Gongche notation

Gongche notation or gongchepu is a traditional musical notation method, once popular in ancient China. It uses Chinese characters to represent musical notes. It was named after two of the Chinese characters that were used to represent musical notes, namely "工" gōng and "尺" chě. Since the pronunciation chě for the character "尺" is uncommon, many people call it gongchi notation or gongchipu by mistake.

| Gongche notation | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 工尺譜 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 工尺谱 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Sheet music written in this notation is still used for traditional Chinese musical instruments and Chinese operas. However the notation is becoming less popular, replaced by mostly jianpu (numbered musical notation) and sometimes the standard western notation.

The notes

Basic characters

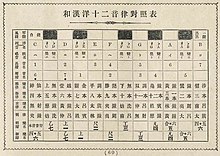

The notation usually uses a movable "do" system. There are variations of the character set used for musical notes. A commonly accepted set is shown below with its relation to jianpu and solfege.

Gongche 上

shàng尺

chě工

gōng凡

fán六

liù五

wǔ乙

yǐJianpu 1 2 3 (4) 5 6 (7) Movable do solfège syllable do re mi (between fa and fa♯) sol la (between ti♭ and ti) Simplified Japanese notation ル 人 フ り 久 ゐ

Usual variations

The three notes just below the central octave are usually represented by special characters:

Gongche 合

hé四

sì一

yīJianpu 5̣ 6̣ (7̣) Solfege sol la (between ti♭ and ti) Simplified Japanese notation ㄙ マ ㄧ

Sometimes "士" shì is used instead of "四" sì. Sometimes "一" yī is not used, or its role is exchanged with "乙" yǐ.

To represent other notes in different octaves, traditions differ among themselves. For Kunqu, the end strokes of "上" "尺" "工" "凡" are extended by a tiny slash downward for the lower octave, a radical "亻" is added for one octave higher than the central. For Cantonese opera, however, "亻" means an octave lower, while "彳" means an octave higher.

Some other variations:

- "尺" is replaced by "乂" in Taiwanese tradition.

- "凡" is replaced by "反" in Cantonese tradition.

- "彳上", the "do" just above the central octave, is usually replaced by "生" in Cantonese tradition.

The following are two examples.

Gongche scale for Kunqu Gongche 上̗ 尺̗ 工̗ 凡̗ 合 四 一 上 尺 工 凡 六 五 乙 仩 伬 仜 𠆩 𠆾 伍 亿 Jianpu 1̣ 2̣ 3̣ 4̣ 5̣ 6̣ 7̣ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1̇ 2̇ 3̇ 4̇ 5̇ 6̇ 7̇ Solfege do re mi fa sol la ti do re mi fa sol la ti do re mi fa sol la ti

Gongche scale for Cantonese opera Gongche 佮 仕 亿 仩 伬 仜 仮 合 士 乙 上 尺 工 反 六 五 𢒼 生 鿈 𢓁 𢓉 Jianpu 5̣̣ 6̣̣ 7̣̣ 1̣ 2̣ 3̣ 4̣ 5̣ 6̣ 7̣ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1̇ 2̇ 3̇ 4̇ Solfege sol la ti do re mi fa sol la ti do re mi fa sol la ti do re mi fa

Pronunciation

When the notes are sung in different opera traditions, they do not sound as the words would be pronounced in the respective regional dialects. Instead, they are pronounced in an approximation of Modern Standard Chinese pronunciation.

The following is an example from Cantonese opera.

Pronunciation of Cantonese Gongche characters Gongche

character合 士 乙 上 尺 工 反 六 五 Cantonese Gongche

pronunciation[hɔ̏ː] [sìː] [jìː] [sɑ̄ːŋ] [tsʰɛ́ː] [kʊ́ŋ] [fɑ́ːn] [líːu] [wúː] Usual Cantonese

pronunciation[hɐ̀p] [sìː] [jỳːt] [sœ̀ːŋ] [tsʰɛ̄ːk] [kʊ́ŋ] [fɑ̌ːn] [lʊ̀k] [ŋ̬̍]

Rhythm

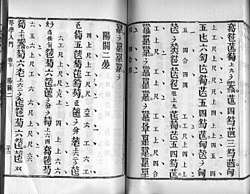

Gongche notation does not mark the relative length of the notes. Instead, marks for the percussion, understood to be played at regular intervals, are written alongside the notes. Gongche is written in the same format as Chinese was traditionally written; from top to bottom and then from right to left. The rhythm marks are written to the right of the note characters.

The diagram at the left illustrates how the tune "Old McDonald Had a Farm" will look like if written in gongche notation. Here, "。" denotes the stronger beat, called "板" bǎn or "拍" pāi, and "、" denotes the weaker beat, called "眼" yǎn or "撩" liáo. In effect, there is one beat in every two notes, i.e. two notes are sung or played to each beat. These notes in solfege with markings will show a similar effect:

- do do do sol la la sol mi mi re re do

Using this method, only the number of notes within a beat can be specified. The actual length of each note is up to tradition and the interpretation of the artist.

Notice that the actual rhythm marks used differ among various traditions.

History and usage

Gongche notation was invented in the Tang Dynasty. It became popular in the Song Dynasty. It is believed to have begun as a tablature of certain musical instrument, possibly using a fixed "do" system. Later it became a popular pitch notation, typically using a movable "do" system.

The notation is not accurate in modern sense. It provides a musical skeleton, allowing an artist to improvise. The details are usually passed on by oral tradition. However, once a tradition is lost, it is very difficult to reconstruct how the music was supposed to sound. Variations among different traditions increased the difficulty in learning the notation.

The system was also introduced to Korea (where it is referred to as gong jeok bo) in ancient times and many traditional musicians still learn their music from such scores (although they typically perform from memory).

Kunkunshi, a Ryukyuan musical notation still in use for sanshin, was directly influenced by Gongche.[1]

External links

| Look up 工尺譜 in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Cantonese Opera (in Chinese) explains how the gongche notation is used in Cantonese opera. This document shows how the same piece of music is written in gongchepu, jianpu, and the standard notation.

References

- East Asia: China, Japan, and Korea (Garland Encyclopedia of World Music). 2001. page 828