Minos (dialogue)

Minos (/ˈmaɪnɒs, -nəs/; Greek: Μίνως) is purported to be one of the dialogues of Plato. It features Socrates and a companion who together attempt to find a definition of "law" (Greek: νόμος, nómos).

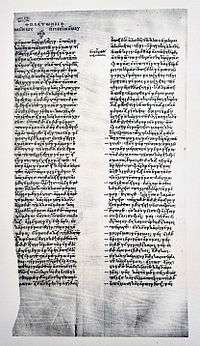

Manuscript: Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, Gr. 1807 (19th century) | |

| Author | Plato or Pseudo-Plato |

|---|---|

| Original title | Μίνως |

| Country | Ancient Greece |

| Language | Greek |

| Subject | Philosophy of law |

| Part of a series on |

| Platonism |

|---|

|

| The dialogues of Plato |

|

| Allegories and metaphors |

| Related articles |

| Related categories |

|

► Plato |

|

Despite its authenticity having been doubted by many scholars,[1] it has often been regarded as a foundational document in the history of legal philosophy,[2] particularly in the theory of natural law.[3] It has also conversely been interpreted as describing a largely procedural theory of law.[4] Ancient commentators have traditionally considered the work as a preamble to Plato's final dialogue, Laws.

Content

The dialogue is normally separated into two sections. In the first half, Socrates and a companion attempt to seek a definition of "law," while in the second half Socrates praises Minos, the mythical king of Crete.[5]

Definition of law

The dialogue opens with Socrates asking his nameless companion, "What is the law for us?" The companion asks from Socrates to clarify which law he means exactly to which Socrates, somewhat surprised, asks from him whether the law is one or many. More specifically, Socrates asks his companion whether different laws are like parts of gold, with each part being from the same essense as the other, or like stones, with each being separate. The companion's answer is that law is nomizomena (νομιζόμενα) or "what is accepted by custom".[6] The Greek word for law is nomos, which is also used to describe an established custom or practice. The companion defines nomos as something nomizomenon (the present passive participle of the related verb nomizō), meaning "accepted." Nomizō is used to mean "practice," "have in common or customary use," "enact," "treat," "consider as" and "belief," amongst other things.[5] Socrates opposes this definition:

Friend: What else would law (nomos) be, Socrates, but what is accepted (nomizomenon)?

Socrates: And so speech, in your view, is what is spoken, or sight what is seen, or hearing what is heard? Or is speech one thing, what is spoken another, sight one thing, what is seen another, hearing one thing, what is heard another—and so law one thing, what is accepted another? Is that so, or what is your view?

Friend: They are two different things, as it now seems to me.

Socrates: Law, then, is not what is accepted.

Friend: I think not.[7]

Just like what we call "hearing" is not the sum of things heard but a sensation, a proper definition of law needs to capture an essense apart from the customary opinions that embody the law at any given moment. Supposing that laws are resolutions of a city,[8] Socrates argues back saying that if we should consider law and justice to always be kaliston (κάλλιστον), "something most noble",[9] while agreeing that a city's resolution can be either "admirable" or "wicked," it follows that identifying the law with these resolutions is incorrect.[10] Instead, Socrates proceeds by asking what is good opinion.

Socrates: But what is a good opinion? Is it not a true opinion?

Friend: Yes.

Socrates: Now isn't true opinion, discovery of reality?

Friend: It is.

Socrates: Then ideally law is discovery of reality.[11]

Socrates goes on to defend his definition of law as "that which wants to discover reality".[12] His companion objects that if that was true then law would be same everywhere, but we know that it isn't, and he gives the example of human sacrifice which is forbidden in Crete where the dialogue takes place, while the Carthaginians and some Greek cities will practice it.[13] Socrates proceeds to counter this argument using his famous method, asking from his companion to give short answers like he did in the Protagoras dialogue. He shows that since law is based on knowing reality, it cannot be different even if it appears to be. Just like the farmer is best at knowing the realities of the land, and the trainer of the human body, so is a king best in knowing the realities of human soul upon which laws should take effect. This is how the dialogue segues into praising Minos, the best, according to Socrates, of kings that have existed.

Praise of Minos

The dialogue eventually proceeds into praise of Minos, the mythical leader of Crete and an ancient enemy of Athens.[14] Socrates counters his companion's opinion that Minos was unjust, saying that his idea is based on theater plays, but once they consult Homer, who is superior to all tragic playwrights put together, they shall find that Minos is worthy of praise. He continues by saying that Minos was the only man to be educated by Zeus himself,[15] and created admirable laws for the Cretans, who are unique in avoiding excessive drinking, later teaching their practice to the Spartans. Minos instructed Rhadamanthus in parts of his "kingly art", enough for him to guard his laws. Zeus then gave Minos a man called Talos, that while though to have been a giant robot made of bronze, Socrates insists that his nickname of "brazen" was due to him holding bronze tablets where Minos' laws were inscribed.[16]

After this encomium, Socrates' companion asks how is it, if everything that he had just heard was true, that Minos has such a bad reputation in Athens.[17] Socrates responds by saying that this was the result of Minos attacking Athens while the city had good poets who, through their art, can harm a person greatly.

Interpretation

Bradley Lewis conceives of the Minos as doing three things: it begins by showing that the ultimate aspiration of law should be truth, while also acknowledging the variety of human laws. This diversity is often taken as an argument against natural law, but the dialogue suggests that the diversity is compatible with the account of the human good being the end of politics. Next, the dialogue underscores the origins of law and legal authority as concrete. Thirdly, the dialogue suggests, but does not explicitly mention, the inherent limitations of contemporary theories of law.[18]

Though the dialogue is often noted as introducing a theory of natural law,[3] the word "nature" (Greek: φύσις phusis) is never used in the dialogue.[19] Mark Lutz argues that Socrates's account of the problematic character of law shows that the concept of natural law is incoherent.[20]

The unnamed interlocutor (Greek: ἑταῖρος hetairos) can be translated in several different ways. Outside of the dialogue, the word is typically translated as "companion," "comrade," "pupil," or "disciple."[21] In the context of Minos however, other conceptions of the interlocutor have been suggested, including being an ordinary citizen,[22][23] a student,[24] a friend,[25] an "Everyman"[26] and the "voice of common sense."[27]

D.S. Hutchinson has pointed out that the combination of "dry academic dialectic together with a literary-historical excursus" is similar to that of other Platonic dialogues, such as the Atlantis myth in Timaeus and Critias, as well other cases in Alcibiades, Second Alcibiades and Hipparchus.[5]

In the dialogue, bodies of laws are conceived as written texts that can be either true of false.[5] In Plato's later dialogue, Laws, he similarly held that legal texts benefit from literary elaboration.[5][28] A proper law is expected to express the reality of social life, which endures just as the ideal city described in Laws would.[5]

The culminating praise of Minos has been interpreted as part of Socrates' intention to liberate the companion from loyalty to Athens and its opinions.

Authenticity

The majority of modern scholars oppose Platonic authorship,[29] including Werner Jaeger,[30] Anton-Hermann Chroust,[31] Jerome Hall,[32] A. E. Taylor[33] and most recently Christopher Rowe.[34] Conversely, there have been cases made arguing in favor of Plato's authorship, including from George Grote,[35] Glenn R. Morrow[36] and William S. Cobb.[37] Paul Shorey suggested that the dialogue may have been partly written by Plato and partly by someone else.[38]

The main arguments against the authenticity of Minos typically say that it is too stylistically crude, philosophically simplistic and too full of poor argumentation to legitimately be Plato.[29] Grote pointed out a flaw in this reasoning, noting that if the dialogue being "confused and unsound"[39] and "illogical"[40] were grounds to exclude it from the Platonic corpus, then one would also have to cast doubt on the Phaedo since Plato's arguments in it for the immortality of the soul are so ineffective.[35][41]

W. R. M. Lamb doubts the authenticity of the dialogue because of its unsatisfying character, though he does consider it a "fairly able and plausible imitation of Plato's early work."[42] Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns do not even include it among Plato's spurious works in their Collected Dialogues.[43] Leo Strauss, on the other hand, considered the dialogue to be authentic enough to write a commentary on it.[44]

The tension between the first half, which extols law as the "discovery of reality," followed by the praising of the mythical figure Minos, who is typically described in tradition as a brutal despot, has been viewed by some as reason to doubt the dialogue.[45] This apparent incoherence between the two parts of the dialogue has been utilized as one argument against Platonic authorship,[38] though others have seen the introduction of Minos as being perfectly coherent.[46]

Placement in the Platonic Corpus

Many historical commentators have viewed the Minos as a kind of introduction to the Laws.[18] Aristophanes of Byzantium placed the Minos with the Laws in his organization of Plato's writings as trilogies and tetralogies,[47][lower-alpha 1] as did Thrasyllus in his later tetralogical organization of the Platonic corpus:[48][lower-alpha 2]

| Placement | Aristophanes's trilogy organization[47] | Aristophanes's tetralogy organization[47] | Thrasyllus's tetralogy organization[47] |

| 1 | Laws | Minos | Minos |

| 2 | Minos | Laws | Laws |

| 3 | Epinomis | Epinomis | Epinomis |

| 4 | – | Letters | Letters |

Because of the similarities in style to the Hipparchus, many scholars have concluded that they are the work of the same author, written soon after the middle of the fourth century B.C.[25] Böckh ascribed the dialogue to a minor Socratic, Simon the Shoemaker,[29][49] who is mentioned by Diogenes Laërtius as a note-taker of Socrates.[50]

References

Footnotes

- Aristophanes placed Minos in the third of five collections for the trilogy organization, and in the ninth and final collection for the tetralogy organization.[47]

- Thrasyllus placed Minos in the ninth and final collection in his tetralogy organization.[48]

Citations

-

- Boeckh 1806

- Heidel 1896, pp. 39–43

- Lewis 2006, p. 17

- Pavlu 1910

- Schleiermacher 1996, pp. 171–173

-

- Cairns 1949, pp. 31–32

- Cairns 1970

- Chroust 1947

- Jaeger 1947, pp. 369–370

- Lewis 2006, p. 17

-

- Annas 1995, p. 303 n. 47

- Cairns 1949, pp. 33–37

- Chroust 1947, pp. 48–49

- Crowe 1977, p. xi

- Fassò 1966, pp. 78–79

- George 1993, pp. 149–150

- Grote 1888, pp. 421–425

- Hathaway & Houlgate 1969

- Jaeger 1947, pp. 370–371

- Lewis 2006, p. 18

- Maguire 1947, p. 153

- Shorey 1933, p. 425

- Best 1980, pp. 102–113.

- Hutchinson 1997, p. 1307.

- Plato, Minos, 313a–b

- Plato, Minos, 313b–c

- Plato, Minos, 314c

- Plato, Minos, 314d

- Plato, Minos, 314e

- Plato, Minos, 314e–315a

- Plato, Minos, 315a–318d

- Plato, Minos, 315c

- Plato, Minos, 318d–321b

- Plato, Minos, 319d–e

- Plato, Minos, 320c

- Plato, Minos, 320e

- Lewis 2006, p. 20.

- Lewis 2006, p. 18

- Lutz 2010.

- Lidell & Scott 1940.

- Grote 1888, p. 71.

- Jaeger 1947, p. 370.

- Chroust 1947, p. 49.

- Hutchinson 1997, pp. 1307–1308.

- Hathaway & Houlgate 1969, p. 107.

- Best 1980, pp. 103, 107.

- Plato, Laws, 718c-723d

- Lewis 2006, p. 17.

- Jaeger 1947, pp. 369–370, 375 n. 74.

- Chroust 1947, pp. 52–53.

- Hall 1956, p. 199.

- Taylor 1952, p. 540.

- Rowe 2000, pp. 303–309.

- Grote 1888, p. 93–97.

- Morrow 1960, pp. 35–39.

- Cobb 1988, pp. 187–207.

- Shorey 1933, p. 425.

- Grote 1888, p. 88.

- Grote 1888, p. 95.

- Lewis 2006, p. 18.

- Lamb 1927, p. 386.

- Hamilton & Cairns 1961.

- Strauss 1968.

- Lewis 2006, p. 19.

-

- Best 1980, p. 102

- Chroust 1947, pp. 52–53

- Jaeger 1947, pp. 370–371

- Strauss 1968

- Schironi 2005.

- Tarrant 1993.

- Boeckh 1806.

- Diogenes Laërtius, Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, 2.122-3

Sources

- Annas, Julia (1995). The Morality of Happiness. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1950-9652-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Best, Judith (1980). "What is Law? The Minos Reconsidered". Interpretation. 8: 102–113.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Boeckh, August (1806). In Platonis qui vulgo fertur Minoem. Halle: Hemmerde.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cairns, Huntington (1949). Legal Philosophy From Plato to Hegel. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-3132-1499-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cairns, Huntington (1970). "What is Law?". Washington and Lee Law Review. 27 (199).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chroust, Anton-Hermann (1947). "An Anonymous Treatise on Law: The Pseudo-Platonic Minos". Notre Dame Lawyer. 23 (48).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cobb, William S. (1988). "Plato's Minos". Ancient Philosophy. 8 (2): 187–207. doi:10.5840/ancientphil1988823.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Crowe, Michael Bertram (1977). The Changing Profile of the Natural Law. BRILL. ISBN 978-9-0247-1992-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fassò, Guido (1966). Storia della filosofia de diritto. 1. Bologna: Società editrice il Mulino.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- George, Robert P. (1993). "Natural Law and Civil Rights: From Jefferson's 'Letter to Henry Lee' to Martin Luther King's 'Letter from Birmingham Jail'". Catholic University Law Review. 43 (143): 143–157.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grote, George (1888). Plato and the Other Companions of Sokrates. 1 (3d ed.). London: John Murray. pp. 421–425.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hamilton, Edith; Cairns, Hungtington, eds. (1961). The Collected Dialogues of Plato. Princeton: Princeton University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hathaway, R. F.; Houlgate, L. D. (1969). "The Platonic Minos and the Classical Theory of Natural Law". American Journal of Jurisprudence. 14 (1): 105–115. doi:10.1093/ajj/14.1.105.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heidel, W. A. (1896). Pseudo-Platonica. Baltimore: Friedenwald. ISBN 978-1-2963-8838-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hutchinson, D. S. (1997). "Introduction to the Minos". Complete Works/Plato. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company. pp. 1307–1308. ISBN 978-0-8722-0349-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jaeger, Werner (1947). "Praise of Law: The Origin of Legal Philosophy and the Greeks". In Sayer, Paul (ed.). Interpretations of Modern Legal Philosophy: Essays in Honor of Roscoe Pound. Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hall, Jerome (1956). "Plato's Legal Philosophy". Indiana Law Journal. 31.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lamb, W. R. M. (1927). "Introduction to the Minos". Charmides, Alcibiades, Hipparchus, The Lovers, Theages, Minos, Epinomis. Cambridge: Loeb Classical Library.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lewis, V. Bardley (September 2006). "Plato's "Minos:" the Political and Philosophical Context of the Problem of Natural Right". The Review of Metaphysics. 60 (1): 17–53. JSTOR 20130738.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lidell, Henry; Scott, Robert (1940). A Greek–English Lexicon (9th ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lutz, Mark (2010). "The Minos and the Socratic Examination of Law". American Journal of Political Science. 54 (4): 988–1002. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00466.x.

- Maguire, Joseph P. (1947). Plato's Theory of Natural Law. Yale University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morrow, Glenn R. (1960). Plato's Cretan City: A Historical Interpretation of the "Laws". Princeton: Princeton University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pavlu, Josef (1910). Die pseudoplatonischen Zwillingsdialoge Mino und Hippareh (in German). Vienna: Verlag de K. K. Staatsgymnasiums.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rowe, Christopher (2000). "Cleitophon and Minos". In Rowe, Christopher; Schofield, Malcolm (eds.). Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Political Thought. Cambridge University Press. pp. 303–309.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schironi, Francesca (2005). "Plato at Alexandria: Aristophanes: Aristarchus, and the 'Philological Tradition' of a Philosopher". The Classical Quarterly. 55 (2): 423–434. doi:10.1093/cq/bmi040. ISSN 1471-6844.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schleiermacher, Friedrich (1996). "Introduction to the 'Minos'". In Steiner, Peter (ed.). Uber die Philosophie Platons. Felix Meiner Verlag. pp. 171–173.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shorey, Paul (1933). What Plato Said. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Strauss, Leo (1968). "On the Minos". Liberalism Ancient and Modern. Cornell University Press. pp. 65–75.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tarrant, H. (1993). Thrasyllan Platonism. Ithaca.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taylor, A. E. (1952). Plato: The Man and His Work. New York: Humanities Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Minos translated by George Burges

- Free public domain audiobook version of Minos translated by George Burges

- Laws. Rare Henry Cary literal translation from the Bohn's Classical Library (Harvard, 1859)

- Laws at Project Gutenberg, a 19th-century nonliteral translation by Jowett.

- Laws from the Perseus Digital Library; transl. R. G. Bury (1967–1968). Greek and English text parallel.