Harald Fairhair

Harald I Fairhair (Old Norse: Haraldr inn hárfagri; Norwegian: Harald hårfagre; putatively c. 850 – c. 932) is portrayed by medieval Icelandic historians as the first King of Norway. According to traditions current in Norway and Iceland in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, he reigned from c. 872 to 930. Supposedly, two of his sons, Eric Bloodaxe and Haakon the Good, succeeded Harald to become kings after his death.

| Harald Fairhair | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Harald Fairhair, in an illustration from the fourteenth-century Flateyjarbók. | |||||

| King of Norway | |||||

| Reign | putatively 872–930 | ||||

| Successor | Eric I | ||||

| Born | putatively c. 850 Rogaland | ||||

| Died | putatively c. 932 Rogaland, Norway | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | Ragnhild Eriksdotter Åsa Håkonsdotter | ||||

| Issue more | Eric Bloodaxe Haakon the Good | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Fairhair dynasty | ||||

| Father | Halfdan the Black | ||||

| Mother | Ragnhild Sigurdsdotter | ||||

| Religion | Norse religion | ||||

Most of Harald's biography remains uncertain, since the extant accounts of his life in the sagas were set down in writing around three centuries after his lifetime. Indeed, although it is possible to write a detailed account of Harald as a character in medieval Icelandic sagas (as this entry does), it is even possible to argue that there was no such historical figure at all.

His life is described in several of the Kings' sagas, none of them older than the twelfth century. Their accounts of Harald and his life differ on many points, but it is clear that in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries Harald was regarded as having unified Norway into one kingdom.

Meaning of epithet hárfagri

Old Norse hár translates straightforwardly into English as 'hair', but fagr, the adjective of which fagri is a form, is trickier to render, since it means 'fair, fine, beautiful'[1] (but without the moral associations of English fair, as opposed to unfair).[2] Although it is convenient and conventional to render hárfagri in English as 'fair-hair(ed)',[3][4] in English 'fair-haired' means 'blond', whereas the Old Norse fairly clearly means 'beautiful-haired' (in contrast to the epithet which, according to some sources, Haraldr previously bore: lúfa, '(thick) matted hair').[5][6] Accordingly, some translators prefer to render hárfagri as 'the fine-haired'[7] or 'fine-hair'[8][9] (which, however, unhelpfully implies that Haraldr's hairs were slender) or even 'handsome-hair'.[10]

Historicity

Through the nineteenth and most of the twentieth centuries, historians broadly accepted the account of Harald Fairhair given by later Icelandic sagas. However, Peter Sawyer began to cast doubt on this in 1976,[11] and the decades around 2000 saw a wave of revisionist research that suggested that Harald Fairhair did not exist, or at least not in a way resembling his appearance in sagas.[12][13][14][15][16][17] The key arguments for this are as follows:

- There is no contemporary support for the claims of later sagas about Harald Fairhair. The first king of Norway recorded in near-contemporary sources is Haraldr Gormsson (d. c. 985/986), who is claimed to be the king not only of Denmark but also Norway on the Jelling stones. The late ninth-century account of Norway provided by Ohthere to the court of Alfred the Great and the history by Adam of Bremen written in 1075 record no King of Norway for the relevant period. Although sagas have Erik Bloodaxe, who does seem partly to correspond to a historical figure, as the son of Harald Fairhair, no independent evidence supports this genealogical connection.[18] The twelfth-century William of Malmesbury does describe a Norwegian king called Haraldus visiting King Æthelstan of England (d. 939), which is consistent with later saga-traditions in which Harald Fairhair fostered a son, Hákon Aðalsteinsfóstri, on Æthelstan.[19] But William is a late source and Harald a far from uncommon name for a Scandinavian character,[20] and William does not give this Harald the epithet fairhair, whereas he does give that epithet to the later Norwegian king Haraldr Sigurðarsson.[21]

- Although Harald Fairhair appears in diverse Icelandic sagas, few if any of these are independent sources. It is plausible that all these were participating in a shared textual tradition begun by the earliest Icelandic prose account of Harald, Ari Þorgilsson's Íslendingabók. Dating from the early twelfth century, this was written over 250 years after Harald's supposed death.[20]

- The saga evidence is potentially pre-dated by two skaldic poems, Haraldskvæði[22] and Glymdrápa,[23] which have been attributed to Þorbjörn hornklofi or alternatively (in the case of the first poem) to Þjóðólfr of Hvinir, and are according to the sagas about Harald Fairhair. Although only preserved in thirteenth-century Kings' sagas, they might have been transmitted orally (as the sagas claim) from the tenth century. The first describes life at the court of a king called Harald, mentions that he took a Danish wife, and that he won a battle at Hafrsfjord. The second poem relates a series of battles won by a king called Harald. However, the information supplied in these poems is inconsistent with the tales in the sagas in which they are transmitted, and the sagas themselves often disagree on the details of his background and biography.[24] Meanwhile, the most reliable manuscripts of Haraldskvæði call the poem's honorand Haraldr Hálfdanarson rather than Haraldr hárfagri,[25] and Glymdrápa offers no epithet at all. All the poems suggest is that there was once a king called Haraldr (Hálfdanarson).[20]

- Sources from the British Isles which are independent of the Icelandic saga-tradition (and partly of each other), and are mostly earlier than the sagas, do attest to a king whose name corresponds to the Old Norse name Haraldr inn hárfagri—but they use this name of the well attested Haraldr Sigurðarson (d. 1066, often known in modern English as Harald Hardrada). These sources include manuscript D of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle ('Harold Harfagera', under the year 1066) and the related histories by Orderic Vitalis ('Harafagh', re events in 1066), John of Worcester ('Harvagra', s.aa. 1066 and 1098), and William of Malmesbury (Gesta regum Anglorum, 'Harvagre', s.a. regarding 1066); Marianus Scotus of Mainz ('Arbach', d. 1082/1083); and the Life of Gruffydd ap Cynan ('Haraldum Harfagyr', later twelfth century, though this may refer to two different kings by this name).[26][27][21][28]

Thus the Icelandic saga-tradition of Harald Fair-Hair can be seen as part of an origin myth created to explain the settlement of Iceland, perhaps in which a cognomen of Haraldr Sigurðarson was transferred to a fictitious early king of all Norway.[29][30] Sverrir Jakobsson has suggested that the idea of Iceland being settled by people fleeing an overbearing Norwegian monarch actually reflects the anxieties of Iceland in the early thirteenth century, when the island was indeed coming under Norwegian dominance. He has also suggested that the legend of Harald Fairhair developed in the twelfth century to enable Norwegian kings, who were then promoting the idea of primogeniture over the older custom of agnatic succession, to claim that their ancestors had had a right to Norway by lineal descent from the country's supposed first king.[31]

Saga descriptions

In the Saga of Harald Fairhair in Heimskringla, which is the most elaborate although not the oldest or most reliable source to the life of Harald, it is written that Harald succeeded, on the death of his father Halfdan the Black Gudrödarson, to the sovereignty of several small, and somewhat scattered kingdoms in Vestfold, which had come into his father's hands through conquest and inheritance. His protector-regent was his mother's brother Guthorm.

The unification of Norway is something of a love story. It begins with a marriage proposal that resulted in rejection and scorn from Gyda, the daughter of Eirik, king of Hordaland. She said she refused to marry Harald "before he was king over all of Norway". Harald was therefore induced to take a vow not to cut nor comb his hair until he was sole king of Norway, and when he was justified in trimming it ten years later, he exchanged the epithet "Shockhead" or "Tanglehair" (Haraldr lúfa) for the one by which he is usually known.[lower-alpha 1][32]

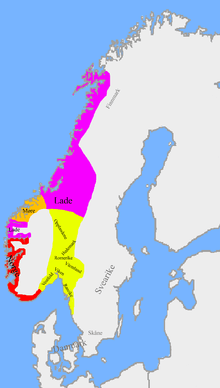

In 866, Harald made the first of a series of conquests over the many petty kingdoms which would compose all of Norway, including Värmland in Sweden, which had sworn allegiance to the Swedish saga-king Erik Eymundsson (whose historicity is not confirmed). In 872, after a great victory at Hafrsfjord near Stavanger, Harald found himself king over the whole country, ruling from his Kongsgård seats at Avaldsnes and Alrekstad. His realm was, however, threatened by dangers from without, as large numbers of his opponents had taken refuge, not only in Iceland, then recently discovered; but also in the Orkney Islands, Shetland Islands, Hebrides Islands, Faroe Islands and the northern European mainland. However, his opponents' leaving was not entirely voluntary. Many Norwegian chieftains who were wealthy and respected posed a threat to Harald; therefore, they were subjected to much harassment from Harald, prompting them to vacate the land. At last, Harald was forced to make an expedition to the West, to clear the islands and the Scottish mainland of some Vikings who tried to hide there.[lower-alpha 2][33]

The earliest narrative source which mentions Harald, the twelfth-century Íslendingabók, notes that Iceland was settled during his lifetime. Harald is thus depicted as the prime cause of the Norse settlement of Iceland and beyond. Iceland was settled by "malcontents" from Norway, who resented Harald's claim of rights of taxation over lands, which the possessors appear to have previously held in absolute ownership.

There are several accounts of large feasting mead halls constructed for important feasts when Scandinavian royalty was invited. According to a legend recorded by Snorri Sturluson, in the Heimskringla, the late 9th-century Värmlandish chieftain Áki invited both the Norwegian king Harald Fairhair and the Swedish saga-king Erik Eymundsson, but had the Norwegian king stay in the newly constructed and sumptuous one, because he was the youngest one of the kings and the one who had the greatest prospects. The older Swedish king, on the other hand, had to stay in the old feasting hall. The Swedish king was so humiliated that he killed Áki.

Later life

According to the saga sources, the latter part of Harald's reign was disturbed by the strife of his many sons. The number of sons he left varies in the different saga accounts, from 11 to 20. Twelve of his sons are named as kings, two of them over the whole country. He gave them all the royal title and assigned lands to them, which they were to govern as his representatives; but this arrangement did not put an end to the discord, which continued into the next reign. When he grew old, Harald handed over the supreme power to his favourite son Eirik Bloodaxe, whom he intended to be his successor. Eirik I ruled side-by-side with his father when Harald was 80 years old. Harald died three years later due to age in approximately 933.

Harald Harfager was commonly stated to have been buried under a mound at Haugar by the Strait of Karmsund near the church in Haugesund, an area that later would be named the town and municipal Haugesund. The area near Karmsund was the traditional burial site for several early Norwegian rulers. The national monument of Haraldshaugen was raised in 1872, to commemorate the Battle of Hafrsfjord which is traditionally dated to 872.[34][35]

Issue

While the various sagas name anywhere from 11 to 20 sons of Harald in various contexts, the contemporary skaldic poem Hákonarmál says that Harald's son Håkon would meet only "eight brothers" when arriving in Valhalla, a place for slain warriors, kings, and Germanic heroes. Only the following five names of sons can be confirmed from skaldic poems (with saga claims in parentheses), while the full number of sons remains unknown:[36]

- Eric Bloodaxe (by Ragnhild Eiriksdotter from Jutland, Denmark)

- Håkon the Good (by Tora Mosterstong from Moster, Sunnhordland, Norway)

- Ragnvald

- Bjørn (Bjørn Farmann?)

- Halvdan, possibly two by that name

According to Heimskringla

The full list of sons according to Snorri Sturluson's Heimskringla:

Children with Åsa, daughter of Håkon Grjotgardssson, Jarl av Lade:

- Guttorm Haraldsson, king of Rånrike

- Halvdan Kvite (Haraldsson), king of Trondheim

- Halvdan Svarte Haraldsson, king of Trondheim

- Sigrød Haraldsson, king of Trondheim

Children with Gyda Eiriksdottir:

- Ålov Årbot Haraldsdotter[37] (Rogaland, 875 - Giske, Møre og Romsdal, 935), married þórir Teiande, "Thore/Tore den Tause" ("the Silent") Ragnvaldsson (c. 862 - Giske, Møre og Romsdal, a. 935), Jarl av Møre, and had issue

- Rørek Haraldsson

- Sigtrygg Haraldsson

- Frode Haraldsson

- Torgils Haraldsson – identified as "Thorgest" in the (dates not correct) Irish history

Children with Svanhild, daughter of Øystein Jarl:

- Bjørn Farmann Haraldssøon, king of Vestfold and reputed great-grandfather of Norwegian king Olaf II.

- Olaf Haraldsson Geirstadalf, king of Vingulmark, later also Vestfold, and reputed father of Tryggve Olafsson, father of Norwegian king Olaf I.

- Ragnar Rykkel Haraldsson

Children with Åshild, daughter of Ring Dagsson:

- Ring Haraldsson

- Dag Haraldsson

- Gudrød Skirja Haraldsdotter

- Ingegjerd Haraldsdotter

Children with Snøfrid, daughter of Svåse the Finn:

- Halfdan Halegg Haraldsson or "Long-Leg", was executed with the Blood eagle ritual by Torf-Einarr detailed in the Orkneyinga saga and Heimskringla[38]

- Gudrød Ljome Haraldsdotter

- Ragnvald Rettilbeine Haraldsson, murdered by Eirik Blodøks on Harald's orders

- Sigurd Rise Haraldsson

Other children:

- Ingebjørg Haraldsdotter (Lade, Trondheim, c. 865 - 920), married Halvdan Jarl (c. 865 - 920), Finnmarksjarl, and had issue through an only daughter

In popular culture

In Norway

Harald Fairhair became an important figure in Norwegian nationalism in the nineteenth century, during its struggle for independence from Sweden, when he served as 'a heroic narrative character disseminating a foundation story of Norway becoming an independent nation'.[39] In particular, a national monument to Harald was erected in 1872 on Haraldshaugen, a prehistoric burial mound at the town of Haugesund then imagined to be Harald Finehair's burial place, despite opposition from left-wing politicians.

.jpg)

The claim to Harald became important to the development of the tourism industry in the town and its region:

today, King Harald Fairhair is associated with several archaeological sites where modern monuments and theme parks (obelisks, towers, sculptures, ‘reconstructions’ of ancient houses/villages) are constructed and where various commemorative practices (jubilees, rallies, festivals) are being performed. The Viking hero Harald Fairhair has become part of a vital re-enactment culture, which is evident in, among other things, a memorial park in central Haugesund with the erection of a statue of Harald Fairhair ... the performance of a Harald musical ... the building of ‘the largest’ Viking ship in the world ... the establishment of a theme park based on the Viking concept, and a historic centre where the mythology of King Harald is disseminated ... The main initiators behind these commemorative projects in the Haugesund region today are, as it was in the 1870s, local commercial entrepreneurs who are nourished by local patriotism.[40]

In 2013, commercially led archaeological excavations at Avaldsnes began with the explicit intention of developing the local heritage industry in relation to the Harald Fairhair brand, provoking a prominent debate in Norway over the appropriate handling of archaeological heritage.[41]

Elsewhere

- In the television show Vikings, a character broadly based on Harald appears in seasons 4, 5 and 6 (2016-2020) as one of the main protagonists and is portrayed by Finnish actor Peter Franzén.

- The German power-metal band Rebellion has a song dedicated to Harald Fairhair, from the album Sagas of Iceland.

- Leaves' Eyes, a symphonic metal band from Germany, wrote the album King of Kings about Harald and his conquests.

- In the game Crusader Kings II, Harald Fairhair is a playable character during the 867 start date

- Harald Fairhair is mentioned in the manga series Vinland Saga as the tyrannical unifier of Norway.

See also

Explanatory notes

- The historicity of the nickname and the anecdote around it is considered suspect by some scholars. Whaley 1993, pp. 122–123, citing Moe (1926), pp. 134–140.

- According to Peter H. Sawyer, this expedition probably never took place, cf. "Harald Fairhair and the British Isles", in "Les Vikings et leurs civilisation", ed. R. Boyer (Paris, 1976), pp. 105–09

References

- Geir T. Zoëga, A Concise Dictionary of Old Icelandic (Oxford: Clarendon, 1910), s.v. .

- Richard Cleasby and Gudbrand Vigfusson, An Icelandic-English Dictionary, 2nd edn by William A. Craigie (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1957), s.v. fagr.

- Richard Cleasby and Gudbrand Vigfusson, An Icelandic-English Dictionary, 2nd edn by William A. Craigie (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1957), s.v. hár-fagr.

- Geir T. Zoëga, A Concise Dictionary of Old Icelandic (Oxford: Clarendon, 1910), s.v. hár-fagr.

- Paul R. Peterson, 'Old Norse Nicknames' (unpublished PhD dissertation, University of Minnesota, 2015), pp. 39–40.

- Judith Jesch, 'Norse Historical Traditions and Historia Gruffud vab Kenan: Magnus Berfoettr and Haraldr Harfagri', in Gruffudd ap Cynan: A Collaborative Biography, edited by K. L. Maund (Cambridge: Boydell, 1996), pp. 117–47 (p. 139 n. 62).

- Judith Jesch, 'Norse Historical Traditions and Historia Gruffud vab Kenan: Magnus Berfoettr and Haraldr Harfagri', in Gruffudd ap Cynan: A Collaborative Biography, edited by K. L. Maund (Cambridge: Boydell, 1996), pp. 117–47 (p. 139 n. 62).

- E.g. Margaret Cormack, 'Fact and Fiction in the Icelandic Sagas, History Compass, 5/1 (2007), 201–17 (p. 203) doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2006.00363.x.

- E.g. Carl Phelpstead, 'Hair Today, Gone Tomorrow: Hair Loss, the Tonsure, and Masculinity in Medieval Iceland', Scandinavian Studies, 85 (2013), 1–19 (p. 5), doi:10.5406/scanstud.85.1.0001.

- Edith Andersen, I Am from Iceland: A Memoir (Lulu, 2010), p. 4.

- P. H. Sawyer, 'Harald Fairhair and the British Isles', in les Vikings et leur civilisation: problèmes actuelles, ed. by Régis Boyer (Paris, 1976), pp. 105–9.

- Claus Krag, 'Norge som odel i Harald Hårfagres ætt. Et møte med en gjenganger', Historisk tidskrift, 3 (1989), 288–302.

- Alexandra Pesch, Brunaǫld, haugsǫld, kirkjuǫld: Untersuchungen zu den archäologisch uberprufbaren Aussagen in der Heimskringla des Snorri Sturluson (Frankfurt am Main: Lang, 1996).

- Judith Jesch, 'Norse Historical Traditions and Historia Gruffud vab Kenan: Magnus Berfoettr and Haraldr Harfagri', in Gruffudd ap Cynan: A Collaborative Biography, edited by K. L. Maund (Cambridge: Boydell, 1996), pp. 117–47 (pp. 137–47).

- Shami Ghosh, Kings' Sagas and Norwegian History: Problems and Perspectives, The Northern World, 54 (Leiden: Brill, 2011), pp. 66–70.

- Sverrir Jakobsson, 'Yfirstéttarmenning eða þjóðmenning? Um þjóðsögur og heimildargildi í íslenskum miðaldaritum', in Úr manna minnum: Greinar um íslenskar þjóðsögur, ed. by Baldur Hafstað og Haraldur Bessason (Reykjavík, 2002), pp. 449–61.

- Sayaka Matsumoto, 'A Foundation Myth of Iceland: Reflections on the tradition of Haraldr hárfagri', 日本アイスランド学会会報 (2011), 30: 1–22.

- Clare Downham, "Eric Bloodaxe – axed? The Mystery of the Last Viking King of York", Mediaeval Scandinavia, 14 (2004), 51–77.

- Angela Marion Smith, 'King Æthelstan in the English, Continental and Scandinavian Traditions of the Tenth to the Thirteenth Centuries' (unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Leeds, 2014), pp. 255–73.

- Sverrir Jakobsson, 'Var Haraldur hárfagri bara uppspuni Snorra Sturlusonar?', Vísindavefurinn (25 September 2006).

- Sverrir Jakobsson, 'The Early Kings of Norway, the Issue of Agnatic Succession, and the Settlement of Iceland', Viator, 47 (2016), 171–88 (pp. 1–18 in open-access text, at p. 7); doi:10.1484/J.VIATOR.5.112357.

- R. D. Fulk 2012, ‘Þorbjǫrn hornklofi, Haraldskvæði (Hrafnsmál)’ in Diana Whaley (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 1: From Mythical Times to c. 1035. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 1. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 91 ff.

- Edith Marold with the assistance of Vivian Busch, Jana Krüger, Ann-Dörte Kyas and Katharina Seidel, translated from German by John Foulks 2012, ‘Þorbjǫrn hornklofi, Glymdrápa’ in Diana Whaley (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 1: From Mythical Times to c. 1035. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 1. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 73 ff.

- Krag, Claus. "Harald 1 Hårfagre". Norsk biografisk leksikon. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- R. D. Fulk 2012, ‘Þorbjǫrn hornklofi, Haraldskvæði (Hrafnsmál)’ in Diana Whaley (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 1: From Mythical Times to c. 1035. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 1. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 91 ff.

- Judith Jesch, 'Norse Historical Traditions and Historia Gruffud vab Kenan: Magnus Berfoettr and Haraldr Harfagri', in Gruffudd ap Cynan: A Collaborative Biography, edited by K. L. Maund (Cambridge: Boydell, 1996), pp. 117–47 (pp. 139–47).

- Shami Ghosh, Kings' Sagas and Norwegian History: Problems and Perspectives, The Northern World, 54 (Leiden: Brill, 2011), pp. 66–70.

- Vits Griffini Filii Conani: The Medieval Latin Life of Gruffydd ap Cynan, ed. and trans. by Paul Russell (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2005), pp. 54-57 (chs 4-5).

- Sayaka Matsumoto, 'A Foundation Myth of Iceland: Reflections on the tradition of Haraldr hárfagri', 日本アイスランド学会会報 (2011), 30: 1–22.

- Gísli Sigurðsson, 'Constructing a Past to Suit the Present: Sturla Þórðarson on Conflicts and Alliances with King Haraldr hárfagri', in Minni and Muninn: Memory in Medieval Nordic Culture, ed. by Pernille Hermann, Stephen A. Mitchell, and Agnes S. Arnórsdóttir, AS 4 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2014), pp. 175–96 doi:10.1484/M.AS-eb.1.101980.

- Sverrir Jakobsson, 'The Early Kings of Norway, the Issue of Agnatic Succession, and the Settlement of Iceland', Viator, 47 (2016), 171–88; doi:10.1484/J.VIATOR.5.112357.

- Whaley, Diana (1993), "Nicknames and Narratives in the Sagas", Arkiv för Nordisk Filologi, 108: 122–23, archived from the original on 2017-03-08, retrieved 2017-03-08

- P. H. Sawyer, "Harald Fairhair and the British Isles", in "Les Vikings et leurs civilisation", ed. R. Boyer (Paris, 1976), pp. 105–09.

- "Heimskringla, by Snorri Sturluson". Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- Heimskringla, The Chronicle of the Kings of Norway

- Krag, Claus (1995). Vikingtid og rikssamling: 800–1130. pp. 92–95. ISBN 8203220150.

- "Ålov Årbot (Haraldsdotter) (Ólöf árbót)". Det Norske Samlaget. Retrieved May 25, 2016.

- Hollander, Lee (1964). Heimskringla: History of the Kings of Norway (7th, 2009 ed.). Univ of Texas Press. p. 84. ISBN 9780292786967.

- Torgrim Sneve Guttormsen, 'Branding local heritage and popularising a remote past: The example of Haugesund in Western Norway', AP: Online Journal in Public Archaeology, 1 (2014), 45–60 (p. 47).

- Torgrim Sneve Guttormsen, 'Branding local heritage and popularising a remote past: The example of Haugesund in Western Norway', AP: Online Journal in Public Archaeology, 1 (2014), 45–60 (p. 54).

- Torgrim Sneve Guttormsen, 'Branding local heritage and popularising a remote past: The example of Haugesund in Western Norway', AP: Online Journal in Public Archaeology, 1 (2014), 45–60 (pp. 54–55).

Sources

- Viking Empires by Angelo Forte, Richard Oram and Frederik Pedersen (Cambridge University Press. June 2005)

- The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings Peter Sawyer, Editor (Oxford University Press, September 2001)

- Jakobsson, Sverrir, "Erindringen om en mægtig personlighed : den norsk-islandske historiske tradisjon om Harald Hårfagre i et kildekristisk perspektiv]," Historisk tidsskrift, 81 (2002), 213–30.

- Raffensperger, Christian, "Shared (Hi)Stories: Vladimir of Rus' and Harald Fairhair of Norway," The Russian Review, 68,4 (2009), 569–582.

Harald Fairhair Born: c. 850 Died: c. 933 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| New title | King of Norway 872–930 |

Succeeded by Eric I |