Emotional intelligence

Emotional intelligence (EI), emotional leadership (EL), emotional quotient (EQ) and emotional intelligence quotient (EIQ), is the capability of individuals to recognize their own emotions and those of others, discern between different feelings and label them appropriately, use emotional information to guide thinking and behavior, and manage and/or adjust emotions to adapt to environments or achieve one's goal(s).[1][2]

Although the term first appeared in 1964,[3] it gained popularity in the 1995 book "Emotional Intelligence", written by the science journalist Daniel Goleman.[4]

Empathy is typically associated with EI, because it relates to an individual connecting their personal experiences with those of others. However, several models exist that aim to measure levels of (empathy) EI. There are currently several models of EI. Goleman's original model may now be considered a mixed model that combines what has since been modeled separately as ability EI and trait EI. Goleman defined EI as the array of skills and characteristics that drive leadership performance.[5] The trait model was developed by Konstantinos V. Petrides in 2001. It "encompasses behavioral dispositions and self perceived abilities and is measured through self report".[6] The ability model, developed by Peter Salovey and John Mayer in 2004, focuses on the individual's ability to process emotional information and use it to navigate the social environment.[7]

Studies have shown that people with high EI have greater mental health, job performance, and leadership skills although no causal relationships have been shown and such findings are likely to be attributable to general intelligence and specific personality traits rather than emotional intelligence as a construct. For example, Goleman indicated that EI accounted for 67% of the abilities deemed necessary for superior performance in leaders, and mattered twice as much as technical expertise or IQ.[8] Other research finds that the effect of EI markers on leadership and managerial performance is non-significant when ability and personality are controlled for,[9] and that general intelligence correlates very closely with leadership.[10] Markers of EI and methods of developing it have become more widely coveted in the past decade by individuals seeking to become more effective leaders. In addition, studies have begun to provide evidence to help characterize the neural mechanisms of emotional intelligence.[11][12][13][14]

Criticisms have centered on whether EI is a real intelligence and whether it has incremental validity over IQ and the Big Five personality traits.[15]

History

The term "emotional intelligence" seems first to have appeared in a 1964 paper by Michael Beldoch,[16][17] and in the 1966 paper by B. Leuner entitled Emotional intelligence and emancipation which appeared in the psychotherapeutic journal: Practice of child psychology and child psychiatry.[18]

In 1983, Howard Gardner's Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences[19] introduced the idea that traditional types of intelligence, such as IQ, fail to fully explain cognitive ability. He introduced the idea of multiple intelligences which included both interpersonal intelligence (the capacity to understand the intentions, motivations and desires of other people) and intrapersonal intelligence (the capacity to understand oneself, to appreciate one's feelings, fears and motivations).[20]

The term subsequently appeared in Wayne Payne's doctoral thesis, A Study of Emotion: Developing Emotional Intelligence in 1985.[21]

The first published use of the term 'EQ' (Emotional Quotient) is an article by Keith Beasley in 1987 in the British Mensa magazine.[22]

In 1989 Stanley Greenspan put forward a model to describe EI, followed by another by Peter Salovey and John Mayer published in the following year.[23]

However, the term became widely known with the publication of Goleman's book: Emotional Intelligence – Why it can matter more than IQ[24] (1995). It is to this book's best-selling status that the term can attribute its popularity.[25][26] Goleman has followed up with several further popular publications of a similar theme that reinforce use of the term.[27][28][29][30][31] To date, tests measuring EI have not replaced IQ tests as a standard metric of intelligence.[32] Emotional Intelligence has also received criticism on its role in leadership and business success.[33]

The distinction between trait emotional intelligence and ability emotional intelligence was introduced in 2000.[34]

Definitions

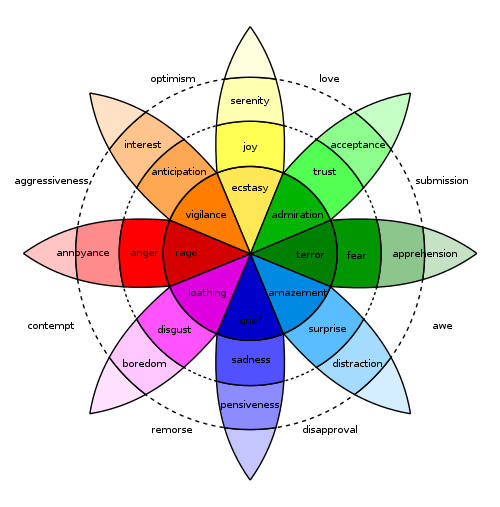

Emotional intelligence has been defined, by Peter Salovey and John Mayer, as "the ability to monitor one's own and other people's emotions, to discriminate between different emotions and label them appropriately, and to use emotional information to guide thinking and behavior". This definition was later broken down and refined into four proposed abilities: perceiving, using, understanding, and managing emotions. These abilities are distinct yet related.[1] Emotional intelligence also reflects abilities to join intelligence, empathy and emotions to enhance thought and understanding of interpersonal dynamics.[35] However, substantial disagreement exists regarding the definition of EI, with respect to both terminology and operationalizations. Currently, there are three main models of EI:

Different models of EI have led to the development of various instruments for the assessment of the construct. While some of these measures may overlap, most researchers agree that they tap different constructs.

Specific ability models address the ways in which emotions facilitate thought and understanding. For example, emotions may interact with thinking and allow people to be better decision makers (Lyubomirsky et al. 2005).[35] A person who is more responsive emotionally to crucial issues will attend to the more crucial aspects of his or her life.[35] Aspects of emotional facilitation factor is to also know how to include or exclude emotions from thought depending on context and situation.[35] This is also related to emotional reasoning and understanding in response to the people, environment and circumstances one encounters in his or her day-to-day life.[35]

Ability model

Salovey and Mayer's conception of EI strives to define EI within the confines of the standard criteria for a new intelligence.[38][39] Following their continuing research, their initial definition of EI was revised to "The ability to perceive emotion, integrate emotion to facilitate thought, understand emotions and to regulate emotions to promote personal growth." However, after pursuing further research, their definition of EI evolved into "the capacity to reason about emotions, and of emotions, to enhance thinking. It includes the abilities to accurately perceive emotions, to access and generate emotions so as to assist thought, to understand emotions and emotional knowledge, and to reflectively regulate emotions so as to promote emotional and intellectual growth." [7]

The ability-based model views emotions as useful sources of information that help one to make sense of and navigate the social environment.[40][41] The model proposes that individuals vary in their ability to process information of an emotional nature and in their ability to relate emotional processing to a wider cognition. This ability is seen to manifest itself in certain adaptive behaviors. The model claims that EI includes four types of abilities:

- Perceiving emotions – the ability to detect and decipher emotions in faces, pictures, voices, and cultural artifacts—including the ability to identify one's own emotions. Perceiving emotions represents a basic aspect of emotional intelligence, as it makes all other processing of emotional information possible.

- Using emotions – the ability to harness emotions to facilitate various cognitive activities, such as thinking and problem-solving. The emotionally intelligent person can capitalize fully upon his or her changing moods in order to best fit the task at hand.

- Understanding emotions – the ability to comprehend emotion language and to appreciate complicated relationships among emotions. For example, understanding emotions encompasses the ability to be sensitive to slight variations between emotions, and the ability to recognize and describe how emotions evolve over time.

- Managing emotions – the ability to regulate emotions in both ourselves and in others. Therefore, the emotionally intelligent person can harness emotions, even negative ones, and manage them to achieve intended goals.

The ability EI model has been criticized in the research for lacking face and predictive validity in the workplace.[42] However, in terms of construct validity, ability EI tests have great advantage over self-report scales of EI because they compare individual maximal performance to standard performance scales and do not rely on individuals' endorsement of descriptive statements about themselves.[43]

Measurement

The current measure of Mayer and Salovey's model of EI, the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) is based on a series of emotion-based problem-solving items.[41][44] Consistent with the model's claim of EI as a type of intelligence, the test is modeled on ability-based IQ tests. By testing a person's abilities on each of the four branches of emotional intelligence, it generates scores for each of the branches as well as a total score.

Central to the four-branch model is the idea that EI requires attunement to social norms. Therefore, the MSCEIT is scored in a consensus fashion, with higher scores indicating higher overlap between an individual's answers and those provided by a worldwide sample of respondents. The MSCEIT can also be expert-scored so that the amount of overlap is calculated between an individual's answers and those provided by a group of 21 emotion researchers.[41]

Although promoted as an ability test, the MSCEIT is unlike standard IQ tests in that its items do not have objectively correct responses. Among other challenges, the consensus scoring criterion means that it is impossible to create items (questions) that only a minority of respondents can solve, because, by definition, responses are deemed emotionally "intelligent" only if the majority of the sample has endorsed them. This and other similar problems have led some cognitive ability experts to question the definition of EI as a genuine intelligence.[45]

In a study by Føllesdal,[46] the MSCEIT test results of 111 business leaders were compared with how their employees described their leader. It was found that there were no correlations between a leader's test results and how he or she was rated by the employees, with regard to empathy, ability to motivate, and leader effectiveness. Føllesdal also criticized the Canadian company Multi-Health Systems, which administers the MSCEIT test. The test contains 141 questions but it was found after publishing the test that 19 of these did not give the expected answers. This has led Multi-Health Systems to remove answers to these 19 questions before scoring but without stating this officially.

Other measurements

Various other specific measures have also been used to assess ability in emotional intelligence. These measures include:

- Diagnostic Analysis of Non-verbal Accuracy[35] – The Adult Facial version includes 24 photographs of equal amount of happy, sad, angry, and fearful facial expressions of both high and low intensities which are balanced by gender. The tasks of the participants is to answer which of the four emotions is present in the given stimuli.[35]

- Japanese and Caucasian Brief Affect Recognition test[35] – Participants try to identify 56 faces of Caucasian and Japanese individuals expressing seven emotions such happiness, contempt, disgust, sadness, anger, surprise, and fear, which may also trail off for 0.2 seconds to a different emotion.[35]

- Levels of Emotional Awareness Scale[35] – Participants reads 26 social scenes and answers their anticipated feelings and continuum of low to high emotional awareness.[35]

Mixed model

The model introduced by Daniel Goleman[47] focuses on EI as a wide array of competencies and skills that drive leadership performance. Goleman's model outlines five main EI constructs (for more details see "What Makes A Leader" by Daniel Goleman, best of Harvard Business Review 1998):

- Self-awareness – the ability to know one's emotions, strengths, weaknesses, drives, values and goals and recognize their impact on others while using gut feelings to guide decisions.

- Self-regulation – involves controlling or redirecting one's disruptive emotions and impulses and adapting to changing circumstances.

- Social skill – managing relationships to get along with others

- Empathy – considering other people's feelings especially when making decisions

- Motivation – being aware of what motivates them.

Goleman includes a set of emotional competencies within each construct of EI. Emotional competencies are not innate talents, but rather learned capabilities that must be worked on and can be developed to achieve outstanding performance. Goleman posits that individuals are born with a general emotional intelligence that determines their potential for learning emotional competencies.[48] Goleman's model of EI has been criticized in the research literature as mere "pop psychology" (Mayer, Roberts, & Barsade, 2008).

Measurement

Two measurement tools are based on the Goleman model:

- The Emotional Competency Inventory (ECI), which was created in 1999, and the Emotional and Social Competency Inventory (ESCI), a newer edition of the ECI was developed in 2007. The Emotional and Social Competency – University Edition (ESCI-U) is also available. These tools developed by Goleman and Boyatzis provide a behavioral measure of the Emotional and Social Competencies.

- The Emotional Intelligence Appraisal, which was created in 2001 and which can be taken as a self-report or 360-degree assessment.[49]

Trait model

Konstantinos V. Petrides ("K. V. Petrides") proposed a conceptual distinction between the ability based model and a trait based model of EI and has been developing the latter over many years in numerous publications.[34][50] Trait EI is "a constellation of emotional self-perceptions located at the lower levels of personality."[50] In lay terms, trait EI refers to an individual's self-perceptions of their emotional abilities. This definition of EI encompasses behavioral dispositions and self-perceived abilities and is measured by self report, as opposed to the ability based model which refers to actual abilities, which have proven highly resistant to scientific measurement. Trait EI should be investigated within a personality framework.[51] An alternative label for the same construct is trait emotional self-efficacy.

The trait EI model is general and subsumes the Goleman model discussed above. The conceptualization of EI as a personality trait leads to a construct that lies outside the taxonomy of human cognitive ability. This is an important distinction in as much as it bears directly on the operationalization of the construct and the theories and hypotheses that are formulated about it.[34]

Measurement

There are many self-report measures of EI,[52] including the EQ-i, the Swinburne University Emotional Intelligence Test (SUEIT), and the Schutte EI model. None of these assess intelligence, abilities, or skills (as their authors often claim), but rather, they are limited measures of trait emotional intelligence.[50] The most widely used and widely researched measure of self-report or self-schema (as it is currently referred to) emotional intelligence is the EQ-i 2.0. Originally known as the BarOn EQ-i, it was the first self-report measure of emotional intelligence available, the only measure predating Goleman's best-selling book. There are over 200 studies that have used the EQ-i or EQ-i 2.0. It has the best norms, reliability, and validity of any self-report instrument and was the first one reviewed in the Buros Mental Measures Book. The EQ-i 2.0 is available in many different languages as it is used worldwide.

The TEIQue provides an operationalization for the model of Konstantinos V. Petrides and colleagues, that conceptualizes EI in terms of personality.[53] The test encompasses 15 subscales organized under four factors: well-being, self-control, emotionality, and sociability. The psychometric properties of the TEIQue were investigated in a study on a French-speaking population, where it was reported that TEIQue scores were globally normally distributed and reliable.[54]

The researchers also found TEIQue scores were unrelated to nonverbal reasoning (Raven's matrices), which they interpreted as support for the personality trait view of EI (as opposed to a form of intelligence). As expected, TEIQue scores were positively related to some of the Big Five personality traits (extraversion, agreeableness, openness, conscientiousness) as well as inversely related to others (alexithymia, neuroticism). A number of quantitative genetic studies have been carried out within the trait EI model, which have revealed significant genetic effects and heritabilities for all trait EI scores.[55] Two recent studies (one a meta-analysis) involving direct comparisons of multiple EI tests yielded very favorable results for the TEIQue.[37][56]

General effects

A review published in the journal of Annual Psychology found that higher emotional intelligence is positively correlated with:[35]

- Better social relations for children – Among children and teens, emotional intelligence positively correlates with good social interactions, relationships and negatively correlates with deviance from social norms, anti-social behavior measured both in and out of school as reported by children themselves, their own family members as well as their teachers.[35]

- Better social relations for adults – High emotional intelligence among adults is correlated with better self-perception of social ability and more successful interpersonal relationships while less interpersonal aggression and problems.[35]

- Highly emotionally intelligent individuals are perceived more positively by others – Other individuals perceive those with high EI to be more pleasant, socially skilled and empathic to be around.[35]

- Better family and intimate relationships – High EI is correlated with better relationships with the family and intimate partners on many aspects.

- Better academic achievement – Emotional intelligence is correlated with greater achievement in academics as reported by teachers but generally not higher grades once the factor of IQ is taken into account.[35]

- Better social relations during work performance and in negotiations – Higher emotional intelligence is correlated with better social dynamics at work as well as better negotiating ability.[35]

- Better psychological well-being - Emotional intelligence is positively correlated with higher life satisfaction, self-esteem and lower levels of insecurity or depression. It is also negatively correlated with poor health choices and behavior.[35]

- Allows for self-compassion - Emotionally intelligent individuals are more likely to have a better understanding of themselves and to make conscious decisions based on emotion and rationale combined. Overall, it leads a person to self-actualization.[57]

Criticisms

EI, and Goleman's original 1995 analysis, have been criticized within the scientific community,[58] despite prolific reports of its usefulness in the popular press.[59][60][61][62]

Predictive power

Landy[63] distinguishes between the "commercial wing" and "the academic wing" of the EI movement, basing this distinction on the alleged predictive power of EI as seen by the two currents. According to Landy, the former makes expansive claims on the applied value of EI, while the latter is trying to warn users against these claims. As an example, Goleman (1998) asserts that "the most effective leaders are alike in one crucial way: they all have a high degree of what has come to be known as emotional intelligence. ...emotional intelligence is the sine qua non of leadership". In contrast, Mayer (1999) cautions "the popular literature's implication—that highly emotionally intelligent people possess an unqualified advantage in life—appears overly enthusiastic at present and unsubstantiated by reasonable scientific standards." Landy further reinforces this argument by noting that the data upon which these claims are based are held in "proprietary databases", which means they are unavailable to independent researchers for reanalysis, replication, or verification.[63] Furthermore, Murensky (2000) states it is difficult to create objective measures of emotional intelligence and demonstrate its influence on leadership as many scales are self-report measures.[64]

In an academic exchange, Antonakis and Ashkanasy/Dasborough mostly agreed that researchers testing whether EI matters for leadership have not done so using robust research designs; therefore, currently there is no strong evidence showing that EI predicts leadership outcomes when accounting for personality and IQ.[65] Antonakis argued that EI might not be needed for leadership effectiveness (he referred to this as the "curse of emotion" phenomenon, because leaders who are too sensitive to their and others' emotional states might have difficulty making decisions that would result in emotional labor for the leader or followers). A recently published meta-analysis seems to support the Antonakis position: In fact, Harms and Credé found that overall (and using data free from problems of common source and common methods), EI measures correlated only ρ = 0.11 with measures of transformational leadership.[66] Barling, Slater, and Kelloway (2000) also support Harms and Crede’s position on transformational leadership.[67] Barling et al. found that transformational leadership (chiefly employing idealized influence, inspirational motivation and individualized consideration) as well as contingent rewards are associated with emotional intelligence and transformational leadership skills. Thus, some research shows that individuals higher in EI are seen as exhibiting more leadership behaviors. Together, Harms and Crede as well as Barling et al., demonstrate emotional intelligence may have an important role on transformational leadership in the workplace and that if EI can be developed perhaps certain transformational leadership behaviors can be too. Ability-measures of EI fared worst (i.e., ρ = 0.04); the WLEIS (Wong-Law measure) did a bit better (ρ = 0.08), and the Bar-On[68] measure better still (ρ = 0.18). However, the validity of these estimates does not include the effects of IQ or the big five personality, which correlate both with EI measures and leadership.[69] In a subsequent paper analyzing the impact of EI on both job performance and leadership, Harms and Credé[70] found that the meta-analytic validity estimates for EI dropped to zero when Big Five traits and IQ were controlled for. Joseph and Newman[71] meta-analytically showed the same result for Ability EI.

However, self-reported and Trait EI measures retain a fair amount of predictive validity for job performance after controlling Big Five traits and IQ.[71] Newman, Joseph, and MacCann[72] contend that the greater predictive validity of Trait EI measures is due to their inclusion of content related to achievement motivation, self efficacy, and self-rated performance. Meta-analytic evidence confirms that self-reported emotional intelligence predicting job performance is due to mixed EI and trait EI measures' tapping into self-efficacy and self-rated performance, in addition to the domains of Neuroticism, Extraversion, Conscientiousness, and IQ. As such, the predictive ability of mixed EI to job performance drops to nil when controlling for these factors.[73] Rosete and Ciarrochi (2005) also explored the predictive ability of EI and job performance.[74] They concluded that higher EI was associated with higher leadership effectiveness regarding achievement of organizational goals. Their study shows EI may serve an identifying tool in understanding who is (or is not) likely to deal effectively with colleagues. Furthermore, there exists the ability to develop and enhance leadership qualities through the advancement of one's emotional intelligence. Groves, McEnrue, and Shen (2008) found EI can be deliberately developed, specifically facilitating thinking with emotions (FT) and monitoring and regulation of emotions (RE) in the workplace.[75] The treatment group in their study demonstrated statistically significant overall EI gains, while the control group did not.[76]

Correlation with personality

Similarly, other researchers have raised concerns about the extent to which self-report EI measures correlate with established personality dimensions. Generally, self-report EI measures and personality measures have been said to converge because they both purport to measure personality traits.[50] Specifically, there appear to be two dimensions of the Big Five that stand out as most related to self-report EI – neuroticism and extraversion. In particular, neuroticism has been said to relate to negative emotionality and anxiety. Intuitively, individuals scoring high on neuroticism are likely to score low on self-report EI measures.

Studies have examined the multivariate effects of personality and intelligence on EI and also attempted to correct estimates for measurement error. For example, a study by Schulte, Ree, Carretta (2004),[77] showed that general intelligence (measured with the Wonderlic Personnel Test), agreeableness (measured by the NEO-PI), as well as gender could reliably be used to predict the measure of EI ability. They gave a multiple correlation (R) of .81 with the MSCEIT (perfect prediction would be 1). This result has been replicated by Fiori and Antonakis (2011),;[78] they found a multiple R of .76 using Cattell’s "Culture Fair" intelligence test and the Big Five Inventory (BFI); significant covariates were intelligence (standardized beta = .39), agreeableness (standardized beta = .54), and openness (standardized beta = .46). Antonakis and Dietz (2011a),[79] who investigated the Ability Emotional Intelligence Measure found similar results (Multiple R = .69), with significant predictors being intelligence, standardized beta = .69 (using the Swaps Test and a Wechsler scales subtest, the 40-item General Knowledge Task) and empathy, standardized beta = .26 (using the Questionnaire Measure of Empathic Tendency). Antonakis and Dietz (2011b) also show how including or excluding important controls variables can fundamentally change results.

Interpretations of the correlations between EI questionnaires and personality have been varied., but a prominent view in the scientific literature is the Trait EI view, which re-interprets EI as a collection of personality traits.[80][81][82]

Socially desirable responding

Socially desirable responding (SDR), or "faking good", is defined as a response pattern in which test-takers systematically represent themselves with an excessive positive bias (Paulhus, 2002). This bias has long been known to contaminate responses on personality inventories (Holtgraves, 2004; McFarland & Ryan, 2000; Peebles & Moore, 1998; Nichols & Greene, 1997; Zerbe & Paulhus, 1987), acting as a mediator of the relationships between self-report measures (Nichols & Greene, 1997; Gangster et al., 1983).

It has been suggested that responding in a desirable way is a response set, which is a situational and temporary response pattern (Pauls & Crost, 2004; Paulhus, 1991). This is contrasted with a response style, which is a more long-term trait-like quality. Considering the contexts some self-report EI inventories are used in (e.g., employment settings), the problems of response sets in high-stakes scenarios become clear (Paulhus & Reid, 2001).

There are a few methods to prevent socially desirable responding on behavior inventories. Some researchers believe it is necessary to warn test-takers not to fake good before taking a personality test (e.g., McFarland, 2003). Some inventories use validity scales in order to determine the likelihood or consistency of the responses across all items.

EI as behavior rather than intelligence

Goleman's early work has been criticized for assuming from the beginning that EI is a type of intelligence or cognitive ability. Eysenck (2000)[83] writes that Goleman's description of EI contains unsubstantiated assumptions about intelligence in general and that it even runs contrary to what researchers have come to expect when studying types of intelligence:

"[Goleman] exemplifies more clearly than most the fundamental absurdity of the tendency to class almost any type of behavior as an 'intelligence'... If these five 'abilities' define 'emotional intelligence', we would expect some evidence that they are highly correlated; Goleman admits that they might be quite uncorrelated, and in any case, if we cannot measure them, how do we know they are related? So the whole theory is built on quicksand: there is no sound scientific basis."

Similarly, Locke (2005)[84] claims that the concept of EI is in itself a misinterpretation of the intelligence construct, and he offers an alternative interpretation: it is not another form or type of intelligence, but intelligence—the ability to grasp abstractions—applied to a particular life domain: emotions. He suggests the concept should be re-labeled and referred to as a skill.

The essence of this criticism is that scientific inquiry depends on valid and consistent construct utilization and that before the introduction of the term EI, psychologists had established theoretical distinctions between factors such as abilities and achievements, skills and habits, attitudes and values, and personality traits and emotional states.[85] Thus, some scholars believe that the term EI merges and conflates such accepted concepts and definitions.

EI as skill rather than moral quality

Adam Grant warned of the common but mistaken perception of EI as a desirable moral quality rather than a skill.[86] Grant asserted that a well-developed EI is not only an instrumental tool for accomplishing goals, but can function as a weapon for manipulating others by robbing them of their capacity to reason.[86]

EI as a measure of conformity

One criticism of the works of Mayer and Salovey comes from a study by Roberts et al. (2001),[87] which suggests that the EI, as measured by the MSCEIT, may only be measuring conformity. This argument is rooted in the MSCEIT's use of consensus-based assessment, and in the fact that scores on the MSCEIT are negatively distributed (meaning that its scores differentiate between people with low EI better than people with high EI).

EI as a form of knowledge

Further criticism has been leveled by Brody (2004),[88] who claimed that unlike tests of cognitive ability, the MSCEIT "tests knowledge of emotions but not necessarily the ability to perform tasks that are related to the knowledge that is assessed". The main argument is that even though someone knows how he or she should behave in an emotionally laden situation, it doesn't necessarily follow that the person could actually carry out the reported behavior.

NICHD pushes for consensus

The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development has recognized that because there are divisions about the topic of emotional intelligence, the mental health community needs to agree on some guidelines to describe good mental health and positive mental living conditions. In their section, "Positive Psychology and the Concept of Health", they explain. "Currently there are six competing models of positive health, which are based on concepts such as being above normal, character strengths and core virtues, developmental maturity, social-emotional intelligence, subjective well-being, and resilience. But these concepts define health in philosophical rather than empirical terms. Dr. [Lawrence] Becker suggested the need for a consensus on the concept of positive psychological health...".[89]

Interactions with other phenomena

Bullying

Bullying is abusive social interaction between peers which can include aggression, harassment, and violence. Bullying is typically repetitive and enacted by those who are in a position of power over the victim. A growing body of research illustrates a significant relationship between bullying and emotional intelligence.[90][91][92] They also have shown that emotional intelligence is a key factor in the analysis of cases of cybervictimization,[93] by demonstrating a relevant impact on health and social adaptation.

Emotional intelligence (EI) is a set of abilities related to the understanding, use and management of emotion as it relates to one's self and others. Mayer et al., (2008) defines the dimensions of overall EI as: "accurately perceiving emotion, using emotions to facilitate thought, understanding emotion, and managing emotion".[94] The concept combines emotional and intellectual processes.[95] Lower emotional intelligence appears to be related to involvement in bullying, as the bully and/or the victim of bullying. EI seems to play an important role in both bullying behavior and victimization in bullying; given that EI is illustrated to be malleable, EI education could greatly improve bullying prevention and intervention initiatives.[96]

Job performance

The most recent meta-analysis of emotional intelligence and job performance showed correlations of r=.20 (for job performance & ability EI) and r=.29 (for job performance and mixed EI).[73] Earlier research on EI and job performance had shown mixed results: a positive relation has been found in some of the studies, while in others there was no relation or an inconsistent one.[73] This led researchers Cote and Miners (2006)[97] to offer a compensatory model between EI and IQ, that posits that the association between EI and job performance becomes more positive as cognitive intelligence decreases, an idea first proposed in the context of academic performance (Petrides, Frederickson, & Furnham, 2004). The results of the former study supported the compensatory model: employees with low IQ get higher task performance and organizational citizenship behavior directed at the organization, the higher their EI. It has also been observed that there is no significant link between emotional intelligence and work attitude-behavior.[98]

A more recent study suggests that EI is not necessarily a universally positive trait.[99] They found a negative correlation between EI and managerial work demands; while under low levels of managerial work demands, they found a negative relationship between EI and teamwork effectiveness. An explanation for this may suggest gender differences in EI, as women tend to score higher levels than men.[71] This furthers the idea that job context plays a role in the relationships between EI, teamwork effectiveness, and job performance. Another find was discussed in a study that assessed a possible link between EI and entrepreneurial behaviors and success.[100]

Although studies between emotional intelligence (EI) and job performance have shown mixed results of high and low correlations, EI is an undeniably better predictor than most of the hiring methods commonly used in companies, such as letter of references, cover letter, among others. By 2008, 147 companies and consulting firms in U.S had developed programmes that involved EI for training and hiring employees.[101] Van Rooy and Viswesvaran (2004)[102] showed that EI correlated significantly with different domains in performance, ranging from .24 for job performance to .10 for academic performance. These findings may contribute to organizations in different ways. For instance, employees high on EI would be more aware of their own emotions and from others, which in turn, could lead companies to better profits and less unnecessary expenses. This is especially important for expatriate managers, who have to deal with mixed emotions and feelings, while adapting to a new working culture.[102] Moreover, employees high in EI show more confidence in their roles, which allow them to face demanding tasks positively.[103]

According to a popular science book by the journalist Daniel Goleman, emotional intelligence accounts for more career success than IQ.[104] Similarly, other studies argued that employees high on EI perform substantially better than employees low in EI. This is measured by self-reports and different work performance indicators, such as wages, promotions and salary increase.[105] According to Lopes and his colleagues (2006),[106] EI contributes to develop strong and positive relationships with co-workers and perform efficiently in work teams. This benefits performance of workers by providing emotional support and instrumental resources needed to succeed in their roles.[107] Also, emotionally intelligent employees have better resources to cope with stressing situations and demanding tasks, which enable them to outperform in those situations.[106] For instance, Law et al. (2004)[105] found that EI was the best predictor of job performance beyond general cognitive ability among IT scientists in computer company in China. Similarly, Sy, Tram, and O’Hara (2006)[103] found that EI was associated positively with job performance in employees from a food service company.[108]

In the job performance – emotional intelligence correlation is important to consider the effects of managing up, which refers to the good and positive relationship between the employee and his/her supervisor.[109] Previous research found that quality of this relationship could interfere in the results of the subjective rating of job performance evaluation.[110] Emotionally intelligent employees devote more of their working time on managing their relationship with supervisors. Hence, the likelihood of obtaining better results on performance evaluation is greater for employees high in EI than for employees with low EI.[103] Based on theoretical and methodological approaches, EI measures are categorized in three main streams: (1) stream 1: ability-based measures (e.g. MSCEIT), (2) stream 2: self-reports of abilities measures (e.g. SREIT, SUEIT and WLEIS) and (3) stream 3: mixed-models (e.g. AES, ECI, EI questionnaire, EIS, EQ-I and GENOS), which include measures of EI and traditional social skills.[111] O’Boyle Jr. and his colleagues (2011)[112] found that the three EI streams together had a positive correlation of 0.28 with job performance. Similarly, each of EI streams independently obtained a positive correlation of 0.24, 0.30 and 0.28, respectively. Stream 2 and 3 showed an incremental validity for predicting job performance over and above personality (Five Factor model) and general cognitive ability. Both, stream 2 and 3 were the second most important predictor of job performance below general cognitive ability. Stream 2 explained 13.6% of the total variance; whereas stream 3, explained 13.2%. In order to examine the reliability of these findings, a publication bias analysis was developed. Results indicated that studies on EI-job performance correlation prior to 2010 do not present substantial evidences to suggest the presence of publication bias. Noting that O'Boyle Jr. et al. (2011) had included self-rated performance and academic performance in their meta-analysis, Joseph, Jin, Newman, & O'Boyle (2015) collaborated to update the meta-analysis to focus specifically on job performance; using measures of job performance, these authors showed r=.20 (for job performance & ability EI) and r=.29 (for job performance and mixed EI).[73]

Despite the validity of previous findings, some researchers still question whether EI – job performance correlation makes a real impact on business strategies. They argue that the popularity of EI studies is due to media advertising, rather than objective scientific findings.[97] Also, it is mentioned that the relationship between job performance and EI is not as strong as suggested. This relationship requires the presence of other constructs to raise important outcomes. For instance, previous studies found that EI is positively associated with teamwork effectiveness under job contexts of high managerial work demands, which improves job performance. This is due to the activation of strong emotions during the performance on this job context. In this scenario, emotionally intelligent individuals show a better set of resources to succeed in their roles. However, individuals with high EI show a similar level of performance than non-emotionally intelligent employees under different job contexts.[113] Moreover, Joseph and Newman (2010)[114] suggested that emotional perception and emotional regulation components of EI highly contribute to job performance under job contexts of high emotional demands. Moon and Hur (2011)[115] found that emotional exhaustion (“burn-out”) significantly influences the job performance – EI relationship. Emotional exhaustion showed a negative association with two components of EI (optimism and social skills). This association impacted negatively to job performance, as well. Hence, job performance – EI relationship is stronger under contexts of high emotional exhaustion or burn-out; in other words, employees with high levels of optimism and social skills possess better resources to outperform when facing high emotional exhaustion contexts.

Leadership

There are several studies that attempt to study the relationship between EI and leadership. Although EI does play a positive role when it comes to leadership effectiveness, what actually makes a leader effective is what he/she does with his role, rather than his interpersonal skills and abilities. Although in the past a good or effective leader was the one who gave orders and controlled the overall performance of the organization, almost everything is different nowadays: leaders are now expected to motivate and create a sense of belongingness that will make employees feel comfortable, thus, making them work more effectively.[116]

However, this does not mean that actions are more important than emotional intelligence. Leaders still need to grow emotionally in order to handle different problems of stress, and lack of life balance, among other things.[117] A proper way to grow emotionally, for instance, is developing a sense of empathy since empathy is a key factor when it comes to emotional intelligence. In a study conducted to analyze the relationship between School Counselors' EI and leadership skills, it was concluded that several participants were good leaders because their emotional intelligence was developed in counselor preparations, where empathy is taught.[118]

Health

A 2007 meta-analysis of 44 effect sizes by Schutte found that emotional intelligence was associated with better mental and physical health. Particularly, trait EI had the stronger association with mental and physical health.[119] This was replicated again in 2010 by researcher Alexandra Martin who found trait EI as a strong predictor for health after conducting a meta-analysis based on 105 effect sizes and 19,815 participants. This meta-analysis also indicated that this line of research reached enough sufficiency and stability in concluding EI as a positive predictor for health.[120]

An earlier study by Mayer and Salovsky argued that high EI can increase one's own well-being because of its role in enhancing relationships.[121]

Self-esteem and drug dependence

A 2012 study cross-examined emotional intelligence, self-esteem and marijuana dependence.[122] Out of a sample of 200, 100 of whom were dependent on cannabis and the other 100 emotionally healthy, the dependent group scored exceptionally low on EI when compared to the control group. They also found that the dependent group also scored low on self-esteem when compared to the control.

Another study in 2010 examined whether or not low levels of EI had a relationship with the degree of drug and alcohol addiction.[123] In the assessment of 103 residents in a drug rehabilitation center, they examined their EI along with other psychosocial factors in a one-month interval of treatment. They found that participants' EI scores improved as their levels of addiction lessened as part of their treatment.

See also

- Anabel Jensen

- Claude Steiner

- Emotional literacy

- Emotional thought method

- Four Cornerstone Model of Emotional Intelligence

- Joshua Freedman

- Life skills

- Marc Brackett

- Outline of human intelligence

- People skills

- Positive psychology

- Religiosity and emotional intelligence

- Psychological mindedness

- Soft skills

References

- Colman, Andrew (2008). A Dictionary of Psychology (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199534067.

- "Chapter 2 EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE : AN OVERVIEW" (PDF). INFLIBNET Centre. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- In "The Communication of Emotional Meaning" paper by a member of Department of Psychology Teachers at College Columbia University Joel Robert Davitz and clinical professor of psychology in psychiatry Michael Beldoch. Davitz, Joel Robert; Beldoch, Michael (1976). The communication of emotional meaning. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. OCLC 647368022.

- Popularity Graph by Google Ngram Viewer. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- Goleman, Daniel (1998), What Makes a Leader?, Harvard Business Review

- Petrides, Konstantin; Furnham, Adrian (2001), "Trait Emotional Intelligence: Psychometric Investigation with Reference to Established Trait Taxonomies", European Journal of Personality, pp. 425–448

- Salovey, Peter; Mayer, John; Caruso, David (2004), "Emotional Intelligence: Theory, Findings, and Implications", Psychological Inquiry, pp. 197–215

- Goleman, D. (1998). Working With Emotional Intelligence. New York, NY. Bantum Books.

- Cavazotte, Flavia; Moreno, Valter; Hickmann, Mateus (2012). "Effects of leader intelligence, personality and emotional intelligence on transformational leadership and managerial performance". The Leadership Quarterly. 23 (3): 443–455. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.10.003.

- Atwater, Leanne; Yammarinol, Francis (1993). "Personal attributes as predictors of superiors' and subordinates' perceptions of military academy leadership". Human Relations. 46 (5): 645–668. doi:10.1177/001872679304600504.

- Barbey, Aron K.; Colom, Roberto; Grafman, Jordan (2012). "Distributed neural system for emotional intelligence revealed by lesion mapping". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 9 (3): 265–272. doi:10.1093/scan/nss124. PMC 3980800. PMID 23171618.

- Yates, Diana. "Researchers Map Emotional Intelligence in the Brain". University of Illinois News Bureau. University of Illinois. Archived from the original on 2014-08-13.

- "Scientists Complete 1st Map of 'Emotional Intelligence' in the Brain". US News and World Report. 2013-01-28. Archived from the original on 2014-08-14.

- Kosonogov, Vladimir; Vorobyeva, Elena; Kovsh, Ekaterina; Ermakov, Pavel (2019). "A review of neurophysiological and genetic correlates of emotional intelligence" (PDF). International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education. 7 (1): 137–142. doi:10.5937/IJCRSEE1901137K. ISSN 2334-847X.

- Harms, P. D.; Credé, M. (2010). "Remaining Issues in Emotional Intelligence Research: Construct Overlap, Method Artifacts, and Lack of Incremental Validity". Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice. 3 (2): 154–158. doi:10.1111/j.1754-9434.2010.01217.x.

- Beldoch, M. (1964), Sensitivity to expression of emotional meaning in three modes of communication, in J. R. Davitz et al., The Communication of Emotional Meaning, McGraw-Hill, pp. 31–42

- "Contributions to social interactions: Social Encounters" Archived 2017-09-05 at the Wayback Machine Editor: Michael Argyle, reprint online on Google Books

- Leuner, B (1966). "Emotional intelligence and emancipation". Praxis der Kinderpsychologie und Kinderpsychiatrie. 15: 193–203.

- Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind. New York: Basic Books.

- Smith, M.K. (2002). "Howard Gardner, multiple intelligences and education". The Encyclopedia of Informal Education. Archived from the original on 2005-11-02. Retrieved 2005-11-01.

- Payne, W.L. (1983/1986). A study of emotion: developing emotional intelligence; self integration; relating to fear, pain and desire" Dissertation Abstracts International 47, p. 203A (University microfilms No. AAC 8605928)

- Beasley, K. (1987). The Emotional Quotient. Mensa, May 1987, p25. http://www.keithbeasley.co.uk/EQ/Original%20EQ%20article.pdf

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J.D. (1989). "Emotional intelligence". Imagination, Cognition, and Personality. 9 (3): 185–211. doi:10.2190/dugg-p24e-52wk-6cdg.

- Goleman, D., (1995) Emotional Intelligence, New York, NY, England: Bantam Books, Inc.

- "Dan Goleman". Huffingtonpost.com. Archived from the original on 2014-03-04. Retrieved 2014-03-07.

- Dan Schawbel. "Daniel Goleman on Leadership and The Power of Emotional Intelligence – Forbes". Archived from the original on 2012-11-04. Retrieved 2014-03-07.

- Goleman, D. (1998), Working with Emotional Intelligence

- Goleman, D. (2006), Social Intelligence: The New Science of Human Relationships

- Lantieri, L. and Goleman, D. (2008), Building Emotional Intelligence: Techniques to Cultivate Inner Strength in Children

- Goleman, D. (2011), The Brain and Emotional Intelligence: New Insights

- Goleman, D. (2011), Leadership: The Power of Emotional Intelligence

- "What is Emotional Intelligence and How to Improve it? (Definition + EQ Test)". positivepsychologyprogram.com. 14 November 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- "Why emotional intelligence is just a fad – CBS News". 2012-02-13. Archived from the original on 2012-11-28. Retrieved 2014-03-07.

- Petrides, K.V.; Furnham, A. (2000a). "On the dimensional structure of emotional intelligence". Personality and Individual Differences. 29 (2): 313–320. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.475.5285. doi:10.1016/s0191-8869(99)00195-6.

- Mayer, John D (2008). "Human Abilities: Emotional Intelligence". Annual Review of Psychology. 59: 507–536. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093646. PMID 17937602. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22.

- Kluemper, D.H. (2008). "Trait emotional intelligence: The impact of core-self evaluations and social desirability". Personality and Individual Differences. 44 (6): 1402–1412. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.12.008.

- Martins, A.; Ramalho, N.; Morin, E. (2010). "A comprehensive meta-analysis of the relationship between emotional intelligence and health". Journal of Personality and Individual Differences. 49 (6): 554–564. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.05.029.

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P.; Caruso, D.L.; Sitarenios, G. (2001). "Emotional intelligence as a standard intelligence". Emotion. 1 (3): 232–242. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.1.3.232.

- MacCann, C.; Joseph, D.L.; Newman, D.A.; Roberts, R.D. (2014). "Emotional intelligence is a second-stratum factor of intelligence: Evidence from hierarchical and bifactor models". Emotion. 14 (2): 358–374. doi:10.1037/a0034755. PMID 24341786.

- Mayer, J.D., & Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey & D. Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Implications for educators (pp. 3–31). New York: Basic Books.

- Salovey, P; Grewal, D (2005). "The Science of Emotional Intelligence". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 14 (6): 6. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00381.x.

- Bradberry, T.; Su, L. (2003). "Ability-versus skill-based assessment of emotional intelligence" (PDF). Psicothema. 18: 59–66. PMID 17295959. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-09-05. Retrieved 2014-03-07.

- Brackett M.A. & J.D. Mayer, M.A. & J.D. (2003). "Convergent, discriminant, and incremental validity of competing measures of emotional intelligence". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 29 (9): 1147–1158. doi:10.1177/0146167203254596. PMID 15189610.

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P.; Caruso, D.R.; Sitarenios, G. (2003). "Measuring emotional intelligence with the MSCEIT V2.0". Emotion. 3 (1): 97–105. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.3.1.97. PMID 12899321.

- K.V. Petrides, "Ability and Trait Emotional Intelligence", in The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Individual Differences, ed. Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, Sophie von Stumm, and Adrian Furnham (London: John Wiley & Sons, 2015), 656-78. ISBN 1119050308, 9781119050308

- Hallvard Føllesdal. "Emotional Intelligence as Ability: Assessing the Construct Validity of Scores from the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT)". PhD Thesis and accompanying papers – University of Oslo 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-12-16.

- Goleman, D. (1998). Working with emotional intelligence. New York: Bantam Books

- Boyatzis, R., Goleman, D., & Rhee, K. (2000). Clustering competence in emotional intelligence: insights from the emotional competence inventory (ECI). In R. Bar-On & J.D.A. Parker (eds.): Handbook of emotional intelligence (pp. 343–362). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Bradberry, Travis and Greaves, Jean. (2009). Emotional Intelligence 2.0. San Francisco: Publishers Group West. ISBN 978-0-9743206-2-5

- Petrides, K.V.; Pita, R.; Kokkinaki, F. (2007). "The location of trait emotional intelligence in personality factor space". British Journal of Psychology. 98 (2): 273–289. doi:10.1348/000712606x120618. PMID 17456273.

- Petrides, K.V.; Furnham, A. (2001). "Trait emotional intelligence: Psychometric investigation with reference to established trait taxonomies". European Journal of Personality. 15 (6): 425–448. doi:10.1002/per.416.

- Pérez, J.C., Petrides, K.V., & Furnham, A. (2005). Measuring trait emotional intelligence. In R. Schulze and R.D. Roberts (Eds.), International Handbook of Emotional Intelligence (pp.181–201). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Hogrefe & Huber.

- Petrides, K.V.; Furnham, A. (2003). "Trait emotional intelligence: behavioral validation in two studies of emotion recognition and reactivity to mood induction". European Journal of Personality. 17: 39–75. doi:10.1002/per.466.

- Mikolajczak, Luminet; Leroy; Roy (2007). "Psychometric Properties of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire: Factor Structure, Reliability, Construct, and Incremental Validity in a French-Speaking Population". Journal of Personality Assessment. 88 (3): 338–353. doi:10.1080/00223890701333431. PMID 17518555.

- Vernon, P.A.; Petrides, K.V.; Bratko, D.; Schermer, J.A. (2008). "A behavioral genetic study of trait emotional intelligence". Emotion. 8 (5): 635–642. doi:10.1037/a0013439. PMID 18837613.

- Gardner, J. K.; Qualter, P. (2010). "Concurrent and incremental validity of three trait emotional intelligence measures". Australian Journal of Psychology. 62: 5–12. doi:10.1080/00049530903312857.

- Heffernan, Mary; Quinn, Mary; McNulty, Rita; Fitzpatrick, Joyce (2010). "Self-compassion and emotional intelligence in nurses". International Journal of Nursing Practice. 16 (4): 366–373. doi:10.1111/j.1440-172X.2010.01853.x. PMID 20649668. S2CID 1902234.

- Murphy, Kevin R. A critique of emotional intelligence: what are the problems and how can they be fixed?. Psychology Press, 2014.

- Article at Harvard Business Review 9 January 2017 Archived 2 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine accessed 30 January 2017

- Article at Huffington Post 20 July 2016 Archived 2 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine accessed 30 January 2017

- Article at "psychcentral.com" 30 October 2015 Archived 2 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine accessed 30 January 2017

- "How good is your EQ" at "thehindu.com" 6 December 2015 Archived 3 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine accessed 30 January 2017

- Landy, F.J. (2005). "Some historical and scientific issues related to research on emotional intelligence". Journal of Organizational Behavior. 26 (4): 411–424. doi:10.1002/job.317.

- Murensky, Catherine Lynn (2000). "The relationships between emotional intelligence, personality, critical thinking ability and organizational leadership performance at upper levels of management". Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering – via PsyNET.

- Antonakis, J.; Ashkanasy, N. M.; Dasborough, M. (2009). "Does leadership need emotional intelligence?". The Leadership Quarterly. 20 (2): 247–261. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.01.006.

- Harms, P. D.; Credé, M. (2010). "Emotional Intelligence and Transformational and Transactional Leadership: A Meta-Analysis". Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies. 17 (1): 5–17. doi:10.1177/1548051809350894. Archived from the original on 2011-06-12.

- Barling, Julian; Slater, Frank; Kevin Kelloway, E. (May 2000). "Transformational leadership and emotional intelligence: an exploratory study". Leadership & Organization Development Journal. 21 (3): 157–161. doi:10.1108/01437730010325040. ISSN 0143-7739.

- Bar-On, R (2006). "The Bar-On model of emotional-social intelligence (ESI)". Psicothema. 18: 13–25. PMID 17295953.

- Antonakis, J. (2009). ""Emotional intelligence": What does it measure and does it matter for leadership?" (PDF). In G. B. Graen (ed.). LMX leadership—Game-Changing Designs: Research-Based Tools. VII. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing. pp. 163–192. Download article: ""Emotional intelligence": What does it measure and does it matter for leadership?" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2010-09-06.

- Harms, P. D.; Credé, M. (2010). "Remaining Issues in Emotional Intelligence Research: Construct Overlap, Method Artifacts, and Lack of Incremental Validity". Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice. 3 (2): 154–158. doi:10.1111/j.1754-9434.2010.01217.x.

- Joseph, D. L.; Newman, D. A. (2010). "Emotional Intelligence: An Integrative Meta-Analysis and Cascading Model". Journal of Applied Psychology. 95 (1): 54–78. doi:10.1037/a0017286. PMID 20085406.

- Newman, D. A.; Joseph, D. L.; MacCann, C. (2010). "Emotional Intelligence and Job Performance: The Importance of Emotion Regulation and Emotional Labor Context". Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice. 3 (2): 159–164. doi:10.1111/j.1754-9434.2010.01218.x.

- Joseph, D.L.; Jin, J.; Newman, D.A.; O'Boyle, E.H. (2015). "Why Does Self-Reported Emotional Intelligence Predict Job Performance? A Meta-Analytic Investigation of Mixed EI". Journal of Applied Psychology. 100 (2): 298–342. doi:10.1037/a0037681. PMID 25243996.

- Ciarrochi, Joseph; Rosete, David (2005-07-01). "Emotional intelligence and its relationship to workplace performance outcomes of leadership effectiveness". Leadership & Organization Development Journal. 26 (5): 388–399. doi:10.1108/01437730510607871. ISSN 0143-7739.

- Shen, Winny; Groves, Kevin S.; Pat McEnrue, Mary (2008-02-08). "Developing and measuring the emotional intelligence of leaders". Journal of Management Development. 27 (2): 225–250. doi:10.1108/02621710810849353. ISSN 0262-1711.

- Slater, Frank; Barling, Julian; Kevin Kelloway, E. (2000-05-01). "Transformational leadership and emotional intelligence: an exploratory study". Leadership & Organization Development Journal. 21 (3): 157–161. doi:10.1108/01437730010325040. ISSN 0143-7739.

- Schulte, M. J.; Ree, M. J.; Carretta, T. R. (2004). "Emotional intelligence: Not much more than g and personality". Personality and Individual Differences. 37 (5): 1059–1068. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2003.11.014.

- Fiori, M.; Antonakis, J. (2011). "The ability model of emotional intelligence: Searching for valid measures". Personality and Individual Differences (Submitted manuscript). 50 (3): 329–334. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.10.010.

- Antonakis, J.; Dietz, J. (2011a). "Looking for Validity or Testing It? The Perils of Stepwise Regression, Extreme-Scores Analysis, Heteroscedasticity, and Measurement Error". Personality and Individual Differences (Submitted manuscript). 50 (3): 409–415. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.09.014.

- Mikolajczak, M.; Luminet, O.; Leroy, C.; Roy, E. (2007). "Psychometric properties of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire". Journal of Personality Assessment. 88 (3): 338–353. doi:10.1080/00223890701333431. PMID 17518555.

- Smith, L.; Ciarrochi, J.; Heaven, P. C. L. (2008). "The stability and change of trait emotional intelligence, conflict communication patterns, and relationship satisfaction: A one-year longitudinal study". Personality and Individual Differences. 45 (8): 738–743. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2008.07.023.

- Austin, E.J. (2008). "A reaction time study of responses to trait and ability emotional intelligence test items" (PDF). Personality and Individual Differences. 46 (3): 381–383. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2008.10.025.

- Eysenck, H.J. (2000). Intelligence: A New Look. ISBN 978-0-7658-0707-6.

- Locke, E.A. (2005). "Why emotional intelligence is an invalid concept". Journal of Organizational Behavior. 26 (4): 425–431. doi:10.1002/job.318.

- Mattiuzzi, P.G. (2008) Emotional Intelligence? I'm not feeling it. Archived 2009-07-20 at the Wayback Machine everydaypsychology.com

- Grant, Adam (January 2, 2014). "The Dark Side of Emotional Intelligence". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on January 3, 2014.

- Roberts, R.D.; Zeidner, M.; Matthews, G. (2001). "Does emotional intelligence meet traditional standards for an intelligence? Some new data and conclusions". Emotion. 1 (3): 196–231. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.1.3.196. PMID 12934681.

- Brody, N (2004). "What cognitive intelligence is and what emotional intelligence is not" (PDF). Psychological Inquiry. 15 (3): 234–238. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli1503_03. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-02-07.

- Nitkin, Ralph; Harris, Meredith (August 29, 2006). "National Advisory Board on Medical Rehabilitation Research: Meeting for Minutes for December 2–3, 2004". National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Archived from the original on July 16, 2009. Retrieved April 24, 2017.

- Lamb, Jennifer; Pepler, Debra J.; Craig, Wendy (2009-04-01). "Approach to bullying and victimization". Canadian Family Physician. 55 (4): 356–360. ISSN 0008-350X. PMC 2669002. PMID 19366941.

- Kokkinos, Constantinos M.; Kipritsi, Eirini (2011-07-26). "The relationship between bullying, victimization, trait emotional intelligence, self-efficacy and empathy among preadolescents". Social Psychology of Education. 15 (1): 41–58. doi:10.1007/s11218-011-9168-9. ISSN 1381-2890.

- Lomas, Justine; Stough, Con; Hansen, Karen; Downey, Luke A. (2012-02-01). "Brief report: Emotional intelligence, victimisation and bullying in adolescents". Journal of Adolescence. 35 (1): 207–211. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.03.002. hdl:1959.3/190030. PMID 21470670.

- Rey, Lourdes; Quintana-Orts, Cirenia; Mérida-López, Sergio; Extremera, Natalio (2018-07-01). "Emotional intelligence and peer cybervictimisation in adolescents: Gender as moderator". Comunicar (in Spanish). 26 (56): 09–18. doi:10.3916/c56-2018-01. ISSN 1134-3478.

- Mayer, J.D.; Roberts, R.D; Barasade, S.G. (2008). "Human abilities: Emotional intelligence". Annual Review of Psychology. 59: 507–536. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093646. PMID 17937602.

- Tolegenova, A.A.; Jakupov, S.M.; Cheung Chung, Man; Saduova, S.; Jakupov, M.S (2012). "A theoretical formation of emotional intelligence and childhood trauma among adolescents". Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences. 69: 1891–1894. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.12.142.

- Mckenna, J.; Webb, J. (2013). "Emotional intelligence". British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 76 (12): 560. doi:10.1177/030802261307601202.

- Côté, Stéphane; Miners, Christopher T. H. (2006-01-01). "Emotional Intelligence, Cognitive Intelligence, and Job Performance". Administrative Science Quarterly. 51 (1): 1–28. doi:10.2189/asqu.51.1.1. JSTOR 20109857.

- Relojo, D.; Pilao, S.J.; Dela Rosa, R. (2015). "From passion to emotion: Emotional quotient as predictor of work attitude behavior among faculty member" (PDF). Journal of Educational Psychology. 8 (4): 1–10. doi:10.26634/jpsy.8.4.3266.

- Farh, C. C.; Seo, Tesluk (March 5, 2012). "Emotional Intelligence, Teamwork Effectiveness, and Job Performance: The Moderating Role of Job Context". Journal of Applied Psychology. 97 (4): 890–900. doi:10.1037/a0027377. PMID 22390388.

- Ahmetoglu, Gorkan; Leutner, Franziska; Chamorro-Premuzic, Tomas (December 2011). "EQ-nomics: Understanding the relationship between individual differences in trait emotional intelligence and entrepreneurship" (PDF). Personality and Individual Differences. 51 (8): 1028–1033. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.08.016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-11-01.

- Joseph, Dana L.; Jin, Jing; Newman, Daniel A.; O’Boyle, Ernest H. (2015). "Why does self-reported emotional intelligence predict job performance? A meta-analytic investigation of mixed EI". Journal of Applied Psychology. 100 (2): 298–342. doi:10.1037/a0037681. PMID 25243996.

- Van Rooy, David L; Viswesvaran, Chockalingam (2004-08-01). "Emotional intelligence: A meta-analytic investigation of predictive validity and nomological net". Journal of Vocational Behavior. 65 (1): 71–95. doi:10.1016/S0001-8791(03)00076-9.

- Sy, Thomas; Tram, Susanna; O’Hara, Linda A. (2006-06-01). "Relation of employee and manager emotional intelligence to job satisfaction and performance". Journal of Vocational Behavior. 68 (3): 461–473. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2005.10.003.

- Goleman, Daniel (1994). Emotional Intelligence. Bantam Books. ISBN 9780747526254.

- Law, Kenneth S.; Wong, Chi-Sum; Song, Lynda J. (2004). "The Construct and Criterion Validity of Emotional Intelligence and Its Potential Utility for Management Studies". Journal of Applied Psychology. 89 (3): 483–496. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.89.3.483. PMID 15161407.

- Lopes, Paulo N.; Grewal, Daisy; Kadis, Jessica; Gall, Michelle; Salovey, Peter (2006-01-01). "Evidence that emotional intelligence is related to job performance and affect and attitudes at work". Psicothema. 18 Suppl: 132–138. ISSN 0214-9915. PMID 17295970.

- Seibert, Scott E.; Kraimer, Maria L.; Liden, Robert C. (2001-01-01). "A Social Capital Theory of Career Success". The Academy of Management Journal. 44 (2): 219–237. doi:10.2307/3069452. JSTOR 3069452.

- Vratskikh, Ivan; Masa'deh, Ra'ed (Moh’dTaisir); Al-Lozi, Musa; Maqableh, Mahmoud; ANALIA, Penney (2016-01-25). "The Impact of Emotional Intelligence on Job Performance via the Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction". International Journal of Business and Management. 11 (2): 69. doi:10.5539/ijbm.v11n2p69. ISSN 1833-8119.

- "What Everyone Should Know About Managing Up". Harvard Business Review. 2015-01-23. Archived from the original on 2016-04-26. Retrieved 2016-04-19.

- Janssen, Onne; Yperen, Nico W. Van (2004-06-01). "Employees' Goal Orientations, the Quality of Leader-Member Exchange, and the Outcomes of Job Performance and Job Satisfaction". Academy of Management Journal. 47 (3): 368–384. doi:10.2307/20159587. hdl:2066/64290. ISSN 0001-4273. JSTOR 20159587. Archived from the original on 2015-03-21.

- Ashkanasy, Neal M.; Daus, Catherine S. (2005-06-01). "Rumors of the death of emotional intelligence in organizational behavior are vastly exaggerated" (PDF). Journal of Organizational Behavior. 26 (4): 441–452. doi:10.1002/job.320. ISSN 1099-1379.

- O'Boyle, Ernest H.; Humphrey, Ronald H.; Pollack, Jeffrey M.; Hawver, Thomas H.; Story, Paul A. (2011-07-01). "The relation between emotional intelligence and job performance: A meta-analysis". Journal of Organizational Behavior. 32 (5): 788–818. doi:10.1002/job.714. ISSN 1099-1379.

- Farh, Crystal I. C. Chien; Seo, Myeong-Gu; Tesluk, Paul E. (2012). "Emotional intelligence, teamwork effectiveness, and job performance: The moderating role of job context". Journal of Applied Psychology. 97 (4): 890–900. doi:10.1037/a0027377. PMID 22390388.

- Joseph, Dana L.; Newman, Daniel A. (2010). "Emotional intelligence: An integrative meta-analysis and cascading model". Journal of Applied Psychology. 95 (1): 54–78. doi:10.1037/a0017286. PMID 20085406.

- Moon, Tae Won; Hur, Won-Moo (2011-09-01). "Emotional Intelligence, Emotional Exhaustion, And Job Performance". Social Behavior and Personality. 39 (8): 1087–1096. doi:10.2224/sbp.2011.39.8.1087.

- Dabke, Deepika (2016). "Impact of Leader's Emotional Intelligence and Transformational Behavior on Perceived Leadership Effectiveness: A Multiple Source View". Business Perspectives and Research. 4 (1): 27–40. doi:10.1177/2278533715605433.

- Ahiauzu, Augustine; Nwokah, N. Gladson (2010). "Marketing in governance: emotional intelligence leadership for effective corporate governance". Corporate Governance. 10 (2): 150–162. doi:10.1108/14720701011035675.

- Mullen, Patrick; Gutierrez, Daniel; Newhart, Sean (2018). "School Counselors' Emotional Intelligence and Its Relationship to Leadership". Professional School Counseling. 32 (1b): 2156759X1877298. doi:10.1177/2156759X18772989.

- Schutte (1 April 2007). "A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between emotional intelligence and health". ResearchGate. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015.

- Alexandra Martins (1 October 2010). "A comprehensive meta-analysis of the relationship between Emotional Intelligence and health". ResearchGate. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015.

- Mayer, John D.; Salovey, Peter (1993). "The Intelligence of Emotional Intelligence" (PDF). Intelligence. 17: 433–442.

- Nehra DK, Sharma V, Mushtaq H, Sharma NR, Sharma M, Nehra S (July 2012). "Emotional intelligence and self esteem in cannabis abusers" (PDF). Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology. 38 (2): 385–393.

- Brown, Chiu; Chiu, Edmond; Neill, Lloyd; Tobin, Juliet; Reid, John (16 Jan 2012). "Is low emotional intelligence a primary causal factor in drug and alcohol addiction?". Australian Academic Press (Bowen Hills, QLD, Australia): 91–101. S2CID 73720582.

Further reading

- Goleman, Daniel (1996). Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ. Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-38371-3.

- Harvard Business Review's 10 Must Reads: On Emotional Intelligence. Boston: HBR. 2015. ISBN 978-1511367196.

- Mayer, John; Salovey, Peter (1993). "The Intelligence of Emotional Intelligence" (PDF): 433–442. Retrieved 9 May 2018. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)