Cotter family

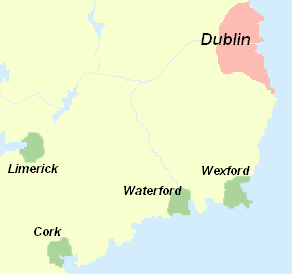

The Norse-Gaelic Cotter family (Irish Mac Coitir or Mac Oitir) of Ireland, was associated with County Cork and ancient Cork city. The family was also associated with the Isle of Man and the Hebrides.

| Cotter | |

|---|---|

| Current region | Throughout Ireland and the Irish diaspora, still numerous in County Cork. |

| Earlier spellings | Mac Cotter, Mac Coitir, Mac Oitir. |

| Etymology | Son of Óttar. |

| Place of origin | Cork city Ireland, of Norse-Gael ancestry. |

| Connected families | The Cottier family of the Isle of Man are reputed to be distantly connected. The Coppinger and Skiddy families of Cork are also claimed to have Norse-Gael origins. |

| Distinctions | Baronets of Rockforest. |

| Traditions | Claim descent from Óttar of Dublin a 12th century Norse-Gael king. |

| Estate(s) | Coppingerstown Castle, Inismore, Anngrove (historical). |

Evidence suggests an ultimately Norwegian origin of the name.

Norse origins

The Cotters are noted as one of the very few Irish families of verifiable Norse descent to survive the Norman invasion of Ireland,[1] although it is currently unknown if this is genetically paternal or only maternal. This question mattered considerably less to the Norse of the period than to the Gaelic Irish, whose entire rigid class structure was and remains based on agnatic descent.

A family manuscript of later date claims the Cotters are descendants of Óttar of Dublin (Son of Mac Ottir), who was King of Dublin from 1142 to 1148, through his son Thorfin and grandson Therulfe. This is not impossible, nor even improbable, but currently remains unverified, the greater part of the history of the Norse in Ireland, and especially those in Munster, being lost. The Gaelic Mac Coitir was originally Mac Oitir, literally meaning "Son of Óttar", but by common Irish and Scots usage implying a 'descendant of Óttar'.[2]

Ottar dynasty

Óttar of Dublin belonged to what has been referred to as the Ottar dynasty, a family of powerful jarls and sometimes kings of the Irish Sea region and surrounding waters, characterised by the repeated use of the personal name Óttar.

There is a record of a possible member of the dynasty, one Óttar Svarti ("Ottar the Black" - in Irish it would have been rendered 'Oitir Dubh'), an Icelander (connections between Iceland and the Norse settlements in Scotland and Ireland were relatively close), addressing Cnut, King of England and Denmark, in a praise-poem: "Let us greet the king of the Danes, the Irish, the English and the Islanders; his praise travels through all the lands under heaven." The connection between Norse aristocrats and poetic abilities is well attested.[3]

Ottir Iarla

The only Óttar associated with Munster in the Irish sources is one Jarl Ottar or Ottir Iarla also known in Irish as Ottir Dub (Óttar the Black), who makes appearances in the famous Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib. In that he is associated with the Viking settlement of Cork.[4] It states that after the combined forces of him and Ragnall ua Ímair raided a number of places in Munster, they then split into three parties, one of which settled in Cork. From other accounts it would appear this Ottir had a significant career in Scotland and England as well.[5] He is also later reported in the Cogad to have conquered and received tribute from the whole of eastern Munster from his seat at Waterford.[6] Ottir appears to have joined Ragnall in battle, or possibly led an expedition of his own, against Constantine II of Scotland in or around the year 918, and perished then,[7] for which see his article.

Lacking sources, it cannot be demonstrated that the Cotters of Cork or Mac Ottir of Dublin descend from this Jarl Ottar, but he did live in the right period for his name to be adopted as a surname. For example, the famous O'Neill dynasty take their name from his contemporary Niall Glúndub, who also died in battle.

Ottir Dub

In 1014 a Norse-Gael leader called Ottir Dub (Óttar the Black), a possible descendant of Ottir Iarla, is recorded as fighting on the side of Sigtrygg Silkbeard the King of Dublin against Brian Boru, High King of Ireland, at the Battle of Clontarf. In the battle Ottir led a sub-division of the Norsemen of Dublin, who were under the overall command of Dubgall son of Amlaíb. The Annals of Ulster state: "...of the Foreigners there fell Dubgall son of Amlaíb, Sigurðr son of Hloðver jarl of the Orkneys, and Gilla Ciaráin son of Glún Iairn heir-designate of the Foreigners, and Ottir Dub and Suartgair and Donnchad ua Eruilb and Griséne and Luimne and Amlaíb son of Lagmann and Broðar who killed Brian, commander of the fleet of the Lochlannaig, and 6000 who were killed and drowned."[8] In Cogadh Gaedhil re Gallaibh Ottir Dub is referred to as one of the four king's deputies (also translated as "petty kings") and admirals of the Vikings; as "king's deputies" they are likely to have been deputies to King Sigtrygg of Dublin.

Jarl Óttar of Man (Otter Fitz Therulfe)

The chronology and nature of Jarl Óttar's rule in the Isle of Man is unclear, though his death in battle on the island in 1098 is consistently referred to. One version states that in 1095 King Magnus Barefoot of Norway took control of the Isle of Man with a fleet of 160 ships. He placed a Hebridean or Norwegian jarl named Óttar as his vassal ruler over the island. Óttar is said to have alienated the inhabitants of the southern part of the island, who rebelled under a chieftain named MacManus or Macmaras.[9] According to the Chronicle of Man, however: "In 1098 there was a battle between the Manxmen at Santwat, and those of the North obtained the victory. In this contest were slain the Earl Other, and Macmaras, leaders of the respective parties." The chronicle then states that the after effects of this Manx civil war was the reason that Magnus Barefoot was able to take the island with ease later the same year. Magnus is said to have visited the site of the recent battle where unburied remains were still evident.[10] If the latter version is accurate then Óttar would appear to have been a sovereign prince within the island before the arrival of Magnus Barefoot, rather than a royal vassal. All versions agree that in 1098 a battle was fought between the forces of Óttar, with many men from the north of the island adhering to his cause, and those of MacManus or Macmaras at Santwat (Santroust or Sandwath). Accounts indicate that the fight was long and sanguine, with heavy losses on both sides. The followers of MacManus were winning when the women of the north rallied their menfolk who then reversed the course of the battle. Óttar's army won the battle, but he was killed along with MacManus.[11][12] Jarl Óttar was the father, or possibly grandfather, of Óttar of Dublin.[13]

Óttar, King of Dublin

Óttar (in Irish Oitir Mac mic Oitir) was from the Norse-Gaelic territory of the Western Isles of Scotland; he seized control of the Kingdom of Dublin in 1142. Following his take over of Dublin he "...burned the cathedral of Kells, and plundered that town."[14] This most likely refers to the Church at Kells in County Meath.

According to several versions of the Brut y Tywysogion an Óttar based in Dublin, and described as the "son of the other Óttar," was active fighting as a mercenary in Wales in 1144.[15] Contemporary annals suggest that Óttar was co-king with Ragnall mac Torcaill, until Ragnall was killed in a battle against the forces of Midhe (Meath) in 1145 or 1146.[16] Óttar retained control of Dublin until 1148 when he was "treacherously killed" by Ragnall's kin, the Meic Torcaill.[17]

Thorfinus filius Oter

Óttar of Dublin's son Thorfin was described as the most powerful princeps (jarl) of the Hebrides.[18] Thorfin was instrumental in the replacement of Godred II Olafsson as the major power in the Hebrides by Dubgall the son of Somerled. He conducted Dubgall throughout the isles compelling many local chieftains to acknowledge his authority and render hostages (1154–1155). It has been claimed that Thorfin was acting out a blood feud as Godred had played a part in instigating Óttar's murder; Godred is recorded in some sources as ruling Dublin for a short period after Óttar's death.[19][20] The historian Gareth Williams has postulated a kinship link between the mother of Dubgall, Ragnhildis Ólafsdóttir, and the Óttar family which may also have affected Thorfin's political inclinations.[21]

Therulfe MacCotter

Therulfe was the son of Thorfin and grandson of Óttar of Dublin. Following the fall of the Kingdom of Dublin, and a considerable part of the rest of Ireland, to the Anglo-Norman invasion Therulfe took part in an expedition, consisting of 35 ships, mounted by the Ostmen of Cork in 1173 or 1174 against the Normans under Adam de Hereford, deputy to Raymond le Gros. The expedition was defeated in a naval battle at Dungarvan or Youghal, the Ostmen attacked using axes and slingshot, the Normans replied with bows and crossbows. The leader of the Men of Cork, named 'Gileberti filii Turgarii', was killed. With the remnants of the fleet Therulfe returned to Cork, where he settled. In Cork he married a woman named Joane or Johanna le Fleming, described as a "foreign lady."[22][23]

Though the two Óttars and Thorfin are attested historical figures, and a considerable amount of circumstantial evidence suggests that they belong to the same family, their precise father-son relationships and also their ancestry of Therulfe are unambiguously stated only in a lost manuscript once belonging to the Cotter family of Cork. The document was discovered at Rockforest following the death of Sir James Cotter the second baronet in 1829.[24] Though the original manuscript subsequently disappeared, some of the information from it survived in a digest compiled by the Reverend Charles P. Cotter which was eventually published in the Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society by G. de P. Cotter in 1938.

Cotters outside Ireland

Murdo MacCotter

Possible evidence that the Cotter family maintained "foreign" interests may be the presence in the 15th century of one Murdo MacCotter in Orkney, fighting under the head of Clan MacLeod of Harris. According to the account he actually slew the Earl of Orkney in single combat,[25][26] although it is unclear which one this might have been. Presumably this was a raiding party launched from the Hebrides. Murdo MacCotter later became the ensignbearer for the head of Clan Maclean. It is unknown if he belonged to the MacCotters of County Cork or perhaps belonged to a related sept based elsewhere.

Isle of Man

The MacCotters appear to have retained a presence on the Isle of Man long after the end of Norse rule there. Here the surname eventually came to be spelled Cottier.[27] This must be distinguished from the identical looking English surname Cottier. The Manx MacCotters are said to descend from a brother of Óttar of Dublin named Acon or Haro (presumably the Norse name Hakon or similar was intended), who was born on the island.[28]

Presence in Dublin and Meath

The Cotters of County Cork

Maurice Makotere "from the world's end"

Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the remaining Norse-Gaelic, also known as 'Ostmen,' families of Ireland were in extremely desperate circumstances as they did not have the countryside available to them to the same degree as the Gaelic Irish. This lack of a hinterland to withdraw into forced the Ostmen to fully accommodate the new Anglo-Norman power. In 1290 one Maurice Makotere (Mac Coitir), probably of County Cork, protested to the new authorities on behalf of 300 of his kinsfolk, that they were being treated like the Irish but were in fact "not Irish", and had actually paid £3000, an extraordinary sum at the time, to gain the rights of Englishmen. Edward I of England then decreed that Maurice Makotere was "a pure Englishman", like his ancestors, and was entitled to his rights.[29] While of course he and his kin were not English this was meant for the understanding of the authorities.

According to Maurice Makotere in 1290, he wrote "from the world's end" (there is a place called World's End in Kinsale, Cork - historically it had an Irish name of the same meaning).

In time the Anglo-Norman families, such as the Fitzgeralds and Burkes, became thoroughly Gaelicised in culture. This process also happened to the Mac Cotters, in later years the Cotters produced a number of notable poets and writers in Irish, and their chieftains were amongst the last to remain patrons of Gaelic literature.

Two branches

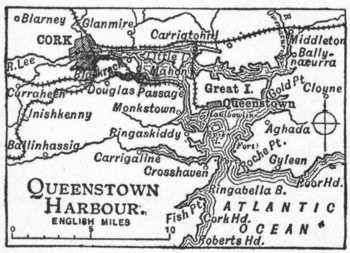

From the late 15th century, if not earlier, two main branches of the Cotter family in County Cork are evident, one based at Coppingerstown Castle, the other at Inismore (Great Island, Oileán Mór an Barraigh, on which the port of Cobh, formerly Queenstown, stands). The family name was usually recorded as 'MacCotter' until the 17th century when the form 'Cotter' becomes almost universal. However, in writings using the Irish language (Gaelic) the name remained Mac Coitir.[30] A number of placenames in East Cork, including Ballymacotters and Scartmacotters, attest to the presence of the Cotter family from an early date. There is evidence, as is found in some other Irish septs, that branches of the Cotter family were demarcated by colour, the Inismore Cotters were the 'Yellow Cotters' (Mac Coitir Buidhe) and other Cotters (possibly those based at Coppingerstown) were the 'Red Cotters' (Mac Coitir Ruadh)

The Cotters of Coppingerstown

"In 1585 John Cotter, of Coppingerstown, having land to the amount of 174 acres, made it over to his son, on condition that he should divide and share it with his cousins after the manner of their predecessors." The Coppingerstown Cotters, which tradition considers the senior branch, were connected by marriage to the de Barry family as there is a record of Margaret, daughter of James Murtagh Barry, as wife of William Shaine MacCotter, of Ballycopiner (Coppingerstown). During the Commonwealth period in the mid 17th century the head of the Coppingerstown Cotters was William, son of Edmond, whose principal residence was Coppingerstown Castle. He forfeited his lands, possibly including land in Imokilly, Ballinsperrig and Scarth MacCotter (Scartmacotters), under attainder as a result of his taking part in the Irish War of 1641 (or Irish Rebellion of 1641) on the side of the Catholic-dominated Confederation of Kilkenny. William is recorded in the list of "Forfeiting Proprietors in Ireland, under the Cromwellian Settlement."[31][32]

The Cotters of Inismore and Anngrove

The ancestry of this branch is more fully documented, the earliest recorded member is a William Cottyr who flourished during the reign of King Edward IV (1461–1483). His direct descendant was Edmond Fitz Garret Cotter (whose mother was another member of the de Barry family), a contemporary of the William Cotter who lost his lands around Coppingerstown and Imokilly. Edmond held considerable lands in Inismore and at Ballinsperrig (later renamed Anngrove), where his principal residence was. Large areas of Inismore seem to have been held by the Cotter family from 1572 at the latest, when Edmond Buidhe and William Óg MacCoter are mentioned in a deed.[33][34] Edmond Fitz Garret also held lands in Lacken, and by 1656 apparently held all of Inismore Island.[35] In sharp contrast to the fate of the Coppingerstown Cotters the family of Edmond Cotter of Anngrove survived the chaotic times from 1641 until the crushing of Irish resistance by Oliver Cromwell, and the renewed influx of Protestant planters, with increased prosperity and landholdings. Edmond Cotter married twice and had a large number of children. This probably diluted the inheritance of his second son, and most prominent member of the Cotter family in the Early Modern period, James Fitz Edmond Cotter, and explains why he embarked on his remarkable career.

Sir James Fitz Edmond Cotter

Born around 1630, James Cotter attached himself to the Royalist cause in the Civil Wars. On the restoration of Charles II to the throne in 1660 he was a lieutenant in a foot (infantry) regiment.[36] James Cotter founded his career in royal service by organising and executing the assassination of one of the regicides (people involved in the trial and execution of Charles I), John Lisle, in Switzerland (at Lausanne, 14 September 1664).[37] In 1666 he went to the West Indies. In 1667 he commanded 700 men in an attack on St Christopher's when he was captured by the French. In 1681 he was appointed Governor of the island of Montserrat.[38] With a royal pension and his profits from his West Indian governorship James Cotter became very wealthy. It is likely that James Cotter was an intimate of James II and may have served at sea with the king when he was Duke of York, and an admiral, in the war against the Dutch of 1665. James Cotter is believed to have been knighted by King James in 1685 following the Battle of Sedgemoor.[39] James II had converted to Roman Catholicism before he succeeded to the throne, the birth of a son an heir who would be raised a Catholic precipitated the Glorious Revolution of 1688, and James fled England. In order to retrieve his fortunes King James landed in Ireland in March 1689 with French troops. At this time Sir James Cotter, a Catholic like his king, was made commander of the Jacobite forces in Cork. In 1691 Cotter was made Brigadier General in command of all the Jacobite forces in counties Cork, Kerry, Limerick and Tipperary.[40] During the time of his authority Sir James Cotter treated the Protestant landowners well. He was rewarded for his moderation when, following the surrender of the Jacobite forces under the Treaty of Limerick, the support of his Protestant neighbours allowed him to retain his property and lands in full.[41]

Sir James Cotter was, in the style of previous generations of Irish chieftains, a great patron of poetry and other writings in the Irish language. Domhnall Ó Colmáin included much biographical material concerning Sir James in his tract Párliament na mBan.

James Fitz Edmond Cotter married twice (the first marriage without issue), his second wife being Ellen Plunkett daughter of Matthew, 7th Lord Louth. He died in 1705. His eldest son, James, inherited his wealth and patronage of the Catholic population of Cork, but not his astute political instincts and ended his life on the gallows.[42]

James Cotter the Younger

James Cotter the Younger (Séamus Óg Mac Coitir) was the victim of a celebrated case of judicial murder and was executed in Cork City in 1720. He was the elder son of Sir James Fitz Edmond Cotter. Like his father he exhibited overt Jacobite sympathies and was considered as the natural leader of the Catholic community of Cork City and of County Cork generally. News of his execution sparked a wave of rioting on a national scale. His death also provided the subject of many poems in Irish.[43]

Cotter Baronets, of Rockforest (1763)

The Cotter Baronetcy, of Rockforest in the County of Cork, is a title in the Baronetage of Ireland. It was created on 11 August 1763 for James Cotter,[44] Member of the Irish House of Commons for Askeaton. He was the son of the executed James Cotter the Younger. The authorities intervened in the education of the first baronet and his siblings who were raised as Protestants.[45] This act eliminated one of the families who formed the hereditary leadership of the Catholic community in Ireland. Ultimately, the descendants of Sir James Fitz Edmond Cotter retained their wealth and political prominence, but at the cost of losing the faith and culture their ancestors long upheld. The first baronet's grandson, the third baronet (who succeeded his father), represented Mallow in the British House of Commons.[46] The latter's great-grandson (the title having descended from father to son except for the fourth baronet who was succeeded by his grandson), the sixth baronet, was a Lieutenant-Colonel in the 13th/18th Regiment of the Royal Hussars and fought in the Second World War, where he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order. As of 2008 the title is held by the sixth baronet's nephew, the seventh baronet, who succeeded his uncle in 2001. He is the son of Laurence Stopford Llewellyn Cotter, younger son of the fifth baronet. Heir apparent, Julius Cotter.

- Sir James Cotter, 1st Baronet (c. 1714-1770)

- Sir James Laurence Cotter, 2nd Baronet (c. 1748-1829)

- Sir James Laurence Cotter, 3rd Baronet (c. 1787-1834)

- Sir James Laurence Cotter, 4th Baronet (1828–1902)

- Sir James Laurence Cotter, 5th Baronet (1887–1924)

- Sir Delaval James Alfred Cotter, 6th Baronet (1911–2001)

- Sir Patrick Laurence Delaval Cotter, 7th Baronet (b. 1941)

Notes

- Ó Murchadha, pp. 261–4

- Ó Murchadha, p. 261

- E. Kock, E. in Den Norsk-Isldndska Skaldediktningen (2 vols., Lund, I946-50), i. 141.

- Todd, pp. 30–31

- Steenstrup, pp. 13 ff

- Todd, pp. 38–41

- Todd, pp. 34–35

- http://www.ucc.ie/chronicon/ocor2fra.htm

- Callow, Ch. V

- Chronicle of Man, Vol I, under the year 1098

- Cotter 1938, pp. 23-24.

- Callow, Ch. V.

- Williams, p. 142

- Cotter 1938, p. 24

- Williams, p. 143

- Annals of the Four Masters (M1146.3)

- Annals of Tigernach (T1148.3)

- Williams, p. 143

- Cotter 1938, p. 25

- Chronicle of Man Vol. I, under the year 1154

- Williams, whole article.

- Cotter 1938, p. 25

- Frowde, pp. 330-331

- Ó Cuív, p. 137 (footnote 6)

- MacDonald & Fergusson, p. 106

- The Celtic Magazine: History of the MacDonalds. September 1880, Volume V

- Manx Surnames

- Cotter 1938, p. 24

- Ó Murchadha, p. 262

- O'Hart, p. 618

- Coleman, pp. 1-12

- Ó Cuív, p. 138

- O'Hart, p. 618

- Coleman, p. ?

- Ó Cuív, p. 137

- Ó Cuív, p. 141

- Ó Cuív, pp. 139-143

- Ó Cuív, pp. 148-150

- Ó Cuív, pp. 154-155

- Ó Cuív, pp. 155-157

- Ó Cuív, pp. 157-158

- Ó Cuív, pp. 158-159

- Leland, p. 19.

- "No. 10308". The London Gazette. 26 April 1763. p. 5.

- Nichols, p. 121

- O'Hart, (Supplement - 2007 reprint) pp. 614-615.

References

- Primary sources

- Annals of the Four Masters, ed. & tr. John O'Donovan (1856). Annála Rioghachta Éireann. Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland by the Four Masters... with a Translation and Copious Notes. 7 vols (2nd ed.). Dublin: Royal Irish Academy. CELT editions. Full scans at Internet Archive: Vol. 1; Vol. 2; Vol. 3; Vol. 4; Vol. 5; Vol. 6; Indices.

- Annals of Ulster, ed. & tr. Seán Mac Airt and Gearóid Mac Niocaill (1983). The Annals of Ulster (to AD 1131). Dublin: DIAS. Lay summary – CELT (2008).

- Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib, ed. & tr. James Henthorn Todd (1867). Cogadh Gaedhel re Gallaibh: The War of the Gaedhil with the Gaill. London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer.

- Cotter, G. de P. (ed.), "The Cotter Family of Rockforest, Co. Cork", in Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society 43 (1938): 21–31

- Chronicle of Man

- MacDonald, Angus John and Donald A. Fergusson (eds.), The Hebridean Connection: Accounts and Stories of the Uist Sennachies. Halifax. 1984.

- Secondary sources

- Bugge, Alexander (1904), "Bidrag til det sidste Afsnit af Nordboernes Historie i Irland", in Aarbøger for nordisk oldkyndighed og historie, II. (Kongelige Nordiske oldskrift-selskab). Copenhagen: H. H. Thirles Bogtrykkeri. pp. 248–315. alternative scan

- Burke, J. (1832). A General and Heraldic Dictionary of the Peerage and Baronetage of the British Empire. Volume 1. H. Colburn and R. Bentley.

- Callow, Edward (1899) From King Orry to Queen Victoria: a Short and Concise History of the Isle of Man. Elliot Stock, London.

- Coleman, James, "Notes on the Cotter family of Rockforest, Co. Cork", in Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society XIV, Second Series (1908): 1–12.

- Frowde, Henry (1911) Ireland under the Normans 1169-1216, Oxford.

- Kidd, Charles, Williamson, David (editors). Debrett's Peerage and Baronetage (1990 edition). New York: St Martin's Press, 1990.

- Leigh Rayment's list of baronets

- Leland, M. (1999) The lie of the land: Journeys Through Literary Cork, Cork University Press. ISBN 1-85918-231-3

- Nichols, J. G. (1858) The Topographer and Genealogist Vol. III, London.

- Ó Cuív, B. (1959) James Cotter, a Seventeenth-Century Agent of the Crown. The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol. 89, No. 2 (1959), pp. 135–159.

- O'Hart, John, Irish Pedigrees. Dublin: James Duffy and Co. 5th edition, 1892. pp. 187–9

- O'Hart, John, The Irish And Anglo-Irish Landed Gentry, When Cromwell Came to Ireland: Or, a Supplement to Irish Pedigrees, Vol II, Reprinted 2007, Heritage Books.

- Ó Murchadha, Diarmuid (1996). Family Names of County Cork. Cork: The Collins Press. 2nd edition.

- Steenstrup, Johannes (1882) Normannerne, Volumes 3 and 4. Copenhagen: Forlagt af Rudolf Klein.

- Williams, Gareth, (2007) "These people were high-born and thought well of themselves" The family of Moddan of Dale, pp. 129 –152, in West over Sea, Studies in Scandinavian Sea-Borne Expansion and Settlement Before 1300 Edited by Beverley Ballin Smith, Simon Taylor and Gareth Williams. Pub. Brill, Leiden and Boston. ISBN 978-90-04-15893-1