Buddhism and Western philosophy

Buddhist thought and Western philosophy include several parallels. Before the 20th century, a few European thinkers such as Arthur Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche had engaged with Buddhist thought. Likewise, in Asian nations with Buddhist populations, there were also attempts to bring the insights of Western thought to Buddhist philosophy, as can be seen in the rise of Buddhist modernism.

| Part of a series on |

| Philosophy |

|---|

|

| Branches |

| Periods |

|

| Traditions |

|

Traditions by region Traditions by school Traditions by religion |

| Literature |

|

| Philosophers |

| Lists |

| Miscellaneous |

|

|

After the post-war spread of Buddhism to the West there has been considerable interest by some scholars in a comparative, cross-cultural approach between Eastern and Western philosophy. Much of this work is now published in academic journals such as Philosophy East and West.

Hellenistic philosophy

According to Edward Conze, Greek Skepticism (particularly that of Pyrrho) can be compared to Buddhist philosophy, especially the Indian Madhyamika school.[1] The Pyrrhonian Skeptics' goal of ataraxia (the state of being untroubled) is a soteriological goal similar to nirvana. Pyrrho taught that things are adiaphora (undifferentiated by logical differentia), astathmēta (unstable, unbalanced, not measurable), and anepikrita (unjudged, unfixed, undecidable). This is strikingly similar to the Buddhist Three marks of existence.[2] The Pyrrhonists promoted suspending judgment (epoché) about dogma (beliefs about non-evident matters) as the way to reach ataraxia. This is similar to the Buddha's refusal to answer certain metaphysical questions which he saw as non-conductive to the path of Buddhist practice and Nagarjuna's "relinquishing of all views (drsti)". Adrian Kuzminski argues for direct influence between these two systems of thought. In Pyrrhonism: How the Ancient Greeks Reinvented Buddhism, Kuzminski writes: "its origin can plausibly be traced to the contacts between Pyrrho and the sages he encountered in India, where he traveled with Alexander the Great."[3] According to Kuzminski, both philosophies argue against assenting to any dogmatic assertions about an ultimate metaphysical reality behind our sense impressions as a tactic to reach tranquility and both also make use of logical arguments against other philosophies in order to expose their contradictions.[3]

Hume and Not-Self

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

|

|

The Scottish philosopher David Hume wrote:

"When I enter most intimately into what I call myself, I always stumble on some particular perception or other, of heat or cold, light or shade, love or hatred, pain or pleasure. I never catch myself at any time without a perception, and never can observe any thing but the perception"[4]

According to Hume then there is nothing that is constantly stable which we could identify as the self, only a flow of differing experiences. Our view that there is something substantive which binds all of these experiences together is for Hume merely imaginary. The self is a fiction that is attributed to the entire flow of experiences.[5]

Pain and pleasure, grief and joy, passions and sensations succeed each other, and never all exist at the same time. It cannot, therefore, be from any of these impressions, or from any other, that the idea of self is deriv'd; and consequently there is no such idea...I may venture to affirm of the rest of mankind, that they are nothing but a bundle or collection of different perceptions, which succeed each other with an inconceivable rapidity, and are in a perpetual flux and movement.[4]

This 'Bundle theory' of personal identity is very similar to the Buddhist notion of not-self, which holds that the unitary self is a fiction and that nothing exists but a collection of five aggregates.[5][6] Similarly, both Hume and Buddhist philosophy hold that it is perfectly acceptable to speak of personal identity in a mundane and conventional way, while believing that there are ultimately no such things.[5] Hume scholar Alison Gopnik has even argued that Hume could have had contact with Buddhist philosophy during his stay in France (which coincided with his writing of the Treatise of Human Nature) through the well traveled Jesuit missionaries of the Royal College of La Flèche.[6]

British philosopher Derek Parfit has argued for a reductionist and deflationary theory of personal identity in his book Reasons and Persons. According to Parfit, apart from a causally connected stream of mental and physical events, there are no “separately existing entities, distinct from our brains and bodies”. Parfit concludes that "Buddha would have agreed."[7] Parfit also argues that this view is liberating and leads to increased empathy.

Is the truth depressing? Some may find it so. But I find it liberating, and consoling. When I believed that my existence was such a further fact, I seemed imprisoned in myself. My life seemed like a glass tunnel, through which I was moving faster every year, and at the end of which there was darkness. When I changed my view, the walls of my glass tunnel disappeared. I now live in the open air. There is still a difference between my lives and the lives of other people. But the difference is less. Other people are closer. I am less concerned about the rest of my own life, and more concerned about the lives of others.[8]

According to The New Yorker's Larissa MacFarquhar, passages of Reasons and Persons have been studied and chanted at a Tibetan Buddhist monastery.[9]

Other Western philosophers that have attacked the view of a fixed self include Daniel Dennett (in his paper 'The Self as a Center of Narrative Gravity') and Thomas Metzinger ('The Ego Tunnel').

Idealism

Idealism is the group of philosophies which assert that reality, or reality as we can know it, is fundamentally mental, mentally constructed, or otherwise immaterial. Some Buddhist philosophical views have been interpreted as having Idealistic tendencies, mainly the cittamatra (mind-only) philosophy of Yogacara Buddhism[10] as outlined in the works of Vasubandhu and Xuanzang.[11] Metaphysical Idealism has been the orthodox position of the Chinese Yogacara school or Fǎxiàng-zōng.[12] According to Buddhist philosopher Vasubhandu "The transformation of consciousness is imagination. What is imagined by it does not exist. Therefore everything is representation-only." This has been compared to the Idealist philosophies of Bishop Berkeley and Immanuel Kant. Kant's categories have also been compared to the Yogacara concept of karmic vasanas (perfumings) which condition our mental reality.[11]

Buddhism and German Idealism

Immanuel Kant's Transcendental Idealism has also been compared with the Indian philosophical approach of the Madhyamaka school by scholars such as T. R. V. Murti.[13] Both posit that the world of experience is in one sense a mere fabrication of our senses and mental faculties. For Kant and the Madhyamikas, we do not have access to 'things in themselves' because they are always filtered by our mind's 'interpretative framework'.[14] Thus both worldviews posit that there is an ultimate reality and that Reason is unable to reach it. Buddhologists like Edward Conze have also seen similarities between Kant's antinomies and the unanswerable questions of the Buddha in that "they are both concerned with whether the world is finite or infinite, etc., and in that they are both left undecided."[15]

Arthur Schopenhauer was influenced by Indian religious texts and later claimed that Buddhism was the "best of all possible religions."[16] Schopenhauer's view that "suffering is the direct and immediate object of life"[17] and that this is driven by a "restless willing and striving" are similar to the four noble truths of the Buddha.[18] Schopenhauer promoted the saintly ascetic life of the Indian sramanas as a way to renounce the Will.[19] His view that a single world-essence (The Will) comes to manifest itself as a multiplicity of individual things (principium individuationis) has been compared to the Buddhist trikaya doctrine as developed in Yogacara Buddhism.[19] Finally, Schopenhauer's ethics which are based on universal compassion for the suffering of others can be compared to the Buddhist ethics of Karuṇā.[20]

Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche admired Buddhism, writing that: "Buddhism already has - and this distinguishes it profoundly from Christianity - the self-deception of moral concepts behind it - it stands, in my language, Beyond Good and Evil."[21] Nietzsche saw himself as undertaking a similar project to the Buddha. “I could become the Buddha of Europe,” he wrote in 1883, “though frankly I would be the antipode of the Indian Buddha.”[22] Nietzsche (as well as Buddha) accepted that all is change and becoming, and both sought to create an ethics which was not based on a God or an Absolutist Being.[23] Nietzsche believed that Buddhism's goal of Nirvana was a form of life denying nihilism and promoted what he saw as its inversion, life affirmation and amor fati. According to Benjamin A. Elman, Nietzsche's interpretation of Buddhism as pessimistic and life-denying was probably influenced by his understanding of Schopenhauer's views of eastern philosophy and therefore "he was predisposed to react to Buddhism in terms of his close reading of Schopenhauer."[24] Because of this writes Elman, Nietzsche misinterprets Buddhism as promoting "nothingness" and nihilism, all of which the Buddha and other Buddhist philosophers such as Nagarjuna repudiated, in favor of a subtler understanding of Shunyata.[24]

Antoine Panaïoti argues in Nietzsche and Buddhist philosophy that both of these systems of thought begin by wrestling with the problem of nihilism and that they both develop a therapeutic outlook for dealing with the suffering and anxiety brought about by the crisis of nihilism. While Nietzsche and Buddhism do diverge in some ways, which is why Nietzsche saw himself as an 'Anti-Buddha", Panaïoti stresses the similarity of both systems as paths towards a “vision of great health” that allows one to deal with the impermanent world of becoming by accepting it as it truly is.[25] Ultimately both world views have as their ideal what Panaïoti calls "great health perfectionism" which seeks to remove unhealthy tendencies from human beings and reach an exceptional state of self-development.

Robert G. Morrison has also written on the "ironic affinities" between Nietzsche and Pali Buddhism through close textual comparison, such as that between Nietzsche's 'self-overcoming' (Selbstüberwindung) and the Buddhist concept of mental development (citta-bhavana).[26] Morrison also sees an affinity between the Buddhist concept of tanha, or craving and Nietzsche's view of the will to power as well as in their understandings of personality as a flux of different psycho-physical forces.[27] The similarity between Nietzsche's view of the Ego as flux and the Buddhist concept of anatta is also noted by Benjamin Elman.[24]

David Loy also quotes Nietzsche's views on the subject as "something added and invented and projected behind what there is" (Will to Power 481) and on substance ("The properties of a thing are effects on other 'things' ... there is no 'thing-in-itself.'" WP 557), which are similar to Buddhist nominalist views. Loy however sees Nietzsche as failing to understand that his promotion of heroic aristocratic values and affirmation of will to power is just as much of a reaction to the 'sense of lack' which arises from the impermanence of the subject as what he calls slave morality.[28]

Comparative work has also been done by Japanese interpreters of Nietzsche and Buddhism, such as Nishitani Keiji, in his The Self Overcoming Nihilism (Albany, N.Y., 1990), and Abe Masao in his essays on Nietzsche. In his "The History of Western Philosophy", Bertrand Russell pitted Nietzsche against the Buddha, ultimately criticizing Nietzsche for his promotion of violence, elitism and hatred of compassionate love.

Phenomenology and Existentialism

The German Buddhist monk Nyanaponika Thera wrote that the Buddhist Abhidhamma philosophy "doubtlessly belongs" to Phenomenology and that the Buddhist term dhamma could be rendered as "phenomenon".[29] Likewise, Alexander Piatigorsky sees early Buddhist Abhidhamma philosophy as being a "phenomenological approach".[30]

According to Dan Lusthaus, Buddhism "is a type of phenomenology; Yogacara even moreso."[31] Some scholars reject the idealist interpretation of Yogacara Buddhist philosophy and instead interpret it through the lens of Western Phenomenology which is the study of conscious processes from the subjective point of view.[32]

Christian Coseru argues in his monograph "Perceiving reality" that Buddhist philosophers such as Dharmakirti, Śāntarakṣita and Kamalaśīla "share a common ground with phenomenologists in the tradition of Edmund Husserl and Maurice Merleau-Ponty." That common ground is the notion of the intentionality of consciousness.[33] Coseru compares the concepts of the object aspect (grāhyākāra) and the subject aspect (grāhakākāra) of consciousness to the Husserlian concepts of Noesis and Noema.

Modern Buddhist thinkers who have been influenced by Western Phenomenology and Existentialism include Ñāṇavīra Thera, Nanamoli Bhikkhu, R. G. de S. Wettimuny, Samanera Bodhesako and Ninoslav Ñāṇamoli.

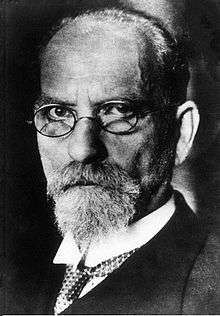

Husserl

Edmund Husserl, the founder of Phenomenology, wrote that "I could not tear myself away" while reading the Buddhist Sutta Pitaka in the German translation of Karl Eugen Neumann.[34][35] Husserl held that the Buddha's method as he understood it was very similar to his own. Eugen Fink, who was Husserl's chief assistant and whom Husserl considered to be his most trusted interpreter said that: "the various phases of Buddhistic self-discipline were essentially phases of phenomenological reduction."[36] After reading the Buddhist texts, Husserl wrote a short essay entitled 'On the discourses of Gautama Buddha' (Über die Reden Gotomo Buddhos) which states:

Complete linguistic analysis of the Buddhist canonical writings provides us with a perfect opportunity of becoming acquainted with this means of seeing the world which is completely opposite of our European manner of observation, of setting ourselves in its perspective, and of making its dynamic results truly comprehensive through experience and understanding. For us, for anyone, who lives in this time of the collapse of our own exploited, decadent culture and has had a look around to see where spiritual purity and truth, where joyous mastery of the world manifests itself, this manner of seeing means a great adventure. That Buddhism - insofar as it speaks to us from pure original sources - is a religio-ethical discipline for spiritual purification and fulfillment of the highest stature - conceived of and dedicated to an inner result of a vigorous and unparalleled, elevated frame of mind, will soon become clear to every reader who devotes themselves to the work. Buddhism is comparable only with the highest form of the philosophy and religious spirit of our European culture. It is now our task to utilize this (to us) completely new Indian spiritual discipline which has been revitalized and strengthened by the contrast.[34]

Fred J Hanna and Lau Kwok Ying both note that when Husserl calls Buddhism "transcendental" he is placing it on the same level as his own transcendental phenomenology.[35] Also, that Husserl called Buddhism a "great adventure" is significant, since he referred to his own philosophy in that way as well - as a methodology which changes the way one views reality which also brings about personal transformation.[34] Husserl also wrote about Buddhist philosophy in an unpublished manuscript "Sokrates - Buddha" in which he compared the Buddhist philosophical attitude with the Western tradition. Husserl saw a similarity between the Socratic good life lived under the maxim "Know yourself" and the Buddhist philosophy, he argues that they both have the same attitude, which is a combination of the pure theoretical attitude of the sciences and the pragmatic attitudes of everyday life. This third attitude is based on "a praxis whose aim is to elevate humankind through universal scientific reason."[35]

Husserl also saw a similarity between Buddhist analysis of experience and his own method of epoche which is a suspension of judgment about metaphysical assumptions and presuppositions about the 'external' world (assumptions he termed 'the naturalistic attitude). However Husserl also thought that Buddhism has not developed into a unifying science which can unite all knowledge since it remains a religious-ethical system and hence it is not able to qualify as a full transcendental phenomenology.[35]

According to Aaron Prosser, "The phenomenological investigations of Siddhartha Gautama and Edmund Husserl arrive at the exact same conclusion concerning a fundamental and invariant structure of consciousness. Namely, that object-directed consciousness has a transcendental correlational intentional structure, and that this is fundamental -- in the sense of basic and necessary--to all object-directed experiences."[37]

Heidegger

According to Reinhard May and Graham Parkes, Heidegger may have been influenced by Zen and Daoist texts.[38][39] Some of Martin Heidegger's philosophical terms, such as Ab-grund (void), Das Nichts (the Nothing) and Dasein have been considered in light of Buddhist terms which express similar ideas such as Emptiness.[40][41] Heidegger wrote that: “As void [Ab-grund], Being ‘is’ at once the nothing [das Nichts] as well as the ground.”[42] Heidegger's "Dialogue on Language", has a Japanese friend (Tezuka Tomio) state that "to us [Japanese] emptiness is the loftiest name for what you mean to say with the word ‘Being’”[43] Heidegger's critique of metaphysics has also been compared to Zen's radical anti-metaphysical attitude.[43] William Barrett held that Heidegger's philosophy was similar to Zen Buddhism and that Heidegger himself had confirmed this after reading the works of DT Suzuki.[43]

Existentialism

Jean-Paul Sartre believed that consciousness lacks an essence or any fixed characteristics and that insight into this caused a strong sense of Existential angst or Nausea. Sartre saw consciousness as defined by its ability of negation, this happens because whenever consciousness becomes conscious of something it is aware of itself not being that intentional object. Consciousness is nothingness because all being-in-itself - the entire world of objects - is outside of it.[44] Furthermore, for Sartre, being-in-itself is also nothing more than appearance, it has no essence.[45] This conception of the self as nothingness and of reality as lacking any inherent essence has been compared to the Buddhist concept of Emptiness and Not-self.[46][47] Just like the Buddhists rejected the Hindu concept of Atman, Sartre rejected Husserl's concept of the transcendental ego.

Merleau-Ponty's phenomenology has been said to be similar to Zen Buddhism and Madhyamaka in that they all hold to the interconnection of the self, body and the world (the "lifeworld"). The unity of body and mind (shēnxīn, 身心) expressed by the Buddhism of Dogen and Zhanran and Merleau-Ponty's view of the corporeity of consciousness seem to be in agreement. They both hold that the conscious mind is inherently connected to the body and the external world and that the lifeworld is experienced dynamically through the body, denying any independent Cartesian Cogito.[48]

The German existentialist Karl Jaspers also wrote on the philosophy of the Buddha in his "The Great Philosophers" (1975). He recommended that Western Christians could learn from the Buddha, praised his cosmopolitanism and the flexibility and relatively non-dogmatic worldview of Buddhism.[49]

Kyoto School

The Kyoto School was a Japanese philosophical movement centered around Kyoto University that assimilated western philosophical influences (such as Kant and Heidegger) and Mahayana Buddhist ideas to create a new original philosophical synthesis.[50] Its founder, Nishida Kitaro (1870–1945) developed the central concept associated with the Kyoto school, that is the concept of “Absolute Nothingness” (zettai-mu) which is related to the Zen Buddhist term Mu (無) as well as Shunyata.[50] Nishida saw the Absolute nature of reality as Nothingness, a "formless", "groundless ground" which envelops all beings and allows them to undergo change and pass away.[50]

Buddhism and Process philosophy

The process philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead has several convergent points with Buddhist philosophy.[51] Whitehead saw reality as an impermanent constant process of flux and denied that objects had any real substance within them, but rather were ever changing occasions. This is similar to the Buddhist concepts of the impermanence and emptiness.[52] Whitehead also held that each one of these processes was never independent, but was interrelated and dependent all prior occasions, and this feature of reality which he called 'creativity' has been compared to dependent origination which holds that all events are conditioned by multiple past causes.[51][52] Like Buddhism, Whitehead also held that our understanding of the world is usually mistaken because we hold to the ‘fallacy of misplaced concreteness’ in seeing constantly changing processes as having fixed substances.[52] Buddhism teaches that suffering and stress arises from our ignorance to the true nature of the world. Likewise, Whitehead held that the world is "haunted by terror" at this process of change. "The ultimate evil in the temporal world...lies in the fact that the past fades, that time is a ‘perpetual perishing’" (PR, p. 340). In this sense, Whitehead's concept of "evil" is similar to the Buddhist viparinama-dukkha, suffering caused by change.[51] Whitehead also had a view of God which has been likened to the Mahayana theory of the Trikaya as well as the Bodhisattva ideal.[51]

Panpsychism and Buddha-nature

Panpsychism is the view that mind or soul is a universal feature of all things; this has been a common view in western philosophy going back to the Presocratics and Plato. According to D. S. Clarke, panpsychist and panexperientialist aspects can be found in the Huayan and Tiantai (Jpn. Tendai) Buddhist doctrines of Buddha nature, which was often attributed to inanimate objects such as lotus flowers and mountains.[53]

Wittgenstein

Ludwig Wittgenstein held a therapeutic view of philosophy which according to K.T. Fann has "striking resemblances" to the Zen Buddhist conception of the dharma as a medicine for abstract linguistic and philosophical confusion.[54] C. Gudmunsen in his Wittgenstein and Buddhism argues that "much of what the later Wittgenstein had to say was anticipated about 1,800 years ago in India." In his book, Gudmunsen mainly compares Wittgenstein's later philosophy with Madhyamaka views on the emptiness of thought and words.[55] One of Wittgenstein's students, the Sri Lankan philosopher KN Jayatilleke, wrote Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge which interpreted the epistemology of the early Buddhist texts analytically.

Many modern interpreters of Nagarjuna (Jay Garfield, CW Huntington) take a Wittgensteinian or Post-Wittgensteinian critical model in their work on Madhyamaka Buddhist philosophy.[56] Ives Waldo writes that Nagarjuna's criticism of the idea of svabhava (own-being) "directly parallels Wittgenstein's argument that a private language (an empiricist language) is impossible. Having no logical links (criteria) to anything outside their defining situation, its words must be empty of significance or use."[57]

See also

References

- Conze, Edward. Buddhist Philosophy and Its European Parallels Archived 7 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Philosophy East and West 13, p.9-23, no.1, January 1963. University press of Hawaii.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2015). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia (PDF). Princeton University Press. p. 28. ISBN 9781400866328.

- Kuzminski, Pyrrhonism How the Ancient Greeks Reinvented Buddhism; for a recent study see Halkias "The Self-immolation of Kalanos and other Luminous Encounters among Greeks and Indian Buddhists in the Hellenistic World" Jocbs. 2015 (8): 163–186. https://www.academia.edu/12679460/The_Self-immolation_of_Kalanos_and_other_Luminous_Encounters_Among_Greeks_and_Indian_Buddhists_in_the_Hellenistic_World

- Hume, David. A Treatise of Human Nature, Book I Part IV Section VI: Of Personal Identity

- Giles, James. The No-Self Theory: Hume, Buddhism, and Personal Identity, Philosophy East and West, Vol. 43, No. 2 (Apr., 1993), pp. 175-200, University of Hawai'i Press.

- Gopnik, Alison. Could David Hume Have Known about Buddhism? Charles Francois Dolu, the Royal College of La Flèche, and the Global Jesuit Intellectual Network. Hume Studies, Volume 35, Number 1&2, 2009, pp. 5–28.

- Parfit, Reasons and Persons 1984, p 273

- Parfit, Reasons and Persons 1984, pp. 280-81

- MacFarquhar, Larissa. HOW TO BE GOOD, An Oxford philosopher thinks he can distill all morality into a formula. Is he right? 2011

- Tola & Dragonetti, Philosophy of mind in the Yogacara Buddhist idealistic school, History of Psychiatry, 16(4): 453–465. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 18 August 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Butler, Sean. Idealism in Yogācāra Buddhism, The Hilltop Review, Western Michigan University.

- Chan, Wing-cheuk, Yogacara Buddhism and Sartre’s Phenomenology.

- T. R. V. Murti, The Central Philosophy of Buddhism

- Burton, David. Buddhism, Knowledge and Liberation: A Philosophical Study, 107.

- Conze, Edward. Spurious Parallels to Buddhist Philosophy Archived 8 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Philosophy East and West 13, no.2, pp105-115 January 1963.

- Urs App, Richard Wagner and Buddhism, pg 17

- Schopenhauer, On the Sufferings of the world

- oregonstate.edu page on Schopenhauer & Buddhism http://oregonstate.edu/instruct/phl201/modules/Philosophers/Schopenhauer/schopenhauer.html

- Wicks, Robert, "Arthur Schopenhauer", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2011 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2011/entries/schopenhauer/>

- Hutton, Kenneth Compassion in Schopenhauer and Śāntideva. Journal of Buddhist Ethics Vol. 21 (2014) and (2009) Ethics in Schopenhauer and Buddhism. PhD thesis, University of Glasgow http://theses.gla.ac.uk/912/.

- Nietzsche, The Anti-Christ, R. J. Hollingdale (Trans and Ed.) (Harmondsworth: Penguin), No. 20, p.129.

- Panaïoti, Antoine; Nietzsche and Buddhist Philosophy, p 2

- Panaïoti, Antoine; Nietzsche and Buddhist Philosophy, p 3

- Elman, Benjamin A. Nietzsche and Buddhism, Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 44, No. 4. (Oct. - Dec., 1983), pp. 671-686.

- Panaïoti, Antoine; Nietzsche and Buddhist Philosophy, p 49

- MORRISON, ROBERT G. Nietzsche and Buddhism: A Study in Nihilism and Ironic Affinities. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997

- Morrison, Robert G. Nietzsche and Buddhism: A Study in Nihilism and Ironic Affinities; Reviewed by Loy, David R. Asian Philosophy Vol. 8, No. 2 (July 1998) pp. 129-131 Copyright 1998 Journals Oxford Ltd. (UK), http://enlight.lib.ntu.edu.tw/FULLTEXT/JR-EPT/loy.htm

- Loy, David; Beyond good and evil? A Buddhist critique of Nietzsche. Asian Philosophy Vol. 6, No. 1 (March, 1996) pp. 37-58, http://ccbs.ntu.edu.tw/FULLTEXT/JR-ENG/loy1.htm

- Nyanaponika Thera, Abhidhamma studies, p20.

- A. Piatigorsky The Buddhist philosophy of thought. — Totowa, N. J., 1984

- Dan Lusthaus. Buddhist Phenomenology: A Philosophical Investigation of Yogacara Buddhism and the Ch'eng Wei-shih Lun. Curzon Critical Studies in Buddhism Series. London: Routledge, 2002. Page viii

- Sharf, R.H. Is Yogācāra Phenomenology? Some Evidence from the Cheng weishi lun, Indian Philos (2016) 44: 777. doi:10.1007/s10781-015-9282-7

- Coseru, Christian; Perceiving Reality: Consciousness, Intentionality, and Cognition in Buddhist Philosophyu

- Hanna, Fred; Husserl on the Teachings of the Buddha; in The Humanistic Psychologist 23(3):365-372 · September 1995.

- Lau Kwok Ying, Husserl, Buddhism and the problematic crisis of the European sciences; http://www.cuhk.edu.hk/rih/phs/events/200405_PEACE/papers/LAUKwokYing.PDF

- Cairns, D. Conversations with Husserl and Fink, p. 50; The Hague: Nijhoff.

- Prosser, Aaron; Siddhartha, Husserl, and Neurophenomenology, Journal of Consciousness Studies, Volume 20, Numbers 5-6, 2013, pp. 151-170(20)

- Parkes, Graham. Heidegger and Asian Thought

- May, Reinhard, Heidegger's Hidden Sources: East-Asian Influences on his Work

- Rolf von Eckartsberg and Ronald S. Valle, Heideggerian Thinking and the Eastern Mind.

- Wing-cheuk Chan, HEIDEGGER AND CHINESE BUDDHISM

- Backman, Jussi. THE ABSENT FOUNDATION HEIDEGGER ON THE RATIONALITY OF BEING.

- Storey, David “Zen in Heidegger’s Way”, Journal of East-West philosophy.

- Phra Medidhammaporn (Prayoon Mererk): Sartre’s Existentialism and Early Buddhism. Publisher: Buddhadhamma Foundation.

- H. Lee, Sander. Notions of Selflessness in Sartrean Existentialism and Theravadin Buddhism. http://www.bu.edu/wcp/Papers/Reli/ReliLee.htm

- Steven William Laycock, Nothingness and Emptiness: A Buddhist Engagement With the Ontology of Jean-Paul Sartre

- Gokhale,Sarah. Empty Selves: A Comparative Analysis of Mahayana Buddhism, Jean-Paul Sartre’s Existentialism, and Depth Psychology.

- Jin Y. Park, Gereon Kopf (editors). Merleau-Ponty and Buddhism, pg 4, pg84.

- Helmut Wautischer, Alan M. Olson, Gregory J. Walters; Philosophical Faith and the Future of Humanity, p 415-417

- Davis, Bret W., "The Kyoto School", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2010 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2010/entries/kyoto-school/>.

- Inada, Kenneth K. The metaphysics of Buddhist experience and the Whiteheadian encounter, Philosophy East and West Vol. 25/1975.10. P.465-487 http://ccbs.ntu.edu.tw/FULLTEXT/JR-PHIL/inada3.htm Archived 19 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- McFarlane, Thomas J. Process and Emptiness: A Comparison of Whitehead’s Process Philosophy and Mahayana Buddhist Philosophy.

- Clarke, D.S. Panpsychism: past and recent selected readings, pg 39.

- K. T. Fann, Wittgenstein's Conception of Philosophy, pg110

- Gudmunsen, Chris Wittgenstein and Buddhism, 1977, p. 113.

- Rosenquist, Tina. Demystifying the saint, Jay L Garfield's rational reconstruction of Nagarjuna's Madhyamaka as the epitome of cross-cultural philosophy.

- Ives Waldo, "Naagaarjuna and Analytic Philosophy, "Philosophy East and West 25, no. 3 (July p. 169 1975): 281-290.