Energy policy

Energy policy is the manner in which a given entity (often governmental) has decided to address issues of energy development including energy production, distribution and consumption. The attributes of energy policy may include legislation, international treaties, incentives to investment, guidelines for energy conservation, taxation and other public policy techniques. Energy is a core component of modern economies. A functioning economy requires not only labor and capital but also energy, for manufacturing processes, transportation, communication, agriculture, and more. Energy sources are measured in different physical units: liquid fuels in barrels or gallons, natural gas in cubic feet, coal in short tons, and electricity in kilowatts and kilowatthours.

Background

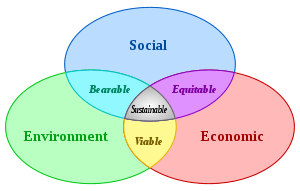

Concerning the term of energy policy, the importance of implementation of an eco-energy-oriented policy at a global level to address the issues of global warming and climate changes should be accentuated.[1]

Although research is ongoing, the "human dimensions" of energy use are of increasing interest to business, utilities, and policymakers. Using the social sciences to gain insights into energy consumer behavior can empower policymakers to make better decisions about broad-based climate and energy options. This could facilitate more efficient energy use, renewable energy commercialization, and carbon emission reductions.[2] Access to energy is also critical for basic social needs, such as lighting, heating, cooking, and health care. As a result, the price of energy has a direct effect on jobs, economic productivity and business competitiveness, and the cost of goods and services.

Private Energy Policy

Private Energy policy refers to a company’s approach to energy. In 2019, some companies “have committed to set climate targets across their operations and value chains aligned with limiting global temperature rise to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and reaching net-zero emissions by no later than 2050”.[3]

National energy policy

Measures used to produce an energy policy

A national energy policy comprises a set of measures involving that country's laws, treaties and agency directives. The energy policy of a sovereign nation may include one or more of the following measures:

- statement of national policy regarding energy planning, energy generation, transmission and usage

- legislation on commercial energy activities (trading, transport, storage, etc.)

- legislation affecting energy use, such as efficiency standards, emission standards

- instructions for state-owned energy sector assets and organizations

- active participation in, co-ordination of and incentives for mineral fuels exploration (see geological survey) and other energy-related research and development policy command

- fiscal policies related to energy products and services (taxes, exemptions, subsidies ...

- energy security and international policy measures such as:

- international energy sector treaties and alliances,

- general international trade agreements,

- special relations with energy-rich countries, including military presence and/or domination.

Frequently the dominant issue of energy policy is the risk of supply-demand mismatch (see: energy crisis). Current energy policies also address environmental issues (see: climate change), particularly challenging because of the need to reconcile global objectives and international rules with domestic needs and laws.[4] Some governments state explicit energy policy, but, declared or not, each government practices some type of energy policy. Economic and energy modelling can be used by governmental or inter-governmental bodies as an advisory and analysis tool (see: economic model, POLES).

Factors within an energy policy

There are a number of elements that are naturally contained in a national energy policy, regardless of which of the above measures was used to arrive at the resultant policy. The chief elements intrinsic to an energy policy are:

- What is the extent of energy self-sufficiency for this nation

- Where future energy sources will derive

- How future energy will be consumed (e.g. among sectors)

- What fraction of the population will be acceptable to endure energy poverty

- What are the goals for future energy intensity, ratio of energy consumed to GDP

- What is the reliability standard for distribution reliability

- What environmental externalities are acceptable and are forecast

- What form of "portable energy" is forecast (e.g. sources of fuel for motor vehicles)

- How will energy efficient hardware (e.g. hybrid vehicles, household appliances) be encouraged

- How can the national policy drive province, state and municipal functions

- What specific mechanisms (e.g. taxes, incentives, manufacturing standards) are in place to implement the total policy

- What future consequences there will be for national security and foreign policy[5]

State, province or municipal energy policy

Even within a state it is proper to talk about energy policies in plural. Influential entities, such as municipal or regional governments and energy industries, will each exercise policy. Policy measures available to these entities are lesser in sovereignty, but may be equally important to national measures. In fact, there are certain activities vital to energy policy which realistically cannot be administered at the national level, such as monitoring energy conservation practices in the process of building construction, which is normally controlled by state-regional and municipal building codes (although can appear basic federal legislation).

America

Brazil

Brazil is the 10th largest energy consumer in the world and the largest in South America. At the same time, it is an important oil and gas producer in the region and the world's second largest ethanol fuel producer. The governmental agencies responsible for energy policy are the Ministry of Mines and Energy (MME), the National Council for Energy Policy (CNPE, in the Portuguese-language acronym), the National Agency of Petroleum, Natural Gas and Biofuels (ANP) and the National Agency of Electricity (ANEEL).[6][7] State-owned companies Petrobras and Eletrobrás are the major players in Brazil's energy sector.[8]

Canada

United States

Currently, the major issues in U.S. energy policy revolve around the rapidly growing production of domestic and other North American energy resources. The U.S. drive toward energy independence and less reliance on oil and coal is fraught with partisan conflict because these issues revolve around how best to balance both competing values, such as environmental protection and economic growth, and the demands of rival organized interests, such as those of the fossil fuel industry and of the newer renewable energy businesses. The Energy Policy Act (EPA) addresses energy production in the United States, including: (1) energy efficiency; (2) renewable energy; (3) oil and gas; (4) coal; (5) Tribal energy; (6) nuclear matters and security; (7) vehicles and motor fuels, including ethanol; (8) hydrogen; (9) electricity; (10) energy tax incentives; (11) hydropower and geothermal energy; and (12) climate change technology.[9] In the United States, British thermal units (Btu), a measure of heat energy, is commonly used for comparing different types of energy to each other. In 2018, total U.S. primary energy consumption was equal to about 101,251,057,000,000,000 British thermal units (Btu), or about 101.3 quadrillion Btu.

Europe

European Union

Although the European Union has legislated, set targets, and negotiated internationally in the area of energy policy for many years, and evolved out of the European Coal and Steel Community, the concept of introducing a mandatory common European Union energy policy was only approved at the meeting of the European Council on October 27, 2005 in London. Following this the first policy proposals, Energy for a Changing World, were published by the European Commission, on January 10, 2007. The most well known energy policy objectives in the EU are 20/20/20 objectives, binding for all EU Member States. The EU is planning to increase the share of renewable energy in its final energy use to 20%, reduce greenhouse gases by 20% and increase energy efficiency by 20%.[10]

Germany

In September 2010, the German government adopted a set of ambitious goals to transform their national energy system and to reduce national greenhouse gas emissions by 80 to 95% by 2050 (relative to 1990).[11] This transformation become known as the Energiewende. Subsequently, the government decided to the phase-out the nation's fleet of nuclear reactors, to be complete by 2022.[12] As of 2014, the country is making steady progress on this transition.[13]

United Kingdom

The energy policy of the United Kingdom has achieved success in reducing energy intensity (but still relatively high), reducing energy poverty, and maintaining energy supply reliability to date. The United Kingdom has an ambitious goal to reduce carbon dioxide emissions for future years, but it is unclear whether the programs in place are sufficient to achieve this objective (the way to be so efficient as France is still hard). Regarding energy self sufficiency, the United Kingdom policy does not address this issue, other than to concede historic energy self sufficiency is currently ceasing to exist (due to the decline of the North Sea oil production). With regard to transport, the United Kingdom historically has a good policy record encouraging public transport links with cities, despite encountering problems with high speed trains, which have the potential to reduce dramatically domestic and short-haul European flights. The policy does not, however, significantly encourage hybrid vehicle use or ethanol fuel use, options which represent viable short term means to moderate rising transport fuel consumption. Regarding renewable energy, the United Kingdom has goals for wind and tidal energy. The White Paper on Energy, 2007, set the target that 20% of the UK's energy must come from renewable sources by 2020.

The Soviet Union and Russia

The Soviet Union was the largest energy provider in the world until the late 1980s. Russia, one of the world's energy superpowers, is rich in natural energy resources, the world’s leading net energy exporter, and a major supplier to the European Union. The main document defining the energy policy of Russia is the Energy Strategy, which initially set out policy for the period up to 2020, later was reviewed, amended and prolonged up to 2030. While Russia has also signed and ratified the Kyoto Protocol. Numerous scholars note that Russia uses its energy exports as a foreign policy instrument towards other countries.[14][15]

Switzerland

In September 2016, both chambers of the Swiss Parliament voted for the Energiestrategie 2050, a set of measures to replace electrical energy produced by atomic reactors with renewable energy, reduce the use of fossil fuel and increase the efficiency of energy consumption. This decision was challenged by a national Referendum.

In May 2017, the Swiss people voted against the Referendum, thereby confirming the decision taken by the parliament.[16]

Turkey

Turkey is trying to secure national energy supply and reduce imports, as in the 2010s fossil fuel costs were a large part of Turkey's import bill. This includes using energy efficiently. However, as of 2019, little research has been done on the policies Turkey uses to reduce energy poverty, which also include some subsidies for home heating and electricity use. The energy strategy includes "within the context of sustainable development, giving due consideration to environmental concerns all along the energy chain". Turkey's energy policy has been criticised for not looking much beyond 2023, not sufficiently involving the private sector, and for being inconsistent with Turkey's climate policy.

Asia

China

The energy policy of China is connected to its industrial policy. The goals of China’s industrial policy dictate its energy needs.[17]

India

The energy policy of India is characterized by trades between four major drivers:

- Rapidly growing economy, with a need for dependable and reliable supply of electricity, gas, and petroleum products;[18]

- Increasing household incomes, with a need for affordable and adequate supply of electricity, and clean cooking fuels;

- Limited domestic reserves of fossil fuels, and the need to import a vast fraction of the gas, crude oil, and petroleum product requirements, and recently the need to import coal as well; and

- Indoor, urban and regional environmental impacts, necessitating the need for the adoption of cleaner fuels and cleaner technologies.

In recent years, these challenges have led to a major set of continuing reforms, restructuring and a focus on energy conservation.

Thailand

The energy policy of Thailand is characterized by 1) increasing energy consumption efficiency, 2) increasing domestic energy production, 3) increasing the private sector's role in the energy sector, 4) increasing the role of market mechanisms in setting energy prices. These policies have been consistent since the 1990s, despite various changes in governments. The pace and form of industry liberalization and privatization has been highly controversial.

Bangladesh

The first National Energy Policy (NEP) of Bangladesh was formulated in 1996 by the Ministry of Power, Energy and Mineral resources to ensure proper exploration, production, distribution and rational use of energy resources to meet the growing energy demands of different zones, consuming sectors and consumers groups on a sustainable basis.[1] With rapid change of global as well as domestic situation, the policy was updated in 2004. The updated policy included additional objectives namely to ensure environmentally sound sustainable energy development programmes causing minimum damage to environment, to encourage public and private sector participation in the development and management of energy sector and to bring the entire country under electrification by the year 2020.[2]

Oceania

Australia

Australia's energy policy features a combination of coal power stations and hydro electricity plants. The Australian government has decided not to build nuclear power plants, although it is one of the world's largest producers of uranium.

See also

- Energy: world resources and consumption

- Energy balance

- Energy and society

- Energy law

- Energie-Cités

- Environmental policy

- Nuclear energy policy

- Oil Shockwave

- RELP Renewable Energy Law and Policy Review

- Renewable energy policy

- World Forum on Energy Regulation (WFER)

- All pages with titles containing Energy policy of

References

- Eraldo Banovac, Marinko Stojkov, Dražan Kozak. Designing a global energy policy model, Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Energy, Vol 170, Issue 1, February, 2017, pp. 2-11. https://doi.org/10.1680/jener.16.00005.

- Robert C. Armstrong, Catherine Wolfram, Robert Gross, Nathan S. Lewis, and M.V. Ramana et al., "The Frontiers of Energy", Nature Energy, Vol 1, 11 January 2016.

- "87 Major Companies Lead the Way Towards a 1.5°C Future at UN Climate Action Summit". UNFCCC. 22 September 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Farah, Paolo Davide; Rossi, Piercarlo (December 2, 2011). "National Energy Policies and Energy Security in the Context of Climate Change and Global Environmental Risks: A Theoretical Framework for Reconciling Domestic and International Law Through a Multiscalar and Multilevel Approach". European Energy and Environmental Law Review. 2 (6): 232–244. SSRN 1970698.

- Hamilton, Michael S. 2013. Energy Policy Analysis: A Conceptual Framework. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, Inc.

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2006. ISBN 92-64-10989-7

- "Project Closing Report. Natural Gas Centre of Excellence Project. Narrative" (PDF). 20 March 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-05-12.

- Silvestre, B. S., Dalcol, P. R. T. Geographical proximity and innovation: Evidences from the Campos Basin oil & gas industrial agglomeration — Brazil. Technovation (2009), doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2009.01.003

- "Summary of the Energy Policy Act". EPA.gov. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Obrecht, Matevz; Denac, Matjaz (2013). "A sustainable energy policy for Slovenia : considering the potential of renewables and investment costs". Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy. 5 (3): 032301. doi:10.1063/1.4811283.

- Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology (BMWi); Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU) (28 September 2010). Energy concept for an environmentally sound, reliable and affordable energy supply (PDF). Berlin, Germany: Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology (BMWi). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 2016-05-01.

- Bruninx, Kenneth; Madzharov, Darin; Delarue, Erik; D'haeseleer, William (2013). "Impact of the German nuclear phase-out on Europe's electricity generation — a comprehensive study". Energy Policy. 60: 251–261. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2013.05.026. Retrieved 2016-05-12.

- The Energy of the Future: Fourth "Energy Transition" Monitoring Report — Summary (PDF). Berlin, Germany: Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi). November 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-09-20. Retrieved 2016-06-09.

- Baran, Z. (2007). EU Energy Security: Time to End Russian Leverage.The Washington Quarterly, 30(4), 131–144.

- Robert Orttung and Indra Overland (2011) ‘A Limited Toolbox: Explaining the Constraints on Russia’s Foreign Energy Policy’, Journal of Eurasian Studies, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 74-85. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/251718767

- Energy Strategy 2050. Swiss Federal Department of the Environment, Transport, Energy and Communications DETEC. Retrieved 2020-01-11.

- Rosen, Daniel; Houser, Trevor (May 2007). "China Energy A Guide for the Perplexed" (PDF). piie.com. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- Lathia, Rutvik Vasudev; Dadhaniya, Sujal (February 2017). "Policy formation for Renewable Energy sources". Journal of Cleaner Production. 144: 334–336. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.01.023.

Further reading

- Eraldo Banovac, Marinko Stojkov, Dražan Kozak. Designing a global energy policy model, Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Energy, Vol 170, Issue 1, February, 2017, pp. 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1680/jener.16.00005

- Armstrong, Robert C., Catherine Wolfram, Robert Gross, Nathan S. Lewis, and M.V. Ramana et al. The Frontiers of Energy, Nature Energy, Vol 1, 11 January 2016.

- Deitchman, Benjamin H. Climate and Clean Energy Policy: State Institutions and Economic Implications. Routledge, 2016.

- Hughes, Llewelyn; Lipscy, Phillip (2013). "The Politics of Energy" (PDF). Annual Review of Political Science. 16: 449–469. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-072211-143240.

- Fouquet, Roger, and Peter JG Pearson. "Seven Centuries of Energy Services: The Price and Use of Light in the United Kingdom (1300-2000)." Energy Journal 27.1 (2006).

- Gales, Ben; et al. (2007). "North versus South: Energy transition and energy intensity in Europe over 200 years" (PDF). European Review of Economic History. 11 (2): 219–253. doi:10.1017/s1361491607001967.

- Lifset, Robert, ed. American Energy Policy in the 1970s (University of Oklahoma Press; 2014) 322 pages;

- Nye, David E. Consuming power: A social history of American energies (MIT Press, 1999)

- Pratt, Joseph A. Exxon: Transforming Energy, 1973-2005 (2013) 600pp

- Smil, Vaclav (1994). Energy in World History. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-1902-5.

- Stern, David I (2011). "The role of energy in economic growth" (PDF). Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1219 (1): 26–51. Bibcode:2011NYASA1219...26S. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05921.x. PMID 21332491. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-29.

- Warr, Benjamin; et al. (2010). "Energy use and economic development: A comparative analysis of useful work supply in Austria, Japan, the United Kingdom and the US during 100 years of economic growth" (PDF). Ecological Economics. 69 (10): 1904–1917. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.03.021.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Energy policy. |

- "Geopolitics of EU energy supply", Euractiv, July 2005

- "Ifri Energy Program", Ifri

- "Our energy future - creating a low carbon economy", UK, February 2003

- Final report on the Green Paper "Towards a European strategy for the security of energy supply", EU, June 2004

- "Energy Policies of (Country x)" series, International Energy Agency

- Report of President Bush's National Energy Policy Group, May 2001

- Yahoo News Full Coverage: Energy Policy

- UN-Energy - Global energy policy co-ordination

- Energy & Environmental Security Initiative (EESI)

- Renewable Energy Policy Network (REN21)

- An interesting discussion of CO2 emissions from the Center for Global Studies

- Information on energy institutions, policies and local energy companies by country, Enerdata Publications

- Energy Policy in Germany Website from Deutsche Welle-TV about the German "Energiewende"