Postpositivism

In philosophy and models of scientific inquiry, postpositivism (also called postempiricism) is a metatheoretical stance that critiques and amends positivism.[1] While positivists emphasize independence between the researcher and the researched person (or object), postpositivists argue that theories, hypotheses, background knowledge and values of the researcher can influence what is observed.[2] Postpositivists pursue objectivity by recognizing the possible effects of biases.[2][3][4] While positivists emphasize quantitative methods, postpositivists consider both quantitative and qualitative methods to be valid approaches.[4]

| Postmodernism |

|---|

| Preceded by Modernism |

| Postmodernity |

| Fields |

| Criticism of postmodernism |

Philosophy

Epistemology

Postpositivists believe that human knowledge is based not on a priori assessments from an objective individual,[4] but rather upon human conjectures. As human knowledge is thus unavoidably conjectural, the assertion of these conjectures are warranted, or more specifically, justified by a set of warrants, which can be modified or withdrawn in the light of further investigation. However, postpositivism is not a form of relativism, and generally retains the idea of objective truth.

Ontology

Postpositivists believe that a reality exists, but, unlike positivists, they believe reality can be known only imperfectly[3] and probabilistically.[2] Postpositivists also draw from social constructionism in forming their understanding and definition of reality.[3]

Axiology

While positivists believe that research is or can be value-free or value-neutral, postpositivists take the position that bias is undesired but inevitable, and therefore the investigator must work to detect and try to correct it. Postpositivists work to understand how their axiology (i.e. values and beliefs) may have influenced their research, including through their choice of measures, populations, questions, and definitions, as well as through their interpretation and analysis of their work.[3]

History

Historians identify two types of positivism: classical positivism, an empirical tradition first described by Henri de Saint-Simon and Auguste Comte,[1] and logical positivism, which is most strongly associated with the Vienna Circle, which met near Vienna, Austria, in the 1920s and 1930s.[3] Postpositivism is the name D.C. Phillips[3] gave to a group of critiques and amendments which apply to both forms of positivism.[3]

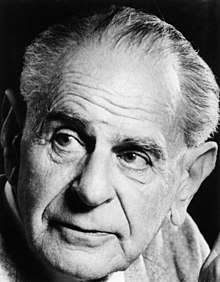

One of the first thinkers to criticize logical positivism was Sir Karl Popper. He advanced falsification in lieu of the logical positivist idea of verificationism.[3] Falsificationism argues that it is impossible to verify that beliefs about universals or unobservables are true, though it is possible to reject false beliefs if they are phrased in a way amenable to falsification. Thomas Kuhn's idea of paradigm shifts offers a broader critique of logical positivism, arguing that it is not simply individual theories but whole worldviews that must occasionally shift in response to evidence.[3]

Postpositivism is not a rejection of the scientific method, but rather a reformation of positivism to meet these critiques. It reintroduces the basic assumptions of positivism: the possibility and desirability of objective truth, and the use of experimental methodology. The work of philosophers Nancy Cartwright and Ian Hacking are representative of these ideas. Postpositivism of this type is described in social science guides to research methods.[5]

Structure of a postpositivist theory

Robert Dubin describes the basic components of a postpositivist theory as being composed of basic "units" or ideas and topics of interest, "laws of interactions" among the units, and a description of the "boundaries" for the theory.[3] A postpositivist theory also includes "empirical indicators" to connect the theory to observable phenomena, and hypotheses that are testable using the scientific method.[3]

According to Thomas Kuhn, a postpositivist theory can be assessed on the basis of whether it is "accurate", "consistent", "has broad scope", "parsimonious", and "fruitful".[3]

Main publications

- Karl Popper (1934) Logik der Forschung, rewritten in English as The Logic of Scientific Discovery (1959)

- Thomas Kuhn (1962) The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

- Karl Popper (1963) Conjectures and Refutations

- Ian Hacking (1983) Representing and Intervening

- Andrew Pickering (1984) Constructing Quarks

- Peter Galison (1987) How Experiments End

- Nancy Cartwright (1989) Nature's Capacities and Their Measurement

Notes

- Bergman, Mats (2016). "Positivism". The International Encyclopedia of Communication Theory and Philosophy. p. 1–5. doi:10.1002/9781118766804.wbiect248. ISBN 9781118766804.

- Robson, Colin (2002). Real World Research. A Resource for Social Scientists and Practitioner-Researchers (Second Edition). Malden: Blackwell. p. 624. ISBN 978-0-631-21305-5.

- Miller, Katherine (2007). Communication theories : perspectives, processes, and contexts (2nd ed.). Beijing: Peking University Press. p. 35–45. ISBN 9787301124314.

- Taylor, Thomas R.; Lindlof, Bryan C. (2011). Qualitative communication research methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE. p. 5–13. ISBN 978-1412974738.

- Trochim, William. "Social Research Methods Knowledge Base". socialresearchmethods.net.

References

- Alexander, J.C. (1995), Fin De Siecle Social Theory: Relativism, Reductionism and The Problem of Reason, London; Verso.

- Phillips, D.C. & Nicholas C. Burbules (2000): Postpositivism and Educational Research. Lanham & Boulder: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Zammito, John H. (2004): A Nice Derangement of Epistemes. Post-positivism in the study of Science from Quine to Latour. Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press.

- Popper, K. (1963), Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge, London; Routledge.

- Moore, R. (2009), Towards the Sociology of Truth, London; Continuum.

External links

| Library resources about Postpositivism |

.svg.png)