John Evelyn

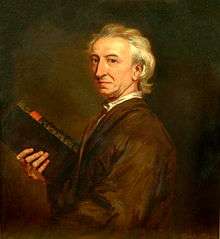

John Evelyn FRS (31 October 1620 – 27 February 1706) was an English writer, gardener and diarist.

John Evelyn's diary, or memoir, spanned the period of his adult life from 1640, when he was a student, to 1706, the year he died. He did not write daily at all times. The many volumes provide insight into life and events at a time before regular magazines or newspapers were published, making diaries of greater interest to modern historians than such works might have been at later periods. Evelyn's work covers art, culture and politics, including the execution of Charles I, Oliver Cromwell's rise and eventual natural death, the last Great Plague of London, and the Great Fire of London in 1666.

Evelyn's posthumously "rival" diarist, Samuel Pepys, wrote a different kind of diary, covering a much shorter period, 1660–1669, but in much greater depth, within the same era. Over the years, Evelyn's Diary has been overshadowed by Pepys's chronicles of 17th-century life.[1]

Biography

Born into a family whose wealth was largely founded on gunpowder production, John Evelyn was born in Wotton, Surrey, and grew up living with his grandparents in Lewes, Sussex.[2] While living in Lewes, in Southover Grange, he was educated at Lewes Old Grammar School,[3] refusing to be sent to Eton College.[4] After this he was educated at Balliol College, Oxford, and at the Middle Temple. In London, he witnessed important events such as the trials and executions of William Howard, 1st Viscount Stafford, and Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford.

In 1640 his father died, and in July 1641 he crossed to Holland. He was enrolled as a volunteer, and then encamped before Genep, on the Waal river, but his military experience was limited to six days of camp life, during which, however, he took his turn at "trailing a pike." He returned in the autumn to find England on the verge of civil war.[4] Having briefly joined the Royalist army and arrived too late for the Royalist victory at the Battle of Brentford in 1642,[5] he spent some time improving his brother's property at Wotton,[4] but then went abroad to avoid further involvement in the English Civil War.[6]

In October 1644 Evelyn visited the Roman ruins in Fréjus, Provence, before travelling on to Italy.[7] He attended anatomy lectures in Padua in 1646 and sent the Evelyn Tables back to London. These are thought to be the oldest surviving anatomical preparations in Europe; Evelyn later gave them to the Royal Society, and they are now in the Hunterian Museum. In 1644, Evelyn visited the English College at Rome, where Catholic priests were trained for service in England. In the Veneto he renewed his acquaintance with the famous art collector Thomas Howard, 21st Earl of Arundel, and toured the art collections of Venice with Arundel's grandson and heir, later Duke of Norfolk. He acquired an ancient Egyptian stela and sent a sketch back to Rome, which was published by Father Kircher, SJ, in Kircher's Oedipus Aegyptiacus (1650), albeit without acknowledgement to Evelyn.[8]

In Florence he commissioned the John Evelyn Cabinet (1644–46), an elaborate ebony cabinet with pietra dura and gilt-bronze panels, which is now in the Victoria and Albert Museum. It was in his London house at his death, then returned to Wotton, and is very likely the "ebony cabinet" in which his diaries were later found.

In 1647 Evelyn married Mary Browne, daughter of Sir Richard Browne, the English ambassador in Paris.[9] During the next few years he travelled back and forth between France and England, corresponding with Browne in the royalist interest, including a meeting with Charles I in 1647.

In 1651 he became convinced that the royalist cause was hopeless, and decided to return to England.[10] The following year, the couple settled in Deptford (present-day south-east London). Their house, Sayes Court (adjacent to the naval dockyard), was purchased by Evelyn from his father-in-law in 1653; Evelyn soon began to transform the gardens. In 1671, he encountered master wood-worker Grinling Gibbons (who was renting a cottage on the Sayes Court estate) and introduced him to Sir Christopher Wren. There is now an electoral ward called Evelyn in Deptford, London Borough of Lewisham. He remained a royalist, had refused employment from the government of the Commonwealth, and had maintained a cipher correspondence with Charles II; in 1659 he published an Apology for the Royal Party.[10]

It was after the Restoration that Evelyn's career really took off, and he enjoyed unbroken court favour until his death. He never held any important political office, although he filled many useful and minor posts. In 1660, he was a member of the group that founded the Royal Society. The following year, he wrote the Fumifugium (or The Inconveniencie of the Aer and Smoak of London Dissipated), the first book written on the growing air pollution problem in London. He was commissioner for improving the streets and buildings of London, for examining into the affairs of charitable foundations, commissioner of the Royal Mint, and of foreign plantations. During the Second Anglo-Dutch War, beginning 28 October 1664, Evelyn served as one of four Commissioners for taking Care of Sick and Wounded Seamen and for the Care and Treatment of Prisoners of War (others included Sir William D'Oyly and Sir Thomas Clifford)., staying at his post during the Great Plague in 1665. He found it impossible to secure sufficient money for the proper discharge of his functions, and in 1688 he was still petitioning for payment of his accounts in this business. He briefly acted as one of the commissioners of the privy seal. In 1695 he was entrusted with the office of treasurer of Greenwich hospital for retired sailors, and laid the first stone of the new building on 30 June 1696.[10]

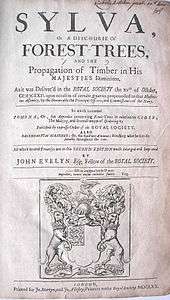

He was known for his knowledge of trees, and had a friend and correspondent, Philip Dumaresq, who "devoted most of his time to gardening, fruit, and tree culture."[11] Evelyn's treatise, Sylva, or A Discourse of Forest-Trees (1664), was written as an encouragement to landowners to plant trees to provide timber for England's burgeoning navy. Further editions appeared in his lifetime (1670 and 1679), with the fourth edition (1706) appearing just after his death and featuring the engraving of Evelyn shown on this page (below) even though it had been made more than 50 years prior by Robert Nanteuil in 1651 in Paris. Various other editions appeared in the 18th and 19th centuries and feature an inaccurate portrait of Evelyn made by Francesco Bartolozzi.

Evelyn had some training as a draftsman and artist, and created several etchings. Most of his published work, produced in the form of drawings to be engraved by others, was to illustrate his own work.

Following the Great Fire in 1666, closely described in his diaries, Evelyn presented the first of several plans (Christopher Wren produced another) for the rebuilding of London, all of which were rejected by Charles II largely due to the complexities of land ownership in the city. He took an interest in the rebuilding of St Paul's Cathedral by Wren (with Gibbons' artistry a notable addition). Evelyn's interest in gardens even led him to design pleasure gardens, such as those at Euston Hall.

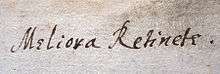

Evelyn was a prolific author and produced books on subjects as diverse as theology, numismatics, politics, horticulture, architecture and vegetarianism, and he cultivated links with contemporaries across the spectrum of Stuart political and cultural life. In September 1671 he travelled with the Royal court of Charles II to Norwich where he called upon Sir Thomas Browne. Like Browne and Pepys, Evelyn was a lifelong bibliophile, and by his death his library is known to have comprised 3,859 books and 822 pamphlets. Many were uniformly bound in a French taste and bear his motto Omnia explorate; meliora retinete ("explore everything; keep the better") from I Thessalonians 5, 21.

His daughter, Mary Evelyn (1665–1685), has been acknowledged as the pseudonymous author of the book Mundus Muliebris of 1690. Mundus Muliebris: or, The Ladies Dressing Room Unlock'd and Her Toilette Spread. In Burlesque. Together with the Fop-Dictionary, Compiled for the Use of the Fair Sex is a satirical guide in verse to Francophile fashion and terminology, and its authorship is often jointly credited to John Evelyn,[12] who seems to have edited the work for press after his daughter's death.

In 1694 Evelyn moved back to Wotton, Surrey, as his elder brother, George, had no living sons available to inherit the estate. Evelyn inherited the estate and the family seat Wotton House on the death of his brother in 1699.[13] Sayes Court was made available for rent. Its most notable tenant was Russian Tsar Peter the Great, who lived there for three months in 1698 (and did great damage to both house and grounds).[10] The house no longer exists, but a public park of the same name can be found off Evelyn Street.[14]

Evelyn died in 1706 at his house in Dover Street, London. Wotton House and estate were inherited by his grandson John (1682–1763) later Sir John Evelyn, Bt.

Family

John and Mary Evelyn had eight children:

- Richard (1652–1658)

- John Standsfield (1653–1654)

- John (the younger) (1655–1699)

- George (1657–1658)

- Richard II (1664)

- Mary (1665–1685)

- Elizabeth (1667–1685)

- Susanna (1669–1754). Only Susanna outlived her parents.

Mary Evelyn died in 1709, three years after her husband. Both are buried in the Evelyn Chapel in St John's Church, Wotton.

Evelyn's epitaph (original spelling) reads:

Here lies the Body of JOHN EVELYN Esq of this place, second son of RICHARD EVELYN Esq who having served the Publick in several employments of which that Commissioner of the Privy Seal in the reign of King James the 2nd was most Honourable: and perpetuated his fame by far more lasting Monuments than those of Stone, or Brass: his Learned and useful works, fell asleep the 27th day of February 1705/6 being the 86th Year of his age in full hope of a glorious resurrection thro faith in Jesus Christ. Living in an age of extraordinary events, and revolutions he learnt (as himself asserted) this truth which pursuant to his intention is here declared. That all is vanity which is not honest and that there's no solid Wisdom but in real piety.

Of five Sons and three Daughters borne to him from his most vertuous and excellent Wife MARY sole daughter, and heiress of Sir RICHARD BROWNE of Sayes Court near Deptford in Kent onely one Daughter SUSANNA married to WILLIAM DRAPER Esq of Adscomb in this County survived him – the two others dying in the flower of their age, and all the sons very young except one nam'd John who deceased 24 March 1698/9 in the 45th year of his age, leaving one son JOHN and one daughter ELIZABETH.

Wotton House and estate passed down to Evelyn's great-great-grandson Sir Frederick Evelyn, 3rd Bt (1733–1812). The baronetcy next passed to Frederick Evelyn's cousins, Sir John Evelyn, 4th Bt (1757–1833), and Sir Hugh Evelyn, 5th Bt (1769–1848). Both these two were of unsound mind and the estate was therefore left to a remote cousin descended from the diarist's grandfather's first marriage, in whose family it remains to this day though they no longer occupy the house. The title died out in 1848. However, there are many living descendants of John Evelyn through his daughter Susanna, Mrs William Draper, and his granddaughter Elizabeth, Mrs Simon Harcourt. There are many descendants of John Evelyn's great-great-grandson, Charles Evelyn Jnr, through his daughter Susanna Prideaux (Evelyn) Wright living in New Zealand. Charles Evelyn Jnr was also the father of Sir John Evelyn, 4th Bt, and the last baronet, Sir Hugh Evelyn, 5th Bt.

In 1992 the skulls of John and Mary were stolen by persons unknown who hacked into the stone sarcophagi on the chapel floor and tore open the coffins. They have not been recovered.

Works

Evelyn's Diary remained unpublished as a manuscript until 1818. It is in a quarto volume containing 700 pages, covering the years between 1641 and 1697, and is continued in a smaller book – which brings the narrative down to within three weeks of its author's death. Despite entries going back to 1641, Evelyn only actually started writing his diary much later, relying on almanacs and accounts of other people for many of the earlier events. A selection from this was edited by William Bray, with the permission of the Evelyn family, in 1818, under the title of Memoirs illustrative of the Life and Writings of John Evelyn, comprising his Diary from 1641 to 1705/6, and a Selection of his Familiar Letters. Other editions followed, the most notable being those of H. B. Wheatley (1879) and Austin Dobson (3 vols, 1906).[10]

Evelyn's active mind produced many other works, and although these have been overshadowed by the famous Diary they are of considerable interest. They include:[10]

- Of Liberty and Servitude ... (1649), a translation from the French of François de la Mothe le Vayer, Evelyn's own copy of which contains a note that he was "like to be call'd in question by the Rebells for this booke";

- The State of France, as it stood in the IXth year of ... Louis XIII (1652), a pamphlet drawn up from personal observations about the royal family, the court, the officials, the military forces, the institutions and customs of France;

- An Essay on the First Book of T. Lucretius Carus de Rerum Natura. Interpreted and made English verse by J. Evelyn (1656); to his translation, Evelyn attached a commentary based on the writings of Gassendi and other philosophical atomists ;

- The Golden Book of St John Chrysostom, concerning the Education of Children. Translated out of the Greek by J. E. (printed 1658, dated 1659);

- The French Gardener: Instructing How to Cultivate all sorts of Fruit-Trees, and Herbs for the Garden (1658), translated from the French of Nicolas de Bonnefons;

- A Character of England, As it was lately presented in a Letter to a Nobleman of France (1659), a satire describing the customs of the country as they would appear to a foreign observer, reprinted in Somers' Tracts (ed. Scott, 1812), and in the Harleian Miscellany (ed. Park, 1813);

- The Late Newes, or Message from Bruxels Unmasked, and his Majesty Vindicated ... (1660), in answer to a libellous pamphlet on Charles I by Marchamont Nedham;

- Fumifugium: or The Inconvenience of the Aer and Smoak of London Dissipated (1661), in which he suggested that sweet-smelling trees should be planted in London to purify the air;

- Instructions Concerning Erecting of a Library ... (1661), from the French of Gabriel Naudé;

- Tyrannus or the Mode, in a Discourse of Sumptuary Laws (1661);

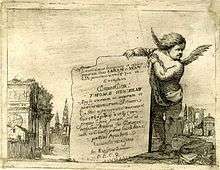

- Sculptura: or the History, and Art of Chalcography and Engraving in Copper... (1662); this contains the first account of "A new manner of Engraving, or Mezzo Tinto, communicated by his Highnesse Prince Rupert to the Author of this Treatise". In fact many think Rupert, who had played a part in the invention or perfecting of mezzotint, wrote or co-wrote this part. The frontispiece "invented" (designed) by Evelyn demonstrates his limitations as an artist of the figure, unless he was badly let down by his engraver.

- Sylva, or a Discourse of Forest Trees and the Propagation of Timber in His Majesties Dominions to which is annexed Pomona ... Also Kalendarium Hortense ... (1664); the best known of his books; a plea for reafforestation aimed at landowners ;

- A Parallel of the Antient Architecture with the Modern (1664), from the French of Roland Fréart, to which was added an Account of Architects and Architecture from Evelyn's own pen ;

- An Idea of the Perfection of Painting: Demonstrated From the Principles of Art, and by Examples (1668), a translation of another work by Roland Fréart;

- The History of the three late famous Imposters, viz. Padre Ottomano, Mahomed Bei, and Sabatei Sevi ... (1669);

- Navigation and Commerce, in which his Majesties title to the Dominion of the Sea is asserted against the Novel and later Pretenders (1674), which is a preface to a projected history of the Dutch wars undertaken at the request of Charles II., but countermanded on the conclusion of peace;

- A Philosophical Discourse of Earth ... (1676), a treatise on horticulture, better known by its later title of Terra; The Compleat Gardener (1693), from the French of J. de la Quintinie;

- Numismata. A Discourse of Medals, Antient and Modern... To which is added a Disgression concerning Physiognomy (1697);

- Acetaria: A Discourse of Sallets... (1699), the first recorded book on salads.

Some of these were reprinted in The Miscellaneous Writings of John Evelyn, edited (1825) by William Upcott.[10]

Evelyn's friendship with Margaret Blagge, afterwards Mrs Godolphin, is recorded in the diary, when he says he designed "to consecrate her worthy life to posterity". This he effectually did in a little masterpiece of religious biography which remained in manuscript in the possession of the Harcourt family until it was edited by Samuel Wilberforce, bishop of Oxford, as the Life of Mrs Godolphin (1847), reprinted in the "King's Classics" (1904). The picture of Mistress Blagge's saintly life at court is heightened in interest when read in connexion with the scandalous memoirs of the comte de Gramont, or contemporary political satires on the court.[10]

Numerous other papers and letters of Evelyn on scientific subjects and matters of public interest are preserved, including a collection of private and official letters and papers (1642–1712) by, or addressed to, Sir Richard Browne and his son-in-law, now held by the British Library (Add. MSS. 15857 and 15858).[10]

In the opinion of the author of his biography in the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, next to the Diary Evelyn's most valuable work is Sylva. Evelyn believed that the country was being rapidly depleted of wood by industries such as glass factories and iron furnaces, while no attempt was being made to replace the damage by planting. In "Sylva", Evelyn pleaded for afforestation and asserted in his preface to the king that he had induced landowners to plant millions of trees.[10] It was a valuable work on arboriculture containing many engravings [15] of trees and their foliage to assist with identification.

Legacy

In 1977 and 1978 in eight auctions at Christie's, a major surviving portion of Evelyn's library was sold and dispersed.[16] The British Library holds a large archive of Evelyn's personal papers including the manuscript of his Diary.[17] The Victoria and Albert Museum has in its collection a cabinet owned by Evelyn which is thought to have housed his diaries. In 2005, a new biography by Gillian Darley, based on full access to the archive, was published.[18] In 2011 a campaign was started to restore John Evelyn's garden in Deptford.[19] William Arthur Evelyn was a descendant.

Things named for Evelyn include:

- Evelyn, London, an electoral ward of the London Borough of Lewisham covering Deptford where John Evelyn lived.

- Evelyn College for Women, the short-lived co-ordinate college of Princeton University, USA[20]

- A house at Addey and Stanhope School in London, England

- Crabtree & Evelyn, the skincare company[21]

- Evelyn, the gossip column of Oxford student newspaper Cherwell

- Evelyn Street, a road in Deptford

- John Evelyn Primary School on the corner of Rolt Street, Deptford.

- The John Evelyn public house on Evelyn Street in Deptford (as featured in the BBC Television's The Tower)

- The Evelyn community garden, Windlass Place, Deptford

References

- Chris Roberts, Heavy Words Lightly Thrown: The Reason Behind Rhyme, Thorndike Press, 2006 (ISBN 0-7862-8517-6)

- The Kalendarium, edited by E.S. de Beer, Oxford Standard Authors Series, 1959, p. 5: "1625. I was this yeare [...] sent by my Father to Lewes in Sussex, to be wih my Grandfather, wih whom I pass'd my Child-hood."

- The Kalendarium, p. 6: "[1630] For I was now put to shoole to one Mr. Potts in the Cliff; from whom on the 7th of Jan: [...] I went to the Free-schole at Southover neere the Towne, of which one Agnes Morley had been the Foundresse, and now Edw: Snatt the Master, under whom I remain'd till I was sent to the University."

- Chisholm 1911, p. 5.

- The Kalendarium, p. 3: "[He] came in with [his] horse and Armes just at the retreate."

- The Kalendarium, p. 47: "finding it impossible to evade the doing of very unhandsome things" [...], "[he] obtayn'd a Lycense of his Majestie [...] to travell againe."

- Ted Jones (15 December 2007). The French Riviera: A Literary Guide for Travellers. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. pp. xx–. ISBN 978-1-84511-455-8.

- Edward Chaney, The Grand Tour and the Great Rebellion (Geneva, 1985); idem, The Evolution of the Grand Tour (London, 2000), idem, "Evelyn, Inigo Jones, and the Collector Earl of Arundel", John Evelyn and his Milieu, eds. F. Harris and M. Hunter (British Library, 2003) and Edward Chaney, "Roma Britannica and the Cultural Memory of Egypt: Lord Arundel and the Obelisk of Domitian", Roma Britannica: Art Patronage and Cultural Exchange in Eighteenth-Century Rome, eds. D. Marshall, K. Wolfe and S. Russell, British School at Rome, 2011, pp. 147–70

- Douglas D. C. Chambers, 'Evelyn, John (1620–1706)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edn, January 2008, accessed 13 January 2008.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 6.

-

- The Miscellaneous Writings of John Evelyn Esq FRS

- English Heritage, Wotton House, BritishListedBuildings.co.uk, retrieved 10 October 2016

- This is the house that Peter the Great destroyed while visiting

- "Examples of engravings from Sylva at Fine Rare Prints".

- Christie, Manson & Woods Ltd. (1977) The Evelyn Library: Sold by Order of the Trustees of the Wills of J. H. C. Evelyn, deceased and Major Peter Evelyn, deceased.

- The John Evelyn archives at the British Library

- "Open Letters Monthly: An Arts and Literature Review » Wider Stranger Worlds". Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- See http://www.sayescourtgarden.org.uk/ Archived 26 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Leitch, Alexander (1978), A Princeton Companion, Princeton University Press

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Sources

- John Evelyn, ed. Guy de la Bédoyère (1997), Particular Friends: The Correspondence of Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn, Boydell and Brewer, ISBN 0-85115-697-5

- John Evelyn, ed. Guy de la Bédoyère (1995), The Writings of John Evelyn, Boydell and Brewer, ISBN 0-85115-631-2 (full annotated texts of several of Evelyn's books and tracts; the only modern collected edition)

- John Evelyn, The Diary of John Evelyn (excerpts)

- John Evelyn, Diaries and Correspondence, Vol 1 - Vol 2 - Vol 3 - Vol 4, edited by William Bray. London: George Bell and Sons, 1882.

- Darley, Gillian (2006). John Evelyn: Living for Ingenuity. Yale: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11227-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Evelyn. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: John Evelyn |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Works by John Evelyn at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about John Evelyn at Internet Archive

- The History of the Evelyn Family by Helen Evelyn, London 1915

- Evelyn family tree

- "Archival material relating to John Evelyn". UK National Archives.

- The John Evelyn archives at the British Library

- Who was John Evelyn? by Guy de la Bédoyère

- John Evelyn's Diary On-Line A Page-per-Day Display with Search Engine

- London's Lost Garden about John Evelyn's gardens, especially Sayes Court.