Intergenerational equity

Intergenerational equity in economic, psychological, and sociological contexts, is the concept or idea of fairness or justice between generations. The concept can be applied to fairness in dynamics between children, youth, adults and seniors, in terms of treatment and interactions. It can also be applied to fairness between generations currently living and generations yet to be born.[1]

.jpeg)

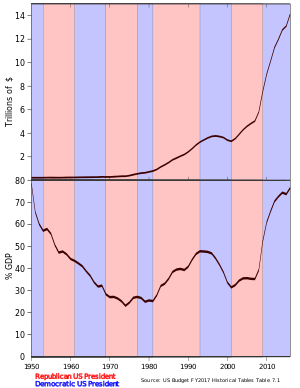

Conversations about intergenerational equity occur across several fields.[2] It is often discussed in public economics, especially with regard to transition economics,[3] social policy, and government budget-making.[4] Many cite the growing U.S. national debt as an example of intergenerational inequity, as future generations will shoulder the consequences. Intergenerational equity is also explored in environmental concerns,[5] including sustainable development,[6] global warming and climate change. The continued depletion of natural resources that has occurred in the past century will likely be a significant burden for future generations. Intergenerational equity is also discussed with regard to standards of living, with the focus falling on inequities in the living standards experienced by people of different ages and generations.[7][9] Intergenerational equity issues also arise in the arenas of elderly care and social justice.

Public economics usage

History

Since the first recorded debt issuance in Sumaria in 1796 BC,[10] one of the penalties for failure to repay a loan has been debt bondage. In some instances, this repayment of financial debt with labor included the debtor's children, essentially condemning the debtor family to perpetual slavery. About one millennium after written debt contracts were created, the concept of debt forgiveness appears in the Old Testament, called Jubilee (Leviticus 25), and in Greek law when Solon introduces Seisachtheia. Both of these historical examples of debt forgiveness involved freeing children from slavery caused by their parents' debt.

While slavery is illegal in all countries today, North Korea has a policy called, "Three Generations of Punishment"[11] which has been documented by Shin Dong-hyuk and used as a moral paragon of punishing children for parents' mistakes. Stanley Druckenmiller and Geoffrey Canada have applied this concept (calling it "Generational Theft"[12]) to the large increase in government debt being left by the Baby Boomers to their children.

Investment management

In the context of institutional investment management, intergenerational equity is the principle that an endowed institution's spending rate must not exceed its after-inflation rate of compound return, so that investment gains are spent equally on current and future constituents of the endowed assets. This concept was originally set out in 1974 by economist James Tobin, who wrote that, "The trustees of endowed institutions are the guardians of the future against the claims of the present. Their task in managing the endowment is to preserve equity among generations."[13] in terms of an economical context. Intergenerational equity refers to relationship that a particular family has on resources. An example is the forest-dwelling civilians in Papua New Guinea, who for generations have lived in a certain part of the forest which thus becomes their land. The adult population sell the trees for palm oil to make money. If they cannot make a sustainable development on managing their resources, their next or future generations will lose this resource.

U.S. national debt

One debate about the national debt relates to intergenerational equity. For example, if one generation is receiving the benefit of government programs or employment enabled by deficit spending and debt accumulation, to what extent does the resulting higher debt impose risks and costs on future generations? There are several factors to consider:

- For every dollar of debt held by the public, there is a government obligation (generally marketable Treasury securities) counted as an asset by investors. Future generations benefit to the extent these assets are passed on to them, which by definition must correspond to the level of debt passed on.[14]

- As of 2010, approximately 72% of the financial assets were held by the wealthiest 5% of the population.[15] This presents a wealth and income distribution question, as only a fraction of the people in future generations will receive principal or interest from investments related to the debt incurred today.

- To the extent the U.S. debt is owed to foreign investors (approximately half the "debt held by the public" during 2012), principal and interest are not directly received by U.S. heirs.[14]

- Higher debt levels imply higher interest payments, which create costs for future taxpayers (e.g., higher taxes, lower government benefits, higher inflation, or increased risk of fiscal crisis).[16]

- To the extent the borrowed funds are invested today to improve the long-term productivity of the economy and its workers, such as via useful infrastructure projects, future generations may benefit.[17]

- For every dollar of intragovernmental debt, there is an obligation to specific program recipients, generally non-marketable securities such as those held in the Social Security Trust Fund. Adjustments that reduce future deficits in these programs may also apply costs to future generations, via higher taxes or lower program spending.

Economist Paul Krugman wrote in March 2013 that by neglecting public investment and failing to create jobs, we are doing far more harm to future generations than merely passing along debt: "Fiscal policy is, indeed, a moral issue, and we should be ashamed of what we’re doing to the next generation's economic prospects. But our sin involves investing too little, not borrowing too much." Young workers face high unemployment and studies have shown their income may lag throughout their careers as a result. Teacher jobs have been cut, which could affect the quality of education and competitiveness of younger Americans.[18]

Australian politician Christine Milne made similar statements in the lead up to the 2014 Carbon Price Repeal Bill, naming the Liberal National Party (elected to parliament in 2013) and inherently its ministers, as intergenerational thieves; her statement was based on the party's attempts to roll back progressive carbon tax policy and the impact this would have on the intergenerational equity of future generations.

U.S. Social Security

The U.S. Social Security system has provided a greater net benefit to those who reached retirement closest to the first implementation of the system. The system is unfunded, meaning the elderly who retired right after the implementation of the system did not pay any taxes into the social security system, but reaped the benefits. Professor Michael Doran estimates that cohorts born previous to 1938 will receive more in benefits than they pay in taxes, while the reverse is true to cohorts born after. Further, he admits that the long-term insolvency of Social Security will likely lead to be further unintentional intergenerational transfers.[19] However, Broad concedes that other benefits have been introduced into U.S. society via the welfare system, like Medicare and government-financed medical research, that benefit current and future elderly cohorts.[19]

Environmental usage

.jpg)

Intergenerational equity is often referred to in environmental contexts, as younger age cohorts will disproportionately experience the negative consequences of environmental damage. Two perspectives can be taken on what should be done to ameliorate environmental intergenerational equity: the "weak sustainability" perspective and the "strong sustainability" perspective. From the "weak" perspective, intergenerational equity would be achieved if losses to the environment that future generations face were offset by gains in economic progress. From the "strong" perspective, no amount of economic progress can justify leaving future generations with a degraded environment. According to Professor Sharon Beder, the "weak" perspective is undermined by a lack of knowledge of the future, as we do not know which intrinsically valuable resources will not be able to be replaced by technology.[20] We also do not know to what extent environmental damage is irreversible. Further, more harm cannot be avoided to many species of plants and animals.[20] Other scholars contest Beder's point of view. Professor Wilfred Beckerman insists that "strong sustainability" is "morally repugnant", particularly when it overrides other moral concerns about those alive today.[21] Beckerman insists that the optimal choice for society is to prioritize the welfare of current generations above future generations. He suggests placing a discount rate on outcomes for future generations when accounting for generational equity.[21] Beckerman is extensively criticized by Brian Barry[22] and Nicholas Vrousalis.[23]

climate-related lawsuit

In September 2015, a group of youth environmental activists filed to sue the U.S. federal government for insufficiently protecting against climate change, the lawsuit is known as Juliana v. United States. Their statement emphasized the disproportionate cost of climate-related damage younger generations would bear.[24] It stated “Youth Plaintiffs represent the youngest living generation, beneficiaries of the public trust. Youth Plaintiffs have a substantial, direct, and immediate interest in protecting the atmosphere, other vital natural resources, their quality of life, their property interests, and their liberties. They also have an interest in ensuring that the climate system remains stable enough to secure their constitutional rights to life, liberty, and property, rights that depend on a livable Future.”[25] In November 2016, the case was allowed to go to trial after US District Court Judge Ann Aiken denied the federal government’s motion to dismiss the case. In her opinion and order, she said, “Exercising my ‘reasoned judgment,’ I have no doubt that the right to a climate system capable of sustaining human life is fundamental to a free and ordered society."[26] As of April 2017, the trial was put on hold with a stay. The Ninth Circuit heard oral arguments on the stay in November of 2017 and a ruling is expected in February of 2018.

Standards of living usage

Discussions of intergenerational equity in standards of living have referenced differences between people of different ages as well as differences between people of different generations. Two perspectives on intergenerational equity in living standards have been distinguished by Rice, Temple and McDonald. The first perspective – a "cross-sectional" perspective – focuses on living standards at a particular point in time and how these living standards vary between people of different ages. The relevant issue is the degree to which, at a particular point in time, people of different ages enjoy equal living standards. The second perspective – a "cohort" perspective – focuses on living standards over a lifetime and how these living standards vary between people of different generations. For intergenerational equity, the relevant issue becomes the degree to which people of different generations enjoy equal living standards over their lifetimes.[9] Three indicators of intergenerational equity in economic flows, such as income, have been proposed by D'Albis, Badji, El Mekkaoui and Navaux. Their first indicator originates from a cross-sectional perspective and describes the relative situation of an age group (retirees) with respect to the situation of another age group (younger people). Their second indicator originates from a cohort perspective and compares the standards of living of successive generations at the same age. D'Albis, Badji, El Mekkaoui and Navaux's third indicator is a combination of the two previous criteria and is both an inter-age indicator and an intergenerational indicator.

In Australia, notable equality has been achieved in living standards, as measured by consumption, among people between the ages of 20 and 75 years. Substantial inequalities exist, however, between different generations, with older generations experiencing lower living standards in real terms at particular ages than younger generations. One way to illustrate these inequalities is to look at how long different generations took to achieve a level of consumption of $30,000 per year (2009-10 Australian dollars). At one extreme, people born in 1935 achieved this level of consumption when they were roughly 50 years of age, on average. At the other extreme, Millennials born in 1995 had achieved this level of consumption by the time they were around 10 years of age.[9]

Considerations such as this have led some scholars to argue that standards of living have tended to increase generation over generation in most countries, as development and technology have progressed. When taking this into account, younger generations may have inherent privileges over older generations, which may offset the redistribution of wealth towards older generations.[27]

Elderly care usage

Some scholars consider the changing cultural trends that move society away from the norm of adult children caring for elderly parents to be an intergenerational equity issue. The older generation had to care for their parents, as well as their own children, while the younger generation must only care for their children. This is especially true in countries with weak social security systems. Professor Sang-Hyop Lee describes the presence of this phenomenon in South Korea, explaining that the current elderly now have the highest poverty rate among any developed country. He notes that it is particularly frustrating because the elderly usually invest a lot in their children's education, and they now feel betrayed.[28]

Other scholars express different opinions on which generation is truly disadvantaged by elderly care. Professor Steven Wisensale describes the burden on current working age adults in developed economies, who must care for more elderly parents and relatives for a longer period of time. This problem is exacerbated by the increasing involvement of women in the workforce, and by the dropping fertility rate, leaving the burden for caring for parents, as well as aunts, uncles, and grandparents, on fewer children.[29]

Social justice usage

Conversations about intergenerational equity are also relevant to social justice arenas as well, where issues such as health care[30] are equal in importance to youth rights and youth voice are pressing and urgent. There is a strong interest within the legal community towards the application of intergenerational equity in law.[31]

Advocacy groups

Generation Squeeze is a Canadian not-for-profit organization that advocates for intergenerational equity.

See also

- Adultism

- Ageism

- Environmental ethics

- Ephebiphobia

- Evolving capacities

- Generation Squeeze

- Generational accounting

- Gerontocracy

- Gerontophobia

- Inter-generational contract

- Justice (economics)

- Pedophobia

- Transgenerational design

- Weak and strong sustainability

- Youth rights

- Youth-adult partnerships

References

- "The Big Read: Generation wars". Herald Scotland. August 5, 2017.

- (n.d.) EPE Values: Intergenerational Ethics Archived 2010-07-03 at the Wayback Machine Earth and Peace Education Associates International website.

- (2005) "Economics of Intergenerational Equity in Transition Economies" Archived 2011-10-02 at the Wayback Machine 10–11 March 2005.

- Thompson, J. (2003) Research Paper no. 7 2002-03 Intergenerational Equity: Issues of Principle in the Allocation of Social Resources Between this Generation and the Next. Social Policy Group for the Parliament of Australia.

- Gosseries, A. (2008) "Theories of intergenerational justice: a synopsis". S.A.P.I.EN.S. 1 (1)

- (2005) Understanding Sustainable Development Archived 2012-05-24 at the Wayback Machine Cambridge University Press.

- d'Albis, Hippolyte and Ikpidi Badji (2017) "Intergenerational Inequalities in Standards of Living in France", Economie et Statistique / Economics and Statistics, 491-492: 71-92.

- Rice, James M, Jeromey B Temple and Peter F McDonald (2017) "Private and Public Consumption across Generations in Australia", Australasian Journal on Ageing, 36(4): 279–285.

- Goetzmann, William. "Financing Civilization". viking.som.yale.edu. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- Kaechon internment camp

- "WSJ". Retrieved 14 April 2018 – via online.wsj.com.

- Tobin, James. (1974) "What is Permanent Endowment Income?"

- "Debt Is (Mostly) Money We Owe to Ourselves". nytimes.com. 28 December 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- "Who Rules America: Wealth, Income, and Power". www2.ucsc.edu. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- Huntley, Jonathan (July 27, 2010). "Federal debt and the risk of a fiscal crisis". Congressional Budget Office: Macroeconomic Analysis Division. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- Baker, Dean. "David Brooks Is Projecting His Self Indulgence Again". cepr.net. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- Krugman, Paul (28 March 2013). "Opinion - Cheating Our Children". Retrieved 14 April 2018 – via NYTimes.com.

- Michael Doran (2008). “Intergenerational Equity in Fiscal Policy Reform”. Tax law Rewiew. 61: 241-293

- Sharon Beder, 'Costing the Earth: Equity, Sustainable Development and Environmental Economics', New Zealand Journal of Environmental Law, 4, 2000, pp. 227-243.

- Beckerman, Wilfred. "'Sustainable Development': Is it a Useful Concept?" Environmental Values 3, no. 3, (1994): 191–209. doi:10.3197/096327194776679700.

- Brian Barry, 'Sustainability and Integenerational Justice', in Dobson (1999) (Ed) Fairness and Futurity.

- Nicholas Vrousalis, 'Integenerational Justice: A Primer', Institutions for Future Generations, Gosseries, A. & I. Gonzalez (eds.), Oxford University Press 2016, pp. 49-64.

- Chemerinsky, Erwin (July 11, 2016). "Citizens Have a Right to Sue for Climate Change Action". New York Times. Retrieved April 28, 2017.

- Juliana V. United States, First Amended Complaint for Declaratory and Injunctive Relief United States District Court, District of Oregon - Eugene Division Filed 9/10/15

- Juliana V United States, Opinion and Order In the United States District Court for the District of Oregon Eugene Division Issued 11/10/16

- Gruber, Jonathan (2016). Public Finance and Public Policy Fifth Edition (c) 2016. Massachusetts, United States: Massachusetts Institute of Technology. ISBN 978-0716786559.

- Willian, Caroline (March 27, 2017). "Sang-Hyop Lee on the middle-income trap and demographic crisis in East Asia". Asia Experts Forum.

- Steven K. Wisensale PhD (2005) Aging Societies and Intergenerational Equity Issues, Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 17:3-4, 79-103, doi: 10.1300/J086v17n03_05

- Williams, A. (1997) "Intergenerational equity: An exploration of the 'fair innings' argument." Health Economics. 6(2):117-32.

- O'Brein, M. (n.d.) Not, 'Is it Irreparable?' But, 'Is it Unnecessary?' Thoughts on a Practical Limit for Intergenerational Equity Suits. Eugene, OR: Constitutional Law Foundation.

Further reading

- Bishop, R (1978) "Endangered Species and Uncertainty: The Economics of a Safe Minimum Standard", American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 60 p10-18.

- Brown-Weiss, E (1989) In Fairness to Future Generations: International Law, Common Patrimony and Intergenerational Equity. Dobbs Ferry, NY: Transitional Publishers, Inc., for the United Nations University, Tokyo.

- Daly, H. (1977) Steady State Economics: The Economics of Biophysiscal Equilibrium and Moral Growth. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman and Co.

- Frischmann, B. (2005) "Some Thoughts on Shortsightedness and Intergenerational Equity", Loyola University Chicago Law Journal, 36.

- Goldberg, M (1989) On Systemic Balance: Flexibility and Stability In Social, Economic, and Environmental Systems. New York: Praeger.

- Howarth, R. & Norgaard, R.B. (1990) "Intergenerational Resource Rights, Efficiency, and Social Optimality", Land Economics, 66(1) p1-11.

- Laslett, P. & Fishkin, J. (1992) Justice Between Age Groups and Generations. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Portney, P. & Weyant, J. P. (1999) Discounting and Intergenerational Equity. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future Press.

- McLean, D. "Intergenerational Equity" in White, J. (Ed) (1999) Clobal Climate Change: Linking Energy, Environment, Economy, and Equity. Plenum Press.

- Sikora, R.I. & Barry, B. (1978) Obligations to Future Generations. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

- Tabellini, G. (1991) "The Politics of Intergenerational Redistribution", Journal of Political Economy, 99(2) p335-358.

- Thompson, Dennis F. (2011) "Representing Future Generations: Political Presentism and Democratic Trusteeship," in Democracy, Equality, and Justice, eds. Matt Matravers and Lukas Meyer, pp. 17–37. ISBN 978-0-415-59292-5

- Vrousalis, N. (2016). "Intergenerational Justice: A Primer". in Gosseries and Gonzalez (2016) (eds). Institutions for Future Generations. Oxford University Press, 49-64

- Wiess-Brown, Margaret. "Chapter 12. Intergenerational equity: a legal framework for global environmental change" in Wiess-Brown, M. (1992) Environmental change and international law: New challenges and dimensions. United Nations University Press.

- Willetts, D. (2010). The pinch: How the baby boomers took their children's future and why they should give it back. London: Atlantic Books.