Smallpox vaccine

The smallpox vaccine was the first vaccine to be developed against a contagious disease. In 1796, the British doctor Edward Jenner demonstrated that an infection with the relatively mild cowpox virus conferred immunity against the deadly smallpox virus. Cowpox served as a natural vaccine until the modern smallpox vaccine emerged in the 19th century. From 1958 to 1977, the World Health Organization conducted a global vaccination campaign that eradicated smallpox, making it the only human disease to be eradicated. Although routine smallpox vaccination is no longer performed on the general public, the vaccine is still being produced to guard against bioterrorism and biological warfare.

The smallpox vaccine diluent in a syringe alongside a vial of Dryvax dried smallpox vaccine | |

| Vaccine description | |

|---|---|

| Target disease | Smallpox |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | ACAM2000, Imvanex, Jynneos, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information / ACAM2000 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category | |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| DrugBank | |

The term vaccine derives from the Latin word for cow, reflecting the origins of smallpox vaccination. However, the exact origin of the smallpox vaccine is unclear. In the 20th century, the smallpox vaccine was identified as a separate viral species known as vaccinia, which was serologically distinct from cowpox. Whole genome sequencing has shown that vaccinia is 99.7% identical to horsepox, with cowpox being a close relative.

Types

Dryvax

Dryvax is a freeze-dried calf lymph smallpox vaccine. It is the world's oldest smallpox vaccine, created in the late 19th century by American Home Products, a predecessor of Wyeth. By the 1940s, Wyeth was the leading U.S. manufacturer of the vaccine and the only manufacturer by the 1960s. After world health authorities declared smallpox had been eradicated from nature in 1980, Wyeth stopped making the vaccine.[3]

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) kept a stockpile for use in case of emergency. In 2003 this supply helped contain an outbreak of monkeypox in the United States.[4] In February 2008 the CDC disposed of the last of its 12 million doses of Dryvax. Its supply is being replaced by ACAM2000,[5] a more modern product manufactured in laboratories by Acambis, a division of Sanofi Pasteur.[3][6] As of August 2014, 24 million doses of Imvamune were delivered to the U.S. Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) for use by people with weakened immune systems or atopic dermatitis.[7]

Dryvax is a live-virus preparation of vaccinia prepared from calf lymph. Trace amounts of the following antibiotics (added during processing) may be present: neomycin sulfate, chlortetracycline hydrochloride, polymyxin B sulfate, and dihydrostreptomycin sulfate.[8]

The vaccine is effective, providing successful immunogenicity in about 95% of vaccinated persons. Dryvax has serious adverse side-effects in about 1% to 2% of cases.[9]

Imvamune

| Vaccine description | |

|---|---|

| Target disease | Smallpox |

| Type | Attenuated virus |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Imvanex, Imvamune, Jynneos |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Professional Drug Facts |

| Routes of administration | subcutaneous injection |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| ChemSpider |

|

Imvanex (Modified Vaccinia Ankara – Bavarian Nordic) is a non-replicating smallpox vaccine developed and manufactured by Bavarian Nordic. It was approved in the European Union for active immunization against smallpox disease in adults in July 2013,[10] and was approved in Canada where it is marketed as Imvamune.[11][12][13] On its path for the approval in the U.S., Imvamune undergoes additional series of evaluation studies.[14][15][16]

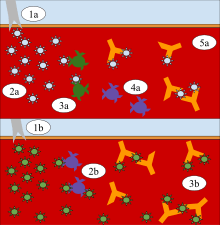

Imvanex contains a modified form of the vaccinia virus, Modified vaccinia Ankara, which does not replicate in human cells and hence does not cause the serious side effects that are seen with replicating smallpox vaccines. These replicating vaccines use different strains of the vaccinia virus, which all replicate in humans, and are not recommended for people with immune deficiencies and exfoliative skin disorders, such as eczema or atopic dermatitis. Vaccines containing vaccinia viruses were used effectively in the campaign to eradicate smallpox. Because of similarities between vaccinia and the smallpox virus, the antibodies produced against vaccinia have been shown to protect against smallpox. In contrast to replicating smallpox vaccines, which are applied by scarification using a bifurcated needle, Imvanex is administered by injection via the subcutaneous route.

The Jynneos smallpox and monkeypox live, non-replicating vaccine[17] was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in September 2019.[18] Jynneos was formerly known as MVA-BN.[7][19]

ACAM2000

ACAM2000 is a smallpox vaccine developed by Acambis. It was approved for use in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on 31 August 2007.[5] It contains live vaccinia virus, cloned from the same strain used in an earlier vaccine, Dryvax. While the Dryvax virus was cultured in the skin of calves and freeze-dried, ACAM2000s virus is cultured in kidney epithelial cells (Vero cells) from an African green monkey. Efficacy and adverse reaction incidence are similar to Dryvax.[9] The vaccine is not routinely available to the U.S. public; it is, however, used in the military and maintained in the Strategic National Stockpile.[7][20]

A droplet of ACAM2000 is administered by the percutaneous route (scarification) using 15 jabs of a bifurcated needle. ACAM2000 should not be injected by the intradermal, subcutaneous, intramuscular, or intravenous route.[21]

Calf lymph

Calf lymph was the name given[22] to a type of smallpox vaccine used in the 19th century, and which was still manufactured up to the 1970s. Calf lymph was known as early as 1805 in Italy,[23] but it was the Lyon Medical Conference of 1864 which made the technique known to the wider world.[24] In 1898 calf lymph became the standard method of vaccination for smallpox in the United Kingdom, when arm-to-arm vaccination was eventually banned[25] (due to complications such as the simultaneous transmission of syphilis).

Safety

The vaccine is infectious, which improves its effectiveness, but causes serious complications for people with impaired immune systems (for example chemotherapy and AIDS patients, and people with eczema), and is not yet considered safe for pregnant women. A woman planning on conceiving should not receive smallpox immunization. Vaccines that only contain attenuated vaccinia viruses (an attenuated virus is one in which the pathogenicity has been decreased through serial passage) have been proposed, but some researchers have questioned the possible effectiveness of such a vaccine. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), "vaccination within 3 days of exposure will prevent or significantly lessen the severity of smallpox symptoms in the vast majority of people. Vaccination 4 to 7 days after exposure likely offers some protection from disease or may modify the severity of disease." This, along with vaccinations of so-called first responders, is the current plan of action being devised by the United States Department of Homeland Security (including Federal Emergency Management Agency) in the United States.

Starting in early 2003, the United States government vaccinated 500,000 volunteer health care professionals throughout the country. Recipients were healthcare workers who would be first-line responders in the event of a bioterrorist attack. Many healthcare workers refused, worried about vaccine side effects, but many others volunteered. It is unclear how many actually received the vaccine.[26]

In May 2007, the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) voted unanimously that a new live virus vaccine produced by Acambis, ACAM2000, is both safe and effective for use in persons at high risk of exposure to smallpox virus. However, due to the high rate of serious adverse effects, the vaccine will only be made available to the CDC (a part of the United States Department of Health and Human Services) for the Strategic National Stockpile.[27]

History

Variolation

The mortality of the severe form of smallpox—variola major—was very high without vaccination, up to 35% in some outbreaks.[28] A method of inducing immunity known as inoculation, insufflation or "variolation" was practiced before the development of a modern vaccine and likely occurred in Africa and China well before the practice arrived in Europe.[29] It may also have occurred in India, but this is disputed; other investigators contend the ancient Sanskrit medical texts of India do not describe these techniques.[29][30] The first clear reference to smallpox inoculation was made by the Chinese author Wan Quan (1499–1582) in his Douzhen xinfa (痘疹心法) published in 1549.[31] Inoculation for smallpox does not appear to have been widespread in China until the reign era of the Longqing Emperor (r. 1567–1572) during the Ming Dynasty.[32] In China, powdered smallpox scabs were blown up the noses of the healthy. The patients would then develop a mild case of the disease and from then on were immune to it. The technique did have a 0.5–2.0% mortality rate, but that was considerably less than the 20–30% mortality rate of the disease itself. Two reports on the Chinese practice of inoculation were received by the Royal Society in London in 1700; one by Dr. Martin Lister who received a report by an employee of the East India Company stationed in China and another by Clopton Havers.[33] According to Voltaire (1742), the Turks derived their use of inoculation from neighbouring Circassia. Voltaire does not speculate on where the Circassians derived their technique from, though he reports that the Chinese have practiced it "these hundred years".[34]

Variolation was also practiced throughout the latter half of the 17th century by physicians in Turkey, Persia, and Africa. In 1714 and 1716, two reports of the Ottoman Empire Turkish method of inoculation were made to the Royal Society in England, by Emmanuel Timoni, a doctor affiliated with the British Embassy in Constantinople,[35] and Giacomo Pylarini. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, wife of the British ambassador to Ottoman Constantinople, is widely credited with introducing the process to Great Britain in 1721. Source material tells us on Montagu; "When Lady Mary was in the Ottoman Empire, she discovered the local practice of inoculation against smallpox called variolation."[36] In 1718 she had her son, aged five variolated. He recovered quickly. She returned to London and had her daughter variolated in 1721 by Charles Maitland, during an epidemic of smallpox. This encouraged the British Royal Family to take an interest and a trial of variolation was carried out on prisoners in Newgate Prison. This was successful and in 1722 Caroline of Ansbach, the Princess of Wales, allowed Maitland to vaccinate her children.[37] The success of these variolations assured the British people that the procedure was safe.[35]

—Dr. Peter Kennedy

Stimulated by a severe epidemic, variolation was first employed in North America in 1721. The practice had been known in Boston since 1706, when Cotton Mather (of Salem witch trial fame) discovered his slave, Onesimus had been inoculated while still in Africa, and many slaves kidnapped in Africa and brought to Boston had also received inoculations.[39] The practice was, at first, widely criticized.[40] However, a limited trial showed six deaths occurred out of 244 who were variolated (2.5%), while 844 out of 5980 died of natural disease (14%), and the process was widely adopted throughout the colonies.[41]

The inoculation technique was documented as having a mortality rate of only one in a thousand. Two years after Kennedy's description appeared, March 1718, Dr. Charles Maitland successfully inoculated the five-year-old son of the British ambassador to the Turkish court under orders from the ambassador's wife Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, who four years later introduced the practice to England.[42]

An account from letter by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu to Sarah Chiswell, dated 1 April 1717, from the Turkish Embassy describes this treatment:

The small-pox so fatal and so general amongst us is here entirely harmless by the invention of ingrafting (which is the term they give it). There is a set of old women who make it their business to perform the operation. Every autumn in the month of September, when the great heat is abated, people send to one another to know if any of their family has a mind to have the small-pox. They make parties for this purpose, and when they are met (commonly fifteen or sixteen together) the old woman comes with a nutshell full of the matter of the best sort of small-pox and asks what veins you please to have opened. She immediately rips open that you offer to her with a large needle (which gives you no more pain than a common scratch) and puts into the vein as much venom as can lye upon the head of her needle, and after binds up the little wound with a hollow bit of shell, and in this manner opens four or five veins. . . . The children or young patients play together all the rest of the day and are in perfect health till the eighth. Then the fever begins to seize them and they keep their beds two days, very seldom three. They have very rarely above twenty or thirty in their faces, which never mark, and in eight days time they are as well as before the illness. . . . There is no example of any one that has died in it, and you may believe I am very well satisfied of the safety of the experiment since I intend to try it on my dear little son. I am patriot enough to take pains to bring this useful invention into fashion in England, and I should not fail to write to some of our doctors very particularly about it if I knew any one of them that I thought had virtue enough to destroy such a considerable branch of their revenue for the good of mankind, but that distemper is too beneficial to them not to expose to all their resentment the hardy wight that should undertake to put an end to it. Perhaps if I live to return I may, however, have courage to war with them.[43]

Early vaccination

In the early empirical days of vaccination, before Pasteur's work on establishing the germ theory and Lister's on antisepsis and asepsis, there was considerable cross-infection. William Woodville, one of the early vaccinators and director of the London Smallpox Hospital is thought to have contaminated the cowpox matter—the vaccine—with smallpox matter and this essentially produced variolation. Other vaccine material was not reliably derived from cowpox, but from other skin eruptions of cattle.[44] In modern times, an effective scientific model and controlled production were important in reducing these causes of apparent failure or iatrogenic illness.

During the earlier days of empirical experimentation in 1758, American Calvinist Jonathan Edwards died from a smallpox inoculation. Some of the earliest statistical and epidemiological studies were performed by James Jurin in 1727 and Daniel Bernoulli in 1766.[45] In 1768 Dr John Fewster reported that variolation induced no reaction in persons who had had cowpox.[46] Fewster was a contemporary and friend of Jenner. Dr. Rolph, another Gloucestershire physician, stated that all experienced physicians of the time were aware of this.

Edward Jenner was born in Berkeley, England. At the age of 13, he was apprenticed to apothecary Daniel Ludlow and later surgeon George Hardwick in nearby Sodbury. He observed that people who caught cowpox while working with cattle were known not to catch smallpox. Jenner assumed a causal connection but the idea was not taken up at that time. From 1770 to 1772 Jenner received advanced training in London at St Georges Hospital and as the private pupil of John Hunter, then returned to set up practice in Berkeley.[47] When a smallpox epidemic occurred he advised the local cattle workers to be inoculated, but they told him that their previous cowpox infection would prevent smallpox. This confirmed his childhood suspicion, and he studied cowpox further, presenting a paper on it to his local medical society.

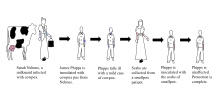

Perhaps there was already an informal public understanding of some connection between disease resistance and working with cattle. The "beautiful milkmaid" seems to have been a frequent image in the art and literature of this period. But it is known for certain that in the years following 1770, at least six people in England and Germany (Sevel, Jensen, Jesty 1774, Rendall, Plett 1791) tested successfully the possibility of using the cowpox vaccine as an immunization for smallpox in humans.[48] In 1796, Sarah Nelmes, a local milkmaid, contracted cowpox and went to Jenner for treatment. Jenner took the opportunity to test his theory. He inoculated James Phipps, the eight-year-old son of his gardener, with material taken from the cowpox lesions on Sarah's hand. After a mild fever and the expected local lesion James recovered after a few days. About two months later Jenner inoculated James on both arms with material from a case of smallpox, with no effect; the boy was immune to smallpox.

Jenner sent a paper reporting his observations to the Royal Society in April 1797. It was not submitted formally and there is no mention of it in the Society's records. Jenner had sent the paper informally to Sir Joseph Banks, the Society's president, who asked Everard Home for his views. Reviews of his rejected report, published for the first time in 1999, were skeptical and called for further vaccinations.[49] Additional vaccinations were performed and in 1798 Jenner published his work entitled An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae, a disease discovered in some of the western counties of England, particularly Gloucestershire and Known by the Name of Cow Pox.[29][50][51] It was an analysis of 23 cases including several individuals who had resisted natural exposure after previous cowpox. It is not known how many Jenner vaccinated or challenged by inoculation with smallpox virus; e.g. Case 21 included 'several children and adults'. Crucially all of at least four who Jenner deliberately inoculated with smallpox virus resisted it. These included the first and last patients in a series of arm-to-arm transfers. He concluded that cowpox inoculation was a safe alternative to smallpox inoculation, but rashly claimed that the protective effect was lifelong. This last proved to be incorrect.[52] Jenner also tried to distinguish between 'True' cowpox which produced the desired result and 'Spurious' cowpox which was ineffective and/or produced severe reaction. Modern research suggests Jenner was trying to distinguish between effects caused by what would now be recognised as noninfectious vaccine, a different virus (e.g. paravaccinia/milker's nodes), or contaminating bacterial pathogens. This caused confusion at the time, but would become important criteria in vaccine development.[53] A further source of confusion was Jenner's belief that fully effective vaccine obtained from cows originated in an equine disease, which he mistakenly referred to as grease. This was criticised at the time but vaccines derived from horsepox were soon introduced and later contributed to the complicated problem of the origin of vaccinia virus, the virus in present-day vaccine.[54]:165–178

The introduction of the vaccine to the New World took place in Trinity, Newfoundland, in 1798 by Dr. John Clinch, boyhood friend and medical colleague of Jenner.[55][56] The first smallpox vaccine in the United States was administered in 1799. The physician Valentine Seaman gave his children a smallpox vaccination using a serum acquired from Jenner.[57][58] By 1800, Jenner's work had been published in all the major European languages and had reached Benjamin Waterhouse in the United States — an indication of rapid spread and deep interest.[59] Despite some concern about the safety of vaccination the mortality using carefully selected vaccine was close to zero, and it was soon in use all over Europe and the United States.[60][61]

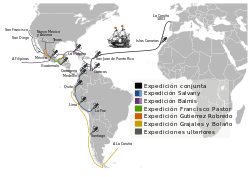

In 1804 the Balmis Expedition, an official Spanish mission commanded by Francisco Javier de Balmis, sailed to spread the vaccine throughout the Spanish Empire, first to the Canary Islands and on to Spanish Central America. While his deputy, José Salvany, took vaccine to the west and east coasts of Spanish South America, Balmis sailed to Manila in the Philippines and on to Canton and Macao on the Chinese coast. He returned to Spain in 1806.[62]

The question of who first tried cowpox inoculation/vaccination cannot be answered with certainty. Most, but still limited, information is available for Benjamin Jesty, Peter Plett and John Fewster. In 1774 Jesty, a farmer of Yetminster in Dorset, observing that the two milkmaids living with his family were immune to smallpox, inoculated his family with cowpox to protect them from smallpox. He attracted a certain amount of local criticism and ridicule at the time then interest waned. Attention was later drawn to Jesty, and he was brought to London in 1802 by critics jealous of Jenner's prominence at a time when he was applying to Parliament for financial reward.[63] During 1790–92 Peter Plett, a teacher from Holstein, reported limited results of cowpox inoculation to the Medical Faculty of the University of Kiel. However, the Faculty favoured variolation and took no action.[64] John Fewster, a surgeon friend of Jenner's from nearby Thornbury, discussed the possibility of cowpox inoculation at meetings as early as 1765. He may have done some cowpox inoculations in 1796 at about the same time that Jenner vaccinated Phipps. However, Fewster, who had a flourishing variolation practice, may have considered this option but used smallpox instead. He thought vaccination offered no advantage over variolation, but maintained friendly contact with Jenner and certainly made no claim of priority for vaccination when critics attacked Jenner's reputation.[65] It seems clear that the idea of using cowpox instead of smallpox for inoculation was considered, and actually tried in the late 18th century, and not just by the medical profession. Therefore, Jenner was not the first to try cowpox inoculation. However, he was the first to publish his evidence and distribute vaccine freely, provide information on selection of suitable material, and maintain it by arm-to-arm transfer. The authors of the official World Health Organization (WHO) account Smallpox and its Eradication assessing Jenner's role wrote:[66]

Publication of the Inquiry and the subsequent energetic promulgation by Jenner of the idea of vaccination with a virus other than variola virus constituted a watershed in the control of smallpox for which he, more than anyone else deserves the credit.

As vaccination spread, some European countries made it compulsory. Concern about its safety led to opposition and then repeal of legislation in some instances.[67][68] Compulsory infant vaccination was introduced in England by the 1853 Vaccination Act. By 1871, parents could be fined for non-compliance, and then imprisoned for non-payment.[69] This intensified opposition, and the 1898 Vaccination Act introduced a conscience clause. This allowed exemption on production of a certificate of conscientious objection signed by two magistrates. Such certificates were not always easily obtained and a further Act in 1907 allowed exemption by a statutory declaration which could not be refused. Although theoretically still compulsory, the 1907 Act effectively marked the end of compulsory infant vaccination in England.[70]

In the United States vaccination was regulated by individual states, the first to impose compulsory vaccination being Massachusetts in 1809. There then followed sequences of compulsion, opposition and repeal in various states. By 1930 Arizona, Utah, North Dakota and Minnesota prohibited compulsory vaccination, 35 states allowed regulation by local authorities, or had no legislation affecting vaccination, whilst in ten states, including Washington, D.C. and Massachusetts, infant vaccination was compulsory.[71] Compulsory infant vaccination was regulated by only allowing access to school for those who had been vaccinated.[72] Those seeking to enforce compulsory vaccination argued that the public good overrode personal freedom, a view supported by the U.S. Supreme Court in Jacobson v. Massachusetts in 1905, a landmark ruling which set a precedent for cases dealing with personal freedom and the public good.

Louis T. Wright,[73] an African-American Harvard Medical School graduate (1915), introduced intradermal vaccination for smallpox for the soldiers while serving in the Army during World War I.[74]

Developments in production

Until the end of the 19th century, vaccination was performed either directly with vaccine produced on the skin of calves or, particularly in England, with vaccine obtained from the calf but then maintained by arm-to-arm transfer;[75] initially in both cases vaccine could be dried on ivory points for short-term storage or transport but increasing use was made of glass capillary tubes for this purpose towards the end of the century.[76] During this period there were no adequate methods for assessing the safety of the vaccine and there were instances of contaminated vaccine transmitting infections such as erysipelas, tetanus, septicaemia and tuberculosis.[53] In the case of arm-to-arm transfer there was also the risk of transmitting syphilis. Although this did occur occasionally, estimated as 750 cases in 100 million vaccinations,[77] some critics of vaccination e.g. Charles Creighton believed that uncontaminated vaccine itself was a cause of syphilis.[78] Smallpox vaccine was the only vaccine available during this period, and so the determined opposition to it initiated a number of vaccine controversies that spread to other vaccines and into the 21st century.

Sydney Arthur Monckton Copeman, an English Government bacteriologist interested in smallpox vaccine investigated the effects on the bacteria in it of various treatments, including glycerine. Glycerine was sometimes used simply as a diluent by some continental vaccine producers. However, Copeman found that vaccine suspended in 50% chemically-pure glycerine and stored under controlled conditions contained very few "extraneous" bacteria and produced satisfactory vaccinations.[79] He later reported that glycerine killed the causative organisms of erysipelas and tuberculosis when they were added to the vaccine in "considerable quantity", and that his method was widely used on the continent.[75] In 1896, Copeman was asked to supply "extra good calf vaccine" to vaccinate the future Edward VIII.[80]

Vaccine produced by Copeman's method was the only type issued free to public vaccinators by the English Government Vaccine Establishment from 1899. At the same time the 1898 Vaccination Act banned arm-to-arm vaccination, thus preventing transmission of syphilis by this vaccine. However, private practitioners had to purchase vaccine from commercial producers.[81] Although proper use of glycerine reduced bacterial contamination considerably the crude starting material, scraped from the skin of infected calves, was always heavily contaminated and no vaccine was totally free from bacteria. A survey of vaccines in 1900 found wide variations in bacterial contamination. Vaccine issued by the Government Vaccine Establishment contained 5,000 bacteria per gram, while commercial vaccines contained up to 100,000 per gram.[82] The level of bacterial contamination remained unregulated until the Therapeutic Substances Act, 1925 set an upper limit of 5,000 per gram, and rejected any batch of vaccine found to contain the causative organisms of erysipelas or wound infections.[53] Unfortunately glycerolated vaccine soon lost its potency at ambient temperatures which restricted its use in tropical climates. However, it remained in use into the 1970s where a satisfactory cold chain was available. Animals continued to be widely used by vaccine producers during the smallpox eradication campaign. A WHO survey of 59 producers, some of whom used more than one source of vaccine, found that 39 used calves, 12 used sheep and 6 used water buffalo, whilst only 3 made vaccine in cell culture and 3 in embryonated hens' eggs.[83] English vaccine was occasionally made in sheep during World War I but from 1946 only sheep were used.[76]

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Leslie Collier, an English microbiologist working at the Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine, developed a method for producing a heat-stable freeze-dried vaccine in powdered form.[84][85] Collier added 0.5% phenol to the vaccine to reduce the number of bacterial contaminants but the key stage was to add 5% peptone to the liquid vaccine before it was dispensed into ampoules. This protected the virus during the freeze drying process. After drying the ampoules were sealed under nitrogen. Like other vaccines, once reconstituted it became ineffective after 1–2 days at ambient temperatures. However, the dried vaccine was 100% effective when reconstituted after 6 months storage at 37 °C (99 °F) allowing it to be transported to, and stored in, remote tropical areas. Collier's method was increasingly used and, with minor modifications, became the standard for vaccine production adopted by the WHO Smallpox Eradication Unit when it initiated its global smallpox eradication campaign in 1967, at which time 23 of 59 manufacturers were using the Lister strain.[86]

In a letter about landmarks in the history of smallpox vaccine, written to and quoted from by Derrick Baxby, Donald Henderson, chief of the Smallpox Eradication Unit from 1967–77 wrote; "Copeman and Collier made an enormous contribution for which neither, in my opinion ever received due credit".[87]

Smallpox vaccine was inoculated by scratches into the superficial layers of the skin, with a wide variety of instruments used to achieve this. They ranged from simple needles to multi-pointed and multi-bladed spring-operated instruments specifically designed for the purpose.[88]

A major contribution to smallpox vaccination was made in the 1960s by Benjamin Rubin, an American microbiologist working for Wyeth Laboratories. Based on initial tests with textile needles with the eyes cut off transversely half-way he developed the bifurcated needle. This was a sharpened two-prong fork designed to hold one dose of reconstituted freeze-dried vaccine by capillarity.[2] Easy to use with minimum training, cheap to produce ($5 per 1000), using four times less vaccine than other methods, and repeatedly re-usable after flame sterilization, it was used globally in the WHO Smallpox Eradication Campaign from 1968.[89] Rubin estimated that it was used to do 200 million vaccinations per year during the last years of the campaign.[2] Those closely involved in the campaign were awarded the "Order of the Bifurcated Needle". This, a personal initiative by Donald Henderson, was a lapel badge, designed and made by his daughter, formed from the needle shaped to form an "O". This represented "Target Zero", the objective of the campaign.[90]

Eradication of smallpox

Smallpox was eradicated by a massive international search for outbreaks, backed up with a vaccination program, starting in 1967. It was organised and co-ordinated by a World Health Organization (WHO) unit, set up and headed by Donald Henderson. The last case in the Americas occurred in 1971 (Brazil), south-east Asia (Indonesia) in 1972, and on the Indian subcontinent in 1975 (Bangladesh). After two years of intensive searches, what proved to be the last endemic case anywhere in the world occurred in Somalia, in October 1977.[91] A Global Commission for the Certification of Smallpox Eradication chaired by Frank Fenner examined the evidence from, and visited where necessary, all countries where smallpox had been endemic. In December 1979 they concluded that smallpox had been eradicated; a conclusion endorsed by the WHO General Assembly in May 1980.[92] However, even as the disease was being eradicated there still remained stocks of smallpox virus in many laboratories. Accelerated by two cases of smallpox in 1978, one fatal (Janet Parker), caused by an accidental and unexplained containment breach at a laboratory at the University of Birmingham Medical School, the WHO ensured that known stocks of smallpox virus were either destroyed or moved to safer laboratories. By 1979, only four laboratories were known to have smallpox virus. All English stocks held at St Mary's Hospital, London were transferred to more secure facilities at Porton Down and then to the U.S. at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia in 1982, and all South African stocks were destroyed in 1983. By 1984, the only known stocks were kept at the CDC in the U.S. and the State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology (VECTOR) in Koltsovo, Russia.[93] These states report that their repositories are for possible anti-bioweaponry research and insurance if some obscure reservoir of natural smallpox is discovered in the future.

Origin

The exact origin of the modern smallpox vaccine is unclear.[94] Edward Jenner had obtained his vaccine from the cow, so he named the virus vaccinia, after the Latin word for cow. Jenner believed that both cowpox and smallpox were viruses that originated in the horse and passed to the cow.[95]:52–53 Some doctors followed up on this speculation by inoculating humans with horsepox.[96] The situation was further muddied when Louis Pasteur developed techniques for creating vaccines in the laboratory in the late 19th century. As medical researchers subjected viruses to serial passage, inadequate recordkeeping resulted in the creation of laboratory strains with unclear origins.

By the early 20th century, the origins of the smallpox vaccine were hopelessly muddled. Did the vaccine originate in smallpox, horsepox, or cowpox?[97] A number of competing hypotheses existed within the medical and scientific community. Some believed that Edward Jenner's cow had been accidentally inoculated with smallpox.[98] Others believed that smallpox and vaccinia shared a common ancestor.[99]:64 In 1939, A. W. Downey showed that the vaccinia virus was serologically distinct from the "spontaneous" cowpox virus.[100] This work established vaccinia and cowpox as two separate viral species. The term vaccinia now refers only to the smallpox vaccine, while cowpox no longer has a Latin name.

The development of whole genome sequencing in the 1990s made it possible to build a phylogenetic tree of the orthopoxviruses. The vaccinia strains are most similar to each other, followed by horsepox and rabbitpox. Vaccinia's nearest cowpox relatives are the strains found in Russia, Finland, and Austria. Out of 20 cowpox strains that have been sequenced, the cowpox strains found in Great Britain are the least related to vaccinia.[101] However, the exact origin of vaccinia remains unclear. While rabbitpox is known to be a laboratory strain of vaccinia, the connection between vaccinia and horsepox is still debated. Some researchers believe that the smallpox vaccine was created from cowpox strains found in continental Europe, and horsepox is a laboratory variant of vaccinia that escaped into the wild.[94] Others believe that horsepox is the ancestral strain that evolved into vaccinia.[102][96] Since horsepox is now extinct in the wild, the origin of the smallpox vaccine may never be known.[103]

Terminology

The word "vaccine" is derived from Variolae vaccinae (i.e. smallpox of the cow), the term devised by Jenner to denote cowpox and used in the long title of his An enquiry into the causes and effects of Variolae vaccinae, known by the name of cow pox.[52] Vaccination, the term which soon replaced cowpox inoculation and vaccine inoculation, was first used in print by Jenner's friend, Richard Dunning in 1800.[47] Initially, the terms vaccine/vaccination referred only to smallpox, but in 1881 Louis Pasteur proposed that to honour Jenner the terms be widened to cover the new protective inoculations being introduced.

Vaccine stockpiles

In late 2001, the governments of the United States and the United Kingdom considered stockpiling smallpox vaccines, even while assuring the public that there was no "specific or credible" threat of bioterrorism.[104] Later, the director of State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology VECTOR warned that terrorists could easily lure underpaid former Soviet researchers to turn over samples to be used as a weapon, saying "All you need is a sick fanatic to get to a populated place. The world health system is completely unprepared for this."[105]

In the United Kingdom, controversy occurred regarding the company which had been contracted to supply the vaccine. This was because of the political connections of its owner, Paul Drayson, and questions over the choice of vaccine strain. The strain was different from that used in the United States.[106] Plans for mass vaccinations in the United States stalled as the necessity of the inoculation came into question.[107]

See also

- Kinepox

- John Clinch, first doctor to test the smallpox vaccine in North America

- Eczema vaccinatum

References

- "Smallpox vaccine Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 3 January 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- Rubin, Benjamin (1980). "A note on the development of the bifurcated needle for smallpox vaccination". WHO Chronicle. 34 (5): 180–1. PMID 7376638.

- "CDC to Destroy Oldest Smallpox Vaccine". The Associated Press. 3 March 2008. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- Anderson MG, Frenkel LD, Homann S, and Guffey J. (2003), "A case of severe monkeypox virus disease in an American child: emerging infections and changing professional values"; Pediatr Infect Dis J;22(12): 1093–1096; discussion 1096–1098.

- "ACAM2000". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 20 September 2018. STN BL 125158. Archived from the original on 17 October 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- "Safety Surveillance Study of ACAM2000 Vaccinia Vaccine - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov". clinicaltrials.gov. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- "Smallpox Vaccine Supply & Strength". National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). 26 September 2019. Archived from the original on 17 October 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- Wyeth package insert / U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- Metzger W, Mordmueller BG (2007). "Vaccines for preventing smallpox". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD004913. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004913.pub2. PMC 6532594. PMID 17636779.

- "Imvanex EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- "Smallpox vaccine: Canadian Immunization Guide". Public Health Agency of Canada. January 2014. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- "Register of Innovative Drugs" (PDF). Health Canada. June 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2020. Lay summary.

- "Products for Human Use. Submission #144762". Register of Innovative Drugs. Health Canada. Archived from the original on 17 June 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- "Infectious Diseases: Clinical Trials". Bavarian Nordic. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- "Phase II Trial to Assess Safety and Immunogenicity of Imvamune". ClinicalTrials.gov. U.S. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- Pittman, Philip (2019). "Phase 3 Efficacy Trial of Modified Vaccinia Ankara as a Vaccine against Smallpox". New England Journal of Medicine. 381 (20): 1897–1908. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1817307. PMID 31722150.

- "Jynneos". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 24 September 2019. STN 125678. Archived from the original on 17 October 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- "FDA approves first live, non-replicating vaccine to prevent smallpox and monkeypox". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 24 September 2019. Archived from the original on 17 October 2019. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- Greenberg RN, Hay CM, Stapleton JT, Marbury TC, Wagner E, Kreitmeir E, Röesch S, von Krempelhuber A, Young P, Nichols R, Meyer TP, Schmidt D, Weigl J, Virgin G, Arndtz-Wiedemann N, Chaplin P (2016). "A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase II Trial Investigating the Safety and Immunogenicity of Modified Vaccinia Ankara Smallpox Vaccine (MVA-BN) in 56-80-Year-Old Subjects". PLOS ONE. 11 (6): e0157335. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157335. PMC 4915701. PMID 27327616.

- FDA/CBER Questions and Answers; Medication Guide; accessed 1 March 2008.

- https://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/UCM142572.pdf

- BMA 1905 — for example — "Calf lymph is now available for the vaccination of every child in the country" page 21.

- Galbiati G. (1810). Memoria Sulla Inoculazione Vaccina coll'Umore Ricavato Immediatement dalla Vacca Precedentemente Inoculata. Napoli.

- Congrès Medical de Lyon (1864). "Compterendu des travaux et des discussions". Gazette Med Lyon. 19: 449–471.

- Brown, Edward (1902). The Case for vaccination. Baillière, Tindall & Cox. pp. 8, 21.

Didgeon JA (May 1963). "Development of Smallpox Vaccine in England in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries". Br Med J. 1 (5342): 1367–72. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5342.1367. PMC 2124036. PMID 20789814. - "US smallpox vaccination plan grinds to a halt". www.newscientist.com.

- "Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee Meeting". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 17 May 2007. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- Ryan KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 525–8. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- Riedel, S (January 2005). "Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination". Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center). 18 (1): 21–5. doi:10.1080/08998280.2005.11928028. PMC 1200696. PMID 16200144.

- J. Van Alphen; A. Aris (1995). "Medicine in India". Oriental Medicine: An Illustrated Guide to the Asian Arts of Healing. London: Serindia Publications. pp. 19–38. ISBN 978-0-906026-36-6.

- Needham J (1999). "Part 6, Medicine". Science and Civilization in China: Volume 6, Biology and Biological Technology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 134.

- Temple R (1986). The Genius of China: 3,000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-671-62028-8.

- Silverstein, Arthur M. (2009). A History of Immunology (2nd ed.). Academic Press. p. 293. ISBN 9780080919461..

- Voltaire (1742). "Letter XI". Letters on the English.

- Behbehani AM (1983). "The smallpox story: life and death of an old disease". Microbiol Rev. 47 (4): 455–509. doi:10.1128/MMBR.47.4.455-509.1983. PMC 281588. PMID 6319980.

- Aboul-Enein, Basil H.; Ross, Michael W.; Aboul-Enein, Faisal H. (2012). "Smallpox inoculation and the Ottoman contribution: A Brief Historiography" (PDF). Texas Public Health Journal. 64 (1): 12.

- Livingstone, N. 2015. The Mistresses of Cliveden. Three centuries of scandal, power and intrigue (p. 229)

- Kennedy, Peter (1715). An Essay on External Remedies Wherein it is Considered, Whether all the curable Distempers incident to Human Bodies, may not be cured by Outward Means. London: A. Bell.

- Willoughby B (12 February 2004). "BLACK HISTORY MONTH II: Why Wasn't I Taught That?". Tolerance in the News. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- "Open Collections Program: Contagion, The Boston Smallpox Epidemic, 1721". Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- Fenner, F.; Henderson, D. A.; Arita, I.; Jezek, Z.; Ladnyi, I.D. (1988). Smallpox and Its Eradication (History of International Public Health, No. 6) (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-156110-5. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- Robertson, Patrick (1974). The book of firsts. New York: C. N. Potter : distributed by Crown Publishers. ISBN 978-0-517-51577-8.

- "Montagu, Turkish Embassy Letters". Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- "Statue of Dr Edward Jenner near the Italian Fountains, Kensington Gardens - Scenic way to South Kensington to Birkbeck - 18 August 2001 - 3 of 4 - Part of Lachlan's London, UK 2001 Web Journal - part of Lachlan Cranswick's Personal Homepage". lachlan.bluehaze.com.au. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- Blower S, Bernoulli D (2004). "An attempt at a new analysis of the mortality caused by smallpox and of the advantages of inoculation to prevent it. 1766" (PDF). Rev. Med. Virol. 14 (5): 275–88. doi:10.1002/rmv.443. PMID 15334536. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007.

- See:

- George Pearson, ed., An inquiry concerning the history of the cowpox, principally with a view to supersede and extinguish the smallpox (London, England: J. Johnson, 1798), pp. 102–104.

- L. Thurston and G. Williams (2015) "An examination of John Fewster's role in the discovery of smallpox vaccination," Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, 45 : 173-179.

- Bailey, Ian (1996). "Edward Jenner (1749–1823); naturalist, scientist, country doctor, benefactor to mankind". Journal of Medical Biography. 4 (1): 63–70. doi:10.1177/096777209600400201. PMID 11616266.

- Hammarsten, J. F.; Tattersall, W.; Hammarsten, J. E. (1979). "Who discovered smallpox vaccination? Edward Jenner or Benjamin Jesty?". Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association. 90: 44–55. ISSN 0065-7778. PMC 2279376. PMID 390826.

- Baxby, Derrick (1999). "Edward Jenner's unpublished cowpox Inquiry and the Royal Society: Everard Home's report to Sir Joseph Banks". Medical History. 43 (1): 108–110. doi:10.1017/S0025727300064747. PMC 1044113. PMID 10885136.

- Winkelstein Jr, W. (1992). "Not just a country doctor: Edward Jenner, scientist". Epidemiologic Reviews. 14: 1–15. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036081. PMID 1289108./

- Willis, N. J. (1997). "Edward Jenner and the eradication of smallpox". Scottish Medical Journal. 42 (4): 118–21. doi:10.1177/003693309704200407. PMID 9507590.

- Baxby, Derrick (1999). "Edward Jenner's Inquiry; a bicentenary analysis". Vaccine. 17 (4): 301–7. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(98)00207-2. PMID 9987167.

- Baxby, Derrick (2001). Smallpox Vaccine, Ahead of Its Time – How the Late Development of Laboratory Methods and Other Vaccines Affected the Acceptance of Smallpox Vaccine. Berkeley, UK: Jenner Museum. pp. 12–16. ISBN 978-0-9528695-1-1.

- Baxby, Derrick (1981). Jenner's smallpox vaccine; the riddle of vaccinia virus and its origin. London: Heinemann Educational Books. ISBN 0-435-54057-2.

- Piercey, Terry (August 2002). "Plaque In Memory Of Rev. John Clinch". Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- Handcock, Gordon (1996). The Story of Trinity. Trinity: The Trinity Historical Society. p. 1. ISBN 978-098100170-8.

- "First X, Then Y, Now Z : Landmark Thematic Maps - Medicine". Princeton University Library. 2012. Archived from the original on 13 September 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- Morman, Edward T. (2006). "Smallpox". In Finkelman, Paul (ed.). Encyclopedia of the New American Nation. Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 207–208.

- Hopkins 2002, p. 262–267

- Bazin, Hervé (2000). The Eradication of Smallpox. London: Academic Press. pp. 94–102. ISBN 978-0-12-083475-4.

- Rusnock, Andrea (2009). "Catching Cowpox: the early spread of smallpox vaccination". Bull. Hist. Med. 83 (1): 17–36. doi:10.1353/bhm.0.0160. PMID 19329840.

- Smith, Michael M (1970). "The 'Real Expedición Marítima de la Vacuna' in New Spain and Guatemala". Trans Amer. Phil. Soc. New Series. 64 (4): 1–74. doi:10.2307/1006158. JSTOR 1006158.

- Pead, Patrick P (2003). "Benjamin Jesty: new light in the dawn of vaccination". Lancet. 362 (9401): 2104–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15111-2. PMID 14697816.

- Plett, Peter C (2006). "Übrigen Entdecker der Kuhpockenimpfung vor Edward Jenner". Sudhoffs Arch. (in German). 90 (2): 219–32. JSTOR 20778029. PMID 17338405.

- Williams, Gareth (2010). Angel of Death; the story of smallpox. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 162–173. ISBN 978-0-230-27471-6.

- Fenner et al 1988, p. 264.

- Williams p. 236–240.

- Williamson, Stanley (2007). The Vaccination Controversy; the rise, reign and decline of compulsory vaccination. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 9781846310867.

- Williamson 2007, p. 202−213.

- Williamson 2007, p. 233–238.

- Hopkins 2002, p. 292–3.

- George, Newell A (1952). "Compulsory Smallpox Vaccination". Publ. HLTH. Rep. 67 (11): 1135–1138. doi:10.2307/4588305. JSTOR 4588305. PMC 2030845. PMID 12993980.

- "A Brief Biography of Dr. Louis T. Wright". North by South: from Charleston to Harlem, the great migration. Retrieved 23 September 2006.

- "Spotlight on Black Inventors, Scientists, and Engineers". Department of Computer Science of Georgetown University. Archived from the original on 7 September 2006. Retrieved 23 September 2006.

- Copeman, S. Monckton (1898). "The Milroy Lectures on the Natural History of Vaccinia. Lecture III. Animal Vaccination". Br. Med. J. 1 (1951): 1312–18. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.1951.1312. PMC 2411485. PMID 20757828.

- Dudgeon, J. A. (1963). "The Development of Smallpox Vaccine in England in the 18th and 19th Centuries". Br. Med. J. 1 (5342): 1367–72. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5342.1367. PMC 2124036. PMID 20789814.

- Bazin 2000 p.122.

- Creighton, Charles (1887). The Natural History of Cowpox and Vaccinal Syphilis. London: Cassell.

- Copeman, S. Monckton. (1892). "The Bacteriology of Vaccine Lymph". In C. E. Shelley (ed.). Transactions of the Seventh International Congress of Hygiene and Demography. Eyre and Spottiswoode. pp. 319–326. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- Copeman, P. W. M. (1998). "Extinction of the speckled monster celebrated in 1996". Journal of Medical Biography. 6 (1): 39–42. doi:10.1177/096777209800600108. PMID 11619875.

- Dixon, C. W. (1962). Smallpox. London: J. & A. Churchill. pp. 280–81.

- (Special Commission) (1900). "Report of the Lancet Special Commission on Glycerinated Calf Lymph Vaccines". Lancet. 155 (4000): 1227–36. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(01)96895-3.

- Fenner et al 1988, pp. 543–5.

- Collier, L H (1955). "The development of a stable smallpox vaccine". The Journal of Hygiene. 53 (1): 76–101. doi:10.1017/S002217240000053X. ISSN 0022-1724. PMC 2217800. PMID 14367805.

- "Professor Leslie Collier". The Telegraph. 22 March 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- Fenner et al 1988, pp. 545, 550.

- Baxby, Derrick (2005). "Development of a heat stable smallpox vaccine. Collier, L. J Hyg 1955. 53; 76–101". Epidemiol. Infect. 133 (Suppl. 1): S25–S27. doi:10.1017/S0950268805004280. PMID 24965243.

- Kirkup, John R (2006). The Evolution of Surgical Instruments. Novato, California: Norman Publishing. pp. 419–37. ISBN 978-0-930405-86-1.

- Fenner et al 1988, pp. 472–3, 568–72.

- Henderson, D. A. (2009). Smallpox; the death of a disease. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-1-59102-722-5.

- Fenner et al 1988 pp. 526–37.

- Fenner et al 1988 pp. 1261–2.

- Fenner et al 1988 pp. 1273–6.

- Smithson, Chad; Kampman, Samantha; Hetman, Benjamin M.; Upton, Chris (2014). "Incongruencies in Vaccinia Virus Phylogenetic Trees". Computation. 2 (4): 182–198. doi:10.3390/computation2040182.

- Jenner, Edward (1798). An Inquiry Into the Causes and Effects of the Variolæ Vaccinæ. London: Self-published.

- Esparza, José; Schrick, Livia; Damaso, Clarissa R.; Nitsche, Andreas (19 December 2017). "Equination (inoculation of horsepox): An early alternative to vaccination (inoculation of cowpox) and the potential role of horsepox virus in the origin of the smallpox vaccine". Vaccine. 35 (52): 7222–7230. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.11.003. ISSN 0264-410X. PMID 29137821.

- Taylor, H. H. (26 October 1889). "What is Vaccinia?". British Medical Journal. 2 (1504): 951–952. ISSN 0007-1447. PMC 2155820.

- Douglas, A. J. (October 1915). "An Outbreak of Cowpox". American Journal of Public Health (New York, N.Y. : 1912). 5 (10): 1036–1037. doi:10.2105/ajph.5.10.1036. ISSN 0271-4353. PMC 1286723. PMID 18009328.

- Copeman, S. Monckton (1899). Vaccination: Its Natural History and Pathology. New York: Macmillan.

- Downie, A. W. (April 1939). "The Immunological Relationship of the Virus of Spontaneous Cowpox to Vaccinia Virus". British Journal of Experimental Pathology. 20 (2): 158–176. ISSN 0007-1021. PMC 2065307.

- Carroll, Darin S.; Emerson, Ginny L.; Li, Yu; Sammons, Scott; Olson, Victoria; Frace, Michael; Nakazawa, Yoshinori; Czerny, Claus Peter; Tryland, Morten; Kolodziejek, Jolanta; Nowotny, Norbert; Olsen-Rasmussen, Melissa; Khristova, Marina; Govil, Dhwani; Karem, Kevin; Damon, Inger K.; Meyer, Hermann (8 August 2011). "Chasing Jenner's Vaccine: Revisiting Cowpox Virus Classification". PLOS ONE. 6 (8): e23086. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...623086C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023086. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3152555. PMID 21858000.

- Schrick, Livia; Tausch, Simon H.; Dabrowski, P. Wojciech; Damaso, Clarissa R.; Esparza, José; Nitsche, Andreas (12 October 2017). "An Early American Smallpox Vaccine Based on Horsepox". New England Journal of Medicine. 377 (15): 1491–1492. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1707600. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 29020595.

- Esparza, José (21 September 2013). "Has horsepox become extinct?". Veterinary Record. 173 (11): 272–273. doi:10.1136/vr.f5587. ISSN 0042-4900. PMID 24057497.

- Womack, Sara (22 October 2001). "Talks on medicines to fight bio-terrorism". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 23 November 2007.

- Aris B, Highfield R, Broughton PD (6 November 2001). "Warning of smallpox terror risk". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- Elliott, Francis (14 April 2002). "Labour claims unravel over vaccine deal". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- DeBoer, Kara (20 May 2002). "Study: Should America vaccinate?". The Michigan Daily. Retrieved 23 November 2007.

Further reading

- Metzger W, Mordmueller BG (2007). Metzger, Wolfram (ed.). "Vaccines for preventing smallpox". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD004913. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004913.pub2. PMC 6532594. PMID 17636779.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Smallpox vaccine. |

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 27 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 831–834.

- Smallpox Vaccine: Contraindications, Administration, and Adverse Reactions

- CDC Smallpox Home

- Quick Guide to Preexposure Smallpox Vaccination

- Early smallpox Vaccination Certificate Norway 1821 GG Archives. Norwegian and English Text