British Army during the Napoleonic Wars

The British Army during the Napoleonic Wars experienced a time of rapid change. At the beginning of the French Revolutionary Wars in 1793, the army was a small, awkwardly administered force of barely 40,000 men.[1] By the end of the period, the numbers had vastly increased. At its peak, in 1813, the regular army contained over 250,000 men.[2] The British infantry was "the only military force not to suffer a major reverse at the hands of Napoleonic France."[3]

.png) |

| British Army of the British Armed Forces |

|---|

| Components |

|

| Administration |

| Overseas |

| Personnel |

|

| Equipment |

| History |

| United Kingdom portal |

Structure

In 1793, shortly before Britain became involved in the French Revolutionary Wars, the army consisted of three regiments of Household Cavalry, 27 line regiments of cavalry, seven battalions in three regiments of Foot Guards and 81 battalions in 77 numbered regiments of line infantry, with two colonial corps (one in New South Wales and one in Canada). There were 36 Independent Companies of Invalids, known by their Captain's name, scattered in garrisons and forts across Great Britain.

Administered separately by the Board of Ordnance, the artillery had 40 companies in four battalions of Foot Artillery, 10 companies in the Invalid Battalion, two independent companies in India and a Company of Cadets. Two troops of the Royal Horse Artillery were being organised. The Corps of Royal Engineers and Invalid Corps of Royal Engineers were specialised bodies of officers. The Corps of Royal Military Artificers consisted of six companies. There were also two Independent Companies of Artificers.

There was no formal command structure, and a variety of government departments controlled army units depending on where they were stationed; troops in Ireland were controlled by the Irish establishment, rather than the War Office in London, for example. In 1793, the first steps towards formal organisation were taken when fifteen general officers were appointed to command military districts in England and Wales.[4]

Recruitment

During the later part of the 18th century Britain was divided into three recruiting areas—with England and Wales generally called South Britain—which were further divided into Districts with their own Headquarters. Ireland had separate Districts and organisation, and Scotland, or North Britain, was one administrative area. Home defence, enforcement of law and maintenance of order was primarily the responsibility of the Militia, the Royal Veteran Battalions, the Yeomanry and the Fencibles. Another structure of Recruiting Districts and Sub-Divisions existed alongside this.

The British Army drew many of its raw recruits from the lowest classes of Britain. Since army life was known to be harsh, and the remuneration low, it attracted mainly those for whom civilian life was worse. The Duke of Wellington himself said that many of the men "enlist from having got bastard children – some for minor offences – some for drink". They were, he once said, "the scum of the earth; it is really wonderful that we should have made them to the fine fellows they are."[5] In Scotland however, a number of men enlisted due to the collapse of the weaving trade and came from skilled artisan or even middle-class households. Most soldiers at the time signed on for life in exchange for a "bounty" of £23 17s 6d, a lot of which was absorbed by the cost of outfitting "necessities",[5] but a system of 'limited service' (seven years for infantry, ten for cavalry and artillery) was introduced in 1806 to attract recruits. Soldiers began, from 1800 onward, to receive a daily Beer money allowance in addition to their regular wages; the practice was started on the orders of the Duke of York.[6] Additionally, corporal punishment was removed for a large number of petty offences (while it was still retained for serious derelictions of duty) and the Shorncliffe System for light infantry was established in 1803, teaching skirmishing, self-reliance and initiative. Unlike other armies of the time, the British did not use conscription to bolster army numbers, with enlistment remaining voluntary.

In periods of long service, battalions generally operated under strength;[5] many discharges and deaths were due to wounds and disease.[5] During the Peninsular Campaign, the army lost almost 25,000 men from wounds and disease while fewer than 9,000 were killed directly in action;[7] however more than 30,000 were wounded in action, and many died in the days or weeks to follow.[8] Seriously under-strength battalions might be dissolved, merged with other remnants into "Provisional battalions" or temporarily drafted into other regiments.[5]

Officers ranged in background also. They were expected to be literate, but otherwise came from varied educational and social backgrounds. Although an officer was supposed also to be a "gentleman", this referred to an officer's character and honourable conduct rather than his social standing. The system of sale of commissions officially governed the selection and promotion of officers, but the system was considerably relaxed during the wars. One in twenty (5%) of the officers from regular battalions had been raised from the ranks, and less than 20% of first commissions were by purchase.[9] The Duke of York oversaw a reform of the sale of commissions, making it necessary for officers to serve two full years before either promotion or purchase to captain and six years before becoming a major,[10] improving the quality of the officers through the gained experience.

Only a small proportion of officers were from the nobility; in 1809, only 140 officers were peers or peers' sons.[9] A large proportion of officers came from the Militia,[9] and a small number had been gentlemen volunteers, who trained and fought as private soldiers but messed with the officers and remained as such until vacancies (without purchase) for commissions became available.[11]

Promotion was mainly by seniority; less than 20% of line promotions were by purchase, although this proportion was higher in the Household Division.[11] Promotion by merit alone occurred, but was less common. By 1814 there were over 10,000 officers in the army.[9]

Civilian support network

Britain mobilized a vast civilian support network to support its 1 million soldiers. Historian Jenny Uglow (2015) explores a multitude of connections between the Army and its support network, as summarized by a review of her book by Christine Haynes:

- a whole host of other civilian, actors, including: army contractors, who provided massive quantities of tents, knapsacks, canteens, uniforms, shoes, muskets, gunpowder, ships, maps, fortifications, meat, and biscuit; bankers and speculators, who funded the supplies as well as subsidies to Britain's allies...revenue agents, who collected the wide variety of taxes imposed to finance the wars; farmers, whose fortunes rose and fell not just with the weather but with the war; elites, who amidst war maintained many of the same old routines and amusements; workers, when the context of war found opportunities for new jobs and higher wages but also grievances that led to strikes and riots; and the poor, who suffered immensely through much of this....[And women who] participated in the war not just as relations of combatants but as sutlers, prostitutes, laundresses, spinners, bandage-makers, and drawing-room news-followers.[12][13]

Infantry

There were three regiments of Foot Guards, each of which had 2 or 3 battalions. In background and natural attributes, many recruits to the Foot Guards differed little from those recruited into other regiments, but they received superior training, were better paid, highly motivated and expected to maintain rigorous discipline.[14]

There were eventually 104 regiments of the line. They were numbered and, from 1781, were given territorial designations, which roughly represented the area from which troops were drawn. This was not entirely rigid, and most regiments had a significant proportion of English, Irish, Scots and Welsh together, except for certain deliberately exclusive regiments.[3] The majority of regiments contained two battalions, while some had only one. One special case, the 60th Foot, ultimately had seven battalions.[3] Battalions were dispersed throughout the army; it was rare for two battalions of any regiment to serve in the same brigade.

A line infantry battalion was commanded by its regimental colonel or a lieutenant colonel, and was composed of ten companies, of which eight were "centre" companies, and two were "flank" companies: one a grenadier and one a specialist light company. Companies were commanded by captains, with lieutenants and ensigns (or subalterns) beneath him.[3] Ideally, a battalion consisted of 1000 men (excluding NCOs, musicians and officers), but active service depleted the numbers. Generally, the 1st (or senior) battalion of a regiment would draw fit recruits from the 2nd battalion to maintain its strength. If also sent on active service, the 2nd battalion would consequently be weaker.[3]

Tactics

In the aftermath of the American War of Independence, during which the British infantry had fought in looser formations than previously, rigid close-order linear formations had been advocated by Major General David Dundas. His 1792 Rules and regulations for the formations, field-exercise, and movements, of His Majesty's forces[15] became the standard drill book for the infantry. As the wars progressed line infantry tactics were developed to allow more flexibility for command and control, placing more reliance upon the officers on the spot for quick reactions.

The line formation was the most favoured, as it offered the maximum firepower, about 1000 to 1500 bullets per minute.[16] Though the manual laid down that lines were to be formed in three ranks, the lines were often formed only two ranks deep, especially in the Peninsula. While the French favoured column formation, the line formation enabled all muskets available to fire at the enemy. In contrast, only the few soldiers in the first rows of the column (about 60) were able to fire.[17] British infantry were far better trained in musketry than most armies on the continent (30 rounds per man in training for example, compared with only 10 in the Austrian Army) and their volleys were notably steady and effective.

The standard weapon of the British infantry was the "India Pattern" version of the Brown Bess musket. This had an effective range of 100 yards, but fire was often reserved until a charging enemy was within 50 yards. Although the French infantry (and, earlier, the Americans) frequently used buck and ball in their muskets, the British infantry used only standard ball ammunition.[18]

Riflemen and light infantry

A number of infantry regiments were newly formed as, or converted into, dedicated regular light infantry regiments. During the early war against the French, the British Army was bolstered by light infantry mercenaries from Germany and the Low Countries, but the British light infantry companies proved inadequate against the experienced and far more numerous French during the Flanders campaign, and in the Netherlands in 1799, and light infantry development became urgent.[19]

The first rifle-armed unit, the 5th Battalion of the 60th Regiment, was formed mainly from German émigrés before 1795. An Experimental Corps of Riflemen, armed with the Baker rifle, was formed in 1800, and was brought into the line as the 95th Regiment of Foot (Rifles) in 1802. Some of the light units of the King's German Legion were also armed with the same weapon. The rifle-armed units saw extensive service, most prominently in the Peninsular War where the mountainous terrain saw them in their element.

In 1803, Sir John Moore converted two regiments (the 43rd Foot and his own regiment, the 52nd Foot), to light infantry at Shorncliffe Camp, the new specialised training camp for light infantry.[20] Five other regiments (the 51st, 68th, 71st, 85th and 90th) were subsequently converted to light infantry. Under Moore, this change of role was accompanied by a change in the methods of training and discipline, encouraging initiative and replacing punishment for minor infractions with a system of rewards for good conduct.

Light infantry and rifle battalions were composed of eight companies. While the rifle-armed units adopted a dark green uniform, the musket-armed light infantry units wore tailless jackets in the traditional red colour.[5] In addition to light infantry duties, they could form up in close order and perform as line infantry if required. They were armed with the "New Light Infantry Land Pattern" of the standard musket, which had a rudimentary backsight to aid individual accuracy, using the bayonet lug as a foresight.

While line regiments fired in volleys, light infantry skirmishers fired at will, taking careful aim at targets.[21]

Uniform

The standard uniform for the majority of regiments throughout the period was the traditional red coat. There was no standardised supply for uniforms, and it was generally left to the regimental colonel to contract for and obtain uniforms for his men, which allowed for some regimental variation.[22] Generally, this was in the form of specific regimental badges, or ornamentation for specialised flank companies, but occasionally major differences existed.[22] Highland regiments generally wore kilts and ostrich feather hats, although six of these regiments exchanged the kilt for regulation trousers or tartan trews in 1809.[5] Officers of Highland regiments wore a crimson silk sash worn from the left shoulder to the right hip. Regimental tartans were worn but they were all derived from the Black Watch tartan. White, yellow or red lines were added to distinguish between regiments. Trousers for the rank and file were generally of white cotton duck canvas for summer use, and grey woolen trousers were issued for winter wear, although considerable variation exists in the color of the woolen trousers. Originally, the white trousers were cut as overalls, designed to be worn to protect the expensive breeches and gaiters worn by the rank and file, although on campaign, they were often worn by themselves; a practice which was later permitted except on parade. Soldiers were also issued with grey greatcoats starting in 1803.[23]

From the last years of the eighteenth century, the bicorne hat was replaced by a cylindrical "stovepipe" shako. In 1812, this was replaced by the false-fronted "Belgic" shako, although light infantry continued to wear the stovepipe version. Grenadiers and Foot Guards continued to be issued bearskins, but these were not worn while on campaign.

It was in 1802, during this period of uniform transition, that enlisted soldier rank insignia were first designated by chevrons. Their introduction allowed the rapid differentiation of sergeants and corporals from private soldiers. Colour sergeant and Lance corporal ranks soon evolved as well.[24]

Officers were responsible for providing (and paying for) their own uniforms. Consequently, variable styles and decorations were present, according to the officer's private means.[22] Officers in the Infantry wore scarlet coattees with long tails fastened with turnbacks. Close-fitting white pantaloons, tucked into tall Hessian or riding boots were worn, often covered with grey wool and leather overalls on campaign, in addition to a dark blue, later grey, double-breasted greatcoat. After 1811, officers were permitted to wear a short tailed coatee, grey pantaloons or trousers and low field boots on campaign. Officers generally wore silver or gold epaulettes (depending on regimental colours), with regimental badge to designate rank. An 1810 order stipulated that subalterns wore one epaulette, on the right shoulder, while captains wore one of a more ornate pattern on the right shoulder. Field officers wore one on each shoulder, badged with a star (for majors), a crown (lieutenant colonels) or star and crown (colonels).[25] Grenadier, fusilier and light infantry officers wore more ornate versions of the shoulder wings their men wore on both shoulders; trimmed with lace, chain or bullion.[26] Generals, from 1812, wore an aiguillette over the right shoulder, and rank was denoted by the spacing of buttons on the coatee: Major generals wore their buttons in pairs, lieutenant generals in threes and full generals wore their buttons singly spaced.

Until the issue of the Belgic shako in 1812, company officers wore bicorne hats; afterwards, they usually wore the same headgear as their men while on campaign, their status as officers denoted with braided cords. Generals, field officers and staff officers generally wore bicorne hats.

Officers were generally armed with the poorly-regarded 1796 Pattern British Infantry Officer's Sword. In light infantry units and the flank companies of line units, they carried the Pattern 1803 sabre instead. In highland regiments, a basket-hilted claymore was generally worn.

Colours

Most British battalions carried flags known as "colours": the First, or "King's Colour", and the Second, or "Regimental Colour". The First had the Union Flag with the Regiment's number in the centre, surrounded by a wreath.[27] The Second was in the colour of the regimental facings with a small Union Flag in the corner and the regimental number in centre.[27] (Units whose facing colours were red or white used a St George's Cross design).[28]

The colours were carried into battle for identification, and as a rallying point, in the care of sergeants or ensigns. Attending the colours in battle was dangerous, since they were a target for enemy artillery and assault. Due to the symbolic significance of the colours, their loss was a grave issue, and extreme measures were often taken to prevent such dishonour occurring.[29] The skirmishing and forward positions maintained by light infantry frequently made the bearing of colours inconvenient. For this reason, the newly raised 95th Rifles received no colours, but the converted line regiments retained their existing colours. Some light infantry regiments opted not to carry them in the Peninsula.[30]

Medals

The widespread use of campaign medals began during the Napoleonic Wars. The Army Gold Medal ("Peninsular Medal"), in round and cross varieties, was issue to battalion commanders and higher ranks for battle service in the Peninsular War. The cross also saw the first use of Medal bars. Following the battle a Waterloo Medal was issued to all soldiers who participated in that engagement. Decades later the Military General Service Medal was awarded to all ranks for service in campaigns during the 1793–1814 period.

Cavalry

At the start of the French Revolutionary Wars, the "heavy" cavalry were equivalent to dragoons or "medium" cavalry in the French and other armies. They consisted of three regiments of Household Cavalry, seven regiments of Dragoon Guards and six regiments of Dragoons. The Dragoon Guards had been regiments of heavy cavalry in the eighteenth century, but had been converted to dragoons to save money. The heavy cavalry wore red uniforms and bicorne hats. From 1796, they were armed with the straight 1796 Heavy Cavalry Sword, a heavy hacking sword which was reckoned to be useless for thrusting, and also carried a long carbine. (The Scots Greys wore a bearskin headdress and had a more curved sword.)

The light cavalry units consisted of fourteen regiments of Light Dragoons, which had been formed during the eighteenth century to carry out the roles of scouting and patrolling. In many cases, the regiments were originally troops attached to heavy regiments, before being separated from them and expanded. Some regiments were raised specifically to serve overseas; the 19th and 25th (later the 22nd) Light Dragoons to serve in India, and the 20th to serve in Jamaica. The light dragoons wore short blue braided jackets and the leather Tarleton helmet which had a thick woollen comb. They were armed with the Pattern 1796 light cavalry sabre, which was very sharply curved and generally used for cutting only.[31] Later in the period, light cavalry carried the short "Paget" carbine, which had a ramrod attached by a swivel for convenient use.

In 1806, four light dragoon regiments (the 7th, 10th, 15th and 18th) were converted into regiments of Hussars, with no change in their role, but a great increase in the expense of their uniforms. From 1812, the uniforms of most of the remaining British cavalry changed, following French styles. The heavy cavalry (excepting the Household Cavalry who adopted a helmet with a prominent woolen comb and the Scots Greys, who retained their bearskins) adopted a helmet with a horsetail crest like those of French dragoons or cuirassiers, while the light dragoons adopted a jacket and shako similar to those of French chasseurs a cheval. The Duke of Wellington objected to these changes, as it became difficult to distinguish French and British cavalry at night or at a distance, but without success.

For most of the wars, British cavalry formed a lower proportion of armies in the field than most other European armies, mainly because it was more difficult to transport horses by ship than foot soldiers, and the horses usually required several weeks to recuperate on landing. British cavalry were also more useful within Britain and Ireland for patrolling the country as a deterrent to unrest. Some exceptions were Wellington's Vitoria campaign in 1813, when he required large numbers of cavalry to ensure a decisive result to the campaign, and the Waterloo campaign, where the cavalry needed to be transported only across the English Channel.

The British cavalry was usually organised into brigades, but no higher formations. (The cavalry division referred to all cavalry units of an army.) Brigades were attached to infantry divisions or columns, or sometimes acted directly under the command of the cavalry commander of an army.

British cavalry were excellently mounted and were reckoned superior to French cavalry if squadrons clashed, but because brigades and even regiments were rarely exercised in battlefield manoeuvres and tactics, they were inferior in larger numbers.[32] Wellington in particular was highly unimpressed by the quality and intelligence of many of his cavalry officers. He said:

I considered our (British) cavalry so inferior to the French from the want of order, that although I considered one squadron a match for two French, I didn't like to see four British opposed to four French: and as the numbers increased and order, of course, became more necessary I was the more unwilling to risk our men without having a superiority in numbers.[33]

Foreign units in British service

During the wars, many émigré units were formed from refugees from countries occupied by France, and from among deserters and prisoners of war from the French armies.

The oldest of these was the 60th Regiment, which had originally been raised in 1756 for service in America, and which had long been composed primarily of Germans. During the Napoleonic Wars, most of the seven battalions of this regiment served as garrison troops in territories such as the West Indies, but the 5th battalion was raised in 1797 from two other emigre units (Hompesch's Mounted Riflemen and Lowenstein's Chasseurs) as a specialised corps of skirmishers armed with the Baker Rifle, and the 7th battalion was specifically formed to serve in North America during the War of 1812.

The largest émigré corps was the King's German Legion, which was formed in 1803 and was composed mainly of German exiles from Hanover and other north German states. In total, it formed two dragoon regiments (which later became light dragoons), three hussar regiments, eight line and two light infantry battalions, and five artillery batteries. Although it never fought as an independent force, its units were often brigaded together. The units of the Legion were regarded as the equal of the best regular British units.

The Royal Corsican Rangers were formed in 1798 from among Corsican exiles on Menorca. After being disbanded during the Peace of Amiens, the regiment was reformed in 1803 from Corsicans and Italians (Italian was the main language spoken among Corsicans). It served in the Mediterranean, and was not disbanded until 1817.

The King's Dutch Brigade was formed from former personnel of the Dutch States Army (defunct since 1795), who had emigrated to Germany and Britain after the Dutch Republic was overthrown by the Batavian Republic; from deserters from the Batavian army; and mutineers of the Batavian naval squadron that had surrendered to the Royal Navy in the Vlieter Incident, all during the Anglo-Russian invasion of Holland in 1799. The brigade was commissioned on 21 October 1799 on the Isle of Wight, after it had been organised by the Hereditary Prince of Orange who had been an allied commander during the Flanders Campaign of 1793–95. The troops swore allegiance, both to the British Crown, and to the defunct States-General of the Netherlands, the former sovereign power in the Dutch Republic. The troops received both the King's Colours and regimental colours after Dutch model. The brigade counted four regiments of infantry of 18 companies each, 1 regiment of Chasseurs (also of 18 companies), 1 battalion of artillery of 6 companies, and a corps of engineers (96 companies total). The brigade was used in Ireland in 1801, and later on the Channel islands. It was decommissioned on 12 July 1802, after the Peace of Amiens, after which most personnel (but not all) returned to the Batavian Republic, under an amnesty in connection with that treaty.[34]

The Dutch Emigrant Artillery was formed in Hanover in 1795 from remnants of Franco-Dutch units. It consisted of three companies and between 1796 and 1803 served in the West Indies to man guns in forts there. In 1803 it was amalgamated into the Royal Foreign Artillery.

The Chasseurs Britanniques were originally formed from French Royalist emigres in 1801, and served throughout the wars.[35] The unit served chiefly in the Mediterranean until 1811, when it participated in the later stages of the Peninsular War. It had a good record in battle but later became notorious for desertion, and was not even allowed to perform outpost duty, for fears that the pickets would abscond.

In 1812, the Independent Companies of Foreigners were formed from among French prisoners of war for service in North America. The companies became notorious for lack of discipline and atrocities in Chesapeake Bay, and were disbanded.

The nominally Swiss Regiment de Meuron was transferred from the Dutch East India Company in Ceylon in 1798. It consisted even when first transferred of soldiers of mixed nationalities, and later recruited from among prisoners of war and deserters from all over Europe. It later served in North America. Two Swiss units in French service were also taken into British service about the same time. The Regiment de Roll was originally created from the disbanded Swiss Guards in the pay of France. Dillon's regiment was also formed from Swiss émigrés from French service. These two regiments were merged into a single provisional battalion, termed the Roll-Dillon battalion, at some stage in the Peninsular War. The Regiment de Watteville was another nominally Swiss unit, which actually consisted of many nationalities. It was formed in 1801 from the debris of four Swiss regiments formed by the British for Austrian service, and served at the Siege of Cadiz and in Canada in 1814.

The British Army also raised units in territories that were allied to Britain or that British troops occupied. These included the Royal Sicilian Volunteers and two battalions of Greek Light Infantry. Initially the 1st Greek Light Infantry was formed,[36] then by 1812 The Duke of York's Greek Light Infantry Regiment[37][38] and in 1813 a second regiment composed of 454 Greeks 2nd Regiment Greek Light Infantry) which occupied Paxoi islands.[39] These regiments included many of the men who were afterwards among the leaders of the Greeks in the War of Independence, such as Theodoros Kolokotronis.

During early part of the Peninsular War, some Portuguese soldiers were organised into a Corps known as the Loyal Lusitanian Legion, which eventually was absorbed by the Portuguese Army.

Canadian units

Four regiments of Fencibles were raised before 1803 in Canada or the Maritime provinces (Newfoundland, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick) as regulars for service in North America. (The New Brunswick Fencibles volunteered for general service and became the 104th Regiment of Foot, but did not serve outside the continent.) A fifth fencible regiment (the Glengarry Light Infantry) was raised as war with the United States of America appeared inevitable. There were also ad-hoc units, such as the Michigan Fencibles and the Mississippi Volunteer Artillery which served in a specific theatre, such as the west around Prairie du Chien and Credit Island.

When the War of 1812 broke out, six (later eight) battalions of Select Embodied Militia were formed for full-time service from among the militia or from volunteers. One of these units, the Canadian Voltigeurs, was treated as a regular unit for most purposes. There were also several volunteer company-sized units of dragoons or rangers, and detachments of artillery. A militia company composed entirely of Negroes later became a full-time pioneer unit.

After the end of the War in 1815, almost all the fencible and volunteer units were disbanded. Many of the troops and British soldiers discharged in Canada received land grants and became settlers.

Daily life

While on campaign, it was customary for men to sleep in the open, using their blankets or greatcoats for warmth.[40] Simple blanket tents could be made from two blankets, supported by firelocks, a ramrod, and fixed to the ground with bayonets.[40] At other times, huts could be made using branches covered with ferns, straw or blankets.[41] While tents were frequently used by officers, they were not issued to the men until 1813.[42]

Soldiers were allowed to marry, but wives were expected to submit to army rules and discipline, as well contribute to regimental affairs by performing washing, cooking and other duties. Six women per company were officially "on the strength" and could accompany their husbands on active service, receiving rations and places on troop transports. If there was competition for these places, selections would be made by ballot.[43] Many soldiers also found wives or companions from amongst the local populations, whose presence in the army train was generally tolerated, despite being beyond the quota.[44] However, at the conclusion of the Peninsular War only those wives officially on the strength were allowed to return to Britain with their husbands, resulting in a large number of women and children abandoned in France, with no provisions or means of returning to their homes.

Officers also needed permission from their commanding officers to marry, and for their wives to accompany them, but they were not subject to quota, although restrictions might be made due to the officer's age or seniority.[45]

Campaigns

The British Army fought on a number of fronts during the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic wars, with a brief pause from 1802 to 1803 (and from 1814 to 1815, after Bonaparte abdicated for the first time).

French Revolutionary Wars

Mysore, 1789–1792

The first major engagement involving the British army during the Revolutionary period was the Third Anglo-Mysore War, between Kingdom of Mysore supported by France and led by Tipu Sultan, and the British East India Company supported by its local allies. British regular infantry and artillery regiments formed the core of the East India Company army serving under the command of British general Lord Cornwallis. After some initial setbacks, Cornwallis was ultimately victorious capturing the Mysorean capital city of Seringapatam and compelling Mysore to make peace on terms favourable to Britain.

Toulon

In 1793, French Royalists in Toulon surrendered their port and city to a British fleet under Vice Admiral Samuel Hood. A land force of 18,000 of mixed nationalities, including 2,000 British (mainly Royal Marines), gathered to protect Toulon against a French Republican counter-attack. The commander of the British contingent, Lieutenant General Charles O'Hara, was captured in a minor skirmish, by Captain Napoleon Bonaparte who inspired the besiegers of the port. After the French captured vital forts which commanded the town and harbour, the British and their allies evacuated the port.

British troops and ships seized the island of Corsica, turning it temporarily into the Anglo-Corsican Kingdom. Relations between the British and Corsicans soured, and the island was evacuated after Spain declared war on Britain, making it impossible for the Royal Navy to maintain communications with the island.

Flanders, 1793–1796

In this theatre a British army under the command of the Duke of York formed part of an Allied army with Hanoverian, Dutch, Hessian, Austrian and Prussian contingents, which faced the French Republican Armée du Nord, the Armée des Ardennes and the Armée de la Moselle. The Allies enjoyed several early victories, (including a largely British-fought battle at Lincelles[46]), but were unable to advance beyond the French border fortresses and were eventually forced to withdraw by a series of victorious French counter-offensives.

The Allies then established a new front in southern Holland and Germany, but with poor co-ordination and failing supplies were forced to continue their retreat through the arduous winter of 1794/5. By spring 1795 the British force had left Dutch territory entirely, and reached the port of Bremen where they were evacuated. The campaign exposed many shortcomings in the British army, especially in discipline and logistics, which had developed in the ten years of peacetime neglect since the American Revolution.

West Indies, 1793–1798

The other major British effort in the early French Revolutionary Wars was mounted against the French possessions in the West Indies. This was mainly for trade considerations; not only were the French islands valuable for their plantations, but they were also used by French privateers preying on British merchant ships.

The resulting five-year campaign crippled the whole British Army through disease, especially yellow fever. Out of 89,000 soldiers and NCOs who served in the West Indies, 43,747 died of yellow fever or other tropical diseases. Another 15,503 were discharged, no longer fit for service, or deserted.[47] The islands of Martinique, Guadeloupe and ports in Haiti were captured in 1794 and 1795 by expeditionary forces under General Charles Grey, but the British units were almost exterminated by disease. Negro and mulatto insurgent armies in Haiti which had first welcomed the British as allies turned against them. Guadeloupe was recaptured in 1796 by Victor Hugues, who subsequently executed 865 French Royalists and other prisoners.[48]

Eight thousand reinforcements under Lieutenant General Sir Ralph Abercromby arrived in 1796, and secured many French territories, and those of Spain and the Netherlands (which was now titled the Batavian Republic and allied to France). However, the decimated British troops evacuated Haiti, and Guadeloupe was never recaptured, becoming a major privateering base and black market emporium.

Muizenberg and Ceylon 1795

In 1795 a combined British army and Royal Navy force under the command of Major-General James Craig and Admiral Elphinstone captured the Dutch Cape Colony. It remained in British possession for seven years until the Peace of Amiens. At the same time another British force captured the Dutch colony of Trincomalee, Ceylon, which remained in British possession until 1948.

Ireland 1798

A rebellion inspired by a secret society, the Society of United Irishmen, broke out in Ireland. The British Army in Ireland consisted partly of regular troops but mostly of Protestant militia and Irish Yeomanry units. The rebellion was marked by atrocities on both sides.

After the rebellion had already failed, a French expedition under General Humbert landed in the west of Ireland. After inflicting an embarrassing defeat on a British militia force at the Battle of Castlebar, Humbert's outnumbered army was surrounded and forced to surrender.

Mysore, 1798–1799

This was the last war fought between the East India Company and the Kingdom of Mysore. British regular regiments again formed part of the East India Company army, this time under the command of British general George Harris. The British forces defeated Mysore for the final time, capturing Seringapatam and killing Tipu Sultan.

Holland 1799

As part of the War of the Second Coalition, a joint Anglo-Russian force invaded the Netherlands. Although the British troops captured the Dutch fleet, but after the defeat at Castricum, the expedition was a failure and the British commander in chief, the Duke of York negotiated a capitulation which allowed the British to sail away unmolested.

Egypt

In 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte had invaded Egypt, as a stepping stone to India, which was the source of much of Britain's trade and wealth. He was stranded there when Vice Admiral Nelson destroyed the French fleet at the Battle of the Nile.

In alliance with the Ottoman Empire, Britain mounted an expedition to expel the French from Egypt. After careful preparations and rehearsals in Turkish anchorages, a British force under Sir Ralph Abercromby made a successful opposed landing at the Battle of Abukir (1801). Abercromby was mortally wounded at the Battle of Alexandria, where the British troops demonstrated the effectiveness of their musketry, improved discipline and growing experience. The French capitulated and were evacuated from Egypt in British ships.

Peace of Amiens

After Britain's allies all signed treaties with France, Britain also signed the Treaty of Amiens, under which Britain restored many captured territories to France and its allies. The "peace" proved merely to be an interlude, with plotting and preparations for a renewal of war continuing on both sides.

Napoleonic Wars

Maratha, 1803–1805

Shortly after the resumption of war on the continent, the East India Company once again became involved in war with an Indian power, this time with the Maratha Empire, supported by France. British regiments of infantry, artillery and cavalry once again formed the core of the Company army, this time under the command of British generals Gerrard Lake and Arthur Wellesley. Maratha forces were defeated decisively at Assaye and Delhi and further losses eventually compelled them to make peace.

West Indies, 1804–1810

When war resumed, Britain once again attacked the French possessions in the West Indies. The French armies which had been sent to recover Haiti in 1803 had, like the British armies earlier, been ravaged by disease, so only isolated garrisons opposed the British forces. In 1805, as part of the manoeuvres which ultimately led to the Battle of Trafalgar, a French fleet carrying 6,500 troops briefly captured Dominica and other islands but subsequently withdrew.

In 1808, once the British were allied to Portugal and Spain, they were able to concentrate their forces and capture the French possessions one by one; Cayenne and Martinique in 1809, and Guadeloupe in 1810. Haiti was left to the insurgent armies.

Hanover 1805

In 1805 news arrived in London that Napoleon had broken up his invasion camp at Boulogne, and was marching across Germany. The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom William Pitt immediately equipped an army of 15,000 men, and deployed it to Hanover under the command of General William Cathcart, with the intention of linking up with another allied Russian army and creating a diversion in favour of Austria, but Cathcart made no attempt to attack the flank of the far larger French army. Cathcart established his headquarters at Bremen, seized Hanover, fought a small battle at Munkaiser, and then peacefully waited for news. After the death of Pitt and news of the Franco-Prussian agreement handing control of Hanover to Prussia, the ministry recalled Cathcart's army from Germany.[49]

Naples 1805

One of Britain's allies was Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies, whose kingdom was important to British interests in the Mediterranean. In 1805 British forces under the command of General James Craig were part of an Anglo-Russian force intended to secure the Kingdom of Naples. However, after a brief occupation the allied position became untenable with the news of the disastrous Austrian defeat at the Battle of Ulm.

Sicily and the Mediterranean

In 1806, French troops invaded southern Italy, and British troops again went to aid the defenders. A British army under the command of General John Stuart won a lopsided victory at the Battle of Maida. For the rest of the war, British troops defended Sicily, forcing Ferdinand to make liberal reforms. An allied force consisting mainly of Corsicans, Maltese and Sicilians was driven from Capri in 1808. The next year, British troops occupied several Greek and Dalmatian islands, although the French garrison on Corfu was too strong to be attacked. The British retained their Greek islands until the end of the wars.

South Africa and the Plate

The Dutch colony at the Cape of Good Hope was a vital port of call on the long sea voyage to India. An expedition was sent to capture it in 1805. (It had first been captured in 1796, but was returned under the Treaty of Amiens.) British troops under Lieutenant General Sir David Baird won the Battle of Blaauwberg in January 1806, forcing the surrender of the colony.

The naval commander of the expedition, Admiral Home Riggs Popham then conceived the idea of occupying the Spanish Plate River colonies. A detachment under Major General William Carr Beresford occupied Buenos Aires for six weeks, but was expelled by Spanish troops and local militias.

General Auchmuty mounted a second invasion of the region in 1807, capturing Montevideo. Lieutenant General Sir John Whitelocke was sent from Britain to take command in the region, arriving at the same time as Major General Robert Craufurd, whose destination had been changed several times by the government, and whose troops had been aboard ship for several months.[50]

Whitelock launched a bungled attack on Buenos Aires on 5 July 1807, in which the British troops suffered heavy casualties and were trapped in the city. Finally he capitulated, and the troops returned ignominiously to Britain. Whitelock was court-martialled and cashiered.

Denmark

In August 1807, an expedition was mounted to Copenhagen, to seize the Danish fleet to prevent it falling into French hands. The expedition was led by General Lord Cathcart. A British land force under the command of Arthur Wellesley routed a Danish militia force. After the city was bombarded for several days, the Danes surrendered their fleet.

Alexandria

In 1807 an army and navy expedition under the command of General Alexander Mackenzie Fraser was dispatched with the objective of capturing the Egyptian city of Alexandria to secure a base of operations to disrupt the Ottoman Empire. The people of Alexandria, being disaffected towards Muhammad Ali of Egypt, opened the gates of the city to the British forces, allowing for one of the easiest conquests of a city by the British forces during the Napoleonic Wars. However, due to lack of supplies, and inconclusive operations against the Egyptian forces, the Expedition was forced to re-embark and leave Alexandria.

Walcheren

In 1809, Austria declared war on France. To provide a diversion, a British force consisting mainly of the troops recently evacuated from Corunna was dispatched to capture the Dutch ports of Flushing and Antwerp. There were numerous delays, and the Austrians had already surrendered when the army sailed. The island of Walcheren, where they landed, was pestilential and disease-ridden (mainly with malaria or "ague"). Although Flushing was captured, more than one third of the soldiers died or were incapacitated before the army was withdrawn.

Indian Ocean and East Indies

To clear nests of French privateers and raiders, the Army captured the French dependencies in the Indian Ocean in the Mauritius campaign of 1809–1811. With substantial contingents from the East India Company, British troops also captured the Dutch colonies in the Far East in 1810 with the successful Invasion of the Spice Islands and 1811, with the fall of Java.

Peninsular War

Sir William Napier on the Peninsular War.[51]

In 1808, after Bonaparte overthrew the monarchs of Spain and Portugal, an expedition under Sir Arthur Wellesley which was originally intended to attack the Spanish possessions in Central America was diverted to Portugal. Wellesley won the Battle of Vimeiro while reinforcements landed at nearby Maceira Bay.[52] Wellesley was superseded in turn by two superiors, Sir Harry Burrard and Sir Hew Dalrymple, who delayed further attacks. Instead, they signed the Convention of Sintra, by which the French evacuated Portugal (with all their loot) in British ships. Although this secured the British hold on Lisbon, it resulted in the three generals' recall to England, and command of the British troops devolved on Sir John Moore.[53]

In October, Moore led the army into Spain, reaching as far as Salamanca. In December, they were reinforced by 10,000 troops from England under Sir David Baird.[53] Moore's army now totalled 36,000, but his advance was cut short by the news that Napoleon had defeated the Spanish and captured Madrid, and was approaching with an army of 200,000. Moore retreated to Corunna over mountain roads and through bitter winter weather.[53] French cavalry pursued the British Army the length of the journey, and a Reserve Division was set to provide rearguard protection for the British troops, which were engaged in much fighting.[53] About 4,000 troops separated from the main force and marched to Vigo.[54] The French caught up with the main army at Corunna, and in the ensuing Battle of Corunna in January 1809, Moore was killed; the remnant of the army was evacuated to England.[53]

In 1809, Wellesley returned to Portugal with fresh forces, and defeated the French at the Second Battle of Porto, driving them from the country. He again advanced into Spain and fought the Battle of Talavera and the Battle of the Côa. He and the Spanish commanders were unable to cooperate, and he retreated into Portugal, where he constructed the defensive Lines of Torres Vedras which protected Lisbon, while he reorganised his Anglo-Portuguese Army into divisions, most of which had two British brigades and one Portuguese brigade.

The next year, when a large French army under Marshal André Masséna invaded Portugal, Wellesley fought a delaying action at the Battle of Bussaco, before withdrawing behind the impregnable Lines, leaving Massena's army to starve in front of them. After Massena withdrew, there was fighting for most of 1811 on the frontiers of Portugal, as Wellesley attempted to recover vital fortified towns. A British and Spanish force under Beresford fought the very bloody Battle of Albuera, while Wellesley himself won the Battle of Sabugal in April, and the Battle of Fuentes de Onoro in May.

In January 1812, Wellesley captured Ciudad Rodrigo after a surprise move. On 6 April, he then stormed Badajoz, another strong fortress, which the British had failed to carry on an earlier occasion. There was heavy fighting with very high casualties and Wellesley ordered a withdrawal, but a diversionary attack had gained a foothold by escalade and the main attack through the breaches was renewed. The fortress was taken, at great cost (over 5000 British casualties), and for three days the army sacked and pillaged the town in undisciplined revenge.[55]

Soon after the assault on Badajoz, Wellesley (now raised to the peerage as Marquess Wellington) marched into northern Spain. For a month the British and French armies marched and counter-marched against each other around Salamanca. On 22 July, Wellington took advantage of a momentary French dispersion and gained a complete victory at the Battle of Salamanca.[55] After occupying Madrid, Wellington unsuccessfully besieged Burgos. In October, the army retreated to Portugal. This "Winter Retreat" bore similarities to the earlier retreat to Corunna, as it suffered from poor supplies, bitter weather and rearguard action.[56]

In spring 1813, Wellington resumed the offensive, leaving Portugal and marching northwards through Spain, dropping the lines of communication to Lisbon and establishing new ones to the Spanish ports on the Bay of Biscay. At the Battle of Vitoria the French armies were routed,[57] disgorging an enormous quantity of loot, which caused the British troops to abandon the pursuit and break ranks to plunder. Wellington's troops subsequently defeated French attempts to relieve their remaining fortresses in Spain. During the autumn and winter, they forced the French defensive lines in the Pyrenees and crossed into France, winning the Battle of Nivelle, the Battle of Nive and the Battle of Orthez in February 1814.[57] In France, the discipline of Wellington's British and Portuguese troops was far superior to that of the Spanish, and even that of the French, thanks to plentiful supplies delivered by sea.

On 31 March 1814, allied armies entered Paris, and Napoleon abdicated on 6 April.[58] The news was slow to reach Wellington, who fought the indecisive Battle of Toulouse on 10 April.[59]

Once peace agreements had finally been settled, the army left the Peninsula. The infantry marched to Bordeaux for transportation to their new postings (several to North America). Many Spanish wives and girlfriends were left behind, to general distress. The cavalry rode through France to Boulogne and Calais.[60]

Holland 1814

In 1814, the British government had sent a small force to Holland under Sir Thomas Graham to capture the fortress of Bergen op Zoom. The attack, on 8 March 1814, failed and the British were repelled, with heavy losses.[61]

War in North America

Although the United States of America was not allied to France, war broke out between America and Britain ostensibly over issues of trade embargoes and impressment of American sailors into the Royal Navy, both of which were directly or indirectly linked to the Napoleonic wars (the latter of which was not even brought up during the Treaty of Ghent). For the first two years of the war, a small number of British regular units formed the hard core around which the Canadian militia rallied. Multiple US invasions north of the border were repulsed; such an example can be seen at the Battle of Crysler's Farm in which battalions of 89th and 49th Regiments attacked and routed a significantly larger American force making its way toward Montreal.

In 1814, larger numbers of British regulars became available after the abdication of Napoleon. However, long and inadequate supply lines constrained the British war effort. In Chesapeake Bay, a British force captured and burned Washington, but was repulsed at Baltimore. Neither side could strike a decisive blow which would compel the other to cede favourable terms, and the Treaty of Ghent was signed. Before news of it could reach the armies on the other side of the Atlantic, a British force under Wellington's brother-in-law Sir Edward Pakenham was defeated foolhardily attacking heavily fortified positions at the Battle of New Orleans.

Waterloo Campaign 1815

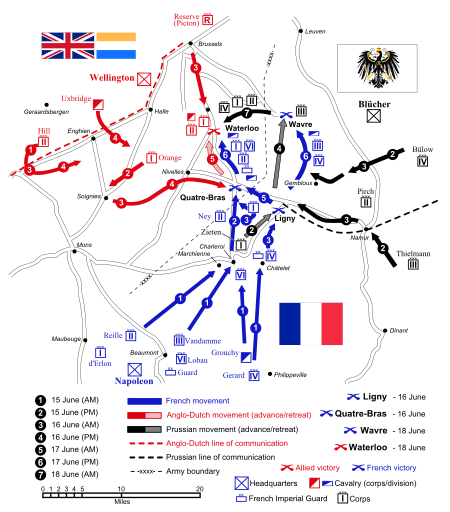

It appeared that war was finally over, and arrangements for the peace were discussed at the Congress of Vienna. But on 26 February 1815, Napoleon escaped from Elba and returned to France, where he raised an army. By 20 March he had reached Paris.[62] The Allies assembled another army and planned for a summer offensive.[63]

Basing themselves in Belgium, the Allies formed two armies, with the Duke of Wellington commanding the Anglo-Allies, and Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher commanding the Prussians. Napoleon marched swiftly through France to meet them, and split his army to launch a two-pronged attack. On 16 June 1815, Napoleon himself led men against Blücher at Ligny, while Marshall Ney commanded an attack against Wellington's forward army at the Battle of Quatre Bras. Wellington successfully held Quatre Bras, but the Prussians were not so successful at Ligny, and were forced to retreat to Wavre. Hearing of Blücher's defeat on the morning of 17 June, Wellington ordered his army to withdraw on a parallel course to his ally; the British and Belgians took position near the Belgian village of Waterloo.

On the morning of 18 June, one of the greatest ever feats of British arms began: The Battle of Waterloo. The British, Dutch, Belgian, Nassau and German troops were posted on higher ground south of Waterloo. There had been heavy rain overnight and Napoleon chose not to attack until almost midday. The delay meant that the Prussians had a chance to march towards the battle, but in the meantime, Wellington had to hold on. The French started their attack with an artillery bombardment. The first French attacks were then directed against the Chateau of Hougemont down from the main ridge. Here British and Nassau troops stubbornly defended the Hougomont buildings all day; the action eventually engaging a whole French Corps which failed to capture the Chateau. At half past one, the Anglo-Allied Army was assaulted by d'Erlon's infantry attack on the British left wing but the French were forced back with heavy losses. Later in the afternoon, British troops were amazed to see waves of cavalrymen heading towards them. The British troops, as per standard drill, formed infantry squares (hollow box-formations four ranks deep) after which the French cavalry was driven off. The British position was critical after the fall of La Haye Sainte, but fortunately, the Prussians started entering the battlefield. As the Prussian advance guard began to arrive from the east, Napoleon sent French units to stabilise his right wing. At around seven o'clock, Napoleon ordered his Old and Middle Guard to make a final desperate assault on the by now fragile Allied line. The attack was repulsed. At that point Wellington stood up and waved his hat in the air to signal a general advance. His army rushed forward from the lines in a full assault on the retreating French. Napoleon lost the battle.

Later history

Following the conclusion of the wars, the army was reduced. At this time, infantry regiments existed up to 104th Foot, but between 1817 and 1819, the regiments numbered 95th Foot up were disbanded,[64] and by 1821 the army numbered only 101,000 combatants, 30% of which were stationed in the colonies, especially India.[65] Over the following decades, various regiments were added, removed or reformed to respond to military or colonial needs,[64] but it never grew particularly large again until the First World War, and the Empire became more reliant on local forces to maintain defence and order.[65]

See also

- Army of Spain (Peninsular War)

- British Volunteer Corps

- Chronology of events of the Peninsular War

- Coalition forces of the Napoleonic Wars

- Fencibles

- Grande Armée

- History of the British Army

- Militia (Great Britain)

- Militia (United Kingdom)

- National Army Museum

- Napoleonic Wars casualties

- The United Kingdom in the Napoleonic Wars

- Timeline of the British Army

- Types of military forces in the Napoleonic Wars

Notes

- Chappell 2004, p. 8.

- Chandler & Beckett 2003, p. 132.

- Haythornthwaite 1987, p. 6.

- McGuigan 2003.

- Haythornthwaite 1987, p. 7.

- Haythornthwaite 1995, pp. 30–31.

- Glover 1974, p. 37.

- Dumas & Vedel-Petersen 1923, pp. 36–37.

- Haythornthwaite 1987, p. 8.

- Holmes 2002, p. 158.

- Haythornthwaite 1987, p. 9.

- Christine Haynes, Review, ‘’Journal of military history April 2016 80#2 p 544

- Jenny Uglow, In These Times: Living in Britain Through Napoleon's Wars, 1793–1815 (2015)

- Fletcher & Younghusband 1994, p. 13.

- Online version of Rules and regulations for the formations, field-exercise, and movements, of His Majesty's forces at the Internet Archive

- Haythornthwaite 1996, p. 26.

- Haythornthwaite 1996, p. 5.

- Chappell 2004, p. 14.

- Chappell 2004, pp. 9–10.

- Chappell 2004, p. 11.

- Chappell 2004, pp. 14–15.

- Haythornthwaite 1987, p. 14.

- Haythornthwaite 1987, p. 24.

- Ranks

- Haythornthwaite 1987, p. 37.

- Fletcher, Younghusband 1994, p. 27.

- Sumner & Hook 2001, p. 3.

- Yaworsky 2013.

- Sumner & Hook 2001, pp. 20–1.

- Sumner & Hook 2001, pp. 22–23.

- Read 2001.

- Napoleonistyka 2013.

- Oman & Hall 1902, p. 119.

- Ringoir 2006, p. .

- Chartrand 2000, p. .

- "Greek Light Infantry". The National Archives. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- "1st (The Duke of York's) Greek Light Infantry Regiment (1811–1816)". The National Archives. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- Steve Brown. "Heroes and Villains: Death and Desertion in the British Army 1811 to 1813". Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- René Chartrand, Patrice Courcelle (2000). Émigré & Foreign Troops in British Service (2) 1803–15. Osprey Publishing. p. 20. Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- Bluth 2001, p. 62.

- Bluth 2001, p. 63.

- Bluth 2001, p. 65.

- Venning 2005, p. 31.

- Venning 2005, p. 15.

- Venning 2005, p. 14.

- quoted, Phipps 1926, I, p. 215.

- Knight 2014, p. 76.

- Fregosi 1989, p. 96.

- Stephens 1887, pp. 288–289.

- Fregosi 1989, p. 279.

- Napier 1952, p. 549.

- Chappell 2004, p. 17.

- Chappell 2004, p. 18.

- Glover 1974, p. 82.

- Chappell 2004, p. 24.

- Chappell 2004, p. 33.

- Chappell 2004, p. 34.

- Glover 1974, p. 326.

- Glover 1974, p. 329.

- Bryant 1950, p. 98.

- Bryant 1950, p. 86.

- Nofi 1998, pp. 19, 28.

- Nofi 1998, p. 31.

- Haythornthwaite 1995, p. 19.

- Haythornthwaite 1995, p. 18.

References

- Bluth, BJ (2001), Marching with Sharpe, UK: HarperCollins, ISBN 0-00-414537-2

- Bryant, Arthur (1950), The Age of Elegance: 1812–1822, London: Collins,

- Chandler, David; Beckett, Ian; (2003) The Oxford History of the British Army, UK: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-280311-5

- Chappell, Mike; (2004) Wellington's Peninsula Regiments (2): The Light Infantry, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-84176-403-5

- Chartrand, René (2000), Émigré and Foreign Troops in British Service (2), Osprey, ISBN 978-1-85532-859-4

- Dumas, Samuel; Vedel-Petersen, K.O. (1923), Losses of Life Caused by War, pp. 36–37

- Fletcher, Ian; Younghusband, William; (1994) Wellington's Foot Guards, UK: Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-85532-392-3

- Fregosi, Paul (1989), Dreams of Empire: Napoleon and the first World War, 1792–1815, Hutchinson, ISBN 0-09-173926-8

- Glover, Michael; (1974) The Peninsular War 1807–1814: A Concise Military History, UK: David & Charles, ISBN 0-7153-6387-5

- Haythornthwaite, Philip J. (1987), British Infantry of the Napoleonic Wars, London: Arms and Armour Press, ISBN 0-85368-890-7

- Haythornthwaite, Philip J. (1995), The Colonial Wars Sourcebook, London: Arms and Armour Press, ISBN 1-85409-196-4

- Haythornthwaite, Philip J. (1996), Weapons & Equipment of the Napoleonic Wars Arms and Armour ISBN 1-85409-495-5

- Holmes, R. (2002), Redcoat: The British Soldier in the Age of Horse and Musket, p. 158

- Knight, Roger (2014), Britain against Napoleon: The Organization of Victory 1793 – 1815, Penguin, p. 76, ISBN 978-0-141-03894-0

- McGuigan, Ron (May 2003), The British Army: 1 February 1793, The Napoleon Series, retrieved 24 November 2014

- Napier, Sir William (1952), English Battles and Sieges in the Peninsula, London: Chapman & Hall, online

- British Cavalry of the Napoleonic Wars, Napoleonistyka, 31 July 2013, retrieved 24 November 2014

- Nofi, Albert A. (1998), The Waterloo Campaign: June 1815, USA: Da Capo Press, ISBN 0-938289-98-5

- Oman, Charles; Hall, John A. (1902), A History of the Peninsular War, Clarendon Press, p. 119

- Phipps, Ramsey Weston (1926), The Armies of the First French Republic and the Rise of the Marshals of Napoleon I, London: Oxford University Press

- Read, Martin (July 2001), The 1796 Pattern Light Cavalry sabre, The Napoleon Series, retrieved 24 November 2014

- Ringoir, H. (8 May 2006), Het ontstaan van de Hollandse Brigade in Engelse Dienst 1799–1802 (PDF) (in Dutch), retrieved 6 April 2013

- Sumner, Ian; Hook, Richard (2001), British Colours and Standards 1747–1881 (2): Infantry, UK: Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-84176-201-6

- Venning, Annabel (2005), Following the Drum: The Lives of Army Wives and Daughters Past and Present, London: Headline Publishing, ISBN 0-7553-1258-9

- Yaworsky, Jim (25 September 2013), The 41st Regiment and the War of 1812, Warof1812.ca, a subsidiary of The Discriminating General, retrieved 24 November 2014

Attribution

External links

- Redcoat: Officer fatality lists

- London Gazette archives – army and battle dispatches; officer appointments, promotions and casualties