Room 40

Room 40, also known as 40 O.B. (Old Building) (officially part of NID25) was the cryptanalysis section of the British Admiralty during the First World War.

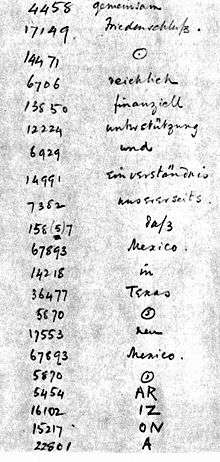

The group, which was formed in October 1914, began when Rear-Admiral Henry Oliver, the Director of Naval Intelligence, gave intercepts from the German radio station at Nauen, near Berlin, to Director of Naval Education Alfred Ewing, who constructed ciphers as a hobby. Ewing recruited civilians such as William Montgomery, a translator of theological works from German, and Nigel de Grey, a publisher. It was estimated that during the war Room 40 decrypted around 15,000 intercepted German communications from wireless and telegraph traffic.[1] Most notably the section intercepted and decoded the Zimmermann Telegram, a secret diplomatic communication issued from the German Foreign Office in January 1917 that proposed a military alliance between Germany and Mexico. Its decoding has been described as the most significant intelligence triumph for Britain during World War I[2] because it played a significant role in drawing the then-neutral United States into the conflict.[3]

Room 40 operations evolved from a captured German naval codebook, the Signalbuch der Kaiserlichen Marine (SKM), and maps (containing coded squares) that Britain's Russian allies had passed on to the Admiralty. The Russians had seized this material from the German cruiser SMS Magdeburg after it ran aground off the Estonian coast on 26 August 1914. The Russians recovered three of the four copies that the warship had carried; they retained two and passed the other to the British.[4] In October 1914 the British also obtained the Imperial German Navy's Handelsschiffsverkehrsbuch (HVB), a codebook used by German naval warships, merchantmen, naval zeppelins and U-Boats: the Royal Australian Navy seized a copy from the Australian-German steamer Hobart on 11 October. On 30 November a British trawler recovered a safe from the sunken German destroyer S-119, in which was found the Verkehrsbuch (VB), the code used by the Germans to communicate with naval attachés, embassies and warships overseas.[4] Several sources have claimed that in March 1915 a British detachment impounded the luggage of Wilhelm Wassmuss, a German agent in Persia and shipped it, unopened, to London, where the Director of Naval Intelligence, Admiral Sir William Reginald Hall discovered that it contained the German Diplomatic Code Book, Code No. 13040.[5][6] However, this story has since been debunked.[7]

The section retained "Room 40" as its informal name even though it expanded during the war and moved into other offices. Alfred Ewing directed Room 40 until May 1917, when direct control passed to Captain (later Admiral) Reginald 'Blinker' Hall, assisted by William Milbourne James.[8] Although Room 40 successfully decrypted Imperial German communications throughout the First World War, its function was compromised by the Admiralty's insistence that all decoded information would only be analysed by Naval specialists. This meant while Room 40 operators could decrypt the encoded messages they were not permitted to understand or interpret the information themselves.[9]

Background

In 1911, a sub-committee of the Committee of Imperial Defence on cable communications concluded that in the event of war with Germany, German-owned submarine cables should be destroyed. In the early hours of 5 August 1914, the cable ship Alert located and cut Germany's five trans-Atlantic cables, which ran down the English Channel. Soon after, the six cables running between Britain and Germany were cut.[10] As an immediate consequence, there was a significant increase in cable messages sent via cables belonging to other countries, and messages sent by wireless. These could now be intercepted, but codes and ciphers were naturally used to hide the meaning of the messages, and neither Britain nor Germany had any established organisations to decode and interpret the messages. At the start of the war, the navy had only one wireless station for intercepting messages, at Stockton. However, installations belonging to the Post Office and the Marconi Company, as well as private individuals who had access to radio equipment, began recording messages from Germany.[11]

Intercepted messages began to arrive at the Admiralty intelligence division, but no one knew what to do with them. Rear-Admiral Henry Oliver had been appointed Director of the Intelligence division in 1913. In August, 1914, his department was fully occupied with the war and no-one had experience of code breaking. Instead he turned to a friend, Sir Alfred Ewing, the Director of Naval Education (DNE), who previously had been a professor of engineering with a knowledge of radio communications and who he knew had an interest in ciphers. It was not felt that education would be a priority during the expected few months duration of the war, so Ewing was asked to set up a group for decoding messages. Ewing initially turned to staff of the naval colleges Osborne and Dartmouth, who were currently available, due both to the school holidays and to naval students having been sent on active duty. Alastair Denniston had been teaching German but later became second in charge of Room 40, then becoming Chief of its successor after the First World War, the Government Code and Cypher School (located at Bletchley Park during the Second World War).[12]

Others from the schools worked temporarily for Room 40 until the start of the new term at the end of September. These included Charles Godfrey, the Headmaster of Osborne (whose brother became head of naval Intelligence during the Second World War), two Naval instructors, Parish and Curtiss, and scientist and mathematician Professor Henderson from Greenwich Naval College. Volunteers had to work at code breaking alongside their normal duties, the whole organisation operating from Ewing's ordinary office where code breakers had to hide in his secretary's room whenever there were visitors concerning the ordinary duties of the DNE. Two other early recruits were R. D. Norton, who had worked for the Foreign Office, and Richard Herschell, who was a linguist, an expert on Persia and an Oxford graduate. None of the recruits knew anything about code breaking but were chosen for knowledge of German and certainty they could keep the matter secret.[12][13]

Prelude

A similar organisation had begun in the Military Intelligence department of the War Office, which become known as MI1b, and Colonel Macdonagh proposed that the two organisations should work together. Little success was achieved except to organise a system for collecting and filing messages until the French obtained copies of German military ciphers. The two organisations operated in parallel, decoding messages concerning the Western Front. A friend of Ewing's, a barrister by the name of Russell Clarke, plus a friend of his, Colonel Hippisley, approached Ewing to explain that they had been intercepting German messages. Ewing arranged for them to operate from the coastguard station at Hunstanton in Norfolk, where they were joined by another volunteer, Leslie Lambert (later becoming known as a BBC broadcaster under the name A. J. Alan). Hunstanton and Stockton formed the core of the interception service (known as 'Y' service), together with the Post Office and Marconi stations, which grew rapidly to the point it could intercept almost all official German messages. At the end of September, the volunteer schoolmasters returned to other duties, except for Denniston; but without a means to decode German naval messages there was little specifically naval work to do.[14]

Capture of the SKM codebook

The first breakthrough for Room 40 came with the capture of the Signalbuch der Kaiserlichen Marine (SKM) from the German light cruiser SMS Magdeburg. Two light cruisers, Magdeburg and SMS Augsburg, and a group of destroyers all commanded by Rear-Admiral Behring were carrying out a reconnaissance of the Gulf of Finland, when the ships became separated in fog. Magdeburg ran aground on the island of Odensholm off the coast of Russian-controlled Estonia. The ship could not be re-floated so the crew was to be taken on board by the destroyer SMS V26. The commander, Korvettenkapitän Habenicht prepared to blow up the ship after it had been evacuated but the fog began to clear and two Russian cruisers Pallada and Bogatyr approached and opened fire. The demolition charges were set off prematurely, causing injuries amongst the crew still on board and before secret papers could be transferred to the destroyer or disposed of. Habenicht and fifty seven of his crew were captured by the Russians.[15]

Exactly what happened to the papers is not clear. The ship carried more than one copy of the SKM codebook and copy number 151 was passed to the British. The German account is that most of the secret papers were thrown overboard, but the British copy was undamaged and was reportedly found in the charthouse. The current key was also needed in order to use the codebook. A gridded chart of the Baltic, the ship's log and war diaries were all also recovered. Copies numbered 145 and 974 of the SKM were retained by the Russians while HMS Theseus was dispatched from Scapa Flow to Alexandrovosk in order to collect the copy offered to the British. Although she arrived on 7 September, due to mix-ups she did not depart until 30 September and returned to Scapa with Captain Kredoff, Commander Smirnoff and the documents on 10 October. The books were formally handed over to the First Lord, Winston Churchill, on 13 October.[16]

The SKM by itself was incomplete as a means of decoding messages, since they were normally enciphered as well as coded and those that could be understood were mostly weather reports. Fleet paymaster C. J. E. Rotter, a German expert from the naval intelligence division, was tasked with using the SKM codebook to interpret intercepted messages, most of which decoded as nonsense since initially it was not appreciated that they were also enciphered. An entry into solving the problem was found from a series of messages transmitted from the German Norddeich transmitter, which were all numbered sequentially and then re-enciphered. The cipher was broken, in fact broken twice as it was changed a few days after it was first solved, and a general procedure for interpreting the messages determined.[17] Enciphering was by a simple table, substituting one letter with another throughout all the messages. Rotter started work in mid October but was kept apart from the other code breakers until November, after he had broken the cipher.[18]

The intercepted messages were found to be intelligence reports on the whereabouts of allied ships. This was interesting but not vital. Russel Clarke now observed that similar coded messages were being transmitted on short-wave, but were not being intercepted because of shortages of receiving equipment, in particular the aerial. Hunstanton was directed to stop listening to the military signals it had been intercepting and instead monitor short-wave for a test period of one weekend. The result was information about the movements of the High Seas Fleet and valuable naval intelligence. Hunstanton was permanently switched to the naval signals and as a result stopped receiving messages valuable to the military. Navy men who had been helping the military were withdrawn to work on the naval messages, without explanation, because the new code was kept entirely secret. The result was a bad feeling between the naval and military interception services and a cessation of cooperation between them, which continued into 1917.[19]

The SKM (sometimes abbreviated SB in German documents) was the code normally used during important actions by the German fleet. It was derived from the ordinary fleet signal books used by both British and German navies, which had thousands of predetermined instructions which could be represented by simple combinations of signal flags or lamp flashes for transmission between ships. The SKM had 34,300 instructions, each represented by a different group of three letters. A number of these reflected old-fashioned naval operations, and did not mention modern inventions such as aircraft. The signals used four symbols not present in ordinary Morse code (given the names alpha, beta, gamma and rho), which caused some confusion until all those involved in interception learnt to recognise them and use a standardised way to write them.[20] Ships were identified by a three-letter group beginning with a beta symbol. Messages not covered by the predetermined list could be spelled out using a substitution table for individual letters.[21]

The sheer size of the book was one reason it could not easily be changed, and the code continued in use until summer 1916. Even then, ships at first refused to use the new codebook because the replacement was too complicated, so the Flottenfunkspruchbuch (FFB) did not fully replace the SKB until May 1917. Doubts about the security of the SKB were initially raised by Behring, who reported that it was not definitely known whether Magdeburg's code books had been destroyed or not, and it was suggested at the court martial enquiry into the loss that books might anyway have been recovered by Russians from the clear shallow waters where the ship had grounded. Prince Heinrich of Prussia, commander in chief of Baltic operations, wrote to the C-in-C of the High Seas Fleet, that in his view it was a certainty that secret charts had fallen into the hands of the Russians, and a probability that the codebook and key had also. The German navy relied upon the re-enciphering process to ensure security, but the key used for this was not changed until 20 October and then not changed again for another three months. The actual substitution table used for enciphering was produced by a mechanical device with slides and compartments for the letters. Orders to change the key were sent out by wireless, and frequently confusion during the changeover period led to messages being sent out using the new cipher and then being repeated with the old. Key changes continued to occur infrequently, only 6 times during 1915 from March to the end of the year, but then more frequently from 1916.[22]

There was no immediate capture of the FFB codebook to help the Admiralty understand it, but instead a careful study was made of new and old messages, particularly from the Baltic, which allowed a new book to be reconstructed. Now that the system was understood, Room 40 reckoned to crack a new key within three to four days, and to have reproduced the majority of a new codebook within two months. A German intelligence report on the matter was prepared in 1934 by Korvettenkapitän Kleikamp which concluded that the loss of Magdeburg's codebook had been disastrous, not least because no steps were taken after the loss to introduce new secure codes.[23]

Capture of the HVB codebook

The second important code used by the German navy was captured at the very start of the war in Australia, although it did not reach the Admiralty until the end of October. The German-Australian steamer Hobart was seized off Port Phillip Heads near Melbourne on 11 August 1914. Hobart had not received news that war had broken out, and Captain J. T. Richardson and party claimed to be a quarantine inspection team. Hobart's crew were allowed to go about the ship but the captain was closely observed, until in the middle of the night he attempted to dispose of hidden papers. The Handelsverkehrsbuch (HVB) codebook which was captured contained the code used by the German navy to communicate with its merchant ships and also within the High Seas Fleet. News of the capture was not passed to London until 9 September. A copy of the book was made and sent by the fastest available steamer, arriving at the end of October.[24]

The HVB was originally issued in 1913 to all warships with wireless, to naval commands and coastal stations. It was also given to the head offices of eighteen German steamship companies to issue to their own ships with wireless. The code used 450,000 possible four-letter groups which allowed alternative representations of the same meaning, plus an alternate ten-letter grouping for use in cables. Re-ciphering was again used but for general purposes was more straightforward, although changed more frequently. The code was used particularly by light forces such as patrol boats, and for routine matters such as leaving and entering harbour. The code was used by U-boats, but with a more complex key. However, the complications of their being at sea for long periods meant that codes changed while they were away and often messages had to be repeated using the old key, giving immediate information about the new one. German intelligence were aware in November 1914 that the HVB code had fallen into enemy hands, as evidenced by wireless messages sent out warning that the code was compromised, but it was not replaced until 1916.[25]

The HVB was replaced in 1916 by the Allgemeinefunkspruchbuch (AFB) together with a new method of keying. The British obtained a good understanding of the new keying from test signals, before it was introduced for real messages. The new code was issued to even more organisations than the previous one, including those in Turkey, Bulgaria and Russia. It had more groups than its predecessor but now of only two letters. The first copy to be captured came from a shot-down Zeppelin but others were recovered from sunk U-boats.[26]

Capture of the VB codebook

A third codebook was recovered following the sinking of German destroyer SMS S119 in the Battle off Texel. In the middle of October 1914, the Battle of the Yser was fought for control of the coastal towns of Dixmude and Dunkirk. The British navy took part by bombarding German positions from the sea and German destroyers were ordered to attack the British ships. On 17 October Captain Cecil Fox commanding the light cruiser Undaunted together with four destroyers, HMS Lance, Lennox, Legion and Loyal, was ordered to intercept an anticipated German attack and met four German destroyers (S115, S117, S118, and S119) heading south from Texel with instructions to lay mines. The German ships were outclassed and all were sunk after a brief battle, whereupon the commander of S119 threw overboard all secret papers in a lead-lined chest. The matter was dismissed by both sides, believing the papers had been destroyed along with the ships. However, on 30 November a British trawler dragged up the chest which was passed to Room 40 (Hall later claimed the vessel had been searching deliberately). It contained a copy of the Verkehrsbuch (VB) codebook, normally used by flag officers of the German Navy. Thereafter the event was referred to by Room 40 as "the miraculous draft of fishes".[27]

The code consisted of 100,000 groups of 5-digit numbers, each with a particular meaning. It had been intended for use in cables sent overseas to warships and naval attachés, embassies and consulates. It was used by senior naval officers with an alternative Lambda key, none of which failed to explain its presence on a small destroyer at the start of the war. Its greatest importance during the war was that it allowed access to communications between naval attachés in Berlin, Madrid, Washington, Buenos Aires, Peking, and Constantinople.[28]

In 1917 naval officers switched to a new code with a new key Nordo for which only 70 messages were intercepted, but the code was also broken. For other purposes VB continued in use throughout the war. Re-ciphering of the code was accomplished using a key made up of a codeword transmitted as part of the message and its date written in German. These were written down in order and then the letters in this key were each numbered according to their order of appearance in the alphabet. This now produced a set of numbered columns in an apparently random order. The coded message would be written out below these boxes starting top left and continuing down the page once a row was filled. The final message was produced by taking the column numbered '1' and reading off its contents downward, then adding on the second column's digits, and so on. In 1918 the key was changed by using the keywords in a different order. This new cipher was broken within a few days by Professor Walter Horace Bruford, who had started working for Room 40 in 1917 and specialised in VB messages. Two messages were received of identical length, one in the new system and one in the old, allowing the changes to be compared.[29]

Room 40

In early November 1914 Captain William Hall, son of the first head of Naval Intelligence, was appointed as the new DID to replace Oliver, who had first been transferred to Naval Secretary to the First Lord and then Chief of the Admiralty War Staff. Hall had formerly been captain of the battlecruiser Queen Mary but had been forced to give up sea duties due to ill health. Hall was to prove an extremely successful DID, despite the accidental nature of his appointment.

Once the new organisation began to develop and show results it became necessary to place it on a more formal basis than squatting in Ewing's office. On 6 November 1914 the organisation moved to Room 40 in the Admiralty Old Building, which was by default to give it its name. Room 40 has since been renumbered, but still exists in the original Admiralty Building off Whitehall, London, on the first floor, with windows looking inwards to a courtyard wholly enclosed by Admiralty buildings. Previous occupants of the room had complained that no one was ever able to find it, but it was on the same corridor as the Admiralty boardroom and the office of the First Sea Lord, Sir John Fisher, who was one of the few people allowed to know of its existence. Adjacent was the First Lord's residence (then Winston Churchill), who was another of those people. Others permitted to know of the existence of a signals interception unit were the Second Sea Lord, the Secretary of the Admiralty, the Chief of Staff (Oliver), the Director of Operations Division (DOD) and the assistant director, the Director of Intelligence Division (DID, Captain William Hall) and three duty captains. Admiral Sir Arthur Wilson, a retired First Sea Lord, had returned to the admiralty to work with the staff and was also included in the secret. The Prime Minister may also have been informed.[30]

All messages received and decoded were to be kept completely secret, with copies only being passed to the Chief of Staff and Director of Intelligence. It was decided that someone from the intelligence department needed to be appointed to review all the messages and interpret them from the perspective of other information. Rotter was initially suggested for the job, but it was felt preferable to retain him in code breaking and Commander Herbert Hope was chosen, who had previously been working on plotting the movements of enemy ships. Hope was initially placed in a small office in the west wing of the Admiralty in the intelligence section, and waited patiently for the few messages which were approved for him to see. Hope reports that he attempted to make sense of what he was given and make useful observations about them, but without access to the wider information being received his early remarks were generally unhelpful. He reported to Hall that he needed more information, but Hall was unable to help. On 16 November, after a chance meeting with Fisher where he explained his difficulties, Hope was granted full access to the information together with instructions to make twice daily reports to the First Sea Lord. Hope knew nothing of cryptanalysis or German, but working with the code breakers and translators he brought detailed knowledge of naval procedures to the process, enabling better translations and then interpretations of received messages. In the interests of secrecy the intention to give a separate copy of messages to the DID was dispensed with so that only the Chief of Staff received one, and he was to show it to the First Sea Lord and Arthur Wilson.[31]

As the number of intercepted messages increased, it became part of Hope's duties to decide which were unimportant and should just be logged, and which should be passed on outside Room 40. The German fleet was in the habit each day of reporting by wireless the position of each ship, and giving regular position reports when at sea. It was possible to build up a precise picture of the normal operation of the High Seas Fleet, indeed to infer from the routes they chose where defensive minefields had been placed and where it was safe for ships to operate. Whenever a change to the normal pattern was seen, it signalled that some operation was about to take place and a warning could be given. Detailed information about submarine movements was available. Most of this information, however, was retained wholly within Room 40 although a few senior members of the Admiralty were kept informed, as a huge priority was placed by the Staff upon keeping secret the British ability to read German transmissions.[32]

Jellicoe, commanding the Grand Fleet, on three occasions requested from the Admiralty that he should have copies of the codebook which his cruiser had brought back to Britain, so that he could make use of it intercepting German signals. Although he was aware that interception was taking place, little of the information ever got back to him, or it did so very slowly. No messages based upon Room 40 information were sent out except those approved by Oliver personally (except for a few authorised by the First Lord or First Sea Lord). Although it might have been impractical and unwise for code breaking to have taken place on board ship, members of Room 40 were of the view that full use was not being made of the information they had collected, because of the extreme secrecy and being forbidden to exchange information with the other intelligence departments or those planning operations.[32]

Signals interception and direction finding

The British and German interception services began to experiment with direction-finding radio equipment in the start of 1915. Captain Round, working for Marconi, had been carrying out experiments for the army in France and Hall instructed him to build a direction-finding system for the navy. At first this was sited at Chelmsford but the location proved a mistake and the equipment was moved to Lowestoft. Other stations were built at Lerwick, Aberdeen, York, Flamborough Head and Birchington and by May 1915 the Admiralty was able to track German submarines crossing the North Sea. Some of these stations also acted as 'Y' stations to collect German messages, but a new section was created within Room 40 to plot the positions of ships from the directional reports. A separate set of five stations was created in Ireland under the command of the Vice Admiral at Queenstown for plotting ships in the seas to the west of Britain and further stations both within Britain and overseas were operated by the Admiral commanding reserves.[33]

The German navy knew of British direction-finding radio and in part this acted as a cover, when information about German ship positions was released for operational use. The two sources of information, from directional fixes and from German reports of their positions, complemented each other. Room 40 was able to observe, using intercepted wireless traffic from Zeppelins which were given position fixes by German directional stations to help their navigation, that the accuracy of British systems was better than their German counterparts. This was explainable by the wider baseline used in British equipment.[34]

Room 40 had very accurate information on the positions of German ships but the Admiralty's priority remained to keep the existence of this knowledge secret. Hope was shown the regular reports created by the Intelligence Division about German ship whereabouts so that he might correct them. This practice was shortly discontinued, for fear of giving away their knowledge. From June 1915, the regular intelligence reports of ship positions were no longer passed to all flag officers, only to Jellicoe, who was the only person to receive accurate charts of German minefields prepared from Room 40 information. Some information was passed to Beatty (commanding the battlecruisers), Tyrwhitt (Harwich destroyers) and Keyes (submarines) but Jellicoe was unhappy with the arrangement. He requested that Beatty should be issued with the Cypher B (reserved for secret messages between the Admiralty and him) to communicate more freely and complained that he was not getting sufficient information.[35]

All British ships were under instructions to use radio as sparingly as possible and to use the lowest practical transmission power. Room 40 had benefited greatly from the free chatter between German ships, which gave them many routine messages to compare and analyse, and from the German habit of transmitting at full power, making the messages easier to receive. Messages to Scapa were never to be sent by wireless, and when the fleet was at sea, messages might be sent using lower power and relay ships (including private vessels), to make German interception more difficult. No attempts were made by the German fleet to restrict its use of wireless until 1917 and then only in response to perceived British use of direction finding, not because it believed messages were being decoded.[35]

Zimmermann Telegram

Room 40 played an important role in several naval engagements during the war, notably in detecting major German sorties into the North Sea that led to the Battle of Dogger Bank in 1915 and the Battle of Jutland in 1916, as the British fleet was sent out to intercept them. Its most notable contribution was in decrypting the Zimmermann Telegram, a telegram from the German Foreign Office sent in January 1917 via Washington to its ambassador Heinrich von Eckardt in Mexico.[36] It has been called the most significant intelligence triumph for Britain during World War I,[36] and one of the earliest occasions on which a piece of signals intelligence influenced world events.[2]

In the telegram's plaintext, Nigel de Grey and William Montgomery learned of German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann's offer to Mexico of United States' territories of Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas as an enticement to join the war as a German ally. The telegram was passed to the U.S. by Captain Hall, and a scheme was devised (involving a still unknown agent in Mexico and a burglary) to conceal how its plaintext had become available and also how the U.S. had gained possession of a copy. The telegram was made public by the United States, which declared war on Germany on 6 April 1917, entering the war on the Allied side.[2]

Staffers

Other staff of Room 40 included Frank Adcock, John Beazley,[37] Francis Birch, Walter Horace Bruford, William 'Nobby' Clarke, Alastair Denniston, Frank Cyril Tiarks and Dilly Knox.

Merger with Military Intelligence (MI)

In 1919, Room 40 was deactivated and its function merged with the British Army's intelligence unit MI1b to form the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS).[38] This unit was housed at Bletchley Park during the Second World War and subsequently renamed Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) and relocated to Cheltenham.

Notes

- Lieutenant Commander James T. Westwood, USN. "Electronic Warfare and Signals Intelligence at the Outset of World War I" (PDF). NSA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2009.

After the war, it was estimated that Room 40 had solved some 15,000 German naval and diplomatic communications, a very great number considering that recoveries were hand-generated.

- "The telegram that brought America into the First World War". BBC History Magazine. 17 January 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- Andrew, Christopher (1996). For The President's Eyes Only. Harper Collins. p. 42. ISBN 0-00-638071-9.

- Massie 2004, pp. 314–317.

- iranica

- Tuchman 1958, pp. 20-21.

- Dooley, John F. (2018). History of Cryptography and Cryptanalysis: Codes, Ciphers, and Their Algorithms. Springer. p. 89. ISBN 978-3-319-90443-6.

- Johnson 1997, pp. 32.

- Massie 2004, p. 580.

- Winkler 2009, pp. 848–849.

- Beesly 1982, pp. 2, 8–9.

- Beesly 1982, pp. 11–12.

- Andrew 1986, p. 87.

- Beesly 1982, pp. 12–14.

- Beesly 1982, pp. 4–5.

- Beesly 1982, pp. 5–6.

- Beesly 1982, pp. 14–15.

- Andrew 1986, p. 90.

- Beesly 1982, p. 15.

- Denniston 2007, p. 32.

- Beesly 1982, pp. 22–23.

- Beesly 1982, pp. 23–26.

- Beesly 1982, p. 25.

- Beesly 1982, pp. 3–4.

- Beesly 1982, p. 26.

- Beesly 1982, pp. 26–27.

- Beesly 1982, pp. 6–7.

- Beesly 1982, pp. 27, 28.

- Beesly 1982, pp. 27–28.

- Beesly 1982, pp. 15–19.

- Beesly 1982, pp. 18–20.

- Beesly 1982, pp. 40–42.

- Beesly 1982, pp. 69–70.

- Beesly 1982, p. 70.

- Beesly 1982, pp. 70–72.

- "Why was the Zimmerman Telegram so important?". BBC. 17 January 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

It was, many believed, the single greatest intelligence triumph for Britain in World War One.

- Martin Robertson; David Gill (2004). "Beazley, Sir John Davidson (1885–1970)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- Erskine & Smith 2011, p. 14

References

- Andrew, Christopher (1986). Her Majesty's Secret Service: The Making of the British Intelligence Community. New York: Viking. ISBN 0-670-80941-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beesly, Patrick (1982). Room 40: British Naval Intelligence, 1914–1918. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 0-241-10864-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Denniston, Robin (2007). Thirty secret years: A.G. Denniston's work for signals intelligence 1914–1944. Polperro Heritage Press. ISBN 0-9553648-0-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Erskine, Ralph; Smith, Michael, eds. (2011). The Bletchley Park Codebreakers. Updated and extended version of Action This Day: From Breaking of the Enigma Code to the Birth of the Modern Computer. Bantam Press, 2001. Biteback. ISBN 978-1-84954-078-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gannon, Paul, (2011). Inside Room 40: The Codebreakers of World War I. Ian Allan Publishing, London, ISBN 978-0-7110-3408-2

- Hoy, Hugh Cleland, (1932) 40 O.B. or How the War Was Won. Hutchison & Co. London, OCLC 10509119.

- Johnson, John (1997). The Evolution of British Sigint, 1653–1939. London: HMSO. OCLC 52130886.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Massie, Robert K. (2004). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0-22404-092-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The Room 40 Compromise, ms., U.S. National Security Agency, 19600101 1960 Doc 3978516

- Tuchman, Barbara (1958). The Zimmermann Telegram. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-32425-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Winkler, Jonathan Reed (July 2009). "Information Warfare in World War I". The Journal of Military History. 73: 845–867. doi:10.1353/jmh.0.0324. ISSN 1543-7795.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- James Wyllie; Michael McKinley (2016). The Codebreakers: The Secret Intelligence Unit That Changed the Course of the First World War. Ebury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-09-195773-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Room 40. |

- The Papers of William Clarke, who worked in Room 40, are held at Churchill Archives Centre in Cambridge and are accessible to the public.

- The Papers of Alexander Denniston, second in command of Room 40, are also held at Churchill Archives Centre.

- The Papers of William Reginald Hall, joint founder of Room 40, are also held at Churchill Archives Centre.

- Original Documents from Room 40: LUSITANIA case; Naval Battle of Jutland/Skagerrak; The Zimmermann/Mexico Telegram; German Submarine Warfare and Room 40 Intelligence in general; PhotoCopies from The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, UK.