Emotional reasoning

Emotional reasoning is a cognitive process by which an individual concludes that their emotional reaction proves something is true, despite contrary empirical evidence. Emotional reasoning creates an 'emotional truth', which may be in direct conflict with the inverse 'perceptional truth'.[1] It can create feelings of anxiety, fear, and apprehension in existing stressful situations, and as such, is often associated with or triggered by panic disorder or anxiety disorder.[2] For example, even though a spouse has shown only devotion, a person using emotional reasoning might conclude, "I know my spouse is being unfaithful because I feel jealous."

This process amplifies the effects of other cognitive distortions. For example, a student may feel insecure about their understanding of test material even though they are capable of answering the questions. If said student acts on their insecurity about failing the test, they might make the assumption that they misunderstand the material and therefore may guess answers randomly, causing their own failure in a self-fulfilling prophecy.[3]

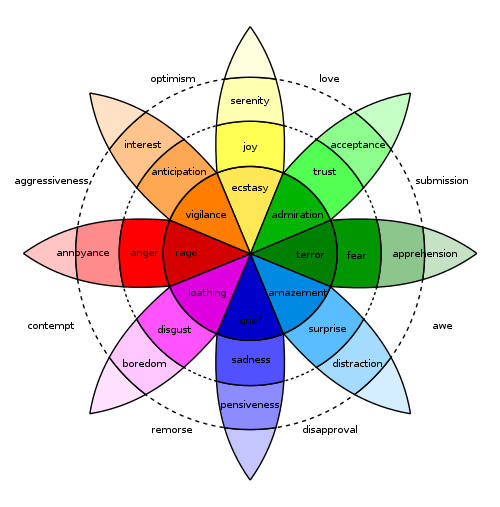

Emotional reasoning is related to other similar concepts such as motivated reasoning, a type of reasoning wherein individuals reach conclusions from bias instead of empirical motivations;[4] emotional intelligence, which relates to the ways in which individuals use their emotions to understand situations or the information and reach conclusions;[5] and cognitive distortion or cognitive deficiency, wherein individuals misinterpret situations or make decisions without considering a range of consequences.[6]

Origin

| Part of a series on |

| Psychology |

|---|

|

|

Emotional reasoning, as a concept, was first introduced by psychiatrist Aaron Beck.[7] It was included as a part of Beck's broader research topic: cognitive distortions and depression. To counteract cognitive distortions, Beck developed a type of therapy formally known as cognitive therapy, which became associated with cognitive-behavioral therapy.[8] Originally, emotional reasoning was attributed to automatic thinking. Beck believed that emotional reasoning stemmed from negative thoughts that were uncontrollable and happened without effort.[8] This reasoning has been commonly accepted over the years. Most recently, a new explanation states that an "activating agent" or sensory trigger from the environment increases emotional arousal.[9] With this increase in arousal, certain areas of the brain are inhibited.[9] The combination of an increase in emotional arousal and the inhibition of parts of the brain leads to emotional reasoning.[9]

Treatment

Before seeking professional help, an individual can influence the effect that emotional reasoning has on them based on his or her coping method. Using a proactive, problem-focused coping style is more effective at reducing stress and deterring stressful events.[10] Additionally, having good social support also leads to lower psychological stress.[10] If one has to seek professional help, the most common therapy method is cognitive-behavioral therapy. In this approach, the automatic thoughts that control emotional reasoning are studied and realistically reasoned by the patient.[7] In doing so, the psychologist hopes to change the automatic thoughts of the patient and reduce his/her stress levels.[7] Cognitive behavioral therapy has been generally regarded as the most effective method of treatment for emotional reasoning.

Most recently, a new therapeutic approach uses the RIGAAR method to reduce emotional stress.[11] RIGAAR stands for:[11]

- Rapport building

- Information gathering

- Goal setting

- Accessing resources

- Agreeing strategies

- Rehearsing success

Additionally, reducing emotional arousal is also suggested by the human givens approach as a way to stop emotional reasoning.[9] As seen above, high emotional arousal inhibits brain regions necessary for logical complex reasoning. With less emotional arousal, cognitive reasoning is not diminished and the potential to not associate oneself with his or her emotions is stronger.

Factors

Cognitive schemas is one of the factors to cause emotional reasoning. Schema is made of how we look at this world and our real-life experiences. Schema helps us remember the important things or events that happened in our lives. The result of the learning process is the schema, and it is also made by classical and operant conditioning. For example, an individual can develop a schema about terrorists and spiders that are very dangerous. People can change what they think or they are biased about the way they perceive things based on their schema. Information-processing biases make schema impact how a person thinks, memory, or their understanding of experiences and information. The bias makes a person’s schema automatically access to similar content of schema. For example, a person with rat phobia; they are more likely to see and are aware of the rat is near them. Schemes are also easily making the connection with schema-central stimuli. For example, when depressed people start to think about negative things, it would be really hard for them to stop thinking about it.[12]

For memory bias, schema can mix up an individual’s memory to cause schema-incongruent memories. For example, if individuals have a schema about how intelligent they are, failure-related recollections have a high chance to stick in their minds and unlikely to flash on positive events that happened in the past. The schema also makes individuals biased through the way they interpret information. In other words, schema tricks their understanding of the information. For example, when people refuse to help low self-esteem children solve the math problem, this causes the children to think they are too stupid to learn how to solve math problems instead of thinking about those people who are too busy to help them out.[12]

Techniques for reducing emotional reasoning

Validity testing: Patients defend their thoughts and ideas, and they are supposed to bring up objective evidence to support their assumptions. If not, they might be exposed to emotional reasoning.[13]

Cognitive reversal: Patients told of a difficult situation that they had in the past, and they work with a therapist to help them fix practicing their problems. Thus, the patient could know how to face and fix difficult situations instead of reverting to emotional reasoning.[13]

Guided discovery: The therapist asks the patients a series of questions designed to help patients realize their cognition distortions.[13]

Writing in a journal: Patients form a habit of writing in a journal to record the situations they face, emotions, thoughts they have, and their responses or behaviors to them in their daily life. The therapist and patient will analyze how their maladaptive thought patterns influence their behaviors together.[13]

Homework: The patient can acquire the ability to do self-recovery and remember the insights that they gain from therapy sessions, and the therapist would ask patients to write down the note during the session or read the books about the therapy. Doing so, they could be more focused on their thoughts and behaviors and record the outcomes for the next therapy session.[13]

Modeling: The therapist could use role-playing to act in different ways to respond to difficult situations so patients could understand and model the behavior.[13]

Systematic positive reinforcement: Positive reinforcement can reinforce the human’s behavior. In other words, if humans get the reward from anyone or anything for the first time, they are more likely to do it again in the future. The behavior-oriented therapist would use a reward system (systematic positive reinforcement) to motivate patients to reinforce specific behaviors.[13]

Negative memories from the past and stressful life circumstances at the present have a chance to trigger depression. The main factor for causing depression is unresolved life experiences. People who do emotional reasoning are more likely to connect to depression. Emotion-Focused Therapy (EFT) is a form of psychotherapy and another way to help people find a positive side for their emotional process. EFT is the research-based treatment, and it emphasizes emotional change and is also the goal of therapy. EFT has two different alternative therapies for treatments. One is cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), which emphasizes changing self-defeating thoughts and behaviors. Another is interpersonal therapy (IPT), which emphasizes changing people’s skills to have better interaction with others.[14]

From EFT’s viewpoint, a person’s development is influenced by emotional memories and experiences. The purpose of therapy is to change the emotional process by resurfacing painful emotional experiences and bringing them into awareness. This process helps patients to recognize between what they experience is at present and how the past experiences influence how they feel at the moment. Thus, they are more likely to know what they want in their life and make better decisions for everything, and their emotional process is less likely to include emotional reasoning. Another purpose of therapy is to promote emotional intelligence - the ability to understand their emotions and perceive emotional information to fix problems and control their behavior.[14]

Emotion-focused coping is a way to focus on managing one’s emotions to reduce stress and also to reduce the chance to have emotional reasoning.[15] Cognitive therapy is a form of therapy that helps patients recognize their negative thought patterns about themselves and events to revise these thought patterns and change their behavior. [16] Cognitive-behavioral therapy helps individuals to do well on cognitive tasks and to help them rethink their situation in a way that can benefit them.[17] The treatment of cognitive-behavioral therapy is through the process of learning and making the change for maladaptive emotions, thoughts, and behaviors.[18]

Implications

If not treated, debilitating effects can occur, the most common being depression.[19] On the other hand, emotional reasoning has the potential to be good when used to appraise the outside world and not ourselves. It is useful when one has to emotionally appraise something. Judging by how one feels when assessing the object, person, or event, it can be an instinctual survival response and a way to adapt to our world.[20] "The amygdala buried deep in the limbic system serves as an early warning device for novelty, precisely so that attention can be mobilized to alert the mind to potential danger and to prepare for a potential of flight or fight."[21]

See also

References

- de Sousa, Ronald; Morton, Adam (2002). "Emotional Truth". Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, Supplementary Volumes. 76. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- Cooper, Peter J.; Alkozei, Anna; Creswell, Cathy (January 2014). "Emotional reasoning and anxiety sensitivity: Associations with social anxiety disorder in childhood". Journal of Affective Disorders. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.09.014.

- Brophy, Jere E. (July 1982). "Research on the Self-fulfilling Prophecy and Teacher Expectations" (PDF). Michigan State University Research on Teaching. Michigan State University. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- Pandelaere, M. 2007. "Motivated Reasoning." Pp. 595–97 in Encyclopedia of Social Psychology 2, edited by R. F. Baumeister and K. D. Vohs. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Brackett, M. A., and P. Salovey. 2007. "Emotional Intelligence." Pp. 293–94 in Encyclopedia of Social Psychology 1, edited by R. F. Baumeister and K. D. Vohs. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Forman, S. G. 2005. "Cognitive–Behavioral Modification." Pp. 95–98 in Encyclopedia of School Psychology, edited by S. W. Lee. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- "Frequently asked questions". Beck Institute for Cognitive Behavior Therapy. 2011-09-19. Archived from the original on September 7, 2015.

- "The History of Cognitive Therapy". Beck Institute for Cognitive Behavior Therapy. Archived from the original on December 14, 2011.

- Shona Adams. "Human Givens Theory of Cognitive Distortions" (PDF). Archived from the original on 2015-10-10.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Taylor, Shelley E.; Stanton, Annette L. (April 2007). "Coping Resources, Coping Processes, and Mental Health". Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 3 (1): 377–401. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091520. PMID 17716061.

- Linda Hoggan, Carmen Kane (2008). "Just what we need" (PDF). Human Givens Journal. 15 (2).CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Cognitive Schemas." Pp. 391–93 in The SAGE Encyclopedia of Lifespan Human Development 1, edited by M. H. Bornstein. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. 2018.

- Ford-Martin, P. 2003. "Cognitive-behavioral therapy." Pp. 226–28 in The Gale Encyclopedia of Mental Disorders 1, edited by M. Harris and E. Thackerey. Thousand Oaks, Detroit, MI: Gale.

- Andrews, L. W. 2010. "Emotion-Focused Therapy." Pp. 183–85 in Encyclopedia of Depression 1. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Press.

- Bornstein, M. H.,ed. 2018. "Emotion-Focused Coping." Pp. 730–32 in The SAGE Encyclopedia of Lifespan Human Development 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Reference.

- Cognitive Therapy. (2016). In J. L. Longe (Ed.), The Gale Encyclopedia of Psychology (3rd ed., Vol. 1, pp. 215-217). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale. Retrieved from https://link-gale-com.byui.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/CX3631000151/GVRL?u=byuidaho&sid=GVRL&xid=76946d80

- Schmidt, R. F., and W. D. Willis, eds. 2018. "Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy." Encyclopedia of Pain. Berlin: Springer. p. 408.

- Lewin, M. R. 2006. "Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy." Pp. 104–06 in Encyclopedia of Multicultural Psychology, edited by Y. Jackson. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Reference.

- Knaus, William (1 June 2012). The Cognitive Behavioral Workbook for Depression: A Step-by-Step Program (Second ed.). New Harbinger Publications. p. 255.

- Lazarus, Richard (11 April 1996). Passion and Reason: Making Sense of our Emotions. Oxford University Press. p. 3.

- Kellogg, Ronald (16 July 2013). The Making of the Mind: The Neuroscience of Human Nature. Prometheus Books. p. 176.