E-democracy

E-democracy (a combination of the words electronic and democracy), also known as digital democracy or Internet democracy, is the use of information and communication technology (ICT) in political and governance processes.[1] It incorporates 21st-century information and communications technology to promote democracy; such technologies include civic technology and government technology. It is a form of government in which all adult citizens are presumed to be eligible to participate equally in the proposal, development and creation of laws.[2]

| Part of a series on |

| Politics |

|---|

.svg.png) |

|

Primary topics |

|

Academic disciplines |

|

Organs of government |

| Politics Portal |

| Internet |

|---|

An Opte Project visualization of routing paths through a portion of the Internet |

|

|

| Part of the Politics series | ||||||||

| Basic forms of government | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power structure | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Power source | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Power ideology | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Politics portal | ||||||||

E-democracy encompasses social, economic and cultural conditions that enable the free and equal practice of political self-determination. According to Sharique Hassan Manazir,[3] digital inclusion is an inherent necessity of an e-democracy.[4]

Goals

Human rights

The spread of free information through the internet has encouraged freedom and human development. The internet is used for promoting human rights—including free speech, religion, expression, peaceful assembly, government accountability, and the right of knowledge and understanding—that support democracy. An E-democracy process has been recently proposed in a scientific article[5] for solving a question that has crucial importance for all humans in the 21st century: "As planet Earth citizens, will you stop the climate from warming?" The author proposes to use a cell-phone for answering this question during the Olympic Games in Pyeongchang 2018 and Tokyo 2020.

Expanding democracy

The Internet has several attributes that encourage thinking about it as a democratic medium. The lack of centralized control makes censorship difficult. There are other parallels in the social design in the early days of the internet, such as the strongly libertarian support for free speech, the sharing culture that permeated nearly all aspects of Internet use, and the outright prohibition on commercial use by the National Science Foundation. Another example is the unmediated mass communication on the internet, such as through newsgroups, chat rooms, and MUDs. This communication ignored the boundaries established with broadcast media, such as newspapers or radio, and with one-to-one media, such as letters or landline telephones. Finally, because the Internet is a massive digital network with open standards, universal and inexpensive access to a wide variety of communication media and models could actually be attained.[6]

Some practical issues involving e-democracy include: effective participation; voting equality at decision stage; enlightened understanding; control of the agenda; and inclusiveness.[7] Systemic issues may include cyber-security concerns and protection of sensitive data from third parties.

Improving Democracy

Strictly speaking, modern democracies are generally representative democracies, where citizens elect representatives to manage the creation and implementation of laws, policies, and regulations on their behalf, in contrast to direct democracies in which citizens retain that responsibility. They may be referred to as more or less "democratic" depending on how well the government represents the will or interest of the people. A shift to E-democracy would in effect devolve political power from elected representatives to the individual.

In America, politics have become reliant on the Internet because the Internet is the primary source of information for most Americans. The Internet educates people on democracy, helping people stay up to date with what is happening in their government. Online advertising is becoming more popular for political candidates and group's opinions on propositions.[8] For many the Internet is often the primary resource for information. The reason for this, and especially among younger voters, is that it is easy and reliable when used correctly, thus lowering an individual's workload. The innate usability of search engines, such as Google, results in increased citizen engagement with research and political issues. Social networks allow people to express their opinions about the government through an alias, anonymously and judgment-free.[9] Due to the Internets' size and decentralized structure, any individual has the potential to go viral and gain influence over a large number of others.

The Internet enables citizens to get and post information about politicians, and it allows those politicians to get advice from the people in larger numbers. This collective decision making and problem-solving gives more power to the citizens and helps politicians make decisions faster. This creates a more productive society that can handle problems faster and more efficiently. Getting feedback and advice from the American population is a large part of a politician's job and the Internet allows them to function effectively with larger numbers of people's opinions. With this heightened ability to communicate with the public, the American government is able to function more capably and effectively as a Democracy.[10]

The American election of 2016 is an example, Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton made good use of Twitter, attempting to shape perceptions on their behalf, whilst using social media to transmit the idea that authorities are also ‘normal’, and they can communicate through a Twitter account just like everyone does. In other words, nowadays, any ordinary person can research on political causes and events at any time just by searching something on Google. Also, the various different forms of sharing one’s political beliefs through interactive chats and online posts on social media, such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, connects people who part one’s same views (Sarwar & Soomro, 2013, pp. 216–226)[11]

Generation X became disillusioned that even large-scale public protests such as the UK miners' strike (1984–1985) were seen to fail a decade before information technology became generally available to individual citizens.[12] E-democracy is sometimes seen as a remedy to the insular nature, concentrated power, and lack of post-election accountability in traditional democratic process organized mostly around political parties. Tom Watson, the Deputy Leader of the UK Labour Party, said:

It feels like the Labour frontbench is further away from our members than at any point in our history and the digital revolution can help bring the party closer together ... I'm going to ask our NEC to see whether we can have digital branches and digital delegates to the conference. Not replacing what we do but providing an alternative platform. It's a way of organising for a different generation of people who do their politics differently, get their news differently.[13]

Digital Inclusion

Digital Inclusion is essential for citizen participation in public policy formulation for a healthy Digital Democracy through equal participation of all section of society in any democracy irrespective of citizen's income level, education level, gender, religion, color, race, language used, physical and mental health etc. Any public policy formulated without including any specific section of society will always remain non-inclusive by nature which will go against the ethos of democracy.[4]

Effects

"E-democracy offers greater electronic community access to political processes and policy choices. E-democracy development is connected to complex internal factors, such as political norms and citizen pressures"[8] and in general to the particular model of democracy implemented.[14] E-democracy is therefore highly influenced by both internal factors to a country and by the external factors of standard innovation and diffusion theory.[8] People are pressuring their public officials to adopt more policies that other states or countries have regarding information and news about their government online. People have all governmental information at their fingertips and easy access to contact their government officials. In this new generation where internet and networking rule everyone's daily lives, it is more convenient that people can be informed of the government and policies through this form of communication.

E-democracy has, in fact, endorsed a better and faster political information exchange, public argumentation and involvement in decision-making (Djik, 2006, pp. 126[15]). Social media has become an empowerment tool, especially for the youth, who are encouraged to participate in elections. Social media has also allowed the politicians to interact with civilians. A clear example was the 2016 American elections and how Donald Trump tweeted most of his announcements and goals. Not only Trump, but other presidents have Twitter accounts such as Justin Trudeau, Jair Bolsonaro, and Hassan Rouhani. Moreover, some people genuinely believe that the government posting public information online makes them more vulnerable and therefore more evident in people’s eyes, which favors the public’s surveillance. Thus, distributing power among society.[16]

In Jane Fountain's (2001) Building the Virtual State, she describes how this widespread e-democracy is able to connect with so many people and correlates it to the government we had before.

Fountain's framework provides a subtle and nuanced appreciation of the interplay of preexisting norms, procedures, and rules within bureaucracies and how these affect the introduction of new technological forms... In its most radical guise, this form of e- government would entail a radical overhaul of the modern administrative state as regular electronic consultations involving elected politicians, civil servants, pressure groups, and other affected interests become standard practice in all stages of the policy process (Sage).

Cities in states with Republican-controlled legislatures, high legislative professionalization, and more active professional networks were more likely to embrace e-government and e-democracy.[17]

Occupy movement

Following the financial crisis of 2007–08 a number of social networks proposed demonstrations such as the Occupy movement.[18]

15-M movement

The 15-M Movement started in Spain and spread to other European countries. From that emerged the Partido X (X Party) proposals in Spain.[19][20]

Arab Spring

During the "Arab Spring," online activists led uprisings in a dozen countries across North Africa and the Middle East. At first, digital media allowed pro-democracy movements to use the internet against authoritarian regimes; however, these regimes eventually worked social media into their own counter-insurgency strategies. Digital media helped to turn individualized, localized, and community-specific dissent into structured movements with a collective consciousness about both shared grievances and opportunities for action.[21]

Egyptian Revolution

On January 25 of 2011, mass protests began in Cairo, Egypt, protesting the long reign of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, the high unemployment rate, government corruption, poverty, and oppression within society. This 18-day revolution did not begin with guns, violence, or protests, but rather with the creation of a single Facebook page which quickly gained the attention of thousands, and soon millions, of Egyptians, spreading into a global phenomenon.[22] The internet empowered protesters and allowed for anyone with access to the internet be involved in the democratization process of their government. In order to have a democratic, free nation, all information that can be shared, should be shared. Protestors communicated, organized, and collaborated through the use of this technology with real time, real impacts.[23] Technologies played an enormous role on the world stage during this time. Even when the regime eliminated all access to the Internet in a failed attempt to halt further political online forums, Google and Twitter teamed up, making a system that would get information out to the public without having access to the internet.[24] The interactivity of media during this revolution boosted civic participation and played a monumental role in the political outcome of the revolution and the democratization of an entire nation.

The revolution in Egypt has been understood by some as an example of a broader trend of transforming from a system based on group control to one of "networked individualism". These networked societies are constructed post -"triple revolution" of technology, which involves a three-step process. Step one in the "triple revolution" is "the turn to social networks", step two: "the proliferation of the far-flung, instantaneous internet", and step three: "the even wider proliferation of always-available mobile phones".[25] These elements play a key role in change through the Internet. Such technologies provide an alternative sphere that is unregulated by the government, and where construction of ideas and protests can foster without regulation. For example, In Egypt, the "April 6 Youth Movement" established their political group on Facebook where they called for a national strike to occur on April 6. This event was ultimately suppressed, however; the Facebook group remained, spurring the growth of other activist parties to take an online media route. The Internet in Egypt was used also to form connections with networks of people outside of their own country. The connections provided through Internet media sources, such as Twitter allowed rapid spread of the revolt to be known around the world. Specifically, more than 3 million tweets contained six popular hashtags alluring to the revolt, for example, #Egypt and #sidibouzid; further enabling the spread of knowledge and change in Egypt.[25]

Kony 2012

The Invisible Children's Kony 2012 video was released March 5, 2012, initiating an online grassroots campaign for the search and arrest of Joseph Kony. Invisible Children, the non-profit organization responsible for this video campaign, was founded on the mission to bring awareness to the vile actions of the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA), located in Central Africa, and the arrest of its leader, Joseph Kony. In the video, Jason Russell, one of the founders of Invisible Children, says that "the problem is that 99% of the planet doesn't know who [Kony] is" and the only way to stop him is by having enough support from the people to convince the government to continue the hunt for him.[26] So, Invisible Children's purpose for the video was to raise awareness by making Kony famous through the ever-expanding market of social media and to use the technology we have today to bring his crimes to light.

On March 21, 2012, a group of 33 Senators introduced a resolution condemning "the crimes against humanity" committed by Joseph Kony and the LRA. The resolution supports the continued efforts by the US government to "strengthen the capabilities of regional military forces deployed to protect civilians and pursue commanders of the LRA, and calls for cross-border efforts to increase civilian protection and provide assistance to populations affected by the LRA." Senator Lindsey Graham, a co-sponsor of the resolution stated that "When you get 100 million Americans looking at something, you will get our attention. This YouTube sensation is gonna help the Congress be more aggressive and will do more to lead to his demise than all other action combined".[27]

India Against Corruption 2011-12

India Against Corruption (IAC) is an anti-corruption movement in India which was particularly prominent during the anti-corruption protests of 2011 and 2012, the central point of which was debate concerning the introduction of a Jan Lokpal bill. During that time it sought to mobilize the masses in support of their demands for a less corrupt society in India. Divisions amongst key members of the IAC's core committee eventually led to a split within the movement. Arvind Kejriwal left to form the Aam Aadmi Party, while Anna Hazare left to form Jantantra Morcha.

Long March (Pakistan)

In December 2012, after living for seven years in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, Qadri returned to Pakistan and initiated a political campaign. Qadri called for a "million-men" march in Islamabad to protest against the government's corruption.[28] On 14 January 2013, a crowd marched down the city's main avenue. Thousands of people pledged to sit-in until their demands were met.[29] When he started the long march from Lahore about 25,000 people were with him.[30] He told the rally in front of parliament: "There is no Parliament; there is a group of looters, thieves and dacoits [bandits] ... Our lawmakers are the lawbreakers.".[31] After four days of sit-in, the Government and Qadri signed an agreement called the Islamabad Long March Declaration, which promised electoral reforms and increased political transparency.[32] Although Qadri called for a "million-men" march, the estimated total present for the sit-in in Islamabad was 50,000 according to the government.

Five Star Movement (Italy)

In 2012, the rising Five Star Movement (M5S), in Italy, chose its candidates to Italian and European elections through online voting by registered members of Beppe Grillo's blog. Through an application called Rousseau reachable on the web,[33] the registered users of M5S discuss, approve or reject legislative proposals (submitted then in the Parliament by the M5S group).[34] For example, the M5S electoral law was shaped through a series of online votes,[35] like the name of the M5S candidate for President of the Republic in Italy.[36] The choice to support the abolition of a law against immigrants was taken online by members of the M5S even if the final decision was against the opinions of Grillo and Casaleggio.[37] The partnership with the UK Independence Party was also decided by online voting, although the given options for the choice of European Parliament group for M5S were limited to Europe of Freedom and Democracy (EFD), European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) and "Stay independent" (Non-Inscrits). The option of joining the Greens/EFA group was discussed, but this option was not available at the time of the voting due to that group's prior rejection of the M5S.[38][39] When the Conte I Cabinet broke down, a new coalition between Democratic Party and MS5 was approved after 100,000 members voted, with 79.3% approving the new coalition.[40]

Requirements

E-Democracy is made possible through its role in relevancy of participation, the social construction of inclusiveness, sensitivity to the individual, and flexibility in participation. The Internet provides a sense of relevancy in participation through allowing everyone's voice to be heard and expressed. A structure of social inclusion is also provided through a wide variety of Internet sites, groups, and social networks, all representing different viewpoints and ideas. Sensitivity to the individual's needs is accomplished through the ability to express individual opinions publicly and rapidly. Finally, the Internet is an extremely flexible area of participation; it is low in cost and widely available to the public. Through these four directions, E-Democracy and the implementation of the Internet are able to play an active role in societal change.[41]

Internet access

The E-democratic process is hindered by the digital divide between active participants and those who do not participate in electronic communities. Advocates of E-democracy may advocate government moves to close this gap.[42] The disparity e-governance and e-democracy between developed and developing worlds has been attributed to the digital divide.[43] Practical objections include the digital divide between those with access and those without, as well as the opportunity cost of expenditure on e-democracy innovations. There is also skepticism of the amount of impact that they can make through online participation.[44]

Security and the protection of privacy

The government must be in a position to guarantee that online communications are secure and that they do not violate people's privacy. This is especially important when considering electronic voting. An electoral voting system is more complex than other electronic transaction systems and the authentication mechanisms employed must be able to prevent ballot rigging or the threat of rigging. This may include the use of smart cards that allow a voter's identity to be verified whilst at the same time ensuring the privacy of the vote cast. Electronic voting in Estonia is one example of a method to conquer the privacy-identity problem inherent in internet voting systems. However, the objective should be to provide equivalence with the security and privacy of current manual systems.

Government responsiveness

In order to attract people to get involved in online consultations and discussions, the government must respond to people and actively demonstrate that there is a relationship between the citizen's engagement and policy outcome. It is also important that people are able to become involved in the process, at a time and place that is convenient to them but when their opinions will count. The government will need to ensure that the structures are in place to deal with increased participation.

In order to ensure that issues are debated in a democratic, inclusive, tolerant and productive way, the role that intermediaries and representative organizations may play should be considered. In order to strengthen the effectiveness of the existing legal rights of access to information held by public authorities, citizens should have the right to effective public deliberation and moderation.[45]

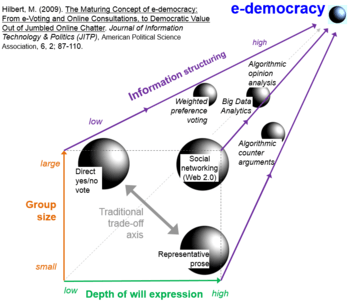

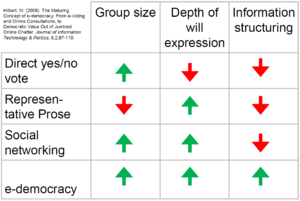

Types of interaction

E-democracy has the potential to overcome the traditional trade-off between the size of the group that participates in the democratic process and the depth of the will expression (see Figure). Traditionally, large group size was achieved with simple ballot voting, whereas the depth of the will expression was limited to predefined options (what's on the ballot), while depth of will expression was achieved by limiting the number of participants through representative democracy (see Table). The social media Web 2.0 revolution has shown to achieve both, large group sizes and depth of will expression, but the will expressions in social media are not structured and it is difficult (and often subjective) to make sense of them (see Table). New information processing techniques, including big data analytics and the semantic web have shown ways to make use of these possibilities for the implementation of future forms of e-democracy.[46] For now, the process of e-democracy is carried out by technologies such as electronic mailing lists, peer-to-peer networks, collaborative software and apps like GovernEye, Countable, VoteSpotter, wikis, Internet forums and blogs.

E-democracy has been analyzed with regard to the different stages of the democratic process, such as "information provision, deliberation, and participation in decision-making.",[47] by the hierarchical level of government, including local communities, states/regions, nations and on the global stage[48] and by its reach and scope of involvement, such as the involvement of citizens/voters, the media, elected officials, political organizations, and governments.[49] As such, "its development is conditioned by such pervasive changes as increased interdependency, technological multimediation, partnership governance, and individualism."[50]

Social media sites, such as Facebook, Twitter, WordPress and Blogspot, are playing an increasingly important role in democratic deliberations.[51][52] The role of social media in e-democracy has been an emerging area for e-democracy, as well as related technological developments, such as argument maps and eventually, the semantic web.[46] Another related development consists in combining the open communication of social networking with the structured communication of closed panels including experts and/or policy-makers, such as for example through modified versions of the Delphi method (HyperDelphi) to combine the open communication of self-organized virtual communities with the structured communication of closed panels, including members of the policy-community.[53][54] This approach addresses the question of how, in electronic democracy, to reconcile distributed knowledge and self-organized memories with critical control, responsibility and decision. The social networking entry point, for example, is within the citizens' environment, and the engagement is on the citizens' terms. Proponents of e-government perceive government use of social networks as a medium to help government act more like the public it serves. Examples of state usage can be found at The Official Commonwealth of Virginia Homepage,[55] where citizens can find Google tools and open social forums. Those are seen as important stepping stones in the maturation of the concept of e-democracy.[46]

Civic engagement

Civic engagement includes three dimensions: political knowledge of public affairs, political trust for the political system, and political participation in influencing the government and the decision-making process.[56] The internet aids civic engagement by providing a new avenue to interact with by governmental institutions.[57] Proponents of E-democracy believe that governments can be much more actively engaged than presently,[58] and encourage citizens to take their own initiative to influence decisions that will affect them.[59]

Many studies report increasing use of the internet to find political information. Between 1996 and 2002, the number of adults who reported that the internet was significant in their choices increased from about 14 to 20 percent.[60] In 2002, nearly a quarter of the population reported having visited a website to research specific public policy issues. Studies have shown that more people visit websites that challenge their point of view than visit websites that mirror their own opinions. Sixteen percent of the population has participated in online political culture by interacting with political websites through joining campaigns, volunteering time, donating money, or participating in polls. According to a survey conducted by Philip N. Howard, almost two-thirds of the adult population in the United States has had some online experience with political news, information, or other content over the past four election cycles.[60] They tend to reference the websites of special interest groups more than the websites of specific elected leaders, political candidates, political parties, nonpartisan groups, and local community groups.

The information capacity available on the Internet allows citizens to become more knowledgeable about government and political issues, and the interactivity of the medium allows for new forms of communication with government, i.e. elected officials and/or public servants. The posting of contact information, legislation, agendas, and policies makes government more transparent, potentially enabling more informed participation both online and offline.[61]

According to Matt Leighninger, the internet impacts government in two main ways, empowering individuals, and empowering groups of people.[62] The internet gives interested citizens better access to the information which allows them to impact on public policy. Using online tools to organize, people can more easily be involved in the policy-making process of government, and this has led to increased public engagement. Social media sites support networks of people; online networks affect the political process, including causing an increase in politicians' efforts to appeal to the public in campaigns.

For e-democracy provides a forum for public discussion. An e-government process improves cooperation with the local populace and helps the government focus in upon key issues the community wants addressed. The theory is that every citizen has the opportunity to have a voice in their local government. E-democracy works in tandem with local communities and gives every citizen who wants to contribute the chance. What makes an effective e-democracy is that the citizens not only contribute to the government, but they communicate and work together to improve their own local communities.[63]:397

E-democracy is the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) to support the democratic decision-making processes. ICTs play a major role in organizing and informing citizens in various forms of civic engagement. ICTs are used to enhance active participation of citizens and to support the collaboration between actors for policy-making purposes within the political processes of all stages of governance.[64][65]

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development lists three main factors when it comes to ICTs promoting civic engagement. The first of these is timing; most of the civil engagement occurs during the agenda-setting in a cycle. The second key factor is tailor; this refers to the idea of how ICTs are changing in order to allow for more civic engagement. The last of these factors is integrations; integration is how new ICTs are combining the new technological ways with the traditional ways in order to gain more civic engagement.[66]

ICT creates the opportunity for a government that is simultaneously more democratic and more expert by creating open online collaboration between professionals and the general public. The responsibility of gathering information and making decisions is shared between those with technological expertise and those who are professionally considered the decision-makers. Greater public participation in the collaboration of ideas and policies makes decision-making is more democratic. ICT also promotes the idea of pluralism within a democracy, bringing new issues and perspectives.[67]

Regular citizens become potential producers of political value and commentary, for example, by creating individual blogs and websites. The online political sphere can work together, like ABCNews did with their Campaign Watchdog effort, where citizens by the polls reported any rule violations perpetrated by any candidate's party.[68]

In 2000, Candidate's for the United States presidential race frequently used their websites to encourage their voters to not only vote, but to encourage their friends to vote as well. This two-step process, encouraging an individual to vote and to tell his or her friends to vote, was just emerging at that time. Now, political involvement from a variety of social media is commonplace and civic engagement through online forums frequent. Through the use of ICTs, politically minded individuals have the opportunity to become more involved.[68]

Youth engagement

Young people under the age of 35, or Generation X and Generation Y, have been noted for their lack of political interest and activity.[69] Electronic democracy has been suggested as a possible method to increase voter turnout, democratic participation, and political knowledge in youth.[70][71]

The notion of youth e-citizenship seems to be caught between two distinct approaches: management and autonomy. The policy of "targeting" young people so that they can "play their part" can be read either as an encouragement of youth activism or an attempt to manage it.[72] Autonomous e-citizens argue that despite their limited experience, youth deserve to speak for themselves on agendas of their own making. On the contrary, managed e-citizens regard young people as apprentice citizens who are in a process of transition from the immaturity of childhood to the self-possession of adulthood, and are thus incapable of contributing to politics without regulation. The Internet is another important issue, with managed e-citizens believing young people are highly vulnerable to misinformation and misdirection. The conflict between the two faces of e-citizenship is a view of democracy as an established and reasonably just system, with which young people should be encouraged to engage, and democracy as a political as well as cultural aspiration, most likely to be realized through networks in which young people engage with one another. Ultimately, strategies of accessing and influencing power are at the heart of what might first appear to be mere differences of communication styles.[72]

The Highland Youth Voice demonstrated the attempt to increase democratic involvement, especially through online measures, in Scotland.[73] The youth population is increasingly more prominent in governmental policy and issues in the UK. However, involvement and interest have been decreasing. In 2001 elections in the United Kingdom to Westminster, the turnout of 18- to 24-year-olds was estimated at only 40%, which can be compared to the more than 80% of 16- to 24-year-old who have accessed the internet at some time in their life.[74] The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child have promoted and stressed the need to educate the younger population as citizens of the nation in which they live in, and promote the participation and active politics which they can shape through debate and communication.

The Highland Youth Voice aims to increase the involvement of the younger generation through understanding their needs and wishes for their government, through an understanding of their views, experiences, and aspirations. Highland Youth Voice gives young Scots a chance to influence the decision makers in the Highlands.[73] The members age from 14 to 18 and the parliament as a whole is an elected body of around 100 members. They are elected directly through schools and youth forums. Through the website, those involved are able to discuss the issues important to them. The final prominent democratic aspect of the website is the elections for members, which occur every other year. These three contents of the website allow for an online forum in which members may educate themselves through Youth Voice, partake in online policy debates, or experience a model of e-democracy in the ease of online voting.

Civil society

Citizens' associations play an important role in the democratic process, providing a place for individuals to learn about public affairs and a source of power outside that of the state, according to theorists like Alexis de Tocqueville. Public policy researcher Hans Klein at the Georgia Institute of Technology notes that participation in such forums has a number of barriers, such as the need to meet in one place at one time.[75] In a study of a civic association in the northeastern United States, Klein found that electronic communications greatly enhanced the ability of the organization to fulfill its mission. The lower cost of information exchange on the Internet, as well as the high level of reach that the content potentially has, makes the Internet an attractive medium for political information, particularly amongst social interest groups and parties with lower budgets.

For example, environmental or social issue groups may find the Internet an easier mechanism to increase awareness of their issues, as compared to traditional media outlets, such as television or newspapers, which require heavy financial investment. Due to all these factors, the Internet has the potential to take over certain traditional media of political communication, such as the telephone, the television, newspapers and the radio. The civil society has gradually moved into the online world.[76]

There are many forms of association in civic society. The term interest group conventionally refers to more formal organizations that either focus on particular social groups and economic sectors, such as trade unions and business and professional associations, or on more specific issues, such as abortion, gun control, or the environment.[77] Other traditional interest groups have well-established organizational structures and formal membership rules, and their primary orientation is toward influencing government and the policy process. Transnational advocacy networks bring together loose coalitions of these organizations under common umbrella organizations that cross national borders.

Novel tools are being developed that are aimed at empowering bloggers, webmasters and owners of other social media, with the effect of moving from a strictly informational use of the Internet to using the Internet as a means of social organization not requiring top-down action. Calls to action, for instance, are a novel concept designed to allow webmasters to mobilize their viewers into action without the need for leadership. These tools are also utilized worldwide: for example, India is developing an effective blogosphere that allows internet users to state their thoughts and opinions.[78]

The Internet may serve multiple functions for all these organizations, including lobbying elected representatives, public officials, and policy elites; networking with related associations and organizations; mobilizing organizers, activists, and members using action alerts, newsletters, and emails; raising funds and recruiting supporters; and communicating their message to the public via the traditional news media.

Deliberative democracy

The Internet also plays a central role in deliberative democracy, where deliberation and access to multiple viewpoints is central in decision-making.[79] The Internet is able to provide an opportunity for interaction and serves as a prerequisite in the deliberative process as a research tool. On the Internet, the exchange of ideas is widely encouraged through a vast number of websites, blogs, and social networking outlets, such as Twitter; all of which encourage freedom of expression. Through the Internet, information is easily accessible, and in a cost-effective manner, providing access and means for change. Another fundamental feature of the Internet is its uncontrolled nature, and ability to provide all viewpoints no matter the accuracy. The freedom the Internet provides is able to foster and advocate change, crucial in E-Democracy.

A recent advancement in the utilization of E-Democracy for the deliberative process is the California Report Card created by the Data and Democracy Initiative of the Center for Information Technology Research in the Interest of Society[80] at University of California, Berkeley, together with Lt. Governor Gavin Newsom. The California Report Card, launched in January 2014, is a mobile-optimized web application designed to facilitate online deliberative democracy. After a short opinion poll on 6 timely issues, participants are invited to enter an online "café" where they are placed, using Principal Component Analysis, among users with similar views. They are then encouraged to engage in the deliberative process by entering textual suggestions about new political issues and grading other participants' suggestions. The California Report Card prides itself on being resistant to private agendas dominating the discussion.

Another example is openforum.com.au, an Australian non-profit eDemocracy project that invites politicians, senior public servants, academics, business people and other key stakeholders to engage in high-level policy debate.

An alternative to the SOPA and PIPA, the Online Protection and Enforcement of Digital Trade Act (OPEN Act) is supported by Google and Facebook. The OPEN Act website Keep The Web Open[81] provides full access to the bill. The site also incorporates user input, over 150 changes have been made by users.[82][83]

The peer-to-patent project allows the public to do research and present the patent examiner with 'prior art' publications which will inform them of the novelty of the invention so that they can determine whether the invention is worthy of a patent. The community elects ten prior art pieces to be sent to the patent examiner for review. This enables the public to directly communicate with the patent examiner. This form of e-democracy is a structured environment which demands certain information from participants that aid in the decision-making process. The goal of the project is to make decision-making process is made more effective by allowing experts and civilians who work together to find solutions. Beyond citizens checking a box that reduces opinions to a few given words, citizens can participate and share ideas.[84]

Voting and polling

Another great hurdle in implementing e-democracy is the matter of ensuring security in internet-voting systems. Viruses and malware could block or redirect citizens' votes on matters of great importance; as long as that threat remains, e-democracy will not be able to diffuse throughout society. Kevin Curran and Eric Nichols of the Internet Technologies Research Group noted in 2005 that "a secure Internet voting system is theoretically possible, but it would be the first secure networked application ever created in the history of computers".[85]

A lack of participation in democracy may result from a plethora of polls and surveys, which can lead to survey fatigue.[86]

Government transparency and accessibility

Through ListServs, RSS feeds, mobile messaging, micro-blogging services and blogs, government and its agencies can share information to citizens who share common interests and concerns. Some government representatives are also beginning to use Twitter which provides them with an easy medium to inform their followers. In the state of Rhode Island, for instance, Treasurer Frank T. Caprio is offering daily tweets of the state's cash flow.

A number of non-governmental sites have developed cross-jurisdiction, customer-focused applications that extract information from thousands of governmental organizations into a system that brings consistency to data across many dissimilar providers. It is convenient and cost-effective for businesses, and the public benefits by getting easy access to the most current information available without having to expend tax dollars to get it. One example of this is transparent.gov.com,[87] a free resource for citizens to quickly identify the various open government initiatives taking place in their community or in communities across the country. A similar example is USA.gov,[88] the official site of the United States government, which is a directory that links to every federal and state agency.

E-democracy leads to a more simplified process and access to government information for public-sector agencies and citizens. For example, the Indiana Bureau of Motor Vehicles simplified the process of certifying driver records to be admitted in county court proceedings. Indiana became the first state to allow government records to be digitally signed, legally certified and delivered electronically by using Electronic Postmark technology.[89]

The internet has created increased government accessibility to news, policies, and contacts in the 21st century: "In 2000 only two percent of government sites offered three or more services online; in 2007 that figure was 58 percent. In 2000, 78 percent of the states offered no on-line services; in 2007 only 14 percent were without these services (West, 2007)"(Issuu). Direct access via email has also increased; "In 2007, 89 percent of government sites allowed the public e-mail a public official directly rather than simply e-mailing the webmaster (West, 2007)"(Issuu).

Opposition

Information and communications technologies can be used for both democratic and anti-democratic ends.(e.g. both coercive control and participation can be fostered by digital technology)[14] George Orwell's in his Nineteen Eighty-Four is one example of the vision of the anti-democratic use of technology.

Objections to direct democracy are argued to apply to e-democracy, such as the potential for direct governance to tend towards the polarization of opinions, populism, and demagoguery.[14]

Internet censorship

In a nation with heavy government censorship, e-democracy could not be utilized to its full extent. Governments often implement internet crackdowns during widespread political protests. In the middle-east in 2011, for example, the multiple cases of internet blackouts were dubbed the "Arab Net Crackdown". Libya, Egypt, Bahrain, Syria, Iran, and Yemen are all countries whose leaders implemented complete censorship of the internet in response to the plethora of pro-democracy demonstrations in their respective nations.[90] These lockdowns were primarily put in place in order to prevent the leakage of cell phone videos that contained images of the violent government crackdown on protesters.[91]

Additionally, based on Joshua A. Tucker's critics of e-democracy, social media's malleability and receptiveness may allow political parties to manipulate it and implement political desires (Tucker et al., 2017).[92] Through it, authorities are able to spread authoritarianism, firstly by, intimidation; imposing fear on opposers, monitoring private conversations and even imprisoning one who dissents non-desirable opinion. Secondly, flooding; diverting and occupying services with pro-regime messages. Thirdly, detaining; interrupting signals which impedes access to information. Lastly, banning; forbidding globalized platforms and websites (Tucker et al., 2017).[92]

Concerns with populism

In a study conducted that interviewed elected officials in Austria's parliament, opinions were widely and strongly against e-democracy. They believed that the citizens were uninformed and that their only way of expressing their opinions should be to vote; sharing opinions and ideas was strictly the job of the elected.[93][8]

Alternatively, theories of epistemic democracy have indicated that more engagement of the populace has benefited the aggregation of knowledge and intelligence, and thus permitted democracies to track the truth better.

Stop Online Piracy Act

Many Internet users believed that Internet democracy was being attacked in the United States with the introduction of H.R. 3261, Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA), in the United States House of Representatives.[94][95] A Huffington Post Contributor noted that the best way to promote democracy, including keeping freedom of speech alive, is through defeating the Stop Online Piracy Act.[94] It is important to note that SOPA was postponed indefinitely after major protests arose, including by many popular websites such as Wikipedia, which launched a site blackout on January 18, 2012.[96] In India, a similar situation was noted at the end of 2011, when India's Communication and IT Minister Kapil Sibal suggested that offensive content may be privately "pre-screened" before being allowed on the Internet with no rules for redressal.[51] However, more recent news reports quote Sibal as saying that there would be no restrictions whatsoever on the use of the Internet.[97]

Government models

Representative democracy

The radical shift from representative government to internet-mediated direct democracy is not likely. However, proponents believe that a "hybrid model" that uses the internet to allow for greater government transparency and community participation in decision-making is on the horizon.[98] Committee selection, local town and city decisions, and otherwise people-centric decisions would be more easily facilitated. The principles of democracy are not changing so much as the tools used to uphold them. E-democracy would not be a means to implement direct democracy, but rather a tool to enable more participatory democracy as it exists now.[99]

Electronic direct democracy

Proponents of E-democracy sometimes envision a transition from a representative democracy to a direct democracy carried out through technological means, and see this transition as an end goal of e-democracy.[100] In an Electronic direct democracy (EDD) (also known as open source governance or collaborative e-democracy), the people are directly involved in the legislative function by electronic means. Citizens electronically vote on legislation, author new legislation, and recall representatives (if any representatives are preserved).

Technology for supporting EDD has been researched and developed at the Florida Institute of Technology,[101] where the technology is used with student organizations. Numerous other software development projects are underway,[102] along with many supporting and related projects.[103] Several of these projects are now collaborating on a cross-platform architecture, under the umbrella of the Metagovernment project.[104]

EDD as a system is not fully implemented in a political government anywhere in the world, although several initiatives are currently forming. Ross Perot was a prominent advocate of EDD when he advocated "electronic town halls" during his 1992 and 1996 Presidential campaigns in the United States. Switzerland, already partially governed by direct democracy, is making progress towards such a system.[105] Senator On-Line, an Australian political party established in 2007, proposes to institute an EDD system so that Australians can decide which way the senators vote on each and every bill.[106] A similar initiative was formed 2002 in Sweden where the party Direktdemokraterna, running for the Swedish parliament, offers its members the power to decide the actions of the party over all or some areas of decision, or to use a proxy with immediate recall for one or several areas.

The Direktdemokraterna party in Sweden advocates EDD.

Liquid democracy

Liquid democracy, or direct democracy with delegable proxy, would allow citizens to choose a proxy to vote on their behalf while retaining the right to cast their own vote on legislation. The voting and the appointment of proxies could be done electronically. Taking this further, the proxies could form proxy chains, in which if A appoints B and B appoints C, and neither A nor B vote on a proposed bill but C does, C's vote will count for all three of them. Citizens could also rank their proxies in order of preference, so that if their first choice proxy fails to vote, their vote can be cast by their second-choice proxy.

Wikidemocracy

One proposed form of e-democracy is "wikidemocracy", with a government legislature whose codex of laws was an editable wiki, like Wikipedia. In 2012, J Manuel Feliz-Teixeira said he believed the resources to implement wikidemocracy were available. He envisions a wiki-system in which there would be three wings of legislative, executive and judiciary roles for which every citizen could have a voice with free access to the wiki and a personal ID to continuously reform policies until the last day of December (when all votes would be counted).[107] Advantages to wikidemocracy include a no-cost system with the removal of elections, no need for parliament or representatives because citizens directly represent themselves, and ease of access to voice one's opinion. However, there are obstacles, uncertainties and disagreements. First, the digital divide and low quality of education can be deterrents to achieve the full potential of a wikidemocracy. Similarly, there is a diffusion of innovation in response to new technologies in which some people readily adopt novel ways and others at the opposite end of the spectrum reject them or are slow to adapt.[108] It is also uncertain how secure this type of democracy would be because we would have to trust that the system administrator would have a high level of integrity to protect the votes saved to the public domain. Lastly, Peter Levine agrees that wikidemocracy would increase discussion on political and moral issues, but he disagrees with Feliz-Teixeira who argues that wikidemocracy would remove the need for representatives and formal governmental structures.[109]

Wikidemocracy is also used to mean more limited instantiations of e-democracy, such as in Argentina in August 2011, where the polling records of the presidential election were made available to the public in online form, for vetting.[110] The term has also been used in a more general way to refer to the democratic values and environments offered by wikis.[111]

In 2011, some in Finland undertook an experiment in wikidemocracy by creating a "shadow government program" on the Internet, essentially a compilation of the political views and aspirations of various groups in Finland, on a wiki.[112]

See also

- Collaborative governance

- Collaborative e-democracy

- Demoex - Democracy Experiment

- Democratization of technology

- E2D International

- E-Government

- E-participation

- Electronic civil disobedience

- Electronic Democracy Party, a political party in Turkey

- Emergent democracy

- eRulemaking

- Hacktivism

- Internet activism

- Isocracy

- Media democracy

- Online consultation

- Online deliberation

- Online Party of Canada, a political party in Canada

- Open politics

- Open source governance

- ParoleWatch

- Participation

- Parliamentary informatics

- Party of Internet Democracy, a political party in Hungary

- Platform cooperative

- Public Whip

- Second Superpower

- Smart mob

- Spatial Citizenship

- Technocracy

- Technology and society

- TheyWorkForYou

- Index of Internet-related articles

- Outline of the Internet

- IserveU, a Canadian based online voting platform.

References

- Ann Macintosh (2004). "Characterizing E-Participation in Policy-Making" (PDF). 2004 International Conference on System Sciences. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- Hosein Jafarkarimi; Alex Sim; Robab Saadatdoost; Jee Mei Hee (January 2014). "The Impact of ICT on Reinforcing Citizens' Role in Government Decision Making" (PDF). International Journal of Emerging Technology and Advanced Engineering. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- "SHARIQUE HASSAN MANAZIR - Google Scholar Citations". scholar.google.co.in. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- "Why the UN's e-government survey in India needs to better understand the idea of digital inclusion". South Asia @ LSE. 5 March 2019. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- Zanella, A (2017). "Humans, humus, and universe". Appl. Soil Ecol. 123: 561–567. doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2017.07.009.

- Novak, T., & Hoffman, D. (1998). Bridging the Digital Divide: The Impact of Race on Computer Access and Internet Use. Nashville: Vanderbilt University.

- Robert Dahl (1989). Democracy and Its Critics. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300049381.

- Chung-pin Lee; Kaiju Chang; Frances Stokes Berry (9 May 2011). "Testing the Development and Diffusion of E-Government and E-Democracy: A Global Perspective". Public Administration Review. 71 (3): 444–454. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02228.x.

- Oral, Behçet(2008). "Computers & Education: The evaluation of the student teachers' attitudes toward the Internet and democracy." Dicle University, Volume 50, Issue 1: 437-445.

- Matt Leighninger (2 May 2012). "Citizenship And Governance In A Wild, Wired World: How Should Citizens And Public Managers Use Online Tools To Improve Democracy?". National Civic Review. 100 (2): 20–29. doi:10.1002/ncr.20056.

- "European Journal of Scientific Research". www.europeanjournalofscientificresearch.com. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- John Keane (27 March 2012). "The politics of disillusionment: can democracy survive?". The Conversation. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- Waugh, Paul (30 July 2015). "Tom Watson Interview: On Jeremy Corbyn, Tony Blair, Leveson, Digital Democracy; And How He Sleeps At Night". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- "Digital Processes and Democratic Theory". MartinHilbert.net. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- van Dijk, Jan A.G.M.; Hacker, Kenneth L. (30 May 2018). Van Dijk, Jan A.G.M; Hacker, Kenneth L (eds.). Internet and Democracy in the Network Society. doi:10.4324/9781351110716. ISBN 9781351110716.

- "How the internet is transforming democracy". The Independent. 12 December 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- Lee, Chung-pin; Chang, Kaiju; Berry, Frances Stokes (2011). "Testing the Development and Diffusion of E-Government and E-Democracy: A Global Perspective". Public Administration Review. 71 (3): 444–454. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02228.x. JSTOR 23017501.

- "The 'Occupy' Movement: Emerging Protest Forms and Contested Urban Spaces | The Urban Fringe". ced.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- "X Party / Partido X". Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- Doreen Carvajal (8 October 2013). "Former Swiss Bank Employee Advising Spanish Political Party in Tax Battle". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- "The Role of Digital Media", Philip N. Howard, Muzammil M. Hussain. Journal of Democracy, Volume 22, Number 3, July 2011.pp. 35-48 10.1353/jod.2011.0041 (Abstract)

- Harry Smith (13 February 2011). "Wael Ghonim and Egypt's New Age Revolution". CBS News- 60 Minutes. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- Helen A.S. Popkin (16 February 2011). "Power of Twitter, Facebook in Egypt Crucial, Says U.N. Rep". MSNBC Technology. Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- Cecilia Kang (31 January 2011). "Google, Twitter Team up for Egyptians to Send Tweets via Phone". The Washington Post- Post Tech. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- Zhuo, X.; Wellman, B.; Yu, J. (2011). "Egypt: The first internet revolt?" (PDF). Peace Magazine. pp. 6–10.

- Hazel Shaw (7 March 2012). "Kony 2012: History in the making?". The University Times. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- Scott Wong (22 March 2012). "Joseph Kony captures Congress' attention". Politico. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- "Pakistani city prepares for cleric's march". 3 News NZ. 14 January 2013. Archived from the original on 30 January 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- "Long march: Walking in the name of 'revolution'". 15 January 2013.

- "Pakistanis protest 'corrupt' government". 3 News NZ. 15 January 2013. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- Declan Walsh (15 January 2013). "Internal Forces Besiege Pakistan Ahead of Voting". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- Anita Joshua (17 January 2013). "Qadri's picketing ends with 'Long March Declaration'". The Hindu. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- "M5S Operating System". Sistemaoperativom5s.beppegrillo.it. Archived from the original on 24 June 2014. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- Deseriis, Marco. Direct Parliamentarianism: An Analysis of the Political Values Embedded in Rousseau, the ‘Operating System’ of the Five Star Movement. 9.

- "Ecco la legge elettorale del M5S preannunciata da Casaleggio". Europaquotidiano.it. 19 May 2014. Archived from the original on 19 June 2014. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- "Quirinarie di M5s, per Rodotà 4.677 voti". Ansa.it. 20 April 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- "Grillo, gli iscritti del M5S dicono no al reato di immigrazione clandestina". Corriere della Sera. 13 January 2014. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- Nielsen, Nikolaj. "EUobserver / Greens reject Beppe Grillo's offer to team up". EUobserver. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- "Alleanze Europarlamento, M5S esclude i Verdi dalle consultazioni: "Troppi veti"". ilfattoquotidiano.it/. 12 June 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- "Italian vote backs new government under PM Conte". 3 September 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- Anttiroiko, Ari-Veikko (2003). "Building strong e-democracy: the role of technology in developing democracy for the information age". Commun. ACM. 46 (9): 121–128. doi:10.1145/903893.903926.

- Helbig, Natalie; Ramon J. Gil-Garcia (3 December 2008). "Understand the complexity of electronic government: Implications from the digital divide literature" (PDF). Government Information Quarterly. pp. 89–97 [95]. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- "The Impact of The Global Digital Divide on The World". Korea IT Times. 9 August 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- Komito, L. (2007). "Community and inclusion: The impact of new communications technologies". Irish Journal of Sociology. 16 (2): 77–96. doi:10.1177/079160350701600205. hdl:10197/10192.

- Waller Livesey Edin (2001)

- Martin Hilbert (April 2009). "The Maturing Concept of E-Democracy: From E-Voting and Online Consultations to Democratic Value Out of Jumbled Online Chatter". Journal of Information Technology and Politics. 6 (2): 87–110. doi:10.1080/19331680802715242. free access to the article can be found here martinhilbert.net/e-democracyHilbertJITP.pdf

- Pautz, H. (2010). "The Internet, Political Participation and Election Turnout". German Politics & Society. 28 (3): 156–175. doi:10.3167/gps.2010.280309.

- "E-Democracy, E-Governance, and Public Net-Work by Steven Clift - Publicus.Net". publicus.net. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- Clift, S. (2004). E-Democracy Resource Links from Steven Clift - E-Government, E-Politics, E-Voting Links and more. Retrieved July 10, 2009, from Publicus.Ne-t Public Strategies for the Online World: Publicus.net

- Anttiroiko, Ari-Veikko (2003). "Building Strong E-Democracy—The Role of Technology in Developing Democracy for the Information Age". Communications of the ACM. 46 (9): 121–128. doi:10.1145/903893.903926.

- Madhavan, N. (25 December 2011). "Is Internet Democracy under Threat in India?". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- Is Facebook keeping you in a political bubble? http://news.sciencemag.org/social-sciences/2015/05/facebook-keeping-you-political-bubble

- Bolognini, Maurizio (2001). Democrazia elettronica (Electronic Democracy). Rome: Carocci. ISBN 978-88-430-2035-5.. A summary of Democrazia elettronica is also in Glenn, Jerome C.; Gordon, Theodore J., eds. (2009). The Millennium Project. Futures Research Methodology. New York: Amer Council for the United Nations. ISBN 978-0981894119., chap. 23.

- See; Hilbert, Miles; Othmer (2009). "Foresight tools for participative policy-making in inter-governmental processes in developing countries: Lessons learned from the eLAC Policy Priorities Delphi" (PDF). Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 76 (7): 880–896. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2009.01.001.

- "Virginia.gov - Home". virginia.gov. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- Norris, Pippa (2001). Digital divide: civic engagement, information poverty, and the internet worldwide. Cambridge New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521002233.

- Bakardjieva, Maria (March 2009). "Subactivism: lifeworld and politics in the age of the internet". The Information Society. 25 (2): 91–104. doi:10.1080/01972240802701627. S2CID 17972877.

- Caldow, Janet (2003). "E-democracy: putting down global roots" (PDF). www-01.ibm.com/industries/government/ieg. IBM Institute for Electronic Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- Whittaker, Jason (2004), "Cyberspace and the public sphere", in Whittaker, Jason (ed.), The cyberspace handbook, London New York: Routledge, pp. 257–275, ISBN 978-0415168366.

- Howard, Philip N. (January 2005). "Deep democracy, thin citizenship: the impact of digital media in political campaign strategy". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 597 (1): 153–170. doi:10.1177/0002716204270139.

- ENGAGE: creating e-government that supports commerce, collaboration, community and Commonwealth (PDF). Folsom, California: Center for Digital Government. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2010.

- Leighninger, Matt (Summer 2011). "Citizenship and governance in a wild, wired world: how should citizens and public managers use online tools to improve democracy?". National Civic Review. 100 (2): 20–29. doi:10.1002/ncr.20056.

- Saglie, Jo; Vabo, Signy Irene (December 2009). "Size and e-democracy: online participation in Norwegian local politics". Scandinavian Political Studies. 32 (4): 382–401. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9477.2009.00235.x.

- Kubicek, H., & Westholm, H. (2007).

- Macintoch, Ann (2006)

- OECD (2003). Promise and Problems of E-Democracy (PDF). Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. ISBN 9789264019485.

ICTs can enable greater citizen engagement in policy-making...

- Clarke, Amanda (2010). Social media: 4. Political uses and implications for representative democracy (PDF). Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Reference and Strategic Analysis Division, Parliamentary Information and Research Service. OCLC 927202545. 2010-10-E.

- Foot, Kirsten A.; Schneider, Steven M. (June 2002). "Online action in Campaign 2000: an exploratory analysis of the U.S. political web sphere". Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media. 46 (2): 222–244. doi:10.1207/s15506878jobem4602_4. S2CID 145178519. Pdf.

- Owen, D. (2006). The Internet and youth civic engagement in the United States. In S. Oates, D. Owen & R. K. Gibson (Eds.), The Internet and politics: Citizens, voters and activists. London: Routledge.

- Canadian Parties in Transition, 3rd Edition. Gagnon and Tanguay (eds). Chapter 20 - Essay by Milner

- Andrew, Alex M. (2008). "Cybernetics and E-Democracy". Kybernetes. 37 (7): 1066–1068. doi:10.1108/03684920810884414. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- Coleman, Stephen. "Doing IT for Themselves: Management versus Autonomy in Youth E-Citizenship." Civic Life Online: Learning How Digital Media Can Engage Youth. Edited by W. Lance Bennett. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008. 189–206. doi:10.1162/dmal.9780262524827.189

- "Highland Youth Parliament - Official Website". hyv.org.uk. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- Macintosh, Ann; Robson, Edmund; Smith, Ella; Whyte, Angus (February 2003). "Electronic Democracy and Young People". Social Science Computer Review. 21: 43–54. doi:10.1177/0894439302238970. S2CID 55829523.

- Klein, Hans (January 1999). "Tocqueville in Cyberspace: Using the Internet for Citizens Associations". The Information Society. 15 (4): 213–220. doi:10.1080/019722499128376.

- Jensen, M.; Danziger, J.; Venkatesh, A. (2007). "Jan). Civil society and cyber society: The role of the internet in community associations and democratic politics". Information Society. 23 (1): 39–50. doi:10.1080/01972240601057528. S2CID 2580550.

- Norris, P. (2001). Digital divide: Civic engagement, information poverty, and the Internet worldwide. Cambridge: University Press

- The road to e-democracy. (2008, February). The Economist, 386(8567), 15.

- Gimmler, A (2001). "Deliberative democracy, the public sphere, and the internet". Philosophy Social Criticism. 27 (4): 21–39. doi:10.1177/019145370102700402.

- "CITRIS - Ken Goldberg appointed Faculty Director of the CITRIS Data and Democracy Initiative". Archived from the original on 9 June 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- "keeping the internet open & delivering open government technology". keepthewebopen.com. Archived from the original on 17 September 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- Sutter, John D. (18 January 2012). "The OPEN Act as an experiment in digital democracy – What's Next - CNN.com Blogs". CNN Blogs. Archived from the original on 11 September 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- Sutter, John D (18 January 2012). "The OPEN Act as an experiment in digital democracy". whatsnext.blogs.cnn.com. CNN. Archived from the original on 22 January 2012. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- Beth Simone Noveck (2008). "Wiki-Government". Democracy Journal. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- Curran, Kevin; Nichols, Eric (2005). "E-Democracy". Journal of Social Sciences. 1 (1): 16–18. doi:10.3844/jssp.2005.16.18.

- Cloke, Paul J., ed. (2004). Practising Human Geography (reprint ed.). London: Sage. p. 130. ISBN 9780761973003. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

Questionnaire surveys are a familiar fact of life in the developed world. [...] This very familiarity has in turn led some people to develop their own responsive strategies, such as a polite but quick refusal to participate - perhaps a reflexive response of 'survey fatigue' to the intrusive nature of surveys in society.

- "Making Government User-friendly - Government Information". gov.com. Archived from the original on 3 June 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- "USA.gov: The U.S. Government's Official Web Portal". usa.gov. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- "BMV: myBMV". in.gov. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- "Corporations and the Arab Net Crackdown". Foreign Policy In Focus. 25 March 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- "SaveTheInternet.com - Egypt's Internet Crackdown". freepress.net. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- Tucker, Joshua A.; Theocharis, Yannis; Roberts, Margaret E.; Barberá, Pablo (2017). "From Liberation to Turmoil: Social Media And Democracy". Journal of Democracy. 28 (4): 46–59. doi:10.1353/jod.2017.0064. ISSN 1086-3214.

- Mahrer, Harold; Krimmer (January 2005). "Towards the enhancement of e-democracy: identifying the notion of the 'middleman paradox'". Information Systems Journal. 15 (1): 27–42. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2575.2005.00184.x. S2CID 16020005.

- Brian Fox (30 January 2012). "Protecting Internet Democracy". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- Smith, Congressman Lamar. "H.R. 3261." Ed. Representatives, House of. Washington, DC: 112th Congress, 1st Session, 2011. Print.

- Julianna Pepitone (24 September 2012). "Sopa and Pipa Postponed Indefinitely after Protests". CNN Money. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- "IT News Online > - Kapil Sibal: Internet an Indispensable Tool for Governance in a Free Democracy". itnewsonline.com. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- Anttiroiko, Ari-Veikko (September 2003). "Building Strong E-Democracy—The Role of Technology in Developing Democracy for the Information Age". Communications of the ACM. 46 (9): 121–128. doi:10.1145/903893.903926. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- Sendag, Serkan (2010). "Pre-service teachers' perceptions about e-democracy: A case in Turkey". Computers & Education. 55 (4): 1684–1693. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2010.07.012.

- Fuller, Roslyn (2015). Beasts and Gods: How Democracy Changed Its Meaning and Lost its Purpose. United Kingdom: Zed Books. p. 371. ISBN 9781783605422.

- Kattamuri, et al. "Supporting Debates Over Citizen Initiatives", Digital Government Conference, pp 279-280, 2005

- List of active projects Archived 28 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine involved in the Metagovernment project

- List of related projects Archived 28 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine from the Metagovernment project

- Standardization project Archived 7 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine of the Metagovernment project.

- "Electronic Voting in Switzerland". swissworld.org. Archived from the original on 7 April 2005.

- "Senator On-Line". Archived from the original on 7 June 2008. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- "Feliz-Teixeira, J Manuel. The Perfect Time for the Perfect Democracy? Some thoughts on wiki-law, wiki-government, online platforms in the direction of a true democracy. Porto, 11 March 2012" (PDF). Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- "Robinson, Les. A summary of Diffusion of Innovations. Fully revised and rewritten Jan. 2009. Enabling Change" (PDF). Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- "Democracy's Moment". peterlevine.ws. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ""Wiki" Democracy Begins In Argentina". The Huffington Post. 24 August 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- "GetWiki - The Messiness of WikiDemocracy". getwiki.net. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- "Santa's Little Helpers: Wikidemocracy in Finland - Ominvoimin – ihmisten tekemää". ominvoimin.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

External links

- Council of Europe's work on e-Democracy - Including the work of the Ad Hoc Committee on e-Democracy IWG established in 2006

- Edc.unigue.ch - Academic research centre on electronic democracy. Directed by Alexander H. Trechsel, e-DC is a joint-venture between the University of Geneva's c2d, the European University Institute in Florence and the Oxford University's OII.

- [ ICELE] - International Centre of Excellence for Local eDemocracy, a UK driven international project exploring tools, products, research and learning for local e-democracy.

- Institute for Politics Democracy and the Internet

- Democras

- [ Esri.salford.ac.uk], IPOL - A portal on Internet and politics — Website including primary and secondary research resources related to online participation, e-democracy and the use of the Internet by parliaments and assemblies; edited by Stephen Ward, Wainer Lusoli and Rachel Gibson.

- ICEGOV - International Conference on Electronic Governance

- nytimes.com

- - launched to elected local councillors across the UK in 2013 to enable them to work alongside local residents in the democratic determination of community priorities

- transparent-gov For more information.

- Balbis Platform for digital democracy which enables creation of proposals, debates and voting.

- The Blueprint of E-Democracy

- Open source platform for E-Democracy in India