Isle of Arran

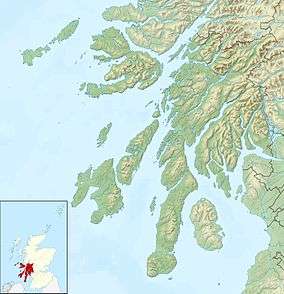

The Isle of Arran[7] (/ˈærən/; Scottish Gaelic: Eilean Arainn) or simply Arran is an island off the coast of Scotland. It is the largest island in the Firth of Clyde and the seventh largest Scottish island, at 432 square kilometres (167 sq mi). Historically part of Buteshire, it is in the unitary council area of North Ayrshire. In the 2011 census it had a resident population of 4,629. Though culturally and physically similar to the Hebrides, it is separated from them by the Kintyre peninsula. Often referred to as "Scotland in Miniature", the island is divided into highland and lowland areas by the Highland Boundary Fault and has been described as a "geologist's paradise".[8]

| Gaelic name | Eilean Arainn |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | [ˈelan ˈaɾɪɲ] ( |

| Norse name | Herrey[1] |

| Meaning of name | Possibly Brythonic for "high place" |

| Location | |

Isle of Arran Arran shown within the Firth of Clyde | |

| OS grid reference | NR950359 |

| Coordinates | 55.57°N 5.25°W |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Firth of Clyde |

| Area | 43,201 hectares (167 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 7[2] [3] |

| Highest elevation | Goat Fell 874 m (2,867 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | North Ayrshire |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 4,629[4] |

| Population rank | 6[4] [3] |

| Population density | 10.72 people/km2[4][5] |

| Largest settlement | Lamlash |

| References | [6] |

Arran has been continuously inhabited since the early Neolithic period. Numerous prehistoric remains have been found. From the 6th century onwards, Goidelic-speaking peoples from Ireland colonised it and it became a centre of religious activity. In the troubled Viking Age, Arran became the property of the Norwegian crown, until formally absorbed by the kingdom of Scotland in the 13th century. The 19th-century "clearances" led to significant depopulation and the end of the Gaelic language and way of life. The economy and population have recovered in recent years, the main industry being tourism. There is a diversity of wildlife, including three species of tree endemic to the area.

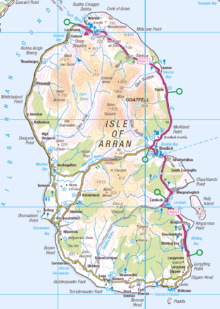

The island includes miles of coastal pathways, numerous hills and mountains, forested areas, rivers, small lochs and beaches. Its main beaches are at Brodick, Whiting Bay, Kildonan, Sannox and Blackwaterfoot.

Etymology

Most of the islands of Scotland have been occupied consecutively by speakers of at least four languages since the Iron Age. Many of the names of these islands have more than one possible meaning as a result. Arran is therefore not unusual in that the derivation of the name is far from clear. Mac an Tàilleir (2003) states that "it is said to be unrelated to the name Aran in Ireland" (which means "kidney-shaped", cf Irish ára "kidney").[9] Unusually for a Scottish island, Haswell-Smith (2004) and William Cook Mackenzie (1931) offer a Brythonic derivation and a meaning of "high place" (c.f. Middle Welsh aran) which at least corresponds with the geography — Arran is significantly loftier than all the land that immediately surrounds it along the shores of the Firth of Clyde.[8][10]

Any other Brythonic place-names that may have existed, save perhaps for Mayish,[11] were later replaced on Arran as the Goidelic-speaking Gaels spread from Ireland, via their adjacent kingdom of Dál Riata. During the Viking Age it became, along with most Scottish islands, the property of the Norwegian crown, at which time it may have been known as "Herrey" or "Hersey". As a result of this Norse influence, many current place-names on Arran are of Viking origin.[12]

Geography

The island lies in the Firth of Clyde between Ayr and Ardrossan, and Kintyre. The profile of the north Arran hills as seen from the Ayrshire coast is referred to as the "Sleeping Warrior", due to its resemblance to a resting human figure.[13][14] The highest of these hills is Goat Fell at 873.5 metres (2,866 ft).[15] There are three other Corbetts, all in the north east: Caisteal Abhail, Cìr Mhòr and Beinn Tarsuinn. Beinn Bharrain is the highest peak in the north west at 721 metres (2,365 ft).[16]

The largest glen on the island is Glen Iorsa to the west, whilst narrow Glen Sannox (Gaelic: Gleann Shannaig) and Glen Rosa (Gaelic: Gleann Ròsa) to the east surround Goat Fell. The terrain to the south is less mountainous, although a considerable portion of the interior lies above 350 metres (1,150 ft), and A' Chruach reaches 512 metres (1,680 ft) at its summit.[17][18] There are two other Marilyns in the south, Tighvein and Mullach Mòr (Holy Island).

Villages

Arran has several villages, mainly around the shoreline. Brodick (Old Norse: 'broad bay') is the site of the ferry terminal, several hotels, and the majority of shops. Brodick Castle is a seat of the Dukes of Hamilton. Lamlash, however, is the largest village on the island and in 2001 had a population of 1,010 compared to 621 for Brodick.[19] Other villages include Lochranza and Catacol in the north, Corrie in the north east, Blackwaterfoot and Kilmory in the south west, Kildonan in the south and Whiting Bay in the south east.

Surrounding islands

Arran has three smaller satellite islands: Holy Island lies to the east opposite Lamlash, Pladda is located off Arran's south coast and tiny Hamilton Isle lies just off Clauchlands Point 1.2 kilometres (0.75 mi) north of Holy Island. Eilean na h-Àirde Bàine off the south west of Arran at Corriecravie is a skerry connected to Arran at low tide.

Other islands in the Firth of Clyde include Bute, Great Cumbrae and Inchmarnock.

Geology

The division between the "Highland" and "Lowland" areas of Arran is marked by the Highland Boundary Fault which runs north east to south west across Scotland.[20] Arran is a popular destination for geologists, who come to see intrusive igneous landforms such as sills and dykes, and sedimentary and meta-sedimentary rocks ranging in age from Precambrian to Mesozoic.

Most of the interior of the northern half of the island is taken up by a large granite batholith that was created by substantial magmatic activity around 58 million years ago in the Paleogene period.[21] This comprises an outer ring of coarse granite and an inner core of finer grained granite, which was intruded later. This granite was intruded into the Late Proterozoic to Cambrian metasediments of the Dalradian Supergroup. Other Paleogene igneous rocks on Arran include extensive felsic and composite sills in the south of the island, and the central ring complex, an eroded caldera system surrounded by a near-continuous ring of granitic rocks.[22]

Sedimentary rocks dominate the southern half of the island, especially Old and New Red Sandstone. Some of these sandstones contain fulgurites – pitted marks that may have been created by Permian lightning strikes.[20] Large aeolian sand dunes are preserved in Permian sandstones near Brodick, showing the presence of an ancient desert. Within the central complex are subsided blocks of Triassic sandstone and marl, Jurassic shale, and even a rare example of Cretaceous chalk.[23][24] During the 19th century barytes was mined near Sannox. First discovered in 1840, nearly 5,000 tons were produced between 1853 and 1862. The mine was closed by the 11th Duke of Hamilton on the grounds that it "spoiled the solemn grandeur of the scene" but was reopened after the First World War and operated until 1938 when the vein ran out.[25]

Visiting in 1787, the geologist James Hutton found his first example of an unconformity to the north of Newton Point near Lochranza, which provided evidence for his Plutonist theories of uniformitarianism and about the age of the Earth. This spot is one of the most famous places in the study of geology.[26][27]

The Pleistocene glaciations almost entirely covered Scotland in ice, and Arran's highest peaks may have been nunataks at this time.[20] After the last retreat of the ice at the close of the Pleistocene epoch sea levels were up to 70 metres (230 ft) lower than at present and it is likely that circa 14,000 BP the island was connected to mainland Scotland.[28] Sea level changes and the isostatic rise of land makes charting post-glacial coastlines a complex task, but it is evident that the island is ringed by post glacial raised beaches.[29] King's Cave on the south west coast is an example of an emergent landform on such a raised beach. This cave, which is over 30.5 metres (100 ft) long and up to 15.3 metres (50 ft) high, lies well above the present day sea level.[30][31][32] There are tall sea cliffs to the north east including large rock slides under the heights of Torr Reamhar, Torr Meadhonach and at Scriden (An Scriodan) at the far north end of the island.[18][33][34]

Climate

The influence of the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf Stream create a mild oceanic climate. Temperatures are generally cool, averaging about 6 °C (43 °F) in January and 16 °C (61 °F) in July at sea level.[35] The southern half of the island, being less mountainous, has a more favourable climate than the north, and the east coast is more sheltered from the prevailing winds than the west and south.

Snow seldom lies at sea level and frosts are less frequent than on the mainland. As in most islands of the west coast of Scotland, annual rainfall is generally high at between 1,500 mm (59 in) in the south and west and 1,900 mm (75 in) in the north and east. The mountains are wetter still with the summits receiving over 2,550 mm (100 in) annually. May and June are the sunniest months, with upwards of 200 hours of bright sunshine being recorded on average.[35]

History

Prehistory

Arran has a particular concentration of early Neolithic Clyde Cairns, a form of Gallery grave. The typical style of these is a rectangular or trapezoidal stone and earth mound that encloses a chamber lined with larger stone slabs. Pottery and bone fragments found inside them suggest they were used for interment and some have forecourts, which may have been an area for public display or ritual. There are two good examples in Monamore Glen west of the village of Lamlash,[36] and similar structures called the Giants' Graves above Whiting Bay. There are numerous standing stones dating from prehistoric times, including six stone circles on Machrie Moor (Gaelic: Am Machaire).[37]

Pitchstone deposits on the island were used locally for making various items in the Mesolithic era.[38] In the Neolithic and the Early Bronze Age pitchstone from the Isle of Arran or items made from it were transported around Britain.[38]

Several Bronze Age sites have been excavated, including Ossian's Mound near Clachaig and a cairn near Blackwaterfoot that produced a bronze dagger and a gold fillet.[39] Torr a' Chaisteal Dun in the south west near Sliddery is the ruin of an Iron Age fortified structure dating from about AD 200. The original walls would have been 3 metres (9.8 ft) or more thick and enclosed a circular area about 14 metres (46 ft) in diameter.[40]

In 2019, a Lidar survey reveals 1,000 ancient sites in Arran including a cursus.[41]

Gaels, Vikings and Middle Ages

An ancient Irish poem called Agalllamh na Senorach, first recorded in the 13th century, describes the attractions of the island.

Arran of the many stags

The sea strikes against her shoulders,

Companies of men can feed there,

Blue spears are reddened among her boulders.

Merry hinds are on her hills,

Juicy berries are there for food,

Refreshing water in her streams,

Nuts in plenty in the wood.[42]

The monastery of Aileach founded by St. Brendan in the 6th century may have been on Arran and St. Molaise was also active, with Holy Isle being a centre of Brendan's activities.[43] The caves below Keil Point (Gaelic: Rubha na Cille) contain a slab which may have been an ancient altar. This stone has two petrosomatoglyphs on it, the prints of two right feet, said to be of Saint Columba.[44]

In the 11th century Arran became part of the Sodor (Old Norse: 'Suðr-eyjar'), or South Isles of the Kingdom of Mann and the Isles, but on the death of Godred Crovan in 1095 all the isles came under the direct rule of Magnus III of Norway. Lagman (1103–1104) restored local rule. After the death of Somerled in 1164, Arran and Bute were ruled by his son Angus.[45] In 1237, the Scottish isles broke away completely from the Isle of Man and became an independent kingdom. After the indecisive Battle of Largs between the kingdoms of Norway and Scotland in 1263, Haakon Haakonsson, King of Norway reclaimed Norwegian lordship over the "provinces" of the west. Arriving at Mull, he rewarded a number of his Norse-Gaelic vassals with grants of lands. Bute was given to Ruadhri and Arran to Murchad MacSween.[Note 1] Following Haakon's death later that year Norway ceded the islands of western Scotland to the Scottish crown in 1266 by the Treaty of Perth. A substantial Viking grave has been discovered near King's Cross south of Lamlash, containing whalebone, iron rivets and nails, fragments of bronze and a 9th-century bronze coin, and another grave of similar date nearby yielded a sword and shield.[47][48] Arran was also part of the medieval Bishopric of Sodor and Man.

On the opposite side of the island near Blackwaterfoot is the King's Cave (see above), where Robert the Bruce is said to have taken shelter in the 14th century.[49] Bruce returned to the island in 1326, having earlier granted lands to Fergus MacLouis for assistance rendered during his time of concealment there. Brodick Castle played a prominent part in the island's medieval history. Probably dating from the 13th century, it was captured by English forces during the Wars of Independence before being taken back by Scottish troops in 1307. It was badly damaged by action from English ships in 1406 and sustained an attack by John of Islay, the Lord of the Isles in 1455. Originally a seat of the Clan Stewart of Menteith it passed to the Boyd family in the 15th century.[50][51] For a short time during the reign of King James V in the 16th century, the Isle of Arran was under the regency of Robert Maxwell, 5th Lord Maxwell.[52]

Modern era

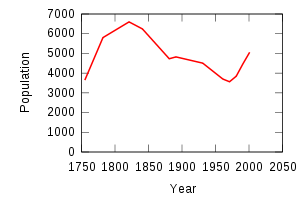

At the commencement of the Early modern period James, 2nd Lord Hamilton became a privy counsellor to his first cousin, James IV of Scotland and helped to arrange his marriage to Princess Margaret Tudor of England. As a reward he was created Earl of Arran in 1503. The local economy for much of this period was based on the run rig system, the basic crops being oats, barley and potatoes. The population slowly grew to about 6,500. In the early 19th century Alexander, 10th Duke of Hamilton (1767–1852) embarked on a programme of clearances that had a devastating effect on the island's population. These "improvements" typically led to land that had been rented out to as many as 27 families being converted into a single farm. In some cases, land was promised in Canada for each adult emigrant male. In April 1829, for example, 86 islanders boarded the brig Caledonia for the two-month journey, half their fares being paid for by the Duke. However, on arrival in Quebec only 41 hectares (100 acres) was made available to the heads of extended families. Whole villages were removed and the Gaelic culture of the island devastated. The writer James Hogg wrote, "Ah! Wae's [Woe is] me. I hear the Duke of Hamilton's crofters are a'gaun away, man and mother's son, frae the Isle o' Arran. Pity on us!".[53] A memorial to this has been constructed on the shore at Lamlash, paid for by a Canadian descendant of the emigrants.[54][55]

Goatfell was the scene of the death of English tourist Edwin Rose who was allegedly murdered by John Watson Laurie in 1889 on the mountain. Laurie was sentenced to death, later commuted to a life sentence and spent the rest of his life in prison.[56]

On 10 August 1941 a RAF Consolidated B-24 Liberator LB-30A AM261 was flying from RAF Heathfield in Ayrshire to Gander International Airport in Canada. However, the B-24 crashed into the hillside of Mullach Buidhe north of Goat Fell, killing all 22 passengers and crew.[57]

| Year | Population[58] | Year | Population |  |

| 1755 | 3,646 | 1931 | 4,506 | |

| 1782 | 5,804 | 1961 | 3,700 | |

| 1821 | 6,600 | 1971 | 3,564 | |

| 1841 | 6,241 | 1981 | 3,845 | |

| 1881 | 4,730 | 1991 | 4,474 | |

| 1891 | 4,824 | 2001 | 5,058 | |

| 2011 | 4,629 |

Arran's resident population was 4,629 in 2011, a decline of just over 8 per cent from the 5,045 recorded in 2001,[59] against a background of Scottish island populations as a whole growing by 4 per cent to 103,702 over the same period.[60]

Gaelic

| Pronunciation | ||

|---|---|---|

| Scots Gaelic: | A’ Chruach | |

| Pronunciation: | [ə ˈxɾuəx] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Am Machaire | |

| Pronunciation: | [ə ˈmaxəɾʲə] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Arainn nan Aighean Iomadh | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈaɾɪɲ ə ˈn̪ˠajən ˈiməɣ] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Arannach | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈaɾən̪ˠəx] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Beinn Bharrain | |

| Pronunciation: | [peiɲˈvarˠɛɲ] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Beinn Bhreac | |

| Pronunciation: | [peiɲˈvɾʲɛxk] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | coinean mòr | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈkʰɔɲan ˈmoːɾ] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Eilean Arainn | |

| Pronunciation: | [elanˈaɾɪɲ] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Eilean na h-Àirde Bàine | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈelan ə ˈhaːrˠtʲə ˈpaːɲə] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Gleann Ròsa | |

| Pronunciation: | [klɛun̪ˠˈrˠɔːs̪ə] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Gleann Sgoradail | |

| Pronunciation: | [klaun̪ˠ ˈs̪kɔɾat̪al] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Gleann Shannaig | |

| Pronunciation: | [klɛun̪ˠˈhan̪ˠɛkʲ] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Rubha na Cille | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈrˠu.ə nə ˈkʲʰiʎə] ( | |

Gaelic was still spoken widely on Arran at the beginning of the 20th century. The 1901 Census reported 25–49 per cent Gaelic speakers on the eastern side of the island and 50–74 per cent on the western side of the island. By 1921 the proportion for the whole island had dropped to less than 25 per cent.[61] However, Nils Holmer quotes the Féillire (a Gaelic almanack) reporting 4,532 inhabitants on the island in 1931 with 605 Gaelic speakers, showing that Gaelic had declined to about 13 per cent of the population.[62] It continued to decline until the last native speakers of Arran Gaelic died in the 1990s. Current Gaelic speakers on Arran originate from other areas in Scotland.[63] In 2011, 2.0 per cent of Arran residents aged three and over could speak Gaelic.[64]

Arran Gaelic is reasonably well documented. Holmer carried out field work on the island in 1938, reporting Gaelic being spoken by "a fair number of old inhabitants". He interviewed 53 informants from various locations and his description of The Gaelic of Arran was published in 1957 and runs to 211 pages of phonological, grammatical and lexical information. The Survey of the Gaelic Dialects of Scotland, which collected Gaelic dialect data in Scotland between 1950 and 1963, also interviewed five native speakers of Arran Gaelic.[65]

The Arran dialect falls firmly into the southern group of Gaelic dialects (referred to as the "peripheral" dialects in Celtic studies) and thus shows:[62]

- a glottal stop replacing an Old Irish hiatus, e.g. rathad 'road' /rɛʔət̪/[62] (normally /rˠa.ət̪/)

- the dropping of /h/ between vowels e.g. athair 'father' /aəɾ/[62] (normally /ahəɾʲ/)

- the preservation of a long l, n and r, e.g. fann 'weak' /fan̪ˠː/[62] (normally /faun̪ˠ/ with diphthongisation).

The most unusual feature of Arran Gaelic is the /w/ glide after labials before a front vowel, e.g. maith 'good' /mwɛh/[62] (normally /mah/).

Mac an Tàilleir notes that the island has a poetic name Arainn nan Aighean Iomadh - "Arran of the many stags" and that a native of the island or Arainneach is also nicknamed a coinean mòr in Gaelic, meaning "big rabbit".[9] Locally, Arainn was pronounced /ɛɾɪɲ/.[62]

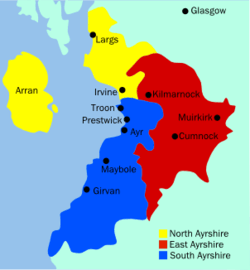

Local government

From the 17th to the late 20th century, Arran was part of the County of Bute.[66] After the 1975 reorganisation of local government Arran became part of the district of Cunninghame in Strathclyde Region.[67] This two-tier system of local government lasted until 1996 when the Local Government etc. (Scotland) Act 1994 came into effect, abolishing the regions and districts and replacing them with 32 council areas. Arran is now in the North Ayrshire council area, along with some of the other constituent islands of the County of Bute.

For some statistical purposes Arran is within the registration county of Bute,[68] and for ceremonial purposes it forms part of the lieutenancy area of Ayrshire and Arran.

In the House of Commons, since 2005 it has been part of the Ayrshire North and Arran constituency, represented since 2015 by Patricia Gibson of the SNP. It is marginal between the SNP and the Scottish Conservatives. It had been part of Cunninghame North from 1983 to 2005, and of Ayrshire North and Bute from 1918 to 1983.

In the Scottish Parliament, Arran is part of the constituency of Cunninghame North, currently represented by Kenneth Gibson of the Scottish National Party (SNP). The Labour Party held the seat until 2007, when the SNP gained it by 48 votes, making it the most marginal seat in Holyrood until 2011, when the SNP increased its majority to 6,117 over Labour.[69]

Health services

NHS Ayrshire and Arran is responsible for the provision of health services for the island. Arran War Memorial Hospital is a 17-bed acute hospital at Lamlash. The Arran Medical Group provides primary-care services and supports the hospital. The practice is based at Brodick Health Centre and has three base surgeries and four branch surgeries.[70]

Transport

Arran is connected to the Scottish mainland by two ferry routes operated by Caledonian MacBrayne. The Brodick to Ardrossan service is provided by MV Caledonian Isles, with additional summer sailings by MV Isle of Arran. A service to Lochranza is provided by MV Catriona from Claonaig in summer and from Tarbert in winter.[71] Summer day trips are also available on board the paddle steamer PS Waverley, and a summer service operated by a local resident connects Lamlash to the neighbouring Holy Island.

Brodick Ferry Terminal underwent £22 million of work to improve connections to the island. The new terminal includes better passenger facilities, increased passenger and freight capacity, and a new pier, all of which were set to open in August 2017 but finally opened on 20 March 2018, due to various construction issues. The island is due to be served by a new £45-million dual-fuelled ferry, Glen Sannox, which will have capacity for 1,000 passengers. This was due in 2018 but has also been delayed due to various construction issues and is now expected to be delivered in late 2021.[72]

There are three through roads on the island. The 90 kilometres (56 mi) coast road circumnavigates the island. In 2007, a 48 kilometres (30 mi) stretch of this road, previously designated as A841, was de-classified as a C road. Travelling south from Whiting Bay, the C147 goes round the south coast continuing north up the west coast of the island to Lochranza. At this point the road becomes the A841 down the east coast back to Whiting Bay.[73] At one point the coast road ventures inland to climb the 200 metres (660 ft) pass at the Boguillie between Creag Ghlas Laggan and Caisteal Abhail, located between Sannox and Lochranza.[18]

The other two roads run across from the east to the west side of the island. The main cross-island road is the 19 kilometres (12 mi) B880 from Brodick to Blackwaterfoot, called "The String", which climbs over Gleann an t-Suidhe. About 10 kilometres (6 mi) from Brodick, a minor road branches off to the right to Machrie. The single-track road "The Ross" runs 15 kilometres (9 mi) from Lamlash to Lagg and Sliddery via Glen Scorodale (Gaelic: Gleann Sgoradail).[74]

The island can be explored using a public bus service operated by Stagecoach.[75] The main bus terminal on the island is located in Brodick at the Ferry Terminal. The newly upgraded facility offers routes to all parts of the island.

Economy

Tourism

The main industry on the island is tourism, with outdoor activities such as walking, cycling and wildlife watching being especially popular.[76] Popular walking routes include climbing to the summit of Goat Fell, and the Arran Coastal Way, a 107 kilometre trail that goes around the coastline the island.[77][78][79] The Arran Coastal Way was designated as one of Scotland's Great Trails by Scottish Natural Heritage in June 2017.[80]

One of Arran's greatest attractions for tourists is Brodick Castle, owned by the National Trust for Scotland. The Auchrannie Resort, which contains two hotels, three restaurants, two leisure complexes and an adventure company, is one of biggest employers on the island.[81] Local businesses include the Arran Distillery, which was opened in 1995 in Lochranza. This is open for tours and contains a shop and cafe. A second visitor centre has been announced for the south of the island, due to open in 2019.

The island has a number of golf courses including the 12 hole Shiskine links course which was founded in 1896.[82] The village of Lagg, at the southern tip of Arran, has a nudist beach. Known as Cleat's Shore, it has been described as one of the quietest nudist facilities in the world.[83]

Other industries

Farming and forestry are other important industries. Plans for 2008 for a large salmon farm holding 800,000 or more fish in Lamlash Bay have been criticised by the Community of Arran Seabed Trust. They fear the facility could jeopardise Scotland's first marine No Take Zone, which was announced in September 2008.[84][85]

The Arran Brewery is a microbrewery founded in March 2000 in Cladach, near Brodick. It makes eight regular cask and bottled beers. The wheat beer, Arran Blonde (5.0% abv) is the most popular; others include Arran Dark and Arran Sunset,[86] with a seasonal Fireside Ale brewed in winter. The brewery is open for tours and tastings.[87] The business went into liquidation in May 2008,[88] but was then sold to Marketing Management Services International Ltd in June 2008. It is now back in production and the beers widely available in Scotland, including certain Aldi stores, yet cutting staff in 2017 and 2018.[89] Other businesses include Arran Aromatics, which produces a range of luxury toiletries, perfumes and candles, Arran Dairies, Arran Cheese Shop, James's Chocolates, Wooleys of Arran and Arran Energy who produce biomass wood fuels from island-grown timber.[90]

Popular Culture

The island features in The Scottish Chiefs.[91]

The Scottish Gaelic dialect of Arran died out when the last speaker Donald Craig died in the 1970s. However, there is now a Gaelic House in Brodick, set up at the end of the 1990s. Brodick Castle features on the Royal Bank of Scotland £20 note and Lochranza Castle was used as the model for the castle in The Adventures of Tintin, volume seven, The Black Island.

Arran has one newspaper, The Arran Banner. It was listed in the Guinness Book of Records in November 1984 as the "local newspaper which achieves the closest to a saturation circulation in its area". The entry reads: "The Arran Banner, founded in 1974, has a readership of more than 97 per cent in Britain's seventh largest off-shore island."[92] There is also an online monthly publication called Voice for Arran, which mainly publishes articles contributed by community members.[93]

In 2010 an "Isle of Arran" version of the game Monopoly was launched.[94]

The knitting style used to create Aran sweaters is often mistakenly associated with the Isle of Arran rather than the Irish Aran Islands.[95]

Nature and conservation

Red deer are numerous on the northern hills, and there are populations of red squirrel, badger, otter, adder and common lizard. Offshore there are harbour porpoises, basking sharks and various species of dolphin.[96]

Flora

The island has three endemic species of tree, the Arran whitebeams.[97] These trees are the Scottish or Arran whitebeam (Sorbus arranensis), the bastard mountain ash or cut-leaved whitebeam (Sorbus pseudofennica)[98] and the Catacol whitebeam (Sorbus pseudomeinichii). If rarity is measured by numbers alone they are amongst the most endangered tree species in the world. They are protected in Glen Diomhan off Glen Catacol, at the north end of the island by a partly fenced off national nature reserve, and are monitored by staff from Scottish Natural Heritage. Only 236 Sorbus pseudofennica and 283 Sorbus arranensis were recorded as mature trees in 1980.[99] They are typically trees of the mountain slopes, close to the tree line. However, they will grow at lower altitudes, and are being preserved within Brodick Country Park.

Birds

Over 250[100] species of bird have been recorded on Arran, including black guillemot, eider, peregrine falcon, golden eagle, short-eared owl, red-breasted merganser and black-throated diver. In 1981 there were 28 ptarmigan on Arran, but in 2009 it was reported that extensive surveys had been unable to record any.[101][102] However, the following year a group of 5 was reported.[103] Similarly, the red-billed chough no longer breeds on the island.[104] 108 km2 of Arran's upland areas is designated a Special Protection Area under the Natura 2000 programme due to its importance for breeding hen harriers.[105]

Marine conservation

The north of Lamlash Bay became a Marine Protected Area and No Take Zone under the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010, which means no fish or shellfish may be taken in the area.[106][107] In 2014 the Scottish Government created Scotland's first Marine Conservation Order in order to protect delicate maerl beds off south Arran, after fishermen breached a voluntary agreement not to trawl in the vicinity.[108] The sea surrounding the south of the island are now recognised as one of 31 of Mature Conservation Marine Protected Areas in Scotland. The designation is in place to the maerl beds, as well as other features including: burrowed muds; kelp, seaweed and seagrass beds; and ocean quahog.[109]

North Arran National Scenic Area

The northern part of the island is designated a national scenic area (NSA),[110] one of 40 such areas in Scotland which are defined so as to identify areas of exceptional scenery and to ensure its protection by restricting certain forms of development.[111] The North Arran NSA covers 27,304 ha in total, consisting of 20,360 ha of land and a further 6,943 ha of the surrounding sea.[112] It covers all of the island north of Brodick and Machrie Bay, as well as the main group of hills surrounding Goat Fell.[110]

Notable residents

- Sir Kenneth Calman (born 1941) – Chancellor of Glasgow University, former Scottish and UK Chief Medical Officer and author of the Calman Commission on Scottish devolution[113]

- Flora Drummond (1878–1949) – suffragette

- Lieut. Col. James Fullarton, C. B., K. H. (1782–1834) – fought at the Battle of Waterloo.

- Daniel Macmillan (1813–1857) – He and his brother Alexander founded Macmillan Publishers in 1843. His grandson was Prime Minister Harold Macmillan.

- Jack McConnell (born 1960) – First Minister of Scotland (2001–2007)

- Robert McLellan (1907–1985) – playwright and poet in Scots

- Alison Prince (1931-2019) – children's writer

- J. M. Robertson (1856–1933) – politician and journalist

See also

References

- Notes

- Murchad MacSween is called "Margad" in the original Norwegian text.[46] According to Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar, "In this expedition King Haco regained all those provinces which King Magnus Barefoot had acquired, and conquered from the Scotch and Hebrideans, as is here narrated."[47]

- Footnotes

- Downie (1933) p. 38. Downie also offers "Hersey".

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. pp. 502-03. Modified to include bridged islands. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

- Area and population ranks: there are c. 300 islands over 20 ha in extent and 93 permanently inhabited islands were listed in the 2011 census.

- National Records of Scotland (15 August 2013). "Appendix 2: Population and households on Scotland's Inhabited Islands" (PDF). Statistical Bulletin: 2011 Census: First Results on Population and Household Estimates for Scotland Release 1C (Part Two) (PDF) (Report). SG/2013/126. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p.11.

- Infobox reference is Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. pp. 11-17 unless otherwise stated. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

- "Isle of Arran". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 11–17.

- Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2003) Ainmean-àite/Placenames. (pdf) Pàrlamaid na h-Alba. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- Mackenzie, William Cook (1931). Scottish Place-names. K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Company. p. 124.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Mac an Tàilleir, Iain. "Gaelic Place Names (K-O)" (PDF). The Scottish Parliament. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- Downie (1933) pp. 38–39.

- Keay and Keay (1994) p. 42 refers to "the profile of the 'Sleeping Warrior' of Arran as seen from the Clyde Coast". Various websites claim the phrase refers to single hills, none of which individually resemble a reclining human figure.

- "Arran Page 1" hughspicer.fsnet.co.uk. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- Downie (1933) p. 2.

- Johnstone et al. (1990) pp. 223-26.

- Haswell-Smith (1994) p. 13.

- Grid reference NR988355

- "Scrol Browser" Scotland's Census Results Online. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- McKirdy et al. (2007) pp. 297- 301.

- Chambers (2000) PhD Thesis

- King, Basil Charles (1 January 1954). "The Ard Bheinn Area of the Central Igneous Complex of Arran". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society. 110 (1–4): 323–355. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1954.110.01-04.15. ISSN 0370-291X.

- King (1955) pp. 326

- The implications of this small chalk outcrop are considerable. It suggests that like much of southern England, Scotland once had considerable deposits of this material that have been subsequently eroded away, although there is no clear-cut evidence of this. See McKirdy et al. (2007) p. 298.

- Hall (2001) p. 28

- Keith Montgomery (2003). "Siccar Point and Teaching the History of Geology" (PDF). Journal of Geoscience Education. 51 (5): 500. Bibcode:2003JGeEd..51..500M. doi:10.5408/1089-9995-51.5.500. Retrieved 26 March 2008.

- "Hutton's Unconformity - Lochranza, Isle of Arran, UK - Places of Geologic Significance on Waymarking.com". Waymarking.com. Retrieved 20 October 2008. The site was not sufficiently convincing for him to publish his find until the discovery of a second site near Jedburgh.

- Murray (1973) pp. 68-69.

- McKirdy et al. (2007) p. 28.

- Andrew Rogie. "Geology of Arran". Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- Downie (1933) pp. 70-71.

- This cave is one of several associated with the legend of Robert the Bruce and the spider. See McKirdy et al. (2007) p. 301.

- "1:50000 map of Arran". Streetmap.co.uk. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- Downie (1933) p. 19 records that the Scriden rocks fell "it is said, some two hundred years ago, with a concussion that shook the earth and was heard in Bute and Argyllshire".

- "Regional mapped climate averages" Met Office. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

- Noble (2006) pp. 104–08.

- "Machrie Moor Stone Circles". Undiscovered Scotland. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- Ballin, Torben Bjarke (2015). "Arran pitchstone (Scottish volcanic glass): New dating evidence". Journal of Lithic Studies. 2 (1): 5–16. doi:10.2218/jls.v2i1.1166.

- Downie (1933) pp. 29–30.

- "Torr a' Chaisteal Dun". Undiscovered Scotland. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- "Airborne laser scan reveals Arran's 1,000 ancient sites". BBC News. 10 October 2019.

- Downie (1933) pp. 34–35.

- Downie (1933) pp. 35–37.

- Beare (1996) p. 26.

- Murray (1973) p. 167–71.

- W. D. H. Sellar, (October 1966) "The Origins and Ancestry of Somerled". The Scottish Historical Review/JSTOR. 45 No. 140, Part 2 pp. 131-32. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- Johnstone, Rev. James (1882) The Norwegian Account of Haco's Expedition Against Scotland; A.D. MCCLXIII. Chapter 20. William Brown, Edinburgh/Project Gutenberg. Originally printed 1782. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- Downie (1933) pp. 38–40.

- "King's Cave: The cave at Drummadoon". showcaves.com. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- Downie (1933) pp.42–43. He states that the 1406 attack led by the Earl of Lennox "utterly destroyed" the structure.

- Coventry (2008) pp. 53, 255 and 551.

- Taylor (1887) vol. 2, p. 3.

- Quoted by Haswell Smith (2004) p. 12.

- Mackillop, Dugald "The History of the Highland Clearances: Buteshire - Arran" electricscotland.com. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- "Lagantuine - Isle of Arran, Ayrshire UK" waymarking.com. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- Jack, Ian (29 March 2013). "It's a century since Arran was last in the news; then it was even more dramatic | Ian Jack". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- "Visits to Crash Sites in Scotland". Peak District Air Accident Research. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- Haswell Smith (2004) p. 11.

- General Register Office for Scotland (28 November 2003) Scotland's Census 2001 – Occasional Paper No 10: Statistics for Inhabited Islands. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- "Scotland's 2011 census: Island living on the rise". BBC News. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2004) 1901-2001 Gaelic in the Census (PowerPoint ) Linguae Celticae. Retrieved 1 June 2008.

- Holmer (1957) p. vii.

- Fleming, D. (2003) Occasional Paper 10 (pdf) General Register Office for Scotland. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- Scotland Census 2011, Table QS211SC

- Ó Dochartaigh (1997) p. 84-85.

- Downie (1933), p. 1, confirms this status at the publication date.

- "District: Cunninghame" Archived 6 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine. ScotlandsPlaces. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- "Land Register Counties: Operational Dates and Alphabetical List of Places in Scotland" (PDF). Registers of Scotland. 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- "2007 Election Results Analysis: Table 18" (pdf) scottish.parliament.uk. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- "Arran Medical Group". Arran Medical. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- "More about Arran". Caledonian MacBrayne. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- "Ferguson Marine update". Scottish Government. 18 December 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- "Arran coast road reclassified" Arran Coast Road. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- Downie (1933) p. 5.

- "Arran Bus Timetable 2009" (pdf) Stagecoach. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- "Arran Visitor Guide". Visit Scotland. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- "Scotland's Great Trails". Scottish Natural Heritage & Rucksack Readers. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- "Goat Fell". Walk Highlands. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- "The Route". Arran Coastal Way. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- "Arran Coastal Way recognised as one of 'Scotland's Great Trails'". Arran Coastal Way. 20 June 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- "Auchrannie Resort on the Isle of Arran" www.auchrannie.co.uk. Retrieved 1 March 2008

- "A wee history". Shiskine Golf and Tennis Club. Retrieved 28 Sept 2011.

- "Where are Scotland's best nudist beaches?" (26 July 2016) Daily Record. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- Ross, John (27 February 2008). "Fish-farm plan sparks fears for marine reserve". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- "Sun sets on fishing in island bay". BBC News. 21 September 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- "Cask Ales". Arran Brewery. Archived from the original on 21 September 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Visitor Centre & Shop". Arran Brewery. Archived from the original on 14 October 2004. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- Pearce, Daniel (9 May 2008). "Arran Brewery Company goes into administration". The Publican. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 22 May 2008.

- "Arran Brewery admits strategy mistake as profits fall". HeraldScotland. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- "Arran Energy". Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- Porter, Jane (1921). The Scottish Chiefs. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 162-164. ISBN 9780684193403.

- "Banner goes from strength to strength." (13 April 2007) arranbanner.co.uk. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- "Voice for Arran" voiceforarran.com. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- "Monopoly - Isle of Arran Edition" Archived 9 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine arranmonopoly.com Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- Morris, Johnny (17 March 2006). "Grail Trail". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 3 August 2007.

- "Arran Wildlife". arranwildlife.co.uk. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- Johnston, Ian (15 June 2007). "Trees on Arran 'are a whole new species'". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2007.

- Donald Rodger, John Stokes & James Ogilve (2006). Heritage Trees of Scotland. The tree Council. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-904853-03-2.

- Eric Bignal (1980). "The endemic whitebeams of North Arran". The Glasgow Naturalist. 20 (1): 60–64.

- "Birding on Arran". Arran Birding. Archived from the original on 28 December 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- "Iconic Birds at Risk". Sunday Herald. Glasgow. 1 February 2009. Available as Ptarmigan disappearing from southern Scotland

- Downie (1933) p. 132 includes the ptarmigan in a list of birds no longer extant on the island at that time including the red kite, hobby, white-tailed sea eagle, hen harrier and capercaillie.

- "Ptarmigan". Arran Birding. Archived from the original on 12 June 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- "A6.102a Chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax (breeding)" (pdf) JNCC. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- "Site Details for Arran Moors SPA". Scottish Natural Heritage. 2 May 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- "UK MPAs" UK MPA Centre. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- "Marine Conservation" Scottish Government. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- Weldon, Victoria (1 October 2014) "South Arran target for historic marine preservation order". The Herald. Glasgow. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- "South Arran NCMPA". Scottish Natural Heritage. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- "Map: North Arran National Scenic Area" (PDF). Scottish Natural Heritage. December 2010. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- "National Scenic Areas". Scottish Natural Heritage. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- "National Scenic Areas - Maps". SNH. 20 December 2010. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- "Sir Kenneth Calman - biography" BMA. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- General references

- Beare, Beryl (1996) Scotland. Myths & Legends. Avonmouth. Parragon. ISBN 0-7525-1694-9

- Coventry, Martin (2008) Castles of the Clans. Musselburgh. Goblinshead. ISBN 978-1-899874-36-1

- Downie, R. Angus (1933) All About Arran. Glasgow. Blackie and Son.

- Hall, Ken (2001) The Isle of Arran. Catrine. Stenlake Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84033-135-6

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004) The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh. Canongate. ISBN 1-84195-454-3

- Holmer, N. (1957) The Gaelic of Arran. Dublin. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

- Johnstone, Scott; Brown, Hamish; and Bennet, Donald (1990) The Corbetts and Other Scottish Hills. Edinburgh. Scottish Mountaineering Trust. ISBN 0-907521-29-0

- Keay, J., and Keay, J. (1994) Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland. London. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-255082-2

- McKirdy, Alan Gordon, John & Crofts, Roger (2007) Land of Mountain and Flood: The Geology and Landforms of Scotland. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-84158-357-0

- Murray, W.H. (1973) The Islands of Western Scotland. London. Eyre Methuen. SBN 413303802

- Noble, Gordon (2006) Neolithic Scotland: Timber, Stone, Earth and Fire. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-2338-8

- Ó Dochartaigh, C. (1997) Survey of the Gaelic Dialects of Scotland. Dublin. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

- Taylor, J. (1887) Great Historic Families of Scotland vol 2. London. J.S. Virtue & Co.

External links

- Map sources for Isle of Arran

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Isle of Arran. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Isle of Arran. |

- Information on the Arran Coastal Way long distance path

- Visitor's guide with news, events, transport and accommodation.

- Arran seen from space, NASA

- The Isle of Arran Heritage Museum

- The Arran Banner Arran's local newspaper