The wooden house with thatched roof is natural air conditioner and eco-friendly. It is interesting to note that the traditional Lepcha house has no nails used in the construction and it is seismic movement friendly since the weight of the house is rested over a large tablets of stones and not planted in the soil.[16]

Subsistence

The Lepchas are mostly agriculturists. They grow oranges, rice, cardamoms, and other foods.[16]

Cuisine

Lepcha cuisine is mild and not as spicy as Indian or Nepalese cuisine. Rice is the staple, while wheat, maize and buckwheat are also used. Fresh fruit and vegetables are used.[17] Khuzom is a traditional Lepcha bread made from buck wheat, millet, and corn or wheat flour. Popular Lepcha dishes include Ponguzom (Rice, fish, vegetable grill), Su zom (Baked meat dish), Thukpa (Noodle, meat and vegetable stew) and Sorongbeetuluk (Rice and nettle porridge).[18]

An alcoholic beverage called Chi or Chhaang is fermented from Millet. Chi also has religious significance as it is given as offering to the Gods during religious ceremonies.[19]

Arts, crafts, and music

The Lepchas are known for their unique weaving and basketry skills.

The Lepcha have a rich tradition of dances, songs, and folktales. The popular Lepcha folk dances are Zo-Mal-Lok, Chu-Faat, Tendong Lo Rum Faat and Kinchum-Chu-Bomsa.[20]

Musical instruments used are Sanga (drum), Yangjey (string instrument), Cymbal, Yarka, Flute and Tungbuk.[20] One popular instrument used by the Lepchas is a four-string lute that is played with a bow.[16]

Marriage customs

The Lepcha are largely an endogamous community.[16]

The Lepcha trace their descent patrilineally. The marriage is negotiated between the families of the bride and the groom. If the marriage deal is settled, the lama will check the horoscopes of the boy and girl to schedule a favourable date for the wedding. Then the boy's maternal uncle, along with other relatives, approach the girl's maternal uncle with a khada, a ceremonial scarf, and one rupee, to gain the maternal uncle's formal consent.[21]

The wedding takes place at noon on the auspicious day. The groom and his entire family leave for the girl's house with some money and other gifts that are handed over to the bride's maternal uncle. Upon reaching the destination, the traditional Nyomchok ceremony takes place, and the bride's father arranges a feast for relatives and friends. This seals the wedding between the couple.[21]

See also

Footnotes

- ORGI. "A-11 Individual Scheduled Tribe Primary Census Abstract Data and its Appendix". www.censusindia.gov.in. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- "National Population and Housing Census 2011" (PDF). UN Statistical Agency.

- Plaisier 2007, p. 1–2.

- SIL 2009.

- NIC-Sikkim.

- West, Barbara A. (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Facts on File. p. 462. ISBN 978-0816071098.

- "B'day bash for Lepcha king". Telegraph India-1. 18 December 2006.

- Plaisier 2007, p. 34.

- A.R.Foning, Lepcha My Vanishing Tribe, Sterling Publishers, 1987, pp. 123-136

- Plaisier 2007, p. 3.

- Joshi 2004, p. 157.

- Semple 2003, p. 123.

- O'Neill, Alexander; et al. (29 March 2017). "Integrating ethnobiological knowledge into biodiversity conservation in the Eastern Himalayas". Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 13 (21): 21. doi:10.1186/s13002-017-0148-9. PMC 5372287. PMID 28356115.

- Plaisier 2007, p. 4.

- Dubey 1980, p. 53, 56.

- Human: The Definitive Visual Guide. New York: Dorling Kindersley. 2004. p. 437. ISBN 0-7566-0520-2.

- "Lepcha". Encyclopedia. 1 August 2019.

- "Some nonfermented ethnic foods of Sikkim in India". Science Direct. December 2014.

- "Chhang: The Beer of the Himalayas". Live History India. 28 May 2017.

- "Lepcha Folk Dances". Sikkim Tourism.

- Gulati 1995, pp. 80–81.

- Cited sources

- Plaisier, Heleen (2007). A Grammar of Lepcha. Tibetan studies library: Languages of the greater Himalayan region. 5. Leiden, The Netherlands; Boston: BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-15525-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lewis, M. Paul, ed. (2009). "Lepcha". Ethnologue: Languages of the World (16th ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- "Lepchas and their Tradition". Official Portal of NIC Sikkim State Centre. National Informatics Centre, Sikkim. 25 January 2002. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- Joshi, H.G. (2004). Sikkim: Past and Present. New Delhi, India: Mittal Publications. ISBN 81-7099-932-4. Retrieved 24 June 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Semple, Rhonda Anne (2003). Missionary Women: Gender, Professionalism, and the Victorian Idea of Christian Mission. Rochester, NY: Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-013-2. Retrieved 24 June 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gulati, Rachna (1995). "Cultural Aspects of Sikkim" (PDF). Bulletin of Tibetology. Gangtok: Namgyal Institute of Tibetology. Retrieved 24 June 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dubey, S. M (1980). S. M. Dubey; P. K. Bordoloi; B. N. Borthakur (eds.). Family, marriage, and social change on the Indian fringe. Cosmo.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lepcha people. |

- "Lepcha script". Omniglot online. Retrieved 17 April 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Plaisier, Heleen (13 November 2010). "Information on Lepcha Language and Culture". Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- Bareh, Hamlet (2001). "The Sikkim Communities". Encyclopaedia of North-East India: Sikkim. New Delhi: Mittal Publications. ISBN 81-7099-794-1.