Hunin

Hunin (Arabic: هونين) was a Palestinian Arab village in the Galilee Panhandle part of Mandatory Palestine close to the Lebanese border. It was the second largest village in the district of Safed, but was depopulated in 1948.[6]

Hunin هونين | |

|---|---|

Village | |

| Etymology: from personal name,[1] | |

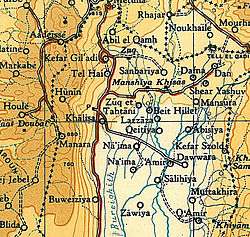

.jpg) .jpg) .jpg) .jpg) A series of historical maps of the area around Hunin (click the buttons) | |

Hunin Location within Mandatory Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 33°13′8″N 35°32′43″E | |

| Palestine grid | 201/291 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Safad |

| Date of depopulation | 3 May 1948 and September 1948[2] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 14,224 dunams (14.224 km2 or 5.492 sq mi) |

| Population (1945) | |

| • Total | 1,620[3][4] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Fear of being caught up in the fighting |

| Secondary cause | Expulsion by Yishuv forces |

| Current Localities | Misgav Am[5] Margaliot[5] |

History

The site has sporadic habitation dating from Iron Age 1 (1200-1000BCE) and continuous habitation from circa 550 to 350 BCE until circa 550 CE, then sporadic habitation again until the 1800s.[7]

Crusader period

The castle named Chastel Neuf or Castellum Novum in Frankish chronicles, Qal'at Hunin in Arabic, and (Horvat) Mezudat Hunin in Modern Hebrew, was built in two phases by the Crusaders during the 12th and 13th centuries (1105/7, 1178 and 1240) and refortified by Mamluk sultan Baibars in 1266.[8] Very little of the medieval structures is preserved.[8]

Ottoman period

The castle was rebuilt in the 18th century[8] by Zahir al-Umar, Bedouin ruler of the Galilee.

In 1752, a mosque was constructed in Hunin. The dedicatory inscription has been tentatively read as saying that the prayer house was consecrated to Ja'far al-Sadiq, the sixth Shia Imam.[9][10]

The village was badly damaged in the earthquake of 1837, according to Edward Robinson who visited in 1856.[11] In 1875, Victor Guérin visited Hunin.[12]

In 1881, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine described Hunin as "[a] village, built of stone, joining on to ruined Crusading castle [..], and containing about 100 Moslems. The situation is on a low ridge just before the hills drop down to the east to the Huleh Valley; the hills round are uncultivated, covered with low scrub, but in the valleys there is some arable land. Water is obtained from numerous cisterns; a birket [pool, reservoir[13]] and spring to the south-east."[14][15]

British Mandate period

The Syria-Lebanon-Palestine boundary was a product of the post-World War I Anglo-French partition of Ottoman Syria.[16][17] British forces had advanced to a position at Tel Hazor against Turkish troops in 1918 and wished to incorporate all the sources of the River Jordan within British-controlled Palestine. Following the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, and the unratified and later annulled Treaty of Sèvres, stemming from the San Remo conference, the 1920 boundary extended the British-controlled area to north of the Sykes-Picot line, a straight line between the midpoint of the Sea of Galilee and Nahariya. The international boundary between Palestine and Lebanon was finally agreed upon by Great Britain and France in 1923, in conjunction with the Treaty of Lausanne, after Britain had been given a League of Nations mandate for Palestine in 1922.[18]

In April 1924, Hunin and six other Shiite villages, and an estimated 20 other settlements, were transferred from the French Mandate of Lebanon to the British Mandate of Palestine by France.[19][20]

In the 1931 census of Palestine, the population of Hunin was 1,075, all Muslims, in a total of 233 houses.[21]

In the 1945 statistics the population of Hunin (with Hula and Udeisa) was 1620 Muslims,[3] with a total of 14,224 dunams of land.[4] Of this, Arabs used 859 for plantations and irrigated land, 5,987 dunums were allocated to grain farming,[3][22] while 81 dunams were classified as urban land.[3][23]

In 1945, Kibbutz Misgav Am was established on what was traditionally the northern part of village land.[5]

1948 and aftermath

A Palmach raid in May 1948 led to many of the inhabitants fleeing to Lebanon, leaving 400 in the village.[24] Four village women were raped and murdered by Israeli soldiers during the summer.[24]

During a meeting in August 1948, the mukhtars of Hunin and other Shi'ite villages met with the Jews of kibbutz Kfar Giladi, declaring their willingness to be good citizens of Israel.[6][24] Their proposal was conveyed to the Israeli government, where it received enthusiastic support from the Minorities Minister Bechor-Shalom Sheetrit.[6][20] A report was made by the Ministry of Minority Affairs recommending that such an agreement be reached with the 4,700 or so Shi'ites in the region to promote friendly relations with southern Lebanon, to take advantage of the Shi'ites' poor relationship with the majority Sunnis, and to enhance the prospect of a future extension of the border.[19] This proposal was not accepted, despite the support of the Minister of Minority Affairs, Sheetrit.[19] In August, more inhabitants of Hunin were forced to flee by the IDF.[25] On 3 September 1948, the IDF raided the village blowing up 20 houses, killing a son of the mukhtar and 19 others and expelling the remaining villagers.[20][24] Most of the villagers took refuge in Shiite villages in Lebanon.[20]

In 1951, Moshav Margaliot was established just south of the village site.[5]

See also

- Hula massacre (31 October - 1 November 1948) perpetrated by the IDF in Hula, a Lebanese Shi'a village 3 km from Hunin

- Shia villages in Palestine

References

- Palmer, 1881, p. 21

- Morris, 2004, p. xvi, village #6. Also gives causes of depopulation.

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 9

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 69

- Khalidi, 1992, p. 455

- Gelber, 2006, p. 222

- Hunin Fortress:Preliminary plan for conservation and development

- Pringle, Denys (1997). Qal'at Hunin (No. 164). Secular Buildings in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: An Archaeological Gazetteer. Cambridge University Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780521460101. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- Sharon, 2007, pp. 108-112

- Sharon, 2013, p. 289

- Robinson, 1856, pp. 370-371

- Guérin, 1880, pp. 370-372

- Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p. 87

- Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, pp. 123-125

- Fromkin, 1989, p. ?

- MacMillan, 2001, pp. 392–420

- Exchange of Notes Archived 2008-09-09 at the Wayback Machine Constituting an Agreement respecting the boundary line between Syria and Palestine from the Mediterranean to El Hammé. Paris, March 7, 1923.

- Sindawi, Khalid (2008). Are there any Shi'te Muslims in Israel?", Holy Land Studies, Vol. 7, No. 2, 183–199.

- Asher Kaufman (2006). "Between Palestine and Lebanon: Seven Shi'i Villages as a Case Study of Boundaries, Identities, and Conflict". Middle East Journal. 60 (4): 685–706.

- Mills, 1932, p. 107

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 119

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 169

- Morris, 2004, pp. 249, 447–448

- Morris, 2004, p. 249

Bibliography

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 1. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Fromkin, D. (1989). A Peace to End All Peace. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-8050-8809-0.

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Gelber, Y. (2006). Palestine 1948: War, Escape And The Emergence Of The Palestinian Refugee Problem (2 ed.). Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 1-84519-075-0.

- Guérin, V. (1880). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 3: Galilee, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- MacMillan, M. (2001). Peacemakers: the Paris Conference of 1919 and its attempt to end war. John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-6237-2.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). I. Oxford University Press. pp. 150−151. ISBN 978-0-19-727011-0.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1856). Later Biblical Researches in Palestine and adjacent regions: A Journal of Travels in the year 1852. London: John Murray.

- Sharon, M. (1999). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, B-C. 2. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-11083-6.p. 49

- Sharon, M. (2007). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, Addendum. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-15780-4.

- Sharon, M. (2013). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, H-I. 5. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-25097-2.

External links

- Welcome to Hunin

- Hunin, Zochrot

- Hunin, Villages of Palestine

- Survey of Western Palestine, map 2: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Hunin, from the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center