The School of Athens

The School of Athens (Italian: Scuola di Atene) is a fresco by the Italian Renaissance artist Raphael. It was painted between 1509 and 1511 as a part of Raphael's commission to decorate the rooms now known as the Stanze di Raffaello, in the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican. The Stanza della Segnatura was the first of the rooms to be decorated, and The School of Athens, representing philosophy, was probably the third painting to be finished there, after La Disputa (Theology) on the opposite wall, and the Parnassus (Literature).[1] The painting is notable for its accurate perspective projection,[2] which Raphael learned from Leonardo da Vinci (who is the central figure of this painting, representing Plato). The rebirth of Ancient Greek Philosophy and culture in Europe (along with Raphael‘s work) were inspired by Leonardo’s individual pursuits in theatre, engineering, optics, geometry, physiology, anatomy, history, architecture and art. This work has long been seen as "Raphael's masterpiece and the perfect embodiment of the classical spirit of the Renaissance".[3]

| The School of Athens | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Raphael |

| Year | 1509–1511 |

| Type | Fresco |

| Dimensions | 500 cm × 770 cm (200 in × 300 in) |

| Location | Apostolic Palace, Vatican City |

Program, subject, figure identifications and interpretations

The School of Athens is one of a group of four main frescoes on the walls of the Stanza (those on either side centrally interrupted by windows) that depict distinct branches of knowledge. Each theme is identified above by a separate tondo containing a majestic female figure seated in the clouds, with putti bearing the phrases: "Seek Knowledge of Causes," "Divine Inspiration," "Knowledge of Things Divine" (Disputa), "To Each What Is Due." Accordingly, the figures on the walls below exemplify Philosophy, Poetry (including Music), Theology, and Law.[4] The traditional title is not Raphael's. The subject of the "School" is actually "Philosophy," or at least ancient Greek philosophy, and its overhead tondo-label, "Causarum Cognitio", tells us what kind, as it appears to echo Aristotle's emphasis on wisdom as knowing why, hence knowing the causes, in Metaphysics Book I and Physics Book II. Indeed, Plato and Aristotle appear to be the central figures in the scene. However, all the philosophers depicted sought knowledge of first causes. Many lived before Plato and Aristotle, and hardly a third were Athenians. The architecture contains Roman elements, but the general semi-circular setting having Plato and Aristotle at its centre might be alluding to Pythagoras' circumpunct.

Commentators have suggested that nearly every great ancient Greek philosopher can be found in the painting, but determining which are depicted is difficult, since Raphael made no designations outside possible likenesses, and no contemporary documents explain the painting. Compounding the problem, Raphael had to invent a system of iconography to allude to various figures for whom there were no traditional visual types. For example, while the Socrates figure is immediately recognizable from Classical busts, the alleged Epicurus is far removed from his standard type. Aside from the identities of the figures depicted, many aspects of the fresco have been variously interpreted, but few such interpretations are unanimously accepted among scholars.

The popular idea that the rhetorical gestures of Plato and Aristotle are kinds of pointing (to the heavens, and down to earth) is very likely. However, Plato's Timaeus – which is the book Raphael places in his hand – was a sophisticated treatment of space, time, and change, including the Earth, which guided mathematical sciences for over a millennium. Aristotle, with his four-elements theory, held that all change on Earth was owing to motions of the heavens. In the painting Aristotle carries his Ethics, which he denied could be reduced to a mathematical science. It is not certain how much the young Raphael knew of ancient philosophy, what guidance he might have had from people such as Bramante and whether a detailed program was dictated by his sponsor, Pope Julius II.

Nevertheless, the fresco has even recently been interpreted as an exhortation to philosophy and, in a deeper way, as a visual representation of the role of Love in elevating people toward upper knowledge, largely in consonance with contemporary theories of Marsilio Ficino and other neo-Platonic thinkers linked to Raphael.[5]

Finally, according to Giorgio Vasari, the scene includes Raphael himself, the Duke of Mantua, Zoroaster and some Evangelists.[6]

However, to Heinrich Wölfflin, "it is quite wrong to attempt interpretations of the School of Athens as an esoteric treatise ... The all-important thing was the artistic motive which expressed a physical or spiritual state, and the name of the person was a matter of indifference" in Raphael's time.[7] Raphael's artistry then orchestrates a beautiful space, continuous with that of viewers in the Stanza, in which a great variety of human figures, each one expressing "mental states by physical actions," interact, in a "polyphony" unlike anything in earlier art, in the ongoing dialogue of Philosophy.[8]

An interpretation of the fresco relating to hidden symmetries of the figures and the star constructed by Bramante was given by Guerino Mazzola and collaborators.[9] The main basis are two mirrored triangles on the drawing from Bramante (Euclid), which correspond to the feet positions of certain figures.[10]

Figures

The identities of some of the philosophers in the picture, such as Plato and Aristotle, are certain. Beyond that, identifications of Raphael's figures have always been hypothetical. To complicate matters, beginning from Vasari's efforts, some have received multiple identifications, not only as ancients but also as figures contemporary with Raphael. Vasari mentions portraits of the young Federico II Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua, leaning over Bramante with his hands raised near the bottom right, and Raphael himself.[11]

Central figures (14 and 15)

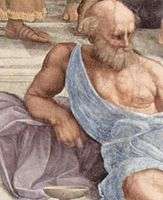

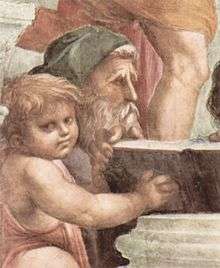

In the center of the fresco, at its architecture's central vanishing point, are the two undisputed main subjects: Plato on the left and Aristotle, his student, on the right. Both figures hold modern (of the time), bound copies of their books in their left hands, while gesturing with their right. Plato holds Timaeus and Aristotle holds his Nicomachean Ethics. Plato is depicted as old, grey, and bare-foot. By contrast, Aristotle, slightly ahead of him, is in mature manhood, wearing sandals and gold-trimmed robes, and the youth about them seem to look his way. In addition, these two central figures gesture along different dimensions: Plato vertically, upward along the picture-plane, into the vault above; Aristotle on the horizontal plane at right-angles to the picture-plane (hence in strong foreshortening), initiating a flow of space toward viewers.

It is popularly thought that their gestures indicate central aspects of their philosophies, for Plato, his Theory of Forms, and for Aristotle, an emphasis on concrete particulars. Many interpret the painting to show a divergence of the two philosophical schools. Plato argues a sense of timelessness whilst Aristotle looks into the physicality of life and the present realm.

Setting

The building is in the shape of a Greek cross, which some have suggested was intended to show a harmony between pagan philosophy and Christian theology[3] (see Christianity and Paganism and Christian philosophy). The architecture of the building was inspired by the work of Bramante, who, according to Vasari, helped Raphael with the architecture in the picture.[3] The resulting architecture was similar to the then new St. Peter's Basilica.[3]

There are two sculptures in the background. The one on the left is the god Apollo, god of light, archery and music, holding a lyre.[3] The sculpture on the right is Athena, goddess of wisdom, in her Roman guise as Minerva.[3]

The main arch, above the characters, shows a meander (also known as a Greek fret or Greek key design), a design using continuous lines that repeat in a "series of rectangular bends" which originated on pottery of the Greek Geometric period and then become widely used in ancient Greek architectural friezes.[12]

Drawings and cartoon

A number of drawings made by Raphael as studies for the School of Athens are extant.[13] A study for the Diogenes is in the Städel in Frankfurt[14] while a study for the group around Pythagoras, in the lower left of the painting, is preserved in the Albertina Museum in Vienna.[15] Several drawings, showing the two men talking while walking up the steps on the right and the Medusa on Athena's shield,[16][lower-alpha 1] the statue of Athena (Minerva) and three other statues,[18] a study for the combat scene in the relief below Apollo[19] and "Euclid" teaching his pupils[20] are in the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology at the University of Oxford.

The cartoon for the painting is in the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan.[21] Missing from it is the architectural background, the figures of Heraclitus, Raphael, and Protogenes. The group of the philosophers in the left foreground strongly recall figures from Leonardo's Adoration of the Magi.[22] Additionally, there are some engravings of the scene's sculptures by Marcantonio Raimondi; they may have been based on lost drawings by Raphael, as they do not match the fresco exactly.[23]

Copies

The Victoria and Albert Museum in London has a rectangular version over 4 metres by 8 metres in size, painted on canvas, dated 1755 by Anton Raphael Mengs on display in the eastern Cast Court.[24]

Modern reproductions of the fresco abound. For example, a full-size one can be seen in the auditorium of Old Cabell Hall at the University of Virginia. Produced in 1902 by George W. Breck to replace an older reproduction that was destroyed in a fire in 1895, it is four inches off scale from the original, because the Vatican would not allow identical reproductions of its art works.[25]

Other reproductions include: in Königsberg Cathedral, Kaliningrad by Neide,[26] in the University of North Carolina at Asheville's Highsmith University Student Union, and a recent one in the seminar room at Baylor University's Brooks College. A copy of Raphael's School of Athens was painted on the wall of the ceremonial stairwell that leads to the famous, main-floor reading room of the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève in Paris.

The two figures to the left of Plotinus were used as part of the cover art of both Use Your Illusion I and II albums of Guns N' Roses.

Subject

A similar subject is known as Plato's Academy mosaic, and perhaps emerged in form of statues at the Serapeum of Alexandria and Memphis Saqqara, both of them in what is now Egypt. Jean-François Mimaut (1774 - 1837), French consul-general in Alexandria, mentioned in the 19th century nine statues at Serapeum of Alexandria holding rolls. Eleven statues were found at Saqqara. A review of "Les Statues Ptolémaïques du Sarapieion de Memphis" noted they were probably sculpted in the 3rd century with limestone and stucco, some standing and others sitting. Rowe and Rees 1956 suggested that both scenes in the Serapeum of Alexandria and Saqqara share a similar subject, such as with Plato's Academy mosaic, with Saqqara figures attributed to: "(1) Pindare, (2) Démétrios de Phalère, (3) x (?), (4) Orphée (?) aux oiseaux,[27] (5) Hésiode, (6) Homère, (7) x (?), (8) Protagoras, (9) Thalès, (10) Héraclite, (11) Platon, (12) Aristote (?)."[28][29] However, there have been other suggestions (see for instance Mattusch, 2008). A common identification seems to be Plato as a central figure and Thales.[30] According to Paolo Zamboni professor of Vascular Surgery University of Ferrara who carried out an Iconodiagnostic on the School of Athens, Raphael's Michelangelo, in the role of Heraclitus, is affected by legs and knees varicose veins.[31]

Gallery

Pythagoras and Archimedes

Pythagoras and Archimedes Archimedes displaying his Principle.

Archimedes displaying his Principle.

Diogenes

Diogenes

Averroes and Pythagoras

Averroes and Pythagoras

Notes

Footnotes

- Possibly derived from a figure in Leonardo's Battle of Anghiari.[17]

Citations

- Jones and Penny, p. 74: "The execution of the School of Athens ... probably followed that of the Parnassus."

- Georg Rainer Hofmann (1990). "Who invented ray tracing?". The Visual Computer. 6 (3): 120–124. doi:10.1007/BF01911003..

- History of Art: The Western Tradition by Horst Woldemar Janson, Anthony F. Janson (2004).

- See Giorgio Vasari, "Raphael of Urbino", in Lives of the Artists, vol. I: "In each of the four circles he made an allegorical figure to point the significance of the scene beneath, towards which it turns. For the first, where he had painted Philosophy, Astrology, Geometry and Poetry agreeing with Theology, is a woman representing Knowledge, seated in a chair supported on either side by a goddess Cybele, with the numerous breasts ascribed by the ancients to Diana Polymastes. Her garment is of four colours, representing the four elements, her head being the colour of fire, her bust that of air, her thighs that of earth, and her legs that of water." For further clarification, and introduction to more subtle interpretations, see E. H. Gombrich, "Raphael’s Stanza della Segnatura and the Nature of Its Symbolism", in Symbolic Images: Studies in the Art of the Renaissance (London: Phaidon, 1975).

- M. Smolizza, ‘’Rafael y el Amor. La Escuela de Atenas como protréptico a la filosofia’’, in ‘Idea y Sentimiento. Itinerarios por el dibujo de Rafael a Cézanne’, Barcelona, 2007, pp. 29–77. [A review of the main interpretations proposed in the last two centuries.]

- According to Vasari, "Raphael received a hearty welcome from Pope Julius, and in the chamber of the Segnatura he painted the theologians reconciling Philosophy and Astrology with Theology, including portraits of all the wise men of the world in dispute."

- Wōlfflin, p. 88.

- Wōlfflin, pp. 94ff.

- Guerino Mazzola; et al. (1986). Rasterbild - Bildraster. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-17267-3.

- This can be seen here.

- Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists, v. I, sel. & transl. by George Bull (London: Penguin, 1965), p. 292.

- Lyttleton, Margaret. "Meander." Grove Art Online. Oxford University Press, 2012. Accessed 5 August 2012.

- Luitpold Dussler: Raphael. A Critical Catalogue (London and New York: Phaidon 1971), p. 74

- Zeichnungen – 16. Jahrhundert – Graphische Sammlung – Sammlung – Städel Museum. Staedelmuseum.de (2010-11-18). Retrieved on 2011-06-13.

- Raffaello Santi. mit seinen Schülern (Studie für die "Schule von Athen", Stanza della Segnatura, Vatikan) (trans.: Pythagoras and his students (Study for the 'School of Athens', Stanza della Signatura, the Vatican) (inventory number 4883)). Albertina Museum. Vienna, Austria, 2008. Retrieved on 2011-06-13.

- "Two Men conversing on a Flight of Steps, and a Head shouting". Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology. University of Oxford. 2011. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- Salmi, Mario; Becherucci, Luisa; Marabottini, Alessandro; Tempesti, Anna Forlani; Marchini, Giuseppe; Becatti, Giovanni; Castagnoli, Ferdinando; Golzio, Vincenzo (1969). The Complete Work of Raphael. New York: Reynal and Co., William Morrow and Company. p. 378.

- "Studies for a Figure of Minerva and Other Statues". Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology. University of Oxford. 2011. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- "Recto: Combat of nude men". Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology. University of Oxford. 2011. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- Raphael (1482-1520).Euclid instructing his Pupils. Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Oxford, 2011. Retrieved on 2011-06-13.

- School of Athens Cartoon

- Salmi, Mario; Becherucci, Luisa; Marabottini, Alessandro; Tempesti, Anna Forlani; Marchini, Giuseppe; Becatti, Giovanni; Castagnoli, Ferdinando; Golzio, Vincenzo (1969). The Complete Work of Raphael. New York: Reynal and Co., William Morrow and Company. p. 379.

- Salmi, Mario; Becherucci, Luisa; Marabottini, Alessandro; Tempesti, Anna Forlani; Marchini, Giuseppe; Becatti, Giovanni; Castagnoli, Ferdinando; Golzio, Vincenzo (1969). The Complete Work of Raphael. New York: Reynal and Co., William Morrow and Company. pp. 377, 422.

- V&A Museum: Copy of Raphael's School of Athens in the Vatican. collections.vam.ac.uk (2009-08-25). Retrieved on 2016-03-24.

- Information on Old Cabell Hall from University of Virginia

- Northern Germany: As Far as the Bavarian and Austrian Frontiers, Baedeker, 1890, p. 247.

- French for to birds.

- Alan Rowe; B. R. Rees (1956). "A Contribution To The Archaeology of The Western Desert: IV - The Great Serapeum Of Alexandria" (PDF). Manchester.

- Ph. Lauer; Ch. Picard (1957). "Reviewed Work: Les Statues Ptolémaïques du Sarapieion de Memphis". Archaeological Institute of America. 61 (2): 211–215. doi:10.2307/500375. JSTOR 500375.

- Katherine Joplin (2011). "Plato's Circle in the Mosaic of Pompeii". Electrum Magazine.

- "Diagnosi su tela: le grandi malattie dipinte dei pittori del passato".

References

- Roger Jones and Nicholas Penny, Raphael, Yale, 1983, ISBN 0300030614.

- Heinrich Wölfflin, Classic Art: An Introduction to the Italian Renaissance (London: Phaidon, 2d edn. 1953).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The School of Athens. |

- The School of Athens on In Our Time at the BBC

- The School of Athens at the Web Gallery of Art

- The School of Athens (interactive map)

- Cartoon of The School of Athens

- The School of Athens reproduction at UNC Asheville

- BBC Radio 4 discussion about the significance of this picture in the programme In Our Time with Melvyn Bragg.

- 3 Cool Things You Might Not Know About Raphael’s School of Athens