Angling

Angling is a method of fishing by means of an "angle" (fish hook). The hook is usually attached to a fishing line and the line is often attached to a fishing rod. Modern fishing rods are usually fitted with a fishing reel that functions as a mechanism for storing, retrieving and paying out the line. Tenkara fishing and cane pole fishing are two techniques that do not use a reel. The hook itself can be dressed with bait, but sometimes a lure, with hooks attached to it, is used in place of a hook and bait. A bite indicator such as a float, and a weight or sinker are sometimes used.

_(8465260282).jpg)

Angling is the principal method of sport fishing, but commercial fisheries also use angling methods such as longlining or trolling. Catch and release fishing is increasingly practiced by recreational fishermen. In many parts of the world, size limits apply to certain species, meaning fish below and/or above a certain size must, by law, be released.

The species of fish pursued by anglers vary with geography. Among the many species of salt water fish that are caught for sport are swordfish, marlin, tuna, while in Europe cod and bass are popular targets. In North America the most popular fresh water sport species include bass, pike, walleye, muskellunge, yellow perch, trout, salmon, crappie, bluegill and sunfish. In Europe many anglers fish for species such as carp, pike, tench, rudd, roach, European perch, catfish and barbel.

Hooks

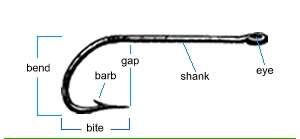

The use of the hook in angling is descended, historically, from what would today be called a "gorge." The word "gorge", in this context, comes from the French word meaning "throat." Gorges were used by ancient peoples to capture fish and animals like seal, walrus and birds. A gorge was a long, thin piece of bone or stone attached by its midpoint to a thin line. The gorge would be baited so that it would rest parallel to the lay of the line. When the game would swallow the bait, a tug on the line would cause the gorge to orient itself at right angles to the line, thereby sticking in the fish or animal's throat or gullet. Gorges evolved into the modern fishing hook which is a J shaped wire with a loop on one end and a sharp point on the other. Most hooks have a barb near the point to prevent a fish from unhooking itself while being reeled in. Some laws and regulations require hooks to be barbless. This rule is commonly implemented to protect populations of certain species. A barbed hook could kill a fish if it were to penetrate the gills.

Baits

Which of the various techniques an angler may choose is dictated mainly by the target species and by its habitat. Angling can be separated into two main categories: using either artificial or natural baits.

Artificial baits

Many people prefer to fish solely with lures, which are artificial baits designed to entice fish to strike. The artificial bait angler uses a man-made lure that may or may not represent prey. The lure may require a specialised presentation to impart an enticing action as, for example, in fly fishing. A common way to fish a soft plastic worm is the Texas Rig.

Natural baits

The natural bait angler, with few exceptions, will use a common prey species of the fish as an attractant. The natural bait used may be alive or dead. Common natural baits for both fresh and saltwater fishing include worms, leeches, minnows, frogs, salamanders, octopus, squid, insects and even prawn . Natural baits are effective due to the real texture, odour and colour of the bait presented.

The common earthworm is a universal bait for fresh water angling. Grubs and maggots are also excellent bait when trout fishing. Grasshoppers, bees and even ants are also used as bait for trout in their season, although many anglers believe that trout or salmon roe is superior to any other bait. In lakes in southern climates such as Florida, fish such as sunfish will even take bread as bait. Bread bait is a small amount of bread, often moistened by saliva, balled up to a small size that is bite size to small fish.

Spreading disease

The capture, transportation and culture of bait fish can spread damaging organisms between ecosystems, endangering them. In 2007 several American states enacted regulations designed to slow the spread of fish diseases, including viral hemorrhagic septicemia, by bait fish.[1] Because of the risk of transmitting Myxobolus cerebralis (whirling disease), trout and salmon should not be used as bait.

Anglers may increase the possibility of contamination by emptying bait buckets into fishing venues and collecting or using bait improperly. The transportation of fish from one location to another can break the law and cause the introduction of fish alien to the ecosystem.

Laws and regulations

Laws and regulations managing angling vary greatly, often regionally, within countries. These commonly include permits (licences), closed periods (seasons) where specific species are unavailable for harvest, restrictions on gear types, and quotas.

Laws generally prohibit catching fish with hooks other than in the mouth (foul hooking, "snagging" or "jagging"[2]) or the use of nets other than as an aid in landing a captured fish. Some species, such as bait fish, may be taken with nets, and a few for food. Sometimes, (non-sport) fish are considered of lesser value and it may be permissible to take them by methods like snagging, bow and arrow, or spear. None of these techniques fall under the definition of angling since they do not rely upon the use of a hook and line.

Fishing seasons

Fishing seasons are set by countries or localities to indicate what kinds of fish may be caught during sport fishing (also known as angling) for a certain period of time. Fishing seasons are enforced to maintain ecological balance and to protect species of fish during their spawning period during which they are easier to catch.

Slot limits

Slot limits are put in action to help protect certain fish in given area. They generally require anglers to release captured fish if they fall within a given size range, allowing anglers to keep only smaller or larger fish.[3][4] Slot Limits vary from lake to lake depending on what local officials believe would produce the best outcome for managing fish populations.

Catch and release

Although most anglers keep their catch for consumption, catch and release fishing is increasingly practiced, especially by fly anglers. The general principle is that releasing fish allows them to survive, thus avoiding unintended depletion of the population. For species such as marlin, muskellunge, and bass, there is a cultural taboo among anglers against taking them for food. In many parts of the world, size limits apply to certain species, meaning fish below a certain size must, by law, be released. It is generally believed that larger fish have a greater breeding potential. Some fisheries have a slot limit that allows the taking of smaller and larger fish, but requiring that intermediate sized fish be released. It is generally accepted that this management approach will help the fishery create a number of large, trophy-sized fish. In smaller fisheries that are heavily fished, catch and release is the only way to ensure that catchable fish will be available from year to year. The practice of catch and release is criticised by some who consider it unethical to inflict pain upon a fish for purposes of sport. Some of those who object to releasing fish do not object to killing fish for food. Adherents of catch and release dispute this charge, pointing out that fish commonly feed on hard and spiky prey items, and as such can be expected to have tough mouths, and also that some fish will re-take a lure they have just been hooked on, a behaviour that is unlikely if hooking were painful. Opponents of catch and release fishing would find it preferable to ban or to severely restrict angling. On the other hand, proponents state that catch-and-release is necessary for many fisheries to remain sustainable, is a practice that generally has high survival rates, and consider the banning of angling as not reasonable or necessary.[5]

In some jurisdictions, in the Canadian province of Manitoba, for example, catch and release is mandatory for some species such as brook trout. Many of the jurisdictions which mandate the live release of sport fish also require the use of artificial lures and barbless hooks to minimise the chance of injury to fish. Mandatory catch and release also exists in the Republic of Ireland where it was introduced as a conservation measure to prevent the decline of Atlantic salmon stocks on some rivers.[6] In Switzerland, catch and release fishing is considered inhumane and was banned in September 2008.[7]

Barbless hooks, which can be created from a standard hook by removing the barb with pliers or can be bought, are sometimes resisted by anglers because they believe that increased fish escapes. Barbless hooks reduce handling time, thereby increasing survival. Concentrating on keeping the line taut while fighting fish, using recurved point or "triple grip" style hooks on lures, and equipping lures that do not have them with split rings can significantly reduce escapement.

Capacity for pain

Animal protection advocates have raised concerns about the suffering of fish caused by angling. In light of recent research, some countries, like Germany, have banned specific types of fishing and the British RSPCA now formally prosecutes individuals who are cruel to fish.[8]

Experiments done by William Tavolga provide evidence that fish have pain and fear responses. For instance, in Tavolga's experiments, toadfish grunted when electrically shocked and over time they came to grunt at the mere sight of an electrode.[9] Additional tests conducted at both the University of Edinburgh and the Roslin Institute, in which bee venom and acetic acid was injected into the lips of rainbow trout, resulted in fish rubbing their lips along the sides and floors of their tanks, which the researchers believe was an effort to relieve themselves of pain.[10] One researcher argues about the definition of pain used in the studies.[11]

In 2003, Scottish scientists at the University of Edinburgh performing research on rainbow trout concluded that fish exhibit behaviors often associated with pain, and the brains of fish fire neurons in the same way human brains do when experiencing pain.[12][13] James D. Rose of the University of Wyoming critiqued the study, claiming it was flawed, mainly since it did not provide proof that fish possess "conscious awareness, particularly a kind of awareness that is meaningfully like ours".[14] Rose argues that since the fish brain is rather different from ours, fish are not conscious, whence reactions similar to human reactions to pain instead have other causes. Rose had published his own opinion a year earlier arguing that fish cannot feel pain as they lack the appropriate neocortex in the brain.[15] However, animal behaviorist Temple Grandin argues that fish could still have consciousness without a neocortex because "different species can use different brain structures and systems to handle the same functions."[13] The position that Rose takes also fails to address unresolved empirical and philosophical considerations concerning pain, as raised by principles of epistemology,[16] solipsism, existentialism, and comparative ethology.[17] Until such problems are far more fundamentally resolved, there are strong arguments for refraining from causing the appearance of pain or behaviour consistent with pain, insofar as such things might be reasonably avoidable.[18] However, in 2012, a group of researchers led by Rose reviewed the literature, and concluded again that fish are not conscious and therefore do not feel pain.[19]

Tournaments and derbies

Sometimes considered within the broad category of angling is where contestants compete for prizes based on the total length or weight of a fish, usually of a pre-determined species, caught within a specified time (fishing tournaments). Such contests have evolved from local fishing contests into large competitive circuits, where professional anglers are supported by commercial endorsements. Professional anglers are not engaged in commercial fishing, even though they gain an economic reward. Similar competitive fishing exists at the amateur level with fishing derbies. In general, derbies are distinguished from tournaments; derbies normally require fish to be killed. Tournaments normally deduct points if fish can not be released alive.

Motivation

A ten-year-long survey of US fishing club members, completed in 1997, indicated that motivations for recreational angling have shifted from relaxation, an outdoor experience and the experience of the catch, to the importance of family recreation. Anglers with higher family incomes fished more frequently and were less concerned about obtaining fish as food.[20]

A German study indicated that satisfaction derived from angling was not dependent on the actual catch, but depended more on the angler's expectations of the experience.[21]

A 2006 study by the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries tracked the motivations of anglers on the Red River. Among the most often stated responses were the fun of catching fish, the experience, to catch a lot of fish or a very large fish, for challenge, and adventure. Use as food was not investigated as a motive.[22]

See also

- Bamboo fly rods

- Bibliography of fly fishing

- Gaff

- Piscatorial Society

- Tailrace fishing

- Trolling (fishing)

- Trout worms

References

- DNR Fishing Regulation Changes Reflect Disease Management Concerns with VHS Archived 2008-12-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Illegal fishing methods NSW Government Industry and Investment. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- "Fishing limits - What is a slot limit?". Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Archived from the original on 8 December 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- "What are slot limits?". Kansas Department of Wildlife, Parks and Tourism. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- Understanding the Complexity of Catch and Release in Recreational Fishing: An Integrative Synthesis of Global Knowledge from Historical, Ethical, Social, and Biological Perspectives Published in Reviews in Fisheries Science, Volume 15, Issue 1 & 2 January 2007, pages 75 - 167 Authors: Robert Arlinghaus; Steven J. Cooke; Jon Lyman; David Policansky; Alexander Schwab; Cory Suski; Stephen G. Sutton; Eva B. Thorstad

- Fishing in Ireland Catch and Release for Atlantic Salmon

- Animal Rights Law Passed in Switzerland - Catch and Release Fishing Banned

- "Anglers to Face RSPCA Check", Sunday Times, 14 March 2004

- Dunayer, Joan, "Fish: Sensitivity Beyond the Captor's Grasp," The Animals' Agenda, July/August 1991, pp. 12-18

- Vantressa Brown, “Fish Feel Pain, British Researchers Say,” Agence France-Presse, 1 May 2003

- “Do fish have nociceptors: Evidence for the evolution of a vertebrate sensory system”, 2003 by Sneddon, Braithwaite and Gentle. A critique of the paper by James D. Rose, Ph.D. Department of Zoology and Physiology University of Wyoming Archived May 17, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- "Fish do feel pain, scientists say". BBC News. 2003-04-30. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- Grandin, Temple; Johnson, Catherine (2005). Animals in Translation. New York, New York: Scribner. pp. 183–184. ISBN 978-0-7432-4769-6.

- Rose, J.D. 2003. A Critique of the paper: "Do fish have nociceptors: Evidence for the evolution of a vertebrate sensory system" Archived March 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- James D. Rose, Do Fish Feel Pain? Archived November 29, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, 2002. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- Smullyan, Raymond (1984). Five thousand b.c. & other philosophical fantasies. S.l: Palgrave. ISBN 978-0-312-29517-2.

- Hofstadter, Douglas (1981). The mind's I : fantasies and reflections on self and soul. Brighton, Sussex, England: Harvester Press. ISBN 978-0-7108-0352-8.

- Newall, Charles F. "The problem of pain in nature." Publisher: Paisley : Alexander Gardner (1917). May be downloaded from: https://archive.org/details/problemofpaininn00newauoft

- Rose, J. D.; Arlinghaus, R.; Cooke, S. J.; Diggles, B. K.; Sawynok, W.; Stevens, E. D.; Wynne, C D L. (December 2012). "Can fish really feel pain?". Fish and Fisheries. 15: 97–133. doi:10.1111/faf.12010. S2CID 43948913.

- Schramm, H. L.; Gerard, P. D. (2004). "Temporal changes in fishing motivation among fishing club anglers in the United States – Abstract". Fisheries Management and Ecology. 11 (5): 313. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2400.2004.00384.x. Archived from the original on 2013-01-05. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- Arlinghaus, Robert (2006). "On the apparently striking disconnect between motivation and satisfaction in recreational fishing : the case of catch orientation of german anglers". North American Journal of Fisheries Management. 26 (3): 592–605. doi:10.1577/M04-220.1. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- Yeong Nain Chi Socioeconomic Research and Development Section Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. "Segmenting Fishing Markets Using Motivations" (PDF). e-Review of Tourism Research (eRTR), Vol. 4, No.3, 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Angling. |

| Wikisource has original works on the topic: Angling |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: River Fishing |

- Project Gutenberg: The Compleat Angler

- How to fish taken from the Boy's Own Book of Outdoor Sports (early 1900s)