Malabar Coast

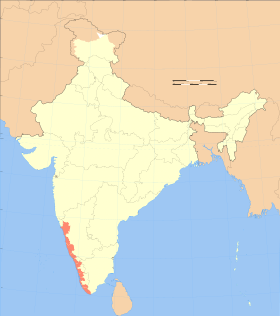

The Malabar Coast (also known simply as Malabar) is a region of the southwestern shoreline of the mainland Indian subcontinent. Geographically, it comprises the wettest regions of southern India, as the Western Ghats intercept the moisture-laden monsoon rains, especially on their westward-facing mountain slopes. Culturally, it covers the northern part of the Kerala state along with Tulu Nadu and Kodagu district, from the Arabian Sea inland to the Western Ghats. The term is sometimes used to refer to the entire Indian coast from the western coast of Konkan to the tip of the subcontinent at Kanyakumari.[1]

Malabar | |

|---|---|

Region | |

Kadalur Point Lighthouse near Koyilandy | |

| Country | India |

| State | Kerala |

| • Density | 816/km2 (2,110/sq mi) |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Malayalam, English |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| ISO 3166 code | IN-KL |

| Vehicle registration | KL-01 to KL-71 |

| No. of districts | 14 |

| Climate | Tropical (Köppen) |

Definitions

The term Malabar Coast, in historical contexts, refers to India's southwestern coast, which lies on the narrow coastal plain of Karnataka and Kerala states between the Western Ghats range and the Arabian Sea.[1] The coast runs from south of Goa to Kanyakumari on India's southern tip. India's southeastern coast is called the Coromandel Coast.[2]

In ancient times the term Malabar was used to denote the entire south-western coast of the Indian peninsula. The region formed part of the ancient kingdom of Chera until the early 12th century. Following the breakup of the Chera Kingdom, the chieftains of the region proclaimed their independence. Notable among these were the Kolathiris, Travancore, Zamorins of Calicut, the Coylot Wanees Country of northeast and coastal Ceylon (including Puttalam), Valluvokonathiris of Valluvanad.

The name Malabar Coast is sometimes used as an all-encompassing term for the entire Indian coast from Konkan to the tip of the subcontinent at Kanyakumari.[1] This coast is over 845 km (525 mi) long and stretches from the coast of southwestern Maharashtra, along the region of Goa, through the entire western coast of Karnataka and Kerala, and up to Kanyakumari. It is flanked by the Arabian Sea on the west and the Western Ghats on the east. The southern part of this narrow coast is referred to as the South Western Ghats moist deciduous forests.[3]

Malabar is also used by ecologists to refer to the tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests of southwestern India (present-day Kerala).

Etymology

The whole name Malabar is first attested in Arabic (as malabaar) in the writing of Al Biruni. The second part of the name is thought by scholars to be the Arabic word barr ('continent') or its Persian relative bar ('country'). The first element of the name, however, is attested already in the Topography written by Cosmas Indicopleustes in the sixth century CE. This mentions a pepper emporium called Male, which clearly gave its name to Malabar ('the country of Male'). The name male is thought to come from the Tamil word mala ('hill').[4][5]

Alternative etymologies have been proposed, however, for example that Malabar derives from the Malayalam word Mala-Baram, 'hill slope' (since Malayalam varam means 'slope' or 'side of a hill').

Geography

Physical geography

The term Malabar Coast is sometimes used as an all-encompassing term for the entire Indian coast from the western coast of Konkan to the tip of the subcontinent at Cape Comorin. It is over 525 miles or 845 kilometers long. It spans from the south-western coast of Maharashtra and goes along the coastal region of Goa, through the entire western coast of Karnataka and Kerala and reaches till Kanyakumari. It is flanked by the Arabian Sea on the west and the Western Ghats on the east. The Southern part of this narrow coast is the South Western Ghats moist deciduous forests. Climate-wise, the Malabar Coast, especially on its westward-facing mountain slopes, comprises the wettest region of southern India, as the Western Ghats intercept the moisture-laden Southwest monsoon rains.

Malabar rainforests

The Malabar rainforests include these ecoregions recognized by biogeographers:

- the Malabar Coast moist forests formerly occupied the coastal zone, up to the 250 meter in elevation (but 95% of these forests no longer exist)

- the South Western Ghats moist deciduous forests grow at intermediate elevations

- the South Western Ghats montane rain forests cover the areas above 1000 meters

The Monsooned Malabar coffee bean comes from this area.

Port cities

The Malabar Coast featured (and in some instances still does) several historic port cities. Notable among these were/are Naura, Vizhinjam, Muziris, Nelcynda, Beypore and Thundi (near Kadalundi) during ancient times, and Kozhikode (Calicut), Cochin in the medieval period, and have served as centers of the Indian Ocean trade for millennia.

Because of their orientation to the sea and to maritime commerce, the Malabar coast cities feel very cosmopolitan, and have been home to some of the first groups of Jews (known today as Cochin Jews), Syrian Christians (known as Saint Thomas Christians), Muslims (presently known as Mappilas), and Anglo-Indians in India.[6][7]

History

Ancient and medieval history

The Malabar Coast, throughout recorded history from about 3000 BC, had been a major trading center in commerce with Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, Rome, Jerusalem and the Arab world.[8][9] Its most famous ports (both defunct and functional) were Naura (Kannur), Balita (Vizhinjam), Kochi, ponnani, Calicut, Mangalore, and the most popular among them Muziris.[10][11] The Oddeway Torre settlement (part of Danish India) has served as a center of the Indian Ocean trade for centuries.[12]

During Ming China's treasure voyages in the early 15th century, Admiral Zheng He's fleet often landed at the Malabar Coast.[13] Soon after, Vasco da Gama landed near Calicut in 1498, establishing a sea route between India and Europe. Portugal became the first of several European maritime empires to grow rich from the spice trade with this area.

British colonialism: Malabar District

After the Anglo-Mysore wars, the region was organized into a district of Madras Presidency. The British district included the present-day districts of Kannur, Kozhikode, Wayanad, Malappuram, much of Palakkad (Excluding Chittur taluk) and some parts of Thrissur (Chavakkad Taluk). The administrative headquarters was at Calicut (Kozhikode).

Malabar District, a part of the ancient Malabar (or Malabar Coast) was a part of the British East India Company-controlled state. It included the northern half of the state of Kerala and some coastal regions of present-day Karnataka. The area is predominantly Hindu, but a part of Kerala's Muslim population (Mappila) also live in this area, as well as a sizable ancient Christian population.[14] Kozhikode is considered as the capital of Malabar. During the British rule, Malabar's chief importance lay in producing pepper.[15] The area was divided into two categories as North and South. North Malabar comprises present Kasaragod and Kannur Districts, Mananthavady Taluk of Wayanad District and Vatakara and Koyilandy Taluks of Kozhikode District. The left-over area is South Malabar aka Eranad Taluk which comes under present Malappuram District, Palakkad District and Chavakkad taluk of Thrissur district.

After Indian independence

With India's independence, Madras presidency became Madras State, which was divided along linguistic lines on 1 November 1956, whereupon Kasaragod region was merged with the Malabar immediately to the north and the state of Travancore-Cochin to the south to form the state of Kerala. Before that, Kasaragod was a part of South Canara district of Madras Presidency.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Malabar Coast. |

- Coromandel Coast

- Dutch Malabar

- Malabar (disambiguation)

- Malabar District

- Malappuram District

- Portuguese Empire

- Portuguese India

References

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Malabar. |

- Britannica

- Map of Coromandel Coast Archived 10 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine on a website dedicated to the East Indian Campaign (1782–1783), an offshoot of the American war of independence.

- Tipu Sultan - the Tyrant of Mysore, Sandeep Balakrishna, (Chapter 10) pg 109

- C. A. Innes and F. B. Evans, Malabar and Anjengo, volume 1, Madras District Gazetteers (Madras: Government Press, 1915), p. 2.

- M. T. Narayanan, Agrarian Relations in Late Medieval Malabar (New Delhi: Northern Book Centre, 2003), xvi-xvii.

- The Jews of India: A Story of Three Communities by Orpa Slapak. The Israel Museum, Jerusalem. 2003. p. 27. ISBN 965-278-179-7.

- The Clash of Cultures in Malabar : Encounters, Conflict and Interaction with European Culture, 1498-1947 Korean Minjok Leadership Academy, Myeong, Do Hyeong, Term Paper, AP World History Class, July 2012

- Pradeep Kumar, Kaavya (28 January 2014). "Of Kerala, Egypt, and the Spice link". The Hindu. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- Cyclopaedia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia. Ed. by Edward Balfour (1871), Second Edition. Volume 2. p. 584.

- "Artefacts from the lost Port of Muziris." The Hindu. 3 December 2014.

- "Muziris, at last?" R. Krishnakumar, www.frontline.in Frontline, 10–23 April 2010.

- The spicy history of Malabar Archived 10 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine including a bibliography of sources on the spice trade via the Malabar coast

- Chan, Hok-lam (1998). "The Chien-wen, Yung-lo, Hung-hsi, and Hsüan-te reigns, 1399–1435". The Cambridge History of China, Volume 7: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 233–236. ISBN 9780521243322.

- "Kerala. Encyclopædia Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 8 June 2008.

- Pamela Nightingale, ‘Jonathan Duncan (bap. 1756, d. 1811)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2009

Further reading

- Panikkar, K. M. (1929). Malabar and the Portuguese: being a history of the relations of the Portuguese with Malabar from 1500 to 1663.

- Panikkar, K. M. (1931). Malabar and the Dutch.

- Panikkar, K. M. (1953). Asia and Western dominance, 1498-1945. London: G. Allen and Unwin.