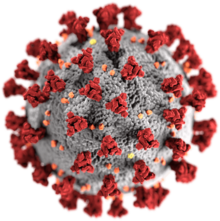

Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the mental health of people around the world.[1] The Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support of the Inter-Agency Standing Committee of the United Nations recommends that the core principles of mental health support during an emergency are "do no harm, promote human rights and equality, use participatory approaches, build on existing resources and capacities, adopt multi-layered interventions and work with integrated support systems."[2] COVID-19 is affecting people's social connectedness, their trust in people and institutions, their jobs and incomes, as well as imposing a huge toll in terms of anxiety and worry.[3] COVID-19 also adds to the complexity of substance use disorders (SUDs) as it disproportionately affects people with SUD due to accumulated social, economic, and health inequities. [4] The health consequences of SUDs ( for example, cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, type 2 diabetes, immunosuppression and central nervous system depression, and psychiatric disorders) and the associated environmental challenges (e.g., housing instability, unemployment, and criminal justice involvement) increase risk for COVID-19. COVID-19 public health mitigation measures (i.e., physical distancing, quarantine and isolation) can exacerbate loneliness, mental health symptoms, withdrawal symptoms and psychological trauma. Confinement rules, unemployment and fiscal austerity measures during and following the pandemic period can affect the illicit drug market and drug use patterns.

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

|

|

International response |

|

Medical response |

|

|

|

Causes of mental health issues during COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused stress, anxiety and worry for many individuals, arising both from the disease itself and from response measures such as social distancing. Common causes of psychological stress during pandemics include, fear of falling ill and dying, avoiding health care due to fear of being infected while in care, fear of losing work and livelihoods, fear of being socially excluded, fear of being placed in quarantine, feeling of powerlessness in protecting oneself and loved ones, fear of being separated from loved ones and caregivers, refusal to care for vulnerable individuals due to fear of infection, feelings of helplessness, lack of self-esteem to do anything in daily life, boredom, loneliness, and depression due to being isolated, and fear of re-living the experience of a previous pandemic.[2]

In addition to these problems, COVID-19 can cause additional psychological responses, such as, risk of being infected when the transmission mode of COVID-19 is not 100% clear, common symptoms of other health problems being mistaken for COVID-19, increased worry about children being at home alone (during school shutdowns, etc.) while parents have to be at work, and risk of deterioration of physical and mental health of vulnerable individuals if care support is not in place.[2]

Frontline workers, such as doctors and nurses may experience additional mental health problems. Stigmatization towards working with COVID-19 patients, stress from using strict biosecurity measures (such as physical strain of protective equipment, need for constant awareness and vigilance, strict procedures to follow, preventing autonomy, physical isolation making it difficult to provide comfort to the sick), higher demands in the work setting, reduced capacity to use social support due to physical distancing and social stigma, insufficient capacity to give self-care, insufficient knowledge about the long-term exposure to individuals infected with COVID-19, and fear that they could pass infection to their loved ones can put frontline workers in additional stress.[2][5][6]

Fear, anger and hopelessness were the most frequent traumatic emotional responses in the general public during the first COVID-19 outbreak in the Czech Republic. The four most frequent categories of fear were determined: fear of the negative impact on household finances, fear of the negative impact on the household finances of significant others, fear of the unavailability of health care, and fear of an insufficient food supply.[7]

Prevention and management of mental health conditions

_v1.jpg)

World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control guidelines

The World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control have issued guidelines for preventing mental health issues during the COVID-19 pandemic. The summarized guidelines are as follows:[8][9]

For general population

- Be empathetic to all the affected individuals, regardless of their nationality or ethnicity.

- Use people-first language while describing individuals affected with COVID-19.

- Minimize watching the news if that makes one anxious. Seek information only from trusted sources, preferably once or twice a day.

- Protect yourself and be supportive to others, such as your neighbours.

- Find opportunities to amplify positive stories of local people who have experienced COVID-19.

- Honor healthcare workers who are supporting those affected with COVID-19.

For healthcare workers

- Feeling under pressure is normal during the times of a crisis. Managing one's mental health is as important as managing physical health.

- Follow coping strategies, ensure sufficient rest, eat good food, engage in physical activity, avoid using tobacco, alcohol, or drugs. Use the coping strategies that have previously worked for you under stressful situations.

- If one is experiencing avoidance by the family or the community, stay connected with loved ones, including digital methods.

- Use understandable ways to share messages to people with disabilities.

- Know how to link people affected with COVID-19 with available resources.

For team leaders in health facilities

- Keep all staff protected from poor mental health. Focus on long-term occupational capacity rather than short term results.

- Ensure good quality communication and accurate updates.

- Ensure that all staff are aware of where and how mental health support can accessed.

- Orient all staff on how to provide psychological first aid to the affected.

- Emergency mental health conditions should be managed in healthcare facilities.

- Ensure availability of essential psychiatric medications at all levels of health care.

For carers of children

- Help children find positive ways to express their emotions.

- Avoid separating children from their parents/carers as much as possible. Ensure that regular contact with parents and carers is maintained, should the child be placed in isolation.

- Maintain family routines as much as possible and provide age-appropriate engaging activities for children.

- Children might seek more attachment from parents, in which case, discuss about COVID-19 with them in an age-appropriate way.

For older adults, people with underlying health conditions, and their carers

- Older adults, those especially in isolation or suffering from pre-existing neurological conditions, may become more anxious, angry, or withdrawn. Provide practical and emotional support through caregivers and healthcare professionals.

- Share simple facts on the crisis and give clear information about how to reduce the risk of infection.

- Have access to all the medications that are currently being used.

- Know in advance where and how to get practical help.

- Learn and perform simple daily exercises to practice at home.

- Keep regular schedules as much as possible and keep in touch with loved ones.

- Indulge in a hobby or task that helps focus the mind on other aspects.

- Reach out to people digitally or telephonically to have normal conversations or do a fun activity together online.

- Try and do good for the community with social distancing measures in place. It could be providing meals to the needy, dry rations, or coordination.

For people in isolation

- Stay connected and maintain social networks.

- Pay attention to your own needs and feelings. Engage in activities that you find relaxing.

- Avoid listening to rumors that make you uncomfortable.

Countries

China

A detailed psychological intervention plan was developed by the Second Xiangya Hospital, the Institute of Mental Health, the Medical Psychology Research Center of the Second Xiangya Hospital, and the Chinese Medical and Psychological Disease Clinical Medicine Research Center. It focused on building a psychological intervention medical team to provide online courses for medical staff, a psychological assistance hotline team, and psychological interventions.[10] Online mental health education and counselling services were created for social media platforms such as WeChat, Weibo, and TikTok that were widely used by medical staff and the public. Printed books about mental health and COVID-19 were republished online with free electronic copies available through the Chinese Association for Mental Health.[11]

United States

Due to the increase in telecommunication for medical and mental health appointments, the United States government loosened the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) through a limited waiver. This allows clinicians to evaluate and treat individuals though video chatting services that were not previously compliant, allowing for patients to socially distance and receive care.[12]

Impact on individuals with anxiety disorders

Obsessive–compulsive disorder

There has been a heightened concern for individuals suffering from obsessive–compulsive disorder, especially in regards to long-term consequences.[13][14] Fears regarding infection by the virus, and public health tips calling for hand-washing and sterilization are triggering related compulsions in some OCD sufferers.[15] Some OCD sufferers with cleanliness obsessions are noticing their greatest fears realized.[16][17] Amid guidelines of social-distancing, quarantine, and feelings of separation, some sufferers are seeing an increase in intrusive thoughts, unrelated to contamination obsessions.[18][19]

Post-traumatic stress disorder

There has been a particular concern for sufferers of post-traumatic stress disorder, as well as the potential for medical workers and COVID–19 patients to develop PTSD-like symptoms.[20][21][22] In late March 2020, researchers in China found that, based on a PTSD checklist questionnaire provided to 714 discharged COVID–19 patients, 96.2% had serious prevalent PTSD symptoms.[23]

Impact on children

Academics have reported that many children who were separated from caregivers during the pandemic may place them into a state of crisis, and those who were isolated or quarantined during past pandemic disease are more likely to develop acute stress disorders, adjustment disorders and grief, with 30% of children meeting the clinical criteria for PTSD.[24]

School closures also caused anxiety for students with special needs as daily routines are suspended or changed and all therapy or social skills groups also halted. Others who have incorporated their school routines into coping mechanisms for their mental health, have had an increase in depression and difficulty in adjusting back into normal routines. Additional concern has been shown towards children being placed in social isolation due to the pandemic, as rates of child abuse, neglect, and exploitation increased after the Ebola outbreak.[25] The closures have also limited the amount of mental health services that some children have access to, and some children are only identified as having a condition due to the training and contact by school authorities and educators.[12] A recent article published from India has observed a very high value of psychological distress in children due to covid-19 pandemic.In this study, most (around 68%) of quarantined children showed some or other form of psychological distress which is much higher than the non-quarantined group especially worry, fear and helplessness (ref-Saurabh, K., Ranjan, S. Compliance and Psychological Impact of Quarantine in Children and Adolescents due to Covid-19 Pandemic. Indian J Pediatr 87, 532–536 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-020-03347-3)

Impact on essential workers and medical personnel

Many medical staff in China refused psychological interventions even though they showed sign of distress by; excitability, irritability, unwillingness to rest and others, stating they did not need a psychologist but more rest without interruption and enough protective supplies. They also stated using the psychologists skills instead towards the patients anxiety, panic, and other emotional problems instead of having the medical staff treat these issues.[10]

Impact on suicides

The coronavirus pandemic has been followed by a concern for a potential spike in suicides, exacerbated by social isolation due to quarantine and social-distancing guidelines, fear, and unemployment and financial factors.[26][27]

Germany

The state finance minister of Hesse, Germany, committed suicide possibly due to the mental stress from having to deal with the financial consequences of COVID-19.[28]

India

There are reports of people committing suicide after not being able to access alcohol during the lockdown associated with coronavirus pandemic in India.[29]

Ireland

A newly-established hotline for older people alone saw 16,000 calls since its March 2020 launch.[30]

Japan

Several counseling helplines by telephone or text message are provided by many organizations, including the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.[31]

On February 1, 2020, a man who belonged to Cabinet Secretariat and engaged in receiving returners from Wuhan committed suicide and died.[32] He was tortured by the returners for their discontent.[33] On April 30, a tonkatsu chef committed self-immolation at his restaurant.[34] He had been designated as torch relay runner for the 2020 Summer Olympics, but it was postponed and the restaurant was forced to close.[34][35]

Poland

On March 18, 2020, Polish gynecologist Wojciech Rokita committed suicide due to the backlash and hate he received after being the first person to be diagnosed with COVID-19 in the Polish city Kielce.[36]

United States

In March 2020, the federal crisis hotline, Disaster Distress Helpline, received a 338% increase in calls compared to the previous month (February 2020) and an 891% increase in calls compared to the previous year (March 2019).[37] In May 2020, the public health group Well Being Trust estimated that, over the coming decade of the 2020s, the pandemic and the related recession might indirectly cause an additional 75,000 "deaths of despair" (including overdose and suicide) than would otherwise be expected in the United States.[38][39]

Mental health aftercare

Academics have theorized that once the pandemic stabilizes or fully ends, supervisors should ensure that time is made to reflect on and learn from the experiences by first responders, essential workers, and the general population to create a meaningful narrative rather than focusing on the trauma. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence has recommended the active monitoring of staff for issues such as PTSD, moral injuries, and other associated mental illness.[40]

Long-term consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health

According to the Inter-Agency Standing Committee Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (IASC), there can be long-term consequences due to the coronavirus pandemic. Deterioration of social networks and economies, stigma towards survivors of COVID-19, possible higher anger and aggression of frontline workers and the government, possible anger and aggression against children, and possible mistrust of information provided by official authorities are some of the long-term consequences anticipated by the IASC.[2] In South Africa, where one in four young men between the ages of 14 years and 24 years reported current suicidal thoughts[41] even before the COVID-19 pandemic, one wonders what the future holds for their well-being.

Some of these consequences could be due to realistic dangers, but many reactions could be borne out of lack of knowledge, rumors, and misinformation.[42] It is also possible that some people may have positive experiences, such as pride about finding ways of coping. It is likely that community members show altruism and cooperation when faced with a crisis, and people might experience satisfaction from helping others.[43]

References

- CDC (11 February 2020). "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "Inter-Agency Standing Committee Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial support" (PDF). MH Innovation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- "OECD". read.oecd-ilibrary.org. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Jemberie, W. B.; Stewart Williams, J.; Eriksson, M.; Grönlund, A-S.; Ng, N.; Blom Nilsson, M.; Padyab, M.; Priest, K. C.; Sandlund, M.; Snellman, F.; McCarty, D.; Lundgren, L. M.; et al. (21 July 2020). "Substance Use Disorders and COVID-19: Multi-Faceted Problems Which Require Multi-Pronged Solutions". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 11. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00714.

- "ICN COVID-19 Update: New guidance on mental health and psychosocial support will help to alleviate effects of stress on hard-pressed staff". ICN - International Council of Nurses. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- "Emergency Responders: Tips for taking care of yourself". emergency.cdc.gov. 10 January 2020. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Trnka, Radek; Lorencova, Radmila (June 2020). "Fear, anger, and media-induced trauma during the outbreak of COVID-19 in the Czech Republic". Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 12 (5): 546–549. doi:10.1037/tra0000675. PMID 32538654. S2CID 219702140.

- "Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak" (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Chen, Qiongni; Liang, Mining; Li, Yamin; Guo, Jincai; Fei, Dongxue; Wang, Ling; He, Li; Sheng, Caihua; Cai, Yiwen; Li, Xiaojuan; Wang, Jianjian (1 April 2020). "Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak". The Lancet Psychiatry. 7 (4): e15–e16. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X. ISSN 2215-0366. PMC 7129426. PMID 32085839.

- Liu, Shuai; Yang, Lulu; Zhang, Chenxi; Xiang, Yu-Tao; Liu, Zhongchun; Hu, Shaohua; Zhang, Bin (1 April 2020). "Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak". The Lancet Psychiatry. 7 (4): e17–e18. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30077-8. ISSN 2215-0366. PMC 7129099. PMID 32085841.

- Golberstein, Ezra; Wen, Hefei; Miller, Benjamin F. (14 April 2020). "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Mental Health for Children and Adolescents". JAMA Pediatrics. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456. PMID 32286618.

- Katherine Rosman (3 April 2020). "For Those With O.C.D., a Threat That Is Both Heightened and Familiar". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Fineberg, N. A.; Van Ameringen, M.; Drummond, L.; Hollander, E.; Stein, D. J.; Geller, D.; Walitza, S.; Pallanti, S.; Pellegrini, L.; Zohar, J.; Rodriguez, C. I.; Menchon, J. M.; Morgado, P.; Mpavaenda, D.; Fontenelle, L. F.; Feusner, J. D.; Grassi, G.; Lochner, C.; Veltman, D. J.; Sireau, N.; Carmi, L.; Adam, D.; Nicolini, H.; Dell'Osso, B.; et al. (12 April 2020). "How to manage obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) under COVID-19: A clinician's guide from the International College of Obsessive Compulsive Spectrum Disorders (ICOCS) and the Obsessive-Compulsive Research Network (OCRN) of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology". Comprehensive Psychiatry. 100: 152174. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152174. PMC 7152877. PMID 32388123.

- Pyrek, Emily (15 April 2020). "COVID-19 proving extra challenging for people with OCD and other mental health conditions". La Crosse Tribune. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Moore, Georgie (22 April 2020). "Battling anxiety in the age of COVID-19". Australian Associated Press. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Sparrow, Wendy (24 March 2020). "'COVID-19 Is Giving Everyone A Small Glimpse Of What It's Like To Live With OCD'". Women's Health. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Welch, Craig (15 April 2020). "Are we coping with social distancing? Psychologists are watching warily". National Geographic. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Zakarin, Jordan (2 April 2020). "A Pandemic Is Hell For Everyone, But Especially For Those With OCD". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Turay Jr., Ismail (28 March 2020). "COVID-19: Social distancing may affect one's mental health, experts say". Dayton Daily News. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Jain MD, Shaili (13 April 2020). "Bracing for an Epidemic of PTSD Among COVID-19 Workers". Psychology Today. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "UPMC psychologist discusses mental health impact of COVID-19 on patients with PTSD, trauma". WJAC 6. 25 April 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Aten Ph.D., Jamie D. (4 April 2020). "Are COVID-19 Patients at Risk for PTSD?". Psychology Today. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Liu, Jia Jia; Bao, Yanping; Huang, Xiaolin; Shi, Jie; Lu, Lin (1 May 2020). "Mental health considerations for children quarantined because of COVID-19". The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. 4 (5): 347–349. doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30096-1. ISSN 2352-4642. PMC 7118598. PMID 32224303.

- Lee, Joyce (14 April 2020). "Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19". The Lancet. Child & Adolescent Health. 4 (6): 421. doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30109-7. ISSN 2352-4642. PMC 7156240. PMID 32302537.

- Gunnell, David; et al. (21 April 2020). "Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic". The Lancet. 7 (6): 468–471. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30171-1. PMC 7173821. PMID 32330430. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Baker, Noel (22 April 2020). "Warning Covid-19 could lead to spike in suicide rates". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "German state finance minister Thomas Schäfer found dead". DW.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- "Two tipplers in Kerala commit suicide upset at not getting liquor during COVID-19 lockdown". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- Hilliard, Mark (27 April 2020). "'Cocooning' and mental health: Over 16,000 calls to Alone support line". The Irish Times. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "新型コロナウイルス感染症対策(こころのケア)|こころの耳:働く人のメンタルヘルス・ポータルサイト". kokoro.mhlw.go.jp. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- "神戸新聞NEXT|全国海外|社会|内閣官房職員、飛び降り自殺か" (in Japanese). Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- INC, SANKEI DIGITAL (7 February 2020). "新型コロナ、自殺した職員らに帰国者から寄せられた苛烈怒号:イザ!". イザ! (in Japanese). Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- "聖火当選の歓喜、コロナで一転 絶望の店主、火災で死亡:朝日新聞デジタル". 朝日新聞デジタル (in Japanese). Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- "聖火ランナーのとんかつ店主、火災で死亡 生前は延期や新型コロナ影響を悲観". 毎日新聞 (in Japanese). Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- "Lekarz z Kielc nie żyje. Był zaszczuty przez ludzką nienawiść". Fakt.pl. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- Jackson, Amanda (10 April 2020). "A crisis mental-health hotline has seen an 891% spike in calls". CNN. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Simon, Mallory (8 May 2020). "75,000 Americans at risk of dying from overdose or suicide due to coronavirus despair, group warns". CNN. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- Well Being Trust & The Robert Graham Center Analysis. "The COVID Pandemic Could Lead to 75,000 Additional Deaths from Alcohol and Drug Misuse and Suicide". Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- Greenberg, Neil; Docherty, Mary; Gnanapragasam, Sam; Wessely, Simon (26 March 2020). "Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic". BMJ. 368: m1211. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1211. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 32217624.

- Mngoma, Nomusa F.; Ayonrinde, Oyedeji A.; Fergus, Stevenson; Jeeves, Alan H.; Jolly, Rosemary J. (20 April 2020). "Distress, desperation and despair: anxiety, depression and, suicidality among rural South African youth". International Review of Psychiatry. 0 (0): 1–11. doi:10.1080/09540261.2020.1741846. ISSN 0954-0261. PMID 32310008.

- Tyler, Wat (8 May 2020). "The Bottomless Pit: Social Distancing, COVID-19 & The Bubonic Plague". Sandbox Watch. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "Social Distancing: How To Keep Connected And Upbeat". SuperWellnessBlog. 29 April 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2020.