Shetland

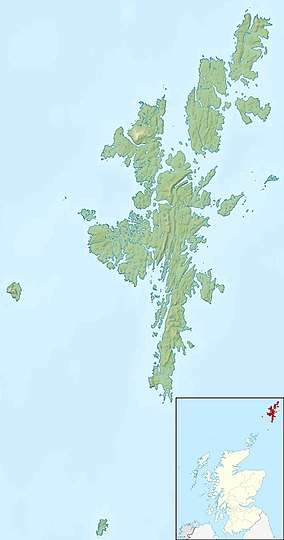

Shetland (Scottish Gaelic: Sealtainn Scottish Gaelic pronunciation: [ˈʃalˠ̪t̪ɪɲ]; Old Norse: Hjaltland; Scots: Shetland), also called the Shetland Islands and formerly Zetland, is a subarctic archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated in the Northern Atlantic, between Great Britain, the Faroe Islands and Norway.

| Norse name | Hjaltland |

|---|---|

| Meaning of name | 'Hiltland' |

| Location | |

| |

Shetland Shetland shown within Scotland | |

| OS grid reference | HU4363 |

| Coordinates | 60°21′N 1°13′W |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Northern Isles |

| Area | 1,466 km2 (566 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | Ronas Hill 450 m (1,480 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | Shetland Islands Council |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 22,920 (2019) |

| Population density | 15/km2 (40/sq mi) |

| Largest settlement | Lerwick |

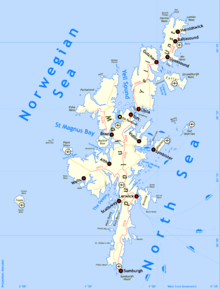

The islands lie some 80 km (50 mi) to the northeast of Orkney, 170 km (110 mi) from the Scottish mainland and 300 km (190 mi) west of Norway. They form part of the division between the Atlantic Ocean to the west and the North Sea to the east. The total area is 1,466 km2 (566 sq mi),[1] and the population totalled 22,920 in 2019.[2] The islands comprise the Shetland constituency of the Scottish Parliament. The local authority, Shetland Islands Council, is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland. The islands' administrative centre and only burgh is Lerwick, which has been the capital of Shetland since taking over from Scalloway in 1708.

The largest island, known as "Mainland", has an area of 967 km2 (373 sq mi), making it the third-largest Scottish island[3] and the fifth-largest of the British Isles. There are an additional 15 inhabited islands. The archipelago has an oceanic climate, a complex geology, a rugged coastline and many low, rolling hills.

Humans have lived in Shetland since the Mesolithic period. The early historic period was dominated by Scandinavian influences, especially from Norway. The islands became part of Scotland in the 15th century. When Scotland became part of the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707, trade with northern Europe decreased. Fishing continues to be an important aspect of the economy up to the present day. The discovery of North Sea oil in the 1970s significantly boosted Shetland's economy, employment and public sector revenues.

The local way of life reflects the Scottish and Norse heritage of the isles, including the Up Helly Aa fire festival and a strong musical tradition, especially the traditional fiddle style. The islands have produced a variety of writers of prose and poetry, often in the distinct Shetland dialect of the Scots language. There are numerous areas set aside to protect the local fauna and flora, including a number of important sea bird nesting sites. The Shetland pony and Shetland Sheepdog are two well-known Shetland animal breeds. Other local breeds include the Shetland sheep, cow, goose, and duck. The Shetland pig, or grice, has been extinct since about 1930.

The islands' motto, which appears on the Council's coat of arms, is "Með lögum skal land byggja". The Old Norse origin of this phrase is likely from the Norwegian provincial laws, such as the Frostathing Law. It is also mentioned in Njáls saga, and means "By law shall land be built".

Etymology

The name of Shetland is derived from the Old Norse words, hjalt ('hilt'), and land ('land').[4][5]

In AD 43 and 77 the Roman authors Pomponius Mela and Pliny the Elder referred to seven islands they respectively called Haemodae and Acmodae, both of which are assumed to be Shetland. Another possible early written reference to the islands is Tacitus' report in Agricola in AD 98. After describing the discovery and conquest of Orkney, he wrote that the Roman fleet had seen "Thule, too".[Note 1] In early Irish literature, Shetland is referred to as Insi Catt—"the Isles of Cats", which may have been the pre-Norse inhabitants' name for the islands. The Cat clan also occupied parts of the northern Scottish mainland (see Kingdom of Cat); and their name can be found in Caithness and in the Scottish Gaelic name for Sutherland (Cataibh, meaning "among the Cats").[8][Note 2]

The oldest version of the modern name Shetland is Hetlandensis, the Latinised adjectival form of the Old Norse name, recorded in a letter from Harald, Count of Shetland, in 1190,[10] becoming Hetland in 1431 after various intermediate transformations. It is possible that the Pictish "cat" sound forms part of this Norse name. It then became Hjaltland in the 16th century.[11][12][Note 3]

As Norn was gradually replaced by Scots in the form of the Shetland dialect, Hjaltland became Ȝetland. The initial letter is the Middle Scots letter, yogh, the pronunciation of which is almost identical to the original Norn sound, /hj/. When the use of the letter yogh was discontinued, it was often replaced by the similar-looking letter z (which at the time was usually rendered with a curled tail: ⟨ʒ⟩) hence Zetland, the form used in the name of the pre-1975 county council.[13][14] This is also the source of the ZE postcode used for Shetland.

Most of the individual islands have Norse names, although the derivations of some are obscure and may represent pre-Norse, possibly Pictish or even pre-Celtic names or elements.[15]

Geography and geology

.jpg)

Shetland is around 170 kilometres (110 mi) north of mainland Scotland, covers an area of 1,468 square kilometres (567 sq mi) and has a coastline 2,702 kilometres (1,679 mi) long.[1]

Lerwick, the capital and largest settlement, has a population of 6,958 and about half of the archipelago's total population of 22,920 people[2] live within 16 kilometres (10 mi) of the town.[16]

Scalloway on the west coast, which was the capital until 1708, has a population of less than 1,000.[17]

Only 16 of about 100 islands are inhabited. The main island of the group is known as Mainland. The next largest are Yell, Unst, and Fetlar, which lie to the north, and Bressay and Whalsay, which lie to the east. East and West Burra, Muckle Roe, Papa Stour, Trondra and Vaila are smaller islands to the west of Mainland. The other inhabited islands are Foula 28 kilometres (17 mi) west of Walls, Fair Isle 38 kilometres (24 mi) south-west of Sumburgh Head, and the Out Skerries to the east.[Note 4]

The uninhabited islands include Mousa, known for the Broch of Mousa, the finest preserved example in Scotland of an Iron Age broch; Noss to the east of Bressay, which has been a national nature reserve since 1955; St Ninian's Isle, connected to Mainland by the largest active tombolo in the UK; and Out Stack, the northernmost point of the British Isles.[18][19][20] Shetland's location means that it provides a number of such records: Muness is the most northerly castle in the United Kingdom and Skaw the most northerly settlement.[21]

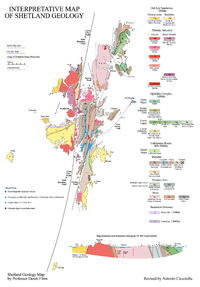

The geology of Shetland is complex, with numerous faults and fold axes. These islands are the northern outpost of the Caledonian orogeny, and there are outcrops of Lewisian, Dalradian and Moine metamorphic rocks with histories similar to their equivalents on the Scottish mainland. There are also Old Red Sandstone deposits and granite intrusions. The most distinctive feature is the ophiolite in Unst and Fetlar which is a remnant of the Iapetus Ocean floor made up of ultrabasic peridotite and gabbro.[22]

Much of Shetland's economy depends on the oil-bearing sediments in the surrounding seas.[23] Geological evidence shows that in around 6100 BC a tsunami caused by the Storegga Slides hit Shetland, as well as the rest of the east coast of Scotland, and may have created a wave of up to 25 metres (82 ft) high in the voes where modern populations are highest.[24]

The highest point of Shetland is Ronas Hill at 450 metres (1,480 ft). The Pleistocene glaciations entirely covered the islands. During that period, the Stanes of Stofast, a 2000-tonne glacial erratic, came to rest on a prominent hilltop in Lunnasting.[25]

Shetland has a national scenic area which, unusually, includes a number of discrete locations: Fair Isle, Foula, South West Mainland (including the Scalloway Islands), Muckle Roe, Esha Ness, Fethaland and Herma Ness.[26] The total area covered by the designation is 41,833 ha, of which 26,347 ha is marine (i.e. below low tide).[27]

In October 2018, legislation came into force in Scotland to prevent public bodies, without good reason, showing Shetland in a separate box in maps, as had often been the practice. The legislation requires the islands to be "displayed in a manner that accurately and proportionately represents their geographical location in relation to the rest of Scotland", so as make clear the islands' real distance from other areas.[28][29][30]

Climate

Shetland has an oceanic temperate maritime climate (Köppen: Cfb), bordering on, but very slightly above average in summer temperatures, the subpolar variety, with long but cool winters and short mild summers. The climate all year round is moderate owing to the influence of the surrounding seas, with average night-time low temperatures a little above 1 °C (34 °F) in January and February and average daytime high temperatures of near 14 °C (57 °F) in July and August.[31] The highest temperature on record was 28.0 °C (82.4 °F) on the 6th of August 1910[32] and the lowest −8.9 °C (16.0 °F) in the Januaries of 1952 and 1959.[33] The frost-free period may be as little as three months.[34] In contrast, inland areas of nearby Scandinavia on similar latitudes experience significantly larger temperature differences between summer and winter, with the average highs of regular July days comparable to Lerwick's all-time record heat that is around 23 °C (73 °F), further demonstrating the moderating effect of the Atlantic Ocean. In contrast, winters are considerably milder than those expected in nearby continental areas, even comparable to winter temperatures of many parts of England and Wales much further south.

The general character of the climate is windy and cloudy with at least 2 mm (0.08 in) of rain falling on more than 250 days a year. Average yearly precipitation is 1,003 mm (39.5 in), with November and December the wettest months. Snowfall is usually confined to the period November to February, and snow seldom lies on the ground for more than a day. Less rain falls from April to August although no month receives less than 50 mm (2 in). Fog is common during summer due to the cooling effect of the sea on mild southerly airflows.[31][33]

Because of the islands' latitude, on clear winter nights the "northern lights" can sometimes be seen in the sky, while in summer there is almost perpetual daylight, a state of affairs known locally as the "simmer dim".[35] Annual bright sunshine averages 1110 hours, and overcast days are common.[36]

| Climate data for Shetland Isles,82m asl, 1981-2010, extremes 1922- | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 12.8 (55.0) |

11.7 (53.1) |

13.3 (55.9) |

16.1 (61.0) |

20.7 (69.3) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.4 (74.1) |

22.1 (71.8) |

19.4 (66.9) |

17.2 (63.0) |

13.9 (57.0) |

12.3 (54.1) |

23.4 (74.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 5.4 (41.7) |

5.3 (41.5) |

6.3 (43.3) |

8.0 (46.4) |

10.3 (50.5) |

12.6 (54.7) |

14.2 (57.6) |

14.4 (57.9) |

12.7 (54.9) |

10.3 (50.5) |

7.7 (45.9) |

6.2 (43.2) |

9.5 (49.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 3.9 (39.0) |

3.5 (38.3) |

4.2 (39.6) |

5.8 (42.4) |

7.9 (46.2) |

10.1 (50.2) |

12.1 (53.8) |

12.4 (54.3) |

10.8 (51.4) |

8.3 (46.9) |

5.9 (42.6) |

4.3 (39.7) |

7.5 (45.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.4 (34.5) |

1.1 (34.0) |

1.9 (35.4) |

3.0 (37.4) |

5.2 (41.4) |

7.6 (45.7) |

9.6 (49.3) |

9.9 (49.8) |

8.4 (47.1) |

6.3 (43.3) |

3.7 (38.7) |

2.1 (35.8) |

5.3 (41.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −8.9 (16.0) |

−7.4 (18.7) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

3.5 (38.3) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

−8.9 (16.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 142.6 (5.61) |

120.8 (4.76) |

124.6 (4.91) |

70.4 (2.77) |

53.4 (2.10) |

58.2 (2.29) |

66.8 (2.63) |

83.7 (3.30) |

106.3 (4.19) |

141.5 (5.57) |

146.0 (5.75) |

142.6 (5.61) |

1,256.8 (49.48) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 21.6 | 18.5 | 19.9 | 14.1 | 10.8 | 11.0 | 12.1 | 12.9 | 16.7 | 20.8 | 21.4 | 21.8 | 201.6 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 27.2 | 55.2 | 94.1 | 131.8 | 181.0 | 146.2 | 124.4 | 127.9 | 101.3 | 68.8 | 33.8 | 18.1 | 1,109.9 |

| Source: [37][38] | |||||||||||||

Prehistory

Due to the practice, dating to at least the early Neolithic, of building in stone on virtually treeless islands, Shetland is extremely rich in physical remains of the prehistoric eras and there are over 5,000 archaeological sites all told.[40] A midden site at West Voe on the south coast of Mainland, dated to 4320–4030 BC, has provided the first evidence of Mesolithic human activity in Shetland.[41][42] The same site provides dates for early Neolithic activity and finds at Scord of Brouster in Walls have been dated to 3400 BC.[Note 5] "Shetland knives" are stone tools that date from this period made from felsite from Northmavine.[44]

Pottery shards found at the important site of Jarlshof also indicate that there was Neolithic activity there although the main settlement dates from the Bronze Age.[45] This includes a smithy, a cluster of wheelhouses and a later broch. The site has provided evidence of habitation during various phases right up until Viking times.[39][46] Heel-shaped cairns, are a style of chambered cairn unique to Shetland, with a particularly large example in Vementry.[44]

Numerous brochs were erected during the Iron Age. In addition to Mousa there are significant ruins at Clickimin, Culswick, Old Scatness and West Burrafirth, although their origin and purpose is a matter of some controversy.[47] The later Iron Age inhabitants of the Northern Isles were probably Pictish, although the historical record is sparse. Hunter (2000) states in relation to King Bridei I of the Picts in the sixth century AD: "As for Shetland, Orkney, Skye and the Western Isles, their inhabitants, most of whom appear to have been Pictish in culture and speech at this time, are likely to have regarded Bridei as a fairly distant presence.”[48] In 2011, the collective site, "The Crucible of Iron Age Shetland", including Broch of Mousa, Old Scatness and Jarlshof, joined the UKs "Tentative List" of World Heritage Sites.[49][50]

History

Scandinavian colonisation

_with_surrounding_lands.png)

The expanding population of Scandinavia led to a shortage of available resources and arable land there and led to a period of Viking expansion, the Norse gradually shifting their attention from plundering to invasion.[51] Shetland was colonised during the late 8th and 9th centuries,[52] the fate of the existing indigenous population being uncertain. Modern Shetlanders have almost identical proportions of Scandinavian matrilineal and patrilineal genetic ancestry, suggesting that the islands were settled by both men and women in equal measure.[53]

Vikings then used the islands as a base for pirate expeditions to Norway and the coasts of mainland Scotland. In response, Norwegian king Harald Hårfagre ("Harald Fair Hair") annexed the Northern Isles (comprising Orkney and Shetland) in 875.[Note 6] Rognvald Eysteinsson received Orkney and Shetland from Harald as an earldom as reparation for the death of his son in battle in Scotland, and then passed the earldom on to his brother Sigurd the Mighty.[55]

The islands converted to Christianity in the late 10th century. King Olav Tryggvasson summoned the jarl Sigurd the Stout during a visit to Orkney and said, "I order you and all your subjects to be baptised. If you refuse, I'll have you killed on the spot and I swear I will ravage every island with fire and steel." Unsurprisingly, Sigurd agreed and the islands became Christian at a stroke.[56] Unusually, from c. 1100 onwards the Norse jarls owed allegiance both to Norway and to the Scottish crown through their holdings as Earls of Caithness.[57]

In 1194, when Harald Maddadsson was Earl of Orkney and Shetland, a rebellion broke out against King Sverre Sigurdsson of Norway. The Øyskjeggs ("Island Beardies") sailed for Norway but were beaten in the Battle of Florvåg near Bergen. After his victory King Sverre placed Shetland under direct Norwegian rule, a state of affairs that continued for nearly two centuries.[58][59]

Increased Scottish interest

From the mid-13th century onwards Scottish monarchs increasingly sought to take control of the islands surrounding the mainland. The process was begun in earnest by Alexander II and was continued by his successor Alexander III. This strategy eventually led to an invasion of Scotland by Haakon Haakonsson, King of Norway. His fleet assembled in Bressay Sound before sailing for Scotland. After the stalemate of the Battle of Largs, Haakon retreated to Orkney, where he died in December 1263, entertained on his deathbed by recitations of the sagas. His death halted any further Norwegian expansion in Scotland and following this ill-fated expedition, the Hebrides and Mann were yielded to the Kingdom of Scotland as a result of the 1266 Treaty of Perth, although the Scots recognised continuing Norwegian sovereignty over Orkney and Shetland.[60][61][62]

Absorption by Scotland

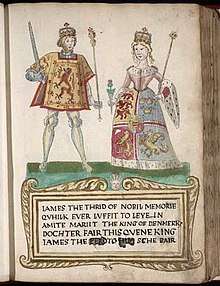

In the 14th century, Orkney and Shetland remained a Norwegian possession, but Scottish influence was growing. Jon Haraldsson, who was murdered in Thurso in 1231, was the last of an unbroken line of Norse jarls,[63] and thereafter the earls were Scots noblemen of the houses of Angus and St Clair.[64] On the death of Haakon VI in 1380,[65] Norway formed a political union with Denmark, after which the interest of the royal house in the islands declined.[58] In 1469, Shetland was pledged by Christian I, in his capacity as King of Norway, as security against the payment of the dowry of his daughter Margaret, betrothed to James III of Scotland. As the money was never paid, the connection with the Crown of Scotland became permanent.[Note 7] In 1470, William Sinclair, 1st Earl of Caithness ceded his title to James III, and the following year the Northern Isles were directly absorbed to the Crown of Scotland,[68] an action confirmed by the Parliament of Scotland in 1472.[69] Nonetheless, Shetland's connection with Norway has proved to be enduring.[Note 8]

From the early 15th century onward Shetlanders sold their goods through the Hanseatic League of German merchantmen. The Hansa would buy shiploads of salted fish, wool and butter, and import salt, cloth, beer and other goods. The late 16th century and early 17th century were dominated by the influence of the despotic Robert Stewart, Earl of Orkney, who was granted the islands by his half-sister Mary Queen of Scots, and his son Patrick. The latter commenced the building of Scalloway Castle, but after his imprisonment in 1609 the Crown annexed Orkney and Shetland again until 1643 when Charles I granted them to William Douglas, 7th Earl of Morton. These rights were held on and off by the Mortons until 1766, when they were sold by James Douglas, 14th Earl of Morton to Laurence Dundas.[70][71]

18th and 19th centuries

The trade with the North German towns lasted until the 1707 Act of Union, when high salt duties prevented the German merchants from trading with Shetland. Shetland then went into an economic depression, as the local traders were not as skilled in trading salted fish. However, some local merchant-lairds took up where the German merchants had left off, and fitted out their own ships to export fish from Shetland to the Continent. For the independent farmers of Shetland this had negative consequences, as they now had to fish for these merchant-lairds.[72]

Smallpox afflicted the islands in the 17th and 18th centuries (as it did all of Europe), but as vaccines became available after 1800, health improved. The islands were very badly hit by the potato famine of 1846 and the government introduced a Relief Plan for the islands under the command of Captain Robert Craigie of the Royal Navy who stayed in Lerwick to oversee the project 1847-1852. During this period Craigie also did much to improve and increase roads in the islands.[73]

Population increased to a maximum of 31,670 in 1861. However, British rule came at price for many ordinary people as well as traders. The Shetlanders' nautical skills were sought by the Royal Navy. Some 3,000 served during the Napoleonic wars from 1800 to 1815 and press gangs were rife. During this period 120 men were taken from Fetlar alone, and only 20 of them returned home. By the late 19th century 90% of all Shetland was owned by just 32 people, and between 1861 and 1881 more than 8,000 Shetlanders emigrated.[74][75] With the passing of the Crofters' Act in 1886 the Liberal prime minister William Gladstone emancipated crofters from the rule of the landlords. The Act enabled those who had effectively been landowners' serfs to become owner-occupiers of their own small farms.[76] By this time fishermen from Holland, who had traditionally gathered each year off the coast of Shetland to fish for herring, triggered an industry in the islands that boomed from around 1880 until the 1920s when stocks of the fish began to dwindle.[77] The production peaked in 1905 at more than a million barrels, of which 708,000 were exported.[78]

20th century

During World War I many Shetlanders served in the Gordon Highlanders, a further 3,000 served in the Merchant Navy, and more than 1,500 in a special local naval reserve. The 10th Cruiser Squadron was stationed at Swarbacks Minn (the stretch of water to the south of Muckle Roe), and during a single year from March 1917 more than 4,500 ships sailed from Lerwick as part of an escorted convoy system. In total, Shetland lost more than 500 men, a higher proportion than any other part of Britain, and there were further waves of emigration in the 1920s and 1930s.[75][80]

During World War II a Norwegian naval unit nicknamed the "Shetland Bus" was established by the Special Operations Executive in the autumn of 1940 with a base first at Lunna and later in Scalloway to conduct operations around the coast of Norway. About 30 fishing vessels used by Norwegian refugees were gathered and the Shetland Bus conducted covert operations, carrying intelligence agents, refugees, instructors for the resistance, and military supplies. It made over 200 trips across the sea, and Leif Larsen, the most highly decorated allied naval officer of the war, made 52 of them.[79][81] Several RAF airfields and sites were also established at Sullom Voe and several lighthouses suffered enemy air attacks.[80]

Oil reserves discovered in the later 20th century in the seas both east and west of Shetland have provided a much-needed alternative source of income for the islands. The East Shetland Basin is one of Europe's largest oil fields and as a result of the oil revenue and the cultural links with Norway, a small Home Rule movement developed briefly to recast the constitutional position of Shetland. It saw as its models the Isle of Man, as well as Shetland's closest neighbour, the Faroe Islands, an autonomous dependency of Denmark.[82]

The population stood at 17,814 in 1961.[83]

Economy

Today, the main revenue producers in Shetland are agriculture, aquaculture, fishing, renewable energy, the petroleum industry (crude oil and natural gas production), the creative industries and tourism.[85]

Fishing

Fishing remains central to the islands' economy today, with the total catch being 75,767 tonnes (74,570 long tons; 83,519 short tons) in 2009, valued at over £73.2 million. Mackerel makes up more than half of the catch in Shetland by weight and value, and there are significant landings of haddock, cod, herring, whiting, monkfish and shellfish.[84]

Energy and fossil fuels

Oil and gas were first landed in 1978 at Sullom Voe, which has subsequently become one of the largest terminals in Europe.[86] Taxes from the oil have increased public sector spending on social welfare, art, sport, environmental measures and financial development. Three quarters of the islands' workforce is employed in the service sector,[87][88] and the Shetland Islands Council alone accounted for 27.9% of output in 2003.[89][90] Shetland's access to oil revenues has funded the Shetland Charitable Trust, which in turn funds a wide variety of local programmes. The balance of the fund in 2011 was £217 million, i.e., about £9,500 per head.[91][Note 9]

In January 2007, the Shetland Islands Council signed a partnership agreement with Scottish and Southern Energy for the Viking Wind Farm, a 200-turbine wind farm and subsea cable. This renewable energy project would produce about 600 megawatts and contribute about £20 million to the Shetland economy per year.[93] The plan met with significant opposition within the islands, primarily resulting from the anticipated visual impact of the development.[94] The PURE project in Unst is a research centre which uses a combination of wind power and fuel cells to create a wind hydrogen system. The project is run by the Unst Partnership, the local community's development trust.[95][96]

Farming and textiles

Farming is mostly concerned with the raising of Shetland sheep, known for their unusually fine wool.[17][97][98]

Knitwear is important both to the economy and culture of Shetland, and the Fair Isle design is well known. However, the industry faces challenges due to plagiarism of the word "Shetland" by manufacturers operating elsewhere, and a certification trademark, "The Shetland Lady", has been registered.[99]

Crofting, the farming of small plots of land on a legally restricted tenancy basis, is still practised and is viewed as a key Shetland tradition as well as an important source of income.[100] Crops raised include oats and barley; however, the cold, windswept islands make for a harsh environment for most plants.

Media

Shetland is served by a weekly local newspaper, The Shetland Times and the online Shetland News [101] with radio service being provided by BBC Radio Shetland and the commercial radio station SIBC.[102]

Tourism

Shetland is a popular destination for cruise ships, and in 2010 the Lonely Planet guide named Shetland as the sixth best region in the world for tourists seeking unspoilt destinations. The islands were described as "beautiful and rewarding" and the Shetlanders as "a fiercely independent and self-reliant bunch".[103] Overall visitor expenditure was worth £16.4 million in 2006, in which year just under 26,000 cruise liner passengers arrived at Lerwick Harbour. This business has grown substantially with 109 cruise ships already booked in for 2019, representing over 107,000 passenger visits.[104] In 2009, the most popular visitor attractions were the Shetland Museum, the RSPB reserve at Sumburgh Head, Bonhoga Gallery at Weisdale Mill and Jarlshof.[105] Geopark Shetland (now Shetland UNESCO Global Geopark) was established by the Amenity Trust in 2009 to boost sustainable tourism to the islands.[106]

Quarries

- Brindister: 60.114475°N 1.215874°W

- Scord: 60.142287°N 1.261629°W Scalloway 05

- Sullom: 60.439953°N 1.382306°W

- Vatster: 60.212887°N 1.220861°W

Transport

Transport between islands is primarily by ferry, and Shetland Islands Council operates various inter-island services.[107] Shetland is also served by a domestic connection from Lerwick to Aberdeen on mainland Scotland. This service, which takes about 12 hours, is operated by NorthLink Ferries. Some services also call at Kirkwall, Orkney, which increases the journey time between Aberdeen and Lerwick by 2 hours.[108][109] There are plans for road tunnels to some of the islands, especially Bressay and Whalsay; however, it is hard to convince the mainland government to finance them.[110]

Sumburgh Airport, the main airport in Shetland, is located close to Sumburgh Head, 40 km (25 mi) south of Lerwick. Loganair operates flights to other parts of Scotland up to ten times a day, the destinations being Kirkwall, Aberdeen, Inverness, Glasgow and Edinburgh.[111] Lerwick/Tingwall Airport is located 11 km (6.8 mi) west of Lerwick. Operated by Directflight Limited in partnership with Shetland Islands Council, it is devoted to inter-island flights from the Shetland Mainland to most of the inhabited islands.[112][113]

Scatsta Airport near Sullom Voe allows frequent charter flights from Aberdeen to transport oilfield workers and this small terminal has the fifth largest number of international passengers in Scotland.[114]

Public bus services are operated in Mainland, Whalsay, Burra, Unst and Yell.[115]

The archipelago is exposed to wind and tide, and there are numerous sites of wrecked ships.[116] Lighthouses are sited as an aid to navigation at various locations.[117]

Public services

The Shetland Islands Council is the Local Government authority for all the islands and is based in Lerwick Town Hall.

Shetland is sub-divided into 18 community council areas[118] and into 12 civil parishes that are used for statistical purposes.[119]

|

.svg.png) Walls and Sandness

|

Education

In Shetland there are two high schools—Anderson and Brae—five junior high schools, and 24 primary schools.[121]

In 2014 there were plans to close other junior high schools and require boarding at Anderson.[122]

Shetland is also home to the North Atlantic Fisheries College, the Centre for Nordic Studies and Shetland College, which are all associated with the University of the Highlands and Islands.[123][124]

Sport

The Shetland Football Association oversees two divisions — a Premier League and a Reserve League — which are affiliated with the Scottish Amateur Football Association.[125] Seasons take place during summer.

The islands are represented by the Shetland football team, which regularly competes in the Island Games.

Churches and religion

The Reformation reached the archipelago in 1560. This was an apparently peaceful transition and there is little evidence of religious intolerance in Shetland's recorded history.[127]

In the 2011 census, Shetland registered a higher proportion of people with no religion than the Scottish average.[126] Nevertheless, a variety of religious denominations are represented in the islands.

The Methodist Church has a relatively high membership in Shetland, which is a District of the Methodist Church (with the rest of Scotland comprising a separate District).[128]

The Church of Scotland has a Presbytery of Shetland that includes St. Columba's Church in Lerwick.[129]

The Catholic population is served by the church of St. Margaret and the Sacred Heart in Lerwick. The Parish is part of the Diocese of Aberdeen.

The Scottish Episcopal Church (part of the Anglican Communion) has regular worship at St Magnus' Church, Lerwick, St Colman's Church, Burravoe, and the Chapel of Christ the Encompasser, Fetlar, the last of which is maintained by the Society of Our Lady of the Isles, the most northerly and remote Anglican religious order of nuns.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has a congregation in Lerwick. The former print works and offices of the local newspaper, The Shetland Times, has been converted into a chapel.

Politics

Shetland is represented in the House of Commons as part of the Orkney and Shetland constituency, which elects one Member of Parliament. Since 2001, the MP has been Alistair Carmichael. This seat has been held by the Liberal Democrats or their predecessors the Liberal Party since 1950, longer than any other seat in the UK.[130][131][132]

In the Scottish Parliament the Shetland constituency elects one Member of the Scottish Parliament (MSP) by the first past the post system. Tavish Scott of the Scottish Liberal Democrats had held the seat since the creation of the Scottish Parliament in 1999.[133] Beatrice Wishart MSP, also of the Scottish Liberal Democrats, was elected to replace Tavish Scott in August 2019.[134] Shetland is within the Highlands and Islands electoral region.

The political composition of the Shetland Islands Council is 21 Independents and 1 Scottish National Party.[135]

In the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence from the United Kingdom, Shetland voted to remain in the UK by the third largest margin of the 32 local authority areas, by 63.71% to 36.29% in favour of the status quo.

The Wir Shetland movement was set up in 2015 to campaign for greater autonomy.[136] As of early 2018, however, the movement appears to be inactive.[137][138]

Shetland flag

Roy Grönneberg, who founded the local chapter of the Scottish National Party in 1966, designed the flag of Shetland in cooperation with Bill Adams to mark the 500th anniversary of the transfer of the islands from Norway to Scotland. The colours are identical to those of the flag of Scotland, but are shaped in the Nordic cross. After several unsuccessful attempts, including a plebiscite in 1985, the Lord Lyon King of Arms approved it as the official flag of Shetland in 2005.[139][Note 10]

Local culture and the arts

After the islands were officially transferred from Norway to Scotland in 1472, several Scots families from the Scottish Lowlands emigrated to Shetland in the 16th and 17th centuries.[140][53] Studies of the genetic makeup of the islands' population, however, indicate that Shetlanders are just under half Scandinavian in origin, and sizeable amounts of Scandinavian ancestry, both patrilineal and matrilineal, have been reported in Orkney (55%) and Shetland (68%).[53] This combination is reflected in many aspects of local life. For example, almost every place name in use can be traced back to the Vikings.[141] The Lerwick Up Helly Aa is one of several fire festivals held in Shetland annually in the middle of winter, starting on the last Tuesday of January.[142] The festival is just over 100 years old in its present, highly organised form. Originally held to break up the long nights of winter and mark the end of Yule, the festival has become one celebrating the isles' heritage and includes a procession of men dressed as Vikings and the burning of a replica longship.[143] Shetland also competes in the biennial International Island Games, which it hosted in 2005.[144]

30Jan1973.jpg)

The cuisine of Shetland is based on locally produced lamb, beef and seafood, much of it organic. Inevitably, the real ale-producing Valhalla Brewery is the most northerly in Britain. The Shetland Black is a variety of blue potato with a dark skin and indigo-coloured flesh markings.[145]

Language

The Norn language was a form of Old Norse spoken in the Northern Isles, and continued to be spoken until the 19th century. It was gradually replaced in Shetland by an insular dialect of Scots, known as Shetlandic, which is in turn being replaced in some areas by Scottish English. Although Norn was spoken for hundreds of years, it is now extinct and few written sources remain, although influences remain in the Insular Scots dialects.[146] Shetland dialect is used in local radio and dialect writing, and is kept alive by organisations such as Shetland Forwirds, Isle Folk, and the Shetland Folk Society.[147][148][149]

Music

Shetland's culture and landscapes have inspired a variety of musicians, writers and film-makers. The Forty Fiddlers was formed in the 1950s to promote the traditional fiddle style, which is a vibrant part of local culture today.[150] Notable exponents of Shetland folk music include Aly Bain, Jenna Reid, Fiddlers' Bid, and the late Tom Anderson and Peerie Willie Johnson. Thomas Fraser was a country musician who never released a commercial recording during his life, but whose work has become popular more than 20 years after his death in 1978.[151]

The annual Shetland Folk Festival began in 1981 and is hosted on the first weekend of May.[152]

Writers

Walter Scott's 1822 novel The Pirate is set in "a remote part of Shetland", and was inspired by his 1814 visit to the islands. The name Jarlshof meaning "Earl's Mansion" is a coinage of his.[153] Robert Cowie, a doctor born in Lerwick published the 1874 work Shetland: Descriptive and Historical; Being a Graduation Thesis on the Inhabitants of the Shetland Islands; and a Topographical Description of the Country. Menzies. 1874.

Hugh MacDiarmid, the Scots poet and writer, lived in Whalsay from the mid-1930s through 1942, and wrote many poems there, including a number that directly address or reflect the Shetland environment, such as "On A Raised Beach", which was inspired by a visit to West Linga.[154] The 1975 novel North Star by Hammond Innes is largely set in Shetland and Raman Mundair's 2007 book of poetry A Choreographer's Cartography offers a British Asian perspective on the landscape.[155] The Shetland Quartet by Ann Cleeves, who previously lived in Fair Isle, is a series of crime novels set around the islands.[156] In 2013 her novel Red Bones became the basis of BBC crime drama television series Shetland.[157]

Vagaland, who grew up in Walls, was arguably Shetland's finest poet of the 20th century.[158] Haldane Burgess was a Shetland historian, poet, novelist, violinist, linguist and socialist, and Rhoda Bulter (1929–94) is one of the best-known Shetland poets of recent times. Other 20th- and 21st-century poets and novelists include Christine De Luca, Robert Alan Jamieson who grew up in Sandness, the late Lollie Graham of Veensgarth, Stella Sutherland of Bressay,[159] the late William J Tait from Yell[160] and Laureen Johnson.[161]

There are two monthly magazines in production: Shetland Life and i'i' Shetland.[162][163] The quarterly The New Shetlander, founded in 1947, is said to be Scotland's longest-running literary magazine.[164] For much of the later 20th century it was the major vehicle for the work of local writers—and of others, including early work by George Mackay Brown.[165]

Films and television

Michael Powell made The Edge of the World in 1937, a dramatisation based on the true story of the evacuation of the last 36 inhabitants of the remote island of St Kilda on 29 August 1930. St Kilda lies in the Atlantic Ocean, 64 kilometres (40 mi) west of the Outer Hebrides but Powell was unable to get permission to film there. Undaunted, he made the film over four months during the summer of 1936 in Foula and the film transposes these events to Shetland. Forty years later, the documentary Return to the Edge of the World was filmed, capturing a reunion of cast and crew of the film as they revisited the island in 1978.

A number of other films have been made on or about Shetland including A Crofter's Life in Shetland (1932)[166] A Shetland Lyric (1934),[167] Devil's Gate (2003) and It's Nice Up North (2006), a comedy documentary by Graham Fellows. The Screenplay film festival takes place annually in Mareel, a cinema, music and education venue.

The BBC One television series Shetland, a crime drama, is set in the islands and is based on the book series by Ann Cleeves. The programme is filmed partly in Shetland and partly on the Scottish mainland.[168][169]

Wildlife

Shetland has three national nature reserves, at the seabird colonies of Hermaness and Noss, and at Keen of Hamar to preserve the serpentine flora. There are a further 81 SSSIs, which cover 66% or more of the land surfaces of Fair Isle, Papa Stour, Fetlar, Noss and Foula. Mainland has 45 separate sites.[170]

Flora

The landscape in Shetland is marked by the grazing of sheep and the harsh conditions have limited the total number of plant species to about 400. Native trees such as rowan and crab apple are only found in a few isolated places such as cliffs and loch islands. The flora is dominated by Arctic-alpine plants, wild flowers, moss and lichen. Spring squill, buck's-horn plantain, Scots lovage, roseroot and sea campion are abundant, especially in sheltered places. Shetland mouse-ear (Cerastium nigrescens) is an endemic flowering plant found only in Shetland. It was first recorded in 1837 by botanist Thomas Edmondston. Although reported from two other sites in the nineteenth century, it currently grows only on two serpentine hills in the island of Unst. The nationally scarce oysterplant is found in several islands and the British Red Listed bryophyte Thamnobryum alopecurum has also been recorded.[171][172][173][174] Listed marine algae include: Polysiphonia fibrillosa (Dillwyn) Sprengel, Polysiphonia atlantica Kapraun and J.Norris, Polysiphonia brodiaei (Dillwyn) Sprengel, Polysiphonia elongata (Hudson) Sprengel, Polysiphonia elongella. Harvey [175] The Shetland Monkeyflower is unique to Shetland and is a mutation of the Monkeyflower (mimulus guttatus) introduced to Shetland in the 19th century.[176][177]

Fauna

.jpg)

Shetland has numerous seabird colonies. Birds found in the islands include Atlantic puffin, storm-petrel, red-throated diver, northern gannet and great skua (locally called the "bonxie").[178] Numerous rarities have also been recorded including black-browed albatross and snow goose, and a single pair of snowy owls bred in Fetlar from 1967 to 1975.[178][179][180] The Shetland wren, Fair Isle wren and Shetland starling are subspecies endemic to Shetland.[181][182] There are also populations of various moorland birds such as curlew, snipe and golden plover.[183]

One of the early ornithologists that wrote about the wealth of birdlife in Shetland was Edmund Selous (1857-1934) in his book The Bird Watcher in the Shetlands (1905).[184] He writes extensively about the gulls and terns, about the arctic skuas, the black guillemots and many other birds (and the seals) of the islands.

The geographical isolation and recent glacial history of Shetland have resulted in a depleted mammalian fauna and the brown rat and house mouse are two of only three species of rodent present in the islands. The Shetland field mouse is the third and the archipelago's fourth endemic subspecies, of which there are three varieties in Yell, Foula and Fair Isle.[182] They are variants of Apodemus sylvaticus and archaeological evidence suggests that this species was present during the Middle Iron Age (around 200 BC to AD 400). It is possible that Apodemus was introduced from Orkney where a population has existed since at the least the Bronze Age.[185]

Domesticated animals

.jpg)

There is a variety of indigenous breeds, of which the diminutive Shetland pony is probably the best known, as well as being an important part of the Shetland farming tradition. The first written record of the pony was in 1603 in the Court Books of Shetland and, for its size, it is the strongest of all the horse breeds.[186][187] Others are the Shetland Sheepdog or "Sheltie", the endangered Shetland cattle[188] and Shetland goose[189][190] and the Shetland sheep which is believed to have originated prior to 1000 AD.[191] The Grice was a breed of semi-domesticated pig that had a habit of attacking lambs. It became extinct sometime between the middle of the nineteenth century and the 1930s.[192]

See also

Lists

- List of counties of the United Kingdom

- List of islands in Scotland

- List of populated places in Shetland

About Shetland

Notes

- Watson (1926) is sure that Tacitus was referring to Shetland, although Breeze (2002) is more sceptical. Thule is first mentioned by Pytheas of Massilia when he visited Britain sometime between 322 and 285 BC, but it is unlikely he meant Shetland as he believed it was six days sail north of Britain and one day from the frozen sea.[6][7]

- The modern Scottish Gaelic name for Shetland, Sealtainn [ˈʃalˠ̪t̪ɪɲ] is derived from the Old Norse dative form Hjaltlandi through, as in Scots Shetland, the process of reverse lenition of the initial /hj/ to /ʃ/.[9] In contrast with Scots, Gaelic has preserved the first l (in hjalt), but the last one (in land) has disappeared.

- As with all western dialects of Norse, the stressed a shifts to e and so the ja became je as with Norse hjalpa which became hjelpa. Then the pronunciation changed through a process of reverse lenition of the initial /hj/ to /ʃ/. This is also found in some Norwegian dialects in for instance the word hjå (with) and the place names Hjerkinn and Sjoa (from *Hjó). Lastly the l before the t disappeared.[5]

- Shetland Islands Council state there are 15 inhabited islands, and count East and West Burra, which are joined by a bridge, as a single unit. Out Skerries has two inhabited islands: Housay and Bruray.[1]

- The Scord of Brouster site includes a cluster of six or seven walled fields and three stone circular houses that contains the earliest hoe-blades found so far in Scotland.[43]

- Some scholars believe that this story, which appears in the Orkneyinga Saga is apocryphal and based on the later voyages of Magnus Barelegs.[54]

- Apparently without the knowledge of the Norwegian Rigsraadet (Council of the Realm), Christian pawned Orkney for 50,000 Rhenish guilders. On 28 May the next year, he also pawned Shetland for 8,000 Rhenish guilders.[66] He had secured a clause in the contract which gave future kings of Norway the right to redeem the islands for a fixed sum of 210 kg of gold or 2,310 kg of silver. Several attempts were made during the 17th and 18th centuries to redeem the islands, without success.[67]

- When Norway became independent again in 1906, the Shetland authorities sent a letter to King Haakon VII in which they stated: "Today no 'foreign' flag is more familiar or more welcome in our voes and havens than that of Norway, and Shetlanders continue to look upon Norway as their mother-land, and recall with pride and affection the time when their forefathers were under the rule of the Kings of Norway."[58]

- No other part of the UK has any such oil-related fund. By comparison, as of 31 December 2010 the total value of the Government Pension Fund of Norway was NOK 3 077 billion ($525 bn),[92] i.e., circa £68,000 per head.

- The flag is the same design Icelandic republicans used in the early 20th century known in Iceland as Hvítbláinn, the "white-blue".[139]

References

- Shetland Islands Council (2012) p. 4

- "Shetland Islands Council Area Profile". National Records of Scotland. April 2020. Archived from the original on 5 May 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 406

- Hjaltland – Shetland – ‘yet, land!” – 1871 Archived 27 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Jakobsen, Jakob, fetlaraerial.com. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- "Placenames with -a, hjalt, Leirvik". Norwegian Language Council. (Norwegian). Retrieved 26 March 2011. Archived version here.

- Breeze, David J. "The ancient geography of Scotland" in Smith and Banks (2002) pp. 11-13.

- Watson (1994) p. 7

- Watson (1994) p. 30

- Oftedal, M. (1956) "The Gaelic of Leurbost". Norsk Tidskrift for Sprogvidenskap. (Norwegian Journal of Linguistics).

- Diplomatarium Norvegicum. p.2 [1190] Dilectissimis amicis suis et hominibus Haraldus Orcardensis, Hetlandensis et Catanesie comes salutem. archive.org

- Gammeltoft (2010) p. 21-22

- Sandnes (2010) p. 9

- Jones (1997) p. 210

- "Zetland County Council" Archived 24 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine shetlopedia.com. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- Gammeltoft (2010) p. 19

- "Visit Shetland". Visit.Shetland.org Retrieved 25 December 2010.

- Shetland Islands Council (2010) p. 10

- Hansom, J.D. (2003) "St Ninian's Tombolo". Archived 23 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine (pdf) Coastal Geomorphology of Great Britain. Geological Conservation Review. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- "Get-a-map". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- Fojut, Noel (1981) "Is Mousa a broch?" Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot. 111 pp. 220-228

- "Skaw (Unst)" Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Shetlopedia. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- Gillen (2003) pp. 90-91

- Keay & Keay (1994) p. 867

- Smith, David "Tsunami hazards". Fettes.com. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- Schei (2006) pp. 103-04

- "Map: Shetland National Scenic Area" (PDF). Scottish Natural Heritage. December 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- "National Scenic Areas - Maps". SNH. 20 December 2010. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- Islands (Scotland) Act 2018 section 17; "Ban on putting Shetland in a box on maps comes into force". BBC News. 4 October 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- Kent, Alexander. "Remapping the Shetland Isles". Expert Comment. Canterbury Christ Church University. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- Kent, Alexander (18 October 2018). "Maps > Representation". The Cartographic Journal. 55 (3): 203–204. doi:10.1080/00087041.2018.1527980. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- "Shetland, Scotland Climate" Archived 18 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine climatetemp.info Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- https://www.trevorharley.com/weather-august.html

- Shetland Islands Council (2005) pp. 5-9

- "Northern Scotland: climate". Met office. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- "The Climate of Shetland". Visit Shetland. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- "Lerwick climate information". Met Office. Archived from the original on 24 January 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- "Shetland in Statistics 2014" (PDF). shetland.gov.uk.

- "Lerwick 1981–2010 averages". Met Office. Archived from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- " Jarlshof & Scatness" shetland-heritage.co.uk. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- Turner (1998) p. 18

- Melton, Nigel D. "West Voe: A Mesolithic-Neolithic Transition Site in Shetland" in Noble et al (2008) pp. 23, 33

- Melton, N. D. & Nicholson R. A. (March 2004) "The Mesolithic in the Northern Isles: the preliminary evaluation of an oyster midden at West Voe, Sumburgh, Shetland, U.K." Archived 28 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Antiquity 78 No 299.

- Fleming (2005) p. 47 quoting Clarke, P.A. (1995) Observations of Social Change in Prehistoric Orkney and Shetland based on a Study of the Types and Context of Coarse Stone Artefacts. M. Litt. thesis. University of Glasgow.

- Schei (2006) p. 10

- Nicolson (1972) pp. 33–35

- Kirk, William "Prehistoric Scotland: The Regional Dimension" in Clapperton (1983) p. 106

- Armit (2003) pp. 24–26

- Hunter (2000) pp. 44, 49

- "From Chatham to Chester and Lincoln to the Lake District — 38 UK places put themselves forward for World Heritage status" (7 July 2010) Department for Culture, Media and Sport. Retrieved 7 March 2011

- "Sites make Unesco world heritage status bid shortlist" (22 March 2011) BBC Scotland. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- Graham-Campbell (1999) p. 38

- Schei (2006) pp. 11-12

- Goodacre, S. et al (2005) "Genetic evidence for a family-based Scandinavian settlement of Shetland and Orkney during the Viking periods" Heredity 95, pp. 129–135. Nature.com. Retrieved 20 March 2011

- Thomson (2008) p. 24-27

- Thomson (2008) p. 24

- Thomson (2008) p. 69 quoting the Orkneyinga Saga chapter 12.

- Crawford, Barbara E. "Orkney in the Middle Ages" in Omand (2003) p. 64

- Schei (2006) p. 13

- Nicolson (1972) p. 43

- Hunter (2000) pp. 106-111

- Barrett (2008) p. 411

- "Agreement between Magnus IV and Alexander III, 1266" Manx Society IV, VII & IX. isleofman.com. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- Crawford, Barbara E. "Orkney in the Middle Ages" in Omand (2003) pp. 72–73

- Nicolson (1972) p. 44

- "Håkon 6 Magnusson". Om Store Norske Leksikon. (Norwegian). Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- "Diplom fra Shetland datert 24.november 1509" Archived 5 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Bergen University. (Norwegian). Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- "Norsken som døde". Universitas, Norsken som døde. (Norwegian.) Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- Nicolson (1972) p. 45

- Thomson (2008) p. 204

- Schei (2006) pp. 14–16

- Nicolson (1972) pp. 56-57

- "History". visit.shetland.org. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- "Craigie". www.electricscotland.com.

- Ursula Smith" Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Shetlopedia. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- Schei (2006) pp. 16–17, 57

- "A History of Shetland" Visit.Shetland.org. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- Hutton, Guthrie (2009) Old Shetland. Catrine, Ayrshire. Stenlake Publishing. ISBN 9781840334555 p. 3

- "Annual Statistics". www.scottishherringhistory.uk.

- "The Shetland Bus" Archived 23 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine scotsatwar.org.uk. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- Nicolson (1972) pp. 91, 94–95

- "Shetlands-Larsen — Statue/monument" Archived 29 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Kulturnett Hordaland. (Norwegian.) Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- Tallack, Malachy (2 April 2007) Fair Isle: Independence thinking. London. New Statesman.

- "Population of Shetland by Area based on Census" (PDF). Shetland.gov.uk. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- Shetland Islands Council (2010) pp. 16-17

- "Economy". move.shetland.org Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- "Asset Portfolio: Sullom Voe Termonal" (pdf) BP. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- Shetland Islands Council (2010) p. 13

- "Shetland's Economy". Visit.Shetland.org. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- Shetland Islands Council (2005) p. 13

- "Public Sector". move.shetland.org. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- "Financial Statements 31 March 2011." Shetland Charitable Trust. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- "Fifth Best Year in the Fund's History". Norges Bank Investment Management. 18 March 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- "Powering on with island wind plan" (19 January 2007). BBC News. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- "Shetlands storm over giant wind farm" (9 March 2008). London. The Observer. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- "PURE Energy Centre". Pure Energy Centre. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- "Unst Partnership". Development Trusts Association Scotland. Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- "Home" Shetland Sheep Society. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- "Shetland" Sheep101.info. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- Shetland Islands Council (2005) p. 25

- " Crofting FAQS" Scottish Crofting Federation. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- "Shetland News | Shetland's internet-only daily newspaper & digest". Shetnews.co.uk. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- Shetland News Archived 28 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- Hough, Andrew (2 November 2010) "Shetland Islands among best places to visit, says Lonely Planet guide". London. The Telegraph. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- "Cruise ship tourists set to almost double". 12 March 2018.

- Shetland Islands Council (2010) p. 26

- https://www.shetlandtimes.co.uk/2009/09/15/delight-as-shetlands-remarkable-rocks-recognised-with-geopark-status

- "Ferries". Shetland.gov.uk. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- Shetland Islands Council (2010) pp. 32, 35

- "2011 Timetables" Archived 7 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine NorthLink Ferries. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- "Shetland Isles tunnel plans - Tunnels & Tunnelling International". www.tunnelsonline.info.

- "Sumburgh Airport" Highlands and Islands Airports. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- Shetland Islands Council (2010) p. 32

- "Shetland Inter-Island Scheduled Service" directflight.co.uk. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- "UK Airport Statistics: 2005 - Annual" Archived 11 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine Table 10: EU and Other International Terminal Passenger Comparison with Previous Year. (pdf) CAA. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- Shetland Islands Council (2010) p. 34

- Ferguson, David M. (1988). Shipwrecks of Orkney, Shetland and the Pentland Firth. David & Charles. ISBN 9780715390573.

- "Lighthouse Library" Northern Lighthouse Board. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- Shetland Islands Council (2010) pp. 51, 54, 56

- "Map of Parishes in the Islands of Orkney and Shetland". Scotlands family.com Retrieved 19 July 2013

- Parish of Lerwick (example). The parish areas add up to 1357.1 km² only.

- "Schools in Shetland". Shetland Islands Council. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- Tickle, Louise (4 November 2014). "Shetland Islanders fight plan to force children to boarding school". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- "NAFC Marine Centre" Archived 4 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine North Atlantic Fisheries College. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- "Welcome! " Centre for Nordic Studies. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- "Spurs crowned senior football champions". Shetland Times. (1 October 2012) Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- "Area Profiles". Scotland's Census. Scottish Government. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- Schei (2006) p. 14

- "Area 3 Districts" Archived 19 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. methodist.org.uk. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- "Lerwick and Bressay Parish Church Profile" Archived 10 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. (pdf) shetland-communities.org.uk. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- "Alistair Carmichael: MP for Orkney and Shetland" alistaircarmichael.org.uk. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- "Candidates and Constituency Assessments" Archived 15 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine. alba.org.uk - "The almanac of Scottish elections and politics". Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- "The Untouchable Orkney & Shetland Isles "(1 October 2009) www.snptacticalvoting.com Retrieved 9 February 2010. Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Tavish Scott MSP" Scottish Parliament. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- Fraser, Gemma. Holyrood https://www.holyrood.com/news/view,lib-dems-win-shetland-byelection_10743.htm. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "About your councillors". Shetland Islands Council. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- Shetland Islands toy with idea of post-Brexit independence, EurActiv, 16 February 2017

- "Wir Shetland". Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- "Wir Shetland". Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- "Flag of Shetland". Flags of the World. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- Macdougall, Norman (1982). James III: a political study. J. Donald. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-85976-078-2. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

What James III had acquired from Earl William in return for this compensation was the comital rights in Orkney and Shetland. He already held a wadset of the royal rights; and to ensure his complete control, he referred the matter to parliament. On 20 February 1472 the three estates approved the annexation of Orkney and Shetland to the crown...

- Julian Richards, Vikingblod, page 236, Hermon Forlag, ISBN 82-3020-016-5

- "Welcome to Up Helly Aa". Uphellyaa.org. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- "Up Helly Aa" Visit.Shetland.org. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- "Member Profile: Shetland Islands". International Island Games Association. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- "Food and drink" Visit Shetland. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- "Velkomen!" Archived 7 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine nornlanguage.com. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- "Culture and Music" Archived 28 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Visit.Shetland.org. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- "Shetland ForWirds" shetlanddialect.org. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- "Shetland Folk Society" Archived 24 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Shetlopedia. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- "The Forty Fiddlers" Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Shetlopedia. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- Culshaw, Peter (18 June 2006) "The Tale of Thomas Fraser", The Guardian. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- "Shetland Folk Festival". Shetland Folk Festival. 21 May 2019.

- "Jarlshof" Gazetteer for Scotland. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- "Hugh MacDiarmid" Archived 6 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine Shetlopedia. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- Morgan, Gavin (19 April 2008) "Shetland author wins acclaim". Shetland News. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- "Shetland". Ann Cleeves.com. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- "Shetland". BBC. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- "Vagaland" Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Shetlopedia. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- "Shetland Writing and Writers: Stella Sutherland". Shetland Islands Council. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- "William J. (Billy) Tait". Shetland For Wirds. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- "Shetland Writing and Writers: Laureen Johnson". Shetland Islands Council. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- "Shetland Life" Archived 10 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine Shetlopedia. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- "Home" Millgaet Media. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- "The New Shetlander". Voluntary Action Shetland. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- "Life and Work: Part 3" Archived 11 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine. George Mackay Brown website. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- "A Crofter's Life in Shetland" screenonline.org.uk. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- "The Rugged Island: A Shetland Lyric" IMDb. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- "Street Closed for Fiming Television Crime Series". Shetland Times. 9 April 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- "Scottish actor Douglas Henshall on the perks of filming new BBC crime drama Shetland ... in & around Glasgow". Daily Record. Glasgow. 2 March 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- Shetland Islands Council (2010) p. 52

- Scott, W. & Palmer, R. (1987) The Flowering Plants and Ferns of the Shetland Islands. Shetland Times. Lerwick.

- Scott, W. Harvey, P., Riddington, R. & Fisher, M. (2002) Rare Plants of Shetland. Shetland Amenity Trust. Lerwick.

- "Flora" visit.shetland.org. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- Steer, Patrick (1999) "Shetland Biodiversity Audit". Shetland Amenity Trust.

- Maggs, C.A. and Hommersand, M.H. 1993. Seaweeds of the British Isles. The Natural History Museum, London. ISBN 0-11-310045-0

- Macdonald, Kenneth (16 August 2017). "Scientists discover a new flower of Shetland". BBC News. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- Simón-Porcar, Violeta I.; Silva, Jose L.; Meeus, Sofie; Higgins, James D.; Vallejo-Marín, Mario (October 2017). "Recent autopolyploidization in a naturalized population of Mimulus guttatus (Phrymaceae)". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 185 (2): 189–207. doi:10.1093/botlinnean/box052.

- SNH (2008) p. 16

- McFarlan, D., ed. (1991). The Guinness Book of Records. Enfield: Guinness Publishing. p. 35.

- "Home" Archived 26 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Nature in Shetland. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- Williamson, Kenneth (1951) "The wrens of Fair Isle". Ibis 93(4): pp. 599-601. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- "Endemic Vertebrates of Shetland" Archived 26 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Nature in Shetland. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- SNH (2008) p. 10

- Selous, Edmund (1905). – via Wikisource.

- Nicholson, R.A.; Barber, P.; Bond, J.M. (2005). "New Evidence for the Date of Introduction of the House Mouse, Mus musculus domesticus Schwartz & Schwartz, and the Field Mouse, Apodemus sylvaticus (L.) to Shetland". Environmental Archaeology. 10 (2): 143–151. doi:10.1179/env.2005.10.2.143.

- "Breed History" Shetland Pony Studbook Society. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- "Shetland Pony" Archived 18 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Equine World. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- "Home" Shetland Cattle Breeders Association. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- "Shetland Geese". feathersite.com. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- "Shetland Goose" American Livestock Breeds Conservancy. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- "Sheep Breeds — S–St". Sheep101.info. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- "Extinct Island Pig Spotted Again". BBC News Online. 17 November 2006. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

General references

- Armit, I. (2003) Towers in the North: The Brochs of Scotland, Stroud. Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-1932-3

- Ballin Smith, B. and Banks, I. (eds) (2002) In the Shadow of the Brochs, the Iron Age in Scotland. Stroud. Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-2517-X

- Barrett, James H. "The Norse in Scotland" in Brink, Stefan (ed) (2008) The Viking World. Abingdon. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-33315-6

- Clapperton, Chalmers M. (ed.) (1983) Scotland: A New Study. Newton Abbott. David & Charles.

- Gillen, Con (2003) Geology and landscapes of Scotland. Harpenden. Terra Publishing. ISBN 1-903544-09-2

- Graham-Campbell, James (1999) Cultural Atlas of the Viking World. Facts On File. ISBN 0-8160-3004-9

- Fleming, Andrew (2005) St. Kilda and the Wider World: Tales of an Iconic Island. Windgather Press ISBN 1-905119-00-3

- Gammeltoft, Peder (2010) "Shetland and Orkney Island-Names – A Dynamic Group". Northern Lights, Northern Words. Selected Papers from the FRLSU Conference, Kirkwall 2009, edited by Robert McColl Millar.

- General Register Office for Scotland (28 November 2003) Scotland's Census 2001 – Occasional Paper No 10: Statistics for Inhabited Islands. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

- Hunter, James (2000) Last of the Free: A History of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. Edinburgh. Mainstream. ISBN 1-84018-376-4

- Jones, Charles (ed.) (1997) The Edinburgh history of the Scots language. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-0754-4

- Keay, J. & Keay, J. (1994) Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland. London. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-255082-2

- Noble, Gordon; Poller, Tessa & Verrill, Lucy (2008) Scottish Odysseys: The Archaeology of Islands. Stroud. Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-4168-9

- Omand, Donald (ed.) (2003) The Orkney Book. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-254-9

- Nicolson, James R. (1972) Shetland. Newton Abbott. David & Charles.

- Sandnes, Berit (2003) From Starafjall to Starling Hill: An investigation of the formation and development of Old Norse place-names in Orkney. (pdf) Doctoral Dissertation, NTU Trondheim.

- Schei, Liv Kjørsvik (2006) The Shetland Isles. Grantown-on-Spey. Colin Baxter Photography. ISBN 978-1-84107-330-9

- Scottish Natural Heritage (2008) The Story of Hermaness National Nature Reserve. Lerwick.

- Shetland Islands Council (2005) "Shetland In Statistics 2005". (pdf) Economic Development Unit. Lerwick. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- Shetland Islands Council (2010) "Shetland in Statistics 2010" (pdf) Economic Development Unit. Lerwick. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- Thomson, William P. L. (2008) The New History of Orkney. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-84158-696-0

- Turner, Val (1998) Ancient Shetland. London. B. T. Batsford/Historic Scotland. ISBN 0-7134-8000-9

- Watson, William J. (1994) The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-323-5. First published 1926.

Further reading

- McMillan, Ron (2008). Between Weathers: Travels in 21st Century Shetland. Dingwall, Ross-shire: Sandstone Press. ISBN 978-1905207206. OCLC 220008309.

- Withrington, Donald J., ed. (1983). Shetland and the Outside World, 1469–1969. Aberdeen University Studies Series, no. 15. Oxford, UK: Published for the University of Aberdeen by Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780197141076. OCLC 8195814.

External links

| Look up Shetland Islands in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shetland Islands. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Shetland Islands. |

- Shetland at Curlie

- Shetland Islands Council

- Visit.Shetland.org

- Shetlopedia.com - The Online Shetland Encyclopedia

- HIE Area Profile - Shetland (PDF file) from Highlands and Islands Enterprise

- Shetlink - Shetland's Online Community

- National Library of Scotland: Scottish Screen Archive (selection of archive films about Shetland)