Adrian helmet

The M15 Adrian helmet (French: Casque Adrian) was a combat helmet issued to the French Army during World War I. It was the first standard helmet of the French Army and was designed when millions of French troops were engaged in trench warfare, and head wounds from the falling shrapnel generated by indirect fire became a frequent cause of battlefield casualties. Introduced in 1915, it was the first modern steel helmet[1][2] and it served as the basic helmet of many armies well into the 1930s. Initially issued to infantry soldiers, in modified form they were also issued to cavalry and tank crews. A subsequent version, the M26, was used during World War II.

History

At the outbreak of World War I in August 1914 soldiers in the French Army wore the standard kepi cap, which provided no protection against injury. The early stages of trench warfare proved that even basic protection of the head would result in a significantly lower mortality rate among front-line soldiers. By the beginning of 1915 a rudimentary steel skull-cap (calotte métallique, cervelière) was being issued to be worn under the kepi.[3]

Consequently, the French staff ordered development of a metal helmet that could protect soldiers from the shrapnel of exploding artillery shells. Since soldiers in trenches were also vulnerable to shrapnel exploding above their heads, a deflector crest was added along the helmet's axis. Branch insignia in the form of a grenade for line infantry and cavalry, a bugle horn for chasseurs, crossed cannon for artillery, an anchor for colonial troops and a crescent for North African units was attached to the front.[4] Contrary to common misconception, the M15 helmet was not designed to protect the wearer from direct impact by rifle or machine gun bullets. The resulting headgear was credited to Intendant-General August-Louis Adrian.[5]

The helmet adopted by the army was made of mild steel[6] and weighed only 0.765 kg (1 lb 11.0 oz)), which made it lighter and less protective than the contemporary British Brodie helmet and the German Stahlhelm. Orders were placed for the helmets in the spring of 1915 and started being issued by July. By September, all frontline troops in France were issued with the helmet.[7] The helmet was surprisingly complex to produce with seventy stages involved in its production, not including those required to prepare the metal. It's slot for the badges and the distinctive crest took additional time to manufacture, while also adding a hundred grams of weight. However, the helmet was deliberately designed this way to evoke the artistic style of the highly popular military artist Édouard Detaille, which helped raise the morale of the troops. Indeed French troops identified quite closely with their helmets. The helmet's light weight was also better suited to France's emphasis on mobility and was easier for soldiers to wear for extended periods.[8]

From late 1915, a cloth cover for the helmet was issued, in khaki or light blue, to prevent reflection. However, it was found that if the helmet was pierced by shell splinters, pieces of dirty cloth were carried into the wound, which increased the risk of infection. Consequently, in mid-1916 an order was issued that the covers should be discarded. By the end of World War I, the Adrian had been issued to almost all infantry units fighting with the French Army. It was also used by some of the American divisions fighting in France, including the African-American 369th Infantry Regiment, commonly known as the Harlem Hellfighters,[9][10] and the Polish forces of Haller's Blue Army.[11] The French Gendarmerie mobile adopted a dark blue version in 1926,[12] and continued to wear it into the 1960s, well after the regular army had discarded it.

The helmet proved to be fairly effective against shrapnel and it was cheap and easy to manufacture. As a consequence, more than twenty million Adrian helmets were produced.[7] They were widely adopted by other countries including Belgium, Brazil, China, Czechoslovakia,[13] Greece, Italy (including license-built versions), Japan, Luxembourg, Mexico, Morocco, Peru, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Spain, Siam, United States, U.S.S.R., and Yugoslavia, each of these nations adding its own insignia to the front of the helmet.[10]

However, because the new steel helmets offered little protection against actual bullets, they were reportedly often among the first pieces of equipment to be abandoned by soldiers on the battlefield.[11] It was also discovered that the badge placed on the front of helmets impaired the strength of the helmet because of the two slots required. This perceived weakness made several armies remove their national insignia altogether. Early helmets were painted "horizon-blue" (light blue-grey) for French troops and khaki for colonial forces. Those made after 1935 are usually painted khaki, reflecting the French army movement to a more camouflaged uniform in the 1930s.

In 1926 the Adrian helmet was modified by being constructed of stronger steel and simplified by having the main part of the helmet stamped from one piece of metal, and therefore without the joining rim around the helmet that characterizes the M15. The large ventilation hole under the comb, which had been a weak point of the old design, was also replaced with a series of small holes. The M26 helmet continued in use with the French Army until after World War II, and was also used by the French police up to the 1970s. During the interwar period Belgium began to produce their own domestically made M26 Adrians and exported them around the globe. These helmets can be distinguished from their French counterparts, because they have a slightly different comb and a wider rim. In other countries the Adrian-type helmets were also in use with the fire-fighting units, railway guards or marine infantry (e.g. Japan's SNLF). Adrian helmets are still prized by collectors today. In 1940, Mexico began to produce M26 helmets locally after shipments from France stopped due to the German occupation. A crestless version was produced in small numbers as well.[14]

Usage

In December 1915, Winston Churchill (later to become Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940–1945), while serving as a major with the British Army's Grenadier Guards, was presented with an Adrian helmet by the French General Émile Fayolle. He is seen wearing it in photographs and in a portrait painted by Sir John Lavery.[15]

Gallery

A smaller version of the Adrian helmet for tank crew members

A smaller version of the Adrian helmet for tank crew members- French sentry's helmet designed to protect the face, invented by Dr. Polack, medical officer; the Verdun Memorial, Fleury-devant-Douaumont, France

Wz.15 (Polish version of the Adrian helmet) as part of a soldier's grave at Powązki cemetery in Warsaw

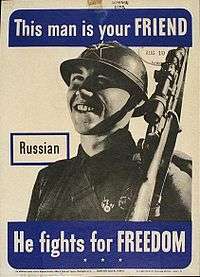

Wz.15 (Polish version of the Adrian helmet) as part of a soldier's grave at Powązki cemetery in Warsaw World War II recognition card featuring a Soviet soldier wearing the Adrian helmet with red star insignia

World War II recognition card featuring a Soviet soldier wearing the Adrian helmet with red star insignia- Serbian M15 Adrian helmet from World War I

- Statue of Albert I of Belgium with Adrian helmet distinguished by lion's head insignia

A 1926 model of the Adrian helmet

A 1926 model of the Adrian helmet

Notes and references

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Adrian helmets. |

- "Military Trader". Archived from the original on 2011-07-26. Retrieved 2011-01-17.

- Military headgears Archived May 27, 2012, at Archive.today

- Bertin, Pierre. Le Fantassin de France. p. 205. ISBN 2-905393-11-4.

- Andre Jouineau, page 8 "Officers and Soldiers of the French Army 1918", ISBN 978-2-35250-105-3

- Militaria: The French Adrian Helmet

- Later, French and license-built Italian versions were made in even lighter-weight aluminium, probably for parade use.

- Doyle, Peter (2016-05-10). First World War in 100 Objects. The History Press. ISBN 9780750954938.

- Tenner, Edward, and Edward Tenner. Our own devices: The past and future of body technology. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003, pp.250-251

- Notably the American Expeditionary Force's 1st and 3rd Divisions

- Adrian au Spectra (2005). "Heaumes Page" (in French). Archived from the original on 30 November 2006. Retrieved 2006-11-01.

- Bolesław Rosiński (2005). "Hełm wz.15". bolas.prv.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2007-10-16. Retrieved 2006-11-02.

- Page 42 Militaria Magazine April 2014,

- Brayley, Martin (2008). Tin Hats to Composite Helmets. Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire: The Crowood Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-84797-024-4.

- "Mexico". Maharg Press. Retrieved 2019-02-08.

- Rankin, Nicholas Churchill's Wizards: The British Genius for Deception 1914-1945, page 83.

Bibliography

- Jacek Kijak; Bartłomiej Błaszkowski (2004). Hełmy Wojska Polskiego 1917-2000 (in Polish). Warsaw: Bellona. p. 128. ISBN 83-11-09636-8.