Montenegro

Montenegro (/ˌmɒntɪˈneɪɡroʊ, -ˈniːɡroʊ, -ˈnɛɡroʊ/ (![]()

Montenegro | |

|---|---|

| |

| Capital and largest city | Podgorica 42°47′N 19°28′E |

| Official languages | Montenegrin (national)[1] Serbian, Bosnian, Albanian, Croatian (in official use)[2] |

| Writing system | Latin, Cyrillic |

| Ethnic groups (2011[3]) |

|

| Religion (2011) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Montenegrin |

| Government | Unitary dominant-party parliamentary constitutional republic |

| Milo Đukanović | |

| Duško Marković | |

| Ivan Brajović | |

| Legislature | Skupština |

| Establishment history | |

| 625 | |

• Duklja gains independence | 1042 |

• Kingdom of Duklja proclaimed | 1077 |

• Kingdom of Zeta proclaimed | 1373 |

• Prince-Bishopric of Montenegro founded | 1516 |

| 1 January 1852 | |

| 28 August 1910 | |

• Formation of Yugoslavia | 1 December 1918 |

• Independence regained | 3 June 2006 |

| Area | |

• Total | 13,812 km2 (5,333 sq mi) (156th) |

• Water (%) | 2.6 |

| Population | |

• 2018 estimate | |

• Density | 45/km2 (116.5/sq mi) (133rd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $13.081 billion[5] |

• Per capita | $20,977[5] (74th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $5.685 billion[5] |

• Per capita | $9,116[5] (72nd) |

| Gini (2017) | medium |

| HDI (2018) | very high · 52nd |

| Currency | Euro (€)a (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| UTC+2 (CEST) | |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +382 |

| ISO 3166 code | ME |

| Internet TLD | .me |

| |

During the Early Medieval period, three principalities were located on the territory of modern-day Montenegro: Duklja, roughly corresponding to the southern half; Travunia, the west; and Rascia proper, the north.[8][9][10] In 1042, archon Stefan Vojislav led a revolt that resulted in the independence of Duklja from the Byzantine Empire and the establishment of the Vojislavljević dynasty. After being ruled by the Nemanjić dynasty for two centuries, the independent Principality of Zeta emerged in the 14th and 15th centuries, ruled by the House of Balšić between 1356 and 1421, and by the House of Crnojević between 1431 and 1498, when the name Montenegro started being used for the country. After falling under Ottoman rule, Montenegro regained de facto independence in 1697 under the rule of the House of Petrović-Njegoš, first under the theocratic rule of prince-bishops, before being transformed into a secular principality in 1852. Montenegro's de jure independence was recognised by the Great Powers at the Congress of Berlin in 1878, following the Montenegrin–Ottoman War. In 1905, the country became a kingdom. After World War I, it became part of Yugoslavia. Following the breakup of Yugoslavia, the republics of Serbia and Montenegro together established a federation known as the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, which was renamed to the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro in 2003. On the basis of an independence referendum held in May 2006, Montenegro declared independence and the federation peacefully dissolved on 3 June of that year, ending a nearly 88-year union between the two states.[11]

Since 1990, the state of Montenegro has been governed by the Democratic Party of Socialists and its minor coalition partners. Some foreign observers consider Montenegro's government, headed by Milo Đukanović, to be autocratic and kleptocratic.[12]

Classified by the World Bank as an upper middle-income country, Montenegro is a member of the UN, NATO, the World Trade Organization, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, the Council of Europe, and the Central European Free Trade Agreement. Montenegro is a founding member of the Union for the Mediterranean. It is also in the process of joining the European Union.

Etymology

The country's English name derives from Venetian and translates as "Black Mountain", deriving from the appearance of Mount Lovćen when covered in dense evergreen forests.[13] In the monuments of Kotor, Montenegro was mentioned as Montenegro in 1397, as Monte Nigro in 1443 and as Crna Gora in 1435 and 1458, but there are much older papers of Latin sources where Montenegro is mentioned as Monte nigro. The first mention of Montenegro (as Monte nigro) dates to 9 November 1053 in a papal epistle and the others date to 1061, 1097, 1121, 1125, 1144, 1154, 1179 and 1189.[14]

The native name Crna Gora, also meaning "black mountain," came to denote the majority of contemporary Montenegro in the 15th century.[15] Originally, it had referred to only a small strip of land under the rule of the Paštrovići, but the name eventually came to be used for the wider mountainous region after the Crnojević noble family took power in Upper Zeta.[15] The aforementioned region became known as Stara Crna Gora 'Old Montenegro' by the 19th century to distinguish the independent region from the neighbouring Ottoman-occupied Montenegrin territory of Brda '(The) Highlands'. Montenegro further increased its size several times by the 20th century, as the result of wars against the Ottoman Empire, which saw the annexation of Old Herzegovina and parts of Metohija and southern Raška. Its borders have changed little since then, losing Metohija and gaining the Bay of Kotor.

The ISO Alpha-2 code for Montenegro is ME and the Alpha-3 Code is MNE.[16]

History

Arrival of the Slavs

In the 9th century, three Slavic principalities were located on the territory of Montenegro: Duklja, roughly corresponding to the southern half, Travunia, the west, and Rascia, the north.[8][9] Duklja gained its independence from the Byzantine Roman Empire in 1042. Over the next few decades, it expanded its territory to neighbouring Rascia and Bosnia, and also became recognised as a kingdom. Its power started declining at the beginning of the 12th century. After King Bodin's death (in 1101 or 1108), several civil wars ensued. Duklja reached its zenith under Vojislav's son, Mihailo (1046–81), and his grandson Constantine Bodin (1081–1101).[17]

By the 13th century, Zeta had replaced Duklja when referring to the realm. In the late 14th century, southern Montenegro (Zeta) came under the rule of the Balšić noble family, then the Crnojević noble family, and by the 15th century, Zeta was more often referred to as Crna Gora (Venetian: monte negro).

As the nobility fought for the throne, the kingdom was weakened, and by 1186, it was conquered by Stefan Nemanja and incorporated into the Serbian realm as a province named Zeta. After the Serbian Empire collapsed in the second half of the 14th century, the most powerful Zetan family, the Balšićs, became sovereigns of Zeta.

In 1421, Zeta was annexed to the Serbian Despotate, but after 1455, another noble family from Zeta, the Crnojevićs, became sovereign rulers of the country, making it the last free monarchy of the Balkans before it fell to the Ottomans in 1496, and got annexed to the sanjak of Shkodër. During the reign of Crnojevićs, Zeta became known under its current name – Montenegro. For a short time, Montenegro existed as a separate autonomous sanjak in 1514–1528 (Sanjak of Montenegro). Also, Old Herzegovina region was part of Sanjak of Herzegovina.

Ottoman period

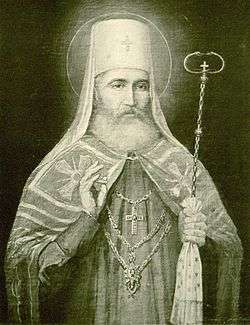

Right: Petar II Petrović-Njegoš was a Prince-Bishop (vladika) of Montenegro and the national poet and philosopher, Oil painting of Njegoš as vladika, c. 1837

Large portions fell under the control of the Ottoman Empire from 1496 to 1878. In the 16th century, Montenegro developed a unique form of autonomy within the Ottoman Empire permitting Montenegrin clans freedom from certain restrictions. Nevertheless, the Montenegrins were disgruntled with Ottoman rule, and in the 17th century, raised numerous rebellions, which culminated in the defeat of the Ottomans in the Great Turkish War at the end of that century.

Montenegro consisted of territories controlled by warlike clans. Most clans had a chieftain (knez), who was not permitted to assume the title unless he proved to be as worthy a leader as his predecessor. The great assembly of Montenegrin clans (Zbor) was held every year on 12 July in Cetinje, and any adult clansman could take part.

Parts of the territory were controlled by Republic of Venice and the First French Empire and Austria-Hungary, its successors. In 1515, Montenegro became a theocracy led by the Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Littoral, which flourished after the Petrović-Njegoš of Cetinje became the traditional prince-bishops (whose title was "Vladika of Montenegro"). However, the Venetian Republic introduced governors who meddled in Montenegrin politics. The republic was succeeded by the Austrian Empire in 1797, and the governors were abolished by Prince-Bishop Petar II in 1832.

People from Montenegro in this historical period have been described as Orthodox Serbs.[18]

Principality and Kingdom of Montenegro

Under Nicholas I (ruled 1860-1918), the principality was enlarged several times in the Montenegro-Turkish Wars and was recognised as independent in 1878. Nicholas I established diplomatic relations with the Ottoman Empire. Minor border skirmishes excepted, diplomacy ushered in about 30 years of peace between the two states until the deposition of Abdul Hamid II in 1909.[19]

The political skills of Abdul Hamid II and Nicholas I played a major role in the mutually amicable relations.[19] Modernization of the state followed, culminating with the draft of a Constitution in 1905. However, political rifts emerged between the reigning People's Party, who supported the process of democratization and union with Serbia, and those of the True People's Party, who were monarchist.

In 1858 one of the major Montenegrin victories over the Ottomans occurred at the Battle of Grahovac. Grand Duke Mirko Petrović, elder brother of Knjaz Danilo, led an army of 7,500 and defeated the numerically superior Ottomans (who had 15,000 troops) at Grahovac on 1 May 1858. This forced the Great Powers to officially demarcate the borders between Montenegro and Ottoman Empire, de facto recognizing Montenegro's independence. The Ottoman Empire recognized Montenegrin independence in the Treaty of Berlin in 1878.

The first Montenegrin constitution (also known as the Danilo Code) was proclaimed in 1855.

In 1910 Montenegro became a kingdom, and as a result of the Balkan wars in 1912 and 1913 (in which the Ottomans lost most of their Balkan lands), a common border with Serbia was established, with Shkodër being awarded to a newly-created Albania, though the current capital city of Montenegro, Podgorica, was on the old border of Albania and Yugoslavia.

Montenegro became one of the Allied Powers during World War I (1914–18). From 1916 to October 1918 Austria-Hungary occupied Montenegro. During the occupation, King Nicholas fled the country and a government-in-exile was set up in Bordeaux.

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

In 1922, Montenegro formally became the Oblast of Cetinje in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, with the addition of the coastal areas around Budva and Bay of Kotor. In a further restructuring in 1929, it became a part of a larger Zeta Banate of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia that reached the Neretva River.

Nicholas's grandson, the Serb King Alexander I, dominated the Yugoslav government. Zeta Banovina was one of nine banovinas which formed the kingdom; it consisted of the present-day Montenegro and parts of Serbia, Croatia, and Bosnia.

World War II and Socialist Yugoslavia

In April 1941, Nazi Germany, the Kingdom of Italy, and other Axis allies attacked and occupied the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Italian forces occupied Montenegro and established it as a puppet Kingdom of Montenegro.

In May, the Montenegrin branch of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia started preparations for an uprising planned for mid-July. The Communist Party and its Youth League organised 6,000 of its members into detachments prepared for guerrilla warfare. The first armed uprising in Nazi-occupied Europe happened on 13 July 1941 in Montenegro.[20]

Unexpectedly, the uprising took hold, and by 20 July, 32,000 men and women had joined the fight. Except for the coast and major towns (Podgorica, Cetinje, Pljevlja, and Nikšić), which were besieged, Montenegro was mostly liberated. In a month of fighting, the Italian army suffered 5,000 dead, wounded, and captured. The uprising lasted until mid-August, when it was suppressed by a counter-offensive of 67,000 Italian troops brought in from Albania. Faced with new and overwhelming Italian forces, many of the fighters laid down their arms and returned home. Nevertheless, intense guerrilla fighting lasted until December.

%2C_jugoslawische_Schiffe.jpg)

Fighters who remained under arms fractured into two groups. Most of them went on to join the Yugoslav Partisans, consisting of communists and those inclined towards active resistance; these included Arso Jovanović, Sava Kovačević, Svetozar Vukmanović-Tempo, Milovan Đilas, Peko Dapčević, Vlado Dapčević, Veljko Vlahović, and Blažo Jovanović. Those loyal to the Karađorđević dynasty and opposing communism went on to become Chetniks, and turned to collaboration with Italians against the Partisans.

War broke out between Partisans and Chetniks during the first half of 1942. Pressured by Italians and Chetniks, the core of the Montenegrin Partisans went to Serbia and Bosnia, where they joined with other Yugoslav Partisans. Fighting between Partisans and Chetniks continued through the war. Chetniks with Italian backing controlled most of the country from mid-1942 to April 1943. Montenegrin Chetniks received the status of "anti-communist militia" and received weapons, ammunition, food rations, and money from Italy. Most of them were moved to Mostar, where they fought in the Battle of Neretva against the Partisans, but were dealt a heavy defeat.

During the German operation Schwartz against the Partisans in May and June 1943, Germans disarmed large number of Chetniks without fighting, as they feared they would turn against them in case of an Allied invasion of the Balkans. After the capitulation of Italy in September 1943, Partisans managed to take hold of most of Montenegro for a brief time, but Montenegro was soon occupied by German forces, and fierce fighting continued during late 1943 and entire 1944. Montenegro was liberated by the Partisans in December 1944.

Montenegro became one of the six constituent republics of the communist Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY). Its capital became Podgorica, renamed Titograd in honour of President Josip Broz Tito. After the war, the infrastructure of Yugoslavia was rebuilt, industrialization began, and the University of Montenegro was established. Greater autonomy was established until the Socialist Republic of Montenegro ratified a new constitution in 1974.

Montenegro within FR Yugoslavia

After the dissolution of the SFRY in 1992, Montenegro remained part of a smaller Federal Republic of Yugoslavia along with Serbia.

In the referendum on remaining in Yugoslavia in 1992, the turnout was 66%, with 96% of the votes cast in favour of the federation with Serbia. The referendum was boycotted by the Muslim, Albanian, and Catholic minorities, as well as the pro-independence Montenegrins. The opponents claimed that the poll was organized under anti-democratic conditions with widespread propaganda from the state-controlled media in favour of a pro-federation vote. No impartial report on the fairness of the referendum was made, as it was unmonitored, unlike in a later 2006 referendum when European Union observers were present.

During the 1991–1995 Bosnian War and Croatian War, Montenegrin police and military forces joined Serbian troops in the attacks on Dubrovnik, Croatia.[21] These operations, aimed at acquiring more territory, were characterized by a consistent pattern of large-scale violations of human rights.[22]

Montenegrin General Pavle Strugar was convicted for his part in the bombing of Dubrovnik.[23] Bosnian refugees were arrested by Montenegrin police and transported to Serb camps in Foča, where they were subjected to systematic torture and executed.[24][25]

In 1996, Milo Đukanović's government severed ties between Montenegro and its partner Serbia, which was led by Slobodan Milošević. Montenegro formed its own economic policy and adopted the German Deutsche Mark as its currency and subsequently adopted the euro, although not part of the Eurozone currency union. Subsequent governments pursued pro-independence policies, and political tensions with Serbia simmered despite the political changes in Belgrade. Targets in Montenegro were bombed by NATO forces during Operation Allied Force in 1999, although the extent of these attacks was very limited in both time and area affected.[26]

In 2002, Serbia and Montenegro came to a new agreement for continued cooperation and entered into negotiations regarding the future status of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. This resulted in the Belgrade Agreement, which saw the country's transformation into a more decentralised state union named Serbia and Montenegro in 2003. The Belgrade Agreement also contained a provision delaying any future referendum on the independence of Montenegro for at least three years.

Independence and recent history

.jpg)

The status of the union between Montenegro and Serbia was decided by a referendum on Montenegrin independence on 21 May 2006. A total of 419,240 votes were cast, representing 86.5% of the total electorate; 230,661 votes (55.5%) were for independence and 185,002 votes (44.5%) were against.[27] This narrowly surpassed the 55% threshold needed to validate the referendum under the rules set by the European Union. According to the electoral commission, the 55% threshold was passed by only 2,300 votes. Serbia, the member-states of the European Union, and the permanent members of the United Nations Security Council all recognised Montenegro's independence.

The 2006 referendum was monitored by five international observer missions, headed by an Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE)/ODIHR team, and around 3,000 observers in total (including domestic observers from CDT (OSCE PA), the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE), the Congress of Local and Regional Authorities of the Council of Europe (CLRAE), and the European Parliament (EP) to form an International Referendum Observation Mission (IROM). The IROM—in its preliminary report—"assessed compliance of the referendum process with OSCE commitments, Council of Europe commitments, other international standards for democratic electoral processes, and domestic legislation." Furthermore, the report stated that the competitive pre-referendum environment was marked by an active and generally peaceful campaign and that "there were no reports of restrictions on fundamental civil and political rights."

On 3 June 2006, the Montenegrin Parliament declared the independence of Montenegro,[28] formally confirming the result of the referendum.

The Law on the Status of the Descendants of the Petrović Njegoš Dynasty was passed by the Parliament of Montenegro on 12 July 2011. It rehabilitated the Royal House of Montenegro and recognized limited symbolic roles within the constitutional framework of the republic.

In 2015, the investigative journalists' network OCCRP named Montenegro's long-time President and Prime Minister Milo Đukanović "Person of the Year in Organized Crime".[29] The extent of Đukanović's corruption led to street demonstrations and calls for his removal.[30][31]

In October 2016, for the day of the parliamentary election, a coup d'état was prepared by a group of persons that included leaders of the Montenegrin opposition, Serbian nationals and Russian agents; the coup was prevented.[32] In 2017, fourteen people, including two Russian nationals and two Montenegrin opposition leaders, Andrija Mandić and Milan Knežević, were indicted for their alleged roles in the coup attempt on charges such as "preparing a conspiracy against the constitutional order and the security of Montenegro" and an "attempted terrorist act."[33]

Montenegro formally became a member of NATO in June 2017, though "Montenegro remains deeply divided over joining NATO",[34] an event that triggered a promise of retaliatory actions on the part of Russia's government.[35][36][37]

Montenegro has been in negotiations with the EU since 2012. In 2018, the earlier goal of acceding by 2022[38] was revised to 2025.[39]

2019 Montenegrin protests began in February 2019 against the incumbent President Milo Đukanović and the Prime Minister Duško Marković-led government of the ruling Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS), which has been in power since 1991.[40][41]

As of late December 2019, the newly adopted Law on Religion, which de jure transfers the ownership of church buildings and estates built before 1918 from the Serbian Orthodox Church to the Montenegrin state,[42][43] sparked a series of large[44] protests followed with road blockages.[45] Seventeen opposition Democratic Front MPs were arrested prior to the voting for violently disrupting the vote.[46] Demonstrations continued into March[47] 2020 as peaceful protest walks, mostly organised by the Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Littoral in a number of Montenegrin municipalities.[48][49][50]

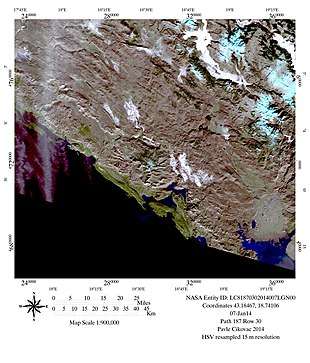

Geography

Montenegro ranges from high peaks along its borders with Serbia, Kosovo, and Albania, a segment of the Karst of the western Balkan Peninsula, to a narrow coastal plain that is only 1.5 to 6 kilometres (1 to 4 miles) wide. The plain stops abruptly in the north, where Mount Lovćen and Mount Orjen plunge into the inlet of the Bay of Kotor.

Montenegro's large karst region lies generally at elevations of 1,000 metres (3,280 ft) above sea level; some parts, however, rise to 2,000 m (6,560 ft), such as Mount Orjen (1,894 m or 6,214 ft), the highest massif among the coastal limestone ranges. The Zeta River valley, at an elevation of 500 m (1,600 ft), is the lowest segment.

The mountains of Montenegro include some of the most rugged terrain in Europe, averaging more than 2,000 metres (6,600 feet) in elevation. One of the country's notable peaks is Bobotov Kuk in the Durmitor mountains, which reaches a height of 2,522 m (8,274 ft). Owing to the hyperhumid climate on their western sides, the Montenegrin mountain ranges were among the most ice-eroded parts of the Balkan Peninsula during the last glacial period.

_07.jpg)

.jpg)

Internationally, Montenegro borders Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Kosovo,[lower-alpha 1] and Albania. It lies between latitudes 41° and 44°N, and longitudes 18° and 21°E.

- Longest beach: Velika Plaža, Ulcinj – 13,000 m (8.1 mi)

- Highest peak: Zla Kolata, Prokletije at 2,535 m (8,317 ft)

- Largest lake: Skadar Lake – 391 km2 (151 sq mi) of surface area

- Deepest canyon: Tara River Canyon – 1,300 m (4,300 ft)

- Biggest bay: Bay of Kotor

- Deepest cave: Iron Deep 1,169 m (3,835 ft), exploring started in 2012, now more than 3,000 m (9,800 ft) long[51]

| Name | Established | Area |

|---|---|---|

| Durmitor National Park | 1952 | 390 square kilometres (39,000 ha) |

| Biogradska Gora | 1952 | 54 square kilometres (5,400 ha) |

| Lovćen National Park | 1952 | 64 square kilometres (6,400 ha) |

| Lake Skadar National Park | 1983 | 400 square kilometres (40,000 ha) |

| Prokletije National Park | 2009 | 166 square kilometres (16,600 ha) |

Montenegro is a member of the International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River, as more than 2,000 km2 (772 sq mi) of the country's territory lie within the Danube catchment area.

Biodiversity

The diversity of the geological base, landscape, climate, and soil, and the position of Montenegro on the Balkan Peninsula and Adriatic Sea, created the conditions for high biological diversity, putting Montenegro among the "hot-spots" of European and world biodiversity. The number of species per area unit index in Montenegro is 0.837, which is the highest index recorded in any European country.[52]

Politics

.jpg) |  |

| Milo Đukanović President |

Duško Marković Prime Minister |

The Constitution of Montenegro describes the state as a "civic, democratic, ecological state of social justice, based on the reign of Law."[53] Montenegro is an independent and sovereign republic that proclaimed its new constitution on 22 October 2007.

The President of Montenegro (Montenegrin: Predsjednik Crne Gore) is the head of state, elected for a period of five years through direct elections. The President represents the country abroad, promulgates laws by ordinance, calls elections for the Parliament, and proposes candidates for Prime Minister, president and justices of the Constitutional Court to the Parliament. The President also proposes the calling of a referendum to Parliament, grants amnesty for criminal offences prescribed by the national law, confers decoration and awards and performs other constitutional duties and is a member of the Supreme Defence Council. The official residence of the President is in Cetinje.

The Government of Montenegro (Montenegrin: Vlada Crne Gore) is the executive branch of government authority of Montenegro. The government is headed by the Prime Minister, and consists of the deputy prime ministers as well as ministers.[54]

The Parliament of Montenegro (Montenegrin: Skupština Crne Gore) is a unicameral legislative body. It passes laws, ratifies treaties, appoints the Prime Minister, ministers, and justices of all courts, adopts the budget and performs other duties as established by the Constitution. Parliament can pass a vote of no-confidence in the Government by a simple majority. One representative is elected per 6,000 voters. The present parliament contains 81 seats, with 39 seats held by the Coalition for a European Montenegro after the 2012 parliamentary election.

In 2020, the Freedom House reported that years of increasing state capture, abuse of power, and strongman tactics employed by the President Đukanović have tipped his country over the edge — for the first time since 2003, Montenegro is no longer categorized as democracy and became hybrid regime.[55]

Foreign relations of Montenegro

.jpg)

After the promulgation of the Declaration of Independence in the Parliament of the Republic of Montenegro on 3 June 2006, following the independence referendum held on 21 May, the Government of the Republic of Montenegro assumed the competences of defining and conducting the foreign policy of Montenegro as a subject of international law and a sovereign state. The implementation of this constitutional responsibility was vested in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which was given the task of defining the foreign policy priorities and activities needed for their implementation. These activities are pursued in close cooperation with other state administration authorities, the President, the Speaker of the Parliament, and other relevant stakeholders.[56]

Integration into the European Union is Montenegro's strategic goal. This process will remain in the focus of Montenegrin foreign policy in the short term. The second strategic and equally important goal, but one attainable in a shorter time span, was joining NATO, which would guarantee stability and security for pursuing other strategic goals. Montenegro believes NATO integration would speed up EU integration.[56] In May 2017 NATO accepted Montenegro as a NATO member starting 5 June 2017.[57]

Symbols

An official flag of Montenegro, based on the royal standard of King Nicholas I, was adopted on 12 July 2004 by the Montenegrin legislature. This royal flag was red with a silver border, a silver coat of arms, and the initials НІ, in Cyrillic script (corresponding to NI in Latin script), representing King Nicholas I. On the current flag, the border and arms are in gold and the royal cipher in the centre of the arms has been replaced with a golden lion.

The national day of 13 July marks the date in 1878 when the Congress of Berlin recognized Montenegro as the 27th independent state in the world[58] and the start of one of the first popular uprisings in Europe against the Axis Powers on 13 July 1941 in Montenegro.

In 2004, the Montenegrin legislature selected a popular Montenegrin traditional song, "Oh, Bright Dawn of May", as the national anthem. Montenegro's official anthem during the reign of King Nicholas I was Ubavoj nam Crnoj Gori ("To Our Beautiful Montenegro").

Military

The military of Montenegro is a fully professional standing army under the Ministry of Defence and is composed of the Montenegrin Ground Army, the Montenegrin Navy, and the Montenegrin Air Force, along with special forces. Conscription was abolished in 2006. The military currently maintains a force of 1,920 active duty members. The bulk of its equipment and forces were inherited from the armed forces of the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro; as Montenegro contained the entire coastline of the former union, it retained practically the entire naval force.

Montenegro was a member of NATO's Partnership for Peace program and then became an official candidate for full membership in the alliance. Montenegro applied for a Membership Action Plan on 5 November 2008, which was granted in December 2009. Montenegro is also a member of Adriatic Charter.[59] Montenegro was invited to join NATO on 2 December 2015 and on 19 May 2016, NATO and Montenegro conducted a signing ceremony at NATO headquarters in Brussels for Montenegro's membership invitation.[60] Montenegro became NATO's 29th member on 5 June 2017, despite Russia's objections.[61] The government plans to have the army participate in peacekeeping missions through the UN and NATO such as the International Security Assistance Force.[62]

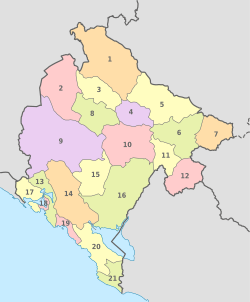

Administrative divisions

Montenegro is divided into twenty-three municipalities (opština). This includes 21 District-level Municipalities and 2 Urban Municipalities, with two subdivisions of Podgorica municipality, listed below. Each municipality can contain multiple cities and towns. Historically, the territory of the country was divided into "nahije".

Municipalities of Montenegro.  Regions of Montenegro—designed purely for the statistical purposes by the Statistical Office—have no administrative use. Note that other organization (i.e. Football Association of Montenegro) use different municipalities as a part of similar "regions". | ||

| No. | Municipality | Seat |

|---|---|---|

| Pljevlja Municipality | Pljevlja | |

| Plužine Municipality | Plužine | |

| Žabljak Municipality | Žabljak | |

| Mojkovac Municipality | Mojkovac | |

| Bijelo Polje Municipality | Bijelo Polje | |

| Berane / Petnjica | Berane / Petnjica (22) | |

| Rožaje Municipality | Rožaje | |

| Šavnik Municipality | Šavnik | |

| Nikšić Municipality | Nikšić | |

| Kolašin Municipality | Kolašin | |

| Andrijevica Municipality | Andrijevica | |

| Plav / Gusinje | Plav / Gusinje (23) | |

| Kotor Municipality | Kotor | |

| Old Royal Capital Cetinje | Cetinje | |

| Danilovgrad Municipality | Danilovgrad | |

| Podgorica Capital City | Podgorica / Tuzi (24) | |

| Herceg Novi Municipality | Herceg Novi | |

| Tivat Municipality | Tivat | |

| Budva Municipality | Budva | |

| Bar Municipality | Bar | |

| Ulcinj Municipality | Ulcinj |

Cities in Montenegro

Economy

The economy of Montenegro is mostly service-based and is in late transition to a market economy. According to the International Monetary Fund, the nominal GDP of Montenegro was $5.424 billion in 2019.[5] The GDP PPP for 2019 was $12.516 billion, or $20,083 per capita.[5] According to Eurostat data, the Montenegrin GDP per capita stood at 48% of the EU average in 2018.[64] The Central Bank of Montenegro is not part of the euro system but the country is "euroised", using the euro unilaterally as its currency.

GDP grew at 10.7% in 2007 and 7.5% in 2008.[65] The country entered a recession in 2008 as a part of the global recession, with GDP contracting by 4%. However, Montenegro remained a target for foreign investment, the only country in the Balkans to increase its amount of direct foreign investment.[66] The country exited the recession in mid-2010, with GDP growth at around 0.5%.[67] However, the significant dependence of the Montenegrin economy on foreign direct investment leaves it susceptible to external shocks and a high export/import trade deficit.

In 2007, the service sector made up 72.4% of GDP, with industry and agriculture making up the rest at 17.6% and 10%, respectively.[68] There are 50,000 farming households in Montenegro that rely on agriculture to fill the family budget.[69]

Infrastructure

The Montenegrin road infrastructure is not yet at Western European standards. Despite an extensive road network, no roads are built to full motorway standards. Construction of new motorways is considered a national priority, as they are important for uniform regional economic development and the development of Montenegro as an attractive tourist destination.

Current European routes that pass through Montenegro are E65 and E80.

The backbone of the Montenegrin rail network is the Belgrade–Bar railway, which provides international connection towards Serbia. There is a domestic branch line, the Nikšić-Podgorica railway, which was operated as a freight-only line for decades, and is now also open for passenger traffic after the reconstruction and electrification works in 2012. The other branch line from Podgorica towards the Albanian border, the Podgorica–Shkodër railway, is not in use.

Montenegro has two international airports, Podgorica Airport and Tivat Airport. The two airports served 1.1 million passengers in 2008. Montenegro Airlines is the flag carrier of Montenegro.

The Port of Bar is Montenegro's main seaport. Initially built in 1906, the port was almost completely destroyed during World War II, with reconstruction beginning in 1950. Today, it is equipped to handle over 5 million tons of cargo annually, though the breakup of the former Yugoslavia and the size of the Montenegrin industrial sector has resulted in the port operating at a loss and well below capacity for several years. The reconstruction of the Belgrade-Bar railway and the proposed Belgrade-Bar motorway are expected to bring the port back up to capacity.

Tourism

Montenegro has both a picturesque coast and a mountainous northern region. The country was a well-known tourist spot in the 1980s. Yet, the Yugoslav wars that were fought in neighbouring countries during the 1990s crippled the tourist industry and damaged the image of Montenegro for years.

With a total of 1.6 million visitors, Montenegro is the 36th most visited country (out of 47 countries) in Europe.[70] The Montenegrin Adriatic coast is 295 km (183 mi) long, with 72 km (45 mi) of beaches and many well-preserved ancient old towns. National Geographic Traveler (edited once a decade) ranks Montenegro among the "50 Places of a Lifetime", and the Montenegrin seaside Sveti Stefan was used as the cover for the magazine.[71] The coast region of Montenegro is considered one of the great new "discoveries" among world tourists. In January 2010, The New York Times ranked the Ulcinj South Coast region of Montenegro, including Velika Plaza, Ada Bojana, and the Hotel Mediteran of Ulcinj, among the "Top 31 Places to Go in 2010" as part of a worldwide ranking of tourism destinations.[72]

Montenegro was also listed by Yahoo Travel among the "10 Top Hot Spots of 2009" to visit, describing it as being "[c]urrently ranked as the second fastest growing tourism market in the world (falling just behind China)".[73] It is listed every year by prestigious tourism guides like Lonely Planet as a top tourist destination along with Greece, Spain and other popular locations.[74][75]

It was not until the 2000s that the tourism industry began to recover, and the country has since experienced a high rate of growth in the number of visits and overnight stays. The Government of Montenegro has declared the development of Montenegro as an elite tourist destination a top priority. It is a national strategy to make tourism a major contributor to the Montenegrin economy. A number of steps were taken to attract foreign investors. Some large projects are already under way, such as Porto Montenegro, while other locations, like Jaz Beach, Buljarica, Velika Plaža and Ada Bojana, have perhaps the greatest potential to attract future investments and become premium tourist spots on the Adriatic.

Demographics

Ethnic structure

According to the 2003 census, Montenegro has 620,145 citizens. If the methodology used up to 1991 had been adopted in the 2003 census, Montenegro would officially have recorded 673,094 citizens. The results of the 2011 census show that Montenegro has 620,029 citizens.[76]

Montenegro is a multiethnic state in which no ethnic group forms a majority.[77][78] Major ethnic groups include Montenegrins (Црногорци/Crnogorci) and Serbs (Срби/Srbi); others are Bosniaks (Bošnjaci), Albanians (Albanci – Shqiptarët) and Croats (Hrvati). The number of "Montenegrins" and "Serbs" fluctuates widely from census to census due to changes in how people perceive, experience, or choose to express, their identity and ethnic affiliation.[79][80][81]

Ethnic composition according to the 2011 official data:[76]

| Number | % | |

| Total | 620,029 | 100 |

| Montenegrins | 278,865 | 45.0 |

| Serbs | 178,110 | 28.7 |

| Bosniaks | 53,605 | 8.6 |

| Albanians | 30,439 | 4.9 |

| Muslims by nationality | 20,537 | 3.3 |

| Croats | 6,021 | 1.0 |

| Roma | 5,251 | 0.8 |

| Serbo-Montenegrins | 2,103 | 0.3 |

| "Egyptians" | 2,054 | 0.3 |

| Montenegrins-Serbs | 1,833 | 0.3 |

| Yugoslavs | 1,154 | 0.2 |

| Russians | 946 | 0.2 |

| Macedonians | 900 | 0.2 |

| Bosnians | 427 | 0.1 |

| Slovenes | 354 | 0.1 |

| Hungarians | 337 | 0.1 |

| Muslim-Montenegrins | 257 | <0.1 |

| Gorani people | 197 | <0.1 |

| Muslim-Bosniaks | 183 | <0.1 |

| Bosniaks-Muslims | 181 | <0.1 |

| Montenegrin-Muslims | 175 | <0.1 |

| Italians | 135 | <0.1 |

| Germans | 131 | <0.1 |

| Turks | 104 | <0.1 |

| regional qualification | 1,202 | 0.2 |

| without declaration | 30,170 | 4.9 |

| other | 3,358 | 0.5 |

Languages

The official language in Montenegro is Montenegrin. Also, Serbian, Bosnian, Albanian and Croatian are recognized in usage. Montenegrin, Serbian, Bosnian, and Croatian are mutually intelligible, all being standard varieties of Serbo-Croatian language. Montenegrin is the plurality mother-tongue of the population under 18 years of age.[82] In 2013, Matica crnogorska announced the results of public opinion research regarding the identity attitudes of the citizens of Montenegro, indicating that the majority of the population claims Montenegrin as their mother tongue.[83] Previous constitutions endorsed Serbo-Croatian as the official language in SR Montenegro and Serbian of Ijekavian standard during the 1992–2006 period.

According to the 2011 Census the following languages are spoken in the country:[76]

| Number | % | |

| Total | 620,029 | 100 |

| Serbian | 265,895 | 42.9 |

| Montenegrin | 229,251 | 37.0 |

| Bosnian | 33,077 | 5.3 |

| Albanian | 32,671 | 5.3 |

| Serbo-Croatian | 12,559 | 2.0 |

| Roma | 5,169 | 0.8 |

| Bosniak | 3,662 | 0.6 |

| Croatian | 2,791 | 0.5 |

| Russian | 1,026 | 0.2 |

| Serbo-Montenegrin | 618 | 0.1 |

| Macedonian | 529 | 0.1 |

| Montenegrin-Serbian | 369 | 0.1 |

| Hungarian | 225 | <0.1 |

| Croatian-Serbian | 224 | <0.1 |

| English | 185 | <0.1 |

| German | 129 | <0.1 |

| Slovene | 107 | <0.1 |

| Romanian | 101 | <0.1 |

| mother tongue | 3,318 | 0.5 |

| regional languages | 458 | 0.1 |

| without declaration | 24,748 | 4.0 |

| other | 2,917 | 0.5 |

Religion

Montenegro has been historically at the crossroads of multiculturalism and over centuries this has shaped its unique form of co-existence between Muslim and Christian populations.[85] Montenegrins have been, historically, members of the Serbian Orthodox Church (governed by the Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Littoral), and Serbian Orthodox Christianity is the most popular religion today in Montenegro. The Montenegrin Orthodox Church was recently founded and is followed by a small minority of Montenegrins although it is not in communion with any other Christian Orthodox Church as it has not been officially recognized.

.

Despite tensions between religious groups during the Bosnian War, Montenegro remained fairly stable, mainly due its population having a historic perspective on religious tolerance and faith diversity.[86] Religious institutions from Montenegro all have guaranteed rights and are separate from the state. The second largest religion is Islam, which amounts to 19% of the total population of the country. One third of Albanians are Catholics (8,126 in the 2004 census) while the two other thirds (22,267) are mainly Sunni Muslims; in 2012 a protocol passed that recognizes Islam as an official religion in Montenegro, ensures that halal foods will be served at military facilities, hospitals, dormitories and all social facilities; and that Muslim women will be permitted to wear headscarves in schools and at public institutions, as well as ensuring that Muslims have the right to take Fridays off work for the Jumu'ah (Friday)-prayer.[87]Since the time of Vojislavljević dynasty Catholicism is autochthonous in Montenegrin area.[88] There is also a small Roman Catholic population, mostly Albanians with some Croats, divided between the Archdiocese of Antivari headed by the Primate of Serbia and the Diocese of Kotor that is a part of the Catholic Church in Croatia.

.

Religious determination according to the 2011 census:[76]

| Religion | Number | % |

| Total | 620,029 | 100 |

| Eastern Orthodox | 446,858 | 72.1 |

| Catholics | 21,299 | 3.4 |

| Protestants | 143 | <0.1 |

| Adventists | 894 | 0.1 |

| Jehovah's Witnesses | 145 | <0.1 |

| Other Christians | 1,460 | 0.2 |

| Islam/Muslims | 118,477 |

19.1 |

| Buddhists | 118 | <0.1 |

| Atheists | 7,667 | 1.2 |

| Agnostics | 451 | 0.1 |

| other | 6,337 | 1.0 |

| without declaration | 16,180 | 2.6 |

Education

Education in Montenegro is regulated by the Montenegrin Ministry of Education and Science.

Education starts in either pre-schools or elementary schools. Children enroll in elementary schools (Montenegrin: Osnovna škola) at the age of 6; it lasts 9 years. The students may continue their secondary education (Montenegrin: Srednja škola), which lasts 4 years (3 years for trade schools) and ends with graduation (Matura). Higher education lasts with a certain first degree after 3 to 6 years. There is one public university (University of Montenegro) and two private ones (Mediterranean University and University of Donja Gorica).

Elementary and secondary education

Elementary education in Montenegro is free and compulsory for all the children between the ages of 7 and 15 when children attend the "eight-year school".

Various types of elementary education are available to all who qualify, but the vocational and technical schools (gymnasiums), where the students follow four-year course which will take them up to the university entrance, are the most popular. At the secondary level there are a number of art schools, apprentice schools and teacher training schools. Those who have attended the technical schools may pursue their education further at one of two-year post-secondary schools, created in response to the needs of industry and the social services.

Secondary schools are divided in three types, and children attend one depending on choice and primary school grades:

- Gymnasium (Gimnazija / Гимназиjа) lasts for four years and offers a general, broad education. It is a preparatory school for university, and hence the most academic and prestigious.

- Professional schools (Stručna škola / Стручна школа) last for three or four years and specialize students in certain fields which may result in their attending college; professional schools offer a relatively broad education.

- Vocational schools (Zanatska škola / Занатска школа) last for three years and focus on vocational education (e.g., joinery, plumbing, mechanics) without an option of continuing education after three years.

Tertiary education

Tertiary level institutions are divided into "Higher education" (Više obrazovanje) and "High education" (Visoko obrazovanje) level faculties.

- Colleges (Fakultet) and art academies (akademija umjetnosti) last between 4 and 6 years (one year is two semesters long) and award diplomas equivalent to a Bachelor of Arts or a Bachelor of Science degree.

Higher schools (Viša škola) lasts between two and four years.

Post-graduate education

Post-graduate education (post-diplomske studije) is offered after tertiary level and offers Masters' degrees, PhD and specialization education.

Culture

Art

The culture of Montenegro has been shaped by a variety of influences throughout history. The influence of Orthodox, Ottoman (Turk), Slavic, Central European, and seafaring Adriatic cultures (notably parts of Italy, like the Republic of Venice) have been the most important in recent centuries.

Montenegro has many significant cultural and historical sites, including heritage sites from the pre-Romanesque, Gothic and Baroque periods. The Montenegrin coastal region is especially well known for its religious monuments, including the Cathedral of Saint Tryphon in Kotor[89] (Cattaro under the Venetians), the basilica of St. Luke (over 800 years), Our Lady of the Rocks (Škrpjela), the Savina Monastery and others. Medieval monasteries contain a number of artistically important frescoes.

A dimension of Montenegrin culture is the ethical ideal of Čojstvo i Junaštvo, "Humaneness and Gallantry".[90][91] The traditional folk dance of the Montenegrins is the Oro, the "eagle dance" that involves dancing in circles with couples alternating in the centre, and is finished by forming a human pyramid by dancers standing on each other's shoulders.

_11.jpg)

Literature

Montenegro's capital, Podgorica, and the former royal capital of Cetinje are the two most important centres of culture and the arts in the country.

The American author Rex Stout wrote a long series of detective novels featuring his fictional creation Nero Wolfe, who was born in Montenegro. His Nero Wolfe novel The Black Mountain was largely set in Montenegro during the 1950s.

Media

The media of Montenegro refers to mass media outlets based in Montenegro. Television, magazines, and newspapers are all operated by both state-owned and for-profit corporations which depend on advertising, subscription, and other sales-related revenues. The Constitution of Montenegro guarantees freedom of speech. As a country in transition, Montenegro's media system is under transformation.

Cuisine

Montenegrin cuisine is a result of Montenegro's long history. It is a variation of Mediterranean and Oriental. The most influence is from Italy, Turkey, Byzantine Empire/Greece, and Hungary. Montenegrin cuisine also varies geographically; the cuisine in the coastal area differs from the one in the northern highland region. The coastal area is traditionally a representative of Mediterranean cuisine, with seafood being a common dish, while the northern represents more the Oriental.

Sport

.jpg)

The Sports in Montenegro revolves mostly around team sports, such as football, basketball, water polo, volleyball, and handball. Other sports involved are boxing, tennis, swimming, judo, karate, athletics, table tennis, and chess.

The most popular sport is football. Notable players from Montenegro are Dejan Savićević, Predrag Mijatović, Mirko Vučinić, Stefan Savić and Stevan Jovetić. Montenegrin national football team, founded at 2006, played in playoffs for UEFA Euro 2012, which is the biggest success in the history of national team.

Water polo is often considered the national sport. Montenegro's national team is one of the top ranked teams in the world, winning the gold medal at the 2008 Men's European Water Polo Championship in Málaga, Spain, and winning the gold medal at the 2009 FINA Men's Water Polo World League, which was held in the Montenegrin capital, Podgorica. The Montenegrin team PVK Primorac from Kotor became a champion of Europe at the LEN Euroleague 2009 in Rijeka, Croatia.

The Montenegro national basketball team is also known for good performances and had won a lot of medals in the past as part of the Yugoslavia national basketball team. In 2006, the Basketball Federation of Montenegro along with this team joined the International Basketball Federation (FIBA) on its own, following the Independence of Montenegro. Montenegro participated on two Eurobaskets until now.

Among women sports, the national handball team is the most successful, having won the 2012 European Championship and finishing as runners-up at the 2012 Summer Olympics. ŽRK Budućnost Podgorica won two times EHF Champions League.

Chess is another popular sport and some famous global chess players, like Slavko Dedić, were born in Montenegro.

At the 2012 Olympic Games in London, Montenegro women's national handball team won the country's first Olympic medal by winning silver. They lost in the final to defending World, Olympic and European Champions, Norway 26–23. Following this defeat the team won against Norway in the final of the 2012 European Championship, becoming champions for the first time.

Public holidays

| Date | Name | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 January | New Year's Day | (non-working holiday) |

| 7 January | Orthodox Christmas | (non-working) |

| 10 April * | Orthodox Good Friday | (non-working) |

| 12 April * | Orthodox Easter | (non-working) |

| 1 May | Labour Day | (non-working) |

| 9 May | Victory Day | |

| 21 May | Independence Day | (non-working) |

| 13 July | Statehood Day | (non-working) |

*2020 dates – exact dates vary each year according to the Orthodox calendar

References

Notes

- Kosovo is the subject of a territorial dispute between the Republic of Kosovo and the Republic of Serbia. The Republic of Kosovo unilaterally declared independence on 17 February 2008, but Serbia continues to claim it as part of its own sovereign territory. The two governments began to normalise relations in 2013, as part of the 2013 Brussels Agreement. Kosovo is currently recognized as an independent state by 97 out of the 193 United Nations member states. In total, 112 UN member states recognized Kosovo at some point, of which 15 later withdrew their recognition.

Citations

- "Language and alphabet Article 13". Constitution of Montenegro. WIPO. 19 October 2007.

The official language in Montenegro shall be Montenegrin. Latin and Cyrillic alphabet shall be equal.

- "Language and alphabet Article 13". Constitution of Montenegro. WIPO. 19 October 2007.

Serbian, Bosnian, Albanian and Croatian shall also be in the official use.

- "Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Montenegro 2011" (PDF). Monstat. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- http://www.monstat.org/eng/page.php?id=234&pageid=48

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. October 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income - EU-SILC survey". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- "Human Development Report 2019" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 10 December 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- David Luscombe; Jonathan Riley-Smith (2004). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 4, c. 1024 – c. 1198. Cambridge University Press. pp. 266–. ISBN 9780521414111.

- Jean W Sedlar (2013). East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000–1500. University of Washington Press. pp. 21–. ISBN 9780295800646.

- John Van Antwerp Fine (1983). he early medieval Balkans: a critical survey from the sixth to the late twelfth century. University of Michigan Press. p. 194. ISBN 9780472100255.

- Serbia ends union with Montenegro

-

- "Montenegro's Prime Minister Resigns, Perhaps Bolstering Country's E.U. Hopes". The New York Times. 26 October 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- "Montenegro's Djukanovic Declares Victory In Presidential Election". Radio Free Europe. 16 April 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- "Djukanovic si riprende il Montenegro con la benedizione di Bruxelles". eastwest.eu. 17 April 2018. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- "Đukanović - posljednji autokrat Balkana". Deutsche Welle. 18 June 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- "Montenegro veteran PM Djukanovic to run for presidency". France 24. 19 March 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- Tol, Tol (2016). "Conflict & Diplomacy: Montenegro: Ignored for 30 Years, Now At The Forefront Of The New Cold war". Transitions Online. 12 (4): 13–16.

- "Content of the Form": NATO and the democratizing of Montenegro". openDemocracy. 16 February 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- "PM+: Montenegro's 'Façade democracy' conceals corrupt and authoritarian regime". The Parliament Magazine. 12 November 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- "Montenegro History – Part I". visit-montenegro.com. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- "PRVI POMENI CRNE GORE - Marijan Mašo Miljić" (PDF). www.maticacrnogorska.me.

- Fine 1994, p. 532

- "ISO 3166-1 Newsletter No. V-12, Date: 26 September 2006". Archived from the original on 20 August 2008.

- "Duklja, the first Montenegrin state". Montenegro.org. Archived from the original on 16 January 1997. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- Crampton, R. J.; Crampton, R. J.; UK), R. J. (St Edmund's College Crampton, University of Oxford (1997). Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century-- and After. Psychology Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-415-16422-1.

- Uğur Özcan, II. Abdülhamid Dönemi Osmanlı-Karadağ Siyasi İlişkileri (Political relations between the Ottoman Empire and Montenegro in the Abdul Hamid II era) Türk Tarih Kurumu, Ankara 2013. ISBN 9789751625274

- "Prema oceni istoričara, Trinaestojulski ustanak bio je prvi i najmasovniji oružani otpor u porobljenoj Evropi 1941. godine" (in Serbian). B92.net. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- "Bombing of Dubrovnik". Croatiatraveller.com. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- "A/RES/47/121. The situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina". United Nations. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- "YIHR.org" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 April 2015.

- Annex VIII – part 3/10 Prison Camps. ess.uwe.ac.uk Archived 20 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "Porodica Nedžiba Loje o Njegovom Hapšenju i Deportaciji 1992". Godine Bosnjaci.net Archived 12 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Russia pushes peace plan". BBC. 29 April 1999.

- "Montenegro vote result confirmed". BBC News. 23 May 2006. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- "Montenegro declares independence". BBC News. 4 June 2006. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- "OCCRP announces 2015 Organized Crime and Corruption ‘Person of the Year’ Award". Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project.

- "The Balkans’ Corrupt Leaders are Playing NATO for a Fool". Foreign Policy. 5 January 2017.

- "Montenegro invited to join NATO, a move sure to anger Russia, strain alliance's standards". The Washington Times. 1 December 2015.

- Stojanovic, Dusan (31 October 2016). "NATO, Russia to Hold Parallel Drills in the Balkans". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 7 November 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

"Russians behind Montenegro coup attempt, says prosecutor". Germany: Deutsche Welle. AFP, Reuters, AP. 6 November 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

"Montenegro Prosecutor: Russian Nationalists Behind Alleged Coup Attempt". The Wall Street Journal. United States. 6 November 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

"'Russian nationalists' behind Montenegro PM assassination plot". United Kingdom: BBC. 6 November 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016. - Montenegrin Court Confirms Charges Against Alleged Coup Plotters Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty/Radio Liberty, 8 June 2017.

- Indictment tells murky Montenegrin coup tale: Trial will hear claims of Russian involvement in plans to assassinate prime minister and stop Balkan country's NATO membership. Politico, 23 May 2017.

- Montenegro finds itself at heart of tensions with Russia as it joins Nato: Alliance that bombed country only 18 years ago welcomes it as 29th member in move that has left its citizens divided The Guardian, 25 May 2017.

- МИД РФ: ответ НАТО на предложения российских военных неконкретный и размытый // ″Расширение НАТО″, TASS, 6 October 2016.

- Комментарий Департамента информации и печати МИД России в связи с голосованием в Скупщине Черногории по вопросу присоединения к НАТО Russian Foreign Ministry′s Statement, 28.04.17.

- Darmanović: Montenegro becomes EU member in 2022 20 April 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- "EU to map out membership for 6 western Balkan states", Michael Peel and Neil Buckley, Financial Times, 1 February 2018

- "Thousands march in Montenegro capital to demand president resign". Reuters. 16 March 2019.

- "Montenegrin Antigovernment Protests Enter Eighth Week". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 7 April 2019.

- Reuters (26 December 2019). "Serbs Protest in Montenegro Ahead of Vote on Religious Law". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "Montenegro's Attack on Church Property Will Create Lawless Society". Balkan Insight. 14 June 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- Masovna litija SPC u Podgorici (in Serbo-Croatian), retrieved 10 February 2020

- "Montenegro Adopts Law on Religious Rights Amid Protests by pro-Serbs". Voice of America. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "Montenegro's parliament approves religion law despite protests". BBC. 27 December 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "Настављене литије широм Црне Горе". Politika Online. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- Press, The Associated (1 January 2020). "Several Thousand Protest Church Bill in Montenegro". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "Thousands at protest headed by Bishop Amfilohije in Montenegrin capital". N1 Srbija (in Serbian). Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "'Thousands will regret Vucic's absence in Montenegro'". N1 Srbija (in Serbian). Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "First kilometer deep cave explored by Czech team | ZO 6-14 Suchy Zleb". Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- Environment Reporter 2010. Environmental Protection Agency of Montenegro. 2011. p. 22.

- "Ustav Crne Gore" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- Ustavno uređenje, .me

- "Nation in Transit 2020: Dropping the Democratic Facade" (PDF). Freedom House. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "Foreign Policy". mvpei.gov.me. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013.

- Julian E. Barnes (25 May 2017). "Montenegro to Join NATO on June 5 – WSJ". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- "President Vujanovic's Closing Speech at the Crans Montana Forum". Predsjednik.me. 21 February 2006. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- "Adriatic Charter". Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- "NATO Formally Invites Montenegro as 29th Member". Associated Press. 19 May 2016. Archived from the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- Milic, Predrag (5 June 2017). "Defying Russia, Montenegro finally joins NATO". ABC News. Archived from the original on 7 June 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- "Spremaju se za Avganistan". Vijesti.me. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- "Popis stanovništva, domaćinstava i stanova u Crnoj Gori 2011. godine" [Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Montenegro 2011] (PDF) (Press release) (in Serbo-Croatian and English). Statistical office, Montenegro. 12 July 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- "GDP per capita in PPS". European Commission. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- "5. Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. April 2011.

- FDI falls across West Balkans, except Montenegro. Reuters India 10 December 2009. Retrieved 14 December 2009.

- "Montenegro's leader sees slow economic recovery". balkans.com. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011.

- "Montenegro at a glance" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2011.

- Milosevic, Milena. "EU Farming Standards Pose Test For Montenegro". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- Mark Hillsdon (27 February 2017). "The European capital you'd never thought to visit (but really should)". The Daily Telegraph.

- "50 Places of a Lifetime". National Geographic. 17 September 2009. Archived from the original on 29 March 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- "The 31 Places to Go in 2010". The New York Times. 7 January 2010. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- "10 Top Hot Spots of 2009 by Yahoo Travel". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on 5 November 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- Leue, Holger. "Where to go in June". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 5 June 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- "America Sending their Best Adventure Racers to Montenegro". Adventureworldmagazineonline.com. 4 June 2010. Archived from the original on 10 July 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- "Popis stanovništva, domaćinstava i stanova u Crnoj Gori 2011. godine" [Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Montenegro 2011] (PDF) (Press release) (in Serbo-Croatian and English). Statistical office, Montenegro. 12 July 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- "Montenegro, country report" (PDF). European Commission. December 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 August 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- Montenegro: A Modern History. I.B. Tauris. 2009. ISBN 9781845117108.

- "Montenegrin Census' from 1909 to 2003". Njegos.org. 23 September 2004. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- "Romani, Balkan in Montenegro". Joshua Project. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Montenegro: The money came and went – and Romani families are still unhoused". Romea.cz. 18 July 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- Archived 2 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine Vijesti: The majority of youth below 18 years of age speaks the Montenegrin language (26 July 2011)

- Matica crnogorska: Third deep research of public opinion regarding the identity attitudes of the citizens of Montenegro (2013)

- "Pilgrims Flock to Ostrog, Montenegro's Healing Shrine". Balkan Insight. 12 May 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Pettifer, James (2007). Strengthening Religious Tolerance for a Secure Civil Society in Albania and the Southern Balkans. IOS Press. ISBN 978-1-58603-779-6.

- Larkin, Barbara (2001). International Religious Freedom 2000: Annual Report: Submitted by the U.S. Department Of State. Diane Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7567-1229-7.

- Rifat Fejzic, the reis (president) of the Islamic community in Montenegro Archived 21 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine Today's Zaman

- Ivan Jovović, 2013, Dvooltarske crkve na crnogorskom primorju {Dio istoričara u tumačenju ovog procesa svjesno izostavlja notornu činjenicu da je katolicizam na crnogorskom prostoru autohton još od vremena dinastije Vojislavljevića, "Part of historians in interpreting this process, consciously omits the obvious fact that Catholicism in Montenegrin territory has been indigenous since the time of the Vojislavljevic dynasty", https://www.maticacrnogorska.me/files/53/06%20ivan%20jovovic.pdf #page=67

- Šestović, Aleksandar. "Kotor". Kotoronline.com. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- "Чојство и јнаштво старих Црногораца, Цетиње 1968. 3–11". Web.f.bg.ac.rs. Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- "Oblikovanje crnogorske nacije u doba petrovica njegosa, "Cojstvo je osobeno svojstvo Crnogoraca, koje su uzdigli u najvecu vrlinu i uzor."".

Sources

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1991), The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century, University of Michigan Press, ISBN 978-0-472-08149-3

- John V.A. Fine. (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2007). Hitler's New Disorder: The Second World War in Yugoslavia. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-1-85065-895-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Banac, Ivo. The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics Cornell University Press, (1984) ISBN 0-8014-9493-1

- Fleming, Thomas. Montenegro: The Divided Land (2002) ISBN 0-9619364-9-5

- Longley, Norm. The Rough Guide to Montenegro (2009) ISBN 978-1-85828-771-3

- Morrison, Kenneth. Montenegro: A Modern History (2009) ISBN 978-1-84511-710-8

- Roberts, Elizabeth. Realm of the Black Mountain: A History of Montenegro (Cornell University Press, 2007) 521pp ISBN 978-1-85065-868-9

- Stevenson, Francis Seymour. A History of Montenegro 2002) ISBN 978-1-4212-5089-2

- Özcan, Uğur II. Abdulhamid Dönemi Osmanlı-Karadağ Siyasi İlişkileri [Political relations between the Ottoman Empire and Montenegro in the Abdul Hamid II era] (2013) Türk Tarih Kurumu Turkish Historical Society ISBN 978-975-16-2527-4

External links

- Official website of the Government of Montenegro (English)

- "Montenegro". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Montenegro from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Montenegro at Curlie

- Montenegro profile from the BBC News

- Culture Corner – leading Montenegrin web portal for culture

- Official Website National Parks Montenegro

.jpg)

_w_Cetinje_02.jpg)

.svg.png)