Olvir Rosta

Olvir Rosta (Old Norse: Ölvir Rósta, and Ölvir Þorljótsson), also known as Aulver Rosta, is a character within the mediaeval Orkneyinga saga, who is purported to have lived during the early 12th century. His Old Norse byname, rósta, means "brawl", "riot". His name, and byname, appear variously in English secondary sources.

Ölvir Rósta | |

|---|---|

| Known for | Appearing in the Orkneyinga saga |

| Parent(s) | Þorljót (father); Steinnvör 'the Stout' (mother) |

| Relatives | Ljótr 'Villain' (maternal grandfather); Frakökk (maternal grandmother); Moddan (father of Frakökk) |

| Notes | |

Relations and residences are all according to the Orkneyinga saga | |

Ölvir appears in the saga as the son of Þorljót, and Steinnvör 'the Stout'. The mother of Steinnvör is Frakökk, who has been described as one of the great villains of the entire saga. One of Frakökk's sisters, Helga, is the concubine of Earl Hákon Pálsson. Part of the saga relates of how the Earldom of Orkney is for a time jointly run by half-brothers—Haraldr Hákonsson and Páll Hákonsson, who are both sons of Earl Hákon. With the death of Earl Haraldr, son of Helga, Frakökk's family falls out of favour, and are forced to leave Orkney. In time, Frakökk conspire with the father of Earl Rögnvaldr, and agrees to a plan to take the Orkney by force and split it with Earl Rögnvaldr. She and Ölvir eventually make their way to the Suðreyjar, and may their return in a bid to win half of the earldom. However, their small fleet of ships are defeated in battle against Earl Páll. The saga also tells of how Ölvir kills an Orkney chieftain who fought against him during the sea-battle—by burning the man to death within his house. The chieftain's vengeful son later tracks down Ölvir and Frakökk, at their own home in Sutherland. After a short battle behind their homestead, Ölvir's men are routed and Frakökk is burned to death within her house; Ölvir flees from the scene, making for the Suðreyjar, and is not heard from again.

Ölvir has also been associated with several places in Sutherland, some of which may bear his name. It has been proposed that Ölvir Rosta may be an ancestor of either one of two Scottish clans from the Outer Hebridean Isle of Lewis. In 1962 a runestone was uncovered in the Inner Hebrides which bore the name Ölvir. It has been suggested that the men mentioned on this stone were family relations of Ölvir.

Background

Ölvir Rósta, is a character in the mediaeval Orkneyinga saga. His name in Old Norse is Ölvir rósta. The 17th-century Icelandic historian Þormóður Torfason, who wrote Latin histories which covered events the Northern Isles and north-east of Scotland, rendered Ölvir's name as Aulver Rosta.[1] Ölvir's byname, rósta, means "brawl", "riot".[2] Both his name and byname are represented various ways in English secondary sources.[note 1] The saga describes him as "the tallest of men, and strong in limb, exceedingly overbearing, and a great fighter".[13][14]

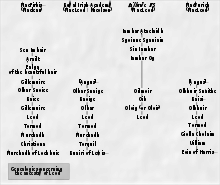

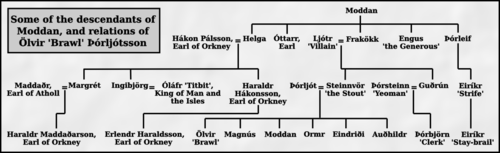

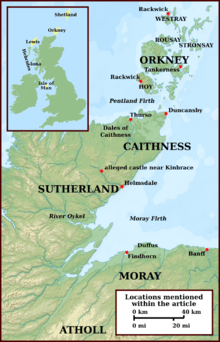

The Orkneyinga saga states that Ölvir was the son of Þorljót, from Rekavík. The 19th-century historian Joseph Anderson was of the opinion that Rekavík likely refers to Rackwick on the island of Hoy, Orkney; or possibly, but less likely, to Rackwick on the island of Westray, Orkney. The saga states that Ölvir's mother was Þorljót's wife, Steinnvör 'the Stout'.[11] Ölvir's parents had several other children in the saga: sons Magnús, Ormr, Moddan, Eindriði; and daughter Auðhildr.[8] Steinnvör's mother is given as Frakökk; her father was Frakökk's husband, Ljótr 'Villain', from Sutherland.[11] The saga states that Frakökk was a daughter of Moddan, a wealthy and noble farmer from i Dali, "Dale". According to 21st-century historian Gareth Williams, this probably refers to a dale within the "Dales of Caithness". The 21st-century historian Barbara Crawford stated that the Dales of Caithness refer to "that part of Caithness which includes the river valleys running down towards the Pentland Firth".[15] The saga records that another daughter of Moddan's was Helga, who was the concubine of the Orcadian earl, Hákon Pálsson, and the mother of the earl's son, Earl Haraldr Hákonsson.[11] According to the saga, Frakökk's brothers included: Engus 'the Generous'; and Earl Óttarr, from Thurso, who is described as "a man worthy of honour". The saga declares that the descendants of Moddan "were high-born and thought a lot of themselves",[8] and Williams suggested that they could be related to a powerful dynasty in the Irish Sea zone that included an Óttarr who seized control of the Kingdom of Dublin in 1142.[16] Williams noted that Frakökk appears as one of the great villains of the Orkneyinga saga. Williams noted that while some of Moddan's descendants had legitimate claims for the earldom, Frakökk did not—however, she made a claim on behalf of her descendants, specifically Ölvir.[8]

Williams was of the opinion that the power base of Moddan, and his son Earl Óttarr, was in Caithness and Sutherland, not in Orkney.[8] The saga states that Frakökk held lands, which according to Williams, were located near the modern town of Helmsdale, Sutherland. Williams noted that the saga specifically states that Frakökk's husband was from Sutherland. and in consequence, Williams considered that these lands probably passed to her through her marriage. The size of these lands is unknown. Crawford suggested that they covered most of Sutherland: that after the Frakökk's death, and the departure of Ölvir, the lands were inherited by her relative Eiríkr 'Stay-brail' (see illustrated family tree), and in turn by his son, before passing into the possession of the de Moravia family. In Williams' opinion, Crawford may have exaggerated the extent of these lands somewhat. Williams observed that another base of power for Frakökk and Ölvir may have been the Suðreyjar ("Southern Islands")—which can include both the Hebrides, and the Isle of Man. The saga states at one point, Frakökk and Ölvir travelled to the Suðreyjar to gather ships and men; later the Suðreyjar are the destination of Ölvir in his last appearance in the saga. Williams noted that the Suðreyjar appear many times in the sagas as a target for raids, and conquests, for Orcadian earls; as well as being the source for attacks on the earldom itself. Williams also noted that it is possible that saga's association of Frakökk and Ölvir with the Suðreyjar may be a red-herring. He stated that "if there was an Orcadian tradition of the Suðreyjar as a haunt of ne’er-do-wells, this would provide an alternative explanation for the references within Orkneyinga saga, including those to do with Moddan's family". Even so, Williams considered that the saga seems to imply that the family had dynastic connections with important individuals of the Suðreyjar, including 'Óláfr 'Titbit', King of Mann and the Isles.[15]

Orkneyinga saga

The main source for the life of Ölvir is the Orkneyinga saga, which was compiled sometime around 1200 by an unknown Icelander. The saga is thought to have been based upon poetry, oral tradition, and other written material. The original version ended with the death of Sveinn Ásleifarson (who is portrayed as an enemy of Ölvir and Frakökk). The saga is considered to become more accurate as events approach the writer's own time.[18] In the late 14th century, the saga was revised and edited and included in the Icelandic Flateyarbók. The saga can be summed up as an account of the lives of many of the earls of Orkney, from the 9th to 13th centuries. According to research fellow Ian Beuermann, the saga is useful not for the specific events it describes, but rather for the ability to learn of "the ideas shaping the texts during the periods of composition or revision". For example, it is possible that even one of the main characters of the saga, Sveinn Ásleifarson, never existed; or at least it is quite possible that the historical Sveinn was different from the saga's portrayal of him.[19] Another source which mentions Ölvir is Þormóður Torfason's 17th-century history of Orkney, which follows the Orkneyinga saga.

Frakökk, and Helga, forced out of Orkney by Earl Páll

The Orkneyinga saga relates how after the death of Earl Hákon Pálsson, his sons, Haraldr Hákonsson, and Páll Hákonsson, divided the earldom between themselves. However, the half-brothers soon began to disagree with one another, and their vassals divided into competing factions. The saga relates how one day Frakökk, and her sister Helga (mother of Earl Haraldr), were sewing a snow-white garment embroidered with gold. This garment was enchanted, and the two sisters had intended it for Earl Haraldr's half-brother, Earl Páll. Unfortunately for the sisters, Earl Haraldr noticed the beautiful garment and, despite their protestations, put the garment on and soon after died. The saga states that Earl Páll immediately took control of his deceased half-brother's possessions, and that he was highly suspicious of the two sisters. In consequence, Frakökk and Helga were no longer welcome in the earldom, and they left for Caithness, and from there move to Sutherland where Frakökk had an estate. In time, several of Frakökk's descendants were brought up in Sutherland—including her daughter, Steinnvör 'the Stout', and grandson, Ölvir.[11]

Alliance with Earl Rögnvaldr against Earl Páll

The saga relates of how, during an earlier time, Kali Kolsson assisted Haraldr Gille in being recognised as an illegitimate son of the deceased Norwegian king, Magnús 'Barefoot'.[20] In consequence, the reigning king, Sigurðr Magnússon, was Haraldr Gille's half-brother. The Norwegian king, appointed Kali as an earl of one half of Orkney, and also had Kali's name changed to Rögnvaldr (after a prominent earl from the past).[21] On the death of Sigurðr, his son, Magnús Sigurðarson, succeeded to the kingdom. When Haraldr Gille learned of Sigurðr's death he gathered his supporters and successfully underwent an ordeal to prove his paternity, and was accepted as king of one half of the kingdom. For three years the joint-kings maintained an uneasy peace with one another, but on the fourth year hostilities finally broke out. A battle was fought where the vastly outnumbered Haraldr Gille was defeated; in consequence he fled to the protection of the King of Denmark. The following Yule-tide, Haraldr Gille returned to Norway, captured Magnús and maimed him. Haraldr Gille then became king of the entire kingdom. That spring, in recognition for Rögnvaldr's assistance, the king renewed the grant of islands and the title of earl to Rögnvaldr.[22] James Gray, who summarised the events depicted within the saga, dated the death of Sigurðr Magnússon to the year 1126; he dated the capture and mutilation of Magnús Sigurðarson to 1135.[23]

According to the saga, sometime after Haraldr Gille's victory over Magnús Sigurðarson, Earl Rögnvaldr's father, Kolr, sent messengers to Earl Páll, demanding that Earl Páll hand over the lands which the Norwegian king had granted to Earl Rögnvaldr. When Earl Páll refused this, Kolr's messengers proceeded to Caithness, where Frakökk lived. The messengers related to Frakökk of Kolr's proposal—that if she and Ölvir were to defeat Earl Páll, half of the earldom would be theirs. Frakökk agreed to the plan, saying that she would attack in mid-summer; she promised that during upcoming winter she would gather forces from her kinsmen, friends, and connections in Scotland and the Suðreyjar for the task. The next winter Earl Rögnvaldr and two of his chiefs, Sölmundr and Jón, gathered a force of men and about five or six ships for their expedition. The following summer their forces sailed from Norway to Shetland, where they were well received by the local bondsmen. Meanwhile, Frakökk and Ölvir assembled a small fleet of twelve ships in the Suðreyjar—although the saga describes the ships as small and poorly manned. At the middle of summer, Frakökk and Ölvir sailed for Orkney to fulfil their pledge of wresting the earldom from Earl Páll.[24]

Sea-battle against Earl Páll

According to the Orkneyinga saga, when Earl Páll herd of Earl Rögnvaldr's arrival in Shetland, he held council and decided to immediately gather forces and attack Earl Rögnvaldr before he could be reinforced by the incoming men he knew were coming from the Suðreyjar. That night Earl Páll was joined by five chieftains, with four ships—this brings his total forces to five ships. The fleet sailed to Rousay, where they arrive at sunset. During the night the force is further strengthened by arriving men. In the morning, as the fleet is about to set out for Shetland to meet Earl Rögnvaldr, about ten or twelve ships were spotted coming from the Pentland Firth. Earl Páll and his men were certain these ships were those of Frakökk and Ölvir; in consequence, the earl ordered the fleet to intercept. The saga states that when Ölvir's ships were east of Tankerness, they then sailed west from Mulls Head, Deerness. By this time, Earl Páll was further strengthened by a chieftain from Tankerness. The earl then ordered his ships to be bound together, and for a bondi to gather stones for the upcoming battle. When the earl and his troops have fully prepared themselves, the saga states that Ölvir's forces made their attack.[25]

Although the saga states that the forces of Ölvir were superior in numbers to those of Earl Páll, it also notes that Ölvir's ships were smaller. Ölvir brought his own ship up next to the earl's, where the fighting was the fiercest. One of the earl's chieftains, Ólafr Hrólfsson, attacked Ölvir's smallest ships, and cleared three of them in a short time. Ölvir urged his men forward and was the first to board Earl Páll's own ship. When he spotted Earl Páll, Ölvir threw a spear at him, and although it was blocked by a shield, the force of the blow knocked the earl onto the deck. With the fall of Earl Páll, a great shout goes up; but just at that moment, one of the earl's best men, Sveinn 'Breastrope', hurled a large stone at Ölvir, hitting him square in the chest and knocked him overboard. Although Ölvir's men dragged him from the water, it was unclear to the battlers whether he lived or not. Ölvir's disheartened men were driven off the earl's ship, and began to withdraw. Ölvir eventually recovered his wits, but was unable to rally his troops—the battle was lost. Earl Páll pursued Ölvir's fleeing fleet into the Pentland Firth, before giving up the chase. Five of Ölvir's ships were left behind, and were captured and manned by the forces loyal to Earl Páll. The earl is later further strengthened by two longships, and his forces swells to twelve ships. The next day, Earl Páll sailed to Shetland, where he destroyed Earl Rögnvaldr's fleet. Although, Earl Rögnvaldr's forces remained in Shetland itself, Earl Páll successfully held onto the earldom.[25] Gray stated that these battles were fought in the year 1136.[26]

Burning of Óláfr Hrólfsson

The Orkneyinga saga states that three days before Yule, Ölvir, and his band of men, arrived in Duncansby.[27] Williams stated that the farm of Duncansby, located near the Dales of Caithness, was then in hands of an Orkney chieftain, Óláfr Hrólfsson.[8] Joshua Prescott stated that Óláfr appears to have been Earl Páll's main supporter in Caithness;[28] according to Williams, Óláfr appears to have held these lands directly from the Earls of Orkney, rather than as a family possession.[8] The saga relates of how at Duncansby, Ölvir and his party surprised Óláfr within his own house. They then set fire to the house, and burn Óláfr to death within. Ölvir and his men took all the movable property they could get their hands on, before leaving the scene. When Earl Páll heard of what has happened, he takes-in the slain chieftain's son, Sveinn Óláfsson. With the death of his father, Sveinn Óláfsson becomes known as Sveinn Ásleifarson—after his mother.[27] Such house-burnings—in which individuals are burnt to death, or slain as they flee the fire—are found throughout the sagas as a part of blood feuds.[7] The saga states that some time later, Sveinn, who has spent time in the Suðreyjar and Atholl, returned to Orkney. On his way, Sveinn he stopped at Thurso, where his accomplice, Ljótólfr, negotiated a truce between Sveinn and Frakökk's brother, Earl Óttarr. The earl paid Sveinn compensation for the death of Óláfr, and promised his friendship. In return, Sveinn promised to aid Earl Óttarr's relative, Erlendr Haraldsson, in a possible bid for the earldom of Orkney.[29]

Defeat of Ölvir, and the burning of Frakökk

The saga states that some time later, Sveinn approached Earl Rögnvaldr, and asked the earl for men and ships to take vengeance upon Ölvir and Frakökk who were involved in the burning of his father. The earl consented to this request, and gave Sveinn two ships. Sveinn travelled south to Borgarfiörd, and then west to the trading place of Dúfeyrar. According to Anderson, Borgarfiörd may refer to the Moray Firth; and Dúfeyrar likely refers to the shore in the parish of Duffus, on the coast of Moray. The saga states that from Dúfeyrar, Sveinn travelled to Ekkialsbakki, and from there went to Atholl, where he met Earl Maddaðr.[30] Anderson stated that Ekkialsbakki, in this case, likely refers to the coast on the Moray Firth, next to Atholl;[31] The 19th-century historian William Forbes Skene agreed with this, specifically locating it to Findhorn, where ships could enter an estuary and follow a route into Atholl.[32] However, Hermann Pálsson and Paul Geoffrey Edwards, in their 1981 translation of the saga, identified the town of Banff with Dúfeyrar, and the River Oykel with Ekkialsbakki.[33]

The saga then relates how the Earl Maddaðr gave Sveinn guides, and how Sveinn travelled through the interior of the country—over mountains, and through woods, away from inhabited areas—until he came upon Strath Helmsdale, near where Ölvir and Frakökk lived.[30] Williams stated that since the saga records that Sveinn approached the area by land, the site of Ölvir and Frakökk's estate was probably located somewhere in the dale of Helmsdale—not where the modern village is situated on the coast. Williams also noted that this area was quite remote from Orkney, and that it may have been outside of the control of the earldom.[8] The saga states that Ölvir and Frakökk had spies on the lookout; however, because of the route taken by Sveinn, they were unaware of his presence until Svienn occupied a certain slope behind their homestead. The saga states that Ölvir and sixty of his men confronted Sveinn,[30] although Þormóður Torfason's account of the incident gives forty.[1] After a short clash, the saga states that, Ölvir's men soon gave way, and many were killed in the ensuing rout. Ölvir survived the clash, and fled up Helmsdale river. Meanwhile, Sveinn and his men continued on towards the houses. The area was plundered, and the houses were burnt to the ground with their inmates still inside—and in this way Frakökk perished. The saga states that Sveinn and his men committed many ravages in Sutherland before returning home. Upon reaching the river, Ölvir fled through the mountains, and is last heard making for the Suðreyjar; he is not mentioned again within the Orkneyinga saga.[30][note 2] Later on within the saga, another of Frakökk's grandsons, Þórbjörn 'Clerk', who is a brother-in-law and close friend of Sveinn, has two of Sveinn's men killed for their part in the burning.[37]

While the saga records that Frakökk was killed to avenge the burning of Óláfr, recently scholars Angelo Forte, Richard Oram, and Frederick Pedersen, stated that her fate was actually sealed by her support of Erlendr Haraldsson's bid for the earldom, over the claim of Haraldr Maddaðarson. Haraldr was the son of Earl Maddaðr, and Margrét Hákonardóttir (married in about 1134). Margrét was a niece of Frakökk, and Earl Maddaðr was possibly a cousin of the David I. The union between Earl Maddaðr and Margrét benefited the Scottish Crown by increasing Scottish influence in the north at the expense of Norwegian influence. Also, in the 1120s and 1130s, David I had faced challenges to his authority. A large part of the support for these challengers came from Moray and Ross—these lands were directly between the northern lands of Caithness and Orkney, and David's strength to the south. According to the Forte, Oram, and Pedersen, the prospect of having the son of one of his northern supporters as the earl of Caithness was too good for the king to pass up—especially since Haraldr was still a minor, and would thus be under the direction of an appointed tutor. As it turned out, the installation of Haraldr as an earl of Orkney and Caithness was a triumph for the Scottish Crown: in the 1140s, Sutherland and Caithness were further integrated into the kingdom, and the Norwegian influence in Orkney was neutralised.[38][note 3]

Locations associated with Ölvir, Frakökk, and Sveinn

Several writers have noted a place which is said to be the location of the burning. The CANMORE website states that a supposed castle in which Frakökk was burned may be located at grid reference NC8728, near Kinbrace, within the parish of Kildonan.[39] In 1769, Thomas Pennant noted the episode of the burning, and stated that certain ruins at Kinbrace were called "Cairn Shuin"; and that these were the remnants of the homestead that Sveinn burnt.[40] Rev. Sage, in his account of the parish in the (Old) Statistical Account of Scotland, noted the ruins mentioned by Pennant; he called them "Cairn-Suin", and translated this to "Old Cairns". Sage, however noted Þormóður Torfason's account of the burning, and suggested that a possibly more accuarate etymology is "Suenes Field".[41] Pennant stated that "though the ruins are great, yet no man can tell of what kind they were; that is, whether round like Pictish houses, or not". According to the CANMORE website, Pennant may have been referring to any of the chambered cairns in the area.[39] The site of the supposed castle was visited by the Ordnance Survey in 1961, but no evidence of it was found.[39] In the mid-19th century, Alexander Pope noted "Carn Suin", and stated that nearby there were certain ruins called "Shu Carn Aulver". Pope also stated that to the south-west of this location there was a part of Helmsdale river called "Avin Aulver". Another location he connected with Ölvir was a hill, in the forest of "Sletie", called "Craggan Aulver".[35]

Speculation of Scottish descendants

According to Williams, it is possible that after Sveinn defeated Ölvir and Frakökk, Ölvir may have fled to kinsmen of his in the Suðreyjar. Williams suggested that the blood feud between the families may be a reason for Sveinn's military activities in the Hebrides and the Isle of Mann, afterwards; although Sveinn had other interests in the area, since he is stated to have married the window of a Manx king.[42] In the late 19th century, antiquary F.W.L. Thomas speculated that the memory of Ölvir may have been preserved in the Hebrides. Thomas stated that within the mythological history of the Outer Hebridean Isle of Lewis, the island clan of Macaulays were said to be the descendants of a man named Amhlaebh, who was one of the twelve sons, or near relations, of a man named Oliver, among whom Lewis was divided. This Oliver was said to have been the eldest son of the Norse king who was given the Isles and Highlands by a son of Kenneth MacAlpin, for his assistance in driving his own brother from Scotland.[9] Thomas speculated that Oliver could represent Ölvir Rósta; meaning that he was the progenitor of the Macaulays.[9][43][44]

It has also been suggested that Ölvir may be an ancestor of the MacLeods. Until quite recently, it was commonly believed by historians that the eponymous ancestor of the MacLeods, Leod, was the son of Olaf the Black, King of Mann and the Isles. In the late 20th century, William Matheson proposed that the MacLeods descended in the male line from Ölvir Rósta, rather than Olaf the Black. Matheson proposed that, within several Gaelic pedigrees which record ancestors of Leod, the great-grandfather of Leod has Gaelic names which very likely represent the Old Norse name Ölvir.[14] These Gaelic names are considered to equate to other Gaelic names found within the early bardic poetry of the MacLeods.[12] About a century before, Thomas had noted the similarity in these names, when discussing Ölvir, but he did not pursue a specific link between Ölvir and the MacLeods.[45] Matheson speculated that Leod's great-grandfather would have flourished at roughly the same time as when Ölvir is said to have fled to the Suðreyjar. Matheson noted that Leod's name is derived from the Old Norse name Ljótr: a name which Matheson considered to be rare in Scandinavia and Iceland, and even more so in Scotland. In consequence, he considered it significant that Ölvir's maternal grandfather (Ljótr 'Villain') also had this name. When comparing the relevant Gaelic pedigrees, Matheson noted that they were inconsistent in the generations preceding Leod's great-grandfather. In lieu of this, Matheson proposed that these inconsistencies may show that the Leod's great-grandfather was a newcomer to the Hebrides, like Ölvir.[14]

Later, historian W.D.H. Sellar noted Matheson's proposed link between the MacLeods and Ölvir, but commented that the evidence Matheson used was entirely circumstantial. Sellar was of the opinion that Ölvir was not such a rare name as Matheson had previously thought. Sellar also noted that the genealogy and family of Ölvir, recorded in the Orkneyinga saga, has no similarity with the line recorded in the Gaelic genealogies concerning the ancestry of Leod.[45] Matheson's association of Ölvir to the Macleods was also attacked by clan historian Alick Morrison. Morrison commented that the name Ljotr was also not as rare as Matheson had proposed. Morrison noted that, in the previous century, Thomas had considered another saga character to be an eponymous ancestor of the MacLeods—this character was Ljótólfr (mentioned earlier in the article), who would have lived on Lewis about a century before Leod's time.[46][47] In fact, Morrison did not consider Ölvir's name—and the singled-out Gaelic names—to be anything but other forms of Óláfr.[46][note 4] However, Óláfr and Ölvir are considered by others to be quite different names, with separate origins.[12] Morrison, and Sellar, also noted that the bynames of Ölvir, and Leod's great-grandfather, do not appear to match up[45][46]—in three of the relevant Gaelic pedigrees, the byname of Leod's great-grandfather appears as snoice, snaige, and snáithe.[45] Thomas considered these bynames to mean "hewer";[9] although, both Matheson and Sellar disagreed with this translation.[14][45] Morrison considered these to equate to snaith, "white";'[46] however, Sellar noted that Morrison gave no further explanation for this assertion. Sellar, himself, proposed that the byname may be not be Gaelic, but Norse in origin. He suggested that it may refer to some sort of deformity to the man's nose; another suggestion forwarded to him was that it may refer to a cleft palate.[45] Later, A.P. MacLeod noted that the Gaelic snatha—which has a secondary meaning of "grief", and "trouble"[48]—may be a nominative form of the genitive snaithe, and thus may equate to Ölvir's byname.[12]

Hebridean runes: possible family connections

In 1962, on the Inner Hebridean island of Iona, close to Reilig Odhrain grid reference NM286245, a fragment of a carved stone bearing the runic inscription of a man named Ölvir was found.[49] It is one of only three examples of rune-stones found in the west of Scotland.[50] The fragment is about half the size of the original stone,[51] which would have measured 1.11 by 0.77 metres (3.6 by 2.5 ft). The stone is decorated with a crude knotted cross;[52] the runes are located on the side, along the border. At the end of the inscription there are a few runes missing, due to the corner having been broken off.[51] The full inscription translates into English: "Kali, son of Ölvir, laid this stone over Fugl his brother". These three men do not appear in any other sources, and it is unknown who they were. In the 1980s, Norwegian runologist Aslak Liestøl proposed that the stone is evidence that the two brothers were Scandinavian speakers, who were members of a leading family in the district, who had the social status to be buried near Reilig Odhrain.[51] The runic inscriptions, and artwork, suggests that the stone dates to the late 10th century, or 11th century.[49]

Liestøl suggested that the three men were somehow related to Ölvir. Liestøl noted that three names were those of characters in the Orkneyinga saga, which all had connections with the Hebrides. Kali was the original name of Earl Rögnvaldr, whom Ölvir fought for. The earl was named after his grandfather, Kali Sæbjörnarson, who according to the saga, accompanied Magnús 'Barefoot' to the Hebrides, and died there of wounds he received on Anglesey.[51] According to Liestøl, the name Fugl, in a West Norse context, is only found on this inscription and of a minor character in the saga.[51] This character was the son of Ljótólfr, from Lewis, who negotiated a truce between Sveinn Ásleifarson and Earl Óttarr. In 1922, historian Alan Orr Anderson noted that the mediaeval Chronicle of Man records that Fogolt, sheriff of Man, died in 1183, and Anderson stated that it is possible that Ljótólfr's son was the mentioned sheriff.[53] Concerning the name Ljótólfr, Liestøl also noted that the saga names Ölvir's father Þorljót, and his maternal-grandfather Ljótr. He concluded that the men mentioned on the stone likely lived around the year 1000, about four to six generations before their namesakes in the saga. In consequence, Liestøl suggested that Kali Sæbjörnarson would have been a contemporary of the children of the rune-stone's Kali Ölvisson.[51] The stone, among many others, is housed in the museum at Iona Abbey.[49]

| Script, and languages | Inscription, transliteration, and translations |

|---|---|

| Runic inscription[54][note 5] | ᚴᛆᛚᛁ᛫ᚮᚢᛚᚢᛁᛌ᛫ᛌᚢᚿᚱ᛫ᛚᛅᚦᛁ᛫ᛌᛐᛅᚿ᛫ᚦᛁᚿᛌᛁ᛫ᚢᚭᛁᚱ᛫ᚠᚢᚴᛚ᛫ᚭᚱᚢᚦᚢᚱ |

| Latin script transliteration[55] | kali᛫auluis᛫sunr᛫laþi᛫stan᛫þinsi᛫ubir᛫fukl᛫bruþur [᛫sin][note 6] |

| Old Norse translation[54] | Kali Ölvissonr lagþi stein þenna yfir Fugl broður [sinn] |

| English translation[49] | Kali, son of Ölvir, laid this stone over Fugl his brother |

Notes

- Over the years, Ölvir Rósta has been referred to within English secondary sources with various names: Aulver Rosti,[3] Aulver the Brawler,[4] Oliver rosti,[5] Olvi Riot,[6] Ölvi the Unruly,[7] Olvir Brawl,[8] Olvir Rosta,[9] Olvir the Riotous,[10] and Olvir the Turbulent;[9] his byname has also been rendered into English as "strife".[11][12]

- Pennant, within his late 18th-century description of the parish of Creich, in Sutherland, stated that the following: "In the 11th or 12th century lived a great man in this parish, called Paul Meutier. This warrior routed an army of Danes near Creich. Tradition says that he gave his daughter in marriage to one Hulver, or Leander, a Dane; and with her, the lands of Strahohee; and that from that marriage are descended the Clan Landris, a brave people, in Rosssshire [sic]".[34] In the mid-19th century, Pope translated Þormóður Torfason's history of Orkney and stated the following in a footnote: "As for Aulver Rosta, the author [Þormóður Torfason] gives no further account of him, but it is probable he was the same person that married Paul Mactier's daughter, and got with her the lands of Strath Okel; for he is called a Dane or Norweigian [sic], and Aulver is the same name with Leander. The Paul was a powerful man that lived in Sutherland. It is a common tradition, that Paul Mactier gave the lands of Strath Okel as a patrimony to his daughter, who was married to a nobelman [sic] of Norway, called Leander. His posterity are called Clan Landus".[35] The historical Paul Mactire lived in the 14th century, and, according to tradition, was a member of Clann Ghille Ainnriais, a family which descended from a man named Gille Aindrais. A 17th-century tradition stated that the daughter of this Paul married a Ross of Balnagown, and from then on the Rosses were known in Gaelic as "Clan Leamdreis" (Clann Gille Ainnrais).[36]

- Forte, Oram, and Pedersen, noted that the saga also depicts Sveinn Ásleifarson as Earl Maddaðr and Margrét's instrument of removal of Earl Páll (who was also Margrét's own half-brother).[38] Also note that Erlendr Haraldsson, and Haraldr Maddaðarson were cousins—both were grandsons of Frakökk's sister Helga, and Earl Hákon Pálsson (see illustrated family tree).

- Morrison was convinced that Leod was the son of Olaf the Black, and thus not a male-line descendant of Ölvir Rósta. Historically, the grandfather of Olaf the Black was Óláfr 'Titbit' (mentioned earlier in the article). To help bolster his argument that Ölvir's name—and the Gaelic names—equate to Óláfr, Morrison quoted an 18th-century traditional account of Leod's father, which claimed the names were one and the same: that "the father of Leod, the eponymous of the Clan MacLeod, was Olave, or Olgair, Olaus or Auleus, King of Man and the Isles".[46]

- Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of runes.

- The border of the fragment is broken, however, the missing space after bruþur is thought to have been inscribed with the runic equivalent of sin, meaning "his" (as in "Fugl his brother").[49]

References

- Pope 1866: pp. 94–130.

- Vigfusson 1874: pp. 501, 503.

- Sutherland 1881: p. 59.

- Carr 1864–66: p. 78.

- Thomson 2008: p. 112.

- Anderson, AO; Anderson, MO 1990: pp. 191–192.

- Johnson 1912: pp. 157–165.

- Williams 2007: pp. 129–133.

- Thomas 1879–80: p. 364.

- Moncreiffe of that Ilk 1967: p. 160.

- Anderson, J 1873: pp. 69–73.

- "The Ancestry of Leod". www.macleodgenealogy.org. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2009. This webpage cited: MacLeod, Andrew P. (2000). "The Ancestry of Leod". Clan MacLeod Magazine. No. 91.

- Roberts 1999: p. 129.

- "The Ancestry of the MacLeods". www.macleodgenealogy.org. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2010. This webpage cited: Matheson, William (1978–80). "The MacLeods of Lewis". Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness. Inverness. 51: 68–80.

- Williams 2007: pp. 133–137.

- Williams 2007: pp. 142, 149–150.

- Vigfusson 1887: pp. xxxvi–xxxvii.

- Pálsson; Edwards 1981: pp. 9–12.

- Beuermann, Ian. "A Chieftain in an Old Norse Text: Sveinn Ásleifarson and the Message behind Orkneyinga Saga" (PDF). www.cas.uio.no. Archived from the original (pdf) on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 21 March 2010.

- Anderson, J 1873: pp. 75–76.

- Anderson, J 1873: pp. 82–83.

- Anderson, J 1873: pp. 83–85.

- Gray 1922: p. 61.

- Anderson, J 1873: pp. 85–87.

- Anderson, J 1873: pp. 87–90.

- Gray 1922: p. 62.

- Anderson, J 1873: pp. 91–92.

- "University of St Andrews Digital Research Repository: Earl Rognvaldr Kali: crisis and development in twelfth-century Orkney". University of St Andrews. Retrieved 5 March 2010. The specific link to the cited thesis is: Prescott, Joshua (June 2009). "Earl Rognvaldr Kali: crisis and development in twelfth-century Orkney" (pdf). University of St Andrews. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- Anderson, J 1873: pp. 105–106.

- Anderson, J 1873: pp. 114–116.

- Anderson, J 1873: p. 107.

- Skene, 1886: p. 337.

- Pálsson; Edwards 1981: p. 144.

- Pennant 1769: pp. 360–361.

- Pope 1866: pp. 131–132.

- Grant 2000: pp. 113–115.

- Anderson, J 1873: pp. 118–119.

- Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005: pp. 283–287.

- "Kinbrace". CANMORE. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- Pennant 1769: pp. 361–363.

- The (Old) Statistical Account of Scotland. "Account of 1791–99 vol.3 p.410 : Kildonan, County of Sutherland". EDINA. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- Williams 2007: pp. 137–149.

- Mackenzie 1903: p. 64.

- Gray 1922: pp. 59, 61–62, 64, 72, 76, 148n20.

- "The Ancestry of the MacLeods Reconsidered". www.macleodgenealogy.org. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 8 December 2009. This webpage cited: Sellar, William David Hamilton (1997–1998). "The Ancestry of the MacLeods Reconsidered". Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness. 60: 233–258.

- "The Origin of Leod". www.macleodgenealogy.org. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2010. This webpage cited: Morrison, Alick (1986). The Chiefs of Clan MacLeod. Edinburgh: Associated Clan MacLeod Societies. pp. 1–20.

- Vigfusson 1887: pp. xxxvii–xxxviii.

- Dwelly 1902: p. 864.

- "Iona, Iona Abbey Museum". CANMORE. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- Graham-Campbell 1998: p. 43.

- Liestøl 1983: pp. 85–94.

- Crawford 1987: pp. 178–179.

- Anderson 1922: p. 259.

- Graham-Campbell 1998: p. 252 figure 13.3.

- Page 1987: p. 59.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Joseph, ed. (1873), The Orkneyinga saga, Translated by Jón Andrésson Hjaltalín, and Gilbert Goudie, Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas

- Anderson, Alan Orr (1922), Early Sources of Scottish History: A.D. 500 to 1286, 2, Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd

- Anderson, Alan Orr; Anderson, Marjorie Ogilvie (1990), Early sources of Scottish history, A.D. 500 to 1286, 2, Paul Watkins, ISBN 978-1-871615-05-0

- Carr, Ralph (1864–66), "Observations on some of the Runic Inscriptions at Maeshowe, Orkney" (pdf), Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 6

- Crawford, Barbara E. (1987), Scandinavian Scotland, Scotland in the Early Middle Ages, Leicester University Press, ISBN 0-7185-1197-2

- Dwelly, Edward (1902), Faclair Gaidhlig [A Celtic Dictionary: specially designed for beginners and for use in schools], 3, Herne Bay, Kent: E. Macdonald & Co., at the Gaelic Press

- Forte, Angelo; Oram, Richard; Pedersen, Frederik (2005), Viking Empires, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-82992-2

- Graham-Campbell, James; Batey, Colleen E. (1998), Vikings in Scotland: An Archaeological Survey, Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 978-0-585-12257-1

- Grant, Alexander (2000), "The Province of Ross and the Kingdom of Alba", in Cowan, Edward J.; McDonald, R. Andrew (eds.), Alba: Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages, East Linton: Tuckwell Press, ISBN 1-86232-151-5

- Gray, James (1922), Sutherland and Caithness in saga-time; or, The jarls and the Freskyns, Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd

- Johnson, Alfred W. (1912), "Some Medieval House-Burnings by the Vikings of Orkney", The Scottish Historical Review, Glasgow: James Maclehose and Sons, 12

- Liestøl, Aslak (1983), "An Iona rune stone and the world of Man and the Isles", in Fell, Christine; Foote, Peter; Graham-Campbell, James; et al. (eds.), The Viking Age In The Isle of Man: Select papers from The Ninth Viking Congress, Isle of Man, 4–14 July 1981, Viking Society for Northern Research University College London, ISBN 0-903521-16-4

- Mackenzie, William Cook (1903), History of the Outer Hebrides, Paisley: Alexander Gardner

- Moncreiffe of that Ilk, Iain (1967), The Highland Clans, London: Barrie & Rockliff

- Page, Raymond Ian (1987), Runes, Reading the Past, 4 (4th, illustrated ed.), University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-06114-9

- Pálsson, Hermann; Edwards, Paul Geoffrey, eds. (1981), Orkneyinga saga: the history of the Earls of Orkney (Reprint ed.), Edinburgh: Penguin Classics, ISBN 978-0-14-044383-7

- Pennant, Thomas (1769), A Tour in Scotland: MDCCLXIX (4th ed.), London: Printed for Benjamin White

- Torfæus, Thormodus (1866), Pope, Alexander (ed.), Ancient History of Orkney, Caithness, & the North, Wick: Peter Reid

- Roberts, John Leonard (1999), Feuds, Forays and Rebellions: History of the Highland Clans 1475–1625 (Illustrated ed.), Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 978-0-7486-6244-9

- Skene, William Forbes (1886). Celtic Scotland: A History of Ancient Alban. 1 (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: David Douglas.

- Sutherland, George Miller (1881), "Notes on Caithness History: The Keiths and Gunns", in Mackenzie, Alexander (ed.), The Celtic Magazine: A Monthly Periodical devoted to the Literature, History, Antiquities, Folk Lore, Traditions, and the Social and Material Interests of the Celt at Home and Abroad, 6, Inverness: A. & W. Mackenzie

- Thomas, F.W.L. (1879–80), "Traditions of the Macaulays of Lewis" (pdf), Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 14

- Thomson, William P.L. (2008), The New History of Orkney, Edinburgh: Birlinn, ISBN 978-1-84158-696-0

- Vigfusson, Gudbrand, ed. (1887), Icelandic sagas and other historical documents relating to the settlements and descents of the Northmen on the British isles, 1, London: Printed for Her Majesty's Stationery Office, by Eyre and Spottiswoode

- Vigfusson, Gudbrand (1874), An Icelandic-English Dictionary, based on the ms. collections of the late Richard Cleasby, Introduction by George Webbe Dasent, Oxford: Clarendon Press

- Williams, Gareth (2007), "'These people were high-born and thought a lot of themselves': A family of Moddan of Dale", in Smith, Beverley Ballin; Taylor, Simon; Williams, Gareth (eds.), West Over the Sea: Studies in Scandinavian Sea-Borne Expansion and Settlement Before 1300, The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400-1700 AD. Peoples, Economies and Cultures, 31, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-15893-1, ISSN 1569-1462