Routing

Routing is the process of selecting a path for traffic in a network or between or across multiple networks. Broadly, routing is performed in many types of networks, including circuit-switched networks, such as the public switched telephone network (PSTN), and computer networks, such as the Internet.

In packet switching networks, routing is the higher-level decision making that directs network packets from their source toward their destination through intermediate network nodes by specific packet forwarding mechanisms. Packet forwarding is the transit of network packets from one network interface to another. Intermediate nodes are typically network hardware devices such as routers, gateways, firewalls, or switches. General-purpose computers also forward packets and perform routing, although they have no specially optimized hardware for the task.

The routing process usually directs forwarding on the basis of routing tables. Routing tables maintain a record of the routes to various network destinations. Routing tables may be specified by an administrator, learned by observing network traffic or built with the assistance of routing protocols.

Routing, in a narrower sense of the term, often refers to IP routing and is contrasted with bridging. IP routing assumes that network addresses are structured and that similar addresses imply proximity within the network. Structured addresses allow a single routing table entry to represent the route to a group of devices. In large networks, structured addressing (routing, in the narrow sense) outperforms unstructured addressing (bridging). Routing has become the dominant form of addressing on the Internet. Bridging is still widely used within local area networks.

Delivery schemes

| Routing schemes |

|---|

| Unicast |

| Broadcast |

| Multicast |

| Anycast |

| Geocast |

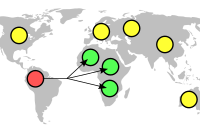

Routing schemes differ in how they deliver messages:

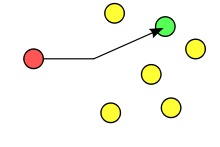

- Unicast delivers a message to a single specific node using a one-to-one association between a sender and destination: each destination address uniquely identifies a single receiver endpoint.

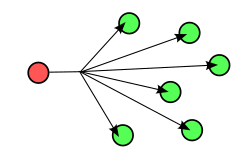

- Broadcast delivers a message to all nodes in the network using a one-to-all association; a single datagram from one sender is routed to all of the possibly multiple endpoints associated with the broadcast address. The network automatically replicates datagrams as needed to reach all the recipients within the scope of the broadcast, which is generally an entire network subnet.

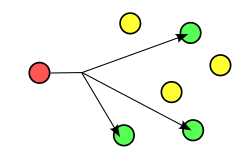

- Multicast delivers a message to a group of nodes that have expressed interest in receiving the message using a one-to-many-of-many or many-to-many-of-many association; datagrams are routed simultaneously in a single transmission to many recipients. Multicast differs from broadcast in that the destination address designates a subset, not necessarily all, of the accessible nodes.

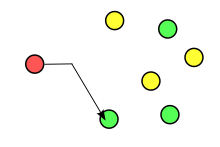

- Anycast delivers a message to any one out of a group of nodes, typically the one nearest to the source using a one-to-one-of-many association where datagrams are routed to any single member of a group of potential receivers that are all identified by the same destination address. The routing algorithm selects the single receiver from the group based on which is the nearest according to some distance measure.

- Geocast delivers a message to a group of nodes in a network based on their geographic location. It is a specialized form of multicast addressing used by some routing protocols for mobile ad hoc networks.

Unicast is the dominant form of message delivery on the Internet. This article focuses on unicast routing algorithms.

Topology distribution

With static routing, small networks may use manually configured routing tables. Larger networks have complex topologies that can change rapidly, making the manual construction of routing tables unfeasible. Nevertheless, most of the public switched telephone network (PSTN) uses pre-computed routing tables, with fallback routes if the most direct route becomes blocked (see routing in the PSTN).

Dynamic routing attempts to solve this problem by constructing routing tables automatically, based on information carried by routing protocols, allowing the network to act nearly autonomously in avoiding network failures and blockages. Dynamic routing dominates the Internet. Examples of dynamic-routing protocols and algorithms include Routing Information Protocol (RIP), Open Shortest Path First (OSPF) and Enhanced Interior Gateway Routing Protocol (EIGRP).

Distance vector algorithms

Distance vector algorithms use the Bellman–Ford algorithm. This approach assigns a cost number to each of the links between each node in the network. Nodes send information from point A to point B via the path that results in the lowest total cost (i.e. the sum of the costs of the links between the nodes used).

When a node first starts, it only knows of its immediate neighbors and the direct cost involved in reaching them. (This information — the list of destinations, the total cost to each, and the next hop to send data to get there — makes up the routing table, or distance table.) Each node, on a regular basis, sends to each neighbor node its own current assessment of the total cost to get to all the destinations it knows of. The neighboring nodes examine this information and compare it to what they already know; anything that represents an improvement on what they already have, they insert in their own table. Over time, all the nodes in the network discover the best next hop and total cost for all destinations.

When a network node goes down, any nodes that used it as their next hop discard the entry and convey the updated routing information to all adjacent nodes, which in turn repeat the process. Eventually, all the nodes in the network receive the updates and discover new paths to all the destinations that don't involve the down node.

Link-state algorithms

When applying link-state algorithms, a graphical map of the network is the fundamental data used for each node. To produce its map, each node floods the entire network with information about the other nodes it can connect to. Each node then independently assembles this information into a map. Using this map, each router independently determines the least-cost path from itself to every other node using a standard shortest paths algorithm such as Dijkstra's algorithm. The result is a tree graph rooted at the current node, such that the path through the tree from the root to any other node is the least-cost path to that node. This tree then serves to construct the routing table, which specifies the best next hop to get from the current node to any other node.

Optimized Link State Routing algorithm

A link-state routing algorithm optimized for mobile ad hoc networks is the optimized Link State Routing Protocol (OLSR).[1] OLSR is proactive; it uses Hello and Topology Control (TC) messages to discover and disseminate link-state information through the mobile ad hoc network. Using Hello messages, each node discovers 2-hop neighbor information and elects a set of multipoint relays (MPRs). MPRs distinguish OLSR from other link-state routing protocols.

Path-vector protocol

Distance vector and link-state routing are both intra-domain routing protocols. They are used inside an autonomous system, but not between autonomous systems. Both of these routing protocols become intractable in large networks and cannot be used in inter-domain routing. Distance vector routing is subject to instability if there are more than a few hops in the domain. Link state routing needs significant resources to calculate routing tables. It also creates heavy traffic due to flooding.

Path-vector routing is used for inter-domain routing. It is similar to distance vector routing. Path-vector routing assumes that one node (there can be many) in each autonomous system acts on behalf of the entire autonomous system. This node is called the speaker node. The speaker node creates a routing table and advertises it to neighboring speaker nodes in neighboring autonomous systems. The idea is the same as distance vector routing except that only speaker nodes in each autonomous system can communicate with each other. The speaker node advertises the path, not the metric, of the nodes in its autonomous system or other autonomous systems.

The path-vector routing algorithm is similar to the distance vector algorithm in the sense that each border router advertises the destinations it can reach to its neighboring router. However, instead of advertising networks in terms of a destination and the distance to that destination, networks are advertised as destination addresses and path descriptions to reach those destinations. The path, expressed in terms of the domains (or confederations) traversed so far, is carried in a special path attribute that records the sequence of routing domains through which the reachability information has passed. A route is defined as a pairing between a destination and the attributes of the path to that destination, thus the name, path-vector routing; The routers receive a vector that contains paths to a set of destinations.[2]

Path selection

Path selection involves applying a routing metric to multiple routes to select (or predict) the best route. Most routing algorithms use only one network path at a time. Multipath routing and specifically equal-cost multi-path routing techniques enable the use of multiple alternative paths.

In computer networking, the metric is computed by a routing algorithm, and can cover information such as bandwidth, network delay, hop count, path cost, load, maximum transmission unit, reliability, and communication cost.[3] The routing table stores only the best possible routes, while link-state or topological databases may store all other information as well.

In case of overlapping or equal routes, algorithms consider the following elements in priority order to decide which routes to install into the routing table:

- Prefix length: A matching route table entry with a longer subnet mask is always preferred as it specifies the destination more exactly.

- Metric: When comparing routes learned via the same routing protocol, a lower metric is preferred. Metrics cannot be compared between routes learned from different routing protocols.

- Administrative distance: When comparing route table entries from different sources such as different routing protocols and static configuration, a lower administrative distance indicates a more reliable source and thus a preferred route.

Because a routing metric is specific to a given routing protocol, multi-protocol routers must use some external heuristic to select between routes learned from different routing protocols. Cisco routers, for example, attribute a value known as the administrative distance to each route, where smaller administrative distances indicate routes learned from a protocol assumed to be more reliable.

A local administrator can set up host-specific routes that provide more control over network usage, permits testing, and better overall security. This is useful for debugging network connections or routing tables.

In some small systems, a single central device decides ahead of time the complete path of every packet. In some other small systems, whichever edge device injects a packet into the network decides ahead of time the complete path of that particular packet. In both of these systems, that route-planning device needs to know a lot of information about what devices are connected to the network and how they are connected to each other. Once it has this information, it can use an algorithm such as A* search algorithm to find the best path.

In high-speed systems, there are so many packets transmitted every second that it is infeasible for a single device to calculate the complete path for each and every packet. Early high-speed systems dealt with this by setting up a circuit switching relay channel once for the first packet between some source and some destination; later packets between that same source and that same destination continue to follow the same path without recalculating until the channel teardown. Later high-speed systems inject packets into the network without any one device ever calculating a complete path for that packet—multiple agents.

In large systems, there are so many connections between devices, and those connections change so frequently, that it is infeasible for any one device to even know how all the devices are connected to each other, much less calculate a complete path through them. Such systems generally use next-hop routing.

Most systems use a deterministic dynamic routing algorithm: When a device chooses a path to a particular final destination, that device always chooses the same path to that destination until it receives information that makes it think some other path is better. A few routing algorithms do not use a deterministic algorithm to find the "best" link for a packet to get from its original source to its final destination. Instead, to avoid congestion in switched systems or network hot spots in packet systems, a few algorithms use a randomized algorithm—Valiant's paradigm—that routes a path to a randomly picked intermediate destination, and from there to its true final destination.[4][5] In many early telephone switches, a randomizer was often used to select the start of a path through a multistage switching fabric.

Depending on the application for which path selection is performed, different metrics can be used. For example, for web requests one can use minimum latency paths to minimize web page load time, or for bulk data transfers one can choose the least utilized path to balance load across the network and increase throughput. A popular path selection objective is to reduce the average completion times of traffic flows and the total network bandwidth consumption which basically leads to better use of network capacity. Recently, a path selection metric was proposed that computes the total number of bytes scheduled on the edges per path as selection metric.[6] An empirical analysis of several path selection metrics, including this new proposal, has been made available.[7]

Multiple agents

In some networks, routing is complicated by the fact that no single entity is responsible for selecting paths; instead, multiple entities are involved in selecting paths or even parts of a single path. Complications or inefficiency can result if these entities choose paths to optimize their own objectives, which may conflict with the objectives of other participants.

A classic example involves traffic in a road system, in which each driver picks a path that minimizes their travel time. With such routing, the equilibrium routes can be longer than optimal for all drivers. In particular, Braess' paradox shows that adding a new road can lengthen travel times for all drivers.

In another model, for example, used for routing automated guided vehicles (AGVs) on a terminal, reservations are made for each vehicle to prevent simultaneous use of the same part of an infrastructure. This approach is also referred to as context-aware routing.[8]

The Internet is partitioned into autonomous systems (ASs) such as internet service providers (ISPs), each of which controls routes involving its network, at multiple levels. First, AS-level paths are selected via the BGP protocol, which produces a sequence of ASs through which packets flow. Each AS may have multiple paths, offered by neighboring ASs, from which to choose. Its decision often involves business relationships with these neighboring ASs,[9] which may be unrelated to path quality or latency. Second, once an AS-level path has been selected, there are often multiple corresponding router-level paths, in part because two ISPs may be connected in multiple locations. In choosing the single router-level path, it is common practice for each ISP to employ hot-potato routing: sending traffic along the path that minimizes the distance through the ISP's own network—even if that path lengthens the total distance to the destination.

Consider two ISPs, A and B. Each has a presence in New York, connected by a fast link with latency 5 ms—and each has a presence in London connected by a 5 ms link. Suppose both ISPs have trans-Atlantic links that connect their two networks, but A's link has latency 100 ms and B's has latency 120 ms. When routing a message from a source in A 's London network to a destination in B 's New York network, A may choose to immediately send the message to B in London. This saves A the work of sending it along an expensive trans-Atlantic link, but causes the message to experience latency 125 ms when the other route would have been 20 ms faster.

A 2003 measurement study of Internet routes found that, between pairs of neighboring ISPs, more than 30% of paths have inflated latency due to hot-potato routing, with 5% of paths being delayed by at least 12 ms. Inflation due to AS-level path selection, while substantial, was attributed primarily to BGP's lack of a mechanism to directly optimize for latency, rather than to selfish routing policies. It was also suggested that, were an appropriate mechanism in place, ISPs would be willing to cooperate to reduce latency rather than use hot-potato routing.[10]

Such a mechanism was later published by the same authors, first for the case of two ISPs[11] and then for the global case.[12]

Route analytics

As the Internet and IP networks become mission critical business tools, there has been increased interest in techniques and methods to monitor the routing posture of networks. Incorrect routing or routing issues cause undesirable performance degradation, flapping and/or downtime. Monitoring routing in a network is achieved using route analytics tools and techniques.

Centralized routing

In networks where a logically centralized control is available over the forwarding state, for example, using Software-defined networking, routing techniques can be used that aim to optimize global and network-wide performance metrics. This has been used by large internet companies that operate many data centers in different geographical locations attached using private optical links examples of which includes Microsoft's Global WAN,[13] Facebook's Express Backbone,[14] and Google's B4.[15] Global performance metrics to optimize include maximizing network utilization, minimizing traffic flow completion times, and maximizing the traffic delivered prior to specific deadlines. Minimizing flow completion times over private WAN, particularly, has not received much attention from the research community. However, with the increasing number of businesses that operate globally distributed data centers connected using private inter-data center networks, it is likely to see increasing research effort in this realm.[16] A very recent work on reducing the completion times of flows over private WAN discusses modeling routing as a graph optimization problem by pushing all the queuing to the end-points. Authors also propose a heuristic to solve the problem efficiently while sacrificing negligible performance.[17]

See also

- Collective routing

- Deflection routing

- Edge Disjoint Shortest Pair Algorithm

- Flood search routing

- Fuzzy routing

- Geographic routing

- Heuristic routing

- Path computation element (PCE)

- Policy-based routing

- Wormhole routing

- Small world routing

- Turn restriction routing

References

- RFC 3626

- RFC 1322

- A Survey on Routing Metrics (PDF), February 10, 2007, retrieved 2020-05-04

- Michael Mitzenmacher; Andréa W. Richa; Ramesh Sitaraman. "The Power of Two Random Choices: A Survey of Techniques and Results". Section "Randomized Protocols for Circuit Routing". p. 34.

- Stefan Haas. "The IEEE 1355 Standard: Developments, Performance and Application in High Energy Physics". 1998. p. 15. quote: "To eliminate network hot spots, ... a two phase routing algorithm. This involves every packet being first sent to a randomly chosen intermediate destination; from the intermediate destination it is forwarded to its final destination. This algorithm, referred to as Universal Routing, is designed to maximize capacity and minimize delay under conditions of heavy load."

- M. Noormohammadpour; C. S. Raghavendra. (2018). "Poster Abstract: Minimizing Flow Completion Times using Adaptive Routing over Inter-Datacenter Wide Area Networks".

- M. Noormohammadpour; C. S. Raghavendra. (2018). "Minimizing Flow Completion Times using Adaptive Routing over Inter-Datacenter Wide Area Networks".

- Jonne Zutt, Arjan J.C. van Gemund, Mathijs M. de Weerdt, and Cees Witteveen (2010). Dealing with Uncertainty in Operational Transport Planning. In R.R. Negenborn and Z. Lukszo and H. Hellendoorn (Eds.) Intelligent Infrastructures, Ch. 14, pp. 355–382. Springer.

- Matthew Caesar and Jennifer Rexford. BGP routing policies in ISP networks. IEEE Network Magazine, special issue on Interdomain Routing, Nov/Dec 2005.

- Neil Spring, Ratul Mahajan, and Thomas Anderson. Quantifying the Causes of Path Inflation. Proc. SIGCOMM 2003.

- Ratul Mahajan, David Wetherall, and Thomas Anderson. Negotiation-Based Routing Between Neighboring ISPs. Proc. NSDI 2005.

- Ratul Mahajan, David Wetherall, and Thomas Anderson. Mutually Controlled Routing with Independent ISPs. Proc. NSDI 2007.

- Khalidi, Yousef (March 15, 2017). "How Microsoft builds its fast and reliable global network".

- "Building Express Backbone: Facebook's new long-haul network". May 1, 2017.

- "Inside Google's Software-Defined Network". May 14, 2017.

- Noormohammadpour, Mohammad; Raghavendra, Cauligi (16 July 2018). "Datacenter Traffic Control: Understanding Techniques and Tradeoffs". IEEE Communications Surveys and Tutorials. 20 (2): 1492–1525. arXiv:1712.03530. doi:10.1109/COMST.2017.2782753.

- Noormohammadpour, Mohammad; Srivastava, Ajitesh; Raghavendra, Cauligi (2018). "On Minimizing the Completion Times of Long Flows over Inter-Datacenter WAN". IEEE Communications Letters. 22 (12): 2475–2478. arXiv:1810.00169. Bibcode:2018arXiv181000169N. doi:10.1109/LCOMM.2018.2872980.

Further reading

- Ash, Gerald (1997). Dynamic Routing in Telecommunication Networks. McGraw–Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-006414-0.

- Doyle, Jeff & Carroll, Jennifer (2005). Routing TCP/IP, Volume I, Second Ed. Cisco Press. ISBN 978-1-58705-202-6.Ciscopress ISBN 1-58705-202-4

- Doyle, Jeff & Carroll, Jennifer (2001). Routing TCP/IP, Volume II. Cisco Press. ISBN 978-1-57870-089-9.Ciscopress ISBN 1-57870-089-2

- Huitema, Christian (2000). Routing in the Internet, Second Ed. Prentice–Hall. ISBN 978-0-321-22735-5.

- Kurose, James E. & Ross, Keith W. (2004). Computer Networking, Third Ed. Benjamin/Cummings. ISBN 978-0-321-22735-5.

- Medhi, Deepankar & Ramasamy, Karthikeyan (2007). Network Routing: Algorithms, Protocols, and Architectures. Morgan Kaufmann. ISBN 978-0-12-088588-6.

External links

| Wikiversity has learning resources about Routing |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Routing. |

- Count-To-Infinity Problem

- "Stability Features" are ways of avoiding the "count to infinity" problem.

- Cisco IT Case Studies about Routing and Switching

- "IP Routing and Subnets". www.eventhelix.com. Retrieved 2018-04-28.