Prince-Bishopric of Montenegro

The Prince-Bishopric of Montenegro (Митрополство Црногорско / Mitropolstvo Crnogorsko), located around modern-day Montenegro, was an ecclesiastical principality that existed from 1516 until 1852. It emerged from the bishops of Cetinje, later metropolitans, who defied Ottoman overlordship and transformed the parish of Cetinje to a de facto theocracy, ruling as Metropolitans (vladika, also rendered "Prince-bishop"). The history starts with Vavila, and the system was transformed into a hereditary one by Danilo Šćepčević, a bishop of Cetinje who united the several tribes of Montenegro into fighting the Ottoman Empire that had occupied most of southeastern Europe. Danilo was the first of the House of Petrović-Njegoš to occupy the office as Metropolitan of Cetinje until 1851, when Montenegro became a secular state (principality) under Danilo I Petrović-Njegoš. It also became a brief monarchy when it was temporary abolished 1767–1773, during which impostor Little Stephen posed as Russian Emperor and crowned himself Lord of Montenegro.

Prince-Bishopric of Montenegro Митрополство Црногорско Mitropolstvo Crnogorsko | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1516–1852 | |||||||||

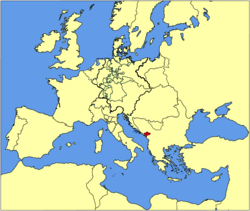

Location of Montenegro in Europe, 19th century | |||||||||

| Capital | Cetinje | ||||||||

| Common languages | Serbian | ||||||||

| Religion | Eastern Orthodox | ||||||||

| Government | Ecclesiastical principality (1516–1767, 1773–1852) | ||||||||

| Prince-bishop | |||||||||

• 1516–1520 | Vavila (first) | ||||||||

• 1851–1852 | Danilo II (last) | ||||||||

| Legislature | Assembly of Montenegro and the Highlands | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Establishment | 1516 | ||||||||

| 13 March 1852 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1851 | 5,475 km2 (2,114 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Currency | Montenegrin perun (proposed) | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | ME | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

Name

The state was virtually the Metropolitanate of Zeta under the supervision of the Petrović-Njegoš family. The name mostly used in historiography is "Metropolitanate of Cetinje" or "Cetinje Metropolitanate" (Цетињска митрополија).[1] The highest office-holder of the polity was the Metropolitan (vladika, also rendered "prince-bishop").[2] Metropolitan Danilo I (1696–1735) called himself "Danil, Metropolitan of Cetinje, Njegoš, Duke of the Serb land" („Данил, владика цетињски, Његош, војеводич српској земљи...").[3][4] When Bjelopavlići and the rest of the Hills was joined into the state during the rule of Peter I, it was officially called "Black Mountain (Montenegro) and the Hills" (Црна Гора и Брда).[5]

Travers Twiss used the English term "Prince-Bishopric of Montenegro", for the first time, in 1861.[6]

History

The period of elective vladikas

Vladikas were elected for 180 years by clan chieftains and people on Montenegrin assembly called Zbor, an arrangement that was ultimately abandoned in favor of the hereditary system. The very first of them, Vavila, had a relatively peaceful reign without many Ottoman incursions, devoting most of his time to maintenance of printing press on Obod. His successor, German II, was not so fortunate. Skenderbeg Crnojević, an islamized member of Crnojević family put forth his claim on Montenegro, and sought to capture it as an Ottoman vassal. Vukotić, the civil governor of Montenegro, repulsed him, and such was the zeal of the Montenegrins for the Christian cause, that they marched into Bosnia and raised the siege of Jajce, where the Hungarian garrison was closely hemmed in by Ottoman troops.[7] The Turks were too much occupied with the Hungarian war to take revenge, and it was not till 1570 that Montenegro had to face another Ottoman invasion. The next three vladikas, Paul, Nicodin, and Makarios, availed themselves of this long period of repose to increase the publications of the press, and numerous psalters and translations of the Gospels were produced in this small and remote Principality.[7]

In 1570, large-scale invasions were renewed. Montenegro faced two of them led by Ali-pasha of Shkodër, the first of which was repulsed, but the later took a heavy toll on its inhabitants. Pahomije, the prince-bishop at that moment, was unable to reach Ipek for the ceremony of consecration, and his authority was therefore weakened in the eyes of his people. The islamized renegades, allowed to settle in the country at the time of Staniša's defeat, welcomed the Pasha's army with open arms, allowing him to seize the castle of Obod and destroy the precious printing-press, which Ivan Crnojević had established there a century earlier.[7] During Pahomije's rule, Montenegrins fought in War of Cyprus on behalf of Republic of Venice.[8]

The next vladika, Rufim Njeguš, ruled from 1594 to 1631. He was noted as an exceptional military leader, aiding the Banat Uprising (1594) and defeating several Ottoman invasions of Montenegro - in 1604, 1612, and 1613.

The first of them culminated in the Battle of Lješkopolje (1604). Sanjak-bey of Shkodër Ali-bey Mimibegović led an army of 12,000 from Podgorica and clashed with 400 Montenegrins in Lješanska nahija. Rufim reinforced them with 500 Katunjani during the day and sent dozens of small three-members groups, in total amount of 50 warriors to spy and to attack the opponent from rear. The battle lasted through whole night, when at the dawn Montenegrins launched a sudden charge surprising the enemy. Ali-beg was wounded and retreated with 3,500 casualties, while his second-in-command Šaban Ćehaja was killed.[8][9]

Eight years later, in 1612, the Sultan determined that he would sweep the defiant mountaineers off the face of the earth. An army of 25.000 men was despatched against the principality, The decisive battle took place not far from Podgorica. But the Turkish cavalry was useless in such a country. The small band of Montenegrins held their ground, the enemy threw himself against their rocks in vain, and the flower of the Ottoman cavalry was left dead on the field.[7]

Next year a still larger force of was collected by newly appointed Sanjak-bey of Shkodër Arslan-bey Balićević to attack Montenegro.[7] Bey split his forces in two, and tasked first army with penetration of Cetinje and second army with suppressing rebellious forces around Spuž. Both armies failed, as the first one was stopped in Lješkopolje again without reaching Cetinje, and the second one was defeated when Rufim personally led a side attack of 700 Katunjani to the aid of Piperi, Bjelopavlići and Rovčani forces which were already engaging enemy around the village of Kosov lug. Six months were occupied in skirmishes and ambuscades, and it was not till 10 September 1613, that the two armies met on the spot where Staniša had been defeated more than a century before. The Montenegrins, although assisted by some neighbouring tribes, were completely outnumbered. Despite this, the Montenegrins decisively defeated the Turkish forces. Arslan-bey was wounded, and the heads of his second-in-command and a hundred other Turkish officers were carried off and stuck on the ramparts of Cetinje. The Ottoman troops fled in disorder; many were drowned in the waters of the Morača, many more were killed by their pursuers.[7][8]

In 1623 Soliman, Pasha of Shkodër, with 80.000 men, marched into the country with the intention of finally annexing it. For twenty days the opposing forces were engaged in almost ceaseless conflicts. But the invaders at last reached Cetinje. The capital was taken, and the monastery of Ivan Crnojević sacked. A tribute was imposed upon those who submitted, while the resistance retired to the inaccessible heights of the Lovćen, and descended upon the Turkish camp. The Pasha realized that the bare rocks afforded no subsistence to his host; so, leaving a small army of occupation behind, he returned to the fertile plains of Albania. At once the Montenegrins attacked the Turkish garrisons, while the warlike tribes of the Kuči and Klimenti on the Albanian border fell upon the main body which was returning to Shkodër, near Podgorica, and almost annihilated it. Montenegro was once more free.[7]

During rule of Mardarije I, Visarion I, and Mardarije II, Montenegrins actively fought in War of Candia (1645-1669) on the side of Venetians, while during rules of last four elective vladikas and the first hereditary one, they took part in Morean War (1684-1699).[8] One of the most notable battles of that war in which Montenegro took part was the Battle of Herceg Novi in 1687, in which Venetians besieged the city from seaside, with Montenegrins doing the same from the land side.[10] The total amount of Montenegrins which have fell was 1500, while only 170 Venetians were slain in battle.[11] Montenegrins played a pivotal role in intercepting forces of Topal Pasha which were sent to lift the siege. A force of 300[12] Montenegrins ambushed the army of Topal Pasha, which numbered as much as 20.000 according to The Mountain Wreath,[13] on the narrow pass in Kameno field and routed it.

Danilo

During the reign of Danilo two important changes occurred in the wider European context of Montenegro: the expansion of the Ottoman state was gradually reversed, and Montenegro found in the Russian Empire a powerful new patron to replace the declining Venice. The replacement of Venice by Russia was especially significant, since it brought financial aid (after Danilo visited Peter the Great in 1715), modest territorial gain, and, in 1789, formal recognition by the Ottoman Porte of Montenegro's independence as a state under Petar I Petrović Njegoš.

Sava and Vasilije

Metropolitan Danilo was succeeded by Metropolitan Sava and Metropolitan Vasilije. Sava was predominantly occupied with clerical duties and did not enjoy as much charisma among tribal heads as his predecessor did. However, he managed to keep good relations with Russia, and to get considerable help from Peter the Great's successor empress Elizabeth. During his trip to Russia his deputy Vasilije Petrović gained considerable respect among the tribes by giving support to those who at that time were attacked by the Ottomans. He was as much hated by the Venetians as he was by the Ottomans. Vasilije was also active in trying to solicit Russian support for Montenegro. For that purpose he traveled to Russia three times, where he also died in 1766. He also wrote one of the earliest historical books on Montenegro, History of Montenegro.

Šćepan Mali

In 1766, a person known as Šćepan Mali ("Stephen the Little") appeared in Montenegro, rumoured to be Russian Emperor Peter III, who in fact had been assassinated in 1762. Having affection for Russia, the Montenegrins accepted him as their Emperor (1768). Metropolitan Sava had told the people that Šćepan was an ordinary crook, but the people believed him instead. Following this event Šćepan put Sava under house arrest in the Stanjevići monastery. Šćepan was very cruel and thus both respected and feared. After realizing how much respect he commanded, and that only he could keep Montenegrins together, Russian diplomat Dolgoruki abandoned his efforts to discredit Šćepan, even giving him financial support. In 1771 Šćepan founded the permanent court composed of the most respected clan chiefs, and stubbornly insisted on respect of the court's decision.

The importance of Šćepan's personality in uniting Montenegrins was realized soon after his assassination conducted by order of Kara Mahmud Bushati, the pasha of Scutari. Montenegrin tribes once again engaged into blood feuding among themselves. Bushati tried to seize the opportunity and attacked Kuči with 30,000 troops. For the first time since Metropolitan Danilo, the Kuči were helped by Piperi and Bjelopavlići, and defeated the Ottomans twice in two years.[14]

Petar I

After Šćepan's death, gubernadur (title created by Metropolitan Danilo to appease Venetians) Jovan Radonjić, with Venetian and Austrian help, tried to impose himself as the new ruler. However, after the death of Sava (1781), the Montenegrin chiefs chose archimandrite Petar Petrović, who was a nephew of Metropolitan Vasilije, as successor.

Petar I assumed the leadership of Montenegro at a very young age and during most difficult times. He ruled almost half a century, from 1782 to 1830. Petar I won many crucial victories against the Ottomans, including at Martinići and Krusi in 1796. With these victories, Petar I liberated and consolidated control over the Highlands (Brda) that had been the focus of constant warfare, and also strengthened bonds with the Bay of Kotor, and consequently the aim to expand into the southern Adriatic coast.

In 1806, as French Emperor Napoleon advanced toward the Bay of Kotor, Montenegro, aided by several Russian battalions and a fleet of Dmitry Senyavin, went to war against the invading French forces. Undefeated in Europe, Napoleon's army was however forced to withdraw after defeats at Cavtat and at Herceg-Novi. In 1807, the Russian–French treaty ceded the Bay to France. The peace lasted less than seven years; in 1813, the Montenegrin army, with ammunition support from Russia and Britain, liberated the Bay from the French. An assembly held in Dobrota resolved to unite the Bay of Kotor with Montenegro. But at the Congress of Vienna, with Russian consent, the Bay was instead granted to Austria. In 1820, to the north of Montenegro, the Morača tribe won a major battle against an Ottoman force from Bosnia.

During his long rule, Petar strengthened the state by uniting the often quarreling tribes, consolidating his control over Montenegrin lands, and introducing the first laws in Montenegro. He had unquestioned moral authority strengthened by his military successes. His rule prepared Montenegro for the subsequent introduction of modern institutions of the state: taxes, schools and larger commercial enterprises. When he died, he was by popular sentiment proclaimed a saint.

Petar II

Following the death of Petar I, his 17-year-old nephew, Rade Petrović became Metropolitan Petar II. By historian and literary consensus, Petar II, commonly called "Njegoš", was the most impressive of the prince-bishops, having laid the foundation of the modern Montenegrin state and the subsequent Kingdom of Montenegro. He was also the most acclaimed Montenegrin poet.

A long rivalry had existed between the Montenegrin metropolitans from the Petrović family and the Radonjić family, a leading clan which had long vied for power against the Petrović's authority. This rivalry culminated in Petar II's era, though he came out victorious from this challenge and strengthened his grip on power by expelling many members of the Radonjić family from Montenegro.

In domestic affairs, Petar II was a reformer. He introduced the first taxes in 1833 against stiff opposition from many Montenegrins whose strong sense of individual and tribal freedom was fundamentally in conflict with the notion of mandatory payments to the central authority. He created a formal central government consisting of three bodies, the Senate, the Guardia and the Perjaniks. The Senate consisted of 12 representatives from the most influential Montenegrin families and performed executive and judicial as well as legislative functions of government. The 32-member Guardia traveled through the country as agents of the Senate, adjudicating disputes and otherwise administering law and order. The Perjaniks were a police force, reporting both to the Senate and directly to the Metropolitan.

Before his death in 1851, Petar II named his nephew Danilo as his successor. He assigned him a tutor and sent him to Vienna, from where he continued his education in Russia. According to some historians Petar II most likely prepared Danilo to be a secular leader. However, when Petar II died, the Senate, under influence of Djordjije Petrović (the wealthiest Montenegrin at the time), proclaimed Petar II's elder brother Pero as Prince and not Metropolitan. Nevertheless, in a brief struggle for power, Pero, who commanded the support of the Senate, lost to the much younger Danilo who had more support among the people. In 1852, Danilo proclaimed a secular Principality of Montenegro with himself as Prince and formally abolished ecclesiastical rule.[15]

Aftermath

In Danilo I's Code, dated to 1855, he explicitly states that he is the "knjaz (duke, prince) and gospodar (lord) of the Free Black Mountain (Montenegro) and the Hills".[16]

The new Principality of Montenegro lasted until 1910, when Prince Nicholas I proclaimed the Kingdom of Montenegro.

Organization

- Common council (zbor) in Cetinje; assemblies of the Metropolitan and tribes that recognized his spiritual leadership.

- Aristocratic titles

- serdar (from Turkish serdar), tribal chieftain and general

- guvernadur (from Italian governatore), hereditary title appointed from the Radonjić brotherhood (1718–1831)

List of rulers

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Montenegro |

|

| Prehistory |

| Middle Ages and early modern |

|

| Modern and contemporary |

|

- Elective vladikas

- Vavila (Metropolitan from 1493) (1516–1520)

- German II (1520–1530)

- Pavle (1530–1532)

- Vasilije I (1532–1540)

- Nikodim (1540)

- Romi (1540–1559)

- Makarije (1560–1561)

- Ruvim I (1561–1569)

- Pahomije II (1569–1579)

- Gerasim (1575–1582)

- Venijamin (1582–1591)

- Nikanor and Stefan (1591–1593)

- Ruvim II (1593–1636)

- Mardarije I (1639–1649)

- Visarion I (1649–1659)

- Mardarije II (1659–1673)

- Ruvim III (1673–1685)

- Vasilije II (1685)

- Visarion II (1685–1692)

- Sava I (1694 – July 1696)

- Petrović-Njegoš Metropolitans of Cetinje

- Danilo I (1696–1735); by himself (1696–1719) and with Sava II (1719–1735)

- Sava II (1735–1782); by himself (1735–1750) and with Vasilije III (1750–1766)

- Prince

- Šćepan Mali (1767–1773)

- Metropolitan of Cetinje (not Petrović-Njegoš)

- Arsenije Plamenac (1781–1784)

- Petrović-Njegoš Metropolitans of Cetinje

References

- Milija Stanišić (2005). Dubinski slojevi trinaestojulskog ustanka u Crnoj Gori. Istorijski institut Crne Gore. p. 114.

Као што смо претходно казали, стицајем историјских и друштвених околности Цетињска митрополија је постала не само духовни него и политички центар Црне Горе, Брда и негдашњег Зетског приморја. Заједно са главарским ...

- Srdja Pavlovic (2008). Balkan Anschluss: The Annexation of Montenegro and the Creation of the Common South Slavic State. Purdue University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-55753-465-1.

- Matica srpska, Lingvistička sekcija (1974). Zbornik za filologiju i lingvistiku, Volume 17, Issues 1-2. Novi Sad: Matica srpska. p. 84.

Данил, митрополит Скендерије u Приморја (1715. г.),28 Данил, владика цетински Његош, војеводич српској земљи (1732. г.).

- Velibor V. Džomić (2006). Pravoslavlje u Crnoj Gori. Svetigora.

То се види не само по његовом познатом потпису „Данил Владика Цетињски Његош, војеводич Српској земљи" (Запис 1732. г.) него и из цјелокупког његовог дјелања као митрополита и господара. Занимљиво је у том контексту да ...

- Etnografski institut (Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti) (1952). Posebna izdanja, Volumes 4-8. Naučno delo. p. 101.

Када, за владе Петра I, црногорсксу држави приступе Б^елопавлиЬи, па после и остала Брда, онда je, званично, „Црна Гора и Брда"

- Travers Twiss (1861). The law of nations considered as independent political Communities. University Press. pp. 95–.

- Miller, William (1896). The Story of the Nations: The Balkans. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- "Momir M. Marković: Crnogorski rat". Forum.cdm.me. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- "Vladimir Corovic: Istorija srpskog naroda". Rastko.rs. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- Rotković, Radoslav (26 January 2006). "Bitka za Herceg Novi 1687". Republika. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- Jovanović, Jagoš (1998). Istorija Crne Gore, treće ispravljeno i dopunjeno izdanje. Podgorica. p. 83.

- Rotković, Radoslav (26 January 2006). "Bitka za Herceg Novi 1687". Republika. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- Petrović Njegoš, Petar II (1847). Gorski Vijenac.

- Jovanovic, Jagos (1947). Stvaranje Crnogorske drzave i razvoj Crnogorske nacionalnosti. Cetinje: Obod.

- Jovanovic 1947, p. 233

- Stvaranje, 7–12. Obod. 1984. p. 1422.

Црне Горе и Брда историјска стварност коЈа се не може занема- рити, што се види из назива Законика Данила I, донесеног 1855. године који гласи: „ЗАКОНИК ДАНИЛА I КЊАЗА И ГОСПОДАРА СЛОБОДНЕ ЦРНЕ ГОРЕ И БРДА".

Sources

- Stamatović, Aleksandar (1999). "Митрополија црногорска за вријеме митрополита Петровића". Кратка историја Митрополије Црногорско-приморске (1219-1999).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stanojević, Gligor; Vasić, Milan (1975). Istorija Crne Gore (3): od početka XVI do kraja XVIII vijeka. Titograd: Redakcija za istoriju Crne Gore. OCLC 799489791.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Popović, P.I. (1951) Crna Gora u doba Petra I i Petra II. Beograd: Srpska književna zadruga / SKZ

- Stanojević, G. (1962) Crna gora pred stvaranje države. Beograd

External links

.png)