Social emotional development

Social emotional development represents a specific domain of child development. It is a gradual, integrative process through which children acquire the capacity to understand, experience, express, and manage emotions and to develop meaningful relationships with others.[1] As such, social emotional development encompasses a large range of skills and constructs, including, but not limited to: self-awareness, joint attention, play, theory of mind (or understanding others' perspectives), self-esteem, emotion regulation, friendships, and identity development.

Social emotional development sets a foundation for children to engage in other developmental tasks. For example, in order to complete a difficult school assignment, a child may need the ability to manage their sense of frustration and seek out help from a peer. To maintain a romantic relationship after a fight, a teen may need to be able to articulate their feelings and take the perspective of their partner to successfully resolve the conflict. However, it is also interrelated with and dependent on other developmental domains. For example, language delays or deficits have been associated with social-emotional disturbances.[2]

Many mental health disorders, including major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, borderline personality disorder, substance use disorders, and eating disorders, can be conceptualized through the lens of social emotional development, most prominently emotion regulation.[3] Many of the core symptoms of autism spectrum disorder reflect abnormalities in social emotional developmental areas, including joint attention[4] and theory of mind.[5]

Early childhood (birth to 3 years old)

Attachment

Attachment refers to the strong bond that individuals develop with special people in their lives. Though we can have attachment relationships with significant others in adulthood, such as marital partners, most humans’ first and most influential attachment is with their primary caregiver(s) as infants. John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth first delineated and tested attachment theory as an evolutionarily informed process in which the emotional ties to a caregiver are adaptive for survival.[6] Their research supported the presence of four stages of attachment formation:[7][8]

- Undiscriminating social responsiveness (0–3 months) – Instinctual infant signals, such as crying, gazing, gasping, help facilitate caregiver interactions with infants. Infants do not consistently discriminate with whom they signal or how they respond.

- Preferential social responsiveness (3–6 months) – Infants now clearly respond differently to primary caregiver(s) than strangers. Infants have learned that this caregiver will consistently respond to their signals.

- Emergence of secure-base behavior (6–24 months) – Young children use their attachment figure as a “secure base” from which to explore the world and a “safe haven” to return to for reassurance or comfort. When the attachment figure is not available, children may exhibit separation anxiety.

- Partnership (24 months and older) – Children develop an internal working model about the availability and responsiveness of attachment figures that can impact their future behavior and relationships.

Early attachment is considered foundational to later social-emotional development, and is predictive of many outcomes, including internalizing problems, externalizing problems, social competence, self-esteem, cognitive development, and achievement.[7] Mary Ainsworth's work using the Strange Situation method identified four types of attachment styles in young children:

- Secure attachment: Children in this category are willing to explore the room/toys independently when their caregiver is present. They may cry when separated, but seek out comfort and are easily soothed when their caregiver returns. This style is associated with sensitive, responsive care by the attachment figure.

- Anxious/Avoidant attachment: Children in this category tend to be less responsive to separation from their caregiver, do not differentiate as clearly between caregivers and strangers, and are avoidant of caregivers upon return. This style is associated with overstimulating care or by consistently detached care.

- Anxious/Ambivalent attachment: Children in this category may seek out closeness with caregiver and appear unwilling to explore. They show distress upon separation and may appear both mad (e.g., hitting, struggling) and clingy when the caregiver returns. These children are often harder to soothe. This style is associated with inconsistent responsiveness or maternal interference with exploration.

- Disorganized attachment: Children in this category often do not show a predictable pattern of behavior, but may be non-responsive or demonstrate flat affect. This style is associated with unpredictable and/or frightening experiences with caregivers, and is more common in children who have experienced maltreatment.

Emotional experiences

Emotional expression

Beginning at birth, newborns have the capacity to signal generalized distress in response to unpleasant stimuli and bodily states, such as pain, hunger, body temperature, and stimulation.[7] They may smile, seemingly involuntarily, when satiated, in their sleep, or in response to pleasant touch. Infants begin using a “social smile,” or a smile in response to a positive social interaction, at approximately 2 to 3 months of age, and laughter begins at 3 to 4 months.[7] Expressions of happiness become more intentional with age, with young children interrupting their actions to smile or express happiness to nearby adults at 8–10 months of age, and with markedly different kinds of smiles (e.g., grin, muted smile, mouth open smile) developing at 10 to 12 months of age.[7]

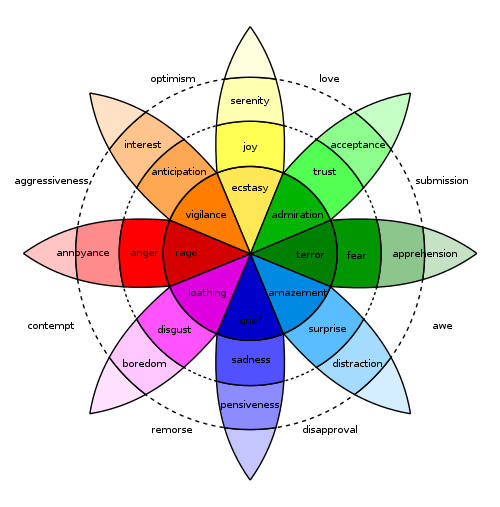

Between 18–24 months, children begin to acquire a sense of self. This gives rise to the onset of self-conscious emotions (e.g., shame, embarrassment, guilt, pride) around that same age, which are considered more complex in nature than basic emotions such as happiness, anger, fear, or disgust. This is because they require that children have recognition of external standards, and evaluative capacities to determine whether the self meets that standard.[9]

Emotion regulation

Emotion regulation can be defined by two components. The first, “emotions as regulating,” refers to changes that are elicited by activated emotions (e.g., a child's sadness eliciting a change in parent response).[10] The second component is labeled “emotions as regulated,” which refers to the process through which the activated emotion is itself changed by deliberate actions taken by the self (e.g., self-soothing, distraction) or others (e.g., comfort).[10]

Throughout infancy, children rely heavily on their caregivers for emotion regulation; this reliance is labeled co-regulation. Caregivers use strategies such as distraction and sensory input (e.g., rocking, stroking) to regulate infants’ emotions. Despite reliance on caregivers to change the intensity, duration, and frequency of emotions, infants are capable of engaging in self-regulation strategies as young as 4 months. At this age, infants intentionally avert their gaze from overstimulating stimuli.[7] By 12 months, infants use their mobility in walking and crawling to intentionally approach or withdraw from stimuli.[7]

Throughout toddlerhood, caregivers remain important for the emotional development and socialization of their children, through behaviors such as: labeling their child's emotions, prompting thought about emotion (e.g., “why is the turtle sad?”), continuing to provide alternative activities/distractions, suggesting coping strategies, and modeling coping strategies.[7] Caregivers who use such strategies and respond sensitively to children's emotions tend to have children who are more effective at emotion regulation, are less fearful and fussy, more likely to express positive emotions, easier to soothe, more engaged in environmental exploration, and have enhanced social skills in the toddler and preschool years.[7]

Understanding others

Social referencing

.png)

Starting at about 8–10 months, infants begin to engage in social referencing, in which they refer to another, often an adult or caregiver, to inform their reaction to environmental stimuli.[7] In the classic visual cliff experiments, 12-month-old babies who were separated from their mothers by a plexiglass floor that appeared to represent a dangerous “cliff” looked to their mothers for a cue.[11] When mothers responded to their infants with facial expressions signaling encouragement and happiness, most infants crossed over the cliff. In contrast, if mothers displayed fear or anger, most infants did not cross.

As infants age, their social referencing capacity becomes more developed. By 14 months, infants are able to use information gained from social referencing to inform decisions outside of the immediate moment.[7] By 18 months, infants are able to socially reference interactions not directed at them.[7] For example, if their caregiver responded with anger when their older brother went to take a cookie, the infant is able to harness that information and is less likely to take a cookie themselves. At this age, social referencing also begins to support children's understanding of others, as children learn what others like and dislike based on the information gained from social referencing (e.g., facial expression). As such, if an adult reacts by smiling when given a ball but with anger when given a doll, an 18-month-old will choose to give that adult a ball, rather than a doll, regardless of their own preferences.

Empathy

From an early age, newborns are reactive to others’ distress, as evidenced by behaviors such as crying in response to another infant's cry. As children continue to develop, they begin to display behaviors that indicate an understanding of and connection to others’ emotional states beyond the simple informational value those emotional states provide. Children at 18–30 months will respond to verbal and nonverbal cues, such as facial expressions or body posture, of discomfort or sadness with simple helping behaviors (e.g., giving an adult a blanket if they are shivering, rubbing their arms, and saying “brr”).[12] Throughout this period (18–30 months), children become more adept and need fewer cues to engage in helping behavior. However, helping behavior at this age is already dependent on the cost of helping (e.g., they are less likely to give the adult their own blanket) and the recipient of the help (e.g., children are more likely to help and show concern for caregivers than strangers or peers).[12]

Social interactions

Between 3 and 6 months old, infants begin engaging in simple back-and-forth exchanges, often with their caregivers.[7] These exchanges do not consist of words, but of coos, gurgles, smiles or other facial expressions, and bodily movements (e.g., lifting arms, kicking legs).[13] These back and forth exchanges mimic the turn-taking that occurs in conversations.

Joint attention

Joint attention refers to the ability of individuals to share a common point of reference or attention.[14] In children, this common point of reference often is an object in the environment, such as a toy. The development of joint attention initially starts with the infants' ability to respond to joint attention bids (e.g., looking where their parent looks), and eventually develops with age to the ability to initiate joint attention by directing the attention of another to shared point of reference.[14] This can be done through many means, including gaze, gesture (e.g., pointing, showing), or speech.

As early as 3 to 4 months of age, infants show the beginning requisites of joint attention, by looking in the general direction as adults; however, they are not consistently able to find the shared point of reference.[7] At 10 months, this accuracy improves,[7] and infants are also more discerning in their response to joint attention. For example, at this age, a 10-month-old will not look in the same direction as an adult if that adult's eyes are closed, a mistake that younger children make.[14] Initiation of joint attention begins at approximately 1 year old.[7] This might look like a child pointing to an airplane, then looking at their mom, and back at the airplane, as if to say "do you see that?" or "look at that!"

Joint attention is a critical social skill that drives development in other domains. Joint attention enables infants to identify objects that adults are labeling and promotes shared back-and-forth communication about them. Fifteen-month-old infants who were engaged in interactions with caregivers that include a joint attentional focus (e.g., a toy) demonstrated more frequent communicative utterances than when not in joint attention episodes.[15] These episodes of joint engagement were predictive of later vocabulary and word learning, especially when the joint attention was focused on an object that the infant was initially attending to,[15] such as when an infant picks up a ball, then the mother engages in a joint attention episode with the infant using the ball as the shared point of reference. At later ages, when initiating joint attention, the frequency that a child combines one word with a gesture (e.g., pointing to the plane and saying "plane") is associated with earlier onset of multi-word utterances, and more complex speech overall at 3.5 years old.[7]

Preschoolers (3–6 years old)

Self-concept

Self-concept refers to the set of attributes, abilities, attitudes, and values that one identifies as defining who he or she is.[7] Although some initial milestones occur before this period that support self-concept, including basic self awareness (i.e., the ability to recognize themselves in a mirror)[16] and self-labeling of their gender,[17] this period involves several advances in this domain. By 42 months, children are able to describe their likes and dislikes, suggesting a developing awareness of what elicits positive and negative emotions in themselves.[7] By 5 years old, children demonstrate agreement with their mothers' ratings of their behavior on basic behavioral indicators of personality.[7]

Gender identity

During the preschool period, children are deepening their gender identity and integrating gender socialization information into their self-concept.[17] Preschoolers learn gender stereotypes quickly and definitively, ranging from toy preferences, clothes, jobs, and behaviors. These stereotypes are initially held firmly, such that 3 to 4-year-olds will often state that violations are not possible and that they would not want to be friends with a child who violates their stereotypes.[7] Children acquire gender stereotypic behaviors early in the preschool period through social learning, then organize these behaviors into beliefs about themselves, forming a basic gender identity. By the end of the preschool period, children acquire gender constancy, an understanding of the biological basis of sex and its consistency over time.[7]

Understanding others

Younger preschool aged children demonstrate the basics of theory of mind, or the ability to take the perspective of others. However, this skill is constrained by children's limited understanding of how thoughts and beliefs, even when false, influence behavior.[7] This is demonstrated in the following scenario:

Danny puts his toy on the shelf, then leaves the room. His friend Sally comes in, plays with the toy, and puts it in the cabinet.

When asked where Danny will look for his toy, a young preschool aged child will state that he will look in the cabinet, therefore not recognizing Danny's current false belief about the toy's location. Between 4 and 6 years, children's capacity to understand false beliefs, and subsequently their accuracy in perspective taking, becomes strengthened.[18]

Social interactions

.jpg)

Play is often cited as a central building block to children's development, so much so that it has been stated as a human right of all children.[19] The complexity and diversity of play increases immensely in the preschool years, most notably with the onset of cooperative play, where children work toward a common goal, and socio-dramatic play (a type of cooperative play), where children act out make believe scenes.[7] Socio-dramatic play is rooted in the child's real-life experiences, falling into three categories: family scenes (e.g., "playing house" with assigned mommy and daddy roles), character scenes (e.g., being a superhero, or a princess), and functional scenes (e.g., playing doctor).[20] Cooperative play and socio-dramatic play both bring about increased social interactions, as compared to solitary play and parallel play, where children play similarly next to each other without significant interaction (e.g., two children building their own towers). It is here where play becomes intertwined with social emotional development. The characteristics of socio-dramatic play allow children to practice cooperation, negotiation, and conflict resolution skills, as well as engage in role-playing that promotes perspective taking. As such, socio-dramatic play has been associated with all of these social emotional skills in children.[20]

Middle childhood (7–12 years old)

Self-concept

Between 8–11 years old, children begin to use self-evaluations and competencies to define their sense of self.[7] This derives from the recently developed ability to make social comparisons. At 6 years old, these social comparisons may be to a specific individual; however, this becomes more complex in the coming years, allowing children to compare themselves and their performance to multiple individuals to arrive at a general conclusion.[7] School aged children also show the ability to simultaneously hold differentiated self-evaluations across domains (e.g., having good physical appearance, but poor school performance).[7]

Gender identity

In middle childhood, boys and girls form peer groups segregated by gender,[17] which may act to perpetuate previously learned gender stereotypes. Deriving from the ability to make social comparisons, school aged children begin to integrate attributions about how gender typical they are into their gender identity.[7] At this age, children's ability to make more global self-evaluations also allows them to recognize contentedness or dissonance with their gender assignment.[7] Children's gender identity on these two dimensions is significantly correlated with their self-esteem, such that children with higher levels of typicality and contentedness report having higher self-esteem and worth.[7]

Emotional experiences

Emotion vocabulary

By 3 years old, children have acquired a basic vocabulary for labeling simple emotional experiences, using words such as "scared," "happy," and "mad." However, the emotional vocabulary of children grows much more rapidly during middle childhood, doubling every two years in this period before slowing down dramatically in adolescence.[21] At the end of the preschool period, most children reliably comprehend the meaning of around 40 emotion words; by the time they are 11 years old, most children see a sevenfold increase to understanding almost 300 emotion words.[21][note 1]

Display rules

Emotional display rules are culturally bound norms that dictate when, how, and with whom individuals can express emotions. Accordingly, the ability to enact display rules relies on children's capacity for emotional expression and emotion regulation. Socialization toward these display rules begins in infancy, and children show some capacity in the preschool period. However, children's use of display rules and understanding of their value become increasingly complex in elementary school.[22] As children age from 1st to 7th grade, they are less likely to outwardly express anger or sadness.[23][24] Children also report using display rules to control their emotional expressions more with teachers than with peers,[24] and more than peers than with parents.[23] There is some evidence to suggest that this emotional masking also increases with age throughout the school age period, at least with teachers.[24] Display rules also inform how children choose to express emotions; as children move from the preschool period to middle childhood, they become more likely to use verbal communication to express negative emotions than nonverbal behaviors, such as crying or hitting.[7] Finally, at around 9 years old, bolstered by increased perspective taking skills, display rules are recognized as important to maintaining social harmony and relationships rather than simply a means to avoid punishment.[7]

Emotion regulation

Upon school entry, children's emotion regulation repertoire becomes increasingly diverse[25] as previously relied upon methods (e.g., seeking support from parents, moving away/avoiding an emotionally activating stimuli) become less effective. In middle childhood, children implement more complex distraction techniques, cognitive appraisal strategies (e.g., choosing to focus on the positive), and problem solving methods.[25] At 10 years old, children's emotion regulation involves a balance of problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping strategies.[7] Problem-focused coping represents a change driven strategy, focused on attempting to eliminate the source of stress through proactive action (e.g., if a child feels worried about a test, choosing to study to regulate that worry). In contrast, emotion-focused coping is acceptance based and can be more effective when the stressor can not be easily changed or removed (e.g., if a child is disappointed about their grade on the test, using strategies to reduce disappointment in the moment: "this will help me know what to study for the final").

And although diversification of emotion regulation strategy use occurs at this age, school aged children continue to strengthen their use of previous regulation strategies as well. Notably, school age children continue to seek out regulation support, but not just from their parents, but increasingly from teachers and peers in this period.[25] Children also show a developmental progression in differentiation of whom to go to for emotional support given then specific situations.[25] Thus on the whole, by the beginning of adolescence, children have been become more skilled emotion regulators on the whole.

Adolescence (13–18 years old)

Self-concept

Identity development

As adolescents navigate an increasingly diverse social world, their self-concept shifts to create and accommodate an organized understanding of how situational factors may influence their behavior (e.g., how and why behavior is different with friends as compared to with parents).[7] With this added complexity, a fundamental task of adolescence is considered forming a unified, coherent identity, inclusive of traits, values, and goals. Erik Erikson theorized that adolescence is characterized by a period of exploration and commitments. The combination of these two traits resulted in four identity statuses:[26]

- Identity achievement: a status characterized by a past period of exploration, and subsequent commitment to values and goals

- Moratorium: a status characterized by continued active exploration, without commitment

- Foreclosure: a status characterized by strong commitment to a prescribed identity (e.g., by teachers, parents), without a previous period of self exploration

- Diffusion: a status characterized by both a lack of exploration and a lack of commitment

Past research suggests that over the course of high school, the distribution of identity statuses changes, such that many adolescents begin high school in a Diffusion status, but many adolescents reach Identity Achievement status at the end of high school.[26] This general pattern is echoed in specific studies of minority group ethnic identity development, where youth initially have an unexplored ethnic identity, then enter a moratorium phase, followed by ethnic identity achievement.[27] In general, Identity Achievement and Moratorium statuses appear to be associated with positive psychological adjustment, including higher self-esteem, goal-oriented behavior, self-efficacy, and openness.[7]

Social interactions

Friendships

Adolescence is a time in which peer relationships become increasingly important and frequent. In this period, adolescents reliably spend approximately twice as much time with their peers than with their parents.[28] At the same time, there is a developmental shift occurring in the quality and nature of friendships in this period.[29] Adolescents' friendships are characterized by increased emotional support, intimacy, closeness, and loyalty. This is contrasted to friendships in early childhood, which is built upon time spent in joint activities, and middle childhood, which is defined by reciprocity and helping behavior.[7] Close friendships in adolescence can act as a buffer against the negative impacts of stressors, provide a foundation for intimacy and conflict resolution necessary in romantic relationships, and promote empathy for others.[7]

Peer acceptance

Peer acceptance is both related to children's prior social emotional development and predictive of later developments in this domain. Sociometric status identifies five classifications of peer acceptance in children based on two dimensions: social liking and social impact/visibility:[30] popular, average, rejected, neglected, and controversial. These patterns of acceptance can become self-perpetuating throughout childhood and adolescence, as rejected children are excluded from peer interactions that promote relationship skills, such as perspective taking and conflict resolution.[7]

Peer groups

During adolescence, children increasingly form peer groups, often with a common interest or values (e.g., "skaters," "jocks"), that are somewhat insular in nature (e.g., "cliques" or "crowds"). Theoretically, peer groups have been hypothesized to serve as an intermediary support source as adolescents exert independence from their family.[31] This is supported by data that indicates that the importance of peer group membership to youth increases in early adolescence, followed by a decline in later adolescence.[31][32]

Peers and peer groups at this age become important socialization agents, contributing to adolescents' sense of identity, behavior, and values.[28] Peer groups, whether intentionally or unintentionally, exert peer pressure and operant learning principles to shape behavior through reinforcement, resulting in members of peer groups become increasingly similar over time.[28] Many adolescents report the effects of peer influence on many aspects of their behavior, including academic engagement, risk-taking, and family involvement; however, the direction of this influence varied dependent on the peer group the adolescent was affiliated with.[28]

Assessment of social-emotional development

The assessment of social emotional development in young children must include an assessment of both child-level factors, such as genetic disorders, physical limitations, or linguistic and cognitive developmental level, as well as contextual factors, such as family and cultural factors.[33] Of particular importance for young children is the caregiving context, or the parent-child relationship.[33]

Early childhood Assessment

The majority of measures designed to assess early childhood social emotional development are parent report questionnaires. Parent reports using such measures repeatedly indicate that the 7%-12% of children show early social-emotional problems or delays.[33] Increasing evidence suggests that these problems remain moderately stable over periods of 1–2 years, suggesting clinical and societal benefits to early identification and intervention.[33] Standardized assessments have been developed to identify social emotional concerns as young as 6 months old.[34] Below is a list of some more widely used parent-report screening measures and comprehensive assessments:[33]

- Ages and Stages Questionnaire: Social Emotional (ASQ-SE)[34]

- Appropriate for children ages 6–60 months

- Screening measure: produces one score, with high scores indicating possible need for further evaluation

- Brief Infant and Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (BITSEA)[35]

- Appropriate for children ages 12–36 months

- Screening measure: produces Problem and Competence scores, combined cut-off point determines concern

- Child Behavior Checklist ages 1.5-5 (CBCL)[36]

- Appropriate for children ages 18 months – 60 months

- Comprehensive measure: produces specific DSM-oriented scale scores, as well as Internalizing, Externalizing, Total Problems standardized t-scores

Later Childhood Assessment

The Social Thinking Methodology is a developmental, language-based and thinking-based (metacognitive) methodology that uses visual frameworks, unique vocabulary, strategies, and activities to foster social competence for children ages 4 – 18 years old. The methodology has assessment and treatment components for both interventionists and social learners. The methodology includes components of other well-known and evidence based interventions such as Social Stories, Hidden Curriculum, 5-point scale, and others, etc. Social Thinking™ shares ideals with executive functioning, central coherence issues, and perspective-taking.

The assessment itself is multi-faceted, pulling information from a variety of sources and contexts. A thorough assessment of social skills includes: (a) observing the student with his peers and in different environmental contexts; (b) the diagnostician relating with the student without facilitating the student's social success; (c) a battery of informal assessment tools; (d) administering carefully considered standardized measures; (e) interviewing teachers and parents with regard to the students social cognition and social behaviors.[37]

Social emotional development in schools

Social and emotional learning in schools involves 5 key abilities: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making.[38] These skills are seen as the foundation upon which people can build all other relational skills. These core skills allow people to regulate and process emotions, think critically, maintain positive relationships, collaborate, and communicate effectively.[39] Social and emotional learning also has a clear connection with and is positively linked to academic success. It promotes active learning within a community setting, providing the emotional support many need to grow academically. Social and emotional learning recognizes that learning is a social activity and is most productive through collaboration.[38] Many child theorists stress the importance of learning as a social process in theories of child development. Vygotsky's developmental framework highlights the importance of children as social learners needing connections to learn and grow.[40]

Social emotional development in Latin America

In Mexico, efforts to promote social emotional development are challenged by the cultural stigma against mental health. Beginning in 2013, the Mexican government implemented programs of emotional pedagogy, like psicoeducacion, to raise self-knowledge and disseminate mental health information in many domains of public life in order to address this stigma.[41] Mexico's secretary of health defines pyschoeducacion as the teaching of expression, feelings, and behavior.[41] In Oaxaca, government-initiated psychoeducacion projects are common in health clinics, public health communications, as well as in the projects of nonprofit organizations.[42] Efforts have even been made to work with religious organizations to replace previous language for mental illness with more clinical terms.[42] The psychoeducacion trainings by the Mexican government, some of them mandatory, are aimed at teaching children the vocabulary to be able to express themselves in order to recognize the need for early treatment. Although cultural barriers exists the identification and management of emotions are treated as teachable skills.[43]

In the global mental health sector, there is concern that Western psychology is crowding out traditional understandings and treatments of mental illness, leading to some backlash against mental health care - such as, for example, amongst indigenous groups in Mexico.[44] To address this, some organizations advocate a close collaboration with indigenous communities.[45] Western experts are studying how specific terminology used in indigenous communities corresponds with common mental health syndromes recognized by the American Psychiatric Association.[46] By Western standards, the treatment and diagnosis of community "healers" is inconsistent and therefore devalued. Trained mental health experts express frustration, for example, towards those who wait until their symptoms are severe before seeking professional help.[42]

Notes

- Specifically, Baron-Cohen and colleagues found that 75% of 4- to 6-year-old children understood 41 out of 336 emotion words, and that by age 11, 75% of children understood 299 of these same words.[21]

References

- Cohen, J., Onunaku, N., Clothier, S., & Poppe, J. (2005). Helping young children succeed: Strategies to promote early childhood social and emotional development. In Research and Policy Report. Washington, DC: National Conference of State Legislatures.

- Benner, Gregory J.; Nelson, J. Ron; Epstein, Michael H. (2002). "Language Skills of Children with EBD". Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 10 (1): 43–56. doi:10.1177/106342660201000105. ISSN 1063-4266.

- Berking, Matthias; Wupperman, Peggilee (2012). "Emotion regulation and mental health". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 25 (2): 128–134. doi:10.1097/yco.0b013e3283503669. ISSN 0951-7367. PMID 22262030.

- Bruinsma, Yvonne; Koegel, Robert L.; Koegel, Lynn Kern (2004). "Joint attention and children with autism: A review of the literature". Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 10 (3): 169–175. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20036. ISSN 1080-4013. PMID 15611988.

- Baron-Cohen, Simon (2000), "Theory of mind and autism: A review", Autism, International Review of Research in Mental Retardation, 23, Elsevier, pp. 169–184, doi:10.1016/s0074-7750(00)80010-5, ISBN 9780123662231

- Bretherton, Inge (1992). "The origins of attachment theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth". Developmental Psychology. 28 (5): 759–775. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.28.5.759. ISSN 0012-1649.

- Berk, Laura (2013). Child Development, 9th Edition. New Jersey: Pearson. ISBN 978-0-205-14977-3.

- Waters, Everett; Cummings, E. Mark (2000). "A Secure Base from Which to Explore Close Relationships". Child Development. 71 (1): 164–172. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.505.6759. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00130. ISSN 0009-3920. PMID 10836570.

- Price., Tracy, Jessica L. Robins, Richard W. Tangney, June (2007). The self-conscious emotions : theory and research. Guilford Press. ISBN 9781593854867. OCLC 123029833.

- Cole, Pamela M.; Martin, Sarah E.; Dennis, Tracy A. (2004). "Emotion Regulation as a Scientific Construct: Methodological Challenges and Directions for Child Development Research". Child Development. 75 (2): 317–333. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.573.5887. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00673.x. ISSN 0009-3920. PMID 15056186.

- Sorce, James F.; Emde, Robert N.; Campos, Joseph J.; Klinnert, Mary D. (1985). "Maternal emotional signaling: Its effect on the visual cliff behavior of 1-year-olds". Developmental Psychology. 21 (1): 195–200. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.21.1.195. ISSN 0012-1649.

- "Emotional and Social Development: Birth to 3 Months". HealthyChildren.org. Retrieved 2018-11-26.

- Mundy, Peter; Newell, Lisa (2007). "Attention, Joint Attention, and Social Cognition". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 16 (5): 269–274. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00518.x. ISSN 0963-7214. PMC 2663908. PMID 19343102.

- Tomasello, Michael; Farrar, Michael Jeffrey (1986). "Joint Attention and Early Language". Child Development. 57 (6): 1454–63. doi:10.2307/1130423. ISSN 0009-3920. JSTOR 1130423. PMID 3802971.

- Rochat, Philippe (2003). "Five levels of self-awareness as they unfold early in life". Consciousness and Cognition. 12 (4): 717–731. doi:10.1016/s1053-8100(03)00081-3. ISSN 1053-8100. PMID 14656513.

- KATZ, PHYLLIS A. (1986), "Gender Identity: Development and Consequences", The Social Psychology of Female–Male Relations, Elsevier, pp. 21–67, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-065280-8.50007-5, ISBN 9780120652808

- Wellman, Henry M.; Cross, David; Watson, Julanne (2001). "Meta-Analysis of Theory-of-Mind Development: The Truth about False Belief". Child Development. 72 (3): 655–684. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00304. ISSN 0009-3920.

- Ginsburg, K. R. (2007-01-01). "The Importance of Play in Promoting Healthy Child Development and Maintaining Strong Parent-Child Bonds". Pediatrics. 119 (1): 182–191. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-2697. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 17200287.

- Ashiabi, Godwin S. (2007-04-17). "Play in the Preschool Classroom: Its Socioemotional Significance and the Teacher's Role in Play". Early Childhood Education Journal. 35 (2): 199–207. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.670.2322. doi:10.1007/s10643-007-0165-8. ISSN 1082-3301.

- Baron-Cohen, Simon; Golan, Ofer; Wheelwright, Sally; Granader, Yael; Hill, Jacqueline (2010). "Emotion Word Comprehension from 4 to 16 Years Old: A Developmental Survey". Frontiers in Evolutionary Neuroscience. 2: 109. doi:10.3389/fnevo.2010.00109. ISSN 1663-070X. PMC 2996255. PMID 21151378.

- Saarni, Carolyn (1979). "Children's understanding of display rules for expressive behavior". Developmental Psychology. 15 (4): 424–429. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.15.4.424. ISSN 0012-1649.

- Zeman, Janice; Garber, Judy (1996). "Display Rules for Anger, Sadness, and Pain: It Depends on Who Is Watching". Child Development. 67 (3): 957. doi:10.2307/1131873. ISSN 0009-3920. JSTOR 1131873.

- Underwood, Marion K.; Coie, John D.; Herbsman, Cheryl R. (1992). "Display Rules for Anger and Aggression in School-Age Children". Child Development. 63 (2): 366–380. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01633.x. ISSN 0009-3920.

- Zimmer-Gembeck, Melanie J.; Skinner, Ellen A. (2010-12-21). "Review: The development of coping across childhood and adolescence: An integrative review and critique of research". International Journal of Behavioral Development. 35 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1177/0165025410384923. hdl:10072/43249. ISSN 0165-0254.

- Waterman, Alan S. (1982). "Identity development from adolescence to adulthood: An extension of theory and a review of research". Developmental Psychology. 18 (3): 341–358. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.18.3.341. ISSN 0012-1649.

- Phinney, Jean S. (1989). "Stages of Ethnic Identity Development in Minority Group Adolescents". The Journal of Early Adolescence. 9 (1–2): 34–49. doi:10.1177/0272431689091004. ISSN 0272-4316.

- Ryan, Allison M. (2000). "Peer Groups as a Context for the Socialization of Adolescents' Motivation, Engagement, and Achievement in School". Educational Psychologist. 35 (2): 101–111. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep3502_4. ISSN 0046-1520.

- Bukowski, William M.; Hoza, Betsy; Boivin, Michel (1993). "Popularity, friendship, and emotional adjustment during early adolescence". New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 1993 (60): 23–37. doi:10.1002/cd.23219936004. ISSN 1520-3247.

- Newcomb, Andrew F.; Bukowski, William M.; Pattee, Linda (1993). "Children's peer relations: A meta-analytic review of popular, rejected, neglected, controversial, and average sociometric status". Psychological Bulletin. 113 (1): 99–128. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.113.1.99. ISSN 0033-2909.

- Brown, B. Bradford; Eicher, Sue Ann; Petrie, Sandra (1986). "The importance of peer group ("crowd") affiliation in adolescence". Journal of Adolescence. 9 (1): 73–96. doi:10.1016/s0140-1971(86)80029-x. ISSN 0140-1971. PMID 3700780.

- Crockett, Lisa; Losoff, Mike; Petersen, Anne C. (1984). "Perceptions of the Peer Group and Friendship in Early Adolescence". The Journal of Early Adolescence. 4 (2): 155–181. doi:10.1177/0272431684042004. ISSN 0272-4316.

- Carter, Alice S.; Briggs-Gowan, Margaret J.; Davis, Naomi Ornstein (2004). "Assessment of young children's social-emotional development and psychopathology: recent advances and recommendations for practice". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 45 (1): 109–134. doi:10.1046/j.0021-9630.2003.00316.x. ISSN 0021-9630. PMID 14959805.

- Squires, J.; Bricker, D.; Twombly, E. (2002). The ASQ:SE user's guide: For the Ages & Stages Questionnaires: Social-emotional. Baltimore, MD, US: Paul H Brookes Publishing.

- Briggs-Gowan, M. J. (2004-03-01). "The Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment: Screening for Social-Emotional Problems and Delays in Competence". Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 29 (2): 143–155. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsh017. ISSN 0146-8693.

- Achenbach, Thomas M.; Rescorla., Leslie A. (2000). Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms and profiles. Vol. 30. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research center for children, youth, & families.

- Winner, Michelle Garcia (2015-02-10). "Assessment of Social Cognition and Related Skills". socialthinking.com. Retrieved September 2019. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Oberle, E., & Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2017). Social and Emotional Learning: Recent Research and Practical Strategies for Promoting Children’s Social and Emotional Competence in Schools. Handbook of Social Behavior and Skills in Children, 175–197. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-64592-6_11

- Woolfolk, Anita, et al. Human Development, Learning and Diversity 2015-2016: Third Custom Edition for the University of British Columbia/Adapted by Work from Anita Woolfolk, Nancy E. Perry, Teresa M. McDevitt and Jeanne Ellis Ormrod. Access and Diversity, Crane Library, University of British Columbia, 2016.

- John-Steiner, Vera, and Seana Moran. "Vygotsky’s contemporary contribution to the dialectic of development and creativity." Creativity and development (2003): 61-90.

- Salud, Secretaría de. "Programa de Acción Específico - Salud Mental 2013-2018". gob.mx (in Spanish). Retrieved 2020-05-13.

- Duncan, Whitney L. (2017). "Psicoeducación in the land of magical thoughts: Culture and mental-health practice in a changing Oaxaca". American Ethnologist. 44 (1): 36–51. doi:10.1111/amet.12424. ISSN 1548-1425.

- Wilce, James M.; Fenigsen, Janina (June 2016). "Emotion Pedagogies: What Are They, and Why Do They Matter?: EMOTION PEDAGOGIES". Ethos. 44 (2): 81–95. doi:10.1111/etho.12117.

- Pan American Health Organization (May 2016). "Promoting Mental Health in Indigenous Populations. Experiences from Countries. A collaboration between PAHO/WHO, Canada, Chile and Partners from the Region of the Americas 2014-2015". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Cohen, Alex; Kleinman, Arthur; Saraceno, Benedetto, eds. (2002). "World Mental Health Casebook". doi:10.1007/b112400. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Smith, Bryce D.; Sabin, Miriam; Berlin, Elois Ann; Nackerud, Larry (September 2009). "Ethnomedical Syndromes and Treatment-Seeking Behavior among Mayan Refugees in Chiapas, Mexico". Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 33 (3): 366–381. doi:10.1007/s11013-009-9145-3. ISSN 0165-005X.