Gendered impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

Coronavirus disease 2019 is known to affect both men and women, but the impact of the pandemic and mortality rates are different for men and women.[1] From a purely medical perspective: mortality due to COVID-19 is significantly higher in men in studies conducted in China and Italy.[2][3][4] A higher percentage of nurses are women,[5] which may give them a higher chance of being exposed to the virus.[6]

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

|

|

International response |

|

Medical response |

|

|

|

However, when looking at the larger socio-cultural impacts of the pandemic: School closures, lockdowns and reduced access to healthcare following the COVID-19 pandemic may differentially affect the genders and possibly exaggerate the existing gender disparity.[1][7]

Sex differences in mortality

As of April 2020, men die more often than women after being affected with COVID-19 infection.[1][4][2] The highest risk for men is in their 50s, with the gap between men and women closing only at 90.[4] In China, the death rate was 2.8 percent for men and 1.7 percent for women.[4]

The exact reasons for this sex-difference is not known, but genetic and behavioural factors could be a reason for this difference.[1] Sex-based immunological differences, lesser prevalence of smoking in women and men developing co-morbid conditions such as hypertension at a younger age than women could have contributed to the higher mortality in men.[4] In Europe, 57% of the infected individuals were men and 72% of those died with COVID-19 were men.[8] As of April 2020, the US government is not tracking sex-related data of COVID-19 infections.[9] Research has shown that viral illnesses like Ebola, HIV, influenza and SARS affect men and women differently.[9]

Impact on health

Women as caregivers

Globally, women do three times as much unpaid care work as men.[10][11][12] Evidence from past disease outbreaks show that a greater burden is placed on care in the home and that women are more likely to be caregivers for the sick individuals in the family, making them more vulnerable to infection.[1][13][6] A majority of healthcare workers, particularly nurses, are women. They are on the frontline to combat the disease, which makes women vulnerable to exposure. 90% of the healthcare workers in China's Hubei province (where the disease originated) were women and 78% of the healthcare workers in USA are women.[6]

Women in medical roles

Globally, women make up 70 percent of workers in the health and social sector. Women are playing a disproportionate role in responding to the disease, including as front line healthcare workers (as well as caregivers at home and community leaders and mobilisers). In some countries, COVID-19 infections among female health workers are twice that of their male counterparts.[10][11][12] Women are still paid much less than their male counterparts in almost all countries and hold fewer leadership positions in the health sector. Masks and other protective equipment designed and sized for men leave women at greater risk of exposure.[10][11][12]

Access to healthcare

Women and girls, who already faced health and safety implications in managing their sexual and reproductive health and menstrual hygiene without access to clean water and private toilets before the crisis, are particularly in danger. When healthcare systems are overburdened and resources are reallocated to respond to the pandemic, this can further disrupt health services unique to the well-being of women and girls. This includes pre- and post-natal healthcare, access to quality sexual and reproductive health services, and life-saving care and support for survivors of gender-based violence.[10][14][15][16] Women are also refraining from visiting health facilities due to fears about COVID-19 exposure or due to movement restrictions.[17] The health impacts can be catastrophic, especially in rural, marginalized and low-literacy communities, where women are less likely to have access to quality, culturally-accessible health services, essential medicines or insurance coverage. Before the pandemic, around 810 women died every day from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth — 94 per cent of these deaths occurred in low and lower middle-income countries. Past pandemics have shown increased rates of maternal mortality and morbidity, adolescent pregnancies, and HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. Multiple and intersecting inequalities, such as ethnicity, socioeconomic status, disability, age, race, geographic location and sexual orientation, among others, can further compound these impacts.[10][14][15][16]

Reproductive health

During an outbreak, healthcare resources are diverted to combat the disease, which results in down-prioritizing reproductive health of women.[18][19] The physiological changes in pregnancy puts women at an increased risk for some infections, although evidence is lacking particularly about COVID-19. Women had a higher risk of developing severe illness when affected with influenza virus (which belongs to the same family as COVID-19), so it is important to protect pregnant women from being infected with COVID-19.[20] Women nurses were reported to have decreased access to tampons and sanitary pads while also working overtime without adequate personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic in mainland China.[21] In addition, access to abortion was severely restricted in areas of the United States.

Contraceptives

Supply chain disruptions are limiting availability of contraceptives in many places, and stock-outs of many contraceptive methods are anticipated within the next 6 months in more than a dozen lowest- income countries by UNFPA.[17] Product shortages and lack of access to trained providers or clinics mean that women may be unable to use their preferred method of contraception, may instead use a less effective short-term method, or may discontinue contraceptive use entirely. 47 million women in 114 low and middle-income countries are projected by UNFPA to be unable to use modern contraceptives if the average lockdown, or COVID-19-related disruption, continues for 6 months with major disruptions to services: For every 3 months the lockdown continues, assuming high levels of disruption, up to 2 million additional women may be unable to use modern contraceptives. If the lockdown continues for 6 months and there are major service disruptions due to COVID-19, an additional 7 million unintended pregnancies are expected to occur by UNFPA. The number of unintended pregnancies will increase as the lockdown continues and services disruptions are extended.[22] Reduced access is likely to more adversely affect younger, poorer and more vulnerable and marginalized populations.[17]

Abortion policies

The government of Argentina was planning to submit a bill to the Congress to grant abortion rights to women in March, after the official announcement of president Alberto Fernández in his speech opening the Congress sessions on March, 1.[23] However, the submission of the bill was postponed due to the coronavirus crisis and the lock down of the country.[24] Provision of abortion services under the current law is still being granted in the country,[25] albeit with challenges due to some provinces that have historically opposed abortion. The Ministry of Women of Argentina is working to facilitate abortion through the establishment of a helpline that women can call to obtain information.[26]

Clinical trials

Women are underrepresented in clinical trials for vaccines and drugs, as a result of which sex-differences in disease response could be ignored in scientific studies.[9]

Nutrition

During public health emergencies, women are at an increased risk of malnutrition.[27]

Socio-economic impact

Women constitute a larger part of informal and part-time workers around the world. During periods of uncertainty, such as during a pandemic, women are at a greater risk of being unemployed and being unable to return to work after the pandemic is over.[6] Quarantine experience can be different for men and women, considering the difference in physical, cultural, security and sanitary needs for both genders.[28]

Domestic workers

Domestic work is largely dominated by women and has important levels of informality.[29] In particular, migrant domestic workers are in a more vulnerable situation, with unclear immigration status and lack of legal protection. In situations where those migrant domestic workers come from less-developed countries, their families back home are dependent of their remittance to survive in the country of origin of the worker. In Philippines, those remittances account for 9% of their GDP, therefore impacting their country of origin's economy.[30] In Argentina, they have established a unique-payment for all domestic workers, and childcare and elderly care is deemed an essential activity so they are allowed to circulate even with the lock down.[31]

The U.S. Congress included $3.5 billion in grants for childcare providers in the CARES Act in March 2020. However, this is insufficient to sustain most childcare providers who have lost work. The Center for Law And Policy estimated that childcare providers in the United States will need $9.6 billion per month to economically survive the effects of a hypothetical six-month period of reduced activity.[32]

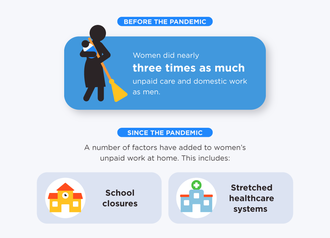

Increase in unpaid care work

Before the crisis started, women did nearly three times as much unpaid care and domestic work as men. Social distancing measures, school closures and overburdened health systems have put an increased demand on women and girls to cater to the basic survival needs of the family and care for the sick and the elderly. With more than 1.5 billion students at home as of March 2020 due to the pandemic, existing gender norms have put the increased demand for unpaid childcare and domestic work on women.[33][34][35][11][36][37][38][10][39] This constrains their ability to carry out paid work, particularly when jobs cannot be carried out remotely. The lack of childcare support is particularly problematic for essential workers and lone mothers who have care responsibilities. Discriminatory social norms are likely to increase the unpaid work load of COVID-19 on girls and adolescent girls, especially those living in poverty or in rural, isolated locations. Evidence from past epidemics shows that adolescent girls are at particular risk of dropping out and not returning to school even after the crisis is over. Women's unpaid care work has long been recognized as a driver of inequality with direct links to wage inequality, lower income, and physical and mental health stressors. As countries rebuild economies, the crisis might offer an opportunity to recognize, reduce and redistribute unpaid care work once and for all.[33][34][35][11][36][37][38][10][39]

Gender based violence

Due to increased tension in the household during a pandemic, women and girls are likely to experience higher risk of intimate partner violence and other forms of domestic violence.[28][40][41] In Kosovo, there has been a 17% increase in gender based violence during the pandemic.[42] During periods of lockdown, women experiencing domestic violence have limited access to protective services.[27][43] In Sint Maarten, the sale of alcohol was temporarily halted to prevent more domestic violence from occurring.[44]

Sources

![]()

References

- Wenham, Clare; Smith, Julia; Morgan, Rosemary (14 March 2020). "COVID-19: the gendered impacts of the outbreak". The Lancet. 395 (10227): 846–848. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30526-2. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7124625. PMID 32151325.

- Chen, Nanshan; Zhou, Min; Dong, Xuan; Qu, Jieming; Gong, Fengyun; Han, Yang; Qiu, Yang; Wang, Jingli; Liu, Ying; Wei, Yuan; Xia, Jia'an; Yu, Ting; Zhang, Xinxin; Zhang, Li (15 February 2020). "Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study". The Lancet. 395 (10223): 507–513. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7135076. PMID 32007143. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- Team, The Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology (17 February 2020). "The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China". Chinese Journal of Epidemiology (in Chamorro). 41 (2): 145–151. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.02.003. ISSN 0254-6450. PMID 32064853. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- Rabin, Roni Caryn (20 March 2020). "In Italy, Coronavirus Takes a Higher Toll on Men". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- "Gender equity in the health workforce: Analysis of 104 countries" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- Gupta, Alisha Haridasani (12 March 2020). "Why Women May Face a Greater Risk of Catching Coronavirus". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- "Gender and the Coronavirus Outbreak: Think Global Health". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- "COVID-19 weekly surveillance report". www.euro.who.int. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- Gupta, Alisha Haridasani (3 April 2020). "Does Covid-19 Hit Women and Men Differently? U.S. Isn't Keeping Track". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- "UN Secretary-General's policy brief: The impact of COVID-19 on women | Digital library: Publications". UN Women. Retrieved 2020-06-12.

- "Gender equality matters in COVID-19 response". UN Women. Retrieved 2020-06-12.

- "COVID-19: Emerging gender data and why it matters | UN Women Data Hub". data.unwomen.org. Retrieved 2020-06-12.

- Davies, Sara E.; Bennett, Belinda (2016). A gendered human rights analysis of Ebola and Zika: locating gender in global health emergencies. pp. 1041–1060. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- "WHO | Progress on drinking water, sanitation and hygiene". WHO. Retrieved 2020-07-01.

- "Home | JMP". washdata.org. Retrieved 2020-07-01.

- "Menstrual Hygiene Management Enables Women and Girls to Reach Their Full Potential". World Bank. Retrieved 2020-07-01.

- "Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Family Planning and Ending Gender-based Violence, Female Genital Mutilation and Child Marriage". www.unfpa.org. Retrieved 2020-06-24.

- Rimmer, MP; Al Wattar, BH; UKARCOG Members (2020-05-27). "Provision of obstetrics and gynaecology services during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a survey of junior doctors in the UK National Health Service". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology: 1471–0528.16313. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.16313. ISSN 1470-0328. PMID 32460422.

- Sochas, Laura; Channon, Andrew Amos; Nam, Sara (2017). Counting indirect crisis-related deaths in the context of a low-resilience health system: the case of maternal and neonatal health during the Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone. pp. iii32–iii39. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 February 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- Stevenson, Alexandra (26 February 2020). "Shaved Heads, Adult Diapers: Life as a Nurse in the Coronavirus Outbreak". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Family Planning and Ending Gender-based Violence, Female Genital Mutilation and Child Marriage (PDF). UNFPA. 2020.

- Página12. "Aborto y otras definiciones centrales de Alberto Fernández en la apertura de sesiones ordinarias 2020 | Lo principal del discurso del Presidente en el Congreso". PAGINA12. Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- Clarín.com. "Por el coronavirus, el Gobierno analiza dilatar el envío al Congreso de dos proyectos clave: aborto legal y reforma judicial". www.clarin.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- Página12. "¿Cómo abortar en época de cuarentena por coronavirus? | Otras urgencias de la salud pública". PAGINA12. Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- Beck, Ingrid. "Abortar en tiempos de coronavirus". Letra P (in Spanish). Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- "Cross-post: An Intersectional Approach to a Pandemic? Gender Data, Disaggregation, and COVID-19". Digital Impact Alliance. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- "COVID-19: A Gender Lens". www.unfpa.org. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- "New strategies to reduce informality in domestic work". www.ilo.org. 2016-12-05. Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- Owen, Lara (2020-03-08). "Five ways the coronavirus is hitting women in Asia". BBC News. Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- "Coronavirus: qué pasa con las niñeras y trabajadoras domésticas en la cuarentena total". El Cronista (in Spanish). Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- Peck, Emily (2020-05-15). "The Child Care Industry Is About To Collapse. There's No Bailout Coming". HuffPost. Retrieved 2020-05-15.

- "Coronavirus puts women in the frontline". European Institute for Gender Equality. Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- "Unpaid care work: Your load and why it matters". interactive.unwomen.org. Retrieved 2020-07-01.

- "Spotlight on SDG 8: The impact of marriage and children on labour market participation | Digital library: Publications". UN Women. Retrieved 2020-07-01.

- https://plus.google.com/+UNESCO (2020-03-31). "Covid-19 school closures around the world will hit girls hardest". UNESCO. Retrieved 2020-07-01.

- https://plus.google.com/+UNESCO (2020-03-04). "Education: From disruption to recovery". UNESCO. Retrieved 2020-07-01.

- UN Women. Families in a changing world / UN Women. New York:. ISBN 1-63214-156-6. OCLC 1120137550.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- Women, U. N. "How COVID-19 impacts women and girls". interactive.unwomen.org. Retrieved 2020-07-01.

- "Gender Equality and Addressing Gender-based Violence (GBV) and Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Prevention, Protection and Response". www.unfpa.org. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- "UN chief calls for domestic violence 'ceasefire' amid 'horrifying global surge'". UN News. 2020-04-05. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- "Gender-based violence spikes amid pandemic, shelters need support". www.unfpa.org. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- "How Coronavirus Is Affecting Victims of Domestic Violence". Time. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- "Alcoholverbod Sint Maarten door stijging huiselijk geweld tijdens lockdown". Telegraaf (in Dutch). 13 April 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2020.