COVID-19 testing

COVID-19 testing involves analyzing samples to assess the current or past presence of SARS-CoV-2. The two main branches detect either the presence of the virus or of antibodies produced in response to infection.[1][2] Tests for viral presence are used to diagnose individual cases and to allow public health authorities to trace and contain outbreaks. Antibody tests instead show whether someone once had the disease. They are less useful for diagnosing current infections because antibodies may not develop for weeks after infection.[3] It is used to assess disease prevalence, which aids the estimation of the infection fatality rate.[4]

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

|

|

International response |

|

Medical response |

|

|

|

Individual jurisdictions have adopted varied testing protocols, including whom to test, how often to test, analysis protocols, sample collection and the uses of test results.[5][6][7] This variation has likely significantly impacted reported statistics, including case and test numbers, case fatality rates and case demographics.[8][9][10]

Test analysis is often performed in automated, high-throughput, medical laboratories by medical laboratory scientists. Alternatively, point-of-care testing can be done in physician's offices, workplaces, institutional settings or transit hubs.

Methods

Positive viral tests indicate a current infection, while positive antibody tests indicate a prior infection.[12] Other techniques include a CT scan, checking for elevated body temperature or checking for low blood oxygen level.

Detection of the virus

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a process that amplifies (replicates) a small, well-defined segment of DNA many hundreds of thousands of times, creating enough of it for analysis. Test samples are treated with certain chemicals[13][14] that allow DNA to be extracted. Reverse transcription converts RNA into DNA.

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) first uses reverse transcription to obtain DNA, followed by PCR to amplify that DNA, creating enough to be analyzed.[14] RT-PCR can thereby detect SARS-CoV-2, which contains only RNA. The RT-PCR process generally requires a few hours.[15]

Real-time PCR (qPCR)[16] provides advantages including automation, higher-throughput and more reliable instrumentation. It has become the preferred method.[17][18]

The combined technique has been described as real-time RT-PCR[19] or quantitative RT-PCR[20] and is sometimes abbreviated qRT-PCR[21] rRT-PCR[22] or RT-qPCR,[23] although sometimes RT-PCR or PCR are used. The Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines propose the term RT-qPCR,[24] but not all authors adhere to this.

Samples can obtained by various methods, including a nasopharyngeal swab, sputum (coughed up material),[25] throat swabs,[26] deep airway material collected via suction catheter[26] or saliva.[27][28] Drosten et al. remarked that for 2003 SARS, "from a diagnostic point of view, it is important to note that nasal and throat swabs seem less suitable for diagnosis, since these materials contain considerably less viral RNA than sputum, and the virus may escape detection if only these materials are tested."[29]

The likelihood of detecting the virus depends on collection method and how much time has passed since infection. According to Drosten tests performed with throat swabs are reliable only in the first week. Thereafter the virus may abandon the throat and multiply in the lungs. In the second week, sputum or deep airways collection is preferred.[26]

Collecting saliva may be as effective as nasal and throat swabs,[27] although this is not certain.[30][28] Sampling saliva may reduce the risk for health care professionals by eliminating close physical interaction.[31] It is also more comfortable for the patient.[32] Quarantined people can collect their own samples.[31] A saliva test's diagnostic value depends on sample site (deep throat, oral cavity, or salivary glands).[28] One study found that saliva yielded greater sensitivity and consistency when compared with swab samples.[33] On 15 August 2020, the US FDA authorized a saliva test developed at Yale University, which gives results in hours.[34]

Viral burden measured in upper respiratory specimens declines after symptom onset.[35]

.jpg) Demonstration of a nasopharyngeal swab for COVID-19 testing

Demonstration of a nasopharyngeal swab for COVID-19 testing.jpg) Demonstration of a throat swab for COVID-19 testing

Demonstration of a throat swab for COVID-19 testing- A PCR machine

Isothermal amplification assays

Isothermal nucleic acid amplification tests also amplify the virus's genome. They are faster than PCR because they don't involve repeated heating and cooling cycles. These tests typically detect DNA using fluorescent tags, which are read out with specialized machines. CRISPR gene editing technology was modified to perform the detection: if the CRISPR enzyme attaches to the sequence, it colors a paper strip. The researchers expect the resulting test to be cheap and easy to use in point-of-care settings.[36][37] The test amplifies RNA directly, without the RNA-to-DNA conversion step of RT-PCR.[38]

Antigen

An antigen is the part of a pathogen that elicits an immune response. Antigen tests look for antigen proteins from the viral surface. In the case of a coronavirus, these are usually proteins from the surface spikes.[39] One of the challenges is to find a target unique to SARS-CoV-2.[40]

Antigen tests may be one way to scale up testing to much greater levels.[39] Isothermal nucleic acid amplification tests can process only one sample at a time per machine. RT-PCR tests are accurate but require too much time, energy and trained personnel to run the tests.[39] "There will never be the ability on a [PCR] test to do 300 million tests a day or to test everybody before they go to work or to school," Deborah Birx, head of the White House Coronavirus Task Force, said on 17 April 2020. "But there might be with the antigen test."[41]

A nasopharyngeal swab is exposed to paper strips containing artificial antibodies designed to bind to coronavirus antigens. Antigens bind to the strips and give a visual readout. The process takes less than 30 minutes, can deliver results at point of care, and does not require expensive equipment or extensive training.[39]

Swabs of respiratory viruses often lack enough antigen material to be detectable.[40] This is especially true for asymptomatic patients who have little if any nasal discharge. Viral proteins are not amplified in an antigen test.[39][42] According to the WHO the sensitivity of similar antigen tests for respiratory diseases like the flu ranges between 34% and 80%. "Based on this information, half or more of COVID-19 infected patients might be missed by such tests, depending on the group of patients tested," the WHO said. Many scientists doubt whether an antigen test can be made reliable enough in time to be useful against COVID-19.[42] According to the FDA, positive results from antigen tests are highly accurate, but there is a higher chance of false negatives, so negative results do not rule out infection. Therefore, negative results from an antigen test may need to be confirmed with a PCR test.[43]

Imaging

Typical visible features on CT initially include bilateral multilobar ground-glass opacities with a peripheral or posterior distribution.[44] Subpleural dominance, crazy paving, and consolidation may develop as the disease evolves.[44][45] Chest CT scans and chest x-rays are not recommended for diagnosing COVID-19. Radiologic findings in COVID-19 lack specificity.[46][44]

Antibody tests

Blood tests (serology tests) may be able to identify once-infected people who have recovered,[47] however the timing of when people are tested is important.[48] SARS-CoV-2 antibodies' potency and protective period are unknown.[4][49] The potential role of antibody testing for determining if a person is immune to COVID-19 is not clear and the ability to detect SARS-COV-2 antibodies in people recovering from an infection, people who are asymptomatic, and those who had mild symptoms needs further research.[48]

Part of the immune system's response to infection is the production of antibodies, including IgM and IgG. According to the FDA, IgM antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 are generally detectable several days after initial infection, although levels over the course of infection and beyond are not well characterized.[50] SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies generally become detectable 10–14 days after infection, sometimes earlier, and normally peak around 28 days after infection onset.[51][52] Antibodies emerge too late to serve as acute infection markers and only 30% of people who are COVID-19 positive were found to have detectable antibodies on day 7 of their infection.[48] Antibodies for some diseases persist in the bloodstream for many years, while others quickly fade away.[39]

Types

Rapid diagnostic test (RDT)

RDTs typically use a small, portable, positive/negative lateral flow assay that can be executed at point of care. RDTs may process blood samples, saliva samples, or nasal swab fluids. RDTs produce colored lines to indicate positive or negative results.[53]

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

ELISAs can be qualitative or quantitative and generally require a lab. These tests usually use whole blood, plasma, or serum samples. A plate is coated with a viral protein, such as a SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Samples are incubated with the protein, allowing any antibodies to bind to it. The antibody-protein complex can then be detected with another wash of antibodies that produce a color/fluorescent readout.[53]

Neutralization assay

Neutralization assays assess whether sample antibodies prevent viral infection in test cells. These tests sample blood, plasma or serum. The test cultures cells that allow viral reproduction (e.g., VeroE6 cells). By varying antibody concentrations, researchers can visualize and quantify how many test antibodies block virus replication.[53]

Chemiluminescent immunoassay

Chemiluminescent immunoassays are quantitative lab tests. They sample blood, plasma, or serum. Samples are mixed with a known viral protein, buffer reagents and specific, enzyme-labeled antibodies. The result is luminescent. A chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay uses magnetic, protein-coated microparticles. Antibodies react to the viral protein, forming a complex. Secondary enzyme-labeled antibodies are added and bind to these complexes. The resulting chemical reaction produces light. The radiance is used to calculate the number of antibodies. This test can identify multiple types of antibodies, including IgG, IgM, and IgA.[53]

Neutralizing vs binding antibodies

Most if not all large scale COVID-19 antibody testing looks for binding antibodies only and does not measure the more important neutralizing antibodies (NAb).[54][55][56] A NAb is an antibody that defends a cell from an infectious particle by neutralizing its biological effects. Neutralization renders the particle no longer infectious or pathogenic.[57] A binding antibody binds to the pathogen but the pathogen remains infective; the purpose can be to flag the pathogen for destruction by the immune system.[58] It may even enhance infectivity by interacting with receptors on macrophages.[59] Since most COVID-19 antibody tests return a positive result if they find only binding antibodies, these tests cannot indicate that the subject has generated protective NAbs that protect against re-infection.[55][56]

It is expected that binding antibodies imply the presence of NAbs[56] and for many viral diseases total antibody responses correlate somewhat with NAb responses[60] but this is not established for COVID-19. A study of 175 recovered patients in China who experienced mild symptoms reported that 10 individuals had no detectable NAbs at discharge, or thereafter. How these patients recovered without the help of NAbs and whether they were at risk of re-infection was not addressed.[55] An additional source of uncertainty is that even if NAbs are present, viruses such as HIV can evade NAb responses.[54]

Studies have indicated that NAbs to the original SARS virus (the predecessor to the current SARS-CoV-2) can remain active for two years[61] and are gone after six years.[62] Nevertheless, memory cells including Memory B cells and Memory T cells[63] can last much longer and may have the ability to reduce reinfection severity.[62]

.jpg) A Point of Care Test in Peru. A blood droplet is collected by a pipette.

A Point of Care Test in Peru. A blood droplet is collected by a pipette..jpg) Blood from pipette is then placed onto a COVID-19 rapid diagnostic test device.

Blood from pipette is then placed onto a COVID-19 rapid diagnostic test device.

Other tests

Following recovery, many patients no longer have detectable viral RNA in upper respiratory specimens. Among those who do, RNA concentrations three days following recovery are generally below the range in which replication-competent virus has been reliably isolated.[64]

No clear correlation has been described between length of illness and duration of post-recovery shedding of viral RNA in upper respiratory specimens.[65]

Infectivity

Infectivity is indicated by the basic reproduction number (R0, pronounced "R naught") of the disease.[66] SARS-CoV-2 is estimated to have an R0 of 2.2 to 2.5.[67][68] This means that in a population where all individuals are susceptible to infection, each infected person is expected to infect 2.2 to 2.5 others in the absence of interventions.[69] R0 can vary according factors such as geography, population demographics and density.[70] In New York state R0 was estimated to be 3.4 to 3.8.[71]

On average, an infected person begins showing symptoms five days after infection (the "incubation period") and can infect others beginning two to three days before that.[67][72] One study reported that 44% of viral transmissions occur within this period.[67][73] According to CDC, a significant number of infected people who never show symptoms are nevertheless contagious.[73][68] In vitro studies have not found replication-competent virus after 9 days from infection.[74] The statistically estimated likelihood of recovering replication-competent virus approaches zero by 10 days.[75]

Infectious virus has not been cultured from urine or reliably cultured from feces;[76] these potential sources pose minimal if any risk of transmitting infection and any risk can be sufficiently mitigated by good hand hygiene.

Patterns and duration of illness and infectivity have not been fully described. However, available data indicate that SARS-CoV-2 RNA shedding in upper respiratory specimens declines after symptom onset. At 10 days recovery of replication-competent virus in viral culture (as a proxy of the presence of infectious virus) approaches zero. Although patients may produce PCR-positive specimens for up to six weeks,[77] it remains unknown whether these samples hold infectious virus. After clinical recovery, many patients do not continue to shed. Among recovered patients with detectable RNA in upper respiratory specimens, concentrations after three days are generally below levels where virus has been reliably cultured. These data were generated from adults across a variety of age groups and with varying severity of illness. Data from children and infants were not available.[74]

History

January

Scientists from China first released information on the viral genome on 11 January 2020,[79][80] sending multiple genomic sequences to GISAID, an indispensable mechanism for sharing influenza genetic sequence data.[81] That day the Malaysian Institute for Medical Research (IMR) produced "primers and probes" specific to a SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR test.[82] The IMR's materials were used to diagnose Malaysia's first patient on 24 January.[83] BGI Group was one of the first companies to receive emergency use approval from China's National Medical Products Administration for a nucleic acid test.[84]

Public Health England announced a test on the 10th,[85] using a real-time RT-PCR (RdRp gene) assay based on oral swabs.[86] The test detected the presence of any type of coronavirus, including specifically identifying SARS-CoV-2. It was rolled out to twelve laboratories across the United Kingdom on 10 February.[87]

The first case in South Korea was confirmed on 19 January.[88]

The German nucleic acid testing protocol was published on the 17th. Another early PCR test was developed by Charité University hospital in Berlin, working with academic collaborators in Europe and Hong Kong, and published on the 23rd. It used rtRT-PCR, and formed the basis of 250,000 kits distributed by the World Health Organization (WHO).[89]

In the US, the CDC developed its SARS-CoV-2 Real Time PCR Diagnostic Panel.[90] The protocol became available on the 28th.[91] One of three tests in early kits failed due to faulty reagents.

In Russia, the first COVID‑19 test was developed by the State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology VECTOR. Production began on 24 January.[92]

February

CDC refused to let other labs process tests that month; allowing an average of fewer than 100 samples/day to be processed. Tests using two components were not determined to be reliable until the 28th, and only then were state and local laboratories permitted to begin testing.[93] The test was approved by the FDA under an EUA.South Korean company Kogenebiotech's clinical grade, nucleic acid test (PowerChek Coronavirus) was approved by Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) on 4 February.[94]

In Wuhan BGI opened a makeshift 2000-sq-meter emergency detection laboratory named "Huo-Yan" (Chinese: 火眼, "Fire Eye") on the 5th.[95][96] It processed more than 10,000 samples/day.[97][96] Construction required 5 days.[98] The Wuhan Laboratory was followed by Huo-Yan labs in Shenzhen, Tianjin, Beijing, and Shanghai, in a total of 12 cities across China.

On 11 February the test was approved by the Federal Service for Surveillance in Healthcare.[99]

March

By 4 March China reached 50,000 tests per day.[100]

On the 16th WHO called for ramping up testing programmes as the best way to slow the spread.[101][102]

Shortages of reagent and other supplies became a bottleneck for mass testing in the EU and UK[103] and the US.[104][105]

On 12 March, Mayo Clinic announced a nucleic acid test.[106]

Early in March, China reported accuracy problems with its PCR tests.[107] A study examined 1070 samples from 205 Wuhan patients and reported varied sensitivity according to the methods and location of sample collection. Samples from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid specimens returned the highest sensitivity.[108] The authors argued that CT scans showed even higher sensitivity.[109]

US commercial labs began testing in early March. As of the 5th LabCorp announced nationwide availability of COVID‑19 testing based on RT-PCR.[110] Quest Diagnostics made nationwide testing available as of 9 March.[111] US testing demand grew rapidly, causing backlogs of hundreds of thousands of tests at private US labs. Supplies of swabs and chemical reagents continued strained.[112] On 25 May, the US required each state to take responsibility for meeting its testing needs.[113] In March, the FDA issued EUAs for nucleic acid tests to Hologic (3/16),[114] Abbott Laboratories (3/18),[115] Thermo Fisher Scientific (3/19)[116] Cepheid (3/21)[117][118] and LabCorp (4/30).[115]

On 27 March the FDA issued an EUA for a test using Abbott Laboratories' ID Now assay.[119]

By 31 March United Arab Emirates was testing more of its population per head than any other country.[120] UAE implemented a combination of drive-through sample collection, and a mass-throughput laboratory from Group 42 and BGI. The lab conduced tens of thousands RT-PCR tests per day and was the first to be operational at that scale other than China.[121]

Several European countries initially conducted more tests than the US.[122][123] By 19 March drive-in tests were offered in several large cities.[124] As of 26 March, German Health Minister Jens Spahn estimated that Germany was conducting 200,000 tests per week.[125] As of the end of March at least 483,295 samples were tested and 33,491 (6.9%) had tested positive.[126]

80% of test kits that Czechia purchased from China gave wrong results.[127][128] Slovakia purchased 1.2 million antibody-based test kits from China that were found to be inaccurate.[129] China accused Czechia and Slovakia of incorrect use of those tests.[130] Ateş Kara of the Turkish Health Ministry said the test kits Turkey purchased from China had a "high error rate".[131][132]

Germany has a large medical diagnostics industry, with more than a hundred testing labs that provided the technology and infrastructure to enable rapid increases in testing. Costs are borne by insurance when the test is ordered by a physician.[133] According to the president of the Robert Koch Institute, as of 22 March, Germany had capacity for 160,000 tests per week.[134]

Spain purchased test kits from Chinese firm Shenzhen Bioeasy Biotechnology Co Ltd, but found that results were unacceptable. The maker explained that the incorrect results may stem from failure to collect samples or use the kits correctly. The Spanish ministry switched to another vendor, Shenzhen Bioeasy.[135]

By month end, testing had surpassed 200k/week.[136]

April

The FDA gave an EUA for the US' first antibody test on the 2nd.[137][49]

As of 7 April, WHO had accepted two diagnostic tests for procurement under the Emergency Use Listing procedure (EUL).[138]

On 13 April, Health Canada approved a nucleic acid test from Spartan Bioscience. Institutions may "test patients" with a handheld DNA analyzer "and receive results without having to send samples away to a [central] lab".[139][140]

By the start of April, the United Kingdom was delivering around 10,000 swab tests per day.[141] The British NHS announced that it was piloting a scheme to test suspected cases at home, to remove the risk of one patient infecting others at a hospital or disinfecting an ambulance used to transport a patient.[142]

The UK purchased 3.5 million antibody test kits from China, but in early April 2020 announced these were not usable.[143][144] On 21 April 2020, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) advised Indian states to stop using test kits purchased from China after receiving complaints from one state. Rajasthan health minister Raghu Sharma on 21 April said the kits gave only 5.4 percent accurate results.[145]

Antibody survey results found from 2% to 30% positive.[146] On preliminary data, WHO concluded that 2% to 3% of the world population had developed antibodies.[147]

By month end, testing had surpassed 750k/week.[136]

May

In May antibody tests were conducted on 5,603 major league baseball employees and 0.7% tested positive, showing that they had been infected. 70% of those who tested positive had had no symptoms.[148][149][150] The US was conducting an average of 2.5 million tests per week for the week ending 17 May. This grew to 3.2 million by 14 June.[151][152]

Attempts to culture virus from upper respiratory specimens were largely unsuccessful when viral burden is low but detectable (i.e., Ct values higher than 33-35).[74]

On 3 May, Roche received an EUA for a selective ELISA serology test.[153][154]

On 8 May, the FDA granted its first EUA for antigen test: "Sofia 2 SARS Antigen FIA" by Quidel Corp.[155][43]

The FDA announced on 14 May a review of 15 adverse event reports about the Abbott ID Now device for low sensitivity.[156]

On 21 May, researchers at Ben-Gurion University in Israel reported a one-minute coronavirus test with 90% accuracy, based on the "change in the resonance in the THz spectral range" shown by the coronavirus through THz spectroscopy.[157]

Nearly two million antibody tests imported into Australia and costing $20 million were declared unusable.[158][159][160]

In early May Harvard's Global Health Institute estimated that the US needed to test more than 900k per day.[161][162] Other recommendations ranged up to 23m per day.[163][164][165][166]

On 29 May Siemens received an EUA for its anti-spike RBD-targeting serology test that it believes detects neutralizing antibodies.[167]

By month end, testing had surpassed 1.4m/week.[136]

June

In early June, researchers announced a nucleic acid diagnostic test using reverse transcription-loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP), an existing technology used in pathogenic microorganism identification, genetically modified ingredients, tumor detection, and embryo sex identification. The test identified virus in samples of serum, urine, saliva, oropharyngeal swabs and nasopharyngeal swabs. Once commercialized the test has the potential to provide rapid (30-45 minute) diagnosis at point of care. The test was 100% selective and highly sensitive, detecting virus at a concentration of .06 fg/ml.[168]

As of 14 June 2020, the percentage testing positive in the US as a whole had fallen below 5%.[169] As of late June, test numbers crossed 600k/day.[151]

Testing protocols

Drive-through testing

In drive-through testing, a healthcare professional takes a sample using appropriate precautions, such as wearing PPE.[170][171] Drive-through centers helped South Korea accelerate its testing program.[172]

Home collection

In Hong Kong test subjects can stay home and receive a specimen tube. They spit into it, return it and later get the result.[173]

Pooled testing

In Israel, researchers at Technion and Rambam Hospital developed a method for testing samples from 64 patients simultaneously, by pooling the samples and only testing further if the combined sample was positive.[174][175][176] Pool testing was then adopted in Israel, Germany, South Korea,[177] Nebraska,[178] China[179] and the Indian states of Uttar Pradesh,[180] West Bengal,[181] Punjab,[182] Chhattisgarh[183] and Maharashtra.[184]

Open source, multiplexed designs released by Origami Assays can test as many as 1122 patient samples using only 93 assays.[185] These balanced designs can be run in small laboratories without robotic liquid handlers.

Multi-tiered testing

One study proposed a rapid immune response assay as a screening test, with a confirmatory nucleic acid test for diagnosis, followed by a rapid antibody test to determine course of action and assess population exposure/herd immunity.[186]

Required volume

Required testing levels are a function of disease spread. The more the cases, the more tests are needed to manage the outbreak. COVID-19 tends to grow exponentially at the beginning of an outbreak, meaning that the number of required tests initially also grows exponentially. If properly targeted testing grows more rapidly than cases, it can be contained.

WHO recommends increasing testing until fewer than 10% are positive in any given jurisdiction.[187]

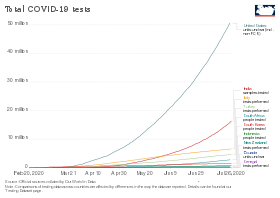

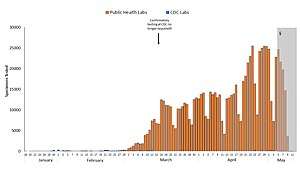

United States

Blue: CDC lab

Orange: Public health lab

Gray: Data incomplete due to reporting lag

Not shown: Testing at private labs; total exceeded 100,000 per day by 27 March.[188]

Economist Paul Romer reported that the US has the technical capacity to scale up to 20 million tests per day, which is his estimate of the scale needed to fully remobilize the economy.[164] The Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics estimated on 4 April that this capacity could be available by late July.[189] Romer pointed to single-molecule real-time sequencing equipment from Pacific Biosciences[190][164] and to the Ion Torrent Next-Generation Sequencing equipment from ThermoFisher Scientific.[191][164] According to Romer, "Recent research papers suggest that any one of these has the potential to scale up to millions of tests per day." This plan requires removing regulatory hurdles. Romer estimated that $100 billion would cover the costs.[164]

Romer also claimed that high test accuracy is not required if tests are administered frequently enough. He ran model simulations in which 7% of the population is tested every day using a test with a 20% false negative rate and a 1% false positive rate. The average person would be tested roughly every two weeks. Those who tested positive would go into quarantine. Romer's simulation indicated that the fraction of the population that is infected at any given time (known as the attack rate) peaks reaches roughly 8% in about thirty days before gradually declining, in most runs reaching zero at 500 days, with cumulative prevalence remaining below 20%.[192]

Available tests

Countries around the world developed tests independently and in partnership with others.

Nucleic acid tests

Tests developed in China, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the US targeted different parts of the viral genome. WHO adopted the German system for manufacturing kits sent to low-income countries without the resources to develop their own.

PowerChek Coronavirus looks for the "E" gene shared by all beta coronaviruses, and the RdRp gene specific to SARS-CoV-2.[193]

.jpg)

Abbott Laboratories' ID Now nucleic acid test uses isothermal amplification technology.[119] The assay amplifies a unique region of the virus's RdRp gene; the resulting copies are then detected with "fluorescently-labeled molecular beacons".[194] The test kit uses the company's "toaster-size" ID Now device, which is widely deployed in the US.[195] The device can be used in laboratories or in point of care settings, and provides results in 13 minutes or less.[194]

Primerdesign offers its Genesig Real-Time PCR Coronavirus (COVID‑19). Cobas SARS-CoV-2 Qualitative assay runs on the Cobas® 6800/8800 Systems by Roche Molecular Systems. They are offered by the United Nations and other procurement agencies.

Antigen tests

Quidel's "Sofia 2 SARS Antigen FIA"[155][43] is a lateral flow test that uses monoclonal antibodies to detect the virus's nucleocapsid (N) protein.[196] The result is read out by the company's Sofia 2 device using immunofluorescence.[196] The test is simpler and cheaper but less accurate than nucleic acid tests. It can be deployed in laboratories or at point of care and gives results in 15 minutes.[155] A false negative result occurs if the sample's antigen level is positive but below the test's detection limit, requiring confirmation with a nucleic acid test.[196]

Serology (antibody) tests

Antibodies are usually detectable 14 days after the onset of the infection. Multiple jurisdictions survey their populations using these tests.[197][198] The test requires a blood draw.

Private US labs including Quest Diagnostics and LabCorp offer antibody testing upon request.[199]

Antibody tests are available in various European countries.[200] Quotient Limited developed a CE marked COVID-19 antibody test. [201][202][203]

Accuracy

Accuracy is measured in terms of specificity and selectivity. Test errors can be false positives (the test is positive, but the virus is not present) or false negatives, (the test is negative, but the virus is present).[205]

Sensitivity and specificity

Sensitivity indicates whether the test accurately identifies whether the virus is present. Each test requires a minimum level of viral load in order to produce a positive result. A 90% sensitive test will correctly identify 90% of infections, missing the other 10% (a false negative). Even relatively high sensitivity rates can produce high rates of false negatives in populations with low incidence rates.[205]

Specificity indicates how well-targeted the test is to the virus in question. Highly specific tests pick up only the virus in question. Non-selective tests pick up other viruses as well. A 90% specific test will correctly identify 90% of those who are uninfected, leaving 10% with a false positive result.[205]

Low-specificity tests have a low positive predictive value (PPV) when prevalence is low. For example, suppose incidence is 5%. Testing 100 people at random using a test that has a specificity of 95% would yield on average 5 people who are actually negative who would incorrectly test positive. Since 5% of the subjects actually are positive, another five would also test positive correctly, totaling 10 positive results. Thus, the PPV is 50%,[206] an outcome no different from a coin toss. In this situation retesting those with a positive result increases the PPV to 94.5%, meaning that only 4.5% of the second tests would return the incorrect result, on average less than 1 incorrect result.[207]

Causes of test error

Improper sample collection, exemplified by failure to acquire enough sample and failure to insert a swab deep into the nose. This results in insufficient viral load, one cause of low clinical sensitivity.

The time course of infection also affects accuracy. Samples may be collected before the virus has had a chance to establish itself or after the body has stopped its progress and begun to eliminate it.

Improper storage for too long a time can cause RNA breakdown and lead to wrong results as viral particles disintegrate.[208]

Improper design and manufacture can yield inaccurate results. Millions of tests made in China were rejected by various countries throughout the period of March 2020 through May 2020.

Test makers typically report the accuracy levels of their tests when seeking approval from authorities. In some jurisdictions, these results are cross-validated by additional assessments. Reported results may not be achieved in clinical settings due to such operational inconsistencies.

PCR-based test

.png)

RT-PCR is the most accurate diagnostic test.[107] It typically has high sensitivity and specificity in a laboratory setting: however, in one study sensitivity dropped to 66-88% clinically.[209]

In one study sensitivity was highest at week one (100%), followed by 89.3%, 66.1%, 32.1%, 5.4% and zero by week six.[210][211]

| Samples from ... | Positive rate |

|---|---|

| Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid specimens | 93% (n=14) |

| Sputum | 72% (n=75) |

| Nasal swabs | 63% (n=5) |

| Fibrobronchoscope brush biopsy | 46% (6/13) |

| Pharyngeal swabs | 32% (n=126) |

| Feces | 29% (n=44) |

| Blood | 1% (n=3) |

A Dutch CDC-led laboratory investigation compared 7 PCR kits.[212] Test kits made by BGI, R-Biopharm AG, BGI, KH Medical and Seegene showed high sensitivity.[213]

High sensitivity kits are recommended to assess people without symptoms, while lower sensitivity tests are adequate when diagnosing symptomatic patients.[212]

Confirmatory testing

The WHO recommends countries that do not have testing capacity and national laboratories with limited experience on COVID‑19 send their first five positives and the first ten negative COVID‑19 samples to one of the 16 WHO reference laboratories for confirmatory testing.[216][217] Out of the sixteen reference laboratories, seven are in Asia, five in Europe, two in Africa, one in North America and one in Australia.[218]

National responses

Iceland

Iceland[219] managed the pandemic with aggressive contact tracing, inbound travel restrictions, testing, and quarantining, but with less aggressive lock-downs.

India

Italy

Researchers tested the entire population of Vò, the site of Italy's first COVID‑19 death. They tested about 3,400 people twice, at an interval of ten days. About half the people testing positive had no symptoms. All discovered cases were quarantined. Along with restricting travel to the commune, new infections were completely eliminated.[220]

Japan

Unlike other Asian countries, Japan did not experience a pandemic of SARS or MERS, so the country's PCR testing system was not well developed.[221][222] Japan preferentially tested patients with severe illness and their close contacts at the beginning. Japan's Novel Coronavirus Expert Meeting chose cluster measures to identify infections clusters.[221][222] The Expert Meeting analyzed the outbreak from Wuhan and identified conditions leading to clusters (closed spaces, crowded spaces and close-contact), and asked people to avoid them.[222][223]

In January, contact tracers took action shortly after the first infection was found. Only administrative tests were carried out at first, until insurance began covering PCR tests on 6 March. Private companies began to test, and the test system gradually expanded.[221][224]

On 3 April, those with positive tests were legally permitted to recuperate at home or in a hotel if they had asymptomatic or mild illness, ending the hospital bed shortage.[225] The first wave (from China) was contained,[226] but a second wave (caused by returnees from Europe and the US) in mid-March led to spreading infection in April.[222] On 7 April, Japan declared a state of emergency, (less strict than a lockdown, because it did not block cities or restrict outings).[222][225][227] On 13 May, antigen test kits became covered by insurance, and were combined with a PCR test for diagnosis.[228][229]

Japan's PCR test count per capita remained far smaller than in some other countries even though its positive test rate was lower. Excess mortality was observed in March.[223][227][230] The Expert Meeting stated, "The Japanese health care system originally carries out pneumonia surveillance, allowing it to detect most of the severely ill patients who develop pneumonia. There are a large number of CT scanners in Japan and they have spread to small hospitals all over the country, so pneumonia patients are rarely missed. In that sense, it meets the same standards as other countries that mainly carry out PCR tests."[223][230] The group recommended using CT scans data and doctor's findings for diagnosis.[231][232] On the Diamond Princess cruise ship, many people who initially tested negative later tested positive. Half of coronavirus-positives there who remained mild or asymptomatic had pneumonia findings on CT scans and their CT image showed a frosted glass shadow that is characteristic of infection.[233][234]

As of July 18, Japan's daily PCR testing capacity was about 32,000, more than three times the 10,000 cases as of April. When the antigen test is added to it, the number is about 58,000. The number of tests per 1,000 people in the United States is about 27 times that of Japan, the UK is 20 times, Italy is 8 times, and South Korea is twice (as of July 26).[235][236][237] The number of those infected with coronavirus and inpatients has increased in July, but the number of serious cases has not increased. This is thought to be due to the proper testing of those infected in July compared to those in April. In April, the number of tests could not catch up with the increase in the number of infected people, and the test standards were strict, so the test positive rate exceeded 30% at the peak. It means that there were quite a few cases where the those infected was not PCR tested. It is thought that the severe case was preferentially tested though there were a lot of mild cases and asymptomatic carriers mainly in the young during the first wave. In other words, it became possible to grasp the actual situation of infection much better than before by strengthening the testing system.[238] At the end of July, accommodation facilities for mild and asymptomatic carriers became full, and the authorities requested hospitals to prepare beds for the mild. However, it became difficult to treat patients with other illnesses and to maintain the ICU system including the staff due to the occupation of hospital beds by patients with mild symptoms.[239][240][241]

Russia

On 27 April, Russia tested 3 million people and had 183,000 positive results.[242] On 28 April Anna Popova, head of Federal Service for Surveillance in Healthcare (Roszdravnadzor) stated that 506 laboratories were testing; that 45% of those who tested positive had no symptoms; that 5% of patients had a severe form; and 40% of infections were from family members. Illness improved from six days to one day after symptoms appeared. Antibody testing was carried out on 3,200 Moscow doctors, finding 20% immunity.[243]

Singapore

With contact tracing, inbound travel restrictions, testing, and quarantining, Singapore arrested the initial spread without complete lockdown.[244]

South Korea

South Korea's broad testing approach helped reduce spread. Testing capacity, largely in private sector labs, was built up over several years by the South Korean government in the early 2000s.[245]

The government exploited the resident registration number (RRN) system. Authorities mobilized young men who were eligible for military service as social service agents, security and public health doctors. Public health doctors were mainly dispatched to public health centers and life treatment centers where mildly ill patients were accommodated. They performed PCR tests and managed mild patients. Social service agents worked in pharmacies to fill staff shortages. Korea's 10k PCR tests per million residents was the world's highest as of 13 April rising to 20k by mid-June. Twenty-seven Korean companies exported test kits worth $48.6 million in March, and were asked to provide test kits or humanitarian assistance by more than 120 countries. Korean authorities set up a treatment center to isolate and manage patients with asymptomatic and minor illnesses in one facility in order to vacate hospital beds for the more severely ill.

Centers were sited mainly at national facilities and corporate training centers. The failure of Korea's MERS quarantine in May 2015 left Korea more prepared for COVID-19 than countries that did not face that pandemic. Then President Park Geun-hye allowed Korean CDC-approved private sector testing for infectious diseases in 2016. Korea already had a system for isolating, testing and treating infectious disease patients separately from others. Patients with respiratory illness but no epidemiological relevance were treated at the National Hospital, and those with epidemiological relevance were treated at selected clinics.[88][246][247][248][249][250][251][252][253]

Korea established a large scale drive-through/walk-through" test testing program. However, the most common method was “mobile examination”. In Daegu City, 54% of samples were collected by 23 March in home or hospital. Collecting samples door-to-door of avoided the risk of travel by possibly infected patients, but required additional staff. Korea solved the problem by drafting more than 2,700 public insurance doctors.[88][249][248]

The government disclosed personal information to the public via KCDC without patient consent. The authorities used digital surveillance to trace possible spread.[246][249][250][252][253][254][255][256][257] [258]

Taiwan

Health insurance IDs and national identification card numbers were used to trace contacts.[259][260][261][262]

United States

New York State

New York State's control measures consisted of PCR tests, stay-at-home measures and strengthening the healthcare system. On 29 February before its first case, the state allowed testing at the Wordsworth Center. They managed to convince the CDC to approve tests at state laboratories and the FDA to approve a test kit. As of 13 March the state was conducting more than 1,000 daily tests, growing to 10,000/day on 19 March. In April, the number exceeded 20,000. Many people queued at hospitals to get tested. On 21 March New York City health officials directed medical providers to test only those entering the hospital, for lack of PPE.[252][263][264][265][266]

USS Theodore Roosevelt

Following an outbreak, 94% of the 4,800 aircraft carrier crew were tested. Roughly 60 percent of the 600-plus sailors who tested positive were asymptomatic.[267] Five infected sailors who completed quarantine subsequently developed flu-like symptoms and again tested positive.[268]

Delayed testing

A shortage of trained medical laboratory scientists, assay reagents, analyzers, transport medium, and PPE coupled with high demand had limited initially limited the availability of testing and led to significantly increased turnaround times.

Testing statistics by country

Testing strategies vary by country and over time,[269] with some countries testing very widely,[7] while others have at times focused narrowly on only testing the seriously ill.[270] The country that tests only people showing symptoms will have a higher figure for "% (Confirmed cases as percentage of tested samples or tested cases)" than the country that also tests others.[271] If two countries are alike in every respect, including which people they test, the one that tests more people will have a higher "Confirmed / million people". Studies have also found that countries that test more, relative to the number of deaths, have lower estimated case fatality rates[8] and younger age distributions of cases.[10]

| Country | Date[lower-alpha 1] | Tested | Units[lower-alpha 2] | Confirmed (cases) |

% | Tested / million people |

Confirmed / million people |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 August | 97,199 | samples | 36,542 | 41.3 | 2,274 | 939 | [272] | |

| 7 August | 44,881 | samples | 6,151 | 13.7 | 15,676 | 2,148 | [273] | |

| 5 August | 79,981 | samples | 32,499 | 40.6 | 1,834 | 745 | [274] | |

| 29 July | 675,011 | samples | 173,355 | 25.7 | 14,875 | 3,820 | [275] | |

| 13 August | 180,497 | samples | 41,023 | 22.7 | 61,149 | 13,898 | [276] | |

| 16 August | 5,297,558 | samples | 23,288 | 0.44 | 210,221 | 924 | [277] | |

| 15 August | 1,009,354 | 23,124 | 2.3 | 113,377 | 2,597 | [278] | ||

| 13 August | 812,033 | samples | 33,915 | 4.2 | 82,040 | 3,426 | [279] | |

| 12 August | 933,762 | samples | 45,264 | 4.8 | 594,963 | 28,841 | [280] | |

| 12 August | 1,328,757 | samples | 271,881 | 20.5 | 8,068 | 1,651 | [281] | |

| 30 July | 10,881 | 143 | 1.3 | 37,910 | 498 | [282] | ||

| 23 July | 1,219,705 | samples | 66,688 | 5.5 | 128,501 | 7,026 | [283] | |

| 7 August | 1,346,748 | samples | 72,016 | 5.3 | 116,948 | 6,254 | [284] | |

| 7 August | 55,354 | samples | 113 | 0.20 | 74,631 | 152 | [285] | |

| 29 July | 144,153 | cases | 73,534 | 51.0 | 12,614 | 6,434 | [286] | |

| 10 August | 152,346 | samples | 14,498 | 9.5 | 44,526 | 4,237 | [287] | |

| 13 August | 13,464,336 | samples | 3,224,876 | 24.0 | 64,071 | 15,346 | [288][289] | |

| 15 August | 330,785 | samples | 14,243 | 4.3 | 47,595 | 2,049 | [290] | |

| 29 July | 17,400 | samples | 1,213 | 7.0 | 832 | 58 | [291][292] | |

| 16 July | 135,000 | samples | 16,157 | 12.0 | 5,086 | 609 | [293] | |

| 12 August | 4,581,083 | samples | 120,844 | 2.6 | 120,889 | 3,189 | [294] | |

| 12 August | 1,908,964 | samples | 378,168 | 19.8 | 100,097 | 19,829 | [295] | |

| 31 July | 160,000,000 | samples | 91,418 | 0.06 | 111,163 | 64 | [296][297][298][299] | |

| 13 August | 2,063,332 | samples | 433,805 | 21.0 | 42,756 | 8,989 | [300] | |

| 7 August | 102,257 | samples | 22,081 | 21.6 | 20,454 | 4,417 | [301] | |

| 5 August | 124,383 | cases | 5,376 | 4.3 | 30,514 | 1,319 | [302] | |

| 28 July | 256,996 | samples | 2,588 | 1.0 | 22,690 | 228 | [303] | |

| 12 August | 243,405 | samples | 1,291 | 0.53 | 281,959 | 1,495 | [304] | |

| 5 August | 722,003 | samples | 17,529 | 2.4 | 67,515 | 1,639 | [305] | |

| 12 August | 1,874,640 | samples | 15,419 | 0.8 | 315,966 | 2,599 | [306] | |

| 28 July | 44,051 | 8,873 | 20.1 | 492 | 99 | [307] | ||

| 13 August | 276,491 | samples | 98,343 | 35.6 | 16,184 | 5,756 | [308] | |

| 29 July | 449,968 | samples | 93,356 | 20.7 | 4,496 | 933 | [307] | |

| 14 August | 273,509 | samples | 22,314 | 8.2 | 42,168 | 3,440 | [309] | |

| 14 August | 132,270 | samples | 2,177 | 1.6 | 99,574 | 1,639 | [310] | |

| 19 July | 331,366 | samples | 10,207 | 3.1 | 2,882 | 89 | [311] | |

| 13 August | 453,576 | samples | 7,700 | 1.7 | 81,825 | 1,389 | [312] | |

| 21 July | 3,510,897 | 177,338 | 5.1 | 52,384 | 2,646 | [313][314][315] | ||

| 29 July | 8,006,135 | samples | 206,926 | 2.6 | 96,286 | 2,489 | [316] | |

| 20 July | 344,137 | 27,667 | 8.0 | 11,075 | 890 | [274] | ||

| 19 July | 410,766 | samples | 4,007 | 0.98 | 38,145 | 372 | [317] | |

| 18 June | 5,465 | samples | 24 | 0.44 | 49,034 | 215 | [318] | |

| 19 July | 36,254 | cases | 6,544 | 18.1 | 2,761 | 498 | [274] | |

| 8 August | 358,437 | samples | 4,653 | 1.3 | 37,104 | 482 | [319] | |

| 12 August | 168,233 | samples | 1,972 | 1.2 | 461,849 | 5,414 | [320] | |

| 16 August | 29,309,703 | samples | 2,589,682 | 8.8 | 21,241 | 1,877 | [321][322] | |

| 16 August | 1,888,215 | samples | 139,549 | 7.4 | 6,894 | 510 | [323] | |

| 7 August | 2,637,575 | samples | 322,567 | 12.2 | 31,708 | 3,878 | [324] | |

| 20 July | 809,522 | samples | 94,693 | 11.7 | 20,126 | 2,354 | [325] | |

| 14 August | 699,036 | samples | 26,995 | 3.9 | 142,037 | 5,485 | [326] | |

| 13 August | 2,026,261 | 88,733 | 4.4 | 220,845 | 9,671 | [327] | ||

| 2 August | 6,916,765 | samples | 248,070 | 3.6 | 114,593 | 4,110 | [328] | |

| 28 July | 87,683 | 15,713 | 17.9 | 3,324 | 596 | [274] | ||

| 28 July | 37,210 | samples | 855 | 2.3 | 13,655 | 314 | [329] | |

| 16 August | 1,164,029 | 53,557 | 4.6 | 9,227 | 425 | [330] | ||

| 13 August | 2,252,153 | samples | 101,372 | 4.5 | 120,736 | 5,434 | [331] | |

| 18 July | 238,163 | samples | 12,750 | 5.4 | 5,007 | 268 | [332] | |

| 9 June | 17,199 | samples | 1,269 | 7.4 | 9,500 | 701 | [333] | |

| 16 July | 252,549 | samples | 12,498 | 4.9 | 39,526 | 1,956 | [334][335] | |

| 14 August | 222,531 | samples | 1,308 | 0.59 | 115,903 | 681 | [336] | |

| 14 August | 401,016 | 8,045 | 2.0 | 58,753 | 1,179 | [337] | ||

| 5 August | 55,899 | cases | 4,224 | 7.6 | 8,144 | 615 | [307] | |

| 13 August | 565,782 | samples | 2,330 | 0.41 | 202,475 | 834 | [338] | |

| 14 August | 555,003 | samples | 6,071 | 1.1 | 886,433 | 9,696 | [339] | |

| 5 August | 45,634 | cases | 12,222 | 26.8 | 1,738 | 465 | [307] | |

| 7 August | 34,051 | samples | 4,575 | 13.4 | 1,780 | 239 | [340] | |

| 26 July | 937,645 | cases | 8,897 | 0.9 | 28,611 | 271 | [341] | |

| 7 August | 86,651 | samples | 4,769 | 5.5 | 220,782 | 12,151 | [342] | |

| 12 August | 147,411 | samples | 1,190 | 0.81 | 298,669 | 2,411 | [343] | |

| 2 June | 120,358 | samples | 344 | 0.29 | 95,071 | 272 | [344] | |

| 13 August | 1,058,970 | cases | 505,751 | 47.8 | 8,231 | 3,931 | [345] | |

| 13 July | 118,335 | samples | 19,382 | 16.4 | 44,817 | 7,341 | [346] | |

| 4 August | 24,469 | cases | 3,361 | 13.7 | 38,765 | 5,325 | [347] | |

| 7 August | 1,405,159 | cases | 21,548 | 1.5 | 38,069 | 584 | [348] | |

| 14 August | 75,430 | samples | 2,708 | 3.6 | 2,413 | 87 | [349] | |

| 31 July | 112,381 | samples | 361 | 0.32 | 2,065 | 6.6 | [350] | |

| 7 August | 731,977 | samples | 21,750 | 3.0 | 26,053 | 774 | [351] | |

| 4 August | 668,851 | cases | 55,955 | 8.4 | 38,385 | 3,211 | [352] | |

| 16 August | 571,942 | samples | 1,271 | 0.22 | 114,765 | 255 | [353] | |

| 30 July | 276,053 | samples | 42,689 | 15.5 | 1,349 | 209 | [354] | |

| 19 June | 922 | cases | 0 | 0 | 36 | 0 | [355] | |

| 8 August | 113,537 | samples | 11,771 | 10.4 | 54,660 | 5,667 | [356] | |

| 19 July | 56,268 | 1702 | 3.02 | 172,601 | 5,221 | [357] | ||

| 14 August | 530,446 | cases | 9,850 | 1.9 | 98,824 | 1,835 | [358] | |

| 1 July | 194,945 | samples | 41,194 | 21.1 | 41,947 | 8,864 | [359] | |

| 14 August | 2,229,409 | samples | 287,300 | 12.9 | 10,096 | 1,301 | [360] | |

| 9 August | 216,765 | samples | 18,654 | 8.6 | 42,907 | 3,692 | [361] | |

| 13 August | 261,350 | samples | 78,446 | 30.0 | 62,571 | 18,781 | [362] | |

| 13 August | 146,284 | samples | 8,389 | 5.7 | 20,509 | 1,176 | [363] | |

| 14 August | 2,705,122 | samples | 516,296 | 19.1 | 82,412 | 15,729 | [364] | |

| 14 August | 2,003,599 | samples | 153,660 | 7.7 | 19,841 | 1,522 | [365] | |

| 25 July | 2,095,222 | samples | 42,622 | 2.0 | 54,583 | 1,110 | [366] | |

| 13 August | 1,783,267 | samples | 53,548 | 3.0 | 173,527 | 5,211 | [367] | |

| 12 August | 533,995 | samples | 113,938 | 21.3 | 185,347 | 39,547 | [368] | |

| 14 August | 1,478,056 | samples | 68,046 | 4.6 | 76,182 | 3,507 | [369] | |

| 15 August | 32,533,818 | samples | 922,853 | 2.8 | 221,703 | 6,289 | [370][371] | |

| 29 July | 255,959 | 1,963 | 0.77 | 19,762 | 152 | [372] | ||

| 14 August | 4,521 | samples | 25 | 0.6 | 24,856 | 137 | [373] | |

| 12 August | 4,138,204 | samples | 295,902 | 7.2 | 118,867 | 8,500 | [374] | |

| 26 July | 104,061 | 9,681 | 9.3 | 6,564 | 611 | [375] | ||

| 4 August | 703,246 | cases | 26,738 | 3.8 | 100,986 | 3,840 | [376] | |

| 3 August | 1,474,372 | samples | 53,051 | 3.6 | 258,498 | 9,301 | [377][378] | |

| 12 August | 284,111 | samples | 2,690 | 0.95 | 52,055 | 493 | [379] | |

| 12 August | 140,942 | samples | 2,332 | 1.7 | 67,306 | 1,114 | [380] | |

| 14 August | 3,351,111 | cases | 579,140 | 17.3 | 56,503 | 9,765 | [381] | |

| 16 August | 1,681,787 | cases | 15,318 | 0.91 | 32,524 | 296 | [382] | |

| 13 August | 7,472,031 | samples | 337,334 | 4.5 | 159,888 | 7,218 | [383][384] | |

| 14 August | 182,681 | samples | 2,886 | 1.6 | 8,430 | 133 | [385] | |

| 23 July | 31,805 | samples | 11,302 | 35.5 | 725 | 258 | [307] | |

| 5 July | 597,850 | cases | 72,693 | 12.2 | 57,889 | 7,039 | [386] | |

| 7 August | 854,885 | samples | 37,169 | 4.4 | 96,316 | 4,213 | [387] | |

| 13 August | 84,016 | samples | 481 | 0.57 | 3,559 | 20 | [388] | |

| 6 June | 2,680 | 509 | 19.0 | 45 | 8.5 | [274] | ||

| 28 July | 749,213 | samples | 3,356 | 0.48 | 10,126 | 48 | [389] | |

| 14 August | 12,937 | samples | 426 | 3.3 | 9,485 | 312 | [390] | |

| 5 August | 102,041 | cases | 1,656 | 1.6 | 8,634 | 140 | [391] | |

| 9 August | 5,263,816 | samples | 240,804 | 4.6 | 63,301 | 2,896 | [392] | |

| 14 August | 312,792 | samples | 1,385 | 0.44 | 6,838 | 30 | [393] | |

| 29 July | 998,299 | samples | 67,597 | 6.8 | 23,752 | 1,608 | [394] | |

| 12 August | 5,700,145 | samples | 63,212 | 1.1 | 593,805 | 6,585 | [395] | |

| 14 August | 14,142,736 | samples | 316,367 | 2.2 | 209,380 | 4,684 | [396] | |

| 12 August | 63,715,571 | samples | 5,172,216 | 8.1 | 192,502 | 15,627 | [397][398] | |

| 30 July | 110,951 | samples | 1,243 | 1.1 | 31,970 | 358 | [399] | |

| 14 July | 1,400,000 | samples | 13,872 | 0.99 | 41,132 | 408 | [400] | |

| 17 July | 1,420,066 | samples | 11,891 | 0.84 | 49,159 | 412 | [401] | |

| 15 August | 723,596 | samples | 962 | 0.13 | 7,330 | 9.7 | [402] | |

| 30 July | 129,899 | samples | 3,092 | 2.38 | 8,740 | 208 | [403] | |

| ||||||||

See also

References

- CDC (11 February 2020). "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Kobokovich A, West R, Gronvall G. "Global Progress on COVID-19 Serology-Based Testing". Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- "Test for Past Infection – CDC". CDC.gov. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 16 May 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

Antibody blood tests, also called antibody tests, check your blood by looking for antibodies, which show if you had a previous infection with the virus. Depending on when someone was infected and the timing of the test, the test may not find antibodies in someone with a current COVID-19 infection.

- Abbasi J (April 2020). "The Promise and Peril of Antibody Testing for COVID-19". JAMA. JAMA Network. 323 (19): 1881. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6170. PMID 32301958. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- Brotschi M (7 March 2020). "Bund sucht nicht mehr alle Corona-Infizierten". Der Bund (in German). ISSN 0774-6156. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Van Beusekom, Mary (24 March 2020). "Italian doctors note high COVID-19 death rate, urge action". CIDRAP News. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Otmani M (22 March 2020). "COVID-19: First results of the voluntary screening in Iceland". Nordic Life Science – the leading Nordic life science news service. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Ward, D. (April 2020) "Sampling Bias: Explaining Wide Variations in COVID-19 Case Fatality Rates". WardEnvironment. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.24953.62564/1

- Henriques M (2 April 2020). "Coronavirus: Why death and mortality rates differ". BBC News. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Ward D (May 2020). Sampling Bias: Explaining Variations in Age Distributions of COVID-19 Cases. Technical Report (Report). WardEnvironment. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.27321.19047/2.

- "Siouxsie Wiles & Toby Morris: What we don't know about Covid-19". The Spinoff. 6 May 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "Testing for COVID-19 – CDC". CDC.gov. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 20 May 2020. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

Two kinds of tests are available for COVID-19: viral tests and antibody tests.

- "RNA Extraction". AssayGenie. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- "How is the COVID-19 Virus Detected using Real Time RT-PCR?". IAEA. 27 March 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "Curetis Group Company Ares Genetics and BGI Group Collaborate to Offer Next-Generation Sequencing and PCR-based Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Testing in Europe". GlobeNewswire News Room. 30 January 2020. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, et al. (April 2009). "The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments". Clinical Chemistry. 55 (4): 611–22. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. PMID 19246619.

- "Real-time reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) and its potential use in clinical diagnosis" (PDF). Clinical Science. 23 September 2005. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "The Basics: RT-PCR". ThermoFisher Scientific. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Kang XP, Jiang T, Li YQ, Lin F, Liu H, Chang GH, et al. (June 2010). "A duplex real-time RT-PCR assay for detecting H5N1 avian influenza virus and pandemic H1N1 influenza virus". Virology Journal. 7: 113. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-7-113. PMC 2892456. PMID 20515509.

- Joyce C (2002). Quantitative RT-PCR. A review of current methodologies. Methods Mol. Biol. 193. pp. 83–92. doi:10.1385/1-59259-283-X:083. ISBN 978-1-59259-283-8. PMID 12325527.

- Varkonyi-Gasic E, Hellens RP (2010). "qRT-PCR of Small RNAs". Plant Epigenetics. Methods in Molecular Biology. 631. pp. 109–22. doi:10.1007/978-1-60761-646-7_10. ISBN 978-1-60761-645-0. PMID 20204872.

- "Accelerated Emergency Use Authorization (Eua) Summary Covid-19 Rt-Pcr Test (Laboratory Corporation of America)". FDA. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- Taylor S, Wakem M, Dijkman G, Alsarraj M, Nguyen M (April 2010). "A practical approach to RT-qPCR-Publishing data that conform to the MIQE guidelines". Methods. 50 (4): S1-5. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.01.005. PMID 20215014.

- Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, et al. (April 2009). "The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments". Clinical Chemistry. 55 (4): 611–22. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. PMID 19246619.

- "Real-Time RT-PCR Panel for Detection 2019-nCoV". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 29 January 2020. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- Drosten C (26 March 2020). "Coronavirus-Update Folge 22" (PDF). NDR. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 March 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Here's where things stand on COVID-19 tests in the U.S." ScienceNews. 17 April 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Xu R, Cui B, Duan X, Zhang P, Zhou X, Yuan Q (April 2020). "Saliva: potential diagnostic value and transmission of 2019-nCoV". International Journal of Oral Science. 12 (1): 11. doi:10.1038/s41368-020-0080-z. PMC 7162686. PMID 32300101.

- Drosten C, Günther S, Preiser W, van der Werf S, Brodt HR, Becker S, et al. (May 2003). "Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine. 348 (20): 1967–76. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa030747. PMID 12690091.

- "COVID-19 saliva tests: What is the benefit?". Mayo Clinic. 16 April 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "New Rutgers Saliva Test for Coronavirus Gets FDA Approval". Rutgers.edu. 13 April 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "FDA authorizes Covid-19 saliva test for emergency use". CNN. 14 April 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Yale University School of Public Health finds saliva samples promising alternative to nasopharyngeal swab". Merck Manual. 29 April 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- "FDA gives emergency approval to 'game changer' COVID-19 saliva test". Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Symptom-Based Strategy to Discontinue Isolation for Persons with COVID-19 (2020) referenced

- CDC unpublished data

- COVID-19 Investigation Team (June 2020). "Clinical and virologic characteristics of the first 12 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States". Nature Medicine. 26 (6): 861–868. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0877-5. PMID 32327757.

- Young BE, Ong SW, Kalimuddin S, Low JG, Tan SY, Loh J, et al. (March 2020). "Epidemiologic Features and Clinical Course of Patients Infected With SARS-CoV-2 in Singapore". JAMA. 323 (15): 1488. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.3204. PMC 7054855. PMID 32125362.

- Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, Liang L, Huang H, Hong Z, et al. (March 2020). "SARS-CoV-2 Viral Load in Upper Respiratory Specimens of Infected Patients". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (12): 1177–1179. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2001737. PMC 7121626. PMID 32074444.

- Wölfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, Seilmaier M, Zange S, Müller MA, et al. (May 2020). "Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019". Nature. 581 (7809): 465–469. Bibcode:2020Natur.581..465W. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. PMID 32235945.

- Zimmer C (5 May 2020). "With Crispr, a Possible Quick Test for the Coronavirus". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- "STOPCovid". stopcovid.science. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- Joung J, Ladha A, Saito M, Segel M, Bruneau R, Huang MW, et al. (May 2020). "Point-of-care testing for COVID-19 using SHERLOCK diagnostics". MedRxiv: 2020.05.04.20091231. doi:10.1101/2020.05.04.20091231. PMC 7273289. PMID 32511521.

- "Developing Antibodies and Antigens for COVID-19 Diagnostics". Technology Networks. 6 April 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- "NIH launches competition to speed COVID-19 diagnostics". AAAS. 29 April 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Remarks by President Trump, Vice President Pence, and Members of the Coronavirus Task Force in Press Briefing April 17, 2020". Whitehouse.gov. 17 April 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- "What to know about the three main types of coronavirus tests". CNN. 29 April 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- Office of the Commissioner (9 May 2020). "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes First Antigen Test to Help in the Rapid Detection of the Virus that Causes COVID-19 in Patients". FDA.

- Salehi S, Abedi A, Balakrishnan S, Gholamrezanezhad A (March 2020). "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Systematic Review of Imaging Findings in 919 Patients". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 215 (1): 87–93. doi:10.2214/AJR.20.23034. PMID 32174129.

Known features of COVID-19 on initial CT include bilateral multilobar ground-glass opacification (GGO) with a peripheral or posterior distribution, mainly in the lower lobes and less frequently within the right middle lobe.

- Lee EY, Ng MY, Khong PL (April 2020). "COVID-19 pneumonia: what has CT taught us?". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 20 (4): 384–385. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30134-1. PMC 7128449. PMID 32105641.

- "ACR Recommendations for the use of Chest Radiography and Computed Tomography (CT) for Suspected COVID-19 Infection". American College of Radiology. 22 March 2020. Archived from the original on 13 May 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- "The next frontier in coronavirus testing: Identifying the full scope of the pandemic, not just individual infections". STAT. 27 March 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- Deeks, Jonathan J.; Dinnes, Jacqueline; Takwoingi, Yemisi; Davenport, Clare; Spijker, René; Taylor-Phillips, Sian; Adriano, Ada; Beese, Sophie; Dretzke, Janine; Ferrante di Ruffano, Lavinia; Harris, Isobel M. (25 June 2020). "Antibody tests for identification of current and past infection with SARS-CoV-2". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6: CD013652. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013652. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 32584464.

- "What Immunity to COVID-19 Really Means". Scientific American. 10 April 2020. Archived from the original on 28 April 2020.

- "Cellex Emergency Use Authorization". FDA. 1 April 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "Will an Antibody Test Allow Us to Go Back to School or Work?". New York Times. 10 April 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- "Mount Sinai Emergency Use Authorization". FDA. 15 April 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "Global Progress on COVID-19 Serology-Based Testing". Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- "A SARS-CoV-2 surrogate virus neutralization test (sVNT) based on antibody-mediated blockage of ACE2-spike (RBD) protein-protein interaction". Research Square. 23 April 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- "Will antibody tests for the coronavirus really change everything?". Nature. 18 April 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- "Q&A on COVID-19 Antibody Tests". factcheck.org. 27 April 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- "Neutralising antibody". Biology-Online. 2008. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- Schmaljohn AL (July 2013). "Protective antiviral antibodies that lack neutralizing activity: precedents and evolution of concepts". Current HIV Research. 11 (5): 345–53. doi:10.2174/1570162x113116660057. PMID 24191933.

- "Virus neutralization by antibodies". Virology Blog. 24 July 2009. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- "expert reaction to announcement by Roche of its new serology test for COVID-19 antibodies". Science Media Centre. 17 April 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- Cao WC, Liu W, Zhang PH, Zhang F, Richardus JH (September 2007). "Disappearance of antibodies to SARS-associated coronavirus after recovery". The New England Journal of Medicine. NEJM. 357 (11): 1162–3. doi:10.1056/NEJMc070348. PMID 17855683.

- "Lack of Peripheral Memory B Cell Responses in Recovered Patients with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome: A Six-Year Follow-Up Study" (PDF). Journal of Immunology. 19 April 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- Leslie M (May 2020). "T cells found in coronavirus patients 'bode well' for long-term immunity". Science. 368 (6493): 809–810. Bibcode:2020Sci...368..809L. doi:10.1126/science.368.6493.809. PMID 32439770. S2CID 218834495.

- Symptom-Based Strategy to Discontinue Isolation for Persons with COVID-19 (2020) referenced

- CDC unpublished data

- Young et al. (2020)

- Symptom-Based Strategy to Discontinue Isolation for Persons with COVID-19 (2020) referenced

- CDC unpublished data

- Midgley et al. (2020)

- "What Is R0? Gauging Contagious Infections". Healthline.

- He X, Lau EH, Wu P, Deng X, Wang J, Hao X, et al. (May 2020). "Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19". Nature Medicine. 26 (5): 672–675. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5. PMID 32296168.

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 29 April 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Fraser C, Donnelly CA, Cauchemez S, Hanage WP, Van Kerkhove MD, Hollingsworth TD, et al. (June 2009). "Pandemic potential of a strain of influenza A (H1N1): early findings". Science. 324 (5934): 1557–61. Bibcode:2009Sci...324.1557F. doi:10.1126/science.1176062. PMC 3735127. PMID 19433588.Free text

- "COVID-19 Infections Tracker". COVID-19 Projections Using Machine Learning. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- "About covid19-projections.com". COVID-19 Projections Using Machine Learning. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- "People with COVID-19 may be infectious days before symptoms: study". medicalxpress.com. 15 April 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- "50 Percent of People with COVID-19 Aren't Aware They Have Virus". Healthline. 24 April 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- "Symptom-Based Strategy to Discontinue Isolation for Persons with COVID-19". CDC. 3 May 2020. Archived from the original on 4 May 2020.

- Symptom-Based Strategy to Discontinue Isolation for Persons with COVID-19 (2020) referenced

- CDC unpublished data

- Wölfel et al. (2020)

- Arons MM, Hatfield KM, Reddy SC, Kimball A, James A, Jacobs JR, et al. (May 2020). "Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infections and Transmission in a Skilled Nursing Facility". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (22): 2081–2090. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2008457. PMC 7200056. PMID 32329971.

- Symptom-Based Strategy to Discontinue Isolation for Persons with COVID-19 (2020) referenced

- CDC unpublished data

- Midgley et al. (2020)

- Wölfel et al. (2020)

- Symptom-Based Strategy to Discontinue Isolation for Persons with COVID-19 (2020) referenced Xiao AT, Tong YX, Zhang S (April 2020). "Profile of RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2: a preliminary study from 56 COVID-19 patients". Clinical Infectious Diseases. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa460. PMC 7188124. PMID 32306036.

- Roser M, Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E (4 March 2020). "Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) – Statistics and Research". Our World in Data – via ourworldindata.org.

- Schnirring, Lisa (11 January 2020). "China releases genetic data on new coronavirus, now deadly". CIDRAP. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- Schnirring, Lisa (13 January 2020). "Thailand finds Wuhan novel coronavirus in traveler from China". CIDRAP. Archived from the original on 13 January 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- Shu, Yuelong; McCauley, John (2017). "GISAID: Global initiative on sharing all influenza data – from vision to reality". Eurosurveillance. 22 (13). doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.13.30494. PMC 5388101. PMID 28382917.

- "Laboratory Readiness for Detecting the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infection in Malaysia". Director-General of Health, Malaysia. 9 February 2020.

- "Malaysia must ramp up testing". The Star Malaysia. 26 March 2020.

- "BGI Sequencer, Coronavirus Molecular Assays Granted Emergency Use Approval in China". GenomeWeb. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- "UK defends coronavirus response after Reuters investigation". Reuters. 9 April 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

After developing a test for the new virus by Jan. 10

- "COVID-19 virus testing in NHS laboratories" (PDF). NHS England and NHS Improvement. 16 March 2020.

- "PHE novel coronavirus diagnostic test rolled out across UK". GOV.UK. Retrieved 30 March 2020; "'Increased likelihood' of China virus reaching UK". BBC News. 23 January 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020; "PHE tells patients with suspected coronavirus to call GP or NHS 111". The Pharmaceutical Journal. 27 January 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- "日本が韓国の新型コロナウイルス対策から学べること──(1)検査体制". Newsweek Japan (in Japanese). 2 April 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Sheridan C (April 2020). "Coronavirus and the race to distribute reliable diagnostics". Nature Biotechnology. 38 (4): 382–384. doi:10.1038/d41587-020-00002-2. PMID 32265548.

- "CDC Diagnostic Test for COVID-19". CDC.gov. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- "PolitiFact – Biden falsely says Trump administration rejected WHO coronavirus test kits (that were never offered)". @politifact.

- Совещание по вопросам развития ситуации с коронавирусной инфекцией и мерам по её профилактике

- Transcript for the CDC Telebriefing Update on COVID-19, 28 February 2020

- Jeong S (28 February 2020). "Korea approves 2 more COVID-19 detection kits for urgent use". Korea Biomedical Review. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- "Wuhan Test Lab Opens; CDC Ships Diagnostic Kits: Virus Update". Bloomberg. 5 February 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- "China virus crisis deepens as whistleblower doctor dies". AFP.com. 27 February 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- 日检测量达万份的"火眼"实验室连夜试运行.

- "BGI's Coronavirus Response? Build a Lab in Wuhan". GEN – Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News. 12 February 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- "В России зарегистрирована отечественная тест-система для определения коронавируса". Interfax-Russia.ru. 14 February 2020.

- "COVID-19 Local Laboratory Solution". BGI – Global. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- "'Test, Test, Test': WHO Chief's Coronavirus Message to World". The New York Times. 16 March 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- "'Test, test, test': WHO calls for more coronavirus testing – video". The Guardian. 16 March 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- "Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: increased transmission in the EU/EEA and the UK –seventh update" (PDF). European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 25 March 2020. pp. 15–16. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

the current shortages of laboratory consumables and reagents affect diagnostic capacity and hamper the epidemic response at the national and local levels. The laboratories have experienced delayed or missing deliveries of swabbing material, plastic consumables, RNA extraction and RT-PCR reagents, and PPE. This is affecting laboratories in all EU/EEA countries.

- Baird RP (24 March 2020). "Why Widespread Coronavirus Testing Isn't Coming Anytime Soon". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

South Dakota, said that her state's public-health laboratory—the only lab doing COVID-19 testing in the state—had so much trouble securing reagents that it was forced to temporarily stop testing altogether. also noted critical shortages of extraction kits, reagents, and test kits

- Ossola A (25 March 2020). "Here are the coronavirus testing materials that are in short supply in the US". Quartz. Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

extract the virus's genetic material—in this case, RNA—using a set of chemicals that usually come in pre-assembled kits. 'The big shortage is extraction kits' There are no easy replacements here: 'These reagents that are used in extraction are fairly complex chemicals. They have to be very pure, and they have to be in pure solution'

- Plumbo G. "Mayo Clinic develops test to detect COVID-19 infection". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- Chen, Lulu Yilun (16 March 2020). "Heartbreak in the Streets of Wuhan". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Wang W, Xu Y, Gao R, Lu R, Han K, Wu G, Tan W (March 2020). "Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in Different Types of Clinical Specimens". JAMA. 323 (18): 1843–1844. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.3786. PMC 7066521. PMID 32159775.

- "Comparing RT-PCR and Chest CT for Diagnosing COVID-19". HCPLive®. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "LabCorp Launches Test for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) | Laboratory Corporation of America Holdings". ir.labcorp.com. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "Covid19 : COVID-19". questdiagnostics.com.

- Stein R (3 April 2020). "Coronavirus Testing Backlogs Continue As Laboratories Struggle To Keep Up With Demand". NPR.org. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- Mandavilli A, Edmondson C (25 May 2020). "'This Is Not the Hunger Games': National Testing Strategy Draws Concerns". The New York Times.

- "Hologic's Molecular Test for the Novel Coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, Receives FDA Emergency Use Authorization". Hologic. 16 March 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- "Emergency Use Authorization". FDA. 30 April 2020. Archived from the original on 29 April 2020.

- "FDA Approves Abbott Laboratories Coronavirus Test, Company To Ship 150,000 Kits". IBTimes.com. 19 March 2020. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020.

- "Sunnyvale company wins FDA approval for first rapid coronavirus test with 45-minute detection time". EastBayTimes.com. 21 March 2020. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020.

- "Xpert® Xpress SARS-CoV-2 has received FDA Emergency Use Authorization". cepheid.com. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- "Letter from FDA". FDA. 27 March 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Sullivan H, Rawlinson K, Gayle D, Topping A, Mohdin A, Willsher K, Wintour P, Wearden G, Greenfield P (31 March 2020). "Global confirmed virus death toll passes 40,000 – as it happened". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- "VIDEO: UAE sets up COVID-19 detection lab in just 14 days". Gulf Today. 31 March 2020.

- "Daily COVID-19 tests per thousand people". Our World in Data. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- "Total tests for COVID-19 per 1,000 people". Our World in Data. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- "Covid-19 – Tests auf das Coronavirus: Wann, wo und wie?". Deutschlandfunk (in German). 19 March 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Charisius H (26 March 2020). "Covid-19: Wie gut testet Deutschland?" (in German). Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 Daily Situation Report of the Robert Koch Institute" (PDF). Robert Koch Institute. 26 March 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- "80% of Rapid COVID-19 Tests the Czech Republic Bought From China are Wrong". Prague Morning. 26 March 2020.

- Blažek V (23 March 2020). "Úřad dopředu psal, kdy mohou rychlotesty selhat. I tak je stát nasadil". Zeznam Zprávy (in Czech). Retrieved 7 April 2020.

Indeed, the rapid tests that arrived from China a few days ago do not really reliably detect the infection at an early stage.

- DUDIK, ANDREA; TOMEK, RADOSLAV (1 April 2020). "Europe turned to China for coronavirus testing help. Why some are now regretting it". Fortune. Retrieved 28 June 2020.