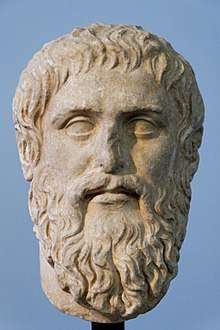

Ninth Letter (Plato)

The Ninth Letter of Plato, also called Epistle IX or Letter IX, is an epistle that is traditionally ascribed to Plato. In the Stephanus pagination, it spans III. 357d–358b.

The letter is ostensibly written to Archytas of Tarentum, whom Plato met during his first trip to Sicily in 387 BC. Archytas had sent a letter with Archippus and Philonides, two Pythagoreans who had gone on to mention to Plato that Archytas was unhappy about not being able to get free of his public responsibilities. The Ninth Letter is sympathetic, noting that nothing is more pleasant than to attend to one's own business, especially when that business is the one that Archytas would engage in (viz. philosophy). Yet everyone has responsibilities to one's fatherland (πατρίς), parents, and friends, to say nothing of the need to provide for daily necessities. When the fatherland calls, it is improper not to answer, especially as a refusal will leave politics to the care of worthless men. The letter then declares that enough has been said of this subject, and concludes by noting that Plato will take care of Echecrates, who is still a youth (νεανίσκος), for Archytas' sake and that of Echecrates' father, as well as for the boy himself.

R. G. Bury describes the Ninth Letter as "a colourless and commonplace effusion which we would not willingly ascribe to Plato, and which no correspondent of his would be likely to preserve;" he also notes "certain peculiarities of diction which point to a later hand."[1] A character by the name of Echecrates also appears in the Phaedo, though Bury suggests that he, if the same person mentioned here, could hardly have been called a youth by the time Plato met Archytas. Despite the fact that Cicero attests to its having been written by Plato,[2] most scholars consider it a literary forgery.

Text

PLATO TO ARCHYTAS OF TARENTUM, WELFARE.

Archippus and Philonides and their companions have come to me with the letter you gave them and have brought me news of you. Their mission to the city they accomplished with no difficulty, since it was not a burdensome matter. But as to you, they reported that you think it a heavy trial not to be able to get free from the cares of public life. It is indeed one of the sweetest things in life to follow one's own interests, especially when they are such as you have chosen; practically everyone would agree. But this also you must bear in mind, that none of us is born for himself alone; a part of our existence belongs to our country, a part to our parents, a part to our other friends, and a large part is given to the circumstances that command our lives. When our country calls us to public service it would, I think, be unnatural to refuse; especially since this means giving place to unworthy men, who enter public life for motives other than the best.

Enough of this. As for Echecrates, I am taking care of him and will do so in the future, both for your sake and the sake of his father Phrynion as well as for the young man himself.

— Ninth Letter, traditionally attributed to Plato[3]

See also

Footnotes

- Bury, Epistle IX, 591.

- Cicero, De Finibus, Bonorum et Malorum, ii. 14; De Officiis, i. 7.

- Cooper, John M.; Hutchinson, D.S. (1997). Plato: Complete Works. Indianapolis: Hackett. p. 1671-1672. ISBN 9780872203495.

References

- Bury, R. G., ed. (1942) Timaeus, Critias, Cleitophon, Menexenus, Epistles. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.