Digital divide

A digital divide is any uneven distribution in the access to, use of, or impact of information and communications technologies (ICT) between any number of distinct groups, which can be defined based on social, geographical, or geopolitical criteria, or otherwise.[1]

| Internet |

|---|

An Opte Project visualization of routing paths through a portion of the Internet |

|

|

The term digital divide was first coined by Lloyd Morrisett, when he was president of the Markle Foundation (Hoffman, et al., 2001). Traditionally considered to be a question of having or not having access,[2] with a global mobile phone penetration of over 95%[3] it is becoming a relative inequality between those who have more and less bandwidth[4] and more or fewer skills.[5][6][7][8]

- Who is the subject that connects: individuals, organizations, enterprises, schools, hospitals, countries, etc.

- Which characteristics or attributes are distinguished to describe the divide: income, education, age, geographic location, motivation, reason not to use, et Cetra.

- How sophisticated is the usage: mere access, retrieval, interactivity, intensive and extensive in usage, innovative contributions, etc.

- To what does the subject connect: fixed or mobile, Internet or telephone, digital TV, broadband, etc.[9]

Different authors focus on different aspects, which leads to a large variety of definitions of the digital divide. "For example, counting with only 3 different choices of subjects (individuals, organizations, or countries), each with 4 characteristics (age, wealth, geography, sector), distinguishing between 3 levels of digital adoption (access, actual usage and effective adoption), and 6 types of technologies (fixed phone, mobile... Internet...), already results in 3x4x3x6 = 216 different ways to define the digital divide. Each one of them seems equally reasonable and depends on the objective pursued by the analyst".[10] The "digital divide" is also referred to by a variety of other terms which have similar meanings, though may have a slightly different emphasis: digital inclusion,[11] digital participation,[12] basic digital skills,[13] media literacy [14] and digital accessibility.[15]

The National Digital Inclusion Alliance, a US-based nonprofit organization, has found the term "digital divide" to be problematic, since there are a multiplicity of divides. Instead, they chose to use the term "digital inclusion," providing a definition: Digital Inclusion refers to the activities necessary to ensure that all individuals and communities, including the most disadvantaged, have access to and use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs). This includes 5 elements: 1) affordable, robust broadband internet service; 2) internet-enabled devices that meet the needs of the user; 3) access to digital literacy training; 4) quality technical support; 5) applications and online content designed to enable and encourage self-sufficiency, participation and collaboration.[16]

Some people are concerned that people without access to the internet and other information and communication technologies will be disadvantaged, as they are unable or less able to shop online, search for information online, or learn skills needed for technical jobs. This results in programs to give computers and related services to people without access. However, a reverse divide is also happening, as poor and disadvantaged children and teenagers spend more time using digital devices for entertainment and less time interacting with people face-to-face compared to children and teenagers in well-off families.[17]

The divide between differing countries or regions of the world is referred to as the global digital divide,[1][18] examining this technological gap between developing and developed countries on an international scale.[19] The divide within countries (such as the digital divide in the United States) may refer to inequalities between individuals, households, businesses, or geographic areas, usually at different socioeconomic levels or other demographic categories.

Means of connectivity

Infrastructure

The infrastructure by which individuals, households, businesses, and communities connect to the Internet address the physical mediums that people use to connect to the Internet such as desktop computers, laptops, basic mobile phones or smartphones, iPods or other MP3 players, gaming consoles such as Xbox or PlayStation, electronic book readers, and tablets such as iPads.[20]

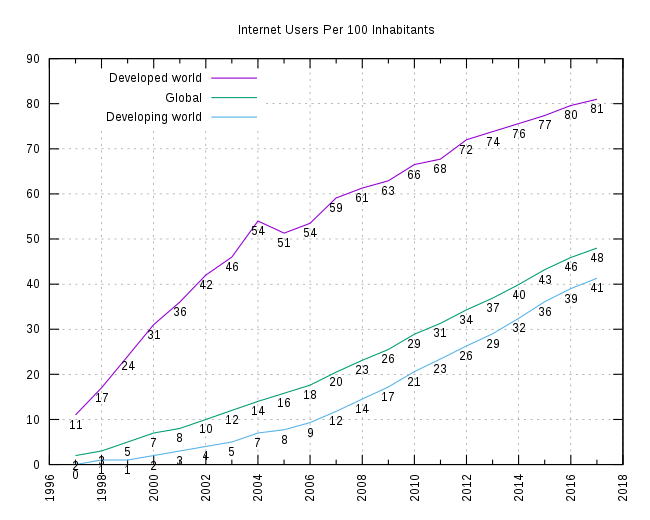

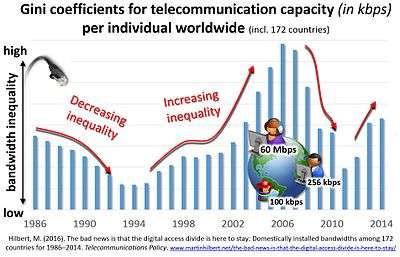

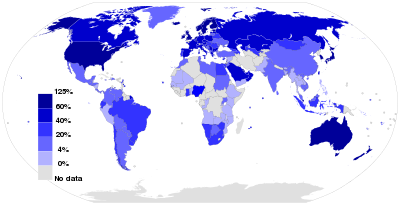

Traditionally the nature of the divide has been measured in terms of the existing numbers of subscriptions and digital devices. Given the increasing number of such devices, some have concluded that the digital divide among individuals has increasingly been closing as the result of a natural and almost automatic process.[2][22] Others point to persistent lower levels of connectivity among women, racial and ethnic minorities, people with lower incomes, rural residents, and less educated people as evidence that addressing inequalities in access to and use of the medium will require much more than the passing of time.[5][23] Recent studies have measured the digital divide not in terms of technological devices, but in terms of the existing bandwidth per individual (in kbit/s per capita).[4][21]

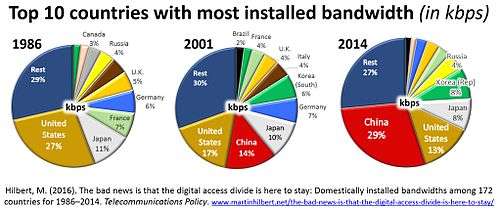

As shown in the Figure on the side, the digital divide in kbit/s is not monotonically decreasing but re-opens up with each new innovation. For example, "the massive diffusion of narrow-band Internet and mobile phones during the late 1990s" increased digital inequality, as well as "the initial introduction of broadband DSL and cable modems during 2003–2004 increased levels of inequality".[4] This is because a new kind of connectivity is never introduced instantaneously and uniformly to society as a whole at once, but diffuses slowly through social networks. As shown by the Figure, during the mid-2000s, communication capacity was more unequally distributed than during the late 1980s, when only fixed-line phones existed. The most recent increase in digital equality stems from the massive diffusion of the latest digital innovations (i.e. fixed and mobile broadband infrastructures, e.g. 3G and fiber optics FTTH).[24] Measurement methodologies of the digital divide, and more specifically an Integrated Iterative Approach General Framework (Integrated Contextual Iterative Approach – ICI) and the digital divide modeling theory under measurement model DDG (Digital Divide Gap) are used to analyze the gap existing between developed and developing countries, and the gap among the 27 members-states of the European Union.[25][26]

The bit as the unifying variable

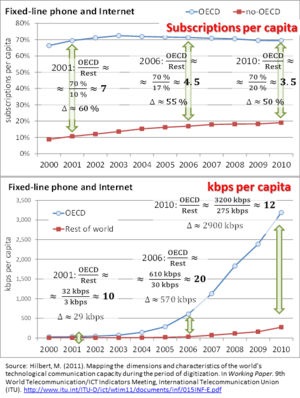

Instead of tracking various kinds of digital divides among fixed and mobile phones, narrow- and broadband Internet, digital TV, etc., it has recently been suggested to simply measure the amount of kbit/s per actor.[4][21][28][29] This approach has shown that the digital divide in kbit/s per capita is actually widening in relative terms: "While the average inhabitant of the developed world counted with some 40 kbit/s more than the average member of the information society in developing countries in 2001, this gap grew to over 3 Mbit/s per capita in 2010."[29]

The upper graph of the Figure on the side shows that the divide between developed and developing countries has been diminishing when measured in terms of subscriptions per capita. In 2001, fixed-line telecommunication penetration reached 70% of society in developed OECD countries and 10% of the developing world. This resulted in a ratio of 7 to 1 (divide in relative terms) or a difference of 60% (divide in absolute terms). During the next decade, fixed-line penetration stayed almost constant in OECD countries (at 70%), while the rest of the world started a catch-up, closing the divide to a ratio of 3.5 to 1. The lower graph shows the divide not in terms of ICT devices, but in terms of kbit/s per inhabitant. While the average member of developed countries counted with 29 kbit/s more than a person in developing countries in 2001, this difference got multiplied by a factor of one thousand (to a difference of 2900 kbit/s). In relative terms, the fixed-line capacity divide was even worse during the introduction of broadband Internet at the middle of the first decade of the 2000s, when the OECD counted with 20 times more capacity per capita than the rest of the world.[4] This shows the importance of measuring the divide in terms of kbit/s, and not merely to count devices. The International Telecommunications Union concludes that "the bit becomes a unifying variable enabling comparisons and aggregations across different kinds of communication technologies".[30]

Skills and digital literacy

However, research shows that the digital divide is more than just an access issue and cannot be alleviated merely by providing the necessary equipment. There are at least three factors at play: information accessibility, information utilization, and information receptiveness. More than just accessibility, individuals need to know how to make use of the information and communication tools once they exist within a community.[31] Information professionals have the ability to help bridge the gap by providing reference and information services to help individuals learn and utilize the technologies to which they do have access, regardless of the economic status of the individual seeking help.[32]

Gender digital divide

Due to the rapidly declining price of connectivity and hardware, skills deficits have eclipsed barriers of access as the primary contributor to the gender digital divide. Studies show that women are less likely to know how to leverage devices and internet access to their full potential, even when they do use digital technologies.[33] In rural India, for example, a study found that the majority of women who owned mobile phones only knew how to answer calls. They could not dial numbers or read messages without assistance from their husbands, due to a lack of literacy and numeracy skills.[34] Research conducted across 25 countries found that adolescent boys with mobile phones used them for a wider range of activities, from playing games to accessing financial services online, while adolescent girls tended to use just the basic functionalities such as making phone calls and using the calculator.[35] Similar trends can be seen even in areas where internet access is near-universal. A survey of women in nine cities around the world revealed that although 97% of women were using social media, only 48% of them were expanding their networks, and only 21% of internet-connected women had searched online for information related to health, legal rights or transport.[35] In some cities, less than one quarter of connected women had used the internet to look for a job.[33]

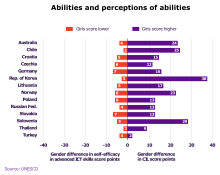

Studies show that despite strong performance in computer and information literacy (CIL), girls do not have confidence in their ICT abilities. According to the International Computer and Information Literacy Study (ICILS) assessment girls’ self-efficacy scores (their perceived as opposed to their actual abilities) for advanced ICT tasks were lower than boys’.[36][33]

Location

Internet connectivity can be utilized at a variety of locations such as homes, offices, schools, libraries, public spaces, Internet cafe and others. There are also varying levels of connectivity in rural, suburban, and urban areas.[37][38]

Applications

Common Sense Media, a nonprofit group based in San Francisco, surveyed almost 1,400 parents and reported in 2011 that 47 percent of families with incomes more than $75,000 had downloaded apps for their children, while only 14 percent of families earning less than $30,000 had done so.[39]

Reasons and correlating variables

The gap in a digital divide may exist for a number of reasons. Obtaining access to ICTs and using them actively has been linked to a number of demographic and socio-economic characteristics: among them income, education, race, gender, geographic location (urban-rural), age, skills, awareness, political, cultural and psychological attitudes.[40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47] Multiple regression analysis across countries has shown that income levels and educational attainment are identified as providing the most powerful explanatory variables for ICT access and usage.[48] Evidence was found that Caucasians are much more likely than non-Caucasians to own a computer as well as have access to the Internet in their homes. As for geographic location, people living in urban centers have more access and show more usage of computer services than those in rural areas. Gender was previously thought to provide an explanation for the digital divide, many thinking ICT were male gendered, but controlled statistical analysis has shown that income, education and employment act as confounding variables and that women with the same level of income, education and employment actually embrace ICT more than men (see Women and ICT4D).[49] However, each nation has its own set of causes or the digital divide. For example, the digital divide in Germany is unique because it is not largely due to difference in quality of infrastructure.[50]

One telling fact is that "as income rises so does Internet use ...", strongly suggesting that the digital divide persists at least in part due to income disparities.[51] Most commonly, a digital divide stems from poverty and the economic barriers that limit resources and prevent people from obtaining or otherwise using newer technologies.

In research, while each explanation is examined, others must be controlled in order to eliminate interaction effects or mediating variables,[40] but these explanations are meant to stand as general trends, not direct causes. Each component can be looked at from different angles, which leads to a myriad of ways to look at (or define) the digital divide. For example, measurements for the intensity of usages, such as incidence and frequency, vary by study. Some report usage as access to Internet and ICTs while others report usage as having previously connected to the Internet. Some studies focus on specific technologies, others on a combination (such as Infostate, proposed by Orbicom-UNESCO, the Digital Opportunity Index, or ITU's ICT Development Index). Based on different answers to the questions of who, with which kinds of characteristics, connects how and why to what there are hundreds of alternatives ways to define the digital divide.[10] "The new consensus recognizes that the key question is not how to connect people to a specific network through a specific device, but how to extend the expected gains from new ICTs." [52] In short, the desired impact and "the end justifies the definition" of the digital divide.[10]

Economic gap in the United States

During the mid-1990s, the US Department of Commerce, National Telecommunications & Information Administration (NTIA) began publishing reports about the Internet and access to and usage of the resource. The first of three reports is entitled "Falling Through the Net: A Survey of the ‘Have Nots’ in Rural and Urban America" (1995),[53] the second is "Falling Through the Net II: New Data on the Digital Divide" (1998),[54] and the final report "Falling Through the Net: Defining the Digital Divide" (1999).[55] The NTIA's final report attempted clearly to define the term digital divide; "the digital divide—the divide between those with access to new technologies and those without—is now one of America's leading economic and civil rights issues. This report will help clarify which Americans are falling further behind so that we can take concrete steps to redress this gap."[55] Since the introduction of the NTIA reports, much of the early, relevant literature began to reference the NTIA's digital divide definition. The digital divide is commonly defined as being between the "haves" and "have-nots."[55][56] The economic gap really comes into play when referring to the older generations.

Racial gap

Although many groups in society are affected by a lack of access to computers or the internet, communities of color are specifically observed to be negatively affected by the digital divide. This is evident when it comes to observing home-internet access among different races and ethnicities. 81% of Whites and 83% of Asians have home internet access, compared to 70% of Hispanics, 68% of Blacks, 72% of American Indian/Alaska Natives, and 68% of Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders. Although income is a factor in home-internet access disparities, there are still racial and ethnic inequalities that are present among those within lower income groups. 58% of low income Whites are reported to have home-internet access in comparison to 51% of Hispanics and 50% of Blacks. This information is reported in a report titled “Digital Denied: The Impact of Systemic Racial Discrimination on Home-Internet Adoption” which was published by the DC-based public interest group Fress Press. The report concludes that structural barriers and discrimination that perpetuates bias against people of different races and ethnicities contribute to having an impact on the digital divide. The report also concludes that those who do not have internet access still have a high demand for it, and reduction in the price of home-internet access would allow for an increase in equitable participation and improve internet adoption by marginalized groups.[57]

Digital censorship and algorithmic bias are observed to be present in the racial divide. Hate-speech rules as well as hate speech algorithms online platforms such as Facebook have favored white males and those belonging to elite groups in society over marginalized groups in society, such as women and people of color. In a collection of internal documents that were collected in a project conducted by ProPublica, Facebook's guidelines in regards to distinguishing hate speech and recognizing protected groups revealed slides that identified three groups, each one containing either female drivers, black children, or white men. When the question of which subset group is protected is presented, the correct answer was white men . Minority group language is negatively impacted by automated tools of hate detection due to human bias that ultimately decides what is considered hate speech and what is not.

Online platforms have also been observed to tolerate hateful content towards people of color but restrict content from people of color. Aboriginal memes on a Facebook page were posted with racially abusive content and comments depicting Aboriginal people as inferior. While the contents on the page were removed by the originators after an investigation conducted by the Australian Communications and Media Authority, Facebook did not delete the page and has allowed it to remain under the classification of controversial humor . However, a post by an African American woman addressing her uncomfortableness of being the only person of color in a small-town restaurant was met with racist and hateful messages. When reporting the online abuse to Facebook, her account was suspended by Facebook for three days for posting the screenshots while those responsible for the racist comments she received were not suspended. Shared experiences between people of color can be at risk of being silenced under removal policies for online platforms.

Disability gap

Inequities in access to information technologies are present among individuals living with a disability in comparison to those who are not living with a disability. According to The Pew Research Center, 54% of households with a person who has a disability have home internet access compared to 81% of households that have home internet access and do not have a person who has a disability.[58] The type of disability an individual has can prevent one from interacting with computer screens and smartphone screens, such as having a quadriplegia disability or having a disability in the hands. However, there is still a lack of access to technology and home internet access among those who have a cognitive and auditory disability as well. There is a concern of whether or not the increase in the use of information technologies will increase equality through offering opportunities for individuals living with disabilities or whether it will only add to the present inequalities and lead to individuals living with disabilities being left behind in society. Issues such as the perception of disabilities in society, Federal and state government policy, corporate policy, mainstream computing technologies, and real-time online communication have been found to contribute to the impact of the digital divide on individuals with disabilities .

People with disabilities are also the targets of online abuse. Online disability hate crimes have increased by 33% across the UK between 2016–17 and 2017-18 according to a report published by Leonard Cheshire, a health and welfare charity.[59] Accounts of online hate abuse towards people with disabilities were shared during an incident in 2019 when model Katie Price's son was the target of online abuse that was attributed to him having a disability. In response to the abuse, a campaign was launched by Katie Price to ensure that Britain's MP's held those who are guilty of perpetuating online abuse towards those with disabilities accountable.[60] Online abuse towards individuals with disabilities is a factor that can discourage people from engaging online which could prevent people from learning information that could improve their lives. Many individuals living with disabilities face online abuse in the form of accusations of benefit fraud and “faking” their disability for financial gain, which in some cases leads to unnecessary investigations.

Gender gap

A paper published by J. Cooper from Princeton University points out that learning technology is designed to be receptive to men instead of women. The reasoning for this is that most software engineers and programmers are men, and they communicate their learning software in a way that would match the reception of their recipient. The association of computers in education is normally correlated with the male gender, and this has an impact on the education of computers and technology among women, although it is important to mention that there are plenty of learning software that are designed to help women and girls learn technology. Overall, the study presents the problem of various perspectives in society that are a result of gendered socialization patterns that believe that computers are a part of the male experience since computers have traditionally presented as a toy for boys when they are children.[61] This divide is followed as children grow older and young girls are not encouraged as much to pursue degrees in IT and computer science. In 1990, the percentage of women in computing jobs was 36%, however in 2016, this number had fallen to 25%. This can be seen in the underrepresentation of women in IT hubs such as Silicon Valley.[62]

There has also been the presence of algorithmic bias that has been shown in machine learning algorithms that are implemented by major companies. In 2015, Amazon had to abandon a recruiting algorithm that showed a difference between ratings that candidates received for software developer jobs as well as other technical jobs. As a result, it was revealed that Amazon's machine algorithm was biased against women and favored male resumes over female resumes. This was due to the fact that Amazon's computer models were trained to vet patterns in resumes over a 10-year period. During this ten-year period, the majority of the resumes belong to male individuals, which is a reflection of male dominance across the tech industry.[63]

LGBT gap

A number of states, including some that have introduced new laws since 2010, notably censor voices from and content related to the LGBT community, posing serious consequences to access to information about sexual orientation and gender identity. Digital platforms play a powerful role in limiting access to certain content, such as YouTube's 2017 decision to classify non-explicit videos with LGBT themes as ‘restricted’, a classification designed to filter out ‘potentially inappropriate content’.[64] The internet provides information that can create a safe space for marginalized groups such as the LGBT community to connect with others and engage in honest dialogues and conversations that are affecting their communities. It can also be viewed as an agent of change for the LGBT community and provide a means of engaging in social justice. It can allow for LGBT individuals who may be living in rural areas or in areas where they are isolated to gain access to information that are not within their rural system as well as gaining information from other LGBT individuals. This includes information such as healthcare, partners, and news. GayHealth provides online medical and health information and Gay and Lesbians Alliance Against Defamation contains online publications and news that focus on human rights campaigns and issues focused on LGBT issues. The Internet also allows LGBT individuals to maintain anonymity. Lack of access to the internet can hinder these things, due to lack of broadband access in remote rural areas. LGBT Tech has emphasized launching newer technologies with 5G technology in order to help close the digital divide that can cause members of the LGBT community to lose access to reliable and fast technology that can provide information on healthcare, economic opportunities, and safe communities.[65]

Age gap

Older adults, those ages 60 and up, face various barriers that contribute to their lack of access to information and communication technologies (ICTs). Many adults are “digital immigrants” who have not had lifelong exposure to digital media and have had to adapt to incorporating it in their lives.[66] A study in 2005 found that only 26% of people aged 65 and over were Internet users, compared to 67% in the 50-64 age group and 80% in the 30-49 year age group.[67] This "grey divide" can be due to factors such as concern over security, motivation and self-efficacy, decline of memory or spatial orientation, cost, or lack of support.[68] The aforementioned variables of race, disability, gender, and sexual orientation also add to the barriers for older adults.

Many older adults may have physical or mental disabilities that render them homebound and financially insecure. They may be unable to afford internet access or lack transportation to use computers in public spaces, the benefits of which would be enhancing their health and reducing their social isolation and depression. Homebound older adults would benefit from internet use by using it to access health information, use telehealth resources, shop and bank online, and stay connected with friends or family using email or social networks.[69]

Those in more privileged socio-economic positions and with a higher level of education are more likely to have internet access than those older adults living in poverty. Lack of access to the internet inhibits "capital-enhancing activities" such as accessing government assistance, job opportunities, or investments. The results of the U.S. Federal Communication Commission's 2009 National Consumer Broadband Service Capability Survey shows that older women are less likely to use the internet, especially for capital enhancing activities, than their male counterparts.[70]

Facebook divide

The Facebook divide,[71][72][73][74] a concept derived from the "digital divide", is the phenomenon with regard to access to, use of, or impact of Facebook on individual society and among societies. It is suggested at the International Conference on Management Practices for the New Economy (ICMAPRANE-17) on February 10–11, 2017.[75] Additional concepts of Facebook Native and Facebook Immigrants are suggested at the conference. The Facebook Divide, Facebook native, Facebook immigrants, and Facebook left-behind are concepts for social and business management research. Facebook Immigrants are utilizing Facebook for their accumulation of both bonding and bridging social capital. These Facebook Native, Facebook Immigrants, and Facebook left-behind induced the situation of Facebook inequality. In February 2018, the Facebook Divide Index was introduced at the ICMAPRANE[76] conference in Noida, India, to illustrate the Facebook Divide phenomenon.

Overcoming the divide

An individual must be able to connect in order to achieve enhancement of social and cultural capital as well as achieve mass economic gains in productivity. Therefore, access is a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for overcoming the digital divide. Access to ICT meets significant challenges that stem from income restrictions. The borderline between ICT as a necessity good and ICT as a luxury good is roughly around the "magical number" of US$10 per person per month, or US$120 per year,[48] which means that people consider ICT expenditure of US$120 per year as a basic necessity. Since more than 40% of the world population lives on less than US$2 per day, and around 20% live on less than US$1 per day (or less than US$365 per year), these income segments would have to spend one third of their income on ICT (120/365 = 33%). The global average of ICT spending is at a mere 3% of income.[48] Potential solutions include driving down the costs of ICT, which includes low-cost technologies and shared access through Telecentres.

Furthermore, even though individuals might be capable of accessing the Internet, many are thwarted by barriers to entry, such as a lack of means to infrastructure or the inability to comprehend the information that the Internet provides. Lack of adequate infrastructure and lack of knowledge are two major obstacles that impede mass connectivity. These barriers limit individuals' capabilities in what they can do and what they can achieve in accessing technology. Some individuals can connect, but they do not have the knowledge to use what information ICTs and Internet technologies provide them. This leads to a focus on capabilities and skills, as well as awareness to move from mere access to effective usage of ICT.[6]

The United Nations is aiming to raise awareness of the divide by way of the World Information Society Day which has taken place yearly since May 17, 2006.[77] It also set up the Information and Communications Technology (ICT) Task Force in November 2001.[78] Later UN initiatives in this area are the World Summit on the Information Society, which was set up in 2003, and the Internet Governance Forum, set up in 2006.

In the year 2000, the United Nations Volunteers (UNV) programme launched its Online Volunteering service,[79] which uses ICT as a vehicle for and in support of volunteering. It constitutes an example of a volunteering initiative that effectively contributes to bridge the digital divide. ICT-enabled volunteering has a clear added value for development. If more people collaborate online with more development institutions and initiatives, this will imply an increase in person-hours dedicated to development cooperation at essentially no additional cost. This is the most visible effect of online volunteering for human development.[80]

Social media websites serve as both manifestations of and means by which to combat the digital divide. The former describes phenomena such as the divided users' demographics that make up sites such as Facebook and Myspace or Word Press and Tumblr. Each of these sites hosts thriving communities that engage with otherwise marginalized populations. An example of this is the large online community devoted to Afrofuturism, a discourse that critiques dominant structures of power by merging themes of science fiction and blackness. Social media brings together minds that may not otherwise meet, allowing for the free exchange of ideas and empowerment of marginalized discourses.

Libraries

.jpg)

Attempts to bridge the digital divide include a program developed in Durban, South Africa, where deficient access to technology and a lack of documented cultural heritage has motivated the creation of an "online indigenous digital library as part of public library services."[81] This project has the potential to narrow the digital divide by not only giving the people of the Durban area access to this digital resource, but also by incorporating the community members into the process of creating it.

To address the divide The Gates Foundation started the Gates Library Initiative which provides training assistance and guidance in libraries.[7]

In nations where poverty compounds effects of the digital divide, programs are emerging to counter those trends. In Kenya, lack of funding, language, and technology illiteracy contributed to an overall lack of computer skills and educational advancement. This slowly began to change when foreign investment began. In the early 2000s, the Carnegie Foundation funded a revitalization project through the Kenya National Library Service. Those resources enabled public libraries to provide information and communication technologies to their patrons. In 2012, public libraries in the Busia and Kiberia communities introduced technology resources to supplement curriculum for primary schools. By 2013, the program expanded into ten schools.[82]

Effective use

Community Informatics (CI) provides a somewhat different approach to addressing the digital divide by focusing on issues of "use" rather than simply "access". CI is concerned with ensuring the opportunity not only for ICT access at the community level but also, according to Michael Gurstein, that the means for the "effective use" of ICTs for community betterment and empowerment are available.[83] Gurstein has also extended the discussion of the digital divide to include issues around access to and the use of "open data" and coined the term "data divide" to refer to this issue area.[84]

Implications

Social capital

Once an individual is connected, Internet connectivity and ICTs can enhance his or her future social and cultural capital. Social capital is acquired through repeated interactions with other individuals or groups of individuals. Connecting to the Internet creates another set of means by which to achieve repeated interactions. ICTs and Internet connectivity enable repeated interactions through access to social networks, chat rooms, and gaming sites. Once an individual has access to connectivity, obtains infrastructure by which to connect, and can understand and use the information that ICTs and connectivity provide, that individual is capable of becoming a "digital citizen." [40]

Economic disparity

In the United States, the research provided by Sungard Availability Services notes a direct correlation between a company's access to technological advancements and its overall success in bolstering the economy.[85] The study, which includes over 2,000 IT executives and staff officers, indicates that 69 percent of employees feel they do not have access to sufficient technology in order to make their jobs easier, while 63 percent of them believe the lack of technological mechanisms hinders their ability to develop new work skills.[85] Additional analysis provides more evidence to show how the digital divide also affects the economy in places all over the world. A BCG report suggests that in countries like Sweden, Switzerland, and the U.K., the digital connection among communities is made easier, allowing for their populations to obtain a much larger share of the economies via digital business.[86] In fact, in these places, populations hold shares approximately 2.5 percentage points higher.[86] During a meeting with the United Nations a Bangladesh representative expressed his concern that poor and undeveloped countries would be left behind due to a lack of funds to bridge the digital gap.[87]

Education

The digital divide also impacts children's ability to learn and grow in low-income school districts. Without Internet access, students are unable to cultivate necessary tech skills in order to understand today's dynamic economy.[88] Federal Communication Commission's Broadband Task Force created a report showing that about 70% of teachers give students homework that demand access to broadband.[89] Even more, approximately 65% of young scholars use the Internet at home to complete assignments as well as connect with teachers and other students via discussion boards and shared files.[89] A recent study indicates that practically 50% of students say that they are unable to finish their homework due to an inability to either connect to the Internet or in some cases, find a computer.[89] This has led to a new revelation: 42% of students say they received a lower grade because of this disadvantage.[89] Finally, according to research conducted by the Center for American Progress, "if the United States were able to close the educational achievement gaps between native-born white children and black and Hispanic children, the U.S. economy would be 5.8 percent—or nearly $2.3 trillion—larger in 2050".[90]

In a reverse of this idea, well-off families, especially the tech-savvy parents in Silicon Valley, carefully limit their own children's screen time. The children of wealthy families attend play-based preschool programs that emphasize social interaction instead of time spent in front of computers or other digital devices, and they pay to send their children to schools that limit screen time.[17] American families that cannot afford high-quality childcare options are more likely to use tablet computers filled with apps for children as a cheap replacement for a babysitter, and their government-run schools encourage screen time during school.[17]

Demographic differences

Furthermore, according to the 2012 Pew Report "Digital Differences," a mere 62% of households who make less than $30,000 a year use the Internet, while 90% of those making between $50,000 and $75,000 had access.[88] Studies also show that only 51% of Hispanics and 49% of African Americans have high-speed Internet at home. This is compared to the 66% of Caucasians that too have high-speed Internet in their households.[88] Overall, 10% of all Americans do not have access to high-speed Internet, an equivalent of almost 34 million people.[91] Supplemented reports from the Guardian demonstrate the global effects of limiting technological developments in poorer nations, rather than simply the effects in the United States. Their study shows that rapid digital expansion excludes those who find themselves in the lower class. 60% of the world's population, almost 4 billion people, have no access to the Internet and are thus left worse off.[92]

Criticisms

Knowledge divide

Since gender, age, racial, income, and educational digital divides have lessened compared to the past, some researchers suggest that the digital divide is shifting from a gap in access and connectivity to ICTs to a knowledge divide.[93] A knowledge divide concerning technology presents the possibility that the gap has moved beyond the access and having the resources to connect to ICTs to interpreting and understanding information presented once connected.[94]

Second-level digital divide

The second-level digital divide also referred to as the production gap, describes the gap that separates the consumers of content on the Internet from the producers of content.[95] As the technological digital divide is decreasing between those with access to the Internet and those without, the meaning of the term digital divide is evolving.[93] Previously, digital divide research has focused on accessibility to the Internet and Internet consumption. However, with more and more of the population gaining access to the Internet, researchers are examining how people use the Internet to create content and what impact socioeconomics are having on user behavior.[8][96] New applications have made it possible for anyone with a computer and an Internet connection to be a creator of content, yet the majority of user-generated content available widely on the Internet, like public blogs, is created by a small portion of the Internet-using population. Web 2.0 technologies like Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and Blogs enable users to participate online and create content without having to understand how the technology actually works, leading to an ever-increasing digital divide between those who have the skills and understanding to interact more fully with the technology and those who are passive consumers of it.[95] Many are only nominal content creators through the use of Web 2.0, posting photos and status updates on Facebook, but not truly interacting with the technology.

Some of the reasons for this production gap include material factors like the type of Internet connection one has and the frequency of access to the Internet. The more frequently a person has access to the Internet and the faster the connection, the more opportunities they have to gain the technology skills and the more time they have to be creative.[97]

Other reasons include cultural factors often associated with class and socioeconomic status. Users of lower socioeconomic status are less likely to participate in content creation due to disadvantages in education and lack of the necessary free time for the work involved in blog or web site creation and maintenance.[97] Additionally, there is evidence to support the existence of the second-level digital divide at the K-12 level based on how educators' use technology for instruction.[98] Schools' economic factors have been found to explain variation in how teachers use technology to promote higher-order thinking skills.[98]

The global digital divide

| 2005 | 2010 | 2017 | 2019a | |

| World population[101] | 6.5 billion | 6.9 billion | 7.4 billion | 7.75 billion |

| Users worldwide | 16% | 30% | 48% | 53.6% |

| Users in the developing world | 8% | 21% | 41.3% | 47% |

| Users in the developed world | 51% | 67% | 81% | 86.6% |

| a Estimate. Source: International Telecommunications Union.[102] | ||||

| 2005 | 2010 | 2017 | 2019a | |

| Africa | 2% | 10% | 21.8% | 28.2% |

| Americas | 36% | 49% | 65.9% | 77.2% |

| Arab States | 8% | 26% | 43.7% | 51.6% |

| Asia and Pacific | 9% | 23% | 43.9% | 48.4% |

| Commonwealth of Independent States |

10% |

34% |

67.7% |

72.2% |

| Europe | 46% | 67% | 79.6% | 82.5% |

| a Estimate. Source: International Telecommunication Union.[103] | ||||

as a percentage of a country's population

| 2007 | 2010 | 2016 | 2019a | |

| World population[105] | 6.6 billion | 6.9 billion | 7.3 billion | 7.75 billion |

| Fixed broadband | 5% | 8% | 11.9% | 14.5% |

| Developing world | 2% | 4% | 8.2% | 11.2% |

| Developed world | 18% | 24% | 30.1% | 33.6% |

| Mobile broadband | 4% | 11% | 49.4% | 83% |

| Developing world | 1% | 4% | 40.9% | 75.2% |

| Developed world | 19% | 43% | 90.3% | 121.7% |

| a Estimate. Source: International Telecommunication Union.[106] | ||||

| Fixed subscriptions: | 2007 | 2010 | 2014 | 2019a |

| Africa | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.4% |

| Americas | 11% | 14% | 17% | 22% |

| Arab States | 1% | 2% | 3% | 8.1% |

| Asia and Pacific | 3% | 6% | 8% | 14.4% |

| Commonwealth of Independent States |

2% |

8% |

14% |

19.8% |

| Europe | 18% | 24% | 28% | 31.9% |

| Mobile subscriptions: | 2007 | 2010 | 2014 | 2019a |

| Africa | 0.2% | 2% | 19% | 34% |

| Americas | 6% | 23% | 59% | 104.4% |

| Arab States | 0.8% | 5% | 25% | 67.3% |

| Asia and Pacific | 3% | 7% | 23% | 89% |

| Commonwealth of Independent States |

0.2% |

22% |

49% |

85.4% |

| Europe | 15% | 29% | 64% | 97.4% |

| a Estimate. Source: International Telecommunications Union.[103] | ||||

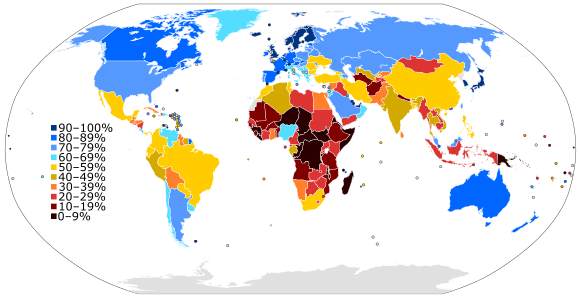

The global digital divide describes global disparities, primarily between developed and developing countries, in regards to access to computing and information resources such as the Internet and the opportunities derived from such access.[107] As with a smaller unit of analysis, this gap describes an inequality that exists, referencing a global scale.

The Internet is expanding very quickly, and not all countries—especially developing countries—can keep up with the constant changes. The term "digital divide" does not necessarily mean that someone does not have technology; it could mean that there is simply a difference in technology. These differences can refer to, for example, high-quality computers, fast Internet, technical assistance, or telephone services. The difference between all of these is also considered a gap.

There is a large inequality worldwide in terms of the distribution of installed telecommunication bandwidth. In 2014 only three countries (China, US, Japan) host 50% of the globally installed bandwidth potential (see pie-chart Figure on the right).[21] This concentration is not new, as historically only ten countries have hosted 70–75% of the global telecommunication capacity (see Figure). The U.S. lost its global leadership in terms of installed bandwidth in 2011, being replaced by China, which hosts more than twice as much national bandwidth potential in 2014 (29% versus 13% of the global total).[21]

Versus the digital divide

The global digital divide is a special case of the digital divide; the focus is set on the fact that "Internet has developed unevenly throughout the world"[44]:681 causing some countries to fall behind in technology, education, labor, democracy, and tourism. The concept of the digital divide was originally popularized regarding the disparity in Internet access between rural and urban areas of the United States of America; the global digital divide mirrors this disparity on an international scale.

The global digital divide also contributes to the inequality of access to goods and services available through technology. Computers and the Internet provide users with improved education, which can lead to higher wages; the people living in nations with limited access are therefore disadvantaged.[108] This global divide is often characterized as falling along what is sometimes called the North–South divide of "northern" wealthier nations and "southern" poorer ones.

Obstacles to a solution

Some people argue that necessities need to be considered before achieving digital inclusion, such as an ample food supply and quality health care. Minimizing the global digital divide requires considering and addressing the following types of access:

Physical access

Involves "the distribution of ICT devices per capita…and land lines per thousands".[45]:306 Individuals need to obtain access to computers, landlines, and networks in order to access the Internet. This access barrier is also addressed in Article 21 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities by the United Nations.

Financial access

The cost of ICT devices, traffic, applications, technician and educator training, software, maintenance, and infrastructures require ongoing financial means.[48] Financial access and "the levels of household income play a significant role in widening the gap" [109]

Socio-demographic access

Empirical tests have identified that several socio-demographic characteristics foster or limit ICT access and usage. Among different countries, educational levels and income are the most powerful explanatory variables, with age being a third one.[10][48]

While a Global Gender Gap in access and usage of ICT's exist, empirical evidence shows that this is due to unfavorable conditions concerning employment, education and income and not to technophobia or lower ability. In the contexts understudy, women with the prerequisites for access and usage turned out to be more active users of digital tools than men.[49] In the US, for example, the figures for 2018 show 89% of men and 88% of women use the Internet.[110]

Cognitive access

In order to use computer technology, a certain level of information literacy is needed. Further challenges include information overload and the ability to find and use reliable information.

Design access

Computers need to be accessible to individuals with different learning and physical abilities including complying with Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act as amended by the Workforce Investment Act of 1998 in the United States.[111]

Institutional access

In illustrating institutional access, Wilson states "the numbers of users are greatly affected by whether access is offered only through individual homes or whether it is offered through schools, community centers, religious institutions, cybercafés, or post offices, especially in poor countries where computer access at work or home is highly limited".[45]:303

Political access

Guillen & Suarez argue that "democratic political regimes enable faster growth of the Internet than authoritarian or totalitarian regimes." [44]:687 The Internet is considered a form of e-democracy, and attempting to control what citizens can or cannot view is in contradiction to this. Recently situations in Iran and China have denied people the ability to access certain websites and disseminate information. Iran has prohibited the use of high-speed Internet in the country and has removed many satellite dishes in order to prevent the influence of Western culture, such as music and television.[112]

Cultural access

Many experts claim that bridging the digital divide is not sufficient and that the images and language needed to be conveyed in a language and images that can be read across different cultural lines.[46] A 2013 study conducted by Pew Research Center noted how participants taking the survey in Spanish were nearly twice as likely not to use the internet.[113]

Examples

In the early 21st century, residents of developed countries enjoy many Internet services which are not yet widely available in developing countries, including:

- In tandem with the above point, mobile phones, and small electronic communication devices;

- E-communities and social-networking;

- Fast broadband Internet connections, enabling advanced Internet applications;[114]

- Affordable and widespread Internet access, either through personal computers at home or work, through public terminals in public libraries and Internet cafes, and through wireless access points;

- E-commerce enabled by efficient electronic payment networks like credit cards and reliable shipping services;

- Virtual globes featuring street maps searchable down to individual street addresses and detailed satellite and aerial photography;

- Online research systems like LexisNexis and ProQuest which enable users to peruse newspaper and magazine articles that may be centuries old, without having to leave home;

- Electronic readers such as Kindle, Sony Reader, Samsung Papyrus and Iliad by iRex Technologies;

- Price engines like Google Shopping which help consumers find the best possible online prices and similar services like ShopLocal which find the best possible prices at local retailers;

- Electronic services delivery of government services, such as the ability to pay taxes, fees, and fines online.

- Further civic engagement through e-government and other sources such as finding information about candidates regarding political situations.

Global solutions

There are four specific arguments why it is important to "bridge the gap":[115]

- Economic equality – For example, the telephone is often seen as one of the most important components, because having access to a working telephone can lead to higher safety. If there were to be an emergency, one could easily call for help if one could use a nearby phone. In another example, many work-related tasks are online, and people without access to the Internet may not be able to complete work up to company standards. The Internet is regarded by some as a basic component of civic life that developed countries ought to guarantee for their citizens. Additionally, welfare services, for example, are sometimes offered via the Internet.[115]

- Social mobility – Computer and Internet use is regarded as being very important to development and success. However, some children are not getting as much technical education as others, because lower socioeconomic areas cannot afford to provide schools with computer facilities. For this reason, some kids are being separated and not receiving the same chance as others to be successful.[115]

- Democracy – Some people believe that eliminating the digital divide would help countries become healthier democracies. They argue that communities would become much more involved in events such as elections or decision making.[116][115]

- Economic growth – It is believed that less-developed nations could gain quick access to economic growth if the information infrastructure were to be developed and well used. By improving the latest technologies, certain countries and industries can gain a competitive advantage.[115]

While these four arguments are meant to lead to a solution to the digital divide, there are a couple of other components that need to be considered. The first one is rural living versus suburban living. Rural areas used to have very minimal access to the Internet, for example. However, nowadays, power lines and satellites are used to increase the availability in these areas. Another component to keep in mind is disabilities. Some people may have the highest quality technologies, but a disability they have may keep them from using these technologies to their fullest extent.[115]

Using previous studies (Gamos, 2003; Nsengiyuma & Stork, 2005; Harwit, 2004 as cited in James), James asserts that in developing countries, "internet use has taken place overwhelmingly among the upper-income, educated, and urban segments" largely due to the high literacy rates of this sector of the population.[117]:58 As such, James suggests that part of the solution requires that developing countries first build up the literacy/language skills, computer literacy, and technical competence that low-income and rural populations need in order to make use of ICT.

It has also been suggested that there is a correlation between democrat regimes and the growth of the Internet. One hypothesis by Gullen is, "The more democratic the polity, the greater the Internet use...The government can try to control the Internet by monopolizing control" and Norris et al. also contends, "If there is less government control of it, the Internet flourishes, and it is associated with greater democracy and civil liberties.[118]

From an economic perspective, Pick and Azari state that "in developing nations…foreign direct investment (FDI), primary education, educational investment, access to education, and government prioritization of ICT as all-important".[118]:112 Specific solutions proposed by the study include: "invest in stimulating, attracting, and growing creative technical and scientific workforce; increase the access to education and digital literacy; reduce the gender divide and empower women to participate in the ICT workforce; emphasize investing in intensive Research and Development for selected metropolitan areas and regions within nations".[118]:111

There are projects worldwide that have implemented, to various degrees, the solutions outlined above. Many such projects have taken the form of Information Communications Technology Centers (ICT centers). Rahnman explains that "the main role of ICT intermediaries is defined as an organization providing effective support to local communities in the use and adaptation of technology. Most commonly, an ICT intermediary will be a specialized organization from outside the community, such as a non-governmental organization, local government, or international donor. On the other hand, a social intermediary is defined as a local institution from within the community, such as a community-based organization.[119]:128

Other proposed solutions that the Internet promises for developing countries are the provision of efficient communications within and among developing countries so that citizens worldwide can effectively help each other to solve their problems. Grameen Banks and Kiva loans are two microcredit systems designed to help citizens worldwide to contribute online towards entrepreneurship in developing communities. Economic opportunities range from entrepreneurs who can afford the hardware and broadband access required to maintain Internet cafés to agribusinesses having control over the seeds they plant.

At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the IMARA organization (from Swahili word for "power") sponsors a variety of outreach programs which bridge the Global Digital Divide. Its aim is to find and implement long-term, sustainable solutions which will increase the availability of educational technology and resources to domestic and international communities. These projects are run under the aegis of the MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) and staffed by MIT volunteers who give training, install and donate computer setups in greater Boston, Massachusetts, Kenya, Indian reservations the American Southwest such as the Navajo Nation, the Middle East, and Fiji Islands. The CommuniTech project strives to empower underserved communities through sustainable technology and education.[120][121][122] According to Dominik Hartmann of the MIT's Media Lab, interdisciplinary approaches are needed to bridge the global digital divide.[123]

Building on the premise that any effective solution must be decentralized, allowing the local communities in developing nations to generate their content, one scholar has posited that social media—like Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter—may be useful tools in closing the divide.[124] As Amir Hatem Ali suggests, "the popularity and generative nature of social media empower individuals to combat some of the main obstacles to bridging the digital divide".[124]:188 Facebook's statistics reinforce this claim. According to Facebook, more than seventy-five percent of its users reside outside of the US.[125] Moreover, more than seventy languages are presented on its website.[125] The reasons for the high number of international users are due to many the qualities of Facebook and other social media. Amongst them, are its ability to offer a means of interacting with others, user-friendly features, and the fact that most sites are available at no cost.[124] The problem with social media, however, is that it can be accessible, provided that there is physical access.[124] Nevertheless, with its ability to encourage digital inclusion, social media can be used as a tool to bridge the global digital divide.[124]

Some cities in the world have started programs to bridge the digital divide for their residents, school children, students, parents and the elderly. One such program, founded in 1996, was sponsored by the city of Boston and called the Boston Digital Bridge Foundation.[126] It especially concentrates on school children and their parents, helping to make both equally and similarly knowledgeable about computers, using application programs, and navigating the Internet.[127][128]

Free Basics

Free Basics is a partnership between social networking services company Facebook and six companies (Samsung, Ericsson, MediaTek, Opera Software, Nokia and Qualcomm) that plans to bring affordable access to selected Internet services to less developed countries by increasing efficiency, and facilitating the development of new business models around the provision of Internet access. In the whitepaper[129] realised by Facebook's founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg, connectivity is asserted as a "human right", and Internet.org is created to improve Internet access for people around the world.

"Free Basics provides people with access to useful services on their mobile phones in markets where internet access may be less affordable. The websites are available for free without data charges, and include content about news, employment, health, education and local information etc. By introducing people to the benefits of the internet through these websites, we hope to bring more people online and help improve their lives."[130]

However, Free Basics is also accused of violating net neutrality for limiting access to handpicked services. Despite a wide deployment in numerous countries, it has been met with heavy resistance notably in India where the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India eventually banned it in 2016.

Satellite constellations

Several projects to bring internet to the entire world with a satellite constellation have been devised in the last decade, one of these being Starlink by Elon Musk's company SpaceX. Unlike Free Basics, it would provide people with a full internet access and would not be limited to a few selected services. In the same week Starlink was announced, serial-entrepreneur Richard Branson announced his own project OneWeb, a similar constellation with approximately 700 satellites that was already procured communication frequency licenses for their broadcast spectrum and could possibly be operational on 2020.[131]

The biggest hurdle to these projects is the astronomical, financial, and logistical cost of launching so many satellites. After the failure of previous satellite-to-consumer space ventures, satellite industry consultant Roger Rusch said "It's highly unlikely that you can make a successful business out of this." Musk has publicly acknowledged this business reality, and indicated in mid-2015 that while endeavoring to develop this technically-complicated space-based communication system he wants to avoid overextending the company and stated that they are being measured in the pace of development.

One Laptop per Child

One Laptop per Child (OLPC) is another attempt to narrow the digital divide.[132] This organization, founded in 2005, provides inexpensively produced "XO" laptops (dubbed the "$100 laptop", though actual production costs vary) to children residing in poor and isolated regions within developing countries. Each laptop belongs to an individual child and provides a gateway to digital learning and Internet access. The XO laptops are designed to withstand more abuse than higher-end machines, and they contain features in context to the unique conditions that remote villages present. Each laptop is constructed to use as little power as possible, have a sunlight-readable screen, and is capable of automatically networking with other XO laptops in order to access the Internet—as many as 500 machines can share a single point of access.[132]

World Summit on the Information Society

Several of the 67 principles adopted at the World Summit on the Information Society convened by the United Nations in Geneva in 2003 directly address the digital divide:[133]

- 10. We are also fully aware that the benefits of the information technology revolution are today unevenly distributed between the developed and developing countries and within societies. We are fully committed to turning this digital divide into a digital opportunity for all, particularly for those who risk being left behind and being further marginalized.

- 11. We are committed to realizing our common vision of the Information Society for ourselves and for future generations. We recognize that young people are the future workforce and leading creators and earliest adopters of ICTs. They must therefore be empowered as learners, developers, contributors, entrepreneurs and decision-makers. We must focus especially on young people who have not yet been able to benefit fully from the opportunities provided by ICTs. We are also committed to ensuring that the development of ICT applications and operation of services respects the rights of children as well as their protection and well-being.

- 12. We affirm that development of ICTs provides enormous opportunities for women, who should be an integral part of, and key actors, in the Information Society. We are committed to ensuring that the Information Society enables women's empowerment and their full participation on the basis on equality in all spheres of society and in all decision-making processes. To this end, we should mainstream a gender equality perspective and use ICTs as a tool to that end.

- 13. In building the Information Society, we shall pay particular attention to the special needs of marginalized and vulnerable groups of society, including migrants, internally displaced persons and refugees, unemployed and underprivileged people, minorities and nomadic people. We shall also recognize the special needs of older persons and persons with disabilities.

- 14. We are resolute to empower the poor, particularly those living in remote, rural and marginalized urban areas, to access information and to use ICTs as a tool to support their efforts to lift themselves out of poverty.

- 15. In the evolution of the Information Society, particular attention must be given to the special situation of indigenous peoples, as well as to the preservation of their heritage and their cultural legacy.

- 16. We continue to pay special attention to the particular needs of people of developing countries, countries with economies in transition, Least Developed Countries, Small Island Developing States, Landlocked Developing Countries, Highly Indebted Poor Countries, countries and territories under occupation, countries recovering from conflict and countries and regions with special needs as well as to conditions that pose severe threats to development, such as natural disasters.

- 21. Connectivity is a central enabling agent in building the Information Society. Universal, ubiquitous, equitable and affordable access to ICT infrastructure and services, constitutes one of the challenges of the Information Society and should be an objective of all stakeholders involved in building it. Connectivity also involves access to energy and postal services, which should be assured in conformity with the domestic legislation of each country.

- 28. We strive to promote universal access with equal opportunities for all to scientific knowledge and the creation and dissemination of scientific and technical information, including open access initiatives for scientific publishing.

- 46. In building the Information Society, States are strongly urged to take steps with a view to the avoidance of, and refrain from, any unilateral measure not in accordance with international law and the Charter of the United Nations that impedes the full achievement of economic and social development by the population of the affected countries, and that hinders the well-being of their population.

See also

| Library resources about Digital divide |

- Achievement gap

- Civic opportunity gap

- Computer technology for developing areas

- Digital divide by country

- Digital divide in Canada

- Digital divide in China

- Digital divide in South Africa

- Digital divide in Thailand

- Digital rights

- Digital Society Day (October 17 in India)

- Global Internet usage

- Information society

- International communication

- Internet geography

- Internet governance

- List of countries by Internet connection speeds

- Light-weight Linux distribution

- National broadband plans from around the world

- NetDay

- Rural Internet

Groups devoted to digital divide issues

- Center for Digital Inclusion

- Digital Textbook a South Korean Project that intends to distribute tablet notebooks to elementary school students.

- Inveneo

- TechChange

- United Nations Information and Communication Technologies Task Force

Sources

![]()

References

- U.S. Department of Commerce, National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA). (1995). Falling through the net: A survey of the have nots in rural and urban America. Retrieved from, http://www.ntia.doc.gov/ntiahome/fallingthru.html.

- Compaine, B.M. (2001). The digital divide: Facing a crisis or creating a myth? Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press

- "Percentage of Individuals using the Internet 2000-2012", International Telecommunications Union (Geneva), June 2013, retrieved June 22, 2013

- Hilbert, Martin (2013). "Technological information inequality as an incessantly moving target: The redistribution of information and communication capacities between 1986 and 2010" (PDF). Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. 65 (4): 821–835. doi:10.1002/asi.23020.

- Eszter Hargittai. The Digital Divide and What to Do About It. New Economy Handbook, p. 824, 2003.

- Karen Mossberger (2003). Virtual Inequality: Beyond the Digital Divide. Georgetown University Press

- Blau, A (2002). "Access isn't enough: Merely connecting people and computers won't close the digital divide". American Libraries. 33 (6): 50–52.

- Graham, Mark (2014). "The Knowledge Based Economy and Digital Divisions of Labour". Pages 189-195 in Companion to Development Studies, 3rd edition, V. Desai, and R. Potter (eds). Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-1-44-416724-5 (paperback). ISBN 978-0-415-82665-5 (hardcover).

- "Digital Divide and Global Inequalities in Education"

- Hilbert, Martin (2011). "The end justifies the definition: The manifold outlooks on the digital divide and their practical usefulness for policy-making" (PDF). Telecommunications Policy. 35 (8): 715–736. doi:10.1016/j.telpol.2011.06.012.

- "Dashboard - Digital inclusion". GOV.UK. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- https://digitalparticipation.scot/

- "Tech Partnership Legacy". Thetechpartnership.com. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- "Media literacy". Ofcom. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- Rouse, Margaret. "What is digital accessibility? - Definition from WhatIs.com". Whatis.techtarget.com. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- "NDIA". 2017. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- Bowles, Nellie (October 26, 2018). "The Digital Gap Between Rich and Poor Kids Is Not What We Expected". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- Norris, P. (2001). Digital Divide: Civic Engagement, Information Poverty and the Internet Worldwide Archived October 24, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Cambridge University Press.

- Chinn, Menzie D. and Robert W. Fairlie. (2004). The Determinants of the Global Digital Divide: A Cross-Country Analysis of Computer and Internet Penetration. Economic Growth Center. Retrieved from https://www.econ.yale.edu/growth_pdf/cdp881.pdf%5B%5D

- Zickuher, Kathryn. 2011. Generations and their gadgets. Pew Internet & American Life Project.

- Hilbert, Martin (2016). "The bad news is that the digital access divide is here to stay: Domestically installed bandwidths among 172 countries for 1986–2014". Telecommunications Policy. 40 (6): 567–581. doi:10.1016/j.telpol.2016.01.006.

- Dutton, W.H.; Gillett, S.E.; McKnight, L.W.; Peltu, M. (2004). "Bridging broadband internet divides". Journal of Information Technology. 19 (1): 28–38. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jit.2000007.

- Kathryn zickuhr. Who's not online and why? Pew Research Center, 2013.

- SciDevNet (2014) How mobile phones increased the digital divide; http://www.scidev.net/global/data/scidev-net-at-large/how-mobile-phones-increased-the-digital-divide.html

- Abdalhakim, Hawaf., (2009). An innovated objective digital divide measure, Journal of Communication and Computer, Volume 6, No.12 (Serial No.61), USA.

- Paschalidou, Georgia, (2011), Digital divide and disparities in the use of new technologies, https://dspace.lib.uom.gr/bitstream/2159/14899/6/PaschalidouGeorgiaMsc2011.pdf

- Figures 11 and 12 in "Mapping the dimensions and characteristics of the world’s technological communication capacity during the period of digitization (1986–2007/2010)". Hilbert, Martin. Working paper INF/15-E, International Telecommunications Union. December 2, 2011.

- Hilbert, Martin (2010). "Information Societies or "ICT Equipment Societies?" Measuring the Digital Information-Processing Capacity of a Society in Bits and Bytes". The Information Society. 26 (3): 157–178. doi:10.1080/01972241003712199. S2CID 1552670.

- "Mapping the dimensions and characteristics of the world’s technological communication capacity during the period of digitization", Martin Hilbert (2011), Presented at the 9th World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators Meeting, Mauritius: International Telecommunication Union (ITU); free access to the article can be found here: http://www.itu.int/ITU-D/ict/wtim11/documents/inf/015INF-E.pdf

- "Chapter 5: Measuring communication capacity in bits and bytes", in Measuring the report Information Society 2012; ITU (International Telecommunication Union) (2012).

- Mun-cho, K. & Jong-Kil, K. (2001). Digital divide: conceptual discussions and prospect, In W. Kim, T. Wang Ling, Y.j. Lee & S.S. Park (Eds.), The human society and the Internet: Internet-related socio-economic Issues, First International Conference, Seoul, Korea: Proceedings, Springer, New York, NY.

- Aqili, S.; Moghaddam, A. (2008). "Bridging the digital divide: The role of librarians and information professionals in the third millennium". Electronic Library. 26 (2): 226–237. doi:10.1108/02640470810864118.

- "I'd blush if I could: closing gender divides in digital skills through education" (PDF). UNESCO, EQUALS Skills Coalition. 2019.

- Mariscal, J., Mayne, G., Aneja, U. and Sorgner, A. 2018. Bridging the Gender Digital Gap. Buenos Aires, CARI/CIPPEC.

- Girl Effect and Vodafone Foundation. 2018. Real Girls, Real Lives, Connected. London, Girl Effect and Vodafone Foundation.

- Fjeld, A. 2018. AI: A Consumer Perspective. March 13, 2018. New York, LivePerson.

- Livingston, Gretchen. 2010. Latinos and Digital Technology, 2010. Pew Hispanic Center

- Ramalingam A, Kar SS (2014). "Is there a digital divide among school students? an exploratory study from Puducherry". J Educ Health Promot. 3: 30. doi:10.4103/2277-9531.131894 (inactive June 6, 2020). PMC 4089106. PMID 25013823.

- Ryan Kim (October 25, 2011). "'App gap' emerges highlighting savvy mobile children". GigaOM.

- Mossberger, Karen; Tolbert, Caroline J.; Gilbert, Michele (2006). "Race, Place, and Information Technology (IT)". Urban Affairs Review. 41 (5): 583–620. doi:10.1177/1078087405283511.

- Lawton, Tait. "15 Years of Chinese Internet Usage in 13 Pretty Graphs". NanjingMarketingGroup.com. CNNIC. Archived from the original on April 22, 2014.

- Wang, Wensheng. Impact of ICTs on Farm Households in China, ZEF of University Bonn, 2001

- Statistical Survey Report on the Internet Development in China. China Internet Network Information Center. January 2007. From "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 14, 2013. Retrieved July 5, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Guillen, M. F.; Suárez, S. L. (2005). "Explaining the global digital divide: Economic, political and sociological drivers of cross-national internet use". Social Forces. 84 (2): 681–708. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.649.2813. doi:10.1353/sof.2006.0015.

- Wilson, III. E.J. (2004). The Information Revolution and Developing Countries. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

- Carr, Deborah (2007). "The Global Digital Divide". Contexts. 6 (3): 58. doi:10.1525/ctx.2007.6.3.58. ProQuest 219574259.

- Wilson, Kenneth, Jennifer Wallin, and Christa Reiser. "Social Science Computer Review." Social Science Computer Review. 2003; 21(2): 133-143 PDF

- Hilbert, Martin (2010). "When is Cheap, Cheap Enough to Bridge the Digital Divide? Modeling Income Related Structural Challenges of Technology Diffusion in Latin America" (PDF). World Development. 38 (5): 756–770. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.11.019.

- Hilbert, Martin (November–December 2011). "Digital gender divide or technologically empowered women in developing countries? A typical case of lies, damned lies, and statistics" (PDF). Women's Studies International Forum. 34 (6): 479–489. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2011.07.001.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schliefe, Katrin (February 2007). "Regional Versus. Individual Aspects of the Digital Divide in Germany" (PDF). Retrieved October 21, 2017.

- Rubin, R.E. (2010). Foundations of library and information science. 178-179. New York: Neal-Schuman Publishers.

- Galperin, H. (2010). Goodbye digital divide, Hello digital confusion? A critical embrace of the emerging ICT4D consensus. Information Technologies and International Development, 6 Special Edition, 53–55

- National Telecommunications & Information Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. (1995). Falling through the net: A survey of the‘have nots’ in rural and urban America. Washington, D.C. Retrieved fromhttp://www.ntia.doc.gov/ntiahome/fallingthru.html

- National Telecommunications & Information Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. (1998). Falling through the net II: New data on the digital divide. Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://www.ntia.doc.gov/report/1998/falling-through-net-ii-new-data-digital-divide

- National Telecommunications & Information Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. (1999). Falling through the net: Defining the digital divide. Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://www.ntia.doc.gov/report/1999/falling-through-net-defining-digital-divide

- National Telecommunications & Information Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. (1995). Falling through the net: A survey of the‘have nots’ in rural and urban America. Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://www.ntia.doc.gov/ntiahome/fallingthru.html

- https://www.freepress.net/sites/default/files/legacy-policy/digital_denied_free_press_report_december_2016.pdf

- "Americans living with disability and their technology profile". Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. Washington. January 21, 2011. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- "Online hate crime against disabled people rises by a third". the Guardian. May 10, 2019. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- "'He can't speak to defend himself, I can'". BBC News. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- Cooper, J. (2008). "The digital divide: the special case of gender" (PDF). Journal of Computer Assisted Learning (22).

- Mundy, Liza (April 2017). "Why Is Silicon Valley So Awful to Women?". The Atlantic. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- Dastin, Jeffrey (October 10, 2018). "Amazon scraps secret AI recruiting tool that showed bias against women". Reuters. Retrieved April 17, 2020.