Withdrawal from the European Union

Withdrawal from the European Union is the legal and political process whereby an EU member state ceases to be a member of the Union. Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) states that "Any Member State may decide to withdraw from the Union in accordance with its own constitutional requirements".[1]

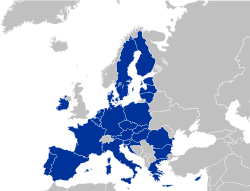

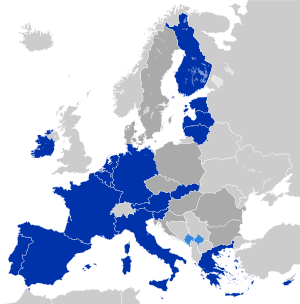

As of February 2020 the United Kingdom is the only former member state to formally undertake the process of withdrawing from the European Union. This began when the UK Government triggered Article 50 to begin the UK's withdrawal from the EU on 29 March 2017 following a June 2016 referendum, and the withdrawal was scheduled in law to occur on 29 March 2019.[2] Subsequently, the UK sought, and was granted, a number of Article 50 extensions until 31 January 2020. On 23 January 2020, the Withdrawal agreement was ratified by the Parliament of the United Kingdom, and on 29 January 2020 by the European Parliament. The UK left the EU on 31 January 2020 at 23:00 GMT ending 47 years of membership.[3][4]

Three territories of EU member states have withdrawn: French Algeria (in 1962, upon independence),[5] Greenland (in 1985, following a referendum)[6] and Saint Barthélemy (in 2012),[7] the latter two becoming Overseas Countries and Territories of the European Union.

Background

The states who were set to accede to the EU in 2004 pushed for an exit right during the 2002–2003 European Convention. The acceding states wanted the option to exit the EU in the event that EU membership would adversely affect them. During negotiations, eurosceptics in states such as the UK and Denmark subsequently pushed for the creation of Article 50.[8]

Article 50, which allows a member state to withdraw, was originally drafted by Scottish cross-bench peer and former diplomat Lord Kerr of Kinlochard, the secretary-general of the European Convention, which drafted the Constitutional Treaty for the European Union.[9] Following the failure of the ratification process for the European Constitution, the clause was incorporated into the Treaty of Lisbon which entered into force in 2009.[10]

Prior to this, no provision in the treaties or law of the EU outlined the ability of a state to voluntarily withdraw from the EU. The absence of such a provision made withdrawal technically difficult but not impossible.[11] Legally there were two interpretations of whether a state could leave. The first, that sovereign states have a right to withdraw from their international commitments;[12] and the second, the treaties are for an unlimited period, with no provision for withdrawal and calling for an "ever closer union" – such commitment to unification is incompatible with a unilateral withdrawal. The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties states where a party wants to withdraw unilaterally from a treaty that is silent on secession, there are only two cases where withdrawal is allowed: where all parties recognise an informal right to do so and where the situation has changed so drastically, that the obligations of a signatory have been radically transformed.[11]

Procedure

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union, enacted by the Treaty of Lisbon on 1 December 2009, introduced for the first time a procedure for a member state to withdraw voluntarily from the EU.[11] The article states that:[13]

- Any Member State may decide to withdraw from the Union in accordance with its own constitutional requirements.

- A Member State which decides to withdraw shall notify the European Council of its intention. In the light of the guidelines provided by the European Council, the Union shall negotiate and conclude an agreement with that State, setting out the arrangements for its withdrawal, taking account of the framework for its future relationship with the Union. That agreement shall be negotiated in accordance with Article 218(3)[14] of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. It shall be concluded on behalf of the Union by the Council [of the European Union], acting by a qualified majority, after obtaining the consent of the European Parliament.

- The Treaties shall cease to apply to the State in question from the date of entry into force of the withdrawal agreement or, failing that, two years after the notification referred to in paragraph 2, unless the European Council, in agreement with the Member State concerned, unanimously decides to extend this period.

- For the purposes of paragraphs 2 and 3, the member of the European Council or of the Council representing the withdrawing Member State shall not participate in the discussions of the European Council or Council or in decisions concerning it.

A qualified majority shall be defined in accordance with Article 238(3)(b) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

- If a State which has withdrawn from the Union asks to rejoin, its request shall be subject to the procedure referred to in Article 49.

This provision does not cover certain overseas territories which under TFEU Article 355 do not require a full treaty revision.[15]

Invocation

Thus, once a member state has notified the European Council of its intention to leave, a period begins during which a withdrawal agreement is negotiated, setting out the arrangements for the withdrawal and outlining the country's future relationship with the Union. Commencing the process is up to the member state that intends to leave.

The article allows for a negotiated withdrawal, due to the complexities of leaving the EU. However, it does include in it a strong implication of a unilateral right to withdraw. This is through the fact that a state would decide to withdraw "in accordance with its own constitutional requirements" and that the end of the treaties' application in a member state that intends to withdraw is not dependent on any agreement being reached (it would occur after two years regardless).[11]

Negotiation

The treaties cease to apply to the member state concerned on the entry into force of the withdrawal agreement or, in the absence of such an agreement, two years after the member state notified the European Council of its intention to leave, although this period can be extended by unanimous agreement of the European Council.[16]

The leaving agreement is negotiated on behalf of the EU by the European Commission on the basis of a mandate given by the remaining Member States, meeting in the Council of the European Union. It must set out the arrangements for withdrawal, taking account of the framework for the member state's future relationship with the EU, though without itself settling that framework. The agreement is to be approved on the EU side by the Council of the EU, acting by qualified majority, after obtaining the consent of the European Parliament. For the agreement to pass the Council of the EU it needs to be approved by at least 72 percent of the continuing member states representing at least 65 percent of their population.[17]

The agreement is concluded on behalf of the Union by the Council and must set out the arrangements for withdrawal, including a framework for the State's future relationship with the Union, negotiated in accordance with Article 218(3) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. The agreement is to be approved by the Council, acting by qualified majority, after obtaining the consent of the European Parliament. Should a former Member State seek to rejoin the European Union, it would be subject to the same conditions as any other applicant country.[18]

Remaining members of the EU would need to manage consequential changes over the EU's budgets, voting allocations and policies brought about by the withdrawal of any member state.[19]

Failure of negotiations

This system provides for a negotiated withdrawal, rather than an abrupt exit from the Union. This preference for a negotiated withdrawal is based on the expected complexities of leaving the EU (including concerning the euro) when so much European law is codified in member states' laws. However, the process of Article 50 also includes a strong implication of unilateral right to withdraw. This is through the fact the state would decide "in accordance with its own constitutional requirements" and that the end of the treaties' application in said state is not dependent on any agreement being reached (it would occur after two years regardless).[11] In other words, the European Union can not block a member state from leaving.

If negotiations do not result in a ratified agreement, the seceding country leaves without an agreement, and the EU Treaties shall cease to apply to the seceding country, without any substitute or transitional arrangements being put in place. As regards trade, the parties would likely follow World Trade Organization rules on tariffs.[20]

Re-entry or unilateral revocation

Article 50 does not spell out whether Member States can rescind their notification of their intention to withdraw during the negotiation period while their country is still a Member of the European Union. However, the President of the European Council said to the European Parliament on 24 October 2017 that “deal, no deal or no Brexit” is up to Britain. Indeed, the prevailing legal opinion among EU law experts and the EU institutions themselves is that a member state intending to leave may change its mind, as an “intention” is not yet a deed and intentions can change before the deed is done.[21] Until the Scottish Government did so in late 2018, the issue had been untested in court. On 10 December 2018, the European Court of Justice ruled that it would be “inconsistent with the EU treaties’ purpose of creating an ever closer union among the peoples of Europe to force the withdrawal of a member state” against its wishes, and that consequently an Article 50 notification may be revoked unilaterally by the notifying member without the permission of the other EU members, provided the state has not already left the EU, and provided the revocation is decided “following a democratic process in accordance with national constitutional requirements”.[22][23][24]

The European Parliament resolution of 5 April 2017 (on negotiations with the United Kingdom following its notification that it intends to withdraw from the European Union) states, "a revocation of notification needs to be subject to conditions set by all EU-27,[lower-alpha 1] so that it cannot be used as a procedural device or abused in an attempt to improve on the current terms of the United Kingdom’s membership."[25] The European Union Policy Department for Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs has stated that a hypothetical right of revocation can only be examined and confirmed or infirmed by the EU institution competent to this purpose, namely the CJEU.[26] In addition the European Commission considers that Article 50 does not provide for the unilateral withdrawal of the notification.[27] Lord Kerr, the British author of Article 50, also considers the process is reversible[28] as does Jens Dammann.[29] Professor Stephen Weatherill disagrees.[30] Former Brexit Secretary David Davis has stated that the British Government "does not know for sure" whether Article 50 is revocable; the British prime minister [then Theresa May] "does not intend" to reverse it.[28]

Extension of the two years time from notification to exit from the union, still requires unanimous support from all member countries, that is clearly stated in Article 50(3).

Should a former member state seek to rejoin the European Union after having actually left, it would be subject to the same conditions as any other applicant country and need to negotiate a Treaty of Accession, ratified by every Member State.[31]

Outermost regions

TFEU Article 355(6), introduced by the Treaty of Lisbon allows the status of French, Dutch and Danish overseas territories to be changed more easily, by no longer requiring a full treaty revision. Instead, the European Council may, on the initiative of the member state concerned, change the status of an overseas country or territory (OCT) to an outermost region (OMR) or vice versa.[32]

Withdrawals

Some former territories of European Union members broke formal links with the EU when they gained independence from their ruling country or were transferred to an EU non-member state. Most of these territories were not classed as part of the EU, but were at most associated with OCT status, and EC laws were generally not in force in these countries.

Some current territories changed or are in the process of changing their status so that, instead of EU law applying fully or with limited exceptions, EU law mostly will not apply. The process also occurs in the opposite direction, as formal enlargements of the union occur. The procedure for implementing such changes was made easier by the Treaty of Lisbon.

Past withdrawals

Territories

Algeria

French Algeria had joined the European Communities as part of the French Republic (since legally it was not a colony of France, but rather one of its overseas departments). Upon independence in 1962, Algeria left France and thus left the European Communities.

Greenland

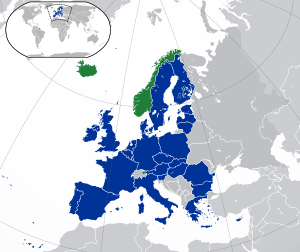

Greenland chose to leave the EU predecessor without also seceding from a member state. It initially voted against joining the EEC when Denmark joined in 1973, but because Denmark as a whole voted to join, Greenland, as a county of Denmark, joined too. When home rule for Greenland began in 1979, it held a new referendum and voted to leave the EEC. After wrangling over fishing rights, the territory left the EEC in 1985,[33] but remains subject to the EU treaties through association of Overseas Countries and Territories with the EU. This was permitted by the Greenland Treaty, a special treaty signed in 1984 to allow its withdrawal.[34]

Saint Barthélemy

Saint Martin and Saint-Barthélemy in 2007 seceded from Guadeloupe (overseas department of France and outermost region (OMR) of the EU) and became overseas collectivities of France, but at the same time remained OMRs of the European Union. Later, the elected representatives of the island of Saint-Barthélemy expressed a desire to "obtain a European status which would be better suited to its status under domestic law, particularly given its remoteness from the mainland, its small insular economy largely devoted to tourism and subject to difficulties in obtaining supplies which hamper the application of some European Union standards." France, reflecting this desire, requested at the European Council to change the status of Saint Barthélemy to an overseas country or territory (OCT) associated with the European Union.[35] The status change came into effect from 1 January 2012.[35]

Member states

United Kingdom

The UK formally left the EU on 31 January 2020, following on a public vote held in June 2016.[36] However, she benefits from a transition period to give time to negotiate a trade deal between the UK and the EU. The Brexit should lead to changes in 2021 at the end of this transition period, with or without a trade deal, in various topics.

The British government led by David Cameron held a referendum on the issue in 2016; a majority voted to leave the European Union. On 29 March 2017, arising from a decision by the Parliament of the United Kingdom, Prime Minister Theresa May invoked Article 50 in a letter to the President of the European Council, Donald Tusk. The UK was due to cease being a member at 00:00, 30 March 2019 Brussels time (UTC+1).[37] Following the UK Parliament's decisions not to ratify the Brexit withdrawal agreement negotiated between the European Council and the UK government, several extensions of the deadline were agreed.

Following a decisive election victory for Prime Minister Boris Johnson and the Conservative Party in December 2019, the UK Parliament ratified the European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020, approving the terms of withdrawal as formally agreed between the UK government and the EU Commission. After the European Parliament ratified the agreement on 29 January, the United Kingdom withdrew from the European Union at 23:00 London time (GMT) on 31 January 2020, with a withdrawal agreement in place.[38]

Advocates in other countries for withdrawal

Several states have political parties represented in national assemblies or the European Parliament that advocate withdrawal from the EU.[39]

As of June 2020, no country other than the United Kingdom has voted on whether to withdraw from the EU, political parties criticizing the federative trend of the European Union and advocating withdrawal have gained prominence in several member states since the European Parliament election in 2014, similarly to the rise of UKIP in the United Kingdom.

Denmark

The Netherlands

In The Netherlands, the main parties advocating for a withdrawal are the Forum for Democracy.[40]

Czechia

Greece

In Greece, the Golden Dawn[42][43] and Greek Solution is campaigning for a withdrawal.

Secession from a member state

There are no clear agreements, treaties or precedents covering the scenario of an existing EU member state breaking into two or more states. The question is whether one state is a successor rump state which remains a member of the EU and the other is a new state which must reapply and be accepted by all other member states to remain in the EU, or alternatively whether both states retain their EU membership following secession.[44][45]

In some cases, a region leaving its state would leave the EU - for example, if any of the various proposals for the enlargement of Switzerland from surrounding countries were to be implemented at a future date.

During the failed Scottish independence referendum of 2014, the European Commission said that any newly independent country would be considered as a new state which would have to negotiate with the EU to rejoin, though EU experts also suggested transitional arrangements and an expedited process could apply.[46][47][48] Political considerations are likely to have a significant influence on the process; in the case of Catalonia, for example, other EU member states may have an interest in blocking an independent Catalonia's EU membership in order to deter independence movements within their own borders.[49]

Legal effect on EU citizenship

Citizenship of the European Union is dependent on citizenship (nationality) of a member state, and citizenship remains a competence entirely vested with the member states. Citizenship of the EU can therefore only be acquired or lost by the acquisition or loss of citizenship of a member state. A probable but untested consequence of a country withdrawing from the EU is that, without otherwise negotiated and then legally implemented, its citizens are no longer citizens of the EU.[50] But the automatic loss of EU citizenship as a result of a member state withdrawing from the EU is the subject of debate.[51] In fact British citizens living in some EU member states have lost their quality of EU citizen.

Expulsion

While a state can leave, there is no provision for a state to be expelled. But TEU Article 7 provides for the suspension of certain rights of a member state if a member persistently breaches the EU's founding values.

See also

Footnotes

- In this context, EU-27 means the 27 European Union countries involved in Brexit negotiations with the UK; in other words, the EU (as of 2017) except for the United Kingdom. Historically, EU-27 was used as shorthand for the membership prior to the accession of Croatia.

References

- "Article 50". Eurostep. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- "Confirmation of UK Government agreement to Article 50 extension". GOV.UK.

- "MPs back Johnson's plan to leave EU on 31 January". 20 December 2019 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- "Brexit: European Parliament overwhelmingly backs terms of UK's exit". BBC News. 29 January 2020.

- Ziller, Jacques. "The European Union and the Territorial Scope of European Territories" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- "What is Greenland's relationship with the EU?". Folketing. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- Hay, Iain (2013). Geographies of the superrich. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 196. ISBN 9780857935694. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- Huysmans, Martijn (2019). "Enlargement and exit: The origins of Article 50". European Union Politics. 20 (2): 155–175. doi:10.1177/1465116519830202. hdl:1874/380979.

- "Article 50 was designed for European dictators, not the UK, says man who wrote it". The Independent. 29 March 2017.

Article 50 was designed to be used by a dictatorial regime, not the UK government, the man who wrote it has said. ... As Secretary General of the European Convention in the early 2000s, Lord Kerr played a key role in drafting a constitutional treaty for the EU that included laws on the process by which states can leave the bloc.

- "Article 50 author Lord Kerr says Brexit not inevitable". BBC News. 3 November 2016.

After leaving the foreign office, he was secretary-general of the European [C]onvention, which drafted what became the Lisbon treaty. It included Article 50 which sets out the process by which any member state can leave the EU.

- Athanassiou, Phoebus (December 2009). "Withdrawal and Expulsion from the EU and EMU: Some Reflections" (PDF). Legal Working Paper Series. European Central Bank (10): 9. ISSN 1830-2696. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- Hurd, Ian (2013). International Organizations: Politics, Law, Practice. Cambridge University Press. p. 10. ISBN 9781107040977.

- "Consolidated Version of the Treaty on European Union" (PDF). HM Government.

- "page 99 of 344".

- Instead, the European Council may, on the initiative of the member state concerned, change the status of an overseas country or territory (OCT) to an outermost region (OMR) or vice versa.

- Article 50(3) of the Treaty on European Union.

- Renwick, Alan (19 January 2016). "What happens if we vote for Brexit?". The Constitution Unit Blog. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- Article 50(4) of Lisbon Treaty which cites Article 49 Accession process

- Oliver, Tim. "Europe without Britain: Assessing the Impact on the European Union of a British Withdrawal". Stiftung Wissenshaft und Politik. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- "What will Brexit mean for British trade?". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- "We have not passed the point of no return – Richard Corbett". 26 April 2017.

- UK can cancel Brexit by unilaterally revoking Article 50, European Court of Justice rules, The Independent, 10 December 2018. "The court said any revocation must be decided “following a democratic process in accordance with national constitutional requirements”.

- Patrick Smyth (10 December 2018). "Brexit: UK can revoke Article 50, European court rules". The Irish Times. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

In Monday’s judgment, the full court has ruled that when a member state has notified the European Council of its intention to withdraw from the European Union, that member state is free to revoke unilaterally that notification. That possibility exists for as long as a withdrawal agreement concluded between the EU and that member state has not entered into force or, if no such agreement has been concluded, for as long as the two-year period from the date of the notification of the intention to withdraw from the EU, and any possible extension, has not expired.

- "Judgment in Case C-621/18 Press and Information Wightman and Others v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union(press release)" (PDF). Court of Justice of the European Union. 10 December 2018. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

The United Kingdom is free to revoke unilaterally the notification of its intention to withdraw from the EU

- "European Parliament resolution of 5 April 2017 on negotiations with the United Kingdom following its notification that it intends to withdraw from the European Union, paragraph L". European Parliament. 5 April 2017.

- "The (ir-)revocability of the withdrawal notification under Article 50 TEU – Conclusions" (PDF). The European Union Policy Department for Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs. March 2018.

- "State of play of Article 50 negotiations with the United Kingdom". The European Commission. 12 July 2017.

- "Chief EU negotiator pushing to ensure Britain can't pull back from two-year Brexit process". 8 April 2017.

- Dammann, Jens (Spring 2017). "Revoking Brexit: Can member states rescind their declaration of withdrawal from the European Union?". Columbia Journal of European Law. Columbia Law School. 23 (2): 265–304. SSRN 2947276. Retrieved 5 April 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Preview.

- "EU Law Analysis - Expert insight into EU law developments - Can an Article 50 notice of withdrawal from the EU be unilaterally revoked?". University of Essex. 16 January 2018.

- Article 50(4) of Lisbon Treaty, which cites Article 49 accession process.

- The provision reads:

"6. The European Council may, on the initiative of the Member State concerned, adopt a decision amending the status, with regard to the Union, of a Danish, French or Netherlands country or territory referred to in paragraphs 1 and 2. The European Council shall act unanimously after consulting the Commission."

— Treaty of Lisbon Article 2, point 293 - "Greenland Out of E.E.C.," New York Times (4 February 1985)

- "European law mentioning Greenland Treaty".

- "Draft European Council Decision on amendment of the European status of the island of Saint-Barthélemy – adoption" (PDF).

- Hunt, Alex; Wheeler, Brian (3 November 2016). "Brexit: All you need to know about the UK leaving the EU". BBC News.

- "House of Commons Briefing Paper 7960, summary". House of Commons. 6 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- "Advice for British nationals travelling and living in Europe". British Government Website. The U.K. Government. 19 January 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- "Brussels' Fear of the True Finns: Rise of Populist Parties Pushes Europe to the Right," Spiegel (25 April 2011).

- "PVV: Nederland moet uit EU. (The Netherlands should get out of the EU)". Nos.nl. 3 July 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- "EU could crumble to NOTHING as Italexit serious threat says George Soros -'tragic reality'". express.co.uk. 22 May 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- Πολιτικές Θέσεις (in Greek). Golden Dawn. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- "In crisis-ridden Europe, euroscepticism is the new cultural trend". 10 October 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- Edward, David, "Scotland's Position in the European Union", Scottish Parliamentary Review, Vol. I, No. 2 (Jan 2014) [Edinburgh: Blacket Avenue Press]

- "Scottish independence: Irish minister says EU application 'would take time'". BBC. 25 January 2013. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- Carrell, Jennifer Rankin Severin (14 March 2017). "Independent Scotland 'would have to apply to join EU' – Brussels official". The Guardian – via www.theguardian.com.

- "An independent Scotland could be 'fast-tracked into the EU'". The Scotsman. 20 February 2017. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- "Reality Check: Could Scotland inherit the UK's EU membership?". BBC News. 24 June 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- The Catalan independence movement is pro-EU – but will the EU accept it?, London School of Economics 10/OCT/17

- "Guidelines Involuntary Loss of European Citizenship (ILEC Guidelines 2015)" (PDF). ILEC Project.

- Rieder, Clemens M. (2013). "The Withdrawal Clause of the Lisbon Treaty in the Light of EU Citizenship (Between Disintegration and Integration)". Fordham International Law Journal. 37 (1): 147–174.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brexit. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Official EU Consolidated treaties – Charter of Fundamental Rights

- The Guardian (UK) – Article 50 special report

- Withdrawal and expulsion from the EU and EMU – some reflections

- Adrian Williamson, The case for Brexit: lessons from the 1960s and 1970s, History and Policy (2015)

- Draft Withdrawal Document - TF50 (2018) 55 – Commission to EU27 - 14 Nov 2018 (with United Kingdom)