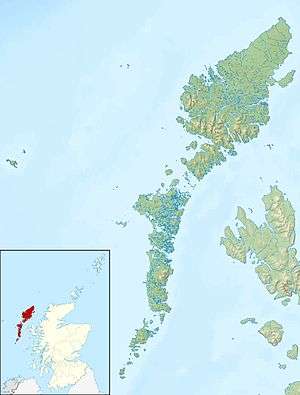

South Uist

South Uist (Scottish Gaelic: Uibhist a Deas, [ˈɯ.ɪʃtʲ ə ˈtʲes̪] (![]()

| Gaelic name | Uibhist a Deas |

|---|---|

| Meaning of name | Pre-Gaelic and unknown[1] |

| |

| |

| Location | |

South Uist South Uist shown within the Outer Hebrides | |

| OS grid reference | NF786343 |

| Coordinates | 57.2667°N 7.3167°W |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Uist & Barra[2] |

| Area | 32,026 hectares (124 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 9 [3] |

| Highest elevation | Beinn Mhòr 620 metres (2,030 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | Na h-Eileanan Siar |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 1,754[4] |

| Population rank | 9 [3] |

| Population density | 5.5 people/km2[4][5] |

| Largest settlement | Lochboisdale |

| References | [5][6][7][8] |

The island is home to a nature reserve and a number of sites of archaeological interest, including the only location in the British Isles where prehistoric mummies have been found. In the northwest, there is a missile testing range. In 2006 South Uist, together with neighbouring Benbecula and Eriskay, was involved in Scotland's biggest-ever community land buyout.

Geology

In common with the rest of the Western Isles, South Uist is formed from the oldest rocks in Britain, Lewisian gneiss brought to the surface by old tectonic movements. They bear the scars of the last glaciation which has exposed many of them. The rocks had high-grade regional metamorphism around 2,900 million years ago: in the Archaean eon. Some show granulite facies metamorphism, but most have slightly cooler amphibolite facies. A number of metabasic bodies and metasediments occur locally in the gneiss.[10]

On the east side of the island between Lochboisdale and Ornish – part of the Outer Hebrides Thrust Zone – is the Corodale gneiss, dominated by garnet-pyroxene rock. A narrow zone of pseudotachylyte occurs along its western margin with the regular gneiss. The Usinish peninsula is formed from ‘mashed gneiss’, within which the banding has mainly been destroyed. Between these two gneisses is a band of mylonite (as offshore on Stuley). Mashed gneiss occurs again in the extreme southeast. Small occurrences of Archaean granites are found in the centre of the island.[10][11]

The island is traversed by many normal faults: E to W, to NNW to SSE, many being NW to SE. Numerous NW to SE dykes cut through the island: quartz-dolerite, camptonite and monchiquite dykes of Permo-Carboniferous age and later Palaeogene tholeiitic dykes. More recent geological deposits include blown sand along the northern and western coasts and peat inland along with some (glacial) till.[12]

Geography

The west is machair (fertile low-lying coastal plain) with a continuous sandy beach, whilst the east coast is mountainous with the peaks of Beinn Mhòr (Gèideabhal) at 620 metres (2,030 ft) and Hecla at 606 metres (1,988 ft).

The main village on the island is Lochboisdale (Loch Baghasdail), from which ferries sail to Oban on the mainland and to Castlebay (Bàgh a' Chaisteil) on Barra. The island is linked to Eriskay and Benbecula by causeways. Smaller settlements include Daliburgh (Dalabrog), Howmore (Tobha Mòr) and Ludag (An Lùdag).

Climate

South Uist has an oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb).

| Climate data for South Uist Range (4 m or 13 ft asl, averages 1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.7 (45.9) |

7.2 (45.0) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.2 (50.4) |

12.9 (55.2) |

14.6 (58.3) |

16.1 (61.0) |

16.1 (61.0) |

14.9 (58.8) |

12.2 (54.0) |

9.8 (49.6) |

8.1 (46.6) |

11.5 (52.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.1 (37.6) |

3.0 (37.4) |

3.8 (38.8) |

5.1 (41.2) |

7.4 (45.3) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.4 (52.5) |

11.5 (52.7) |

10.4 (50.7) |

7.8 (46.0) |

5.3 (41.5) |

3.6 (38.5) |

6.8 (44.3) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 140.1 (5.52) |

94.9 (3.74) |

104.3 (4.11) |

67.3 (2.65) |

58.3 (2.30) |

61.7 (2.43) |

77.7 (3.06) |

100.5 (3.96) |

105.4 (4.15) |

136.2 (5.36) |

128.9 (5.07) |

118.4 (4.66) |

1,193.7 (47.01) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1 mm) | 20.6 | 16.4 | 19.8 | 13.2 | 11.6 | 13.4 | 14.0 | 16.9 | 15.4 | 20.8 | 21.3 | 19.4 | 202.8 |

| Source: Met Office[13] | |||||||||||||

Etymology

Mac an Tàilleir (2003) suggests that the derivation of Uist may be "corn island".[14] However, whilst noting that the vist ending would have been familiar to speakers of Old Norse as meaning "dwelling", Gammeltoft (2007) says that the word is "of non-Gaelic origin" and that it reveals itself as one of a number of "foreign place-names having undergone adaptation in Old Norse". In contrast, Clancy (2018) has argued that Ívist itself is an Old Norse calque on an earlier Gaelic name, *Ibuid or Ibdaig, which corresponds to Ptolemy’s Eboudai.[15]

History

Early history

South Uist was clearly home to a thriving Neolithic community. The island is covered in several neolithic remains, such as burial cairns,[note 1] and a small number of standing stones, of which the largest—standing 17 feet (5.2 m) tall—is in the centre of the island, at the northern edge of Beinn A' Charra. Occupation continued into the Chalcolithic, as evidenced by a number of Beaker finds throughout the island.

Later in the Bronze Age, a man was mummified,[note 2] and placed on display at Cladh Hallan, parts occasionally being replaced over the centuries; he was joined by a woman three hundred years later. Together they are the only known prehistoric mummies in the British Isles.[16] Towards the end of the Bronze Age, the mummies were buried,[note 3] and a row of roundhouses built on top of them.

Cladh Hallan was not abandoned until the late Iron Age. At around that time, in the 2nd century BC, a broch was built at Dun Vulan; archeological investigation suggests the inhabitants often ate pork. After the 2nd century AD, the Dun Vulan broch was converted into a three-roomed house. At a similar time, a wheelhouse was constructed at Kilpheder; within a cupboard (in the wheelhouse) was found an enameled bronze brooch, of a style fashionable in the Roman Britain of 150 AD.[note 5]

Kingdom of the Isles

In the 9th century, Vikings invaded South Uist, along with the rest of the Hebrides, and the gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata to the south, and established the Kingdom of the Isles throughout these lands. A short Ogham inscription has been found in Bornish, inscribed on a piece of animal bone, dating from this era;[17] it is thought that the Vikings used it as a gaming token, or perhaps for sortilege.[17]

Following Norwegian unification, the Kingdom of the Isles became a crown dependency of the Norwegian king; to the Norwegians it was Suðreyjar (meaning southern isles). Malcolm III of Scotland acknowledged in writing that Suðreyjar was not Scottish, and king Edgar quitclaimed any residual doubts. At Kilpheder, the roundhouses were abandoned in favour of Norse longhouses;[note 6] at Bornish, a few miles to the north, a more substantial Norse settlement was built.[note 7] As indicated by archaeological finds, residents had access to a wide trading network, stretching throughout the Norwegian empire, as well as adjacent lands like Ireland.

However, in the mid-12th century, Somerled, a Norse-Gael of uncertain origin, launched a coup, which made Suðreyjar entirely independent. Following his death, Norwegian authority was nominally restored, but in practice the kingdom was divided between Somerled's heirs (Clann Somhairle), and the dynasty that Somerled had deposed (the Crovan dynasty). The MacRory, a branch of Somerled's heirs, ruled Uist, as well as Barra, Eigg, Rùm, the Rough Bounds, Bute, Arran and northern Jura.[18][19][20][21][22][note 8] A small monastery was established at Howmore.[note 9]

Lordships

In the 13th century, despite Edgar's quitclaim, Scottish forces attempted to conquer parts of Suðreyjar, culminating in the indecisive Battle of Largs. In 1266, the matter was settled by the Treaty of Perth, which transferred the whole of Suðreyjar to Scotland, in exchange for a very large sum of money.[note 10] The Treaty expressly preserved the status of the rulers of Suðreyjar; the MacRory lands, excepting Bute, Arran, and Jura, became the Lordship of Garmoran, a quasi-independent crown dependency, rather than an intrinsic part of Scotland. Following this, the Norse longhouses were gradually abandoned, in favour of new Blackhouses[note 11] and a new parish church was built at Howmore for South Uist.[note 12]

At the turn of the century, William I had created the position of Sheriff of Inverness, to be responsible for the Scottish highlands, which theoretically now extended to Garmoran.[24][25] In 1293, however, king John Balliol established the Sheriffdom of Skye, which included the Outer Hebrides. Nevertheless, following his usurpation, the Skye sheriffdom ceased to be mentioned,[note 13] and the Garmoran lordship (including Uist) was confirmed to the MacRory leader. In 1343, King David II issued a further charter for this to the latter's son.[26]

Just three years later[note 14] the sole surviving MacRory heir was Amy of Garmoran. The southern parts of the Kingdom of the Isles had become the Lordship of the Isles, ruled by the MacDonalds (another group of Somerled's descendants). Amy married the MacDonald leader, John of Islay, but a decade later he divorced her, and married the king's niece instead (in return for a substantial dowry). As part of the divorce, John deprived his eldest son, Ranald, of the ability to inherit the Lordship of the Isles, in favour of a son by his new wife. As compensation, John granted Lordship of Uist to Ranald's younger brother Godfrey, while making Ranald Lord of the remainder of Garmoran.

However, on Ranald's death, disputes between Godfrey and his nephews (the elder of which founded Clan Ranald) lead to an enormous amount of violent feuding. In 1427, frustrated with the level of violence in the highlands, King James I demanded that highland leaders should attend a meeting at Inverness. On arrival, many of the leaders were seized and imprisoned; Alexander MacGorrie, son of Godfrey, was considered to be one of the two most reprehensible, and after a quick show trial, was immediately executed.[27] King James declared the Lordship of Uist forfeit.

Fracture

Following the forfeiture, and in that same year, the Lord of the Isles granted Lairdship of the southern third of South Uist (traditionally called Lochboisdale[note 15]), together with Barra, to Giolla Adhamhnáin mac Néill, leader of the MacNeils. At around this time Calvay Castle was built, guarding Lochboisdale.

The remainder of South Uist remained with the Scottish crown until 1469, when James III granted Lairdship of it to John of Ross, the Lord of the Isles; in turn, John passed it to his own half-brother, Hugh of Sleat (the grant to Hugh was later confirmed by the king—James IV—in a 1493 charter). Hugh died a few years later, in 1498, and for reasons that are not remotely clear, his son—John of Sleat—immediately resigned, transferring all authority to the king.

On 3 August that same year, king James IV awarded the central third of South Uist (traditionally known as Kilpheder[note 16]), by charter to Ranald Bane, leader of Clan Ranald.[28] Two days later,[note 17] the king gave Ranald Bane a charter for the northern third (traditionally known as Skirhough[note 18]) as well.[28] Ranald Bane, or his heirs, built Casteal Bheagram, on Loch an Eilean in Skirhough, as their local stronghold.[note 19]

John Moidartach and his sons

Some time after Ranald Bane's nephew, John Moidartach,[note 20] succeeded as laird, he fell out of favour with King James V.[note 21] By 1538, James had transferred lairdship of Kilpheder to John's younger half-brother, Farquhar;[note 22][29] the king gave him Skirhough shortly afterwards.[30] In 1563, Farquhar sold his portion of South Uist to a distant relation, James MacDonald (heir of the second son of John of Islay);[note 23][31] that same year, Mary, Queen of Scots, issued a charter confirming James MacDonald as laird of these lands.[32]

In the following year, Farquhar was murdered by John Moidartach's sons.[33] The year after that,[note 24] as opponents of the Scottish reformation, Moidartach and his family took the side of the Queen during the Chaseabout Raid, and were consequently back in royal favour; the Queen prohibited them from being punished for Farquhar's murder.[33] By the last decades of the century, John Moidartach had obtained a practical hold on Farquhar's former lands, though seemingly as a tenant of James MacDonald's heirs. In 1584 John died, and was buried at Howmore; a decorated stone from the site (the Clanranald Stone) is thought to have been his headstone.[note 25]

In 1596, concerned by the active involvement of highland leaders in Irish rebellions against Queen Elizabeth of England, king James VI of Scotland (Elizabeth's heir) demanded that they send well-armed men, as well as attending themselves, to meet him at Dumbarton on 1 August, and produce the charters for their land. As neither John Moidartach's heirs, nor those of James MacDonald, did so, Skirhough and Kilpheder became forfeit, by the corresponding Act of Parliament. Consequently, the king awarded them to Donald Gorm Mor, the heir of Hugh of Sleat, as a reward;[34] he had been one of the few highland leaders who obeyed the king's summons.[35] Donald Gorm Mor subinfeudated Skirhough and Kilpheder back to Clan Ranald, for £46 per annum.

Reunification

The leader of the MacNeils did not submit to the 1609 Statutes of Iona. Using this as justification, Clan Ranald drove the MacNeils out of Lochboisdale, and were subsequently awarded a charter for it, in 1610.[36] In 1622, Donald Gorm Mor's successor, Donald Gorm Og,[note 26] is found requesting that the Privy Council physically punish the Clan Ranald leadership for not removing their families and tenants from Skirhough;[37] presumably they hadn't been paying the rent.[38] By way of settlement of the dispute,[note 27] Donald Gorm Og was granted lairdship over Lochboisdale as well;[38] thus Donald Gorm Og became laird of the whole of South Uist, while Clan Ranald held it as his feudal vassals.

In 1633, Donald Gorm Og decided to simply sell lairdship of South Uist to the Earl of Argyll;[note 28] in January 1634, this arrangement was confirmed by a crown charter.[39] In 1661, as a leading opponent of king Charles I, the Earl's son—the Marquess of Argyll—was convicted of high treason, and his lands became forfeit. Thus, in 1673, it was the king demanding that Clan Ranald pay their outstanding rent for South Uist.[40]

Debt, poverty and loss

In 1701, Allen MacDonald, the leader of Clan Ranald, built Ormaclete Castle as his new main residence in UIst. In 1715, some venison caught fire in the kitchen, which lead to the whole castle burning down. Like many of the MacDonald leaders, Allen was a supporter of the Jacobite rebellion, and a few days later, at the Battle of Sheriffmuir, was himself killed. After this, the Clan Ranald leadership moved their main home in Uist back to Benbecula.

During the Jacobite rising of 1745, Ranald MacDonald, the son of the Clan Ranald leader,[note 29] amassed large amounts of debt by funding the Jacobite army.[note 30] In the following year, Bonnie Prince Charlie was able to hide at Calvay Castle, after fleeing from the Battle of Culloden, until he was able to escape with the aid of Flora MacDonald. Though an act of attainder (and forfeit) was subsequently passed against Ranald, it had no effect, due to accidentally naming him as Donald MacDonald.

Ranald's debts proved burdensome for his family, but his grandson, Ranald George MacDonald, was able to keep them at bay thanks to the Napoleonic Wars; the wars had restricted the supply of certain minerals, turning the production of soda ash by burning kelp into a highly profitable activity. Kelp harvesting (and burning) became one of the principle economic activities of the population of South Uist,[41] but when the wars ended, competition from imported barilla resulted in the kelp price collapsing.[42] In 1837, facing bankruptcy,[42] Ranald sold South Uist to Lt. Colonel John Gordon of Cluny.

Already accustomed to treating people as slaves, and seeing the financial advantages to livestock farming, Gordon was ruthless, evicting the population with short notice. On 11 August 1851, he demanded that everyone in South Uist attend a public meeting at Lochboisdale; according to an eyewitness,[note 31] he dragged the attendees from the meeting, sometimes in handcuffs, and threw then onto waiting ships, like cattle.[43] Having cleared much of the land, he replaced the population with flocks of Blackface sheep, bringing in lowland farmers to care for them. The former population largely moved to Canada; the remaining populace of South Uist represented less than half of the 1841 total.[note 32][44]

Later history

Lochboisdale became a major herring port later in the 19th century. In 1889, counties were formally created in Scotland, on shrieval boundaries, by a dedicated Local Government Act; South Uist therefore became part of the new county of Inverness. Following late 20th-century reforms, South Uist became part of the Highland Region.

The population level remained steady after the 19th-century clearances (in 2004 it was 2,285[44]). Following a series of different landowners, South Uist has been owned by South Uist Estates Ltd since 1960. In 2006, the local community bought all of the company's shares, via the special purpose vehicle Sealladh na Beinne Mòire, which now serves as the holding company, with the trading name now being Stòras Uibhist.[45] [46]

Economy

Tourism is important to the island's economy and attractions include the Kildonan Museum, housing the 16th-century Clanranald Stone, and the ruins of the house where Flora MacDonald was born.

South Uist is home to the Askernish Golf Course.[47] The oldest course in the Outer Hebrides, Askernish was designed by Old Tom Morris, who also worked on the Old Course at St Andrews. Morris was commissioned by Lady Gordon Cathcart in 1891.[48] The Askernish course existed intact until the 1930s, but was partly destroyed to make way for an aircraft runway, then abandoned, and ultimately lost. Its identity remained hidden for many years before its apparent discovery, a claim disputed by some locals.[49][50][51] Restoration of the course to Morris's original design was held up by disagreements with local crofters,[52][53] but after legal challenges were resolved in the courts, the course opened in August 2008.

The popular summer music school, Ceòlas,[54] takes place every year from the first Sunday of July in Daliburgh School on the island. In 2019, it was estimated that the school contributed around £210,000 to the local economy.[55] It is then followed by the local children's summer school, Fèis Tir a'Mhurain.

After a protracted campaign South Uist residents took control of the island on 30 November 2006 in Scotland's biggest community land buyout to date. The previous landowners, a sporting syndicate, sold the assets of the 92,000-acre (370 km2) estate for £4.5 million[56] to a Community Company known as Stòras Uibhist, which was set up to purchase the land and to manage it.[57][58] The buyout resulted in most of South Uist, and neighbouring Benbecula, and all of Eriskay coming under community control.[59]

The proposal for community ownership received the overwhelming support of the people of the islands, who "look forward to regenerating the local economy, reversing decline and depopulation, and reducing dependency, while remaining aware of the environmental needs, culture and history of the islands". The company claims its name—Stòras Uibhist (meaning Uist Resource)—symbolises hope for the future wealth and prosperity of the islands.

The SEARCH project (Sheffield Environmental and Archaeological Research Campaign in the Hebrides) on South Uist has been developing a long-term perspective on changes in settlement and house form from the Bronze Age to the 19th century.

Missile testing

In the north west of the island at (57°20′N 07°20′W), a missile testing range was built in 1957–58 to launch the Corporal missile, Britain and America's first guided nuclear weapon. This development went ahead despite significant protests, some locals expressing concern that the Scottish Gaelic language would not survive the influx of English-speaking Army personnel. The British Government claimed that there was an 'overriding national interest' in establishing a training range for their newly purchased Corporal, a weapon that was to be at the front line of Cold War defence. The Corporal missile was tested from 1959 to 1963, before giving way to Sergeant and Lance tactical nuclear missiles. The 'rocket range' as it is known locally has also been used to test high-altitude research rockets, Skua and Petrel. Local opposition to the range inspired the 1957 novel Rockets Galore by Compton Mackenzie.

The Deep Sea Range is still owned by the MoD operated by QinetiQ as a testing facility for missile systems such as the surface-to-air Rapier missile and unmanned aerial vehicles.[60] In 2009 the MOD announced that it was considering running down its missile testing ranges in the Western Isles,[61] with potentially serious consequences for the local economy.

Wildlife and conservation

.jpg)

The west coast of South Uist is home to the most extensive cultivated machair system in Scotland,[62] which is protected as protected a both a Special Area of Conservation and a Special Protection Area under the Natura 2000 programme.[63][64] Over 200 species of flowering plants have been recorded on the reserve, some of which are nationally scarce. South Uist is considered the best place in the UK for the aquatic plant Slender Naiad (Najas flexilis),[65] which is a European Protected Species. Nationally important populations of breeding waders are also present, including redshank, dunlin, lapwing and ringed plover. The island is also home to greylag geese on the lochs, and in summer corncrakes on the machair. Otters and hen harriers are also seen.[63][64]

Loch Druidibeg in the north of the island was formerly (until 2012) a national nature reserve owned and managed by Scottish Natural Heritage.[66] The area, which is now protected as a Site of Special Scientific Interest, covers 1,675 hectares of machair, bog, freshwater lochs, estuary, heather moorland and hill.[67][68] Ownership of the SSSI was transferred from SNH to the local community-owned company Stòras Uibhist.[69]

An area of the south west coast of the island is designated as the South Uist Machair National Scenic Area,[70] one of 40 such areas in Scotland which are defined so as to identify areas of exceptional scenery and ensure its protection from inappropriate development.[71] The designated area covers 13,314 ha in total, of which 6,289 ha is on land, with a further 7,025 ha being marine (i.e. below low tide level).[72]

There has been considerable controversy over hedgehogs on South Uist. The animals are not native to the islands, having been introduced in the 1970s to reduce garden pests. It is claimed that they pose a threat to the eggs of ground-nesting wading birds on the island. In 2003 the Uist Wader Project—headed by Scottish Natural Heritage—began a cull of hedgehogs in the area. Following a campaign and concerns over animal welfare, this cull was called off in 2007; instead, hedgehogs are being captured and moved to mainland Scotland.[73][74][75]

Along with the island's situation on the North Atlantic Ocean, its machair is considered to be one of the most vulnerable coasts in Scotland due to relative sea level rise and the potential effects of climate change.[76] Specifically, research[77] has shown that the most vulnerable areas include Ìochdar, Stoneybridge, Cille Pheadair, and Orasay.

Gaelic

At the 2011 Census it was found that 1,888 Gaelic speakers live on South Uist and Benbecula, this being 60% of the two islands' population.[78] 'Na Meadhoinean', Middle District in South Uist, is the strongest Gaelic-speaking community in the world, at 82%.

Notable residents

- Angus Peter Campbell (born 1952) poet, novelist, journalist, broadcaster and actor.

- Kathleen MacInnes (born 1969), singer, TV presenter and actress

- Danny Alexander (born 1972), Liberal Democrat Member of Parliament; lived at West Geirnish on South Uist for three years as a child[79]

- Flora MacDonald (1722–1790), born at Milton; known for her help of Bonnie Prince Charlie

- Angus McPhee (1916–1997), born at Iochdar; outsider artist

- Margaret Fay Shaw (1903–2004), American photographer and folklorist

See also

- List of islands of Scotland

- Bun Sruth, a loch in the southeast

- Easaval, a hill in the south

- Iochdar, a hamlet on the west coast

- Kilaulay, a township on the northwest coast

- Ushenish, a headland on the east coast

- Scottish island names

Footnotes

- By the early 21st century, cairns had been identified at Sig More, Glac Hukarvat, Reineval, Barp Frobost, Loch a'Bharp and Leaval. A variant style was found at Dun Trossary, which is a long horned cairn. Most are in poor condition, but the cairn at Reineval is exceptionally well-preserved.

- ~1600 BC

- in 1120BC, for reasons which are now unknown

- It is the first floor which is exposed; the ground floor lies buried beneath the surface, and the entrance passage remains intact.

- A photograph can be found here, by entering the search term "000-100-039-059-C"

- the substantial remains of which were largely destroyed by a storm in the early 21st century

- containing at least 20 houses; the largest Norse settlement yet found in modern Scotland

- Muck and Canna were ruled by the Bishop of the Isles and Abbot of Iona, respectively

- St. Dermot's Chapel and parts of the Clan Ranald chapel date from this period

- 4,000 marks

- in which the space was shared with livestock,[23]

- Now called the big church (Teampall Mòr in Gaelic)

- in surviving records, at least

- 1346

- , after Lochboisdale, which forms its northern boundary

- after its main settlement, Kilpheder

- 5 August

- after its main settlement, Howmore; Sgire is Gaelic for district

- Ranald's grandchildren, and their heirs, used Borve Castle, on Benbecula, as their main residence in Uist; Caisteal Bheagram, as a small tower, was more useful merely as a refuge, and vantage point.

- Moidartach refers to Moidart

- Surviving records do not explain why.

- Though they shared the same father, Farquhar's mother was Marion MacIntosh, while the name of John's mother was Dorothy (her surname is unknown).

- for 2,000 marks

- 1565

- Following the theft of the stone, in the 1990s, it is now located at the Kildonan museum.

- Og means the younger

- agreed at the Chanonry of Ross

- for 26,921 marks, 10 shillings, and 8 pence

- who was also called Ranald

- his father, by contrast, was unwilling to actively support the campaign

- Catherine MacPhee

- which was 5093

References

- Gammeltoft, Peder "Scandinavian Naming-Systems in the Hebrides—A Way of Understanding how the Scandinavians were in Contact with Gaels and Picts?" in Ballin Smith et al (2007) p. 487

- The correct term for the island group is Uist and Barra, as evidenced by the name of the local hospital. https://www.wihb.scot.nhs.uk/ospadal-uibhist-agus-bharraigh

- Area and population ranks: there are c. 300 islands over 20 ha in extent and 93 permanently inhabited islands were listed in the 2011 census.

- National Records of Scotland (15 August 2013). "Appendix 2: Population and households on Scotland's Inhabited Islands" (PDF). Statistical Bulletin: 2011 Census: First Results on Population and Household Estimates for Scotland Release 1C (Part Two) (PDF) (Report). SG/2013/126. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

- The Chronicles of Mann. Manx Society. Vol XXII, Retrieved 4 July 2007.

- Germanic Lexicon Project Retrieved 4 July 2007.

- Ordnance Survey. OS Maps Online (Map). 1:25,000. Leisure.

- General Register Office for Scotland (28 November 2003) Scotland's Census 2001 – Occasional Paper No 10: Statistics for Inhabited Islands. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- "Uist and Barra (North)". BGS large map images. British Geological Survey. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- "Uist and Barra (South)". BGS large map images. British Geological Survey. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- "Onshore Geoindex". British Geological Survey. British Geological Survey. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- "South Uist Range (Na h-Eileanan Siar) UK climate averages". Met Office. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 116

- Clancy, Thomas Owen (2018). "Hebridean connections: in Ibdone insula, Ibdaig, Eboudai, Uist" (PDF). The Journal of Scottish Name Studies. 12: 27–40. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- BBC - History - The Mummies of Cladh Hallan

- An Ogham-Inscribed Plaque from Bornais, South Uist, Katherine Forsyth in West over Sea: Studies in Scandinavian Sea-Borne Expansion and Settlement Before 1300, edited by Gareth Williams, 2007, Koninklijke Brill, p. 471-472

- Kingship and Unity, Scotland 1000-1306, G. W. S. Barrow, Edinburgh University Press, 1981

- Galloglas: Hebridean and West Highland Mercenary Warrior Kindreds in Medieval Ireland, John Marsden, 2003

- Lismore: The Great Garden, Robert Hay, 2009, Birlinn Ltd

- Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 90 (1956-1957), A.A.M. Duncan, A.L Brown, pages 204-205

- The Kingdom of the Isles: Scotland's Western Seaboard, R. A. McDonald, 1997, Tuckwell Press

- Smith, H., Marshall, P. and Parker Pearson, M. 2001. Reconstructing house activity areas pp. 249-270. In Albarella, U (ed) Environmental Archaeology: Meaning and Purpose. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Dickinson W.C., The Sheriff Court Book of Fife, Scottish History Society, Third Series, Vol. XII (Edinburgh 1928), pp. 357–360

- The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707, K.M. Brown et al eds (St Andrews, 2007-2017), 15 July 1476

- Regesta Regum Scottorum VI ed. Bruce Webster (Edinburgh 1982) no. 73.

- Gregory, Donald (1836), History of the Western Highlands and Isles of Scotland, from A.D. 1493 to A.D. 1625, with a brief introductory sketch, from A.D. 80 to A.D. 1493, Edinburgh, W. Tait, retrieved 11 May 2012, p. 65

- Angus & Archibald Macdonald. The Clan Donald volume 2, The Northern Counties Publishing Company Ltd, 1900, p. 238

- Register of the Privy Seal of Scotland, edited by M. Livingstone, 1908, HM General Register House, volume II, entry 441

- Register of the Privy Seal of Scotland, edited by M. Livingstone, 1908, HM General Register House, volume II, entry 592

- Clan Donald, Donald J MacDonald, MacDonald Publishers (of Loanhead, Midlothian), 1978, p.298

- Register of the Great Seal of Scotland, edited by Maitland Thomson, 1912, HM General Register House, volume IV, entry 335

- Clan Donald, Donald J MacDonald, MacDonald Publishers (of Loanhead, Midlothian), 1978, p.301

- Register of the Great Seal of Scotland, edited by Maitland Thomson, 1912, HM General Register House, volume VI, entry 161

- Clan Donald, Donald J MacDonald, MacDonald Publishers (of Loanhead, Midlothian), 1978, p.309

- Register of the Great Seal of Scotland, edited by Maitland Thomson, 1912, HM General Register House, volume VII, entry 129

- Register of the Privy Council of Scotland, edited by I Hill-Burton, 1877, HM General Register House, volume XIII, 741-742

- Angus & Archibald Macdonald. The Clan Donald volume 2, The Northern Counties Publishing Company Ltd, 1900, p. 320-321

- Angus & Archibald Macdonald. The Clan Donald volume 2, The Northern Counties Publishing Company Ltd, 1900, p. 324

- Angus & Archibald Macdonald. The Clan Donald volume 2, The Northern Counties Publishing Company Ltd, 1900, p. 339

- Innes, Bill (2006). Old South Uist. Catrine, Ayrshire: Stenlake Publishing. p. 3,4. ISBN 9781840333817.

- Innes, Bill (2006). Old South Uist. pp. 3, 4.

- The Jaws of Sheep: The 1851 Hebridean Clearances of Gordon of Cluny, James A. Stewart, in Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium, 1999

- South Uist:Archaeology and History of a Hebridean Island. Pearson, Shaples, Symonds. 2004. ISBN 978-0-7524-2905-2

- "About Us". Stòras Uibhist. 2013. Retrieved 2018-06-14.

- "Who owns Scotland?". The Scotsman.

- Askernish Golf Course

- Owen, David (28 June 2009). "The missing links". The Observer. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- cybergolf.com re Askernish course. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 16 June 2007.

- "Crofters deny Old Tom claim". BBC News. 15 June 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-18.

- Forgan, Duncan (28 July 2007). "Island pins hopes on past links". The Scotsman. Edinburgh.

- Storas Uibhist press release

- David Owen (April 20, 2009). "The Ghost Course". New Yorker.

- Ceòlas

- https://www.pressreader.com/uk/the-oban-times/20190725/282016148922811

- "Land buyout reality for islanders". BBC News. 30 November 2006. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- Stòras Uibhist

- Islanders pay £4.5m to be rid of feudal lairds The Independent newspaper. (1 December 2006) Retrieved 29 July 2007.

- The quiet revolution. (19 January 2007) Broadford. West Highland Free Press.

- QinetiQ: Hebrides Operations

- Ross, John (31 July 2009). "In 1930, the last islanders left. Now St Kilda Day celebrates their legacy". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Retrieved 2009-08-10.

- "South Uist Machair SAC". Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Retrieved 2018-06-11.

- "South Uist Machair and Lochs SPA". Scottish Natural Heritage. 2018-06-06. Retrieved 2018-06-11.

- "South Uist Machair SAC". Scottish Natural Heritage. 2018-06-06. Retrieved 2018-06-11.

- JNCC Slender Naiad report Retrieved 29 July 2007.

- "Scottish National Heritage" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-14. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- "Loch Druidibeg SSSI". Scottish Natural Heritage. 2018-06-06. Retrieved 2018-06-11.

- SNH Loch Druidibeg Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 29 July 2007.

- "Loch Druidibeg handed over by Scottish Natural Heritage to community group". Press and Journal. 2018-05-19. Retrieved 2018-06-11.

- "South Uist Machair NSA 1:50,000 map" (PDF). Scottish Natural Heritage. 2010-12-20. Retrieved 2018-06-07.

- "National Scenic Areas". Scottish Natural Heritage. Retrieved 2018-06-07.

- "National Scenic Areas - Maps". SNH. 2010-12-20. Archived from the original on 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2018-06-05.

- Epping Forest Hedgehog Rescue Archived August 27, 2006, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- Ross, John (21 February 2007). "Hedgehogs saved from the syringe as controversial Uist cull called off". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Retrieved 2009-08-10.

- Paul Kelbie (2007-02-20). "Campaign wins reprieve for Uist hedgehogs". The Independent.

- http://www.hebrides-news.com/uist-climate-change-risk-4819.html

- http://dynamiccoast.com/files/reports/NCCA%20-%20Cells%208%20and%209%20-%20The%20Western%20Isles.pdf

- Census 2011 stats BBC News. Retrieved 20 April 20-14.

- "Alexander hears jobs and cuts fears". (27 Aug 2010) Aberdeen. Press and Journal.

Bibliography

- Ballin Smith, Beverley; Taylor, Simon; and Williams, Gareth (2007) West over Sea: Studies in Scandinavian Sea-Borne Expansion and Settlement Before 1300. Leiden. Brill. ISBN 97890-04-15893-1

- Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2003) Ainmean-àite/Placenames. (pdf) Pàrlamaid na h-Alba. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

External links

- The Island Where God Speaks Gaelic Raidió Teilifís Éireann documentary from 1971

- Archaeological Aerial Photographs

- 'South Uist a Hebridean First': Flag Institute press release 30 June 2017

- An Gàrradh Mòr, Historic walled garden at Cille Bhrìghde

- The world in a spin: representing the Neolithic landscapes of South Uist in Internet Archaeology

- Rocket launches at South Uist

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.